An emissions budget, carbon budget, emissions quota, or allowable emissions, is an upper limit of total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with remaining below a specific global average temperature. An emissions budget may also be associated with objectives for other related climate variables, such as radiative forcing. Global emissions budgets are calculated according to historical cumulative emissions from fossil fuel combustion, industrial processes, and land-use change, but vary according to the global temperature target that is chosen, the probability of staying below that target, and the emission of other non-CO2 greenhouse gases (GHGs). Global emissions budgets can be further divided into national emissions budgets, so that countries can set specific climate mitigation goals. Emissions budgets are relevant to climate change mitigation because they indicate a finite amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted over time, before resulting in dangerous levels of global warming. Change in global temperature is independent from the geographic location of these emissions, and is largely independent of the timing of these emissions. In line with the 2018 Special report on Global Warming of 1.5° C by the IPCC, the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change estimates that the CO2 budget associated with 1.5 °C degrees of warming will be exhausted in 2028 if emissions remain on the current level of the late 2010s. Beyond a 1.5°C temperature rise, the risk of long-lasting and irreversible consequences of climate change increases. An emissions budget may be distinguished from an emissions target, as an emissions target may be internationally or nationally set in accordance with objectives other than a specific global temperature. This includes targets created for their political palatability, rather than ones focused on climate science warnings.

- climate science

- climate change

- climate mitigation

1. Estimations

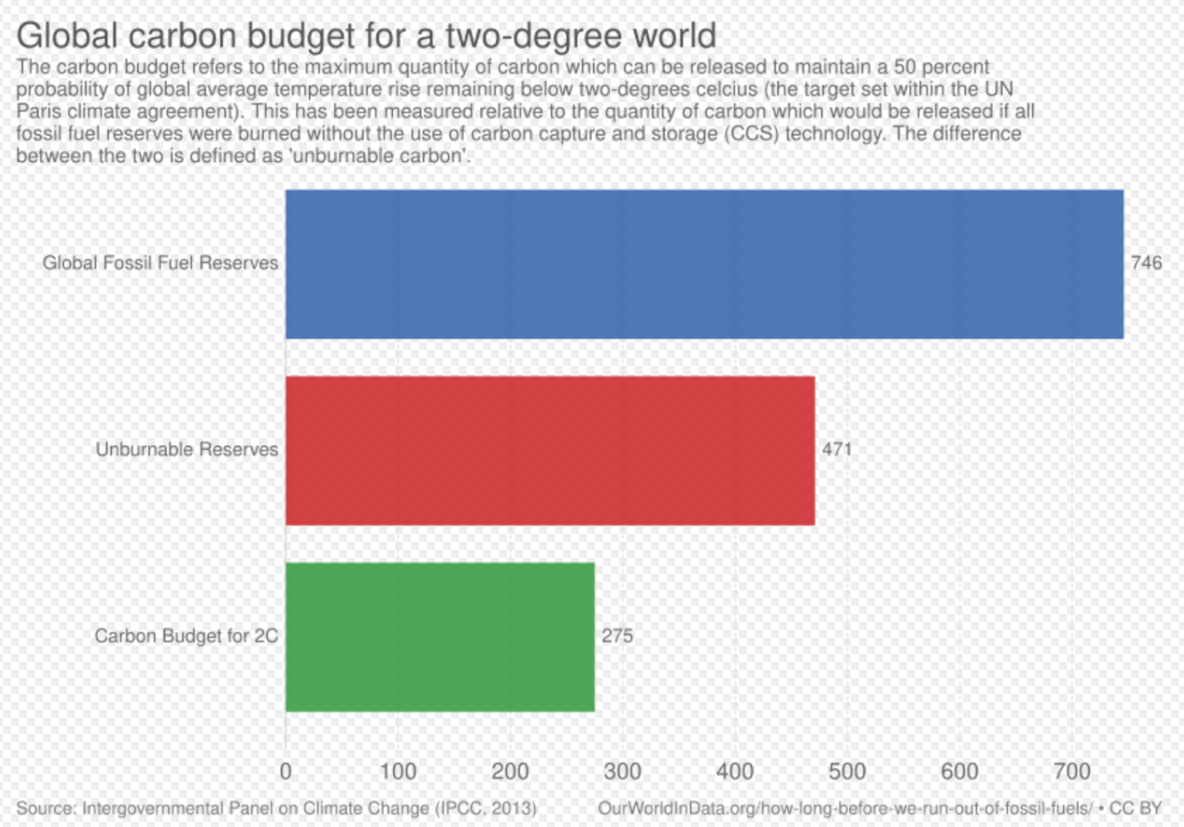

The finding of an almost linear relationship between global temperature rise and cumulative carbon dioxide emissions[1] has encouraged the estimation of global emissions budgets in order to remain below dangerous levels of warming. Since the pre-industrial period to 2011, approximately 1890 Gigatonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) has already been emitted globally, and 2050 GtCO2 up to 2015.[2]

Scientific estimations of the remaining global emissions budgets/quotas differ widely due to varied methodological approaches, and considerations of thresholds.[2] Most estimations still underestimate the amplifying climate change feedbacks.[3][4][5][6]

Some common budget estimations are those associated with a 1.5 °C[7][8][9] and 2 °C global warming.[10][11][12] These estimates depend highly on the likelihood or probability of reaching a temperature target. The values for the budget exhausted in the following table have been derived from a scenario in which CO

2 emissions remain on the current level of 42 Gt per year.

| Target for average

global temperature rise |

budget exhausted in | Likelihood

of staying below target |

budget Gt of CO 2 |

Date range | Source (Rogelj et al. 2016 has another list of estimates[2]) | Page in source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 °C = 2.7 °F | 2034-2037 | 66% | 810-920 | 2015-2100 | Millar et al. 2017[7] | 4 |

| 1.5 °C = 2.7 °F | 2020-2025 | 50% | 400-570 | 2011-2100 | Rogelj et al. 2015[9] | 3 |

| 1.5 °C = 2.7 °F | 2047 | 50% | 1400 | 2015-2100 | Millar et al. 2017[7] | 4 |

| 1.5 °C = 2.7 °F | 2041 | 50% | 1060 | 2016-2100 | Matthews et al. 2015[8] | subtraction in Table 2 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2025-2031 | 75% | 610-830 | 2011-2100 | Rogelj et al. 2015 | 3 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2034 | 66% | 1200 | 2015-2100 | Friedlingstein et al. 2014[11] | 710 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2044 | 66% | 1000 | 2020-2100 | Friedlingstein et al. 2014 | 710 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2035 | 66% | 990 | 2012-2100 | 2015 IPCC 2015[13] | 1113 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2033 | 66% | 940 | 2011-2100 | Rogelj et al. 2015 | 3 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2035-2045 | 50% | 990-1450 | 2011-2100 | Rogelj et al. 2015 | 3 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2066 | 50% | 2085 | 2016-2100 | Matthews et al. 2015 | subtraction in Table 2 |

| 2 °C = 3.6 °F | 2051 | 50% | 1500 | 2015-2100 | Friedlingstein et al. 2014 | 710 |

| 3 °C = 5.4 °F | 2084 | 66% | 2900 | 2015-2100 | Friedlingstein et al. 2014 | 710 |

| 3 °C = 5.4 °F | 2094 | 50% | 3300 | 2015-2100 | Friedlingstein et al. 2014 | 710 |

1 GtC (carbon) = 3.67 GtCO2 [14]

Alternative to budgets set explicitly using temperature objectives, emissions budgets have also been estimated using the Representative Concentration Pathways, which are based on radiative forcing values at the end of the century.[15] (Although temperatures may be inferred from radiative forcing). These were presented in the International Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment report.[16] According to the World Meteorological Organization there is a 20% chance that in the years 2020 - 2024 at least in one year the average temperature will be higher than 1.5°C above preindustrial level.[17]

2. Carbon Capture

Researchers expect emissions will exceed any of these remaining budgets. In order to comply with the budget limits, they expect CO

2 will need to be captured from the atmosphere and stored in products, the environment or underground. A 2015 study in Nature says carbon budgets can only be met by capturing CO

2, "in all but the most optimistic cases, we also find negative emission requirements that have not yet been shown to be achievable"[18]

Scientists widely agree this research is needed. IPCC says, "All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C [2.7°F] with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100-1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak (high confidence)."[19]

Even for the less strict goal of 2 °C [3.6 °F] warming, carbon capture is needed. IPCC has only one scenario (they call it a "Representative Concentration Pathway" RCP) which limits warming to 3.6 °F: "RCP2.6 is representative of a scenario that aims to keep global warming likely below 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures. The majority of models indicate that scenarios meeting forcing levels similar to RCP2.6 are characterized by substantial net negative emissions by 2100, on average around 2 GtCO2/yr."[13]:57

3. National Emissions Budgets

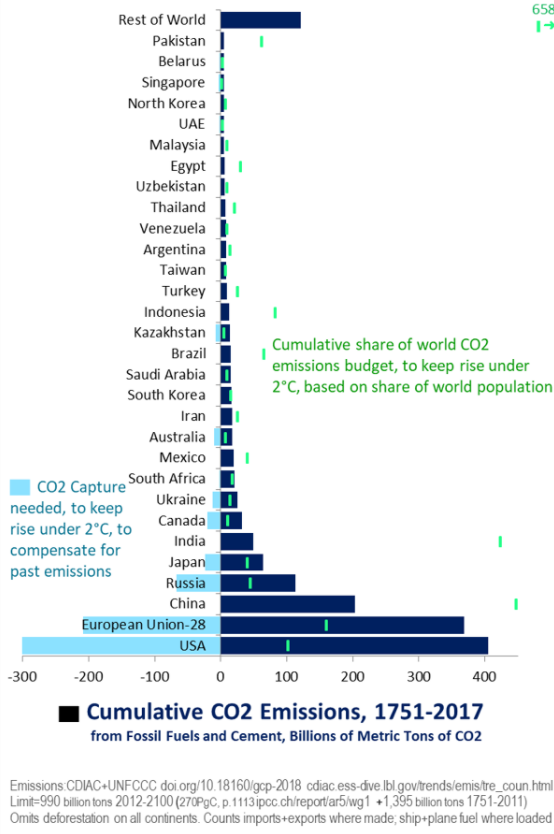

In light of the many differences between nations, including but not limited to population, level of industrialization, national emissions histories, and mitigation capabilities, scientists have made attempts to allocate global carbon budgets among countries using methods that follow various principles of equity.[20] Allocating national emissions budgets is comparable to sharing the effort to reduce global emissions, underlined by some assumptions of state-level responsibility of climate change. Many authors have conducted quantitative analyses which allocate emissions budgets,[21][22][23][24] often simultaneously addressing disparities in historical GHG emissions between nations. National 'Paris-compliant' emissions budgets have also been calculated that quantify the discrepancy between the emissions reductions resulting from current national mitigation pathways and those needed to live up to the temperature and equity commitments enshrined in the Paris Agreement.[21]

One common principle that has been used to allocate global emissions budgets to nations is the "responsibility" or "polluter-pays" principle.[20] This principle recognizes nations' cumulative historical contributions to global emissions. So those countries with greater emissions during a set time period (for example, since the pre-industrial era to the present) would be most responsible for addressing excess emissions. Thus, their national emissions budgets would be smaller than those that have polluted less in the past. The concept of national historical responsibility for climate change has prevailed in the literature since the early 1990s.[25][26] Consequently, some have quantified cumulative historical emissions of states, to identify who has most responsibility to take the strongest actions.[27] This principle is often favoured by developing countries, as it gives them larger emissions budgets.[28]

Another common equity principle for calculating national emissions budgets is the "egalitarian" principle. This principle stipulates individuals should have equal rights to pollute, and therefore emissions budgets should be distributed proportionally according to state populations.[20] Some scientists have thus reasoned the use of national per-capita emissions in national emissions budget calculations.[22][23][29] This principle may be favoured by nations with larger or rapidly growing populations.[28]

A third equity principle that has been employed in national budget calculations considers national sovereignty.[20] The "sovereignty" principle highlights the equal right of nations to pollute.[20] The grandfathering method for calculating national emissions budgets uses this principle. Grandfathering allocates these budgets proportionally according to emissions at a particular base year,[29] and has been used under international regimes such as the Kyoto Protocol[30] and the early phase of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)[31] This principle is often favoured by developed countries, as it allocates larger emissions budgets to them.[28]

As per Bill Gates latest book entitled "How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need" the GHG (Green House Gases) emissions per sector of the economy are distributed as per the following chart available on blog http://www.whereintheworldismario.com/2021/05/innovate-to-zero-ghg-emissions.html

According to Gates, the hardest sector needing technical breakthroughs to decarbonize is also the largest GHG emitor: Industrial. Many are trying to reduce de price to zero emissions Cement and Steel aswell as looking for substitutes but not even close to what is needed to cut those emissions in 50% by 2030.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Earth:Emissions_budget

References

- Matthews, H. Damon; Gillett, Nathan P.; Stott, Peter A.; Zickfeld, Kirsten (June 2009). "The proportionality of global warming to cumulative carbon emissions". Nature 459 (7248): 829–832. doi:10.1038/nature08047. PMID 19516338. Bibcode: 2009Natur.459..829M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature08047

- Rogelj, Joeri; Schaeffer, Michiel; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Gillett, Nathan P.; van Vuuren, Detlef P.; Riahi, Keywan; Allen, Myles; Knutti, Reto (24 February 2016). "Differences between carbon budget estimates unravelled". Nature Climate Change 6 (3): 245–252. doi:10.1038/nclimate2868. Bibcode: 2016NatCC...6..245R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnclimate2868

- Rogelj, Joeri; Forster, Piers M.; Kriegler, Elmar; Smith, Christopher J.; Séférian, Roland (17 July 2019). "Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate targets". Nature 571 (7765): 335–342. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1368-z. PMID 31316194. Bibcode: 2019Natur.571..335R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fs41586-019-1368-z

- Jamieson, Naomi Oreskes,Michael Oppenheimer,Dale. "Scientists Have Been Underestimating the Pace of Climate Change" (in en). https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/scientists-have-been-underestimating-the-pace-of-climate-change/.

- Comyn-Platt, Edward (2018). "Carbon budgets for 1.5 and 2 °C targets lowered by natural wetland and permafrost feedbacks". Nature Geoscience 11 (8): 568–573. doi:10.1038/s41561-018-0174-9. Bibcode: 2018NatGe..11..568C. http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/77371/3/NaturalCH4_Permafrost_EmissionBudgets_FinalEdit.pdf.

- Lenton, Timothy M.; Rockström, Johan; Gaffney, Owen; Rahmstorf, Stefan; Richardson, Katherine; Steffen, Will; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim (2019-11-27). "Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against" (in en). Nature 575 (7784): 592–595. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0. PMID 31776487. Bibcode: 2019Natur.575..592L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fd41586-019-03595-0

- Millar, Richard J.; Fuglestvedt, Jan S.; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Rogelj, Joeri; Grubb, Michael J.; Matthews, H. Damon; Skeie, Ragnhild B.; Forster, Piers M. et al. (18 September 2017). "Emission budgets and pathways consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 °C". Nature Geoscience 10 (10): 741–747. doi:10.1038/ngeo3031. Bibcode: 2017NatGe..10..741M. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/120597/3/millaretal_natgeo_accepted.pdf.

- Matthews, H. Damon; Landry, Jean-Sébastien; Partanen, Antti-Ilari; Allen, Myles; Eby, Michael; Forster, Piers M.; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Zickfeld, Kirsten (27 February 2017). "Estimating Carbon Budgets for Ambitious Climate Targets". Current Climate Change Reports 3 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1007/s40641-017-0055-0. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/124351/1/Matthews_CarbonBudgets_accepted.pdf.

- Rogelj, Joeri; Reisinger, Andy; McCollum, David L; Knutti, Reto; Riahi, Keywan; Meinshausen, Malte (1 July 2015). "Mitigation choices impact carbon budget size compatible with low temperature goals". Environmental Research Letters 10 (7): 075003. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/7/075003. Bibcode: 2015ERL....10g5003R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F1748-9326%2F10%2F7%2F075003

- Meinshausen, Malte; Meinshausen, Nicolai; Hare, William; Raper, Sarah C. B.; Frieler, Katja; Knutti, Reto; Frame, David J.; Allen, Myles R. (April 2009). "Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to 2 °C". Nature 458 (7242): 1158–1162. doi:10.1038/nature08017. PMID 19407799. Bibcode: 2009Natur.458.1158M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature08017

- Friedlingstein, P.; Andrew, R. M.; Rogelj, J.; Peters, G. P.; Canadell, J. G.; Knutti, R.; Luderer, G.; Raupach, M. R. et al. (October 2014). "Persistent growth of CO 2 emissions and implications for reaching climate targets". Nature Geoscience 7 (10): 709–715. doi:10.1038/ngeo2248. Bibcode: 2014NatGe...7..709F. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fngeo2248

- Zickfeld, Kirsten; Eby, Michael; Matthews, H. Damon; Weaver, Andrew J. (22 September 2009). "Setting cumulative emissions targets to reduce the risk of dangerous climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (38): 16129–16134. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805800106. PMID 19706489. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2752604

- Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report https://ar5-syr.ipcc.ch/topic_futurechanges.php

- "Comparing CO2 emissions to CO2 levels". https://skepticalscience.com/print.php?r=45.

- van Vuuren, Detlef P.; Edmonds, James A.; Kainuma, Mikiko; Riahi, Keywan; Weyant, John (5 August 2011). "A special issue on the RCPs". Climatic Change 109 (1–2): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0157-y. Bibcode: 2011ClCh..109....1V. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10584-011-0157-y

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (2014). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05799-9. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/.

- Woodyatt, Amy (9 July 2020). "Global temperatures could exceed crucial 1.5 C target in the next five years". CNN. World Meteorological Organization. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/09/world/global-temperatures-wmo-climate-intl-scli/index.html.

- Gasser, T.; Guivarch, C.; Tachiiri, K.; Jones, C. D.; Ciais, P. (3 August 2015). "Negative emissions physically needed to keep global warming below 2 °C". Nature Communications 6 (1): 7958. doi:10.1038/ncomms8958. PMID 26237242. Bibcode: 2015NatCo...6.7958G. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fncomms8958

- 2018 IPCC p.19 "Global warming of 1.5°C Summary for Policymakers" https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/summary-for-policy-makers/

- Ringius, L.; Torvanger, A.; Underdal, A. (2002). "Burden sharing and fairness principles in international climate policy". International Environmental Agreements 2 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1023/a:1015041613785. https://folk.uio.no/stvau1/Journal%20articles/Burdensharing.pdf.

- Anderson, Kevin; Broderick, John F.; Stoddard, Isak (2020-05-28). "A factor of two: how the mitigation plans of 'climate progressive' nations fall far short of Paris-compliant pathways". Climate Policy 0 (10): 1290–1304. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1728209. ISSN 1469-3062. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F14693062.2020.1728209

- Baer, P.; Athanasiou, T.; Kartha, S.; Kemp-Benedict, E. (2009). "Greenhouse development rights: A proposal for a fair global climate treaty". Ethics Place and Environment 12 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1080/13668790903195495. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F13668790903195495

- Matthews, H. Damon (7 September 2015). "Quantifying historical carbon and climate debts among nations". Nature Climate Change 6 (1): 60–64. doi:10.1038/nclimate2774. Bibcode: 2016NatCC...6...60M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnclimate2774

- Raupach, Michael R.; Davis, Steven J.; Peters, Glen P.; Andrew, Robbie M.; Canadell, Josep G.; Ciais, Philippe; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Jotzo, Frank et al. (21 September 2014). "Sharing a quota on cumulative carbon emissions". Nature Climate Change 4 (10): 873–879. doi:10.1038/nclimate2384. Bibcode: 2014NatCC...4..873R. http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/1kv3p879.

- Grübler, A.; Fujii, Y. (1991). "Inter-generational and spatial equity issues of carbon accounts". Energy 16 (11–12): 1397–1416. doi:10.1016/0360-5442(91)90009-b. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/3489/1/RR-92-06.pdf.

- Smith, K. R. (1992). "Allocating responsibility for global warming: The natural debt index". Ambio. Stockholm 20 (2): 95–96.

- Botzen, W. J. W.; Gowdy, J. M.; Bergh, J. C. J. M. Van Den (1 January 2008). "Cumulative CO2 emissions: shifting international responsibilities for climate debt". Climate Policy 8 (6): 569–576. doi:10.3763/cpol.2008.0539. https://dx.doi.org/10.3763%2Fcpol.2008.0539

- Pan, J (2003). "Emissions rights and their transferability: equity concerns over climate change mitigation". International Environmental Agreements 3 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1023/A:1021366620577. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1021366620577

- Neumayer, Eric (2000). "In defence of historical accountability for greenhouse gas emissions". Ecological Economics 33 (2): 185–192. doi:10.1016/s0921-8009(00)00135-x. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/18906/1/__Libfile_repository_Content_Neumayer%2C%20E_In%20defense%20of%20historical%20accountability%20for%20greenhouse%20gas%20emissions_In%20defense%20of%20historical%20accountability%20for%20greenhouse%20gas%20emissions%20%28LSE%20RO%29.pdf.

- UNFCCC (1998). "Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change".(http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf)

- European Commission (2010) 2010/384/: Commission Decision of 9 July 2010 on the Community-wide quantity of allowances to be issued under the EU Emission Trading Scheme for 2013 (notified under document C(2010) 4658). Official Journal of the European Union L 175 36-37 (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32010D0384)