Supportive psychotherapy is a psychotherapeutic approach that integrates various therapeutic schools such as psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral, as well as interpersonal conceptual models and techniques. The aim of supportive psychotherapy is to reduce or to relieve the intensity of manifested or presenting symptoms, distress or disability. It also reduces the extent of behavioral disruptions caused by the patient's psychic conflicts or disturbances. Unlike in psychoanalysis, in which the analyst works to maintain a neutral demeanor as a "blank canvas" for transference, in supportive therapy the therapist engages in a fully emotional, encouraging, and supportive relationship with the patient as a method of furthering healthy defense mechanisms, especially in the context of interpersonal relationships. Supportive psychotherapy can be used as treatment for a variety of physical, mental, and emotional ailments, and consists of a variety of strategies and techniques in which therapists or other licensed professionals can treat their patients. The objective of the therapist is to reinforce the patient's healthy and adaptive patterns of thought behaviors in order to reduce the intrapsychic conflicts that produce symptoms of mental disorders.

- supportive therapy

- psychoanalysis

- conceptual models

1. Evolution of Supportive Psychotherapy

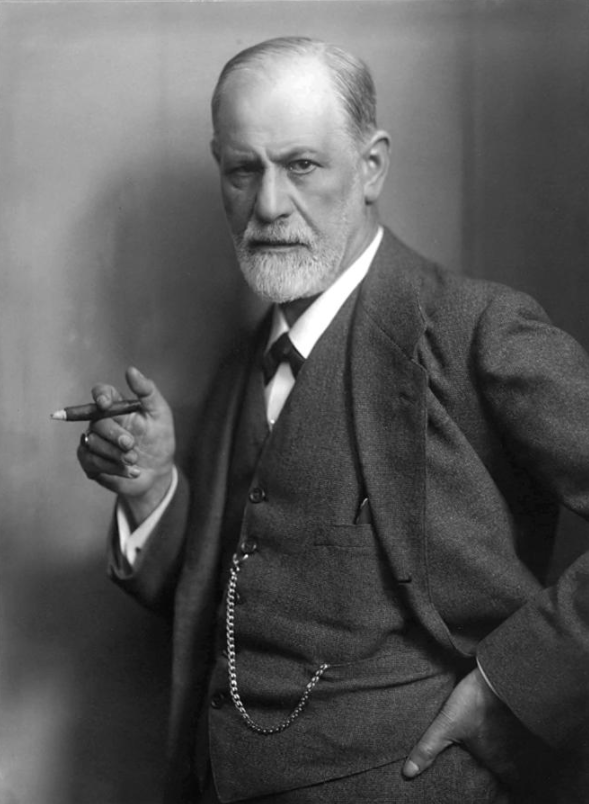

In the late 19th century, Sigmund Freud began to develop the techniques of psychoanalysis, which served as a foundation for all the other psychotherapeutic modalities. Freud found that by letting people talk freely about whatever came to mind (free association), they eventually revealed the origins of their psychological conflicts in disguised form. Upon hearing these confessions revealed through free association, the therapist would then interpret the unconscious cause for the patient’s symptoms.[1]

In the years following Freud’s development of psychoanalysis, this approach was seen as the default in treating mental illness in patients. Psychotherapists faced the problem of patients who were unanalyzable: those without the reflective capacity to hear interpretations, or with “pseudoneurotic schizophrenia”.[2] These patients who would react negatively to psychoanalysis would then receive a more bolstering, “supportive” treatment. This therapy, which would later be recognized as the initial stages of supportive psychotherapy, was not the preferred mode of treatment, not for the preferred patients, and hence, was seen as pejorative from the onset.

Franz Alexander studied Freud, and although he was trained in classical psychoanalytic technique, he began to evolve his own ideas about what allowed the curative process to occur in therapy.[3]

Alexander noted that in classical psychoanalysis, the essential requirement for change was the insight the patient gained from interpretation of the transference neurosis. Alexander agreed with Freud that during psychoanalysis the patient underwent transference based on earlier life experience and emotional traumas. While Freud believed that the insight the patient gained from this was essential for healing to occur, Alexander felt the process of the patient feeling nurtured or comforted while reliving emotional traumas was also a curative force. He began to look at other factors that might be contributing to improvement, factors not related to insight but rather to the relationship of the patient with the psychoanalyst.[3]

The objective of supportive psychotherapy was not to change the patient's personality but to help the patient cope with symptoms, prevent relapse of serious mental illness, or help a relatively healthy person deal with a crisis or transient problem. As defined in earlier years, supportive psychotherapy is a body of techniques, such as praise, advice, exhortation, and encouragement, embedded in psychodynamic understanding and used to treat severely impaired patients.[4]

Over the next few decades and with ample studies to demonstrate efficacy, supportive psychotherapy gained momentum among professionals as a practical and efficacious method of therapy and supportive psychotherapy became recognized as the default treatment for patients with more severe psychological symptoms or those who couldn’t withstand the rigors of psychoanalysis.

2. Context and History

2.1. Context

Supportive psychotherapy is often practiced for patients who are considered lower functioning, too fragile, or too unmotivated to participate in more demanding expressive therapy, which might have more chance of leading to personality change.[5]

As a dyadic treatment that is characterized by use of direct measures to ameliorate symptoms and to maintain, restore, or improve self-esteem, adaptive skills, and psychological (ego) function, the treatment itself works to observe relationships (real or transferential) and both current and past patterns of emotional or behavioral response.[6]

As supportive psychotherapy is introduced in environments less formal than a primary care office, supportive psychotherapy can appear as an expression of interest, attention to concrete services, encouragement and optimism. The relationship between the patient and the professional during supportive treatment exists solely to meet the needs of the patient, and it should not develop as a platonic relationship outside of professionalism.[7]

2.2. History

Supportive psychotherapy functions with the objective of reducing anxiety and maintaining a positive patient-therapist relationship with minimal focus on transference.[5] While this practice of therapy is seldom studied, it has since been identified and functions as an alternative to expressive therapy.[6]

Supportive psychotherapy and supportive treatment works well for patients who are anticipated to fail at expressive therapy, or who are generally difficult to treat with expressive therapy.[6]

An early documentation of supportive psychotherapy can be found in The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research with contributions from David J. Hellerstein, M.D., Henry Pinsker, M.D., Richard N. Rosenthal, M.D., and Steven Klee, Ph.D. In their contributions to the study and exploration of supportive psychotherapy, These researchers note that with supportive and expressive falling on a continuum, the model for individual dynamic psychotherapy should be based on concepts from the supportive end of the continuum, rather than the expressive end.[5]

A summary of Otto F. Kernberg’s definition of supportive psychotherapy is featured in The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research and defines what supportive therapy does rather than what it is.[5] Kernberg’s definition includes actions like:

- reducing behavioral dysfunctions

- reducing subjective mental distress

- supporting and enhancing the patient’s strengths, coping skills, and capacity to use environmental supports

- maximizing treatment autonomy

- facilitating maximum possible independence from psychiatric illness.

3. Uses

Supportive psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in a variety of psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders, and postpartum depression.

Supportive psychotherapy has also shown to be effective in a variety of medical conditions including breast cancer, ovarian cancer, diabetes, leukemia, heart disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, inflammatory bowel disease, back pain, and for hemodialysis patients.[8][9][10][11]

Additionally, supportive therapy is recognized as the treatment of choice for patients seen by psychiatrists and residents who are suffering from extra-psychic problems, such as poverty, social and political oppression, and abuses of power in relationships that threaten to overwhelm their coping capacities.[12]

4. Strategies and Techniques

Strategies and techniques associated with supportive psychotherapy include the following:[1]

4.1. Listening

Argued by author John Battaglia as “the most powerful skill of supportive psychotherapy”,[1] the element of listening in regards to supportive psychotherapy helps patients feel “heard” by their therapists or health professionals. Effective listening “includes careful attentiveness to the body language, emotional tone, and overall bearing of patients in the sessions.”

4.2. Plussing

Plussing is defined as “promoting a positive atmosphere in the therapy by finding the good in the patient and accentuating the positive in the patient’s situation.” Battaglia compares this supportive psychotherapy strategy to “putting on rose-colored glasses and seeing what the patient presents as half full,” and assisting patients with finding a positive outlook even if it appears difficult to find.

4.3. Explaining Behavior or Advice

Using the explaining behavior strategy within supportive psychotherapy allows for therapists and health professionals to lead patients to areas of comfort or security as they navigate complex and overwhelming emotions or compulsions. With this technique, the behavioral explanations brought forth by the professional should aim to make sense to the patient and help them feel supported.

Advice is another supportive psychotherapy strategy that branches from the explaining behavior technique. Advice is effective usually when the patient is able to connect it to their goals. [13]

4.4. Confrontation and Reframing

Confrontation is essentially allowing the patient to reflect and comprehend how their patterns of behavior are contributing to their suffering. Therapists and professionals help guide patients to understanding how repeated behaviors or emotions contribute to their mental health and symptoms.

Reframing is related to the technique of confrontation as reframing involves looking at something in a different light or different angle and can provide patients with a new perspective as they undergo supportive psychotherapy. [13]

4.5. Encouragement or Praise

Encouragement or Praise is often used in doses that are based on preexisting elements of the patient, such as their history, strengths, and weaknesses. Encouragement should be used sparingly in order to avoid the patient experiencing emotions of falling short to what their therapist expected of them. Using encouragement in this environment combines opportunities for education and movement in order to bring patients upward in their treatment or outside of their comfort zone.

Additionally, this technique can be used to reinforce accomplishments or positive changes in behavior, and can be positioned as the reinforcement of the patient's steps towards achieving their stated goals. [13]

4.6. Hope

Very similarly to encouragement, hope is to be used sparingly and appropriately by therapists and health professionals in order to “provide enough hope for the patient to see change as a realistic opportunity.”

4.7. Metaphor

The use of metaphors is a stimulating element of supportive psychotherapy that “[utilizes] different parts of the patient’s brain than those stimulated by many of the other more language based techniques.” A metaphor is said to “stick” in a patient's head in a “very durable way.”

4.8. Coping Skills

Therapists and health professionals assisting patients with developing cognitive and behavioral coping skills is another technique used for supportive psychotherapy. These techniques range in complexity, and can consist of mantras or coping plans for the patient.

4.9. Self-Soothing

Giving patients the tools necessary to develop self-soothing habits in opposition to unhealthy acting-out behavior, such as extreme mood swings, substance abuse, or acting out.

4.10. Creative Opportunities

Creative opportunities allow for therapists and health professionals to introduce their patients to creative outlets in order to express their emotions. Some of these techniques within this strategy include storytelling, journaling, and writing letters they won’t send.

Some techniques identified, but generally avoided and used with caution are humor and comparing pain.

5. Studies on Supportive Psychotherapy

In an extensive longitudinal study developed in the 1950s, the "Menninger Psychotherapy Research Project" compared patients receiving psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and supportive psychotherapy over a 23-year span. The main objective of the study was to critically examine the difference between psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy. The supportive psychotherapy arm of the study was placed more as a control condition than as a rigorous technique for comparison. The study results concluded there were no significant differences among the three different types of psychotherapy.[14]

In one 1978 study looking at treatment of agoraphobia, mixed phobias, or simple phobias, patients were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions: behavior therapy alone, behavior therapy plus imipramine (medication) treatment, or supportive therapy plus imipramine (medication) treatment. Therapists in the behavior therapy groups used a manualized, highly structured treatment protocol that included relaxation training and systematic desensitization in imagination, specific in vivo desensitization homework assignments, and assertiveness training (including modeling, role playing, behavior rehearsal, and in vivo homework assignments). The supportive therapy was nondirective; patients took the initiative in all discussions. The therapists doing supportive therapy were instructed to be empathic and non-judgmental and to encourage patients to ventilate feelings and discuss problems, anxieties, and interpersonal relationships. The researchers found that there were no significant differences between the therapy conditions and that patients did well in both.[15]

In a 2005 randomized controlled study looking at cognitive-behavioral therapy versus interpersonal therapy for anorexia nervosa, once again supportive psychotherapy was used as a control condition. In the cognitive-behavioral therapy arm of the study, the patients underwent several phases of treatment, including psychoeducation, motivational assessment, cognitive-behavioral skills (including thought restructuring and homework assignments), relapse prevention, and recovery strategies.[16]

6. Teaching Supportive Psychotherapy

Researchers Arnold Winston, M.D., Richard N. Rosenthal, M.D., and Laura Weiss Roberts, M.D., M.A. express the elusiveness of the field of supportive psychotherapy: it is not based on “rigorous and internally consistent or appealing theory, it does not offer solutions to intractable clinical problems, and the field itself has no conferences, stars, and relatively few books.”[4]

In Winston’s Rosenthal’s and Robert’s text, “Learning Supportive Psychotherapy, Second Edition: An Illustrated Guide,” these authors note that “The psychotherapist’s central task is learning to understand...the emotional experience of the patient” (Balsam and Balsam), which was presented universally in regards to teaching supportive psychotherapy.

This universal treatment provided little guidance in how to handle patients who were inarticulate or poorly educated, who have intractable social problems, severe behavioral problems, or those who only visited for a couple months at a time or visited biweekly.[3]

In 2012, Adam M. Brenner, M.D. advocated for a “much more sophisticated approach” to teaching health professionals and therapists about supportive psychotherapy, which focused on three important factors of supportive psychotherapy:

- Its relevance for common factors underlying all forms of psychotherapy

- Its role on a spectrum of psychodynamically informed psychotherapies

- Its value as a modality that includes specifically definable techniques and aims

Brenner also advocated for “teaching supportive psychotherapy in diverse clinical rotations, including inpatient and consultation-liaison services as well as ambulatory settings.”[4]

7. Criticism about Supportive Psychotherapy

As the method of supportive psychotherapy grew in popularity among psychologists and healthcare professionals, backlash concerning the effectiveness or validity of nonpsychoanalytic techniques arose. With psychoanalysis, the theory was that once a person improved through gaining insight, he or she underwent a permanent and curative change of personality. By contrast, changes brought about through more supportive types of psychotherapy were seen by critics as behavioral, meaning more transient and specific to the symptoms and not indicative of permanent personality change, which resulted in psychoanalysts believing that supportive-type therapy was not psychotherapy at all.[1]

An additional criticism regarding supportive psychotherapy addresses only problems and conflicts that the patient is aware of. Other types of psychotherapy rely on less direct measures, such as identifying unconscious conflicts. Supportive psychotherapy looks at abstract entities such as defense mechanisms only when they seem maladaptive.[7]

Changes brought about through more supportive types of psychotherapy were seen by critics as behavioral, meaning more transient and specific to the symptoms and not indicative of permanent personality change.[1]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Medicine:Supportive_psychotherapy

References

- Battaglia, John (2019). Doing Supportive Psychotherapy. American Psychiatric. ISBN 978-1-61537-262-1.

- Hoch, Paul; Polatin, Phillip (April 1949). "Pseudoneurotic forms of schizophrenia". The Psychiatric Quarterly 23 (2): 248–276. doi:10.1007/bf01563119. PMID 18137714. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fbf01563119

- Margolin, Sidney G. (July 1946). "ALEXANDER, FRANZ, AND FRENCH, THOMAS: Psychoanalytic Therapy. New York, Ronald Press Company, 1946, 353 pp. $5.00.". Psychosomatic Medicine 8 (4): 285–296. doi:10.1097/00006842-194607000-00010. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2F00006842-194607000-00010

- Winston, Arnold; Roberts, Laura (2019). "Supportive Psychotherapy". The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9781615372980.lr34. ISBN 978-1-61537-298-0. https://dx.doi.org/10.1176%2Fappi.books.9781615372980.lr34

- Hellerstein, David J.; Pinsker, HENRY; Rosenthal, Richard N.; Klee, Steven (1994). "Supportive Therapy as theTreatment Model of Choice". The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 3 (4): 300–306. PMID 22700197. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3330375

- Rosenthal, Richard N.; Muran, J. Christopher; Pinsker, Henry; Hellerstein, David; Winston, Arnold (1999). "Interpersonal Change in Brief Supportive Psychotherapy". The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 8 (1): 55–63. PMID 9888107. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3330523

- Crocker, Erin (11 September 2017). "Supportive Psychotherapy". DeckerMed Psychiatry. doi:10.2310/psych.13060. https://dx.doi.org/10.2310%2Fpsych.13060

- Rockland, Lawrence H. (November 1993). "A Review of Supportive Psychotherapy, 1986-1992". Psychiatric Services 44 (11): 1053–1060. doi:10.1176/ps.44.11.1053. PMID 8288173. https://dx.doi.org/10.1176%2Fps.44.11.1053

- Manne, Sharon L.; Rubin, Stephen; Edelson, Mitchell; Rosenblum, Norman; Bergman, Cynthia; Hernandez, Enrique; Carlson, John; Rocereto, Thomas et al. (August 2007). "Coping and communication-enhancing intervention versus supportive counseling for women diagnosed with gynecological cancers". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 75 (4): 615–628. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.615. PMID 17663615. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0022-006X.75.4.615

- Szigethy, Eva; Bujoreanu, Simona I.; Youk, Ada O.; Weisz, John; Benhayon, David; Fairclough, Diane; Ducharme, Peter; Gonzalez-Heydrich, Joseph et al. (2014). "Randomized Efficacy Trial of Two Psychotherapies for Depression in Youth with Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 53 (7): 726–735. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.014. PMID 24954822. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4104185

- Novalis, Peter (1989). "What Supports Supportive Therapy?". Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry 7 (2). doi:10.29046/JJP.007.2.003. https://dx.doi.org/10.29046%2FJJP.007.2.003

- Rothe, Eugenio M. (24 May 2017). "Supportive Psychotherapy in Everyday Clinical Practice: It's Like Riding a Bicycle". Psychiatric Times 34 (5). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/supportive-psychotherapy-everyday-clinical-practice-its-riding-bicycle.

- "Supportive Psychotherapy for Medical Students" (in en-us). https://med.unr.edu/psychiatry/education/resources/supportive-psychotherapy.

- Wallerstein, Robert S. (1989). "The Psychotherapy Research Project of the Menninger Foundation: An overview". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57 (2): 195–205. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.57.2.195. PMID 2708605. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0022-006x.57.2.195

- Zitrin, Charlotte Marker (1 March 1978). "Behavior Therapy, Supportive Psychotherapy, Imipramine, and Phobias". Archives of General Psychiatry 35 (3): 307–316. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770270057005. PMID 31847. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Farchpsyc.1978.01770270057005

- McIntosh, Virginia V.W.; Jordan, Jennifer; Carter, Frances A.; Luty, Suzanne E.; McKenzie, Janice M.; Bulik, Cynthia M.; Frampton, Christopher M.A.; Joyce, Peter R. (April 2005). "Three Psychotherapies for Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized, Controlled Trial". American Journal of Psychiatry 162 (4): 741–747. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.741. PMID 15800147. https://dx.doi.org/10.1176%2Fappi.ajp.162.4.741