Religion of the Indus Valley Civilization ("IVC") is a debated topic and remains a matter of speculation. If the Indus script is ever deciphered, this may provide clearer evidence. The first excavators of the IVC were struck by the absence of obvious temples or other evidence of religion, and there remain no examples of buildings generally agreed by scholars to have had a religious function, although some suggestions of religious use have been made. The religion and belief system of the Indus Valley people have received considerable attention, especially from the view of identifying precursors to deities and religious practices of Indian religions that later developed in the area. However, due to the sparsity of evidence, which is open to varying interpretations, and the fact that the Indus script remains undeciphered, the conclusions are partly speculative and many are largely based on a retrospective view from a much later Hindu perspective. Geoffrey Samuel, writing in 2008, finds all attempts to make "positive assertions" about IVC religions as conjectural and intensely prone to personal biases — at the end of the day, scholars knew nothing about Indus Valley religions. An early and influential work in the area that set the trend for Hindu interpretations of archaeological evidence from the Harappan sites was that of John Marshall, who in 1931 identified the following as prominent features of the Indus religion: a Great Male God and a Mother Goddess; deification or veneration of animals and plants; symbolic representation of the phallus (linga) and vulva (yoni); and, use of baths and water in religious practice. Marshall's interpretations have been intensely critiqued, and most of his specific details have failed to stand the test of time. Yet, claims Asko Parpola, Marshall's conclusions have been generally accepted. Contemporary scholars (most significantly, Parpola) continue to probe the roles of the IVC in the formation of Hinduism; others remain ambivalent of these results.

- symbolic representation

- religion

- phallus

1. Background

The Indus Valley Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE.[1][2] Together with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of three early civilisations of the Near East and South Asia, and of the three, the most widespread, its sites spanning an area stretching from today's northeast Afghanistan, through much of what is now Pakistan , and into western and northwestern India .[3][4] It flourished in the basins of the Indus River, which flows through India and Pakistan along a system of perennial, mostly monsoon-fed, rivers.[1][5]

In these other civilizations large temples were a central key element of cities, and religious imagery abounded. Once the scripts were decyphered the names of deities, and the characteristics attributed to them, became fairly clear. None of this is the case for the IVC.

2. Seals

The imagery on the great majority of Indus seals centres on a single animal; generally various attempts to attribute religious significance to these have not been widely accepted. But a minority are more complicated and prominently feature figures with a human form, and there has been much discussion of these.

2.1. Pashupati Seal: Proto Shiva

In 1976, Doris Meth Srinivasan mounted the first substantial critique of Marshall's identification.[6] She accepted the figure to be indicative of cultic divinity, that people bowed towards such a posture (on other seals) but rejected the proto-Shiva identification: Pashupati of Vedic Corpus is the protector of domestic animals.[7] On comparison to facial particulars from horned masks and painted vessels, Srinivasan went on to propose the central figure to be a Buffalo-man, who had a "humanized bucranium" and whose headdress imparted powers of fertility.[7] Gavin Flood, about two decades later, noted that neither the Lotus position nor the anthropomorphic form of the central figure was deducible to any certainty.[8] Alf Hiltebeitel rejects a proto-Shiva identification; he supports Srinivasan's thesis with additional arguments, and hypothesize the Buffalo-man to have formed the legend of Mahishasura.[9][10] Gregory Possehl agrees.[11]

Some scholars of Yoga — Karel Werner, Thomas McEvilley et al — have since used it to trace back the roots of Yoga to IVC. However, Geoffrey Samuel, writing in 2008, rejects Marshall's theory as mere anachronistic speculation and goes on to reject that yoga has its roots in IVC, as does Andrea R. Jain (2016) in Selling Yoga.[12] Paleontologist cum Indologist Alexandra Van Der Geer, in her 2008 survey of Indian mammals in art, comments the figure to remain "unknown" until the script is deciphered.[13] Samuel as well as Wendy Doniger had taken a similar stance.[12][14] Kenoyer (as well as Michael Witzel) now consider the image to be an instance of Lord of the Beasts found in Eurasian neolithic mythology or the widespread motif of the Master of Animals found in ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean art, and the many other traditions of horned deities.[15][16]

2.2. "Procession Seal"

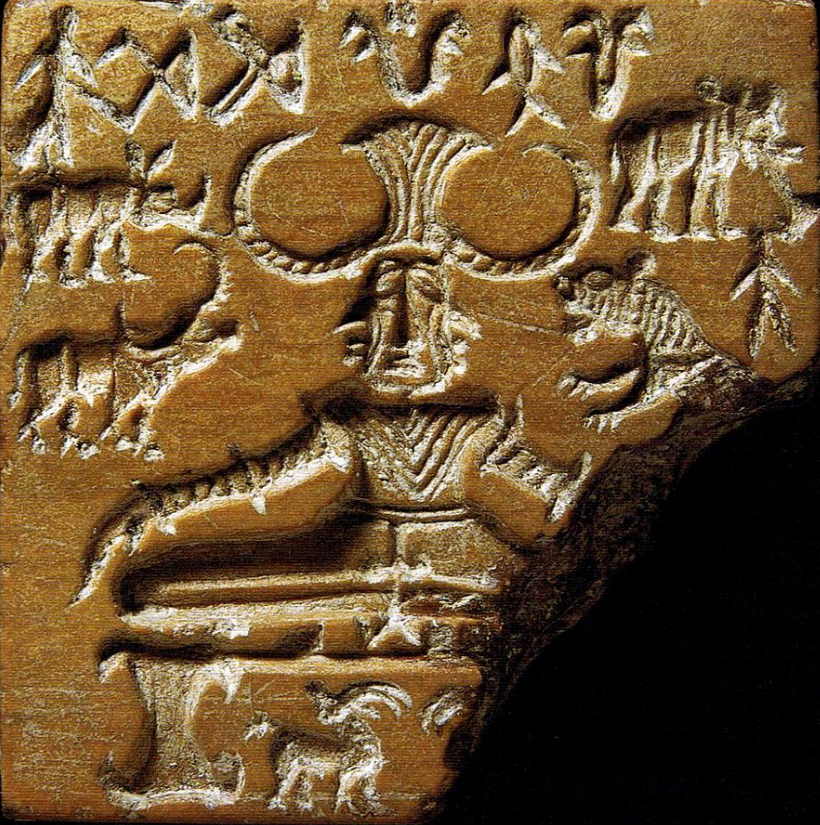

Another seal from Mohenjo-daro (Find no. 420, now Islamabad Museum, 50.295), also called the "sacrifice" seal, of a type with a few examples found, is generally agreed to show a religious ritual of some kind, though readings of the imagery and interpretations of the scene vary considerably. It shows signs of wear from heavy usage. At top left a figure with large horns and bangles on both arms stands in a pipal tree; it is generally agreed this represents a deity. Another figure kneels on one knee in front of this, also shown as horned and perhaps with plumes in a headdress. This is interpreted as a worshipper, perhaps a priest. Beside this figure there is what may be "a human head with hair tied in a bun", resting on a stool. Behind this a large horned animal, usually agreed to be a ram, perhaps with a human head, completes the top tier of the images.[17]

In a lower tier, seven more or less identical figures, shown in a line in right-facing profile (on the seal, so left-facing on impressions), wear plumed headdresses, bangles, and dresses falling to around knee-level. What seems to be their hair is tied in a braid and comes down to waist level. Their gender is unclear, though they are often thought to be female. Groups of seven figures are seen in other pieces,[18] and a number of IVC seals show a variety of trees, that may have a religious significance, and do so in later Hinduism — banyan, pipal, and acacia.[19]

2.3. Swastika Seals

IVC Swastikas were prim. engraved in button (and square) seals.[20] Manabu Koiso and other scholars classify the signs as "geometric motifs"[21]; these types became extremely predominant at the end of the Mature Harappan Phase and the relative sizing of these seals might have reflected socio-economic, political, and religious hierarchy.[20][22][23] E. C. L. During Caspers found the Swastika Seals to have served "mercantile purposes" in certain trade routes; Gregory Possehl has separately documented relevant trade-circulation.[24] Kenoyer notes the IVC Swastika to be an abstract "decorative motif" that might have reflected contemporary ideology; he also posits a possible usage in trade — the seals either denoted the owners involved in a commercial transaction or were proto-bureaucratic certifications.[19]

Overall, the precise purpose of these seals in IVC continue to remain inconclusive but it is unlikely that they served any religio-ritualistic purpose.[22] Also, Swastika had developed in multiple cultures of the world contemporaneous to or even pre-dating IVC. That Swastika has been recorded in early Andronovo culture, the roots of Hindu Swastika might easily lie in the Indo-Aryan migrations.[25]

3. Sculptures

3.1. Terracotta Figurines: Mother Goddess

Certain terracotta statuettes have been identified as figurines of "Mother Goddess" (and fertility, by extension) by a spectrum of scholars — Ernest J. H. Mackay, Marshall, Walter Fairservis, Bridget Allchin, Hiltebeitel,[26] Jim G. Shaffer, and Parpola[27] among others — thus positing links to the Shakti tradition in Hinduism.[28][29] Recent scholarship reject such identification and links.[29][30]

Scholars like David Kinsley and Lynn Foulston accept the figurine-identifications, but rejects that there is any conclusive evidence to link them with Shaktism.[31][32] Sree Padma, in an anthropological study of the Grāmadevatā tradition, finds pre-Hindu roots but declines to explicitly identify it with IVC.[33] Kenower remains ambiguous — the figurines might have been worshipers or deities — and does not mention of any links with Shaktism.[19] Yuko Yukochi, in her "landmark publication" on Shaktism,[34] refuses to discuss IVC influences — the undeciphered script did not allow integrating the archeological with the literary.[35]

Peter Ucko had challenged the very identification as early as 1967 but failed to make any noticeable dent.[29] In the last three decades, the identification has been increasingly rejected by a newer generation of scholars — Sharri Clark, Ardeleanu-Jansen, Ajay Pratap, P.V. Pathak, and others.[29][30] In 2007, Gregory Possehl found the evidence in favor of such an identification to be "not particularly robust"; he further writes, "".[11] Shereen Ratnagar (2016) rejects the identification, as being based on flimsy evidence.[28] As does Doniger.[27] Clark, in what has been described as a ground-breaking work on terracotta figurines of Harappa,[36] emphatically rejects that there exists any bases for the Mother Goddess identification or hypothesizing a continuance into Hinduism.[37]

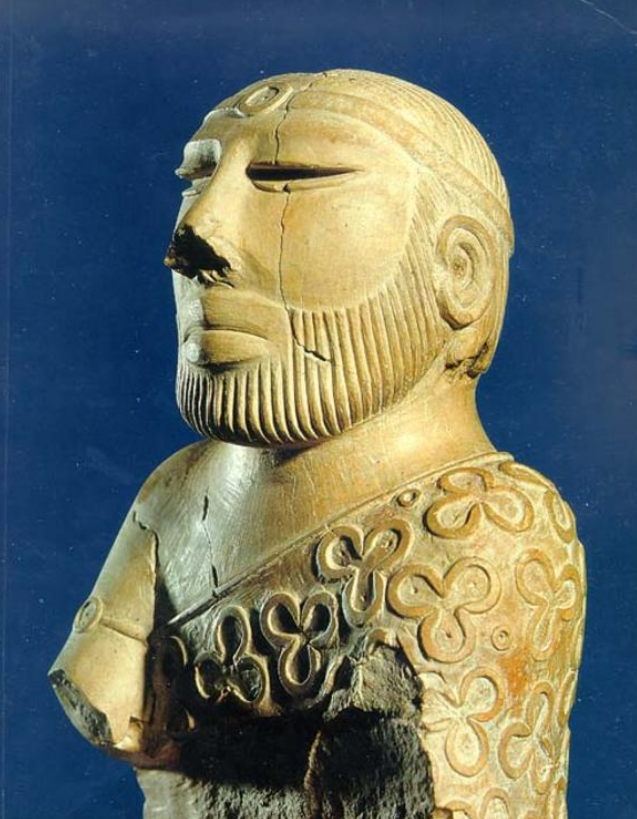

3.2. Priest King

- Mackay, the archaeologist leading the excavations at the site when the piece was found, thought the statuette might represent a "priest".[38] John Marshall agreed and regarded it as possibly a "king-priest", but it appears to have been his successor, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who was the first to use the designation of Priest-King in support of his proposition that the urban complexities had to necessarily result from a ruling class.[38][39][40][41] One of the "seven principal pieces of human sculpture from Mohenjo-daro",[42] Parpola has even hypothesized that it resembles later Indian traditions of priesthood.[43]

The terminology is not preferred in modern scholarship[44] and scholars have increasingly shifted to the view that IVC was a far egalitarian society with some kind of clan rule.[39][40][45][46] Modern scholars find the term as well as the hypothesis to be highly speculative, problematic, and "without foundation" — Wendy Doniger in a scathing review noted that Parpola's "desire and imagination" surpassed available evidence.[27][47][48][49] The statuette is now believed by many to be the result of interactions with the culture to the north, the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex, around the Oxus river.[40][50]

3.3. Miscellaneous

A broken stone sculpture — after reconstruction of missing limbs — has been proposed to assume a dancer's pose, thus being evocative of Nataraja.[6] Another broken clay figurine has female breasts and male genitals, bearing some similarities with Ardhanarishvara.[6]

4. Architecture

4.1. Buildings

Kenower notes that certain large structures might have been used as temples but their precise function cannot be determined; Possehl asserts there is a total absence of temples.[11][19] Hiltebeitel and a few other scholars suggest that the elevated citadel complex might have served sacred functions — Possehl rejected such arguments.[11][26]

4.2. Stones

Yonis

Marshall proposed certain ovular limestone stones to be the symbolic representation of yonis, thus drawing links to the cult of phallic worship in Hinduism.[7][51] Mackay, in his summary reports, rejected Marshall's view: they were architectural stones, probably from a stone pillar.[7][51] Despite, Marshall's hypothesis went on to propagate in mainstream scholarship notwithstanding multiple critiques.[26] Modern scholars have come to largely reject the hypothesis.[52]

George F. Dales chose to outright reject the hypothesis about sexual aspects in Harappan religion — If such stones served cultic functions, they would be spread over all Harappan sites and Marshall's findings were untenable on an overall review of excavation finds — and Srinivasan as well as Asko Parpola agreed with his specific rebuts; yet in light of other evidence, Parpola cautioned against ruling out Marshall's broader hypothesis in totality.[7][53] Later excavations have since vindicated Mackay's assumptions.[52][54] Dilip Chakrabarti continue to support Marshall's identification.[55]

Lingams

To a similar effect, Marshall argued certain cone/dome-shaped stone-pieces to be abstract representations of lingams, as seen in modern-day Hinduism.[7] Despite significant critiques, Marshall's view had propagated into scholarship.[7]

H. D. Sankalia rejected these identifications, too; he raised the issue of these stones being typically found in streets and drains, which ought not house objects with a sacred connotation.[7] Srinivasan rejected Marshall's arguments, as well: (a) the more old a Linga was, the more realistic (and non-abstract) was its appearance thus contradicting presentation expected from Harappan era, and (b) the sculpts of ancient lingams are found in the Brahminical heartland of India but not in IVC/post-IVC sites.[7]

4.3. Great Bath: Water and Cleanliness

Some scholars, deriving from Marshall, propose the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro to be a forerunner of ritual bathing, central to Hinduism.[26][26][54] Doniger rejects the hypotheses; to her, the Great Bath is only suggestive of Harappans having a propensity for water/bath.[27] Possehl finds Marshall's theory of a ritual purpose to be convincing.[11]

Elaborate sewage networks suggest to Hiltebeitel and Parpola an excessive concern with personal cleanliness, which is correlated to the development of caste-pollution theories in Hinduism.[26][27]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Religion_of_the_Indus_Valley_Civilization

References

- Wright 2009, p. 1.

- Wright: "Mesopotamia and Egypt ... co-existed with the Indus civilization during its florescence between 2600 and 1900 BC."[15]

- Wright 2009.

- Wright: "The Indus civilisation is one of three in the 'Ancient East' that, along with Mesopotamia and Pharaonic Egypt, was a cradle of early civilisation in the Old World (Childe, 1950). Mesopotamia and Egypt were longer-lived, but coexisted with Indus civilisation during its florescence between 2600 and 1900 B.C. Of the three, the Indus was the most expansive, extending from today’s northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and India."[16]

- Giosan et al. 2012.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1975). "The So-Called Proto-śiva Seal from Mohenjo-Daro: An Iconological Assessment". Archives of Asian Art 29: 47–58. ISSN 0066-6637. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20062578.

- Srinivasan, Doris (1984). "Unhinging Śiva from the Indus Civilization". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1): 77–89. ISSN 0035-869X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25211627.

- Flood 1996, pp. 28–29.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (1978). "The Indus Valley "Proto-Śiva", Reexamined through Reflections on the Goddess, the Buffalo, and the Symbolism of vāhanas". Anthropos 73 (5/6): 767–797. ISSN 0257-9774. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40459645.

- Mahishasura is a Sanskrit word composed of Mahisha meaning buffalo and asura meaning demon, thus meaning Buffalo Demon. Mahishasura had gained the boon that no man could kill him. In the battles between the Devas and the demons (asuras), the Devas, led by Indra, were defeated by Mahishasura. Subjected to defeat, the Devas assembled in the mountains where their combined divine energies coalesced into Goddess Durga. The newborn Durga led a battle against Mahishasura, riding a lion, and killed him. Thereafter, she was named Mahishasuramardini, meaning The Killer of Mahishasura.[21]

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2007), Hinnells, John R., ed., "The Indus Civilization", A Handbook of Ancient Religions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): pp. 418–489, ISBN 978-1-107-80484-5

- Samuel, Geoffrey, ed. (2008), "Introduction", The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): pp. 1–14, ISBN 978-0-521-87351-2, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/origins-of-yoga-and-tantra/introduction/AC8EFB094BC7E06B1ABAE4682F80E660, retrieved 2021-08-09

- Geer, Alexandra Van Der (2008). "Rhinoceros Unicornis". Animals in Stone : Indian Mammals Sculptured Through Time. Brill. pp. 384. ISBN 9789004168190.

- Doniger, Wendy (2011). "God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva". Social Research 78 (2): 485–508. ISSN 0037-783X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23347187.

- Witzel 2008, pp. 68–70, 90.

- Witzel: "It is known from internal evidence that the Vedic texts were orally composed in northern India, at first in the Greater Punjab and later on also in more eastern areas, including northern Bihar, between ca. 1500 BCE and ca. 500–400 BCE. The oldest text, the Rgveda, must have been more or less contemporary with the Mitanni texts of northern Syria/Iraq (1450–1350 BCE); ..." (p. 70) "a Vedic connection of the so-called Siva Pasupati found on some Harappa seals (D. Srinivasan 1984) cannot be established; this mythological concept is due, rather, to common Eurasian ideas of the “Lord of the Animals” who is already worshipped by many Neolithic hunting societies."[25]

- Aruz, 403; Harappa.com, with good photo; Possehl (2002), 145-146 https://www.harappa.com/indus/34.html

- Aruz, 403; Possehl (2002), 145-146

- Kenower, Jonathan Mark (2006). "Cultures and Societies of the Indus Tradition". in Thapar, Romila. Historical Roots in the Making of the 'Aryan'. National Book Trust.

- Parpola, Asko (2018), Jamison, Gregg; Ameri, Marta; Scott, Sarah Jarmer et al., eds., "Indus Seals and Glyptic Studies: An Overview", Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): pp. 127–143, doi:10.1017/9781108160186.011, ISBN 978-1-107-19458-8, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/seals-and-sealing-in-the-ancient-world/indus-seals-and-glyptic-studies-an-overview/C98636E09557C57E6F2D92A52EC45447, retrieved 2021-08-09

- Other "geometric motifs" include concentric circles, knots, and stars.

- Avari, Burjor (2007). "The Harappan Civilisation". India: The Ancient Past : A History of the Indian Sub-Continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200. Routledge. pp. 49. ISBN 9780415356152.

- Konasukawa, Ayumu; Koiso, Manabu (2018). "The Size of Indus Seals and its Significance". Walking with the Unicorn: Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer Felicitation Volume. ArchaeoPress. ISBN 9781784919184.

- Caspers, Elisabeth C.L. During (1973). "HARAPPAN TRADE IN THE ARABIAN GULF IN THE THIRD MILLENNIUM B.C.". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 3: 3–20. ISSN 0308-8421. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41223270.

- Kuz’Mina, E. E.; Mallory, J. P. (2007-01-01). "Ceramics" (in en). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. p. 73. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789047420712/Bej.9789004160545.i-763_006.xml.

- Hiltebeitel 1989.

- Doniger, Wendy (2017-08-02). "Another Great Story" (in en). Inference: International Review of Science 3 (2). doi:10.37282/991819.17.40. https://inference-review.com/article/another-great-story.

- Ratnagar, Shereen (2016-12-01). "A critical view of Marshall’s Mother Goddess at Mohenjo-Daro" (in en). Studies in People's History 3 (2): 113–127. doi:10.1177/2348448916665714. ISSN 2348-4489. https://doi.org/10.1177/2348448916665714.

- Bhardwaj, Deeksha (18 October 2018). "Traces of the Past: The Terracotta Repertoire From the Harappan Civilisation". https://www.sahapedia.org/traces-of-the-past-the-terracotta-repertoire-the-harappan-civilisation.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (2007). "Gender and Archaeology in South and Southwest Asia". in Nelson, Sarah M.. Worlds of Gender: The Archaeology of Women's Lives Around the Globe. Rowman Altamira. pp. 79. ISBN 9780759110847.

- Foulston, p. 4.

- Kinsley(a), p. 217.

- Padma, Sree (17 October 2013). Vicissitudes of the Goddess : Reconstructions of the Gramadevata in India's Religious Traditions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199325030.

- Sarkar, Bihani (2019-05-29), "Durgā" (in en), Hinduism (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/obo/9780195399318-0219, ISBN 978-0-19-539931-8, http://oxfordbibliographiesonline.com/view/document/obo-9780195399318/obo-9780195399318-0219.xml, retrieved 2021-08-10

- Yuokochi, Yuko (2004). The Rise of the Warrior-Goddess in Ancient India: A Study of the Myth of Kauśikī-Vindhyavāsinī in the Skanda-Purāṇa (Thesis). University of Groningen. p. 7-8.

- Fritz, John M. (June 2019). "Review of "The Social Lives of Figurines: Reconstructing the Third-Millennium-BC Terracotta Figurines from Harappa. Sharri R. Clark. Cambridge, MA: Papers of the Peabody Museum 86, 2017, 362 pp. + CD. $85.00, paper. ISBN 9780873652155."". Journal of Anthropological Research 75 (2): 269–270. doi:10.1086/702805. ISSN 0091-7710. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/702805.

- Clark, Sharri R. (20 February 2017). The Social Lives of Figurines: Recontextualizing the Third-Millennium-BC Terracotta Figurines from Harappa. Papers of the Peabody Museum: 86. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780873652155.

- Possehl, 115

- Coningham & Young 2015, pp. 480–83a.

- Green, Adam S. (2021-06-01). "Killing the Priest-King: Addressing Egalitarianism in the Indus Civilization" (in en). Journal of Archaeological Research 29 (2): 153–202. doi:10.1007/s10814-020-09147-9. ISSN 1573-7756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-020-09147-9.

- The absence of palatial structures meant that typical kings were not a good fit. So, the idea of a military-theocratic state was borrowed from Mesopotamia.

- Possehl, 113

- Parpola 2015.

- For an example, see Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund referring to the statuette as "so-called Priest King" in the latest edition of their classic introductory text for undergraduates, A History of India.

- Wright 2009, p. 252.

- Possehl, 57; Green; Singh (2008), 176-179; Matthiae and Lamberg-Karlovsky, 377

- Possehl, 115 (quoted); Aruz, 385; Singh (2008), 178

- McKay, A. C.; Parpola, Asko (2017). "Review of The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, ParpolaAsko". Asian Ethnology 76 (2): 431–434. ISSN 1882-6865. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017682.

- Kenoyer 2014, p. 424,b "The most famous of these stone figures was originally referred to as the “Priest-King” (Fig. 1.25.8) based on similar images from Mesopotamia, but there is no way to confirm this identification without the aid of written texts."

- Vidale, Massimo (2017). "Contacts with other regions and the Indus". Treasures from the Oxus: The Art and Civilization of Central Asia. Bloomsbury. pp. 56. ISBN 9781784537722.

- Asko Parpola (1985). "The Sky Garment - A study of the Harappan religion and its relation to the Mesopotamian and later Indian religions". Studia Orientalia (The Finnish Oriental Society) 57: 101–107.

- Vidale, Massimo (2010-04-19). "Aspects of Palace Life at Mohenjo-Daro". South Asian Studies 26 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1080/02666031003737232. ISSN 0266-6030. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666031003737232.

- Asko Parpola (1985). "The Sky Garment - A study of the Harappan religion and its relation to the Mesopotamian and later Indian religions". Studia Orientalia (The Finnish Oriental Society) 57: 101–107.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008) (in en). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. pp. 277. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- Lipner, Julius J. (2017) (in en). Hindu Images and Their Worship with Special Reference to Vaisnavism: A Philosophical-theological Inquiry. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 39. ISBN 9781351967822. OCLC 985345208. https://books.google.com/books?id=yDAlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA39.