The biosorption on fungal pellets is getting attention as an attractive water remediation technique, as it offers an enhanced biomass separation and a high resilience in severe environmental conditions. In this entry, biosorption capacity of fungal pellets towards heavy metals was reviewed. Available data about the adsorption capacity of pellets, their removal efficiency, and the operational conditions used were collected and synthesized. It was found that the biosorption of complex mixtures of pollutants on fungal pellets is scarcely studied, as well as the interfering effect of anions commonly found in water and wastewater. Furthermore, there is a lack of research with real wastewater and at pilot and large scale. These topics need to be further explored to take full advantage of fungal pellets on improving the quality of aquatic systems.

- Water pollution

- Biosorption

- Fungal biotechnology

- Fungal granules

- Water treatment

- Adsorption

- Metal removal

1. Fungal Pellets as Environmental Biotechnology Tools

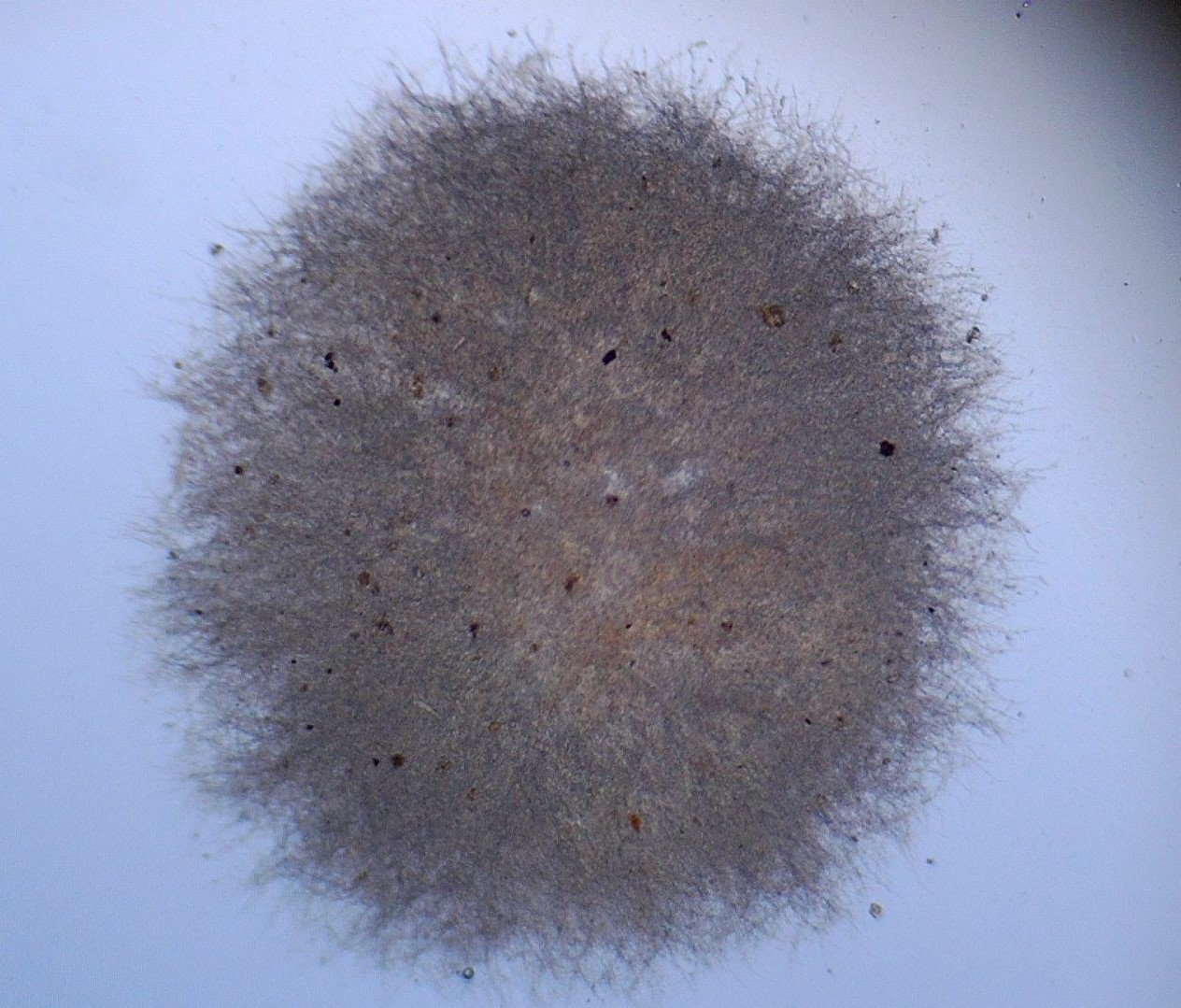

Fungi constitute a group of both unicellular and multicellular organisms with outstanding industrial and environmental applications. Multicellular fungi display development mechanisms quite different from those shown by plants and animals; these mechanisms are characterized by the formation of filament assemblies called hyphae, which grow only apically [1]. In liquid media, filamentous fungi grow as disperse mycelium or form granules visible as microspheres, known as fungal pellets. These pellets are spherical or ellipsoidal masses of entangled hyphae with a size varying from some hundreds of micrometers to several millimeters. Usually, these pellets have a nucleus of highly compacted hyphae; it is surrounded by a more dispersed ring zone, the “hairy region”, which comprises the zone where radial hyphal growth is occurring (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aspergillus tabacinus pellet.

Considerable research has been conducted recently to explore the potential of fungal pellets in industrial processes, as well as the factors influencing the granulation mechanism [2][3]. These pellets present several advantages over disperse mycelia, such as lower viscosity of the culture medium and easier biomass separation [3]. Besides, fungal pellets have proved to be resilient towards severe conditions, such as acidic media, fluctuating inputs of toxicants or low concentrations of nutrients [4], which is advantageous in environmental processes dealing with industrial wastewater or acid mine drainage, for instance. Furthermore, fungal pellets are a well-suited source of enzymes useful for organic compounds degradation [3]. The co-culturing of filamentous fungi with microalgae to ease the cell harvest has also been explored as a promising way to enhance biofuel production [5].

Several factors have been reported to be crucial to culturing fungal pellets. Among them, pH, agitation, medium composition, inoculation mode, and additives are commonly mentioned [6]. However, fungal pellets can show some drawbacks, such as hindered internal transport of nutrients leads to the apparition of non-viable zones inside the granules [3].

2. Water Pollution by Heavy Metals

The mobilization of heavy metals through the extraction of minerals and their further processing has led to the broad dispersion of these pollutants [7]. Thus, large wastewater volumes are generated annually with varying levels of heavy metals; among them, Cd, Cr, Cu, As, Hg, and Pb can be highlighted due to their toxicity and ubiquity [8][9].

There are two main sources of heavy metals in wastewater effluents: natural and anthropogenic. The first includes soil erosion, volcanic activities, weathering of rocks and minerals [8], while the main anthropogenic sources are paints and pigments, plastic stabilizers, electroplating, incineration of cadmium-containing plastics, and phosphate fertilizers for Cd [10][11]; tanneries and steel industries for Cr [12]; pesticides and wood preservatives for Cu [12][13] and As [14]; release from Au-Ag mining and coal combustion, and medical waste for Hg [15][16]; industrial effluents, kitchen appliances, surgical instruments, steel alloys, automobile batteries [17], aerial emission from combustion of leaded petrol, battery manufacture, herbicides, and insecticides for Pb [10][14][15].

The presence of heavy metals in wastewater raises several environmental issues, because these are conservative pollutants to which the “biodegradability” term does not apply. In addition, they are mobile and toxic in aquatic ecosystems [7][8][9][10]. Other of the main concerns is their potential to accumulate in living organisms, and then to biomagnificate through the trophic chains (i.e., the organisms from the higher trophic levels are polluted with higher contents of heavy metals). In this way, human health is threatened if these pollutants are present at high concentrations in food and water [18][19]. Besides, heavy metals cause oxidative stress by means of the formation of free radicals [20]. Oxidative stress refers to the enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species that may overwhelm the antioxidant defenses of cells, resulting in their permanent damage or death [21][22].

In view of the above, it is imperative to remove the heavy metals from wastewater before their discharge to the aquatic environment. Chemical precipitation, oxidation or reduction, ionic exchange, electrochemical processes, reverse osmosis, and other membrane separation technologies are among the most used treatment methods [9][23][24][25]. These technologies present some drawbacks, such as their relatively high cost, in some cases derived from the constant inputs of chemical reagents or energy, or their inefficiency to treat diluted streams (with concentrations of metals below 100 mg·L−1) [26]. This has generated a considerable interest in biosorption, which has demonstrated its efficiency to remove heavy metals at low operating costs [27][27][28]. In particular, filamentous fungi biomass has the potential to do so [29][30]. Several types of fungal biomass are promising sources of biosorbents to remove heavy metals from aquatic streams. These sources must be available at reduced costs, be able to remove high amounts of metals and, if possible, to be regenerated and reused more than once. Such a source could arise from the waste of large-scale fungal bioprocesses, which includes the antibiotic industrial production.

3. Fungal Pellets as Biosorbents for Heavy Metals

Fungal filaments contain all the components of eukaryotic cells and are covered by an unique cell wall with prominent amounts of glycoproteins, chitin, and glycans. Functional groups allowing biosorption such as hydroxyl, amine, carboxyl, among others, are profusely present in fungal cell walls .

It is worth mentioning that, unlike other pollutants, heavy metals can be removed from wastewater by a live biosorbent through different mechanisms such as: (i) chemical transformations involving phase changes (i.e., redox reactions or alkylation), (ii) bioaccumulation, which includes metabolism-dependent processes leading to the metal transport into the fungal cells, and (iii) biosorption, which is a surface mechanism that does not involve any metabolic process. The latter mechanism is considered to be the most significant in metals removal by fungal biomass, which can be attributed to ion exchange, coordination or covalent bonding to the cell wall [3]. On live fungal biomass, the sorption of heavy metals involves two stages: a fast metabolism-independent phase that relies on the available surface and it is of physicochemical nature, followed by a slow metabolism-dependent phase that implies the ion transport across the cell membrane [31][32]. From a quantitative point of view, the surface adsorption can represent the most part of the total ion removal, so that the union to the cell membranes could be the most significant mechanism of metal removal. This mechanism occurs in both alive and dead fungal biomass. In fact, dead cells can adsorb some metallic ions in a greater extent than live cells [32][33].

Rather than focusing separately on the fungal biosorption of each heavy metal reported in the bibliography, this section will review the main parameters involved in metal uptake by fungal biomass, which are the solution pH, the initial metal concentration, the biomass pretreatment, and the evaluation of the metal removal in multicomponent systems. Table 1 presents the adsorption capacities measured in several published studies, as well as the used experimental conditions.

Table 1. Biosorption of heavy metals by fungal pellets.

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Aspergillus carbonarius | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 200 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (L): 1 g (ww); time: 10 h |

100 | qexp: 1.7 | Not reported | [34] |

| Aspergillus flavus | Zn | pH: 5; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 34 °C; diameter of pellets: 1–3 mm; time: 6 days |

100 | Not reported | 40.9 ± 0.7% | [35] |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 59.7 ± 0.5% | |||||

| Aspergillus lentulus | Cu(II) 1 | pH: 5; amount of pellets (L): 1.27–4.86 g·L−1 (dw) |

75–800 | qexp: 12.1–124.5 | 19.8–78.4% | [36] |

| pH: 2–8; amount of pellets (L): 1.71–4.89 g·L−1 (dw) |

80 | qexp: 1.7–15.2 | 3.6–79.8% | |||

| Cr(III) 1 | Amount of pellets (L): 4.03–4.64 g·L−1 (dw) |

1000–5000 | qexp: 171.0–331.5 | 26.0–79.4% | ||

| Ni(II) 1 | pH: 2–8; amount of pellets (L): 1.37–4.55 g·L−1 (dw) |

70–210 | qexp: 5.2–11.1 | 6.7–42.1% | ||

| 70 | qexp: 1.2–8.6 | 3.7–41.4% | ||||

| Pb(II) 1 | Amount of pellets (L): 0.46–4.67 g·L−1 (dw) |

500–4000 | qexp: 76.1–1120 | 12.9–71.0% | ||

| Aspergillus niger | Cu(II) | pH: 5.3; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 1 g·L−1 (ww); time: 2 h |

30 | qmax: 8.1 | Not reported | [37] |

| Aspergillus niger 405 | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 200 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets: 1 g (ww); diameter of pellets: 1–3 mm; time: 10 h |

10 | qmax: 5.7 | Not reported | [38] |

| Zn(II) | qmax: 4.7 | |||||

| Ni(II) | qmax: 14.1 | |||||

| CrO42- | qmax: 7.2 | |||||

| Aspergillus japonicus | Fe(II) | pH: 2–10; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 1 g (ww) |

25–100 | qmax: 1.3 | Not reported | [39] |

| Ni(II) | qmax: 1.2 | |||||

| Cr(VI) | qmax: 1.9 | |||||

| Aspergillus japonicus | Hg(II) | qmax: 1.2 | Not reported | [39] | ||

| Industrial wastewater | pH: 2.1; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets: 2.25 g (ww) |

Ni(II): 44 Cr(VI): 90 |

Ni(II): qmax: 1.16 Cr(VI): qmax: 2.57 |

|||

| Funalia trogii | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 0.01 g·mL−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 3–5 mm; time: 30 min |

10–300 | qmax: 23.89 | 61% | [40] |

| Lentinus edodes | Hg(II) Cd(II) Zn(II) |

pH: 6; agitation: 400 rpm; T: 25 C, amount of pellets (L, A): 1 g·L−1 (ww); time: 2 h |

25–600 | (L): Hg(II) qmax: 358.1 Cd(II) qmax: 86.4 Zn(II) qmax: 37.7 |

Not reported | [41] |

| (A): Hg(II) qmax: 419.1 Cd(II) qmax: 299.4 Zn(II) qmax: 63.3 |

||||||

| Penicillium sp. | Sr(II) Th(IV) U(VI) |

pH: 5 for Sr(II) and U(VI); 3 for Th(IV); continuously stirred; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L, nFe3O4-pellets): 0.2 g·L−1; time: 48 h |

Sr(II): 1–30 Th(IV): 1–130 U(VI): 1–130 |

(L): Sr(II) qmax: 93.3 Th(II) qmax: 250.8 U(VI) qmax: 205.2 |

Sr (II), pH 8: 100% Th(IV), pH 5: 100% U(VI), pH 7: 100% |

[42] |

| Fe3O4-pellets: Sr(II) qmax: 109.9 Th(II) qmax: 280.8 U(VI) qmax: 223.9 |

||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum | Cs | pH: 5; air lift column system; liquid to solid ratio (v/v): 10:1; diameter of pellets: 5 mm; time: 3 h |

Cs: 13.3 | qmax: 119 | 50% | [43] |

| Sr | Sr: 8.8 | qmax: 92 | 39% | |||

| U | U: 23.8 | qmax: 147 | 62% | |||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | As(III) | pH: 4; agitation: 150 rpm; ambient room T; amount of pellets (L): 0.25–1.5 g·L−1 (ww); time: 24 h |

0.2–1 | qmax: 5.5 | Not reported | [44] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Zn | pH: 4.5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L, nSe0-pellets): 3.2 g·L−1 (ww); time: 24 h |

10–50 | (L): qmax: 1.9–8.3 | (L): 56.2 ± 2.8% | [45] |

| (nSe0-pellets): qmax: 2.8–11.3 |

(nSe0-pellets): 88.1 ± 5.3% |

|||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets: 0.01 g·mL−1 (ww); time: 30 min |

10–300 | qmax: 18.2 | 50% | [40] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cd(II) | pH: 4.5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 27 °C; amount of pellets (D): 0.1 g (dw); diameter of pellets: 1.58–2.03 mm; time: 18 h |

10–450 | qmax: 15.2 | Not reported | [46] |

| Pb(II) | 10–450 | qmax: 12.3 | ||||

| Binary system: Pb(II), Cd(II) |

Cd(II): 10–450; Pb(II): 25–50 |

Cd(II) qmax: 10–8.9 | ||||

| Pb(II): 10–450; Cd(II): 25–50 |

Pb(II) qmax: 8.2–4.5 | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | pH: 5.5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 27 °C; amount of pellets (L, Al. P): 2 g·L−1 (dw); diameter of pellets: 1.5–1.7 mm; time: 16 h |

50 | (L): qexp: 16.1 | 64.3% | [47] |

| (Al. P): qexp: 15.2–23.7 qmax: 144 |

60.6–94.7% | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | pH: 3–4; agitation: 200 rpm; T: 35 °C; amount of pellets (L, D): 90 mg (dw); time: 4 h | 5–50 | (L): qmax: 9 | Not reported | [48] |

| (D): qmax: 20 | ||||||

| pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 25 °C; age of pellets (Ac. P, Al. P): 41, 168 h |

20 | (Ac. P): qmax: 12.8–13.8 | ||||

| (Al. P): qmax: 20.1–48.2 | ||||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cu(II) | pH: 6; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 25 °C; time: 4 h | 100 | qmax: 3.9 | Not reported | [49] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cd(II) | pH: 6.2; T: 28 °C; amount of pellets: 0.2 g·mL−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 0.2–2 cm; time: 2 h | 1124 | qexp: 84.5 | 34% | [50] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Cu(II) | Column experiments; pH: 3, 4; total column volume: 620 mL; flow rate: 1mL·min−1; amount of pellets (L): pH 3: 3.93 g (dw) pH 4: 3.37 g (dw) |

100 | pH: 3 qexp: 1.9 |

Not reported | [34] |

| pH: 4 qexp: 7.9 |

||||||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Ni(II) | pH: 8; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 35 °C; amount of pellets (L, D, Al. P): 3 g (ww); time: 72 h |

500 | (L): qmax: 315.6 | Not reported | [51] |

| (D): qmax: 125.4 | ||||||

| (Al. P): qmax: 357.6 | ||||||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Cs | Air lift column system Liquid to solid ratio (v/v): 10:1 pH: 5; diameter of pellets: 5 mm; time: 3 h |

Cs: 13.3 | qmax: 82 | 41% | [43] |

| Sr | Sr: 8.8 | qmax: 88 | >90% | |||

| U | U: 23.8 | qmax: 180 | 44% | |||

| Rhizopus nigricans | Pb(II) | Batch stirred tank Agitation: 300 rpm; amount of pellets: 25–200 g·L−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 2.5 ± 0.5 mm |

20–300 | qmax: 83.5 | Not reported | [52] |

| Rhizopus nigricans | Li | pH: 5; agitation: 125 rpm; T: 22 ± 1 °C; diameter of pellets: 2.5 mm; time: 24 h | 10–1000 | qmax: 183.9 | Not reported | [53] |

| Al(III) | qmax: 163.0 | |||||

| Fe(II) | qmax: 466.4 | |||||

| Fe(III) | qmax: 407.7 | |||||

| Ni(II) | qmax: 201.2 | |||||

| Cu(II) | qmax: 360.4 | |||||

| Rhizopus nigricans | Zn(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 125 rpm; T: 22 ± 1 °C; diameter of pellets: 2.5 mm; time: 24 h | 10–1000 | qmax: 235.1 | Not reported | [53] |

| Sr(II) | qmax: 278.0 | |||||

| Ag | qmax: 451.9 | |||||

| Cd(II) | qmax: 302.6 | |||||

| Pb(II) | qmax: 403.2 | |||||

| Rhizopus oryzae | Cu(II) | pH: 4; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 25–45 °C; amount of pellets (Al. P): 1 g (ww); diameter of pellets: 1–1.2 mm | 10–300 | qmax: 52.9–61.7 | [40] | |

| Trametes versicolor | Cd(II) | pH: 6.2; T: 28 °C; amount of pellets: 0.2 g·mL−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 0.2–2 cm | 1124.1 | 109.5 | 43% | [50] |

3.1. Effect of pH on Biosorption of Metals

The solution pH affects the speciation of metal ions, and also influences the surface properties of the sorbents [38][41], affecting the dissociation of binding sites and their surface charge, the activity of functional groups (mainly carboxylate, phosphate, and amino groups) in the biomass [54], as well as the competition of metallic ions with hydronium ions for the adsorption sites [38].

The effect of pH in biosorption processes depends on the strain and the metal ion to be removed. Binupriya et al. [39] evaluated the biosorption of metal ions in aqueous solutions with pellets of Aspergillus japonicus; in the case of Ni(II), the removal increased as the pH increased from 2 to 10, reaching a maximum removal of 100% at pH 9. In the case of Fe(II), the removal improved as the pH increased from 2 to 6; at pH 6, the removal was 100%, and when the pH was extended above this value and until pH 10, the removal remained higher than 90%. This trend has also been reported for Zn removal by Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets [45], as the adsorption capacities increased as the pH values rose from 2 to 7. The maximum removal efficiencies (48.6 ± 4.5%) were observed at pH 7.0, which was attributed to the dissociation of protons from the carboxylic acid group, one of the major components of the fungal cell wall. As the pH of the aqueous solution increased, the dissociation of protons also augmented, as well as the presence of negatively-charged groups in fungal surface and therefore the number of binding sites available for complexation of metal cations [45]. Concerning the removal of U(VI) with Funalia trogii pellets, the optimum pH was 5, which was attributed to the presence of ligands such as amino, carboxyl, and phosphate groups on the surface of the pellets at this pH value [55]. The authors indicated that the decrease in the amount of metal absorbed at pH higher than 5 was due to the formation of uranyl carbonate complexes [55]. Concerning the biosorption of Cu, it has been reported that when pH value is higher than 5, the adsorption on fungal pellets decreases due to the precipitation of copper hydroxide [34][40]. As most metals complex and precipitate at alkaline pH values, biosorption is usually evaluated in a 2–7 pH range to attribute the metal removal only to the biosorption process.

On the other hand, at very acid pH values, low metal adsorption capacities have been reported, which is mainly attributed to the hydronium ions competing with the metal ions for the binding sites. For instance, the removal of Cu, Ni, and Zn is negligible at pH 3, due to the effects of the competition between the cations and the hydronium ions for the biosorption sites in Aspergillus niger pellets [38]. In the case of Cu, a low biosorption capacity was observed at pH values below 3.0 when alkali-pretreated and viable pellets of Rhizopus oryzae were tested [56]. In column experiments, Gabriel et al. [34] reported a low Cu biosorption capacity with pellets of Pleurotus ostreatus at pH 3 (1.92 mg·g−1) compared to the value obtained at pH 4 (7.92 mg·g−1). Many authors agree that the pH optimum for Cu biosorption is at 4–5 pH range [36][38][56]. Mishra and Malik [36] obtained the best metal uptake yields (79.8% and 77.2%) at pH 4 and 5, respectively, with Aspergillus lentulus pellets. For Rhizopus oryzae pellets, the maximum Cu adsorption capacities (52.91–61.73 mg·g−1) were reported at pH 4 [40]. In another study, the maximum Cu removal with alive pellets of Phanerochaete chrysosporium (50%) and with Funalia trogii pellets (61%) was obtained at pH 5 [40].

In the case of Cr(VI) biosorption, the removal by Aspergillus japonicus pellets decreased from 100 to 40% as the pH value increased from 2 to 10 Biosorption of meta [39]. Filipović-Kovačević et al. [38] reported that the biosorption of Cr(VI) on Aspergillus niger pellets followed this same trend, since the maximum capacity of adsorption was obtained at pH 2 and then it decreased as the pH increased from 2 to 7. This was explained by the speciation of Cr(VI), which predominates as HCrO4− at concentrations less than 500 mg·L−1 and low pH values, although another species as Cr2O72−, Cr3O102−, and Cr4O132− coexist in acid media [57]. As all these Cr(VI) species are negatively charged, a decrease in pH leads to a higher protonation of the fungal surface, creating a stronger attraction between the adsorbate and the biosorbent. Therefore, as the pH increases, the surface charge of the fungal pellets becomes negative, leading to weak bondings with the negatively-charged Cr species. Besides, in alkaline environments other negative ions such as OH- are likely to compete with the anion predominant at higher pH values (CrO42−) for the biosorption on the fungal biomass [57][58].

Finally, several works report a negligible effect of pH in the biosorption process. It is the case of As(III), for which almost complete removal was obtained at several concentrations of both Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets and adsorbate, while a negligible effect of pH values comprised between 5 and 9 was observed [44]. In preliminary experiments with Pb(II) and Aspergillus lentulus pellets, Mishra and Malik [36] concluded that pH did not significantly alter the metal uptake.

3.2. Effect of Initial Metal Concentration on Biosorption

Another important parameter in the biosorption of metals with fungal pellets is the initial metal concentration in the solution. On the one hand, if the metal biosorption and bioaccumulation of the metal are being evaluated in live pellets, its initial concentration can affect the growth of the pellets [36]. On the other hand, the initial concentration of metal ions in the solution plays a key role as a driving force to overcome the mass transfer resistance between the aqueous phase and the biosorbent [59].

Mishra and Malik [36] evaluated the growth of Aspergillus lentulus pellets in presence of Cu(II), Cr(III), Ni(II), and Pb(II). A lower biomass production was observed, compared to a control, when metals were added. The biomass growth reduced 19% in presence of 70 mg Ni2+·L−1; this reduction was of 76% when the metal concentration increased at 140 mg·L−1. In the same study, after five days of growth, the addition of 80 mg Cu2+·L−1 reduced 16% the pellets’ biomass, while this reduction was of 77% at 800 mg Cu2+·L−1.

The metal uptake capacity of Aspergillus lentulus was also evaluated as a function of the initial concentration of metal ions (Cu(II), Cr(III), Ni(II), and Pb(II)) in the medium [36]. The removal of Cu(II) and Ni(II) ions was enhanced by increasing the initial metal ion concentration. The maximum specific metal uptake was determined as 124.5 mg·g−1 (at 800 mg·L−1) for Cu(II), as 11 mg·g−1 (at 140 mg·L−1) for Ni(II), 331.5 mg·g−1 for Cr(III), and 1120.6 mg·g−1 for Pb(II) (at 4000 mg·L−1 for both metal ions) [36]. A high initial concentration provides an increased driving force to overcome all mass transfer resistance of metal ions between the aqueous and solid phase, resulting in a higher probability of collision between metal ions and biosorbents [36][59].

The biosorption capacity of Pb(II) (1120.6 mg·g−1) obtained with live Aspergillus lentulus pellets [36] is 70-fold higher than the values obtained with live pellets of Phanerochaete chrysosporium, namely 16 mg·g−1 [68], and around 120-fold higher than the capacity (9.0 mg·g−1) measured by Yetis et al. [48]. By using alkali-pretreated pellets of the same strain, low Pb(II) biosorption capacities were reported (15.2–23.7 mg·g−1 and 20.1–48.2 mg·g−1, respectively) [47][48]. This differences between adsorption capacities are mainly due to the initial metal concentration used (50 mg·L−1) in these works [47][48] compared to the (4000 mg·L−1) evaluated by Mishra and Malik [36].

An increase in the Ni concentration (from 100 to 500 mg·L−1) resulted in an approximately fivefold increase in the biosorption capacity of this metal onto Rhizopus arrhizus pellets from 61.2 to 348.8 mg·g−1. However, the biosorption capacity decreased when the nickel concentration exceeded 500 mg·L−1 [51].

Some general comments on the literature reviewed so far can be made. First of all, research work concerning the evaluation of fungal pellets for the biosorption of low concentrations of metal ions is scarce. The concentrations being evaluated should be as realistic as possible, and for some metals (i.e., precious metals or radionuclides) their concentrations in wastewater are hardly higher than 1–10 mg·L−1 [44]. Besides, other compounds that can intervene negatively in the biosorption processes of metals should be more explored, such as the most common anions present in groundwater and industrial effluents (i.e., chlorides, nitrates, fluorides, phosphates, and sulfates) [38]. In the Section 2.1.6, the few articles that have reported the interference of these anions and their competition with different metal ions will be discussed.

3.3. Effect of Diameter of Pellets on Biosorption of Metals

The pellet diameter determines the surface area of the biosorbent, which is a key factor in biosorption processes. It also determines the number of metal binding functional groups readily exposed to the metal ions in solution. Fu et al. [40] evaluated the effect of the diameter of Rhizopus oryzae pellets on the removal of Cu(II) at pH 4 and an initial concentration of 100 mg·L−1. The adsorption capacity decreased from 37.1 to 18.4 mg·g−1 when the diameter of the pellet increased from 0.4 mm to 2.0 mm. This was attributed to a decrease in the surface area, which was responsible for a lower availability of exposed binding sites in biomass of larger diameter. When the diameter was higher than 1.2 mm, the autolysis of the pellets was likely to further decrease the availability of metal-binding functional groups.

Li et al. [46] evaluated the effect of pellets diameter (from 1.32–1.57 mm to 3.5–5.50 mm) on the Cd adsorption on Phanerochaete chrysosporium, at pH 4.5, 25 °C, and an initial metal concentration of 50 mg·L−1. The maximum Cd uptake (15.2 mg·g−1) was obtained when the pellet diameter was comprised between 1.58 and 2.03 mm. As for Fu et al. [40], the adsorption capacity decreased to 9.86 mg·g−1 when the diameter of the pellet increased to 3.5–5.5 mm.

Gabriel et al. [34] also studied the Cu biosorption by pellets of different strains, namely Aspergillus carbonarius, Lepista nuda, Oudemansiella mucida, Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus, among others. Although the variety of conditions at which the adsorption experiments were carried out hinders the comparisons, it is noteworthy that some of the reviewed papers about Cu biosorption report the same environmental conditions, i.e., pH 4, 25 °C, and a stirring rate of 50 rpm. In these conditions, the highest adsorption capacities were observed for the following fungal species: O. mucida (8.8 mg·g−1), L. nuda (6.3 mg·g−1), P. cinnabarinus (5.1 mg·g−1), and P. ostreatus (4.8 mg·g−1). The differences in these values were attributed to dissimilarities in the cell wall composition and to the physical properties of the pellets. From a biotechnological point of view, the fungal pellets of O. mucida, P. chrysosporium, and P. ostreatus were considered as having the best mechanical properties among the species studied [34]. These pellets had a size big enough for handling (3–7 mm) but at the same time with an adequate surface area. Thus, due to their high adsorption capacity, ease of handling, and resistance to mechanical disintegration, these fungal species were deemed well-suited to environmental applications.

3.4. Effect of Pretreatment of Fungal Pellets on Biosorption of Metals

It has been reported that the biosorption capacities of fungal pellets can improve with the modification of their surface area, either with acid [51], alkaline [48], or thermal pretreatments [41]. Other strategies are based on the chemical modification of the pellet surface with ligands having oxygen donor atoms, such as amidoxime [55], or the immobilization of nanoparticles of some metals on the fungal pellet surface [42][45]. Table 2 summarizes the results of some studies that have evaluated the pretreatment effect on the biosorption of metals.

Table 2. Summary of some pretreatments used in metal biosorption studies.

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Pellet Pretreatment | Operational Conditions | Best Suited Pretreatment for Adsorption | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentinus edodes | Hg(II) Cd(II) Zn(II) |

Thermal treatment | Pellets were heated at 90 °C for 15 min. | Thermal treatment | [41] |

| Penicillium sp. | Sr(II) Th(IV) U(VI) |

Addition of nanoparticles of Fe3O4 | ~0.1 g of nano-Fe3O4 particles were added into a spore suspension cultivated at 140 rpm, 30 °C for 36 h. The mixed solution was incubated for further 72 h. | Fe3O4 addition | [42] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Zn | Addition of nanoparticles of Se (nSe0) | Pellets were grown with Na2SeO3 (10 mg Se L−1), 150 rpm, pH 4.5, and 30 °C for 96 h. | nSe0 addition | [45] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cd(II) | Chemical and thermal inactivation | Pellets were inactivated by formaldehyde cross-linking and subsequent boiling in alkaline conditions for 45 min. | Not compared | [46] |

| Pb(II) | |||||

| Binary system: Pb(II), Cd(II) |

|||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | Alkali pretreatment | Pellets were soaked in NaOH 0.1 M for 40 min. | Alkali pretreatment | [47] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | Autoclaving | Pellets were autoclaved (121 °C, 20 min). | Alkali pretreatment | [48] |

| Alkali pretreatment | Pellets were suspended in NaOH 0.1 M for 1 h. | ||||

| Acid pretreatment | Pellets were washed with HClO4 5 × 10−3 M for 5–40 min. | ||||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Ni(II) | Alkali pretreatment | Pellets were treated separately with NaOH 0.1 M or NaCl 0.1 M for 30 min. Living (untreated) biomass was tested as a blank. | None (living biomass was best suited for Ni adsorption) | [51] |

| Rhizopus oryzae | Cu(II) | Thermal and alkali pretreatment | Pellets were boiled in NaOH 0.2 M (1:10 w/w) for 15 min. | Not compared | [40] |

Some of the reasons for using dead or inactive pellets in metal biosorption are that maintaining the viability of the microbial cells during the process requires a continuous supply of nutrients, and that avoiding toxicity against the cells might need a certain control of the metal concentration. Therefore, the use of non-living microbial cells can eliminate these problems, while enabling the biomass regeneration and reuse for several cycles [60].

Bayramoglu and Arica [41] evaluated the removal of Hg(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II) with alive (active) and dead (heat-inactivated) pellets of Lentinus edodes. The surface areas of the alive and heat-inactivated fungal pellets were measured by the BET method and were found to be 0.89 and 1.18 m2·g−1 of fungal biomass, respectively. The surface area in the native pellets was increased after thermal treatment, which enhanced the biosorption of the metals evaluated. So, the heat-inactivated pellets showed better adsorption capacities for Hg (419.1 mg·g−1), Cd (299.4 mg·g−1), and Zn (63.3 mg·g−1) compared to the alive fungal pellets (358.1, 86.4, and 37.7 mg·g−1, respectively).

The chemical modification with amidoxime appears to increase the biomass surface area and to favor the adsorption of heavy metals, as reported for Trametes trogii pellets evaluated for the biosorption of U(VI) [55]. Maximum biosorption capacities of modified and native pellets were found to be 447 and 238 mg g−1, respectively. This was explained by the fact that the amidoxime pretreatment increased 3.3-fold the surface area of fungal pellets, as well as the total available surface amino groups (2.54 mmol·g−1 of dry modified biomass against 0.36 mmol·g−1 dry native biomass).

One of the most recent proposals for improving metal removal is the synergy between biosorbents and nanomaterials [45]. Particles in the nano-size range possess altered properties compared to their bulk materials, including larger surface areas, higher reactivities, and faster adsorption kinetics [42], which makes them particularly attractive as sorbents [61]. Recently, fungal pellets have been proposed as biomass carriers of nanoparticles to make up new biocomposites for the treatment of wastewater. Abundant functional groups on the mycelium surface provide the feasible environment for the assembly and enhance the dispersibility of nanoparticles [42]. Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets provided with nanosized Se showed to be better biosorbents as they removed more Zn (88.1 ± 5.3%) compared to Se- free fungal pellets (56.2 ± 2.8%) at pH 4.5 and an initial Zn concentration of 10 mg·L−1. This improvement in biosorption performance was attributed to a more negative surface charge density, and hence to a higher concentration of sorption sites [45].

Ding et al. [42] studied the immobilization of iron oxide nanoparticles in pellets of Penicillium sp., which showed the following advantages: the nano-Fe3O4 particles can uniformly grow on the surface of Penicillium sp. with no aggregation; Penicillium sp. can be used as the template to direct and control the structure of the nano-Fe3O4 from the micro-scale level; and fungal pellets are more environmentally-friendly and cost-effective than other reported templates. The sorption results for three radionuclides (Sr(II), Th(II), and U(VI)) on both the alive native pellets and the Fe3O4-pellets of Penicillium sp. are shown in Table 2. Yet the increase of sorption capacity for the composite fungus-Fe3O4 toward the radionuclides was not obvious, probably because some surface functional groups of Penicillium sp. were occupied by nano-Fe3O4, leading to a partial loss of the ability of binding with radionuclides.

3.5. Biosorption of Heavy Metals From Mixtures

Little attention has so far been given to the multi-component biosorption of metal ions. However, these studies are more environmentally-relevant than those carried out with single metal ions, because they reflect more closely the state of the actual aquatic media. In these multi-systems, the biosorption depends, as shown above, on the biosorbent surface features, physicochemical parameters such as the solution pH, and the initial concentrations of both the adsorbate and the adsorbent, but also on the number and characteristics of the involved ions, among other factors [46]. Some relevant studies dealing with multi-metal ion biosorption will be discussed below.

Lead represents a serious and well-known environmental issue, because it induces dysfunctions in the neurologic, renal, and reproductive systems, particularly in young children. It is often released with cadmium from certain chemical processes and battery manufacturing [46][62]. Li et al. [46] studied the competitive biosorption of Cd2+ and Pb2+ by pellets of P. chrysosporium in the optimal physicochemical conditions determined for each metal separately. The comparison between the competitive biosorption of Cd2+ and Pb2+ showed that the biosorption of Pb2+ by P. chrysosporium pellets was preferential to that of Cd2+. Since both electronegativity and ionic radius of Pb2+ were larger than Cd2+, there might be a stronger chemical and physical affinity for Pb2+ on P. chrysosporium.

Bayranoglu et al. [41] evaluated the biosorption of cadmium, mercury, and zinc, because these three metals are commonly discharged together in wastewater by many industrial activities; however, cadmium and mercury raise the largest human health concerns. Cadmium is classed as a human and animal carcinogen (group 1) by the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) [63]. As to mercury, it has been related to the induction of more than 250 symptoms [64]. The biosorption of the Cd2+, Hg2+, and Zn2+ multi-system was studied with dead and alive fungal pellets of Lentinus edodes [41]. For both types of pellets, and for all the metal ions (at individual concentrations varying from 25 to 600 mg·L−1), the highest adsorption capacity occurred at pH 6. Dead and alive pellets showed the same affinity order for the metal ions both individually and in mixture: Hg2+ > Cd2+ > Zn2+. In fact, the adsorption capacity of Hg2+ was one order of magnitude higher than the Zn2+ adsorption capacity in live pellets, and two orders of magnitude higher in inactivated pellets. The authors attributed this selectivity to differences in the ionic properties, such as electronegativity, ionic radius, or redox potential of these metals. Thus, larger ionic radius and more electronegative metal ions would result in greater adsorption efficiencies [65]. However, the overall adsorption capacity of the pellets (dead and alive) was lower in the multi-metal system than in the single-metal assays [41][65].

Mishra and Malik [36] evaluated the simultaneous removal of multiple metals from electroplating effluents using Aspergillus lentulus pellets. First, the tolerance of A. lentulus against Cr, Cu, Pb, and Ni was evaluated in synthetic solutions after 5 days of growth. The removals followed the trend Pb2+ (100%) > Cr3+ (79%) > Cu2+ (78%) > Ni2+ (42%). When the pellets were applied to the treatment of a real electroplating effluent, the metal concentrations decreased by 71%, 56%, and 100% for Cr, Cu, and Pb, respectively, within 11 days, thereby showing that in a multi-metal system the preferential uptake can be different to that observed for single metal ions.

3.6. Effect of Anions on the Biosorption of Metals

Domestic and industrial wastewaters usually contain significant amounts of different anions, that may influence the biosorption of heavy metals. Filipović-Kovačević et al. [38] studied the effect of adding separately Cl−, NO3−, SO42− and ClO4− on the removal of several metal ions. Among the anions added, only chlorides significantly decreased the efficiency of Cu2+, Zn2+, Ni2+ and CrO42− biosorption, i.e., more than 50%.

Pakshirajan et al. [44] evaluated the effect of interfering ions such as F-, Fe(III), Cl−, and NO3−, which are commonly present in groundwater, on As(III) removal by Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets. Among the studied ions, only Fe(III) significantly enhanced As(III) sorption. This was explained by the precipitation of Fe(III) as Fe(OH)3, which is already known to be involved in the removal of As(III) from aqueous solutions. At higher concentrations of F−and NO3− (1.5 and 75 mg·L−1, respectively), it was noticed that whereas F− enhanced the biosorption of As(III), NO3− reduced it. These different effects of fluoride and nitrate maybe attributed to differences in their reactivity towards the As(III) binding sites on the biosorbent, thereby influencing As(III) removal either positively or negatively.

4. Conclusions

Biosorption constitutes an eco-friendly technology for the removal of heavy metals, as important adsorption capacities have been reported for several of them. This is mainly due to the properties of the fungal cell wall, which possess a large variety of functional groups able to interact with heavy metals through various chemical forces. Moreover, fungal granules offer process advantages over disperse mycelia, such as an improved biomass separation from treated aqueous media.

Effort has been made to increase the biosorption efficiency by several biomass pretreatments, including thermal and acidic inactivation. The underlying hypothesis is that such pretreatments increase the number of surface binding sites. Besides, dead fungal cells are considered as an adequate solution to the toxicity or inhibition problems that alive cells could endure due to adverse operating conditions. Some pretreatments do increase the biomass adsorption sites and seem enhance the adsorption capacity towards some metals, but it is not always the case. From our perspective, dead fungal pellets, unable of biodegrading organic matter or bioaccumulating metals or nutrients, are not the best option for treating real, complex water or wastewater.

The biosorption of complex mixtures of pollutants on fungal pellets should be more explored, as well as the interfering effect of common anions such as chlorides, nitrates, carbonates or sulfates. Earlier reviews already signaled that, in spite of the profusely-available scientific literature available on fungal biosorption, there is a lack of studies carried out with real wastewater and at pilot and large scale. It is also necessary to propose studies for the post treatment of fungal biomass after being used in the treatment of water pollutants. Further research on these topics is needed to take full advantage of fungal biotechnology on improving the quality of aquatic ecosystems.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/w12041155

References

- Meritxell Riquelme; Jesús Aguirre; Salomón Bartnicki-García; Gerhard H. Braus; Michael Feldbrügge; Ursula Fleig; Wilhelm Hansberg; Alfredo Herrera-Estrella; Jörg Kämper; Ulrich Kück; et al. Fungal Morphogenesis, from the Polarized Growth of Hyphae to Complex Reproduction and Infection Structures. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2018, 82, e00068-17, 10.1128/mmbr.00068-17.

- Tao Lu; Qi-Lei Zhang; Shan-Jing Yao; Efficient decolorization of dye-containing wastewater using mycelial pellets formed of marine-derived Aspergillus niger. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2017, 25, 330-337, 10.1016/j.cjche.2016.08.010.

- Erika Jimena Espinosa-Ortiz; Eldon R. Rene; Kannan Pakshirajan; Eric. D. Van Hullebusch; Piet N.L. Lens; Fungal pelleted reactors in wastewater treatment: Applications and perspectives. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 283, 553-571, 10.1016/j.cej.2015.07.068.

- Maria Papagianni; Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes. Biotechnology Advances 2003, 22, 189-259, 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2003.09.005.

- Sarman Oktovianus Gultom; Bo Hu; Review of Microalgae Harvesting via Co-Pelletization with Filamentous Fungus. Energies 2013, 6, 5921-5939, 10.3390/en6115921.

- García-Reyes, M.; Beltrán-Hernández, R.I.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, G.A.; Coronel-Olivares, C.; Medina-Moreno, S.A.; Juárez-Santillán, L.F.; Lucho-Constantino, C.A.; Formation, morphology and biotechnological applications of filamentous fungal pellets: A review. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química 2017, 3, 703-720, .

- Hazrat Ali; Ezzat Khan; Muhammad Anwar Sajad; Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869-881, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.075.

- A. E. Burakov; Evgeny Galunin; A. E. Burakov; Anastasia Kucherova; Shilpi Agarwal; Alexey G. Tkachev; Vinod Kumar Gupta; Adsorption of heavy metals on conventional and nanostructured materials for wastewater treatment purposes: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 148, 702-712, 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.11.034.

- M.A. Barakat; New trends in removing heavy metals from industrial wastewater. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2011, 4, 361-377, 10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.07.019.

- Abbas, S.H.; Ismail, I.M.; Mostafa, T.M.; Sulaymon, A.H; Biosorption of heavy metals: A review. J. Chem. Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, 74–102, .

- Salem, H.M.; Eweida, E.A.; Farag, A. Heavy Metals in Drinking Water and Their Environmental Impact on Human Health; ICEHM2000; Cairo University: Giza, Egypt, 2000; pp. 542–556.

- S. Khan; Q. Cao; Y.M. Zheng; Y.Z. Huang; Yong-Guan Zhu; Health risks of heavy metals in contaminated soils and food crops irrigated with wastewater in Beijing, China. Environmental Pollution 2008, 152, 686-692, 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.056.

- Ehssan Nassef; Removal of Copper From Wastewater By Cementation From Simulated Leach Liquors. Journal of Biosensors & Bioelectronics 2015, 6, 1, 10.4172/2157-7048.1000214.

- Thangavel, P.; Subbhuraam, C.V; Phytoextraction: Role of hyperaccumulators in metal contaminated soils. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. Part B 2004, 70, 109–130, .

- Wuana, R.A.; Okeimen, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, riks and best available strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 2011.

- Memon, A.R.; Aktoprakligil, D.; Özdemír, A.; Vertii, A. Heavy metal accumulation and detoxification mechanisms in plants. Turk. J. Bot. 2001, 25, 111–121.

- Tariq, M.; Ali, M.; Shah, Z. Characteristics of industrial effluents and their possible impacts on quality of underground water. Soil Environ. 2006, 25, 64–69.

- Sardar Khan; Abd El-Latif Hesham; Min Qiao; Shafiqur Rehman; Ji-Zheng He; Effects of Cd and Pb on soil microbial community structure and activities. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2010, 17, 288-296, 10.1007/s11356-009-0134-4.

- Sandhya Babel; Tonni Agustiono Kurniawan; Cr(VI) removal from synthetic wastewater using coconut shell charcoal and commercial activated carbon modified with oxidizing agents and/or chitosan. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 951-967, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.10.001.

- Anuradha Mudipalli; Metals (Micro nutrients or toxicants) & Global Health.. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2008, 128, , .

- Nilanjana Das; Recovery of precious metals through biosorption — A review. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 103, 180-189, 10.1016/j.hydromet.2010.03.016.

- Alejandro Sánchez-Chardi; Ciro Alberto De Oliveira Ribeiro; Jacint Nadal; Metals in liver and kidneys and the effects of chronic exposure to pyrite mine pollution in the shrew Crocidura russula inhabiting the protected wetland of Doñana. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 387-394, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.03.036.

- Fenglian Fu; Qi Wang; Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2011, 92, 407-418, 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.011.

- H Duygu Özsoy; Halil Kumbur; Basudeb Saha; J. Hans Van Leeuwen; Use of Rhizopus oligosporus produced from food processing wastewater as a biosorbent for Cu(II) ions removal from the aqueous solutions. Bioresource Technology 2008, 99, 4943-4948, 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.017.

- Tonni Agustiono Kurniawan; Gilbert Y S Chan; Wai-Hung Lo; Sandhya Babel; Physico–chemical treatment techniques for wastewater laden with heavy metals. Chemical Engineering Journal 2006, 118, 83-98, 10.1016/j.cej.2006.01.015.

- Mudhoo, A.; Garg, V.K.; Wang, S; Removal of heavy metals by biosorption. Environ. Chem. 2011, 10, 109–117, .

- Maria Gavrilescu; Removal of Heavy Metals from the Environment by Biosorption. Engineering in Life Sciences 2004, 4, 219-232, 10.1002/elsc.200420026.

- S Babel; Low-cost adsorbents for heavy metals uptake from contaminated water: a review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2003, 97, 219-243, 10.1016/s0304-3894(02)00263-7.

- Kuber C. Bhainsa; Stanislaus F D'souza; Thorium biosorption by Aspergillus fumigatus, a filamentous fungal biomass. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 165, 670-676, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.10.033.

- Vieira, R.H.; Volesky, B; Biosorption: A solution to pollution?. Int. Microbiol. 2000, 3, 17–24, .

- Gadd, G.M; Interactions of fungi with toxic metals. New Phytol. 1993, 124, 25–60, .

- Tadeusz Skowroński; Jacek Pirszel; Barbara Pawlik-Skowrońska; Heavy Metal Removal by the Waste Biomass of Penicillium chrysogenum. Water Quality Research Journal 2001, 36, 793-803, 10.2166/wqrj.2001.042.

- Joseph M. Brady; John M. Tobin; Adsorption of metal ions by Rhizopus arrhizus biomass: Characterization studies. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 1994, 16, 671-675, 10.1016/0141-0229(94)90088-4.

- Jiri Gabriel; P. Baldrian; K. Hladikova; M. Hakova; Copper sorption by native and modified pellets of wood-rotting basidiomycetes. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2001, 32, 194-198, 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00888.x.

- Faryal, R.; Lodhi, A.; Hameed, A. Isolation, characterization and biosorption of zinc by indigenous fungal strains Aspergillus fumigatus RH05 and Aspergillus flavus RH07. Pak. J. Bot. 2006, 38, 817.

- Abhishek Mishra; Anushree Malik; Simultaneous bioaccumulation of multiple metals from electroplating effluent using Aspergillus lentulus. Water Research 2012, 46, 4991-4998, 10.1016/j.watres.2012.06.035.

- Jing-Yao Wang; Ting-Ting Cao; Fang-Yuan Li; Chong-Wei Cui; The comparison of biosorption characteristics between the two forms of Aspergillus niger strain. DESALINATION AND WATER TREATMENT 2017, 63, 172-180, 10.5004/dwt.2017.20181.

- Filipović-Kovačević, Ž.; Sipos, L.; Briški, F. Biosorption of chromium, copper, nickel and zinc onto fungal pellets of Aspergillus niger 405 from aqueous solutions. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2000, 38, 211–216.

- A. R. Binupriya; M. Sathishkumar; K. Swaminathan; E. S. Jeong; S. E. Yun; S. Pattabi; Biosorption of Metal Ions from Aqueous Solution and Electroplating Industry Wastewater by Aspergillus japonicus: Phytotoxicity Studies. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2006, 77, 219-227, 10.1007/s00128-006-1053-4.

- Sibel Kahraman; D. Asma (Hamamci); S. Erdemoğlu; Ö. Yeşilada; Biosorption of Copper(II) by Live and Dried Biomass of the White Rot FungiPhanerochaete chrysosporium andFunalia trogii. Engineering in Life Sciences 2005, 5, 72-77, 10.1002/elsc.200420057.

- Gulay Bayramoglu; M. Yakup Arıca; Removal of heavy mercury(II), cadmium(II) and zinc(II) metal ions by live and heat inactivated Lentinus edodes pellets. Chemical Engineering Journal 2008, 143, 133-140, 10.1016/j.cej.2008.01.002.

- Congcong Ding; Wencai Cheng; Yubing Sun; Xiangke Wang; Novel fungus-Fe3O4 bio-nanocomposites as high performance adsorbents for the removal of radionuclides. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2015, 295, 127-137, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.04.032.

- Louise Rome; Geoffrey M. Gadd; Use of pelleted and immobilized yeast and fungal biomass for heavy metal and radionuclide recovery. Journal of Industrial Microbiology 1991, 7, 97-104, 10.1007/bf01576071.

- Kannan Pakshirajan; Marta Izquierdo; Piet N.L. Lens; Arsenic(III) Removal at Low Concentrations by Biosorption usingPhanerochaete chrysosporiumPellets. Separation Science and Technology 2013, 48, 1111-1122, 10.1080/01496395.2012.723102.

- Erika Jimena Espinosa-Ortiz; Manisha Shakya; Eldon R. Rene; Eric D. Van Hullebusch; Piet N.L. Lens; Rohan Jain; Sorption of zinc onto elemental selenium nanoparticles immobilized in Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 21619-21630, 10.1007/s11356-016-7333-6.

- Qingbiao Li; Songtao Wu; Gang Liu; Xinkai Liao; Xu Deng; DaoHua Sun; Yuelin Hu; Yili Huang; Simultaneous biosorption of cadmium (II) and lead (II) ions by pretreated biomass of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Separation and Purification Technology 2004, 34, 135-142, 10.1016/s1383-5866(03)00187-4.

- Juan Wu; Qing-Biao Li; Biosorption of lead by Phanerochaete chrysosporium in the form of pellets. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2002, 14, 108–114, .

- Yetis, U.; Dolek, A.; Dilek, F.B.; Ozcengiz, G. The removal of Pb (II) by Phanerochaete chrysosporim. Water Res. 2000, 34, 4090–4100.

- Cho Sing; Jian Yu; Copper adsorption and removal from water by living mycelium of white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Water Research 1998, 32, 2746-2752, 10.1016/s0043-1354(98)00024-4.

- Jiri Gabriel; O. Kofro E Ová; P. Rychlovský; M. Kren Elok; O. Kofroňová; M. Krenźelok; Accumulation and Effect of Cadmium in the Wood-Rotting Basidiomycete Daedalea quercina. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 1996, 57, 383-390, 10.1007/s001289900202.

- Arifa Tahir; Sidra Zahid; Ni(ll) biosorption byRhizopus arrhizusEnv 3: the study of important parameters in biomass biosorption. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2008, 83, 1633-1638, 10.1002/jctb.1972.

- Kogej, A.; Pavko, A. Mathematical model of lead biosorption by Rhizopus nigricans pellets in a laboratory batch stirred tank. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2004, 18, 29–36.

- Kogej, A.; Pavko, A. Laboratory experiments of lead biosorption by self-immobilized Rhizopus nigricans pellets in the batch stirred tank reactor and the packed bed column. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2001, 15, 75–80.

- Jianlong Wang; Can Chen; Biosorbents for heavy metals removal and their future. Biotechnology Advances 2009, 27, 195-226, 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.11.002.

- Gulay Bayramoglu; M. Yakup Arica; M. Yakup Arıca; Amidoxime functionalized Trametes trogii pellets for removal of uranium(VI) from aqueous medium. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 2016, 307, 373-384, 10.1007/s10967-015-4224-0.

- Kuber C. Bhainsa; Stanislaus F D'souza; Removal of copper ions by the filamentous fungus, Rhizopus oryzae from aqueous solution. Bioresource Technology 2008, 99, 3829-3835, 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.032.

- G. Blázquez; F. Hernáinz; M. Calero; M.A. Martín-Lara; G. Tenorio; The effect of pH on the biosorption of Cr (III) and Cr (VI) with olive stone. Chemical Engineering Journal 2009, 148, 473-479, 10.1016/j.cej.2008.09.026.

- Mohammad Noorisepehr; Simin Nasseri; Mansur Zarrabi; Mohammad Reza Samarghandi; Abdeltif Amrane; Removal of Cr (III) from tanning effluent by Aspergillus niger in airlift bioreactor. Separation and Purification Technology 2012, 96, 256-262, 10.1016/j.seppur.2012.06.013.

- Aksu, Z. Equilibrium and kinetic modelling of cadmium (II) biosorption by Chlorella vulgaris in a batch system: Effect of temperature. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2001, 21, 285–294.

- Arthur Raj Binupriya; M. Sathishkumar; Dhamodaran Kavitha; Krishnaswamy Swaminathan; Sei-Eok Yun; Sung-Phil Mun; Experimental and Isothermal Studies on Sorption of Congo Red by Modified Mycelial Biomass of Wood-rotting Fungus. CLEAN - Soil, Air, Water 2007, 35, 143-150, 10.1002/clen.200700025.

- Ming Hua; Shujuan Zhang; Bingcai Pan; Weiming Zhang; Lu Lv; Quanxing Zhang; Heavy metal removal from water/wastewater by nanosized metal oxides: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2012, 211, 317-331, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.10.016.

- Qixiao Zhai; Arjan Narbad; Wei Chen; Dietary Strategies for the Treatment of Cadmium and Lead Toxicity. Nutrients 2015, 7, 552-571, 10.3390/nu7010552.

- Joe Luevano; Chendil Damodaran; A review of molecular events of cadmium-induced carcinogenesis.. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology and Oncology 2014, 33, 183-94, 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.2014011075.

- Kevin Rice; Ernest M. Walker; Miaozong Wu; Chris Gillette; E.R. Blough; Environmental Mercury and Its Toxic Effects. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health 2014, 47, 74-83, 10.3961/jpmph.2014.47.2.74.

- Abbas Sulaymon; Ahmed A. Mohammed; Tariq J. Al-Musawi; Removal of lead, cadmium, copper, and arsenic ions using biosorption: equilibrium and kinetic studies. DESALINATION AND WATER TREATMENT 2013, 51, 4424-4434, 10.1080/19443994.2013.769695.