The pink tide (Spanish: marea rosa, Portuguese: onda rosa, French: marée rose), or the turn to the left (Spanish: giro a la izquierda, Portuguese: volta à esquerda, French: tournant à gauche), was a political wave and perception of a turn towards left-wing governments in Latin American democracies moving away from the neoliberal economic model at the start of the 21st century. As a term, both phrases are used in contemporary 21st-century political analysis in the news media and elsewhere to refer to a move toward more economic progressive or social progressive policies in Latin America. Such governments have been referred to as "left-of-centre", "left-leaning", and "radical social-democratic". The Latin American countries viewed as part of this ideological trend have been referred to as pink tide nations, with the term post-neoliberalism or socialism of the 21st century being used to describe the movement as well. Some pink tide governments, such as those of Argentina , Brazil , and Venezuela, have been varyingly characterized as being "anti-American", as well as populist, for their rejection of the Washington Consensus, and as authoritarian, particularly in the case of Nicaragua and Venezuela by the 2010s. The pink tide was followed by the conservative wave, a political phenomenon that emerged in the early 2010s as a direct reaction to the pink tide. Some authors have proposed that there are multiple distinct pink tides rather than a single one, with the first pink tide happening during the late 1990s and early 2000s, and a second pink tide encompassing the elections of the late 2010s to early 2020s. A resurgence of the pink tide was kicked off by Mexico in 2018 and Argentina in 2019, and further established by Bolivia in 2020, along with Peru, Honduras, and Chile in 2021, and Colombia in 2022, with the first left-wing president-elect in Colombia's history, according to analysts.

- political analysis

- post-neoliberalism

- populist

1. Background

During the Cold War, a series of left-leaning governments were elected in Latin America.[1] These governments faced coups sponsored by the United States government as part of its geostrategic interest in the region.[2][3][4] Among these were Guatemala in 1954, Brazil in 1964, Chile in 1973, and Argentina in 1976. All of these coups were followed by United States-backed and sponsored right-wing, military dictatorships as part of the United States government's Operation Condor.[1][3][4]

These authoritarian regimes committed several human rights violations including illegal detentions of political opponents, tortures, disappearances, and child trafficking.[5] As these regimes started to decline due to international pressure, internal outcry in the United States from the population due to the involvement in the atrocities forced Washington to relinquish its support for them. New democratic processes began during the late 1970s and up to the early 1990s.[6]

With the exception of Costa Rica, virtually all Latin American countries had at least one experience with a United States-supported dictator:[7] Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, the Somoza family in Nicaragua, Tiburcio Carias Andino in Honduras, Carlos Castillo Armas and Efraín Ríos Montt in Guatemala, Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez in El Salvador, Manuel Noriega in Panama, Hugo Banzer in Bolivia, Juan María Bordaberry in Uruguay, Jorge Rafael Videla in Argentina , Augusto Pinochet in Chile , Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, François Duvalier in Haiti, Artur da Costa e Silva and his successor Emílio Garrastazu Médici in Brazil , Manuel Odria and Alberto Fujimori in Peru, the Institutional Revolutionary Party in Mexico,[8] Laureano Gomez and Rojas Pinilla in Colombia,[9] and Marcos Pérez Jiménez in Venezuela,[10] which caused a strong anti-American sentiment in wide sectors of the population.[11][12][13]

2. History

2.1. Rise of the Left: 1990s and 2000s

Following the third wave of democratization in the 1980s, the institutionalisation of electoral competition in Latin America opened up the possibility for the left to ascend to power. For much of the region's history, formal electoral contestation excluded leftist movements, first through limited suffrage and later through military intervention and repression during the second half of the 20th century.[14] The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War changed the geopolitical environment, as many revolutionary movements vanished, and the left embraced the core tenets of capitalism. In turn, the United States no longer perceived leftist governments as a security threat, creating a political opening for the left.[15]

In the 1990s, as the Latin American elite no longer feared a communist takeover of their assets, the left exploited this opportunity to solidify their base, run for local offices, and gain experience governing on the local level. At the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, the region's initial unsuccessful attempts with the neoliberal policies of privatisation, cuts in social spending, and foreign investment left countries with high levels of unemployment, inflation, and rising social inequality.[16] This period saw increasing numbers of people working in the informal economy and suffering material insecurity, and ties between the working classes and the traditional political parties weakening, resulting in a growth of mass protest against the negative social effects of these policies, such as the piqueteros in Argentina, and in Bolivia indigenous and peasant movements rooted among small coca farmers, or cocaleros, whose activism culminated in the Bolivian gas conflict of the early-to-mid 2000s.[17] The left's social platforms, which were centered on economic change and redistributive policies, offered an attractive alternative that mobilized large sectors of the population across the region, who voted leftist leaders into office.[18]

The pink tide was led by Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, who was elected into the presidency in 1998.[19] According to Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a pink tide president herself, Chávez of Venezuela (inaugurated 1999), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil (inaugurated 2003) and Evo Morales of Bolivia (inaugurated 2006) were "the three musketeers" of the left in South America.[20] National policies among the left in Latin America are divided between the styles of Chávez and Lula as the latter not only focused on those affected by inequality, but also catered to private enterprises and global capital.[21]

Commodities Boom and Growth

With the difficulties facing emerging markets across the world at the time, Latin Americans turned away from liberal economics and elected leftist leaders who had recently turned toward more democratic processes.[22] The popularity of such leftist governments relied upon by their ability to use the 2000s commodities boom to initiate populist policies,[23][24] such as those used by the Bolivarian government in Venezuela.[25] According to Daniel Lansberg, this resulted in "high public expectations in regard to continuing economic growth, subsidies, and social services".[24] With China becoming a more industrialized nation at the same time and requiring resources for its growing economy, it took advantage of the strained relations with the United States and partnered with the leftist governments in Latin America.[23][26] South America in particular initially saw a drop in inequality and a growth in its economy as a result of Chinese commodity trade.[26]

As the prices of commodities lowered into the 2010s, coupled with overspending with little savings by pink tide governments, policies became unsustainable and supporters became disenchanted, eventually leading to the rejection of leftist governments.[24][27] Analysts state that such unsustainable policies were more apparent in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela,[26][27] who received Chinese funds without any oversight.[26][28] As a result, some scholars have stated that the pink tide's rise and fall was "a byproduct of the commodity cycle's acceleration and decadence".[23]

Some pink tide governments, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, allegedly ignored international sanctions against Iran, allowing the Iranian government access to funds bypassing sanctions as well as resources such as uranium for the Iranian nuclear program.[29]

2.2. End of Commodity Boom and Decline: 2010s

Chávez, who was seen as having "dreams of continental domination", was determined to be a threat to his own people according to Michael Reid in American magazine, Foreign Affairs, with his influence reaching a peak in 2007.[30] The interest in Chávez waned after his dependence on oil revenue led Venezuela into an economic crisis and as he grew increasingly authoritarian.[30] The death of Chávez in 2013 left the most radical wing without a clear leader as Nicolás Maduro did not have the international influence of his predecessor. By the mid-2010s, Chinese investment in Latin America had also begun to decline,[26] especially following the 2015–16 Chinese stock market turbulence.

In 2015, the shift away from the left became more pronounced in Latin America, with The Economist saying the pink tide had ebbed[31] and Vice News stating that 2015 was "The Year the 'Pink Tide' Turned".[20] In that year's Argentine general election, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's favoured candidate for the presidency Daniel Scioli was defeated by his centre-right opponent Mauricio Macri, against a background of rising inflation, reductions in GDP, and declining prices for soybeans - a key export for the country, leading to falls in public revenues and social spending. Shortly afterwards the impeachment of Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff began, culminating in her removal from office. In Ecuador, retiring president Rafael Correa's successor was his vice-president, Lenín Moreno, who took a narrow victory in the 2017 Ecuadorian general election, a win that received a negative reaction from the business community at home and abroad: however, after his election, Moreno shifted his positions rightwards, resulting in Correa branding his former deputy as "a traitor" and "a wolf in sheep's clothing".[17][32]

By 2016, the decline of the pink tide saw an emergence of a "new right" in Latin America,[33] with The New York Times stating "Latin America's leftist ramparts appear to be crumbling because of widespread corruption, a slowdown in China's economy and poor economic choices", with the newspaper elaborating that leftist leaders did not diversify economies, had unsustainable welfare policies and disregarded democratic behaviors.[34] In mid-2016, the Harvard International Review stated that "South America, a historical bastion of populism, has always had a penchant for the left, but the continent's predilection for unsustainable welfarism might be approaching a dramatic end".[35]

2.3. Resurgence Since Late 2010s

Although the conservative wave weakened the pink tide and restored right-wing governments across Latin America throughout the 2010s, some countries have pushed back against the trend in recent years and elected more left-leaning leaders, such as Mexico with the electoral victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the 2018 Mexican general election and Argentina where the incumbent right-wing president Mauricio Macri lost against centre-left challenger Alberto Fernández (Peronist) in the 2019 Argentine general election.[36][37][38] This development has been strengthened by the landslide victory of the left-wing Movement for Socialism and its presidential candidate Luis Arce in Bolivia in the 2020 Bolivian general election.[39][40]

This trend continued throughout 2021 and 2022, when multiple left wing leaders won elections in Latin America. In the 2021 Peruvian general election, Peru elected the indigenous, socialist union leader Pedro Castillo in contrast to the previous leaders who embraced neoliberal populism.[41] In the 2021 Honduran general election held in November, leftist Xiomara Castro was elected president of Honduras,[42] and weeks later leftist Gabriel Boric won the 2021 Chilean general election to become the new president of Chile .[43] The 2022 Colombian presidential election was won by leftist Gustavo Petro,[44] making him the first left-wing president of Colombia in the country's 212-year history since independence in 1810 when inaugurated on 7 August 2022.[45][46] A series of violent protests against austerity measures and income inequality scattered throughout Latin America have also recently occurred including the 2019–20 Chilean protests, 2019–2020 Colombian protests, 2018–19 Haitian protests, 2019 Ecuadorian protests, and the 2021 Colombian protests.[36][47]

The pink tide governments aimed to improve the welfare of the constituencies that brought them to power, which they attempted through measures intended to increase wages, such as raising minimum wages, and softening the effects of neoliberal economic policies through expanding welfare spending, such as subsidizing basic services and providing cash transfers to vulnerable groups like the unemployed, mothers outside of formal employment, and the precariat.[17] In Venezuela, the first pink tide government of Chávez increased spending on social welfare, housing, and local infrastructures, and established the Bolivarian missions, decentralised programmes that delivered free services in fields, such as healthcare and education, as well as subsidised food distribution.[17]

Before Lula's election, Brazil suffered from one of the highest rates of poverty in the Americas, with the infamous favelas known internationally for its levels of extreme poverty, malnutrition, and health problems. Extreme poverty was also a problem in rural areas. During Lula's presidency several social programs like Zero Hunger (Fome Zero) were praised internationally for reducing hunger in Brazil,[48] poverty, and inequality, while also improving the health and education of the population.[48][49] Around 29 million people became middle class during Lula's eight years tenure.[49] During Lula's government, Brazil became an economic power and member of BRICS.[48][49] Lula ended his tenure with 80% approval ratings.[50]

In Argentina, the administrations of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner restored sectoral collective bargaining, strengthening trade unions: unionisation increased from 20 percent of the workforce in the 1990s to 30 percent in the 2010s, and wages rose for an increasing proportion of the working class.[17] Universal allocation per child, a conditional cash transfer programme, was introduced in 2009 for families without formal employment and earning less than the minimum wage who ensured their children attended school, received vaccines, and underwent health checks;[51] it covered over two million poor families by 2013,[17] and 29 percent of all Argentinian children by 2015. A 2015 analysis by staff at Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council estimated that the programme had increased school attendance for children between the ages of 15 to 17 by 3.9 percent.[51] The Kirchners also increased social spending significantly: upon Fernández de Kirchner leaving office in 2015, Argentina had the second highest level of social spending as a percentage of GDP in Latin America, behind only Chile. Their administrations also achieved a drop of 20 percentage points in the proportion of the population living on three US dollars a day or less. As a result, Argentina also became one of the most equal countries in the region according to its Gini coefficient.[17]

In Bolivia, Morales's government was praised internationally for its reduction of poverty, increases in economic growth,[52] and the improvement of indigenous, women,[53] and LGBTI rights,[54] in the very traditionally-minded Bolivian society. During his first five years in office, Bolivia's Gini coefficient saw an unusually sharp reduction from 0.6 to 0.47, indicating a significant drop in income inequality.[17] Rafael Correa, economist from the University of Illinois,[55] was won the 2006 Ecuadorian general election following the harsh economic crisis and social turmoil that caused right-wing Lucio Gutiérrez resignation as president. Correa, a practicing Catholic influenced by liberation theology,[55] was pragmatic in his economical approach in a similar manner to Morales in Bolivia,[19] and Ecuador soon experienced a non-precedent economic growth that bolstered Correa's popularity to the point that he was the most popular president of the Americas' for several years in a row,[55] with an approval rate between 60 and 85%.[56] In Paraguay, Lugo's government was praised for its social reforms, including investments in low-income housing,[57] the introduction of free treatment in public hospitals,[58][59] the introduction of cash transfers for Paraguay's most impoverished citizens,[60] and indigenous rights.[61]

Some of the initial results after the first pink tide governments were elected in Latin America included a reduction in the income gap,[62] unemployment, extreme poverty,[62] malnutrition and hunger,[63][64] and rapid increase in literacy.[63] The decrease in these indicators during the same period of time happened faster than in non-pink tide governments.[65] Several of countries ruled by pink tide governments, such as Bolivia, Costa Rica,[66] Ecuador,[67][68] El Salvador, and Nicaragua,[69] among others, experienced notable economic growth during this period. Both Bolivia and El Salvador also saw a notable reduction in poverty according to the World Bank.[70][71] Economic hardships occurred in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela, as oil and commodity prices declined and because of their unsustainable policies according to analysts.[26][27][72] In regard to the economic situation, the president of Inter-American Dialogue, Michael Shifter, stated: "The United States–Cuban Thaw occurred with Cuba reapproaching the United States when Cuba's main international partner, Venezuela, began experiencing economic hardships."[73][74]

3. Political Outcome

Following the initiation of the pink tide's policies, the relationship between both left-leaning and right-leaning governments and the public changed.[75] As leftist governments took power in the region, rising commodity prices funded their welfare policies, which lowered inequality and assisted indigenous rights.[75] These policies of leftist governments in the 2000s eventually declined in popularity, resulting in the election of more conservative governments in the 2010s.[75] Some political analysts consider that enduring legacies from the pink tide changed the location of Latin America's center of the political spectrum,[76] forcing right-wing candidates and succeeding governments to also adopt at least some welfare-oriented policies.[75]

Under the Obama administration, which held a less interventionist approach to the region after recognizing that interference would only boost the popularity of populist pink tide leaders like Chávez, Latin American approval of the United States began to improve as well.[77] By the mid-2010s, "negative views of China were widespread" due to the substandard conditions of Chinese goods, professional actions deemed unjust, cultural differences, damage to the Latin American environment and perceptions of Chinese interventionism.[78]

4. Term

As a term, the pink tide had become prominent in contemporary discussion of Latin American politics in the early 21st century. Origins of the term may be linked to a statement by Larry Rohter, a New York Times reporter in Montevideo who characterized the 2004 Uruguayan general election of Tabaré Vázquez as the president of Uruguay as "not so much a red tide ... as a pink one".[79] The term seems to be a play on words based on red tide—a biological phenomenon of an algal bloom rather than a political one—with red, a color long associated with communism, especially as part of the Red Scare and red-baiting in the United States, being replaced with the lighter tone of pink to indicate the more moderate socialist ideas that gained strength.[80]

Despite the presence of a number of Latin American governments that professed to embracing left-wing politics, it is difficult to categorize Latin American states "according to dominant political tendencies" like red states and blue states in the United States.[80] While this political shift was difficult to quantify, its effects were widely noticed. According to the Institute for Policy Studies, a left-wing think-tank based in Washington, D.C., 2006 meetings of the South American Summit of Nations and the Social Forum for the Integration of Peoples demonstrated that certain discussions that used to take place on the margins of the dominant discourse of neoliberalism, which moved to the center of public sphere and debate.[80]

In the 2011 book The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience, Isbester states: "Ultimately, the term 'the Pink Tide' is not a useful analytical tool as it encompasses too wide a range of governments and policies. It includes those actively overturning neoliberalism (Chávez and Morales), those reforming neoliberalism (Lula), those attempting a confusing mixture of both (the Kirchners and Correa), those having rhetoric but lacking the ability to accomplish much (Toledo), and those using anti-neoliberal rhetoric to consolidate power through non-democratic mechanisms (Ortega)."[76]

5. Reception

In 2006, The Arizona Republic recognized the growing pink tide, stating: "A couple of decades ago, the region, long considered part of the United States' backyard, was basking in a resurgence of democracy, sending military despots back to their barracks", further recognizing the "disfavor" with the United States and the concerns of "a wave of nationalist, leftist leaders washing across Latin America in a 'pink tide'" among United States officials.[81]

A 2007 report from the Inter Press Service news agency said how "elections results in Latin America appear to have confirmed a left-wing populist and anti-U.S. trend – the so-called 'pink tide' – which ... poses serious threats to Washington's multibillion-dollar anti-drug effort in the Andes".[82]

In 2014, Albrecht Koschützke and Hajo Lanz, directors of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation for Central America, discussed the "hope for greater social justice and a more participatory democracy" following the election of leftist leaders, though the foundation recognized that such elections "still do not mean a shift to the left", but that they are "the result of an ostensible loss of prestige from the right-wing parties that have traditionally ruled".[83]

Writing in Americas Quarterly after the election of Pedro Castillo in 2021, Paul J. Angelo and Will Freeman warned of the risk of Latin American left-wing politicians embracing what they dubbed "regressive social values" and "leaning into traditionally conservative positions on gender equality, abortion access, LGBTQ rights, immigration, and the environment". They cited Castillo blaming Peru's femicides on male "idleness" and criticizing what he called "gender ideology" taught in Peruvian schools, as well as Ecuador, governed by left-wing leaders for almost twenty years, having one of the strictest anti-abortion laws worldwide. On immigration, they mentioned Mexico's southern border militarization to stop Central American migrant caravans and Castillo's proposal to give undocumented migrants 72 hours to leave the country after taking office, while on the environment they cited Ecuadorian progressive presidential candidate Andrés Arauz insisting on oil drilling in the Amazon, as well as the Bolivian president Luis Arce allowing agribusinesses unchecked with deforestation.[84]

6. Heads of the State and Government

6.1. Presidents

Below are left-wing and centre-left presidents elected in Latin America since 1999.[85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101]

Centre-left presidents are marked with * while Venezuela is under a presidential crisis since 2019, indicated with ‡.

Néstor Kirchner

2003–2007

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1739905

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

2007–2015

By Unknown author - https://www.senado.gob.ar/prensa/galeria/VerAlbum/7348, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102403540

Alberto Fernández *

2019–present

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1102509

Luis Arce

2020–present

By Government of Bolivia - Plurinational Legislative Assembly, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115248823

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva *

2003–2010

By Ricardo Stuckert / Presidência da República. - Agência Brasil (Secretaria de Imprensa e Divulgação)., CC BY 3.0 br, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74123847

Dilma Rousseff *

2011–2016

By Palácio do Planalto, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12696743

Ricardo Lagos *

2000–2006

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1375935

Michelle Bachelet *

2006–2010

2014–2018

By Gobierno de Chile, CC BY 3.0 cl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47646203

Gabriel Boric

2022–present

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1455553

Gustavo Petro

2022–present

By Departamento Nacional de Planeación - Foto Oficial Presidente Gustavo Petro, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=122382638

Rafael Correa

2007–2017

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1896865

Mauricio Funes *

2009–2014

By Wilson Dias/Abr - http://www.agenciabrasil.gov.br/media/imagens/2008/05/21/1952WD203.jpg/view (cropped - lossless - by User:High on a tree), CC BY 3.0 br, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4286187

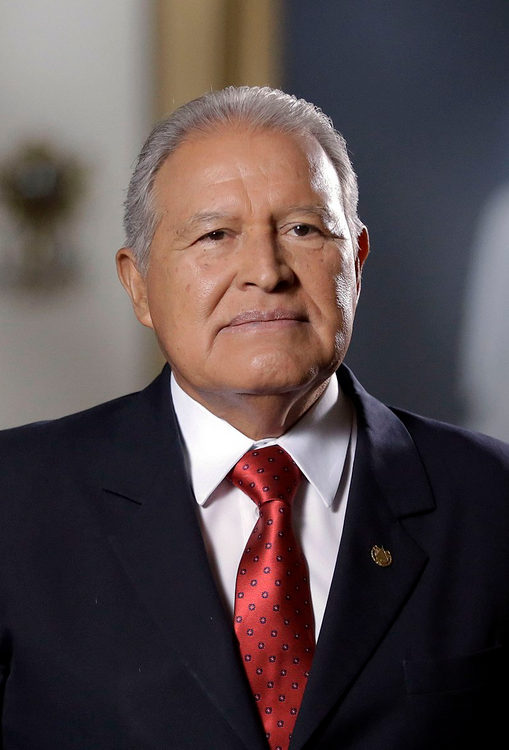

Salvador Sánchez Cerén

2014–2019

By Presidencia El Salvador from San Salvador, El Salvador, América Central - Cadena 12, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61606520

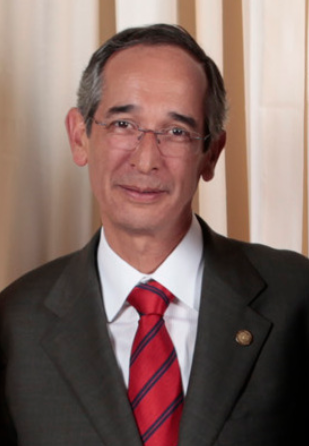

Álvaro Colom *

2008–2012

By Official White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson - https://www.flickr.com/photos/statephotos/3949367397, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68313809

Manuel Zelaya

2006–2009

http://www.agenciabrasil.gov.br/media/imagens/2009/08/12/1900jc330a.jpg/view, CC BY 3.0 br, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7548514

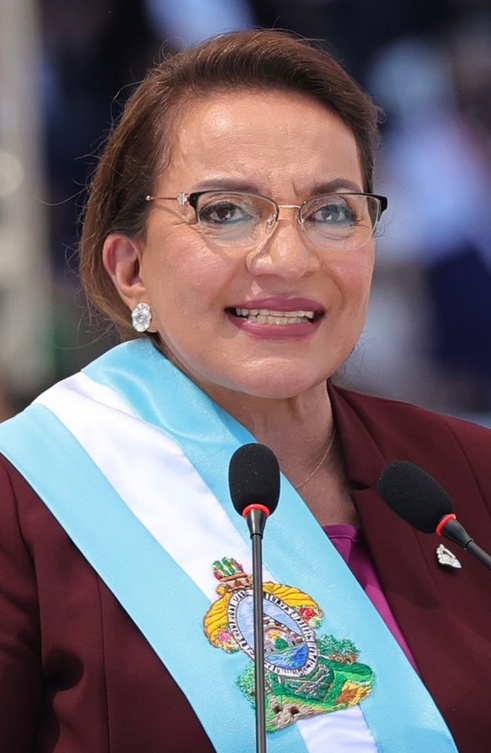

Xiomara Castro

2022–present

By 總統府 - https://www.flickr.com/photos/presidentialoffice/51847818640/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114969595

Andrés Manuel López Obrador *

2018–present

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2110583

Daniel Ortega

2007–present

By Presidencia de la República Mexicana - https://www.flickr.com/photos/presidenciamx/12199765064/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=112370900

Martín Torrijos *

2004–2009

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1161987

Laurentino Cortizo *

2019–present

By 首相官邸ホームページ, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115532962

Fernando Lugo *

2008–2012

By FernandoLugoAPC2008, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21196452

Ollanta Humala *

2011–2016

By Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Perú - https://www.flickr.com/photos/cancilleriadeperu/24396960920/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84852733

Pedro Castillo

2021–present

By Presidencia de la República del Perú - Image thumbnail of "Reunión del mandatario Pedro Castillo con el presidente del directorio del BCR, Julio Velarde", CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=109106343

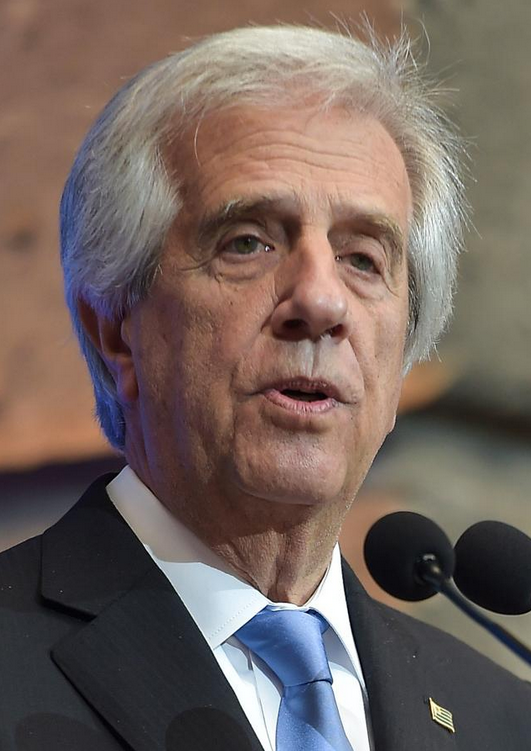

Tabaré Vázquez *

2005–2010

2015–2020

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1815690

José Mujica *

2010–2015

By Senado Federal - Solenidades. Homenagens, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83300507

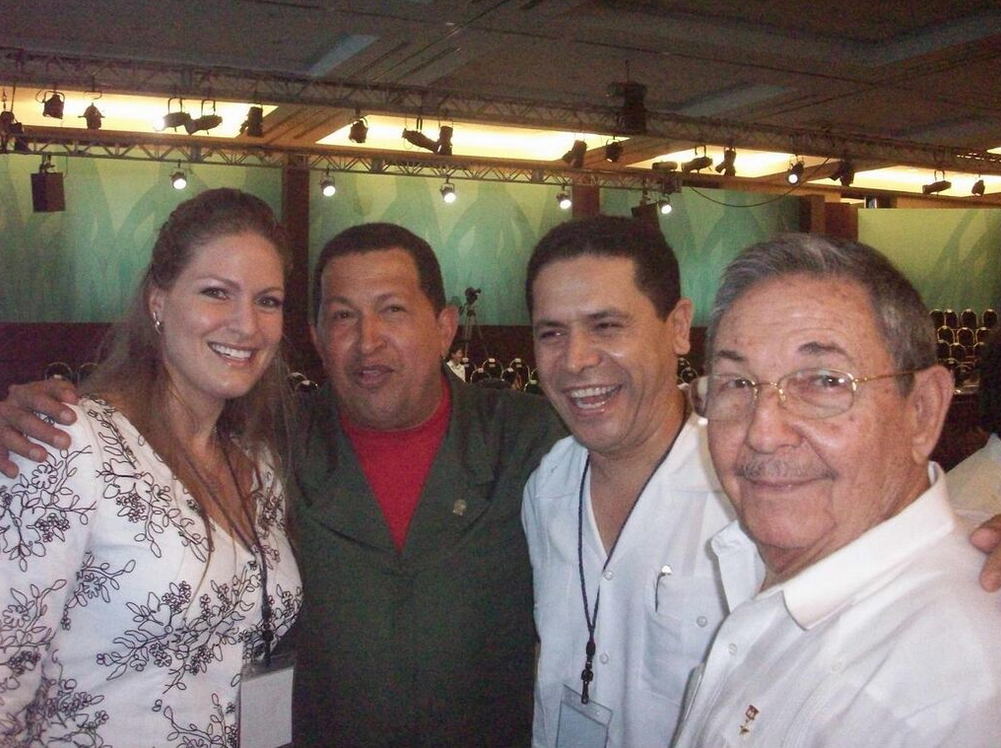

Hugo Chávez

1999–2013

By Office of the President of Brazil - Flickr: Brasília - DF, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38130461

Nicolás Maduro‡

2013–present

By Khamenei.ir, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=120463851

6.2. Disputed Pink Tide Leaders

The following left-wing and centre-left presidents, prime ministers, and other heads of governments, are sometimes included as part of the pink tide and sometimes excluded, either because the countries they lead are in the broader Latin America and the Caribbean region but are not technically part of Latin America or the leaders in question do not nescessarily fit under the definition of the pink tide.[103][104][105][106][107][108][109]

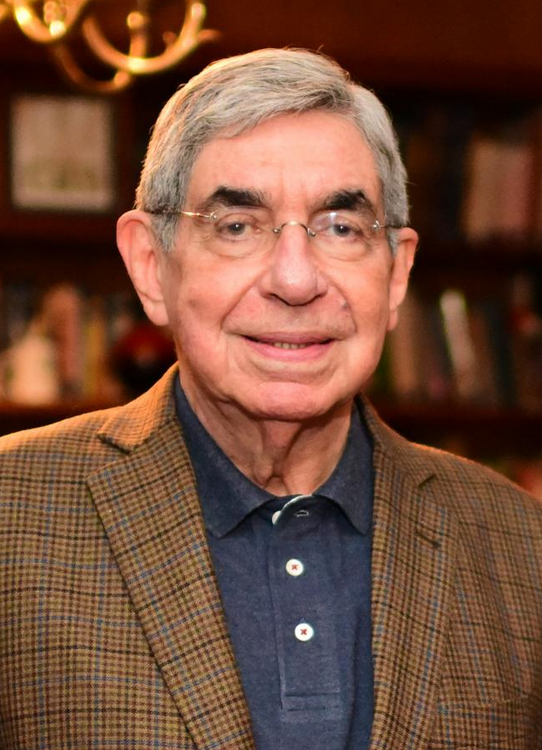

Óscar Arias *

2006–2010

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1647002

Carlos Alvarado Quesada *

2018–2022

By Dominik Butzmann / re:publica - Future Affairs Berlin 2019 - „Digital Revolution: Resetting Global Power Politics?“, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79440856

Leonel Fernández *

2004–2012

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1371874

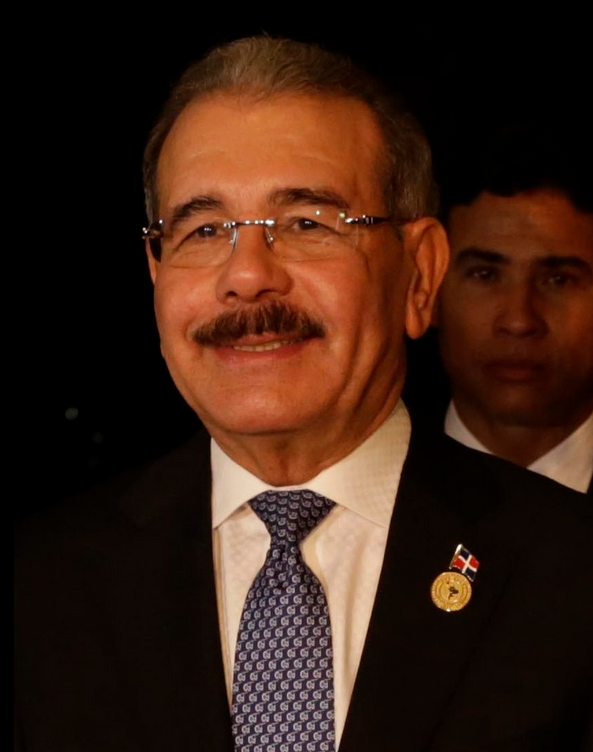

Danilo Medina *

2012–2020

By Presidencia El Salvador from San Salvador, El Salvador, América Central - V Cumbre CELAC- República Dominicana, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67121804

Luis Abinader *

2020–present

By Raquel Arbaje - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116874856

Gabriel Serville

2021–present

By Jean-Luc Hauser - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107056616

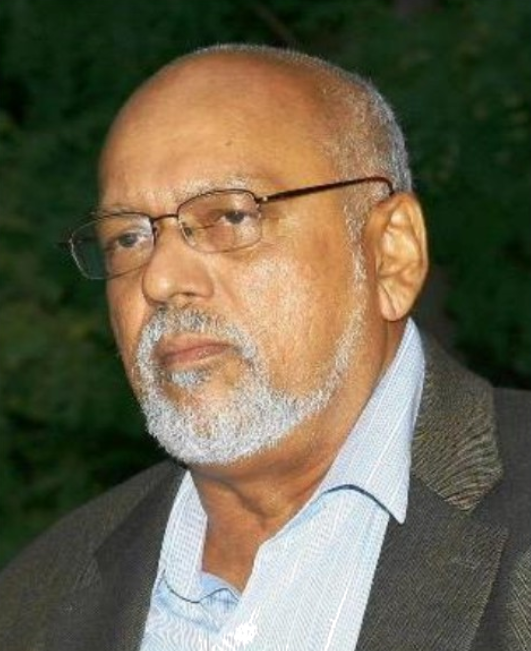

Bharrat Jagdeo

1999–2011

By Carl Lender - https://www.flickr.com/photos/clender/34327222001/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=97147397

Donald Ramotar

2011–2015

By Government Information Agency Guyana (GINA) - Government Information Agency Guyana (GINA), Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17647577

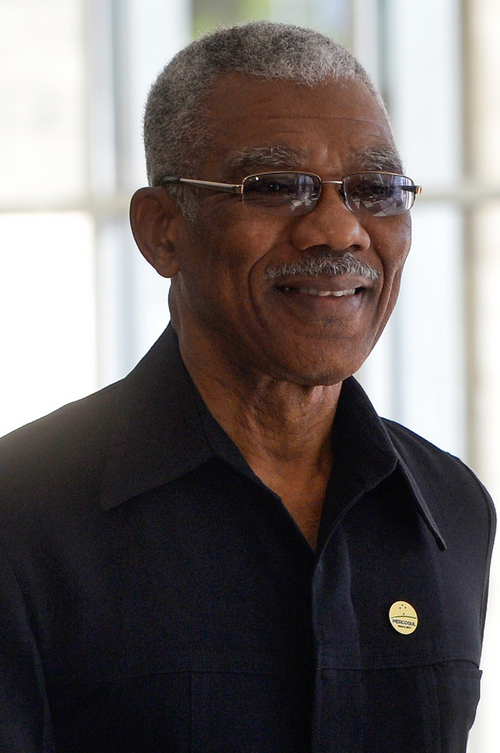

David Granger *

2015–2020

By Wilsom Dias/Agência Brasil - https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/politica/foto/2015-07/48a-cupula-do-mercosul-e-estados-associados, CC BY 3.0 br, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102444332

Irfaan Ali

2020–present

By U.S. Department of State from United States - Secretary Pompeo Holds a Joint Press Availability with Guyanese President Ali, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=94306192

Haiti

Jean-Bertrand Aristide

2001–2004

https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2097606

Kenny Anthony

2011–2016

By National Police of Colombia - This image was sourced from the Flickr gallery of the National Police of Colombia., CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99567177

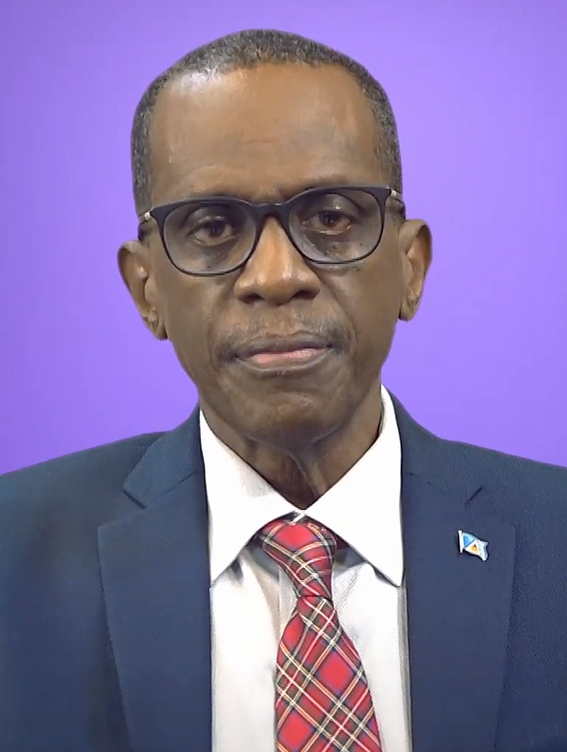

Philip J. Pierre

2021–present

By Saint Lucia Government, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107914437

Ralph Gonsalves

2001–present

By 總統府 - 10.11 總統與聖文森國總理龔薩福(Ralph E. Gonsalves)互贈禮物, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84906081

Dési Bouterse

2010–2020

By Cabinet of the President of the Republic of Suriname - president.gov.sr, Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=106140620

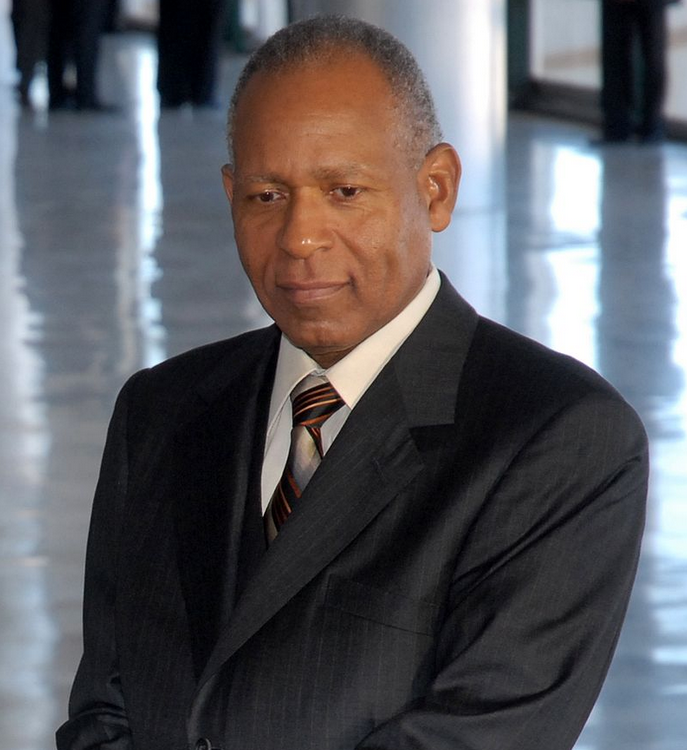

Patrick Manning *

2001–2010

By Antonio Cruz - Crop of Agência Brasil photograph http://www.agenciabrasil.gov.br/media/imagens/2008/07/23/1355AC00037.jpg/view, CC BY 3.0 br, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4472581

Kamla Persad-Bissessar *

2010–2015

By Control Arms - https://www.flickr.com/photos/controlarms/9936466353/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32085372

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Social:Pink_tide

References

- McSherry, J. Patrice (2011). "Chapter 5: "Industrial repression" and Operation Condor in Latin America". State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0415664578. https://www.routledge.com/State-Violence-and-Genocide-in-Latin-America-The-Cold-War-Years/Esparza-Huttenbach-Feierstein/p/book/9780415496377.

- "Los secretos de la guerra sucia continental de la dictadura" (The secrets of the continental dirty war of the dictators), Clarin, 24 March 2006 (in Spanish). http://www.clarin.com/suplementos/especiales/2006/03/24/l-01164353.htm

- Walter L. Hixson (2009). The Myth of American Diplomacy: National Identity and U.S. Foreign Policy. Yale University Press. p. 223. ISBN:0300151314. http://yalepress.yale.edu/book.asp?isbn=9780300119121

- Greg Grandin (2011). The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN:978-0226306902. https://books.google.com/books?id=6FivSpNY2fkC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA75#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Society, National Geographic (17 December 2013). "Archives of Terror Discovered". http://www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/dec22/archives-terror-discovered/.

- Klein, Naomi (2007). The Shock Doctrine. New York: Picador. p. 126. ISBN 978-0312427993. https://books.google.com/books?id=PwHUAq5LPOQC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA126#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Stanley, Ruth (2006). "Predatory States. Operation Condor and Covert War in Latin America/When States Kill. Latin America, the U.S., and Technologies of Terror". Journal of Third World Studies. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3821/is_200610/ai_n17195860.

- "Massacres, disappearances and 1968: Mexicans remember the victims of a 'perfect dictatorship'". The Conversation. 5 October 2008. https://theconversation.com/massacres-disappearances-and-1968-mexicans-remember-the-victims-of-a-perfect-dictatorship-104196.

- Ruiz, Bert (December 2012). The Colombian Civil War. ISBN 9780786450725. https://books.google.com/books?id=VIhTBasaETAC&dq=united+states+colombia+rojas+pinilla+dulles&pg=PA104.

- "CIA acknowledges involvement in Allende's overthrow, Pinochet's rise". BBC News. 19 September 2000. http://archives.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/americas/09/19/us.cia.chile.ap/.

- "World Publics Reject US Role as the World Leader". The Chicago Council on Public Affairs. April 2007. http://www.worldpublicopinion.org/pipa/pdf/apr07/CCGA+_ViewsUS_article.pdf.

- "Argentina: Opinion of the United States". Pew Research Center. 2012. http://www.pewglobal.org/database/?indicator=1&country=11.

- "Argentina: Opinion of Americans (Unfavorable) – Indicators Database". Pewglobal.org. http://www.pewglobal.org/database/indicator/2/country/11/response/Unfavorable/.

- Levitsky, Steven; Roberts, Kenneth. "The Resurgence of the Latin American Left" (PDF). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/394272/mod_resource/content/1/The%20Resurgence%20of%20the%20Latin%20Ame%20-%20Steven%20Levitsky%20Intro.pdf

- Levitsky, Ibid.

- Rodriguez, Robert G. (2014). "Re-Assessing the Rise of the Latin American Left" (PDF). The Midsouth Political Science Review. Arkansas Political Science Association. 15 (1): 59. ISSN 2330-6882.

- Rojas, René (Summer 2018). "The Latin American Left's Shifting Tides". Catalyst 2 (2): 6–71. https://catalyst-journal.com/vol2/no2/the-latin-american-lefts-shifting-tides. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Levitsky, Ibid.

- McMaken, Ryan (2016). Latin America's Pink Tide Crashes On The Rocks. Mises Institute.

- Noel, Andrea (29 December 2015). "The Year the 'Pink Tide' Turned: Latin America in 2015". Vice News. https://news.vice.com/article/the-year-the-pink-tide-turned-latin-america-in-2015.

- Miroff, Nick (28 January 2014). "Latin America's political right in decline as leftist governments move to middle". https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/28/colombia-latin-america-political-shift.

- Reid, Michael (September–October 2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs 94 (5): 45–53. "... half a dozen countries, led by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, formed a hard-left anti-American bloc with authoritarian tendencies...".

- Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (Jan–Apr 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro) 38 (1): 11–53. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100001. "The fate of Latin America's left turn has been closely associated with the commodities boom (or supercycle) of the 2000s, largely due to rising demand from emerging markets, notably China.". https://dx.doi.org/10.1590%2FS0102-8529.2016380100001

- Lansberg-Rodríguez, Daniel (Fall 2016). "Life after Populism? Reforms in the Wake of the Receding Pink Tide". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs (Georgetown University Press) 17 (2): 56–65. doi:10.1353/gia.2016.0025. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353%2Fgia.2016.0025

- Fisher, Max; Taub, Amanda (1 April 2017). "How Does Populism Turn Authoritarian? Venezuela Is a Case in Point". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/01/world/americas/venezuela-populism-authoritarianism.html.

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs 94 (5): 45–53. "As China industrialized in the first decade of the century, its demand for raw materials rose, pushing up the prices of South American minerals, fuels, and oilseeds. From 2000 to 2013, Chinese trade with Latin America rocketed from $12 billion to over $275 billion. ... Its loans have helped sustain leftist governments pursuing otherwise unsustainable policies in Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela, whose leaders welcomed Chinese aid as an alternative to the strict conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund or the financial markets. ... The Chinese-fueled commodity boom, which ended only recently, lifted Latin America to new heights. The region – and especially South America – enjoyed faster economic growth, a steep fall in poverty, a decline in extreme income inequality, and a swelling of the middle class.".

- "Americas Economy: Is the "Pink Tide" Turning?". The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. 8 December 2015. "In 2004-13 many pink tide countries benefited from strong economic growth, with exceptionally high commodities prices driving exports, owing to robust demand from China. These conditions brought regional growth ... However, the negative impact of expansionary policy on inflation, fiscal deficits and non-commodity exports in many countries soon began to prove that this boom period was unsustainable, even before international oil prices plummeted alongside prices of other key commodities at the end of 2014. ... These challenging economic conditions have exposed the negative consequences of years of policy mismanagement in various countries, most notably in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela.".

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues (Brookings Institution): 5–6. "[China] promised to impose no political conditions on its economic and technical assistance, in contrast to the usual strings-attached approach from Washington, Europe, and the international financial institutions, and committed to debt cancellation 'as China's ability permits.' ... As one South American diplomat put it, given the choice between the onerous conditions of the neoliberal Washington consensus and the no-strings-attached largesse of the Chinese, elevating relations with Beijing was a no-brainer.".

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues (Brookings Institution): 11–12. "Countries that are part of the so-called "pink tide" in Latin America, most notably Venezuela, have tended to defy international sanctions and partner with Iran. Venezuela's economic ties to Iran reportedly have helped Tehran to skirt international sanctions through the establishment of joint companies and nancial entities. Other ALBA countries such as Ecuador and Bolivia have also been important strategic partners to Iran, allowing the regime to extract uranium needed for its nuclear program.".

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs 94 (5): 45–53. "Washington's trade strategy was to contain Chávez and his dreams of continental domination ... the accurate assessment that Chávez was a threat to his own people. ... Chávez's regional influence peaked around 2007. His regime lost appeal because of its mounting authoritarianism and economic difficulties.".

- "The ebbing of the pink tide". The Economist. https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21679192-mauricio-macris-remarkable-victory-will-reverberate-across-south-america-ebbing-pink.

- Long, Gideon (29 December 2017). "Lenín Moreno unpicks Ecuador's leftwing legacy". https://www.ft.com/content/aa2c331a-e265-11e7-97e2-916d4fbac0da.

- de Oliveira Neto, Claire; Howat Berger, Joshua (1 September 2016). "Latin America's 'pink tide' ebbs to new low in Brazil". Agence France-Presse. https://www.yahoo.com/news/latin-americas-pink-tide-ebbs-low-brazil-102115760.html.

- "The Left on the Run in Latin America". The New York Times. 23 May 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/23/opinion/the-left-on-the-run-in-latin-america.html?_r=0.

- Lopes, Arthur (Spring 2016). "¿Viva la Contrarrevolución? South America's Left Begins to Wave Goodbye". Harvard International Review 37 (3): 12–14. "South America, a historical bastion of populism, has always had a penchant for the left, but the continent's predilection for unsustainable welfarism might be approaching a dramatic end. ... This 'pink tide' also included the rise of populist ideologies in some of these countries, such as Kirchnerismo in Argentina, Chavismo in Venezuela, and Lulopetismo in Brazil.".

- "Resurgence of the 'Pink Tide'? Revisiting Left Politics in Latin America". EPW Engage. 23 December 2019. https://www.epw.in/engage/article/resurgence-pink-tide-revisiting-left-politics.

- "Uribe reconoce derrota del Centro Democrático en las regionales". El Tiempo. 27 October 2019. https://www.eltiempo.com/politica/partidos-politicos/expresidente-uribe-reconoce-derrota-en-las-elecciones-regionales-427716.

- Cuttin, Maurizio. "The Americas: Is the 'Pink tide' seeing a resurgence?". https://warwickcongress.com/2019/11/29/the-americas-is-the-pink-tide-seeing-a-resurgence/.

- "Luis Arce promises to 'rebuild' Bolivia after huge election win". Al Jazeera. 23 October 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/10/23/final-count-gives-big-victory-for-luis-arce-in-bolivia-election.

- Ramos, Daniel (24 October 2020). "Bolivia's Arce pledges to "rebuild" as landslide election win confirmed". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/bolivia-election-idUSKBN27902N.

- Allen, Nicolas (10 June 2021), "Left-Wing Trade Unionist Pedro Castillo Will Be President of Peru", Jacobin, https://jacobinmag.com/2021/06/pedro-castillo-president-peru-libre, retrieved 21 July 2021

- Arsenault, Chris (2021-12-14). "How left-wing forces are regaining ground in Latin America". Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/12/14/how-left-wing-forces-are-regaining-ground-in-latin-america.

- Luna, Patricia; Goodman, Joshua (2021-12-19). "Leftist millennial wins election as Chile's next president". Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/elections-caribbean-donald-trump-chile-santiago-5fc78a1fe1cb26a06839e8a7b59c8730.

- Carlsen, Laura; Dickinson, Elizabeth; Dimitroff, Sashe; Guzmán, Sergio; Molina, Marco; Shifter, Michael; Velez de Berliner, Maria (21 June 2022). "What Will Petro's Presidency Mean for Colombia?". Inter-American Dialogue. https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/what-will-petros-presidency-mean-for-colombia/.

- Turkewitz, Julie (2022-06-19). "Colombia Election: Gustavo Petro Makes History in Presidential Victory". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/06/19/world/colombia-election-results.

- Galindo, Jorge (20 June 2022). "How Colombia shifted to the left". El País. https://english.elpais.com/international/2022-06-20/how-colombia-shifted-to-the-left.html.

- Prashad, Vijay (6 December 2019). "Latin America: Return of the Pink Tide". https://frontline.thehindu.com/world-affairs/article30025582.ece.

- "Introduction: Lula's Legacy in Brazil". NACLA. https://nacla.org/article/introduction-lula's-legacy-brazil.

- Kingstone, Steve (2010). "How President Lula changed Brazil". BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-11458409.

- Phillips, Don (17 October 2017). "Accused of corruption, popularity near zero – why is Temer still Brazil's president?". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/17/accused-of-graft-popularity-near-zero-so-why-is-brazils-president-still-in-office.

- Edo, María; Marchionni, Mariana; Garganta, Santiago (November 2015). "Conditional Cash Transfer Programs and Enforcement of Compulsory Education Laws. The case of Asignación Universal por Hijo in Argentina". Center for Distributive, Labor and Social Studies Working Papers (Center for Distributive, Labor and Social Studies) (190). ISSN 1853-0168. https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/wp-content/uploads/doc_cedlas190.pdf. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Evo Morales". https://www.britannica.com/biography/Evo-Morales.

- Schipani, Andres (11 February 2010). "Bolivian women spearhead Morales revolution". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8498081.stm.

- Tegel, Simeon (17 July 2016). "A surprising move on LGBT rights from a 'macho' South American president". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/07/17/a-surprising-move-on-lgbt-rights-from-a-macho-south-american-president/.

- North, James (4 June 2015). "Why Ecuador's Rafael Correa Is One of Latin America's Most Popular Leaders". The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/why-ecuadors-rafael-correa-one-latin-americas-most-popular-leaders/.

- Miroff, Nick (15 March 2014). "Ecuador's popular, powerful president Rafael Correa is a study in contradictions". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/ecuadors-popular-powerful-president-rafael-correa-is-a-study-in-contradictions/2014/03/15/452111fc-3eaa-401b-b2c8-cc4e85fccb40_story.html.

- "Paraguay" (PDF). http://www.rabobank.com/content/images/Paraguay-201101_tcm43-105909.pdf

- "Paraguay: Mixed Results for Lugo's First 100 Days". Inter Press Service. 25 November 2008. http://www.ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=44857.

- "Chap 10". https://archive.today/20130414110612/http://www.bti-project.org/countryreports/lac/pry/2012/%23chap10

- "The boy and the bishop". The Economist. 30 April 2009. http://www.economist.com/node/13579202?story_id=13579202.

- "The Bishop of the Poor: Paraguay's New President Fernando Lugo Ends 62 Years of Conservative Rule". http://www.democracynow.org/2008/8/19/inauguration_of_paraguays_new_president_fernando.

- Fernandes Pimenta, Gabriel; Casas V M Arantes, Pedro (2014). "Rethinking Integration in Latin America: The "Pink Tide" and the Post-Neoliberal Regionalism". FLACSO. http://web.isanet.org/Web/Conferences/FLACSO-ISA%20BuenosAires%202014/Archive/19e10599-bf80-42fa-a9e1-accb107de234.pdf. Retrieved 28 December 2017. "In general, one must say that these governments have as defining common feature ample and generous social inclusion policies that link effectively for social investments that certainly had an impact on regional social indicators (LIMA apud SILVA, 2010a). In this sense, so far, all of these countries had positive improvements. As a result, it was observed the reduction in social inequality, as well as the reduction of poverty and other social problems (SILVA, 2010a)".

- Abbott, Jared. Will the Pink Tide Lift All Boats? Latin American Socialisms and Their Discontents. http://www.dsausa.org/will_the_pink_tide_lift_all_boats. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "Tres tenues luces de esperanza Las fuerzas de izquierda cobran impulso en tres países centroamericanos". Nueva Sociedad. 2014. http://www.nuso.org/upload/articulos/PERSPECTIVA%20Koschuetzke%20Lanz.pdf.

- Ystanes, Margit; Åsedotter Strønen, Iselin (25 October 2017). The Social Life of Economic Inequalities in Contemporary Latin America. ISBN 978-3319615363. https://books.google.com/books?id=RaI7DwAAQBAJ. "[reduction of inequality gap] On average, the decrease was much slower for countries not under the Pink Tide governments (Cornia 2012). In light of this, it is clear that the Pink Tide governments positively impacted the living standards of the working classes."

- OECD. "Costa Rica – Economic forecast summary (November 2016)". http://www.oecd.org/eco/outlook/costa-rica-economic-forecast-summary.htm.

- "Boom económico en Ecuador". El Telégrafo. http://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/columnistas/1/boom-economico-en-ecuador.

- "Ecuador". World Bank. 2014. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ecuador/overview.

- "Nicaragua". World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nicaragua/overview.

- "Reducing poverty in Bolivia comes down to two words: rural development". World Bank. 2015. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/07/06/desarrollo-rural-para-reducir-pobreza-bolivia.

- "El Salvador". World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/elsalvador/overview.

- Partlow, Joshua; Caselli, Irene (23 November 2015). "Does Argentina's pro-business vote mean the Latin American left is dead?". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/does-argentinas-pro-business-vote-mean-the-latin-american-left-is-dead/2015/11/23/acb85f04-915a-11e5-befa-99ceebcbb272_story.html.

- "Why the United States and Cuba are cosying up". The Economist. 29 May 2015. https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2015/05/economist-explains-37.

- Usborne, David (4 December 2015). "Venezuela's ruling socialists face defeat at polls". The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/venezuela-s-ruling-socialists-face-defeat-at-polls-amid-unrest-and-chaos-a6761261.html.

- Eulich, Whitney (4 April 2017). "Even as South America tilts right, a leftist legacy stands strong". Christian Science Monitor. http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Americas/2017/0404/Even-as-South-America-tilts-right-a-leftist-legacy-stands-strong.

- Isbester, Katherine (2011). The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1442601802.

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs 94: 45–53. "Officials in the Obama administration argued that it was counterproductive to publicly criticize Chávez, since doing so failed to change his behavior and merely allowed him to pose as a popular campaigner against American imperialism ... According to Latinobarómetro, a polling organization, an average of 69 percent of respondents in the region held a favorable view of the United States in 2013, up from 58 percent in 2008. ... In today's Latin America, it is hard to imagine that more confrontational policies would have achieved better results, ... the United States is no longer the only game in town in much of Latin America, bullying is often ineffective. ... circumstances in the region are becoming increasingly favorable for the United States.".

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues (Brookings Institution): 7–8. "Meanwhile, recent public opinion polls of Latin Americans reveal wavering attitudes toward China's influence in the region ... opinions of China as a model and as a rising power declined between 2012 and 2014. ... the authors concluded that negative views of China were widespread, mainly regarding the poor quality of Chinese goods, unfair business practices, incompatible language and culture, unsustainable development policies harmful to the environment, and fears of Chinese economic and demographic domination in international relations.".

- "Latin America's 'pragmatic' pink tide". Pittsburgh Tribune-Herald. 16 May 2016. http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/s_310062.html.

- Carlsen, Laura (15 December 2006). "Latin America's Pink Tide?". Institute for Policy Studies. http://www.fpif.org/fpiftxt/3806.

- "The Issue: A Changing Latin America: Fears of 'Pink Tide'". The Arizona Republic. 12 June 2006.

- "Challenges 2006–2007: A Bad Year for Empire". . Inter Press Service. http://www.ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=35951

- "Tres tenues luces de esperanza Las fuerzas de izquierda cobran impulso en tres países centroamericanos". Nueva Sociedad. 2014. http://www.nuso.org/upload/articulos/PERSPECTIVA%20Koschuetzke%20Lanz.pdf.

- Angelo, Paul J.; Freeman, Will (23 June 2021). "A Socially Conservative Left Is Gaining Traction in Latin America". https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/a-socially-conservative-left-is-gaining-traction-in-latin-america/.

- "Is there a new Pink Tide on Latin America's horizon?". The Perspective. 9 March 2021. https://www.theperspective.se/is-there-a-new-pink-tide-on-latin-americas-horizon/.

- Waddell, Benjamin (15 May 2019). "Why a generation of Latin American leaders failed to deliver on their promise of progress". The Week. https://theweek.com/articles/840587/why-generation-latin-american-leaders-failed-deliver-promise-progress.

- Silva, Fabricio Pereira da (2014). "Quinze anos da onda rosa latino-americana: balanço e perspectivas". Observador On-Line (Observatório Político Sul-Americano) 9 (12). ISSN 1809-7588. https://www.academia.edu/24574677. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- Rivera, Ana (1 November 2019). "A Faded Pink Tide? Broad Peronist Coalition Defeats Macri in Argentina". Left Voice. https://www.leftvoice.org/a-faded-pink-tide-broad-peronist-coalition-defeats-macri-in-argentina.

- Gazzola, por Ana Elisa Thomazella. ""O declínio da "onda rosa" e os rumos da América Latina.". Observatório de Regionalismo. http://observatorio.repri.org/2018/06/04/o-declinio-da-onda-rosa-e-os-rumos-da-america-latina/.

- "The battle for Latin America: How the US helped destroy the "pink tide"". https://www.bilaterals.org/?the-battle-for-latin-america-how.

- Gibson, Carrie (9 January 2021). "¡Populista! review: Chávez, Castro and Latin America's 'pink wave' leaders". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jan/09/populista-review-chavez-castro-latin-america-pink-wave-strongmen.

- Prevost, G.; Vanden, H.; Campos, C.; Ayerbe, Luis Fernando (20 March 2014). US National Security Concerns in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Concept of Ungoverned Spaces and Failed States. ISBN 9781137379528. https://books.google.com/books?id=xX6EAwAAQBAJ&dq=centrist+martin+torrijos&pg=PT80.

- "Panama election: Cortizo wins unexpectedly close race". BBC News. 6 May 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-48174497.

- "'Panama decided its future': Cortizo is declared winner". https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/5/6/panama-elections-centrist-laurentino-cortizo-declared-winner.

- Keating, Joshua (23 April 2009). "Paraguay's baby-daddy in chief". Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/04/23/paraguays-baby-daddy-in-chief/.

- Mahler, Anne Garland (19 April 2018). From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity. ISBN 9780822371717. https://books.google.com/books?id=uyZWDwAAQBAJ&q=fernando&pg=PT210.

- Book: Ollanta Humala: de Locumba a candidato a la presidencia en Perú

- Crabtree, John (25 March 2012). "The new Andean politics: Bolivia. Peru, Ecuador". openDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/new-andean-politics-bolivia-peru-ecuador/.

- Santos, Leandro Wolpert dos (2020). "Capítulo 8: Política externa do Peru em um contexto regional em transformação (2006-2018) – da onda rosa à guinada à direita". in Lima, Maria Regina Soares de. América do Sul no século XXI: desafios de um projeto político regional. Rio de Janeiro: Multifoco. pp. 139–155. ISBN 978-65-5611-032-5. http://opsa.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Am%C3%A9rica-do-Sul-no-s%C3%A9culo-XXI-Desafios-de-um-projeto-pol%C3%ADtico-regional.pdf#page=139.

- Garat, Guillermo. "Tabaré Vázquez, Uruguay's first socialist president, dies at 80". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/tabare-vazquez-dead/2020/12/06/8c56f6c4-3828-11eb-9276-ae0ca72729be_story.html.

- Pribble, Jennifer (28 Oct 2019). "Chile's crisis was decades in the making". Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/81801886-f650-11e9-bbe1-4db3476c5ff0.

- Renaud, Lambert (2010-03-01). "A onda rosa". Renaud Lambert (Le Monde Diplomatique). https://diplomatique.org.br/a-onda-rosa/. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- "A onda rosa - le Monde Diplomatique". https://diplomatique.org.br/a-onda-rosa/.

- SCHEPERS, EMILE (June 3, 2016). "The Bolivarian crisis: Is Latin America's "pink tide" receding?". https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/the-bolivarian-crisis-is-latin-america-s-pink-tide-receding/.

- Becker,Marc. Twentieth-Century Latin American Revolutions.

- Fernandes Pimenta, Gabriel; Casas V M Arantes, Pedro (July 23–25, 2014). Rethinking Integration in Latin America: The "Pink Tide" and the PostNeoliberal Regionalism. FLACSO-ISA Joint International Conference Buenos Aires, Argentina. http://web.isanet.org/Web/Conferences/FLACSO-ISA%20BuenosAires%202014/Archive/19e10599-bf80-42fa-a9e1-accb107de234.pdf. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- Jeremy Prestholdt (1 July 2019). Icons of Dissent: The Global Resonance of Che, Marley, Tupac and Bin Laden. Oxford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-19-009264-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=mXKfDwAAQBAJ&q=dési+bouterse+pink+tide&pg=PA206.

- https://www.ibiconsultants.net/_pdf/cuba-in-the-bolivarian-revolution.pdf

- "A decade of reporting by the FT's outgoing Latin America editor". Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/0ef20fb0-680a-11e9-9adc-98bf1d35a056.