Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Intending to enhance educational outcomes for indigenous students, who have long been undervalued in many present educational systems, there is an increasing variety of educational interventions in mathematics learning. This is in line with two of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are quality education and reduced inequalities, especially among indigenous students. Nevertheless, no research on indigenous students, locally known as Orang Asli, has been performed in Malaysia.

- indigenous students

- Orang Asli

- mathematics education

- Malaysia

1. Introduction

The term “Orang Asli” refers to the original people of Peninsular Malaysia since time immemorial. There are at least 18 tribes from the Orang Asli ethnic group in the Malay Peninsula. There are approximately 140,000 Orang Asli in Malaysia, most of whom are concentrated in Peninsular Malaysia. Orang Asli is the earliest group to come to West Malaysia several thousand years ago. However, they still practice Malaysia’s oldest way of life, belief system, and language. Most of them live in the interior, in the river’s upper reaches, and on the edge of the forest near the Malay villages and coastal areas. The Orang Asli can be categorised into three main tribes, namely Negrito, Senoi and Proto-Malay. The Bateq, Mendriq, Jahai, Lanoh, Kintak, and Kensiu ethnic groups make up the Orang Asli Negrito group; they reside in the region surrounding the Titiwangsa range, mainly located on the peninsula’s northern side. The Senoi group lives on the Titiwangsa slopes in Perak, Kelantan, and Pahang. The Senoi group consists of six tribes, namely Che Wong, Semai, Semoq Beri, Jahut, Mahmeri, and Temiar. Meanwhile, the Temuan, Semelai, Jakun, Orang Kanaq, Orang Kuala, and Orang Seletar tribes make up the Proto-Malay Orang Asli ethnic group; they initially resided in coastal, kuala, or valley regions. However, they now have a village area of their own [1].

The Malaysian Ministry of Education (MOE) has made it clear in The Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013–2025 that it is extremely concerned about the academic achievement of Orang Asli students (PPPM 2013–2025). For Orang Asli students and other members of minority groups, the government has invested more in teaching and will do so in the future with physical resources and teaching aids; they will receive extra support and equal access to educational opportunities; these students will enrol in schools by 2025 that are fully equipped with the resources needed to support students and establish a conducive learning environment; they will be instructed by teachers who have undergone additional training to comprehend students’ unique demands and difficulties, as well as the learning and teaching techniques necessary to instruct students with special needs. The Ministry will keep working to give Orang Asli students the chance to receive a superior education tailored to their requirements. There are several student groups whose demands and circumstances differ from those of students in the general population. There is a good chance that they will leave the public school system and will not be able to reach their full potential if it is not managed precisely and their requirements are not satisfied specifically. Students who are Orang Asli make up this group; these students will get the same advantages as others in the Malaysian educational system thanks to initiatives, schools, and programs catering to their unique requirements. Among indigenous and other minority groups, 4% of all Malaysian primary and secondary school students are members of indigenous or other minority groups, including the Penan, Sabah, Sarawak natives, Orang Asli, and Sabah natives. Other than that, 80% of these students reside in Sabah and Sarawak, and 68% live in rural areas (PPPM 2013–2025).

The Orang Asli and Indigenous Education Transformation Plan have been developed since the launch of the PPPM 2013–2025. The plan was created to ensure equity; this complies with mainstream education and provides equal access to education. This transformation is expected to address and improve education problems among the Orang Asli community so that their talents and potential are unearthed alongside what is required in 21st-century education and the country towards the Industrial Revolution (IR 4.0). Furthermore, the agenda of the indigenous people has been given attention in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Two goals related to the agenda are Goal 4: Quality education and Goal 10: Reduced inequality [2].

2. Intervention Characteristics

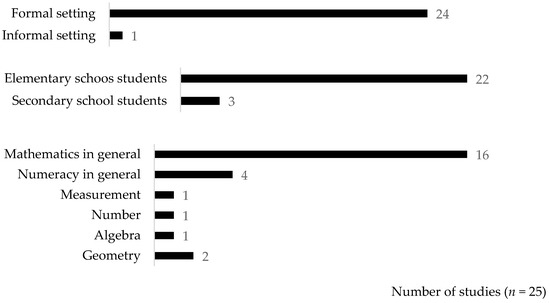

Only one study (4%) of the 25 studies included in the review reported interventions that took place outside of official educational settings and during school hours (e.g., community centres and outdoor settings). For a list of the features of the program, see Figure 1. Each intervention’s patterns of characteristics varied, for example, whether indigenous knowledge holders participated in its implementation, what mathematics concept was involved in the intervention and how long the intervention took place. Even though most interventions occurred in formal settings, the majority involved members of several groups in the implementation of the intervention, including staff from relevant institutions, researchers in education, indigenous knowledge holders, and/or researchers in education. Note that the age range of the participants in these official programs was four to fourteen years old. The youngest samples were 4-year-old students who were exposed to activity-based learning that encouraged them to take part in a context for learning and teaching that was play-based and focused on that age group [3]. In the unstructured context of the study, the intervention took the shape of a 4-day summer camp with planned community and lab activities centred on college access and achievement. Other than that, 14 indigenous high school students participated in this camp, interacting with indigenous people from diverse indigenous communities and sectors [4]. Out of 25 reviewed articles, only three studies (12%) involved secondary school students, while 22 studies (88%) were conducted in elementary schools. Here, mathematics concepts can be divided into six fields (i.e., algebra, geometry, number, measurement, mathematics in general, and numeracy in general). Four studies (16%) involved the topic of numeracy in general, two studies (8%) involved the topic of geometry, and one study (4%) each involved the topic of algebra, numbers and measurement. On the other hand, 16 (64%) studies involved mathematics in general.

Figure 1. Intervention characteristics of the reviewed studies.

3. Features of the Intervention Practice

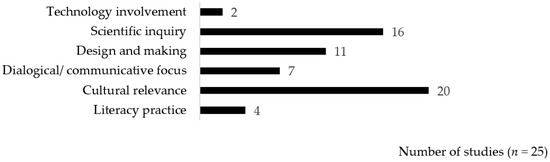

The main focus of the analysis of the practises’ features was on the policies or programs that were put in place to help indigenous students’ mathematical education.. Six categories were referred to coding by Jin [5] i.e., (1) Scientific inquiry refers to activities that involve students in performing scientific studies using scientific (Western) procedures, for example, formulating hypotheses and gathering data through the concept and implementation of experiments, (2) Students participate in practical tasks while designing and making, (3) Cultural relevance refers to the emphasis on Orang Asli knowledge, how to know Orang Asli, relationships with the local community, (4) Technology involvement gives students the opportunity to use software and engage with digital technologies, (5) Focus on discussion and communication, offering students the chance to interact and discuss with their peers through collaborative group work and dialogue, and (6) Literacy exercises concentrate on literacy practises including storytelling, narrative writing, creative writing, and the development of (scientific) vocabulary. Because these coding categories were not mutually exclusive, multiple codes might be used for the same study because they were all appropriate. Regarding the methodologies each intervention used, they all share a variety of features. Due to the complexity of the methodologies used in these interventions, all of the other 25 trials had two or more codes. The features of the interventions examined in this study are displayed in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Features of the intervention practice.

The analysis clearly demonstrated two features: cultural significance and scientific inquiry. In 20 (80%) of the 25 studies that made up this review, indigenous knowledge and/or ways of knowing were included in students’ mathematics instruction, making the interventions culturally appropriate for indigenous students. When building an understanding of arithmetic symbolism that may be easily extended to algebraic symbolism, Matthews et al. [6] adopted an approach that makes use of indigenous knowledge of symbols within domains like sports, driving, art, and dance as a starting point. It was mentioned in Moloi [7], and Nkopodi and Mosimege [8] that Morabara was used as an example of an indigenous game to teach mathematical concepts in a condensed form; they claim that the Morabara game makes it fun to learn mathematical concepts. The efficacy of the indigenous game *kgati (skipping rope) in the teaching and learning of word problems in Grade 4 mathematics was investigated by Moloi et al. [9].

Meanwhile, Hsu et al. [10] investigated the design of a curriculum based on culture, the implementation of teaching, and the impact on the math learning performance of Paiwan children in Grades 5 and 6. Note that 16 of the 25 initiatives, or around two-thirds, placed a strong emphasis on scientific inquiry as they were being implemented. The instructors in Tai [11] were in line with cognitive load theory (CLT) and pertinent studies to instruct students to monitor their own CL while solving mathematics problems, for example, deletion of redundant information, monitoring drawing manifestation, and isolation of element; these programs, like those in Rigney et al. [12], encouraged students to think creatively, engage physically, experiment, and learn from others. For students to be motivated and competent to plan, check, monitor, assess, and correct their cognitive strategy on their own, the teachers give them the necessary tools. There were some other features discovered in addition to cultural relevance and scientific investigation, with 11 (44%) of the 25 interventions having a design and being made. All classroom activities in these interventions, like those in Warren et al. [3], were situated within the early childhood philosophy of activity-based learning, with students being encouraged to participate in a play-based and focused learning and teaching context. Correspondingly, Warren and DeVries [13] provided hands-on learning-based learning that best supports young indigenous students’ engagement with mathematics. Seven studies (28%) placed emphasis on Dialogical/communicative focus. For example, Gardner and Mushin [14] focused on how classroom discussion is structured in these indigenous classrooms to facilitate knowledge transmission as a basis for learning and representations, oral language, and engagement in mathematics. Moreover, RoleM is a mathematics program developed by Warren and Miller [15] with the help of Miller et al. [16]. It is based on research on how to best support the learning of young indigenous students. Four studies (16%) focused on literacy practice, including Matthews et al. [6]; they recommended training and involving students in storytelling and creative writing as well as helping them create and use disciplinary vocabularies for mathematics [13]. Other than that, only two interventions (8%) emphasised Technology involvement. Students in these programs either utilised technological tools for the intervention [17] or took part in the course in a setting where learning is facilitated by technology [18].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su142013201

References

- Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA). Available online: https://www.jakoa.gov.my/orang-asli (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- United Nations. The 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals: An opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean (LC/G. 2681-P/Rev). 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/40156 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Warren, E.; Young, J.; DeVries, E. The impact of early numeracy engagement on four-year-old Indigenous students. Australas. J. Early Child. 2008, 33, 2–8.

- Garcia-Olp, M.; Nelson, C.; Saiz, L. Conceptualizing a mathematics curriculum: Indigenous knowledge has always been mathematics education. Educ. Stud. 2019, 55, 689–706.

- Jin, Q. Supporting indigenous students in science and STEM education: A systematic review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 555.

- Matthews, C.; Cooper, T.; Baturo, A. Creating your own symbols: Beginning algebraic thinking with Indigenous students. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Seoul, Korea, 8–13 July 2007; Woo, J., Lew, H., Seo, D., Park, K., Eds.; The Korea Society of Educational Studies in Mathematics: Seoul, Korea, 2007; pp. 249–256.

- Moloi, T.J. The use of Morabara game to concretise the teaching of the mathematical content. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 585.

- Nkopodi, N.; Mosimege, M. Incorporating the indigenous game of morabaraba in the learning of mathematics. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2009, 29, 377–392.

- Moloi, T.J.; Mosia, M.S.; Matabane, M.E.; Sibaya, K.T. The use of indigenous games to enhance the learning of word problems in grade 4 mathematics: A case of Kgati. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2021, 20, 240–259.

- Hsu, W.M.; Lin, C.L.; Kao, H.L. Exploring teaching performance and students’ learning effects by two elementary indigenous teachers implementing culture-based mathematics instruction. Creat. Educ. 2013, 4, 663–672.

- Tai, C.H.; Leou, S.; Hung, J.F. The effectiveness of teaching indigenous students mathematics using example-based cognitive methods. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2015, 18, 433–448.

- Rigney, L.; Garrett, R.; Curry, M.; MacGill, B. Culturally responsive pedagogy and mathematics through creative and body-based learning: Urban Aboriginal schooling. Educ. Urban Soc. 2020, 52, 1159–1180.

- Warren, E.; DeVries, E. Young Australian Indigenous students’ engagement with numeracy: Actions that assist to bridge the gap. Aust. J. Educ. 2009, 53, 159–175.

- Gardner, R.; Mushin, I. Language for learning in Indigenous classrooms: Foundations for literacy and numeracy. In Pedagogies to Enhance Learning for Indigenous Students; Jorgensen, R., Sullivan, P., Grootenboer, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2013; pp. 89–104.

- Warren, E.; Miller, J. Young Australian Indigenous students’ effective engagement in mathematics: The role of language, patterns, and structure. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 25, 151–171.

- Miller, J.; Warren, E.; Armour, D. Examining changes in young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island students and their beginning primary school teachers’ engagement in the teaching and learning of mathematics. ZDM Math. Educ. 2020, 52, 557–569.

- Jorgensen, R.; Lowrie, T. Both ways strong: Using digital games to engage Aboriginal learners. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 17, 130–142.

- Pegg, J.; Graham, L. A three-level intervention pedagogy to enhance the academic achievement of Indigenous students: Evidence from QuickSmart. In Pedagogies to Enhance Learning for Indigenous Students; Springer: Singapore, 2013; pp. 123–138.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!