Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Flavonoids are a group of naturally occurring polyphenolic secondary metabolites which have been reported to demonstrate a wide range of pharmacological properties, most importantly, antidiabetic effects.

- flavonoids

- antidiabetic

- glycogen phosphorylase

1. Introduction

Flavonoids are a type of plant secondary metabolite with a polyphenolic structure, and they are one of the most common families of natural products (NPs). Flavonoids exist naturally as aglycones, glycosides, and methylated derivatives, which are abundant in fruits, vegetables, and some beverages. All flavonoids have fifteen carbon atoms in their fundamental nucleus C6–C3–C6 structure, with several chemical groups substituted. Flavonoids are categorized into chalcones, flavanones, flavanonols, flavones, flavanols, isoflavones, flavan-3-ols (catechins), and anthocyanidins based on their chemical structures, as illustrated in Figure 1. Flavonoids are a large family of NPs that have long been recognized as an essential component in a wide range of nutraceutical, pharmacological, medical, and cosmetic uses. They are also vital substances with various health-promoting advantages for various disorders, including anticancer, antioxidant, anti-infective, antitoxic, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and antiviral properties.

2. Antidiabetic Activity of Flavonoids

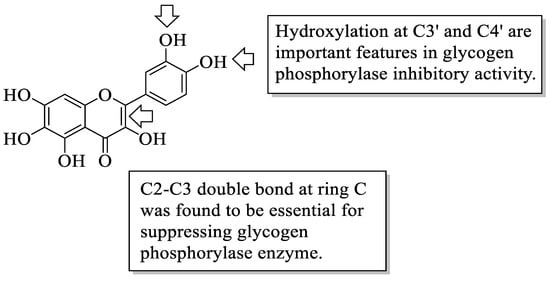

Flavonoids have been reported to demonstrate antidiabetic effects through various molecular mechanisms of action. Kato et al. investigated the structural requirements of flavonoids with glycogen phosphorylase inhibitory activity. Glycogen phosphorylase is one of the enzymes that catalyse the breakdown of glycogen into glucose in the liver, and its inhibition has been shown to modulate the glucose level associated with T2D [46]. The researchers discovered a flavone called quercetagetin (3,3′,4′,5,6,7-hexahydroxyflavone (44), which bears hydroxyl groups at six different positions to be the most efficient of all the flavonoid compounds examined. The positions include C3 of the C-ring, C3′ and C4′ of the B-ring as well as C5, C6, and C7 of the A-ring. After that, it was summarized that the presence of hydroxyl groups at C3′ and C4′ in the B-ring and the C2–C3 double bond were found to be critical variables for inhibition, as is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The structure of 44 and the functional groups responsible for the inhibition of glycogen phosphorylase [46].

Matsuda et al. studied the aldose reductase inhibitory action of flavonoids and the structure–activity relationship [47]. Aldose reductase is a central enzyme in the polyol pathway that has been shown to catalyze glucose reduction to sorbitol, which has been linked to a diabetic impact. There are several important structural features that have been discussed by the authors. Firstly, it was found that flavones with no hydroxyl group at position C5 of the A-ring had equivalent bioactivity when compared to chrysin (17a) that is bearing C5-OH. It was hypothesized that the hydroxyl group at C5 may not be essential for inhibition against aldose reductase. Then, it was reported that diosmetin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (45) had weaker inhibition compared to diosmetin (17f). Therefore, it can be assumed that 7-O-glucosyl moiety can lead to a reduction in inhibitory action. The presence of the hydroxyl group at C3 was shown to reduce inhibition, which is supported by the fact that 3-O-methyl or 3-O-monosaccharide derivatives are better inhibitors than the comparable free flavonols at the C3 position. Next, apigenin (17c) inhibited more effectively than kaempferol (6), implying that the presence of the 3-OH group is not essential for the higher inhibition. Lastly, the authors mentioned that flavonoids with catechol moiety at the B-ring (hydroxyl groups at C3′ and C4′) demonstrated better inhibition than flavonoids with pyrogallol moiety (hydroxyl groups at C3′, C4′, and C5′ positions).

Matsuda et al. [48] further investigated the structural requirements of flavonoids for the suppression of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) production. AGEs are one of the consequences of persistent hyperglycaemia, a condition that diabetic individuals endure. It was proposed that increasing the number of hydroxyl groups at C3′ and C4′ of the B-ring, as well as the C5 and C7 locations of the A-ring, can increase flavones’ inhibition against AGE production. Following that, the methylation or glycosylation (i.e., the introduction of sugar moiety) of the hydroxyl group at C3′ or C4′ can reduce the inhibitory action of AGE production. It was also shown that the direct attachment of a sugar moiety to the OH group of the C7 position at the A-ring of flavones and isoflavones decreased inhibitory action. However, the methylation of the flavonols hydroxyl group at C3 of the C-ring appeared to boost activity.

Next, Matsuda et al. investigated the effect of 44 flavonoids on the adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 adipocyte cells [49]. The structural analysis that had been summarized by the authors reported that most flavonoids bearing hydroxyl groups lacked the effect of promoting the accumulation of triglyceride (TG), which acts as a marker of adipogenesis. However, flavonols with methoxy groups exerted a stronger escalation of TG concentration, especially those with a methoxy group at the C3 position. Flavonol’s methoxy group at the B-ring was also found essential for increasing TG.

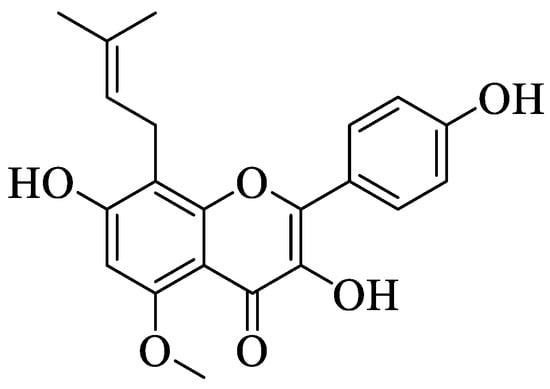

Jung et al. investigated a prenylated flavonol called sophoflavescenol (46) (Figure 2) for its antidiabetic potential [50]. Briefly, 46 was extracted from a Northeast Asian perennial shrub called Sophora flavescens Ait. This study experimented with the inhibition of 46 against rat lens aldose reductase (RLAR), human recombinant aldose reductase (HRAR), and advanced glycation end products (AGE). For RLAR inhibition, 46 showed a significant IC50 value (0.30 μM) when compared to the control, epalrestat (0.07 μM). For HRAR inhibition, 46 also showed a remarkable IC50 value (0.17 μM) compared to the control, epalrestat (IC50 0.15 μM). Meanwhile, for AGE inhibition, 46 portrayed a stronger inhibition with a lower IC50 value (17.89 μg/mL) when compared to the control, aminoguanine (IC50 81.05 μg/mL). The authors discussed that there are three important structural characteristics that contributed to the remarkable RLAR, HRAR, and AGE inhibitions. Firstly, flavonols with a prenyl group at the C8 position and C3′,4′-dihydroxyl groups lead to more potent inhibition. Next, the presence of the methoxy group at C-5 also caused stronger inhibition. Lastly, the essential structural characteristic that contributed to the strong inhibition is the presence of the hydroxyl group at the C-4′ position.

Figure 2. Chemical structure of 46 [50].

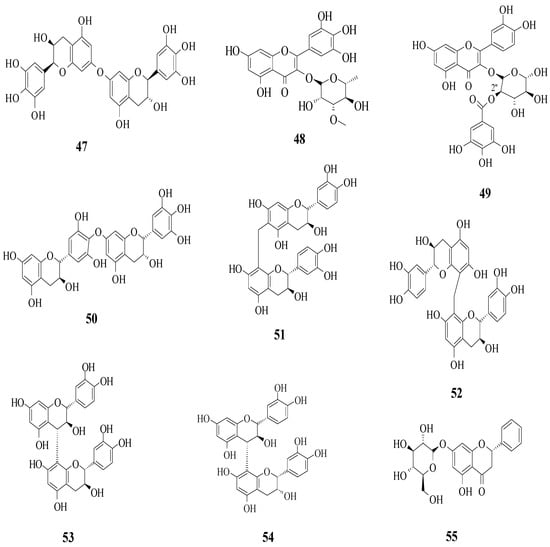

Yang et al. reported the identification of 30 different phenolic compounds from the rhizomes of Potentilla anserina L. [51]. All compounds were tested for their α-glucosidase inhibitory effect by using acarbose as a positive control. As it is well known, inhibiting α-glucosidase is critical in the management of T2D because α-glucosidase catalyses the hydrolysis of starch to simple sugar. All compounds that have been discussed here are displayed in Figure 3. It was reported that several prominent structural characteristics play an important role in stronger inhibition. Firstly, the dimerization of flavonoids was found to be responsible for stronger inhibition. It was proved that compounds 47 and 50–54 belong to the biflavonoid category and portrayed remarkable IC50 values, which ranged from 2.57 to 8.96 μM. Next, the substitution of the gallolyl moiety instead of the glucose moiety at C-2″ can significantly improve the inhibition activity. It can be seen in compound 49 with the gallolyl moiety at C-2″ (IC50 = 1.05 μM) compared to compounds 48 with the glucose moiety and 1 (82.47 and 75.80 μM). The presence of a hydroxyl group in the B-ring was discovered to be essential, as evidenced by compound 55′s weak inhibition (IC50 = 155.57 μM).

Figure 3. The flavonoids isolated as α-glucosidase inhibitors from P. anserine [51].

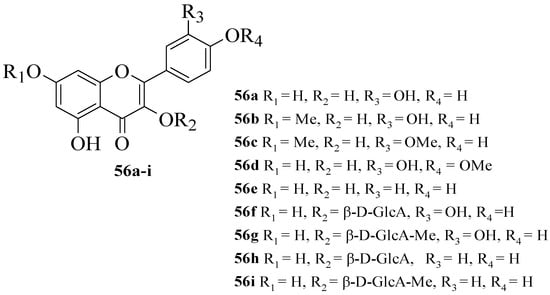

Hmidene et al. studied the effect of five simple flavonols 56a–e and glucuronirated flavonols 56f–i from Tamarix gallica on α-glucosidase inhibitory activity [52]. The acarbose was used as a positive control. The chemical structures of all the compounds tested are elucidated in Figure 4. It was reported that all nine compounds showed a dose-dependent inhibition and portrayed higher inhibition compared to acarbose. Based on compounds 56a and 56e, it was suggested that the hydroxyl group at C3′ with glucuronic acid and methyl ester was responsible for α-glucosidase inhibition.

Figure 4. The structures of flavonoids isolated from T. gallica [52].

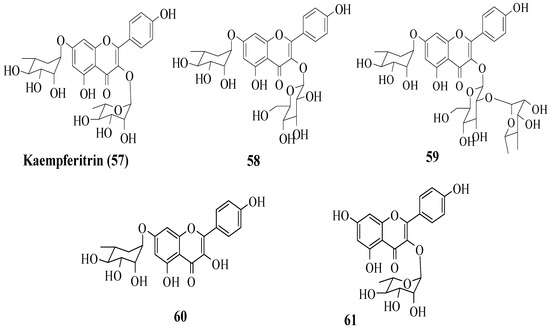

Da Silva et al. investigated the in vivo antidiabetic activity of kaempferol derivatives that were isolated from Sedum dendroideum leaf extract [53]. There were five derivatives tested in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice for acute hypoglycaemic activity. The compounds tested are shown in Figure 5. It was reported that rhamnosyl units at positions 3 and 7 were responsible for the hypoglycaemic activity. In other words, a rhamnosyl unit at position C3 is important as it is present in kaempferitrin (57) but not in 58 and 59, and the results showed 57 had higher hypoglycaemic activity compared to 58 and 50. Next, to test the importance of the rhamnosyl unit at C7, 60 (with rhamnosyl unit at C7) and 61 (without rhamnosyl unit at C7) were tested. The results supported that a rhamnosyl unit at C7 is important as 60 exhibited hypoglycaemic activity after 120 min, but 61 showed activity after 60 min and lost activity at 120 min.

Figure 5. The structures of flavonoids isolated from S. dendroideum [53].

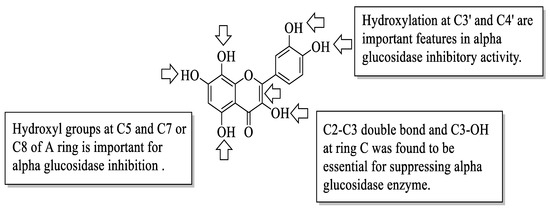

Proença et al. evaluated the series of 40 flavonoids for an in vitro α-glucosidase inhibition. The compounds were grouped into five groups [54]. After testing all the compounds’ α-glucosidase inhibitory activity against acarbose, the authors created a pattern of structural characteristics that were responsible for the activity. The pattern was created based on the most active compounds with IC50 values of 7.6 ± 0.4 μM and 15 ± 3 μM. Based on Figure 6, the presence of hydroxyl groups at the C5 and C7 or C8 positions of the A-ring is important. Next, the hydroxyl groups at C3′ and C4′ of the B-ring were also important for the inhibition. Then, in the C-ring, the C2–C3 double bond and the hydroxyl group at C3 were important. Furthermore, the authors mentioned that the position and amount of hydroxyl groups were the determinants for the α-glucosidase inhibition of flavonoids.

Figure 6. The SAR of flavonoids for α-glucosidase inhibition activity [54].

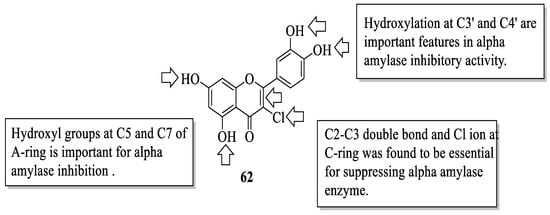

Similarly, Proença et al. studied the same series of 40 flavonoids. However, the bioactivity tested was slightly different, in which inhibition against pancreatic α-amylase was evaluated [55]. Like α-glucosidase inhibition, α-amylase inhibition is also considered one of the T2D management, as it catalyses the hydrolysis of starch to simple sugar. Acarbose was also used in this study as a positive control. It was revealed that the compound with the most effective inhibition was 62 (3-chloro-3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone) with an IC50 value of 44 ± 3 μM. Then, based on this most-active compound, an activity pattern was created by the authors. Based on Figure 7, it was found that the presence of a Cl atom at C3 and the C2–C3 double bond of the C-ring was important for strong inhibition. Furthermore, the presence of hydroxyl groups at C5 and C7 of the A-ring, as well as C3′ and C4′ of the B-ring was also responsible for α-amylase inhibition. In addition, the authors discussed that the position and nature of substituents were also the determinants for the α-amylase inhibition of flavonoids.

Figure 7. The SAR of flavonoids for α-amylase inhibition activity [55].

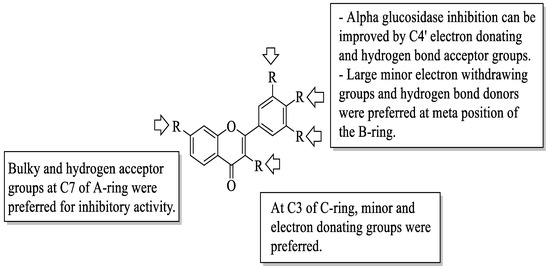

Next, Jia et al. studied several dietary flavonoids for their α-glucosidase inhibitory and insulin-sensitizing potentials [56]. For α-glucosidase inhibition, 27 dietary flavonoids were tested against a positive control, acarbose. The results revealed that three compounds demonstrated remarkable inhibition based on the IC50 value. The values reported were myricetin (12) (IC50 = 11.63 ± 0.36 μM) > apigenin-7-O-glucoside (63) (IC50 = 22.80 ± 0.24 μM) > fisetin (7) (IC50 = 46.39 ± 0.34 μM). Then, by using the 3D-quantitative structure-activity relationship model, structural characteristics that were needed for good inhibition were summarized. There are four important characteristics that can be seen in Figure 8. Firstly, an electron-donating group and hydrogen bond acceptor groups at C4′ of the B-ring can improve the inhibition. In the same B-ring, bulky, minor, electron-withdrawing groups and hydrogen bond donors were favoured at the meta-position. Next, minor and electron-donating groups, as well as hydrogen bond donor groups, were favoured at C3 of the C-ring. After that, at C7 of the A-ring, bulky and hydrogen acceptor groups were favoured. Then, for insulin sensitization activity, all compounds were tested by using molecular docking and in vitro evaluation with insulin-resistant HepG2 cells. The results showed five flavonoids that exerted good insulin sensitization activity which were baicalein (64), isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (65), 63, kaempferol-7-O-β-glucoside (66), and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (67). There was no structural analysis conducted on these five flavonoids for insulin sensitization. However, from both studies, the authors concluded that compound 63 can be used in diabetes management in the future as it exerted excellent activity in both α-glucosidase inhibition and insulin sensitization.

Figure 8. The SAR of flavonoids for α-glucosidase inhibition activity [56].

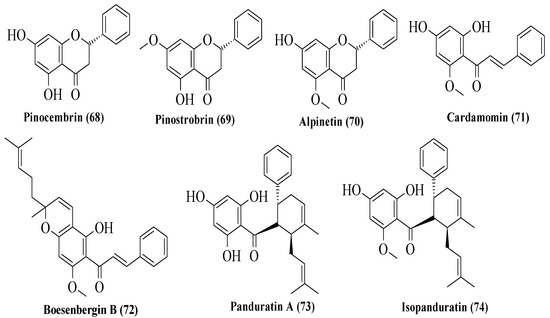

Potipiranun et al. isolated several flavonoids to test their activities on antidiabetic complication (AGE inhibition) and α-glucosidase inhibition [57]. Three flavanones, two chalcones, and two dihydrochalcones were isolated from Boesenbergia rotunda, which is known as fingerroot. Based on Figure 9, flavanones consist of pinocembrin (68), pinostrobin (69), and alpinetin (70). Meanwhile, chalcones are cardamomin (71) and boesenbergin B (72), whereas dihydrochalcones are panduratin A (73) and isopanduratin (74). For the evaluation of AGE inhibition, two methods were conducted, namely AGE inhibition assay and methylglyoxal (MG) trapping activity. MG is a known precursor of glycation. It was reported that most compounds showed greater AGE inhibition than the control, aminoguanidine. Then, for MG trapping activity, all compounds showed comparable activities compared to aminoguanidine. Briefly, 68 was the most active compound for MG trapping activity, with an EC50 value of 63.22 ± 10.12 µM. By using the structure of 68 and other compounds, the SAR of flavonoids on the MG trapping activity was summarized. Firstly, hydroxy groups can improve the inhibition, while methoxy and geranyl groups can reduce the inhibition. Next, the presence of a methoxy group at the C7 position of dihydrochalcone can improve the activity compared to methoxy groups at the C5 position. After that, for α-glucosidase inhibition, only bioactivity studies were conducted, while no SAR was conducted. It was reported that 68 also demonstrated an inhibitory effect against α-glucosidase.

Figure 9. The structures of flavonoids isolated from B. rotunda [57].

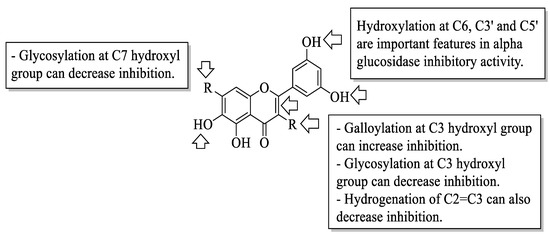

Xiao et al. reviewed an α-glucosidase inhibitory effect of dietary flavonoids and summarized important structural characteristics that were responsible for the inhibition [58]. The summary of the characteristics that influenced the inhibition is illustrated in Figure 10. Based on Figure 10, the presence of hydroxyl groups at C6 of the A-ring and C3′ and C5′ of the B-ring can increase the activity of flavonoids on α-glucosidase inhibition. Next, the galloylation of the hydroxyl group of C3 of the C-ring can also influence the inhibition. In contrast, the hydrogenation of C2=C3 of the C-ring, as well as the attachment of sugar moiety to the hydroxyl groups of C3 of the C-ring and C7 of the A-ring, would decrease the inhibitory activity.

Figure 10. The SAR of flavonoids for α-glucosidase inhibition activity [58].

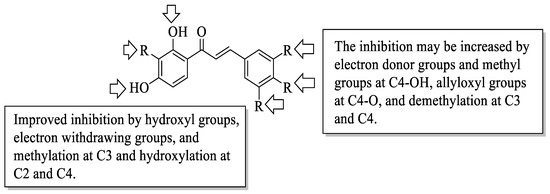

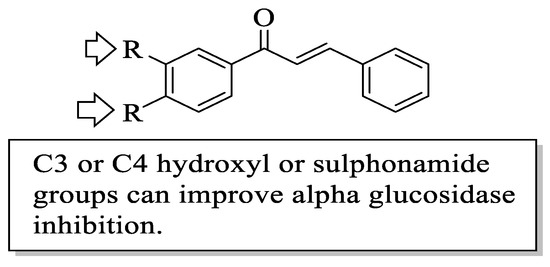

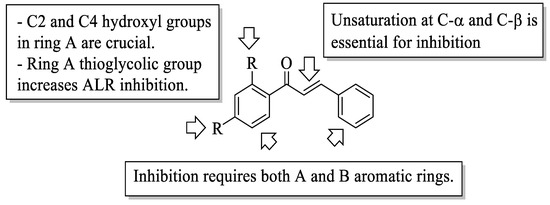

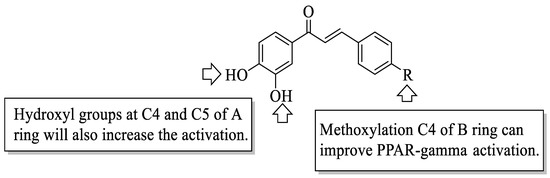

Mahapatra et al. reviewed all SAR studies that were related to the antidiabetic activities of chalcones from 1977 to 2014 [59]. Then, the authors narrowed down the activities into four different effects, namely, the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitory effect, the α-glucosidase inhibitory effect, the aldose reductase (ALR) inhibitory effect, and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma-activating effect. The role of α-glucosidase and ALR was discussed previously. Meanwhile, PTP1B is a prime enzyme responsible for insulin receptor desensitization, and the activation of PPAR gamma plays a critical role in glucose homeostasis by regulating cellular differentiation and development, and the metabolism of carbs, lipids, and proteins [60,61]. All structural characteristics that influenced the bioactivities have been summarized and illustrated. Firstly, based on Figure 11, there are several characteristics that influenced the PTP1B inhibition of chalcones. The hydroxyl groups, electron-withdrawing groups, methylation at C3′, and the hydroxyl groups at C2′ and C4′ of the A-ring can improve the inhibition. Meanwhile, electron-donating groups; methyl groups substitution with the -OH of C4; allyloxyl groups at the -O of C4; demethylation at C3 and C4; and allyl group at C5 of the B-ring may increase the inhibition. After that, for α-glucosidase inhibition, based on Figure 12, hydroxyl groups and sulphonamide groups at C3′ or C4′ of the A-ring can lead to better inhibition. Next, for ALR inhibition, four structural characteristics that were found to be important for ALR inhibition can be seen in Figure 13. The aromatic ring for both the A and B-rings, unsaturation at Cα and Cβ, and hydroxyl groups at C2′ and C4′ of the A-ring are essential. Meanwhile, the introduction of a thioglycolic group at the A-ring will increase the ALR inhibition. Lastly, for PPAR-gamma activation, the methoxy group at C4 of the B-ring, as well as hydroxyl groups at C4′ and C5′ of the A-ring, will increase the activation (Figure 14).

Figure 11. SARs of chalcones for PTP1B inhibition activity [59].

Figure 12. SARs of chalcones for α-glucosidase inhibition activity [59].

Figure 13. SARs of chalcones for ALR inhibition activity [59].

Figure 14. SARs of chalcones for PPAR-gamma activation activity [59].

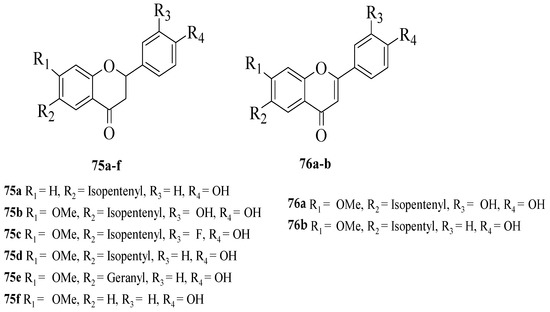

Du et al. synthesized several flavonoid derivatives to be tested as PPAR-γ agonists [62]. The synthesized flavonoids are shown in Figure 15. It was discovered that 75c–d and 76b (EC50 = 3.30, 13.61 and 3.55 μM, respectively) exerted higher activity compared to the control, bavachinin (EC50 = 18.74 μM). Then, the authors reported that removing the C7-methoxy group which can be seen in 75a or removing the C6-isopentenyl chain and then replacing it with a geranyl chain (as can be seen in 75e) can reduce the PPAR-γ activation. In contrast, the replacement of isopentenyl with isopentyl at C6 of the A-ring (75d) can improve the activity. The presence of an electron-donating group (75b) or electron-withdrawing group (75c) at C3′ was found to increase the PPAR-γ activation. Moreover, it was found that the activity was reduced by oxidising the C-ring of flavanone 75b to flavone 75a. Interestingly, oxidising the C-ring of flavanone 75d to produce flavone 76b boosted PPAR-γ activation.

Figure 15. The chemical structures of studied flavonoids for PPAR-γ activation [62].

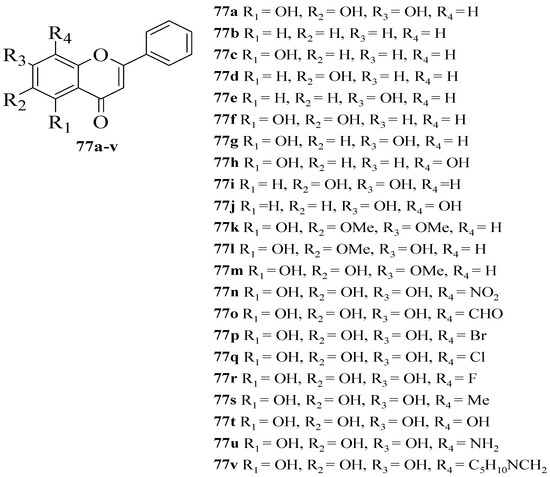

Gao et al. synthesized several flavone derivatives and investigated the effect of the A-ring hydroxyl groups on α-glucosidase inhibition [63]. The flavones that were discussed are shown in Figure 16. It was reported that 77a with trihydroxyl groups was the most potent inhibitor, with an IC50 value of 45 μM. Then, it was found that compounds 77b–j in which there was an absence of any hydroxyl group at C5, C6, and C7 showed either weaker inhibition or inactivity. Most importantly, 77g without C6-OH showed no inhibition, which led the authors to conclude that C6-OH is essential for inhibitory action. Next, 77t was also shown to exert weaker inhibition when the hydroxyl group was added to position C8, despite having three hydroxyl groups pattern at C5, C6, and C7. Following that, the inclusion of an electron-withdrawing or electron-donating group at C8, as can be seen in 77n–q and 77s–u, resulted in either inactivity or became weak in terms of inhibition, despite the fact that 77r lost a little amount of activity. Compound 77v that contained bulky piperidino-methyl group at C8 was also found inactive. Hence, the researchers speculated that 77r’s less bulky fluorine at C8 was responsible for its moderate activity compared to others. It can be concluded that C6-OH and substitution at C8 can influence the inhibition.

Figure 16. The chemical structures of synthesized flavone derivatives that were investigated for α-glucosidase inhibition [63].

Sarian et al. isolated several flavonoids from the Tetracera indica (Houtt. ex Christm. and Panz.) Merr. (Dilleniaceae) and Tetracera scandens (Linn.) Merr. (Dilleniaceae) leaf extracts and then evaluated their antidiabetic effects via α-glucosidase and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-4) inhibition assays [64,65,66,67] (Table 1). The role of α-glucosidase is as discussed previously; meanwhile, the DPP-4 enzyme is involved in the breakdown of incretins such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), then inhibiting it and consequently lengthening the half-life of GLP-1, thereby extending the half-life of insulin. For α-glucosidase inhibition, the authors revealed that quercetin (1) possessing a catechol moiety showed the highest inhibition compared to other isolated compounds. Isoscutellarein (78) and kaempferol (6) with C4-OH showed weaker inhibition compared to 1. Therefore, the catechol group, in which the hydroxyl groups at C3′ and C4′ of the B-ring, were thought to be crucial in α-glucosidase inhibition. Next, for DPP-4 inhibitory action, 1, 78, hypoletin (79), and 6 showed remarkable inhibition. The presence of hydroxyl groups can be considered to affect the inhibitory effect of DPP-4. The absence of a C2–C3 double bond and a 4-oxo group can further reduce the inhibition of α-glucosidase and DPP-4, according to the results of the study.

Table 1. In vitro anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic activities of flavonoids.

| Anti-Inflammatory Activities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | Flavonoids | Assay | Negative Control | Activity of Flavonoids | Std Dev | Positive Control |

Std Dev | |

| [25] | Quercetin (1) | Suppressive action on the transcriptional activity of the COX-2 gene in human colon cancer DLD-1 cells Reporter gene assay |

N/A | IC50 10.5 μM | 0.7 | N/A | N/A | |

| Rhamnetin (2) | IC50 18.6 μM | 2.1 | ||||||

| Genistein (3) | IC50 20.7 μM | 1.4 | ||||||

| Eriodyctiol (4) | IC50 22.0 μM | 0.2 | ||||||

| Luteolin (5) | IC50 22.0 μM | 0.4 | ||||||

| Kaempferol (6) | IC50 39.3 μM | 2.1 | ||||||

| Fisetin (7) | IC50 47.9 μM | 2.9 | ||||||

| Phloretin (8) | IC50 52.5 μM | 3.4 | ||||||

| Catechin (9) | IC50 415.3 μM | 25.4 | ||||||

| Epicatechin (10) | IC50 415.3 μM | 17.0 | ||||||

| Epigallocatechin (11) | IC50 >500 μM | - | ||||||

| Myricetin (12) | IC50 >500 μM | - | ||||||

| [27] | 5 | Inhibition of the generation of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) by human neutrophils | N/A | IC50 1.6 μM | 0.3 | Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), IC50 56.6 μM | 2.5 | |

| 3′,4′-dihydroxy flavone (14d) | IC50 1.7 μM | 0.1 | ||||||

| 3′,4′,7-trihydroxy flavone (16d) | IC50 2.0 μM | 0.7 | ||||||

| 3′,4′,5-trihydroxy flavone (15d) | IC50 2.9 μM | 0.8 | ||||||

| 1 | IC50 4.0 μM | 1.2 | ||||||

| [28] | 1 | Inhibition on rabbit reticulocyte 15-LOX-1 | N/A | IC50 4.0 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 5 | IC50 0.6 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Naringenin (18) | IC50 250 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Hesperidin (19) | IC50 90 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 10 | IC50 60 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Taxifolin (13) | IC50 25 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 1 | Inhibition on soybean LOX L-1 | N/A | IC50 4.5 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| 5 | IC50 3.0 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 13 | IC50 1000 μM | N/A | ||||||

| [29] | 1 | Inhibitory effect on LTB4 production | N/A | IC50 2.0 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 3′-O-methylquercetin (20) | IC50 2.0 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Quercetin-3′-O-sulfate (21) | IC50 2.0 μM | N/A | ||||||

| [32] | 28 | Anti-inflammatory effect on murine macrophage cell line and gastric epithelial cell (GES-1) | N/A | IC50 53.40 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 29 | IC50 120.98 μM | |||||||

| 30 | IC50 10.73 μM | |||||||

| [33] | Isoorientin (26) | Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) inhibition | N/A | IC50 8.9 μg/mL | N/A | Parthenolide, IC50 0.9 μg/mL | N/A | |

| Orientin (31) | IC50 12.0 μg/mL | N/A | ||||||

| Isovitexin (32) | IC50 18.0 μg/mL | N/A | ||||||

| 26 | Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibition | IC50 48.0 μg/mL | N/A | Parthenolide, IC50 0.18 μg/mL | N/A | |||

| 31 | IC50 54.0 μg/mL | N/A | ||||||

| 32 | IC50 21.0 μg/mL | N/A | ||||||

| [37] | Apigenin (17c) | Inhibition of NO production | 7-Nitroindazole, IC50 > 100 μM |

IC50 23 μM | N/A | 2-amino-5,6-dihydro-6-methyl-4H-1,3-thiazine Hydrochloride (AMT), IC50 0.09 μM |

N/A | |

| 5 | IC50 27 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 18 | IC50 >100 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Apiin (34) | IC50 >100 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Galangin (35) | IC50 >100 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 1 | IC50 107 μM | N/A | ||||||

| [39] | 37 | Inhibition of NO production | N/A | IC50 19.87 μM | 0.21 | Hydrocortisone, IC50 3.83 μM | 0.12 | |

| 38 | IC50 15.69 μM | 0.16 | ||||||

| 39 | IC50 9.19 μM | 0.07 | ||||||

| 40 | IC50 10.32 μM | 0.08 | ||||||

| 41 | IC50 18.43 μM | 0.19 | ||||||

| Antidiabetic activities | ||||||||

| References | Flavonoids | Assay | Negativecontrol | Activity of flavonoids | Std Dev | Positive control |

Std Dev | |

| [46] | Quercetagetin (3,3′,4′,5,6,7-Hexahydroxyflavone [44]) | Glycogen phosphorylase inhibition | N/A | IC50 9.7 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| [47] | Chrysin (17a) | Rat lens aldose reductase (RLAR) inhibition | N/A | IC50 8.5 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Diosmetin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (45) | IC50 23.0 μM | N/A | ||||||

| Diosmetin (17f) | IC50 8.5 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 17c | IC50 2.2 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 6 | IC50 10.0 μM | N/A | ||||||

| [50] | Sophoflavescenol (46) | Rat lens aldose reductase (RLAR) inhibition | N/A | IC50 0.30 μM | 0.06 | Epalrestat, IC50 0.07 μM | 0.00 | |

| Human recombinant aldose reductase (HRAR) inhibition | N/A | IC50 0.17 μM | 0.03 | Epalrestat, IC50 0.15 μM | 0.01 | |||

| Advanced glycation end products (AGE) inhibitory activity | N/A | IC50 17.89 μM | 1.44 | Aminoguanidine, IC50 81.05 μM | 0.35 | |||

| [51] | 47 | α-glucosidase inhibition | N/A | IC50 8.96 μM | 0.90 | Acarbose, IC50 28.06 μM | 0.82 | |

| 48 | IC50 82.47 μM | 0.22 | ||||||

| 1 | IC50 75.80 μM | 0.81 | ||||||

| 49 | IC50 1.05 μM | 0.03 | ||||||

| 50 | IC50 3.76 μM | 0.17 | ||||||

| 51 | IC50 2.57 μM | 0.25 | ||||||

| 52 | IC50 3.02 μM | 0.54 | ||||||

| 53 | IC50 2.99 μM | 0.86 | ||||||

| 54 | IC50 3.22 μM | 0.01 | ||||||

| 55 | IC50 155.57 μM | 1.27 | ||||||

| [55] | 62 | Pancreatic α-amylase inhibition | N/A | IC50 44 μM | 3.0 | Acarbose, IC50 1.3 μM | 0.2 | |

| [57] | 12 | α-Glucosidase inhibition | N/A | IC50 11.63 μM | 0.36 | Acarbose, IC50 0.59 μM | 0.14 | |

| Apigenin-7-O-glucoside (63) | IC50 22.80 μM | 0.24 | ||||||

| 7 | IC50 46.39 μM | 0.34 | ||||||

| Pinocembrin (68) | α-Glucosidase inhibition (Sucrase activity) | N/A | IC50 0.39 μM | 0.02 | Acarbose | N/A | ||

| Pinocembrin (68) | α-Glucosidase inhibition (Maltase activity) | N/A | IC50 0.35 μM | 0.021 | ||||

| [62] | 75a | PPAR-γ agonism | N/A | EC50 47.07 μM | N/A | Bavachinin, EC50 18.74 μM | N/A | |

| 75b | EC50 11.25 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 75c | EC50 3.30 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 75d | EC50 13.61 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 75e | EC50 114.33 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 75f | Inactive | N/A | ||||||

| 76a | EC50 42.53 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 76b | EC50 3.55 μM | N/A | ||||||

| [63] | 77a | α-Glucosidase inhibition | N/A | IC50 45 μM | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 77r | IC50 86 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 77t | IC50 960 μM | N/A | ||||||

| 77u | IC50 1000 μM | N/A | ||||||

| [64] | 1 | α-Glucosidase inhibition | IC50 4.92 μg/mL | 7.06 | Quercetin (commercial), IC50 4.30 μg/mL | 1.06 | ||

| Isoscutellarein (78) | IC50 7.15 μg/mL | 0.96 | ||||||

| 6 | IC50 12.19 μg/mL | 4.63 | ||||||

| Hypoletin (79) | IC50 48.42 μg/mL | 9.71 | ||||||

| 1 | DPP-4 inhibition | IC50 21.75 μg/mL | 5.81 | Sitagliptin, IC50 24.51 μg/mL | 1.01 | |||

| 78 | IC50 22.32 μg/mL | 1.52 | ||||||

| 6 | IC50 45.93 μg/mL | 8.61 | ||||||

| 79 | IC50 34.89 μg/mL | 7.44 | ||||||

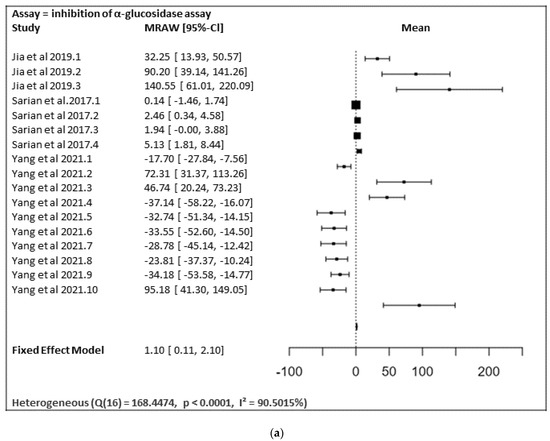

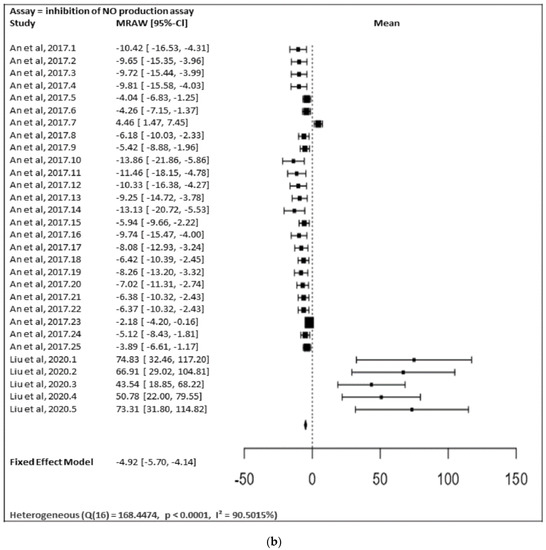

In Figure 17a,b, the meta-analysis for anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic assays activities is shown based on the data given in Table 1. Due to incomplete data, only two studies from the inhibition of the NO production assay and three studies from the inhibition of the α-glucosidase of flavonoids were included in the meta-analysis, as summarized in Figure 17a,b, respectively.

Figure 17. (a) Forest plot from meta-analysis of antidiabetic (inhibition of α-glucosidase) activity. (b) Forest plot from meta-analysis of anti-inflammatory (inhibition of NO production) activity.

Figure 17a shows the meta-analysis using a fixed effect model. It has revealed that the flavonoids, particularly those containing substitutions at positions 5, 3′, and 4′, showed a notable α-glucosidase inhibitory effect (MRAW = 1.1046 (95% CI: 0.1065–2.1027) overall. A total of k = 17 studies were included in the analysis. The observed standardized mean differences ranged from −37.1429 to 140.5504, with the majority of estimates being positive (59%). Therefore, the average outcome differed significantly from zero (z = 2.1690, p = 0.0301). According to the Q-test, the true outcomes appear to be heterogeneous (Q (16) = 168.4474, p < 0.0001, I² = 90.5015%).

Figure 17b shows the meta-analysis using a fixed effect model. It revealed that the flavonoids possessing substitutions at the 5, 3′, and 4′ positions of the A-ring and the B-ring, respectively, showed a notable inhibition of NO production activity (MRAW = −4.9200 (95% CI: −5.6975 to −4.1424). A total of k = 30 studies were included in the analysis. The observed standardized mean differences ranged from −13.8567 to 74.8310, with the majority of estimates being negative (80%). Therefore, the average outcome differed significantly from zero (z = −12.4014, p < 0.0001). According to the Q-test, the true outcomes appear to be heterogeneous (Q (29) = 155.3766, p < 0.0001, I2 = 81.3357%).

In contrast, the inhibition of the generation of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) by human neutrophils, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) inhibition, the inhibition of the generation of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) by human neutrophils, pancreatic α-amylase inhibitory activity, rat lens aldose reductase (RLAR) inhibitory activity, human recombinant aldose reductase (HRAR) inhibitory activity, the advanced glycation end products (AGE) inhibitory activity assay, and the DPP-4 enzyme inhibitory assay were performed as only one study; therefore, a heterogenic analysis was not possible.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms232012605

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!