1. Introduction

In 2015, an informal group within the OECD called the Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurs (WPSMEE) embarked on the task of identifying potential new sources for funding SMEs. The WPSMEE produced two documents: (1) the report “New Approaches to Economic Challenges” (NAEC), approved by the G20 finance ministers and Central Bank governors in February 2015; and (2) the document “G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing”, approved in November 2015

[1]. These studies point out the limitations of a conventional bank loan as a financing instrument for SMEs in general, and for innovative enterprises, start-ups, and fast-growing companies in particular. Similarly, OECD reports from 2017 and 2020 underscore that these companies significantly foster economic growth and innovation, which is why addressing their financial needs is of crucial importance

[2][3]. Moreover, this is the reason why people should still seek to broaden the range of financing instruments for innovative ventures, as the finance gap experienced by SMEs persists, in the spheres of both debt and equity

[4]. The OECD also emphasizes the ever-growing need to develop new instruments and markets, and the need to share experience and good practices in this area

[1]. The pool of alternative financing instruments includes crowdlending and equity crowdfunding (CF). The validity of crowdfunding as a key financing option is confirmed by the value of the acquired capital. CF projects raised a total of USD 17.2 billion in North America, USD 10.24 billion in Asia, and USD 6.48 billion in Europe. Data from the EU Startup Monitor of 2018 reveal that 18.1% of European start-ups finance their activity through crowdfunding, which places this instrument alongside operational cash flows (used by 15.7%) and government subsidies (20%) in terms of popularity

[5][6]. The Statista forecasts

[7] indicate that transaction value will reach the compound annual growth rate (CAGR 2020–2024) of 5.8%, which will generate an estimated total amount of USD 180.5 million in 2024. In 2020, an average campaign in the sector of social funding will earn USD 5270

[7]. All of these data point to further dynamic growth of this form of financing. It is no coincidence that in 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals were created, which were included in the United Nations Development Agenda 2030. Among the many goals of sustainable development are responsible consumption and production, as well as partnership for goals. Additionally, according to the concept of sustainable development in the Brundtland Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (un.org)

[8], one of the important elements of building sustainable development is connecting the environment and the economy in the decision-making process. At the same time, the UN Secretary General established the Task Force on Digital Financing of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of his broader Roadmap for Financing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: 2019–2021. In the final report, the group of experts indicated that one of the important forms of financing sustainable development goals is crowdfunding. Crowdfunding platforms have opened new avenues for aggregating atomized interests, enabling SMEs to overcome trust barriers and to act collectively in financing things they value

[9]. The innovation of CF lies in the fact that by using the latest IT technologies and CF platforms, entrepreneurs can obtain funds for financing activities and projects directly from the “crowd”. Bearing in mind the above, it is worth paying attention to the key elements of crowdfunding that distinguish it from other sources of financing. First, crowdfunding fills the funding gap at an early stage of development. Second, crowdfunding uses power of the Internet and social media. Third, it favours the testing and implementation of unique ideas among the public. Finally, it facilitates direct consumer involvement. As a result, in addition to the funds accumulated through CF, values of a different type are generated. In the researchers' opinion, it is necessary to identify those aspects of crowdfunding that can create significant value for SMEs. These can have an impact on the company’s development, including strategic financial decisions, and the willingness of companies to use CF as a means of obtaining financing.

In light of the hopes and recommendations for crowdfunding as an alternative financing option for start-ups and SMEs, it is becoming increasingly important to understand how its use affects the value of these enterprises, especially considering that in the literature review a gap was identified in such an approach. A better understanding of the shaping of corporate value through CF, including the impact of CF on financial value, may contribute to the sustainable development of companies. This research presents an analysis of reward-based crowdfunding, equity crowdfunding, and crowdlending as business models oriented towards marketing and product commercialisation

[10]; it aims to indicate to what extent these CF models generate added value for companies. In other words, the researchers ask about the appeal of this financing option for an entrepreneur interested in the context of value-based management and sustainability. The added value of the researchers' undertaking is the holistic perspective of the impact of crowdfunding on company value, as well as the selected point of view (of the entrepreneur/owner). Both result from the researchers' novel approach to extant research and analyses on the topic.

2. Co-Created Values in Crowdfunding for Sustainable Development of Enterprises

The concept of crowdfunding reveals three groups of participants: entrepreneurs, crowdfunders (investors/backers), and mediators (crowdfunding platforms (CFPs)). Characteristically, CF is readily accessible to both capital providers and entrepreneurs. The CFPs play a unique role in the system, ensuring not only resource acquisition, but also information exchange between entrepreneurs and investors. CF works on the basis of the mutual relations and interactions between both groups of agents involved. It is used to fund projects planned from start to finish, or for experimental interdisciplinary ventures where the final outcome is marked with a degree of uncertainty. The projects are designed in line with the guiding principle of win more–win more

[11][12][13]. In the light of the above, CF may be defined as an ecosystem

[14] relying on the following array of interactions:

-

Presentation of the idea or concept on a CFP;

-

Exchange of information and communication between the “crowd” and the “crowdfunders” through the platform;

-

The crowdfunders’ decision to pledge funds;

-

Rewards for the crowdfunders.

In principle, crowdfunding projects follow four basic business models

[15]:

-

Donation-based crowdfunding—which involves fundraising for philanthropic purposes, health-related projects, artistic endeavours, or research. The backers expect no pecuniary gain for their support;

-

Reward-based crowdfunding—which involves the co-financing of various projects in exchange for tangible or non-tangible rewards, such as T-shirts, or having the name of the backer posted on the campaign website. Reward-based crowdfunding may take the form of pre-purchase CF, where the backers buy the product at the development stage. Thus, the financing involves an exchange between the enterprise and the backers;

-

Equity crowdfunding—which involves stock investments. The capital is provided by investors looking to profit from their share in future cash flows. This model does not rely on consuming the company’s product as a reward for the invested capital;

-

Crowdlending—a lending-based type of crowdfunding where the investors, referred to as lenders, gain profit in the form of interest on the loans granted.

The review of CF models reveals that an enterprise that opts for this form of financing needs—apart from an interesting project—a good grasp of its operational capacities, external circumstances, the needs of clients, crowdfunding itself and its costs, and the operation of CFPs. While the backers of donation-based crowdfunding campaigns expect no tangible gain, and content themselves with the satisfaction that comes with helping others (utilitarian, intangible values), other business models involve an exchange of values that may be intangible (knowledge), tangible (services, products), or purely financial (interest). Therefore, the entrepreneur should make their decision by weighing up potential profits and costs relevant to their individual situation. The final argument that should tip the balance in favour of crowdfunding is not only the advantage of expected profits over costs. For an entrepreneur, the added value of crowdfunding may not only be financial, but also social.

2.1. Crowdfunding—A Constellation of Values

Adopting the definition of crowdfunding as an ecosystem seems to be advisable, because it takes into account all of its important features and elements; however, such an approach does not allow the use of the value chain method in the analysis of the created/co-created value. This is because value chain presupposes the sequential nature of value creation

[16][17]. Meanwhile, in the CF ecosystem, the relationships between individual components are more complex. Therefore, it is preferable to use the value constellation theory, which entertains various means of coordination, types of integration

[18][19][20], and mutual adaptations observed within the ecosystem. According to the value constellation theory, an enterprise establishing connections with other entities creates a constellation of agents, and their cooperation leads to the creation (co-creation) of value. Quero, Ventura, and Kelleher

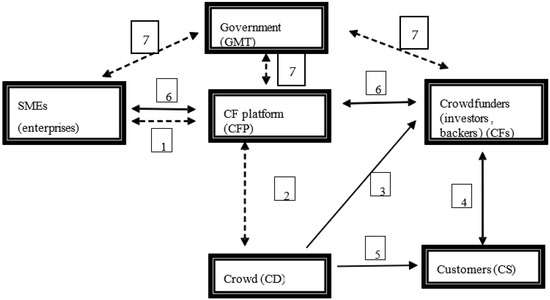

[18] performed an analysis of CF value at three levels—micro-context, meso-context, and macro-context—allowing them to trace mutual connections between agents and co-creation of values, but overlooking the owner’s perspective. The model the researchers propose complements existing research into value creation through CF, but references the co-created values against those of critical importance for SME owners. Drawing upon the ecosystem model, the researchers distinguish the following groups of agents: an SME, a CF platform (CFP), the crowd (CD), crowdfunders (CFs), clients (CS), and their mutual connections. Interactions between the agents are defined on the basis of the value constellation theory, as presented in

Figure 1.

As can be seen in Figure 1, no link is unidirectional. Even if the researchers can divide the processes into individual stages, as illustrated by numbers 1–6, each interaction prompts a response. In the figure, solid lines represent an interaction involving the transfer of funds and the delivery of a product or a crowd transfer. The connections made through actions taken on the CFP can be seen: (1) SME—CFP: a new product idea presented on the CFP (information flow) and exchange of information through CFP and crowd line; (2) CD—CFP and (3) CD—CFs: a group of investors emerges from the crowd; and finally, resource acquisition (6. CFs—CFP—SME). Dotted lines that link SME with CFP and the CD present the communication and information exchange alone. Solid lines (6) CFs—CFP—SME present exchange money, rewards, and payments between investors and SMEs. Processes do not necessarily lead to investor acquisition but, if the project is a success, they may provide a new group of clients who do not invest in the project but simply want to buy products, which is depicted as solid line (5) CD–CS: emergence of client groups and future investors eventually (line 4). The CF ecosystem is heavily influenced (7—dotted lines) by legal regulations established by the government (GMT). For instance, the authorities regulate financial law—which defines the scope of financing options available to SMEs and micro-enterprises for innovation—create legal frameworks for the existence of web platforms, and impose taxes, which concern not only the entrepreneurs and CFPs, but also investors.

Using the CF value constellation model (

Figure 1) and the seven Co-s model proposed by Quero, Ventura, and Kelleher

[18], the researchers have devised a map of value types co-created with reference to the interactions between groups of agents. According to the 7 Co-s model, crowdfunding leads to the co-creation of values such as co-ideation, co-design, co-evaluation of ideas, co-testing, co-launching, co-financing, and co-consumption. Within the constellation, the character of the connections/interactions between the agents is tied to the type of co-created value in question. The network of these mutual connections is shown in the researchers' relations matrix (

Table 1)

[18][20][21][22][23]. On this map what values are co-created with the interactions described above can be identified.

Table 1. Co-created values in CF as a result of interactions.

The co-created values may be divided into three main groups: those related to (1) strategy and product concept, including concept development, verification, and testing; (2) finance; and (3) production, market launch, and sales.

In the first group, the agents include entrepreneurs, the crowdfunding platform as a mediator, and the broadly understood crowd. Positive crowd response to the product and the prospect of active participation in product development may attract a group of active investors (resource providers). In that case, the entrepreneur has achieved the funding goal, and may proceed with production and sales. The crowd plays an important and unique role in the process. In the beginning, it participates in project design, assessment, and testing, which relate to interactions 1, 2, and 3. Then, it morphs into a capital provider (interaction 6). Finally, it becomes a group of consumers, which relates to interaction 4 or interaction 5. With the lively information flow and continuous communication at all stages—before resource acquisition, throughout the funding period, and during project implementation—all agents participate in the co-creation of values, with the influence of government on all of these agents. The process relies heavily on the CFP, which provides an arena for information exchange and communication between all participants, ensuring that everything runs smoothly from the technical, legal, and organisational standpoints. Therefore, apart from their role in fundraising, CFPs serve as useful marketing tools.

Let the researchers emphasise the differences in value co-creation arising from the business model employed in a given crowdfunding project. In reward-based crowdfunding, which relies on recompense or the pre-purchase mechanism, the capital is provided by customers. Consequently, these customers are referred to as backers (rather than investors), and their interactions correspond to interactions 4 and 5 in the value constellation model. Meanwhile, equity CF and crowdlending require the participation of investors, who provide capital and may or may not become customers. Alternatively, the enterprise may acquire customers who will not, however, pledge funds to the campaign. Therefore, value co-creation in equity CF and crowdlending is a more complex issue, as reflected in the value constellation model (interactions. 4, 5, and 6). A detailed analysis of values co-created in the CF ecosystem for SMEs is presented later in this research.

2.2. Crowdfunding —A Map of Values

For an enterprise, the choice of financing options is a critical decision

[21][22][23][24][25], contingent upon the selected business strategy. To analyse this strategy, Norton and Kaplan propose a balanced scorecard that includes four perspectives/areas of business activity—learning and growth, internal (operation), customer, and financial

[26] —and determines value drivers significant for each area

[26][27]. This method has the key advantage of measuring the factors that affect both financial and non-financial (intangible) value, and examining their mutual relations

[24]. A harmony between all of the perspectives is the main prerequisite for boosting company value. The value creation factors identified by Norton and Kaplan correspond to those proposed by Walters

[5][28] and Rappaport

[29], whereas the fundamental determinant of company value growth is the increased free cash flow. Based on free cash flow, the researchers can assess company value with EVA (economic value added)—a measure calculated with the following formula

[12][26][27]:

where: Tax = income tax rate; Cost of Capital = the cost of CFP management and other fundraising-related activities; Sales = the worth of sales generated by the CF campaign and its growth as compared to past performance in the period preceding the campaign; and Operating Costs = costs generated by CF related to the value of products sold and/or to the adjustments made to satisfy customer requirements.

In essence, to calculate EVA is to translate the operational performance of the enterprise into cash flow. This measure is used to assess short-term value growth—in an annual perspective at the maximum (as it relies on financial results)—and serves as an indicator of value growth or degradation for the owners. By determining which values co-created through CF may affect the value drivers in each perspective in the first place and, in the longer run, revenue and expenditures, the researchers will finally assess their impact on EVA.

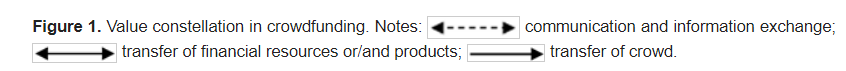

A visualisation of these connections is shown in Figure 2. The graphic consists of two areas: the first represents the non-financial activity (customer, internal, and learning perspectives) of the enterprise, including the spheres of knowledge and growth, whereas the other illustrates the sphere of finance. The map of value creation in the enterprise is simultaneously modelled, which serves to present the position of the remaining agents in relation to the indicated areas of value creation.

Table 2 shows that, with the exception of co-financing, all co-created values fall in the non-financial area. The arrows in Figure 2 pointing from the crowd towards various perspectives symbolise values co-created in the CF ecosystem that exert a particularly marked influence on the (non-financial) area in question.

Table 2. Co-created values in CF as a result of interactions.

Interaction

Co-Created Values |

1. SME—CFP |

2. CD—CFP |

3. CD—CF |

4. CFs—CS |

5. CD—CS |

6. CFs—CFP—SME |

| Co-ideation |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|

| Co-evaluation of ideas |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|

| Co-design |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|

| Co-testing |

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| Co-launch |

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| Co-consumption |

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| Co-financing |

|

|

|

x |

x |

x |

In the perspective of learning and growth, key value drivers include the human capital (e.g., knowledge, abilities, skills, staff motivation), information capital (various types of assets, databases, systems, and networks for knowledge acquisition), and organisational capital (including organisational culture, leadership, and the compatibility of people and the strategy). In the context of the interplay within the CF ecosystem and its value constellation, the key co-created values include co-ideation, co-design, and co-evaluation of ideas. Networking and crowdsourcing—both typically present in CF—allow greater access to tangible and intangible resources. Consequently, they are potentially helpful in acquiring knowledge or skills, which could mean life or death for the project

[30][31]. From an entrepreneur’s perspective, collective knowledge of the crowd may be exploited to verify project aims, crystallise the set of its distinguishing features, or polish the presentation. The degree of the enterprise’s involvement in co-creating value determines the success of the CF campaign and future development of the project. The values must remain equally important in all CF models. The information flow and communication between the crowd and the enterprise produce the signalling effect, which allows the investor/customer (who will eventually emerge from the crowd) to discount the products of future activities

[32]. Signalling fosters better decision-making in the scope of investments

[33] and/or purchases (risk mitigation)

[34]. Information flow and communication reduce the effect of asymmetrical information in relations between the investor and the entrepreneur, which mitigates the risk of failure for the investor

[33][34]. Thus, the values co-created in this sphere are also of material importance for other perspectives of the customer, finance, and internal processes within the enterprise.

Internal processes include operations (e.g., purchases, production, distribution, operational risk); customer management (e.g., customer selection, acquisition, retention); innovative processes (the identification of new opportunities for growth, new product portfolios, new projects and means for their implementation); and regulatory and social processes. The internal perspective involves product conceptualisation throughout the CF campaign and upon its conclusion, during the production stage. The focus falls on the opportunities to acquire and select clients, which facilitates market launch (co-launching), as well as the impact of co-created values (co-testing) on innovation processes concerning the product itself, its production, and its distribution. The entrepreneur’s expertise affects operational expenses on internal processes and the corporate image imparted to the customers

[35]. The verification of existing solutions against the expectations and ideas voiced by the crowd allows the enterprise to tailor its processes to the identified needs, through internal innovation and otherwise.

Internal processes depend on external circumstances created by the government—one of the agents included in the value constellation model. From the internal perspective, the government impacts the company’s operation through a range of legal and formal frameworks concerning business activity. Regardless of the selected business model, some level of value co-creation in this perspective is unavoidable due to its ties to the perspectives of learning and growth. Since product testing involves enterprises and members of the crowd, co-created values affect not only the internal perspective, but also that of the customer.

Customer perspective is a unique area of any fundraising strategy based on CF. Obviously, the link between the customers and capital providers is stronger in reward-based CF than in crowdlending or equity-based CF. However, in accordance with value-based management, maximising value drivers important for the customers will improve customer acquisition regardless of the selected CF model. The value drivers typically listed in this perspective include price, product quality, availability, quality of service, customer relations, and brand image. The Norton–Kaplan model prioritises active management of customer relations (the growth of sales), which—in the case of CF—is a natural corollary of the communication on the web platform and the fruit of the earlier value co-creation at the stages of ideation and evaluation of ideas. It is at this point that the price and sale volume first come under negotiation—far sooner than traditional business conventions would dictate. The crowd and the entrepreneur engage in an animated information exchange, which not only helps with the pricing but also fosters the customer–entrepreneur relationship

[36][37]. The entrepreneur gains recognition and may start building trust. Much like from the internal perspective, familiarity with customer expectations allows the entrepreneur to redirect the necessary resources to satisfying the identified needs and requirements (cost reduction)

[37][38]. Furthermore, it gives the entrepreneur a chance to investigate the opportunities for growth and assess the profitability of the new product.

2.3. Financial Perspective—The Impact of Co-Created Values on EVA

The financial perspective summarises how all of the decisions and activities included in other perspectives translate into cash flows. Value drivers include cash flows related to sales, operating costs, cost of capital, and interest rates. Figure 2 presents the necessary expenditures in these perspectives with line 3, while the revenue is marked with line 1, and cost of capital with line 2. A sales boost improves cash flows, whereas an increase in operating costs or the cost of capital has the opposite effect. Regulatory processes concerning tax rates and tax rules are another factor diminishing the amount of cash available to the owner. Upon analysis, the revenue generated through crowdfunding may be divided into two types: investment-based (in equity crowdfunding and crowdlending) and sales-based. Sales revenue is generated through client acquisition during the campaign (regardless of the adopted CF model) and product sales (as in reward-based crowdfunding). The generation of sales revenue adds the co-created value of co-financing. EVA rises together with the amount of resources collected from the investors and the number of clients acquired throughout and after the campaign. Campaign management, testing, product modification, production process adjustment, and distribution all entail operating costs, reducing the final income. The volume of operating costs hinges on activity in the perspectives of learning and growth, internal processes, and the customer.

The cost of capital in equity- and reward-based CF includes mainly the expenditure made on CFP management. Reward-based CF entails additional expenditure on the rewards. In the case of crowdlending, the cost of capital comprises CFP management plus interest. All of the relevant costs are compared against interest rates on loans

[36][37][38], allowing the evaluation of the profitability of launching a CF campaign. From the entrepreneur’s perspective, what matters is not only the CFP management cost (transactional cost), but also the potential funding amount, which will affect the cost of capital. The use of equity-based CF or crowdlending increases the value of equity or borrowed capital, and alters the capital ownership structure in the company. With reward-based crowdfunding, the capital structure remains unchanged, for the investors receive no shares and the resources acquired are non-refundable, as opposed to loans.

The use of CF mitigates business risk for both the investor/customer and the entrepreneur. It does not eliminate it altogether, since innovative projects typically funded through CF are high-risk by default. The risk–return relationship theory claims that the higher the risk, the higher the return on the investment

[37]. If the researchers consider this argument as decisive for their investment in CF, the researchers should expect return rates at a rather substantial level, which reveals the importance of the values co-created through CF. It is precisely these values that, by reducing the effect of asymmetrical information in the investor–entrepreneur relationship, mitigate the risk of project failure

[30][32]. If the added value arising from CF is to be positive, the generated revenue must exceed operating costs and the cost of capital. In that case, the use of CF may be deemed a success. However, if the crowdfunding campaign goes adrift or fails to raise the required amount of funds, the entrepreneur has to look for other financing options or reassess the entire process, from the concept itself to campaign management. Finally, a failed CF campaign may impair the company’s image.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13168767