The gastropods (/ˈɡæstrəpɒdz/), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda (/ɡæsˈtrɒpədə/). This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from the land. There are many thousands of species of sea snails and slugs, as well as freshwater snails, freshwater limpets, and land snails and slugs. The class Gastropoda contains a vast total of named species, second only to the insects in overall number. The fossil history of this class goes back to the Late Cambrian. (As of 2017), 721 families of gastropods are known, of which 245 are extinct and appear only in the fossil record, while 476 are currently extant with or without a fossil record. Gastropoda (previously known as univalves and sometimes spelled "Gasteropoda") are a major part of the phylum Mollusca, and are the most highly diversified class in the phylum, with 65,000 to 80,000 living snail and slug species. The anatomy, behavior, feeding, and reproductive adaptations of gastropods vary significantly from one clade or group to another, so stating many generalities for all gastropods is difficult. The class Gastropoda has an extraordinary diversification of habitats. Representatives live in gardens, woodland, deserts, and on mountains; in small ditches, great rivers, and lakes; in estuaries, mudflats, the rocky intertidal, the sandy subtidal, the abyssal depths of the oceans, including the hydrothermal vents, and numerous other ecological niches, including parasitic ones. Although the name "snail" can be, and often is, applied to all the members of this class, commonly this word means only those species with an external shell big enough that the soft parts can withdraw completely into it. Those gastropods without a shell, and those with only a very reduced or internal shell, are usually known as slugs; those with a shell into which they can partly but not completely withdraw are termed semislugs. The marine shelled species of gastropods include species such as abalone, conches, periwinkles, whelks, and numerous other sea snails that produce seashells that are coiled in the adult stage—though in some, the coiling may not be very visible, for example in cowries. In a number of families of species, such as all the various limpets, the shell is coiled only in the larval stage, and is a simple conical structure after that.

- abyssal

- reproductive adaptations

- intertidal

1. Etymology

In the scientific literature, gastropods were described as "gasteropodes" by Georges Cuvier in 1795.[1] The word gastropod comes from Greek γαστήρ (gastḗr 'stomach') and πούς (poús 'foot'), a reference to the fact that the animal's "foot" is positioned below its guts.[2]

The earlier name "univalve" means one valve (or shell), in contrast to bivalves, such as clams, which have two valves or shells.

2. Diversity

At all taxonomic levels, gastropods are second only to the insects in terms of their diversity.[3]

Gastropods have the greatest numbers of named mollusc species. However, estimates of the total number of gastropod species vary widely, depending on cited sources. The number of gastropod species can be ascertained from estimates of the number of described species of Mollusca with accepted names: about 85,000 (minimum 50,000, maximum 120,000).[4] But an estimate of the total number of Mollusca, including undescribed species, is about 240,000 species.[5] The estimate of 85,000 molluscs includes 24,000 described species of terrestrial gastropods.[4]

Different estimates for aquatic gastropods (based on different sources) give about 30,000 species of marine gastropods, and about 5,000 species of freshwater and brackish gastropods. Many deep-sea species remain to be discovered, as only 0.0001% of the deep-sea floor has been studied biologically.[6][7] The total number of living species of freshwater snails is about 4,000.[8]

Recently extinct species of gastropods (extinct since 1500) number 444, 18 species are now extinct in the wild (but still exist in captivity), and 69 species are "possibly extinct".[9]

The number of prehistoric (fossil) species of gastropods is at least 15,000 species.[10]

In marine habitats, the continental slope and the continental rise are home to the highest diversity, while the continental shelf and abyssal depths have a low diversity of marine gastropods.[11]

3. Habitat

Some of the more familiar and better-known gastropods are terrestrial gastropods (the land snails and slugs). Some live in fresh water, but most named species of gastropods live in a marine environment.

Gastropods have a worldwide distribution, from the near Arctic and Antarctic zones to the tropics. They have become adapted to almost every kind of existence on earth, having colonized nearly every available medium.

In habitats where not enough calcium carbonate is available to build a really solid shell, such as on some acidic soils on land, various species of slugs occur, and also some snails with thin, translucent shells, mostly or entirely composed of the protein conchiolin.

Snails such as Sphincterochila boissieri and Xerocrassa seetzeni have adapted to desert conditions. Other snails have adapted to an existence in ditches, near deepwater hydrothermal vents, the pounding surf of rocky shores, caves, and many other diverse areas.

Gastropods can be accidentally transferred from one habitat to another by other animals, e.g. by birds.[12]

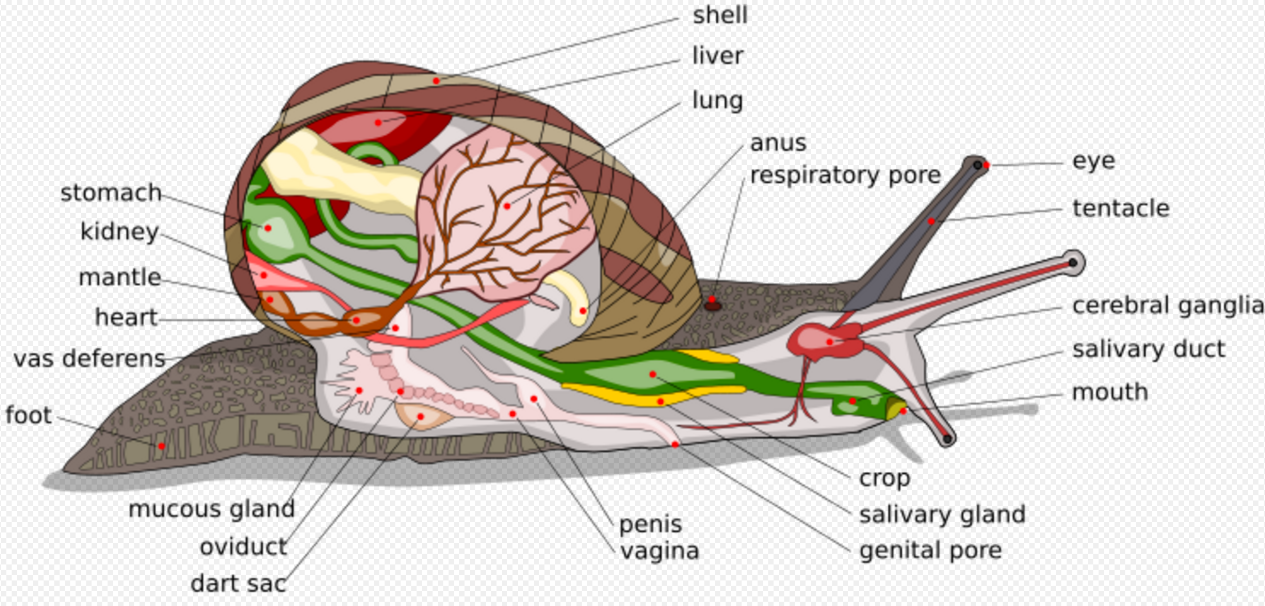

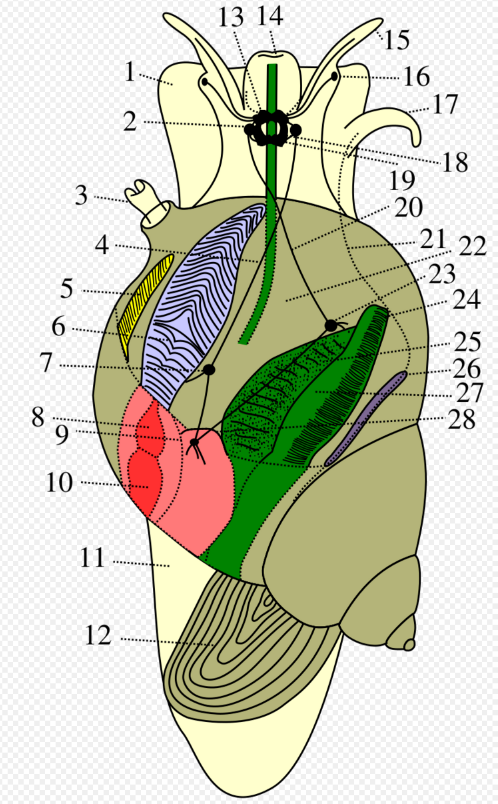

4. Anatomy

- Light yellow - body

- Brown - shell and operculum

- Green - digestive system

- Light purple - gills

- Yellow - osphradium

- Red - heart

- Pink -

- Dark violet -

- foot

- cerebral ganglion

- pneumostome

- upper commissure

- osphradium

- gills

- pleural ganglion

- atrium of heart

- visceral ganglion

- ventricle

- foot

- operculum

- brain

- mouth

- tentacle (chemosensory, 2 or 4)

- eye

- penis (everted, normally internal)

- esophageal nerve ring

- pedal ganglion

- lower commissura

- vas deferens

- pallial cavity / mantle cavity / respiratory cavity

- parietal ganglion

- anus

- hepatopancreas

- gonad

- rectum

- nephridium

Snails are distinguished by an anatomical process known as torsion, where the visceral mass of the animal rotates 180° to one side during development, such that the anus is situated more or less above the head. This process is unrelated to the coiling of the shell, which is a separate phenomenon. Torsion is present in all gastropods, but the opisthobranch gastropods are secondarily untorted to various degrees.[13][14]

Torsion occurs in two stages. The first, mechanistic stage, is muscular, and the second is mutagenetic. The effects of torsion are primarily physiological; the organism develops an asymmetrical growth, with the majority occurring on the left side. This leads to the loss of right-paired appendages (e.g., ctenidia (comb-like respiratory apparatus), gonads, nephridia, etc.). Furthermore, the anus becomes redirected to the same space as the head. This is speculated to have some evolutionary function, as prior to torsion, when retracting into the shell, first the posterior end would get pulled in, and then the anterior. Now, the front can be retracted more easily, perhaps suggesting a defensive purpose.

However, this "rotation hypothesis" is being challenged by the "asymmetry hypothesis" in which the gastropod mantle cavity originated from one side only of a bilateral set of mantle cavities.[15]

Gastropods typically have a well-defined head with two or four sensory tentacles with eyes, and a ventral foot, which gives them their name (Greek gaster, stomach, and pous, foot). The foremost division of the foot is called the propodium. Its function is to push away sediment as the snail crawls. The larval shell of a gastropod is called a protoconch.

The principal characteristic of the Gastropoda is the asymmetry of their principal organs. The essential feature of this asymmetry is that the anus generally lies to one side of the median plane.; The ctenidium (gill-combs), the osphradium (olfactory organs), the hypobranchial gland (or pallial mucous gland), and the auricle of the heart are single or at least are more developed on one side of the body than the other; Furthermore, there is only one genital orifice, which lies on the same side of the body as the anus.[16]

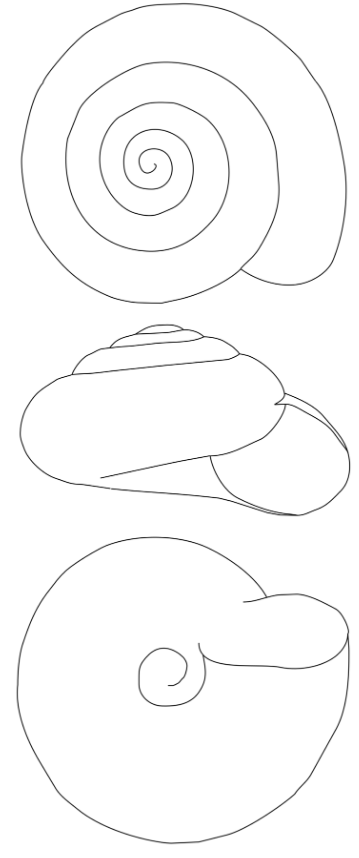

4.1. Shell

Most shelled gastropods have a one piece shell (with exceptional bivalved gastropods), typically coiled or spiraled, at least in the larval stage. This coiled shell usually opens on the right-hand side (as viewed with the shell apex pointing upward). Numerous species have an operculum, which in many species acts as a trapdoor to close the shell. This is usually made of a horn-like material, but in some molluscs it is calcareous. In the land slugs, the shell is reduced or absent, and the body is streamlined.

Some gastropods have adult shells which are bottom heavy due to the presence of a thick, often broad, convex ventral callus deposit on the inner lip and adapical to the aperture which may be important for gravitational stability.[17]

4.2. Body Wall

Some sea slugs are very brightly colored. This serves either as a warning, when they are poisonous or contain stinging cells, or to camouflage them on the brightly colored hydroids, sponges and seaweeds on which many of the species are found.

Lateral outgrowths on the body of nudibranchs are called cerata. These contain an outpocketing of digestive gland called the diverticula.

4.3. Sensory Organs and Nervous System

The sensory organs of gastropods include olfactory organs, eyes, statocysts and mechanoreceptors.[18] Gastropods have no hearing.[18]

In terrestrial gastropods (land snails and slugs), the olfactory organs, located on the tips of the four tentacles, are the most important sensory organ.[18] The chemosensory organs of opisthobranch marine gastropods are called rhinophores.

The majority of gastropods have simple visual organs, eye spots either at the tip or base of the tentacles. However, "eyes" in gastropods range from simple ocelli that only distinguish light and dark, to more complex pit eyes, and even to lens eyes.[19] In land snails and slugs, vision is not the most important sense, because they are mainly nocturnal animals.[18]

The nervous system of gastropods includes the peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system. The central nervous system consist of ganglia connected by nerve cells. It includes paired ganglia: the cerebral ganglia, pedal ganglia, osphradial ganglia, pleural ganglia, parietal ganglia and the visceral ganglia. There are sometimes also buccal ganglia.[18]

4.4. Digestive System

The radula of a gastropod is usually adapted to the food that a species eats. The simplest gastropods are the limpets and abalones, herbivores that use their hard radula to rasp at seaweeds on rocks.

Many marine gastropods are burrowers, and have a siphon that extends out from the mantle edge. Sometimes the shell has a siphonal canal to accommodate this structure. A siphon enables the animal to draw water into their mantle cavity and over the gill. They use the siphon primarily to "taste" the water to detect prey from a distance. Gastropods with siphons tend to be either predators or scavengers.

4.5. Respiratory System

Almost all marine gastropods breathe with a gill, but many freshwater species, and the majority of terrestrial species, have a pallial lung. The respiratory protein in almost all gastropods is hemocyanin, but one freshwater pulmonate family, the Planorbidae, have hemoglobin as the respiratory protein.

In one large group of sea slugs, the gills are arranged as a rosette of feathery plumes on their backs, which gives rise to their other name, nudibranchs. Some nudibranchs have smooth or warty backs with no visible gill mechanism, such that respiration may likely take place directly through the skin.

4.6. Circulatory System

Gastropods have open circulatory system and the transport fluid is hemolymph. Hemocyanin is present in the hemolymph as the respiratory pigment.

4.7. Excretory System

The primary organs of excretion in gastropods are nephridia, which produce either ammonia or uric acid as a waste product. The nephridium also plays an important role in maintaining water balance in freshwater and terrestrial species. Additional organs of excretion, at least in some species, include pericardial glands in the body cavity, and digestive glands opening into the stomach.

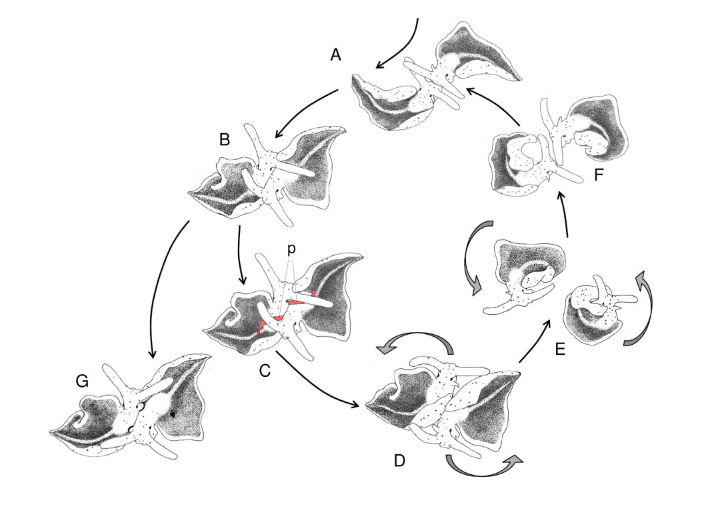

4.8. Reproductive System

Courtship is a part of mating behavior in some gastropods, including some of the Helicidae. Again, in some land snails, an unusual feature of the reproductive system of gastropods is the presence and utilization of love darts.

In many marine gastropods other than the opisthobranchs, there are separate sexes (dioecious/gonochoric); most land gastropods, however, are hermaphrodites.

5. Life Cycle

Courtship is a part of the behavior of mating gastropods with some pulmonate families of land snails creating and utilizing love darts, the throwing of which have been identified as a form of sexual selection.[20]

The main aspects of the life cycle of gastropods include:

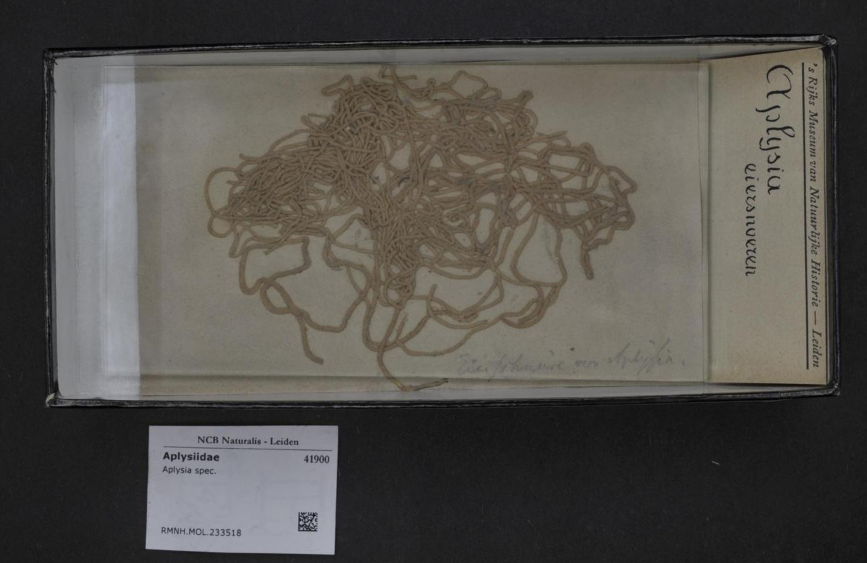

- Egg laying and the eggs of gastropods

- The embryonic development of gastropods

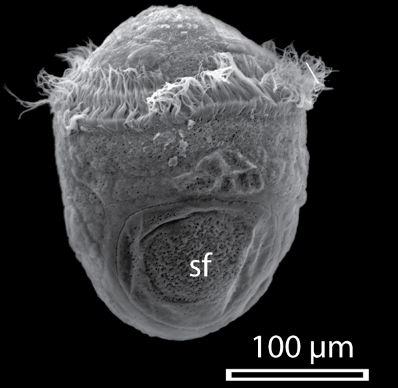

- The larvae or larval stadium: some gastropods may be trochophore and/or veliger

- Estivation and hibernation (each of these are present in some gastropods only)

- The growth of gastropods

- Courtship and mating in gastropods: fertilization is internal or external according to the species. External fertilization is common in marine gastropods.

6. Feeding Behavior

thumb|A Pomacea maculata'' floating and eating a carrot

The diet of gastropods differs according to the group considered. Marine gastropods include some that are herbivores, detritus feeders, predatory carnivores, scavengers, parasites, and also a few ciliary feeders, in which the radula is reduced or absent. Land-dwelling species can chew up leaves, bark, fruit and decomposing animals while marine species can scrape algae off the rocks on the seafloor. Certain species such as the Archaeogastropda maintain horizontal rows of slender marginal teeth. In some species that have evolved into endoparasites, such as the eulimid Thyonicola doglieli, many of the standard gastropod features are strongly reduced or absent.

A few sea slugs are herbivores and some are carnivores. The carnivorous habit is due to specialisation. Many gastropods have distinct dietary preferences and regularly occur in close association with their food species.

Some predatory carnivorous gastropods include, for example: Cone shells, Testacella, Daudebardia, Ghost slug and others.

7. Genetics

Gastropods exhibit an important degree of variation in mitochondrial gene organization when compared to other animals.[21] Main events of gene rearrangement occurred at the origin of Patellogastropoda and Heterobranchia, whereas fewer changes occurred between the ancestors of Vetigastropoda (only tRNAs D, C and N) and Caenogastropoda (a large single inversion, and translocations of the tRNAs D and N).[21] Within Heterobranchia, gene order seems relatively conserved, and gene rearrangements are mostly related with transposition of tRNA genes.[21]

8. Geological History and Evolution

The first gastropods were exclusively marine, with the earliest representatives of the group appearing in the Late Cambrian (Chippewaella, Strepsodiscus),[22] though their only gastropod character is a coiled shell, so they could lie in the stem lineage, if they are gastropods at all.[23] Earliest Cambrian organisms like Helcionella, Barskovia and Scenella are no longer considered gastropods, and the tiny coiled Aldanella of earliest Cambrian time is probably not even a mollusk.

As such, it's not until the Ordovician that the first crown-group members arise.[24] By the Ordovician period the gastropods were a varied group present in a range of aquatic habitats. Commonly, fossil gastropods from the rocks of the early Palaeozoic era are too poorly preserved for accurate identification. Still, the Silurian genus Poleumita contains fifteen identified species. Fossil gastropods were less common during the Palaeozoic era than bivalves.[24]

Most of the gastropods of the Palaeozoic era belong to primitive groups, a few of which still survive. By the Carboniferous period many of the shapes seen in living gastropods can be matched in the fossil record, but despite these similarities in appearance the majority of these older forms are not directly related to living forms. It was during the Mesozoic era that the ancestors of many of the living gastropods evolved.[24]

One of the earliest known terrestrial (land-dwelling) gastropods is Anthracopupa (=Maturipupa),[25] which is found in the Coal Measures of the Carboniferous period in Europe, but relatives of the modern land snails are rare before the Cretaceous period, when the familiar Helix first appeared.[24]

In rocks of the Mesozoic era, gastropods are slightly more common as fossils; their shells are often well preserved. Their fossils occur in ancient beds deposited in both freshwater and marine environments. The "Purbeck Marble" of the Jurassic period and the "Sussex Marble" of the early Cretaceous period, which both occur in southern England, are limestones containing the tightly packed remains of the pond snail Viviparus.[24]

Rocks of the Cenozoic era yield very large numbers of gastropod fossils, many of these fossils being closely related to modern living forms. The diversity of the gastropods increased markedly at the beginning of this era, along with that of the bivalves.[24]

Certain trail-like markings preserved in ancient sedimentary rocks are thought to have been made by gastropods crawling over the soft mud and sand. Although these trace fossils are of debatable origin, some of them do resemble the trails made by living gastropods today.[24]

Gastropod fossils may sometimes be confused with ammonites or other shelled cephalopods. An example of this is Bellerophon from the limestones of the Carboniferous period in Europe, the shell of which is planispirally coiled and can be mistaken for the shell of a cephalopod.

Gastropods are one of the groups that record the changes in fauna caused by the advance and retreat of the Ice Sheets during the Pleistocene epoch.

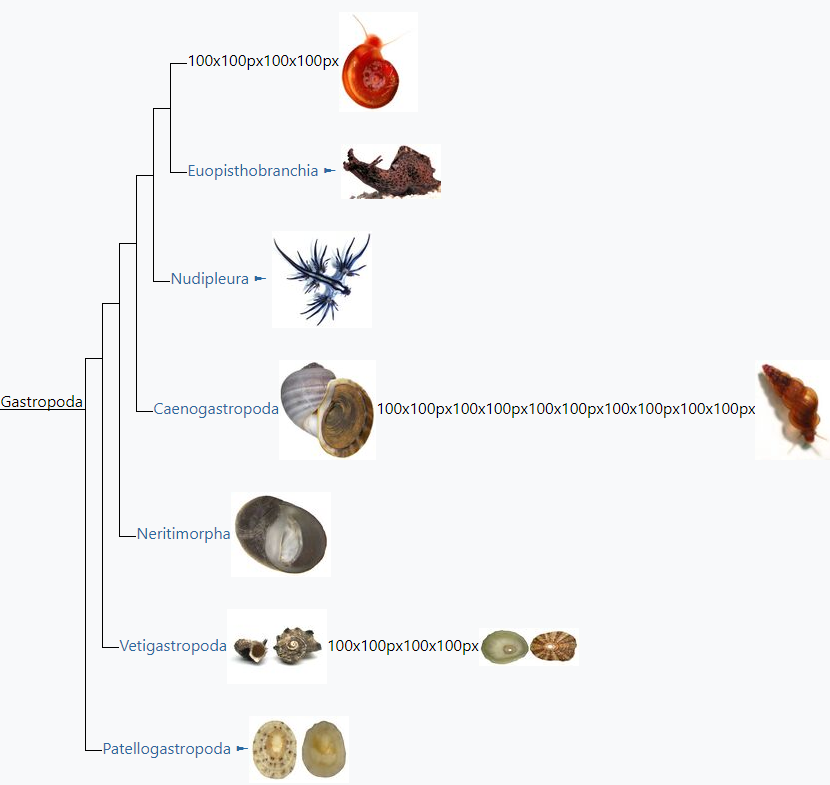

Cladogram

A cladogram showing the phylogenic relationships of Gastropoda with example species:[26]

9. Taxonomy

Since Darwin, biological taxonomy has attempted to reflect the phylogeny of organisms, i.e., the tree of life. The classifications used in taxonomy attempt to represent the precise interrelatedness of the various taxa. However, the taxonomy of the Gastropoda is constantly being revised and so the versions shown in various texts can differ in major ways.

In the older classification of the gastropods, there were four subclasses:[27]

- Opisthobranchia (gills to the right and behind the heart).

- Gymnomorpha (no shell)

- Prosobranchia (gills in front of the heart).

- Pulmonata (with a lung instead of gills)

The taxonomy of the Gastropoda is still under revision, and more and more of the old taxonomy is being abandoned, as the results of DNA studies slowly become clearer. Nevertheless, a few of the older terms such as "opisthobranch" and "prosobranch" are still sometimes used in a descriptive way.

New insights based on DNA sequencing of gastropods have produced some revolutionary new taxonomic insights. In the case of the Gastropoda, the taxonomy is now gradually being rewritten to embody strictly monophyletic groups (only one lineage of gastropods in each group). Integrating new findings into a working taxonomy remain challenging. Consistent ranks within the taxonomy at the level of subclass, superorder, order, and suborder have already been abandoned as unworkable. Ongoing revisions of the higher taxonomic levels are expected in the near future.

Convergent evolution, which appears to exist at especially high frequency in gastropods, may account for the observed differences between the older phylogenies, which were based on morphological data, and more recent gene-sequencing studies.

Bouchet & Rocroi (2005)[28][29] made sweeping changes in the systematics, resulting in a taxonomy that is a step closer to the evolutionary history of the phylum. The Bouchet & Rocroi classification system is based partly on the older systems of classification, and partly on new cladistic research.

In the past, the taxonomy of gastropods was largely based on phenetic morphological characters of the taxa. The recent advances are more based on molecular characters from DNA[30] and RNA research. This has made the taxonomical ranks and their hierarchy controversial. The debate about these issues is not likely to end soon.

In the Bouchet, Rocroi et al. taxonomy, the authors have used unranked clades for taxa above the rank of superfamily (replacing the ranks suborder, order, superorder and subclass), while using the traditional Linnaean approach for all taxa below the rank of superfamily. Whenever monophyly has not been tested, or is known to be paraphyletic or polyphyletic, the term "group" or "informal group" has been used. The classification of families into subfamilies is often not well resolved, and should be regarded as the best possible hypothesis.

In 2004, Brian Simison and David R. Lindberg showed possible diphyletic origins of the Gastropoda based on mitochondrial gene order and amino acid sequence analyses of complete genes.[31]

In the 2017 issue of the Malacologia journal (available online from 4 January 2018), a significantly updated version of the 2005 "Bouchet & Rocroi" taxonomy was published in the paper "Revised Classification, Nomenclator and Typification of Gastropod and Monoplacophoran Families".[32]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:Gastropoda

References

- Cuvier, G (1795). "Second mémoire sur l'organisation et les rapports des animaux à sang blanc, dans lequel on traite de la structure des Mollusques et de leur division en ordres, lu à la Société d'histoire naturelle de Paris, le 11 Prairial, an III" (in fr). Magazin Encyclopédique, ou Journal des Sciences, des Lettres et des Arts 2: 433–449. Archived from the original on 2017-07-25. https://web.archive.org/web/20170725031628/https://archive.org/stream/magazinencyclop12pari#page/448/mode/1up.

- "Gastropod". https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=gastropod.

- McArthur, A.G.; M.G. Harasewych (2003). "Molecular systematics of the major lineages of the Gastropoda.". Molecular Systematics and Phylogeography of Mollusks. Washington: Smithsonian Books. pp. 140–160.

- Chapman, A.D. (2009). Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World, 2nd edition . Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra. Accessed 12 January 2010. ISBN:978-0-642-56860-1 (printed); ISBN:978-0-642-56861-8 (online). http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/abrs/publications/other/species-numbers/2009/04-02-groups-invertebrates.html#mollusca

- Appeltans W., Bouchet P., Boxshall G.A., Fauchald K., Gordon D.P., Hoeksema B.W., Poore G.C.B., van Soest R.W.M., Stöhr S., Walter T.C., Costello M.J. (eds) (2011). World Register of Marine Species. Accessed at marinespecies.org on 2011-03-07. http://www.marinespecies.org

- "Census of Marine Life (2012). SYNDEEP: Towards a first global synthesis of biodiversity, biogeography and ecosystem function in the deep sea. Unpublished data (datasetID: 59)". http://www.comlsecretariat.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/SYNDEEP-Towards-a-first-global-synthesis-of-biodiversity-biogeography-and-ecosystem-function-in-the-deep-sea-Eva-Ramirez-Llodra-et-al..pdf.

- "gastropod" . (2010). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 05, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/226777/gastropod

- Strong, Ellen E.; Gargominy, Olivier; Ponder, Winston F.; Bouchet, Philippe (January 2008). "Global diversity of gastropods (Gastropoda; Mollusca) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia 595: 149–166. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9012-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10750-007-9012-6

- Régnier, C.; Fontaine, B. T.; Bouchet, P. (October 2009). "Not Knowing, Not Recording, Not Listing: Numerous Unnoticed Mollusk Extinctions". Conservation Biology 23 (5): 1214–1221. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01245.x. PMID 19459894. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1523-1739.2009.01245.x

- (in Spanish) Nájera J. M. (1996). "Moluscos del suelo como plagas agrícolas y cuarentenarias". X Congreso Nacional Agronómico / II Congreso de Suelos 1996 51-56. PDF http://www.bio-nica.info/biblioteca/Monje1996.pdf

- Rex, Michael A. (1973-09-14). "Deep-Sea Species Diversity: Decreased Gastropod Diversity at Abyssal Depths" (in en). Science 181 (4104): 1051–1053. doi:10.1126/science.181.4104.1051. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17731267. Bibcode: 1973Sci...181.1051R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.181.4104.1051

- RUSIECKI S. & RUSIECKA A. 2013. Hairy snail Trochulus hispidus (Linnaeus, 1758) in flight - a note on avian dispersal of snails. Folia Malacologica 21(2):111-112. http://www.foliamalacologica.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=402&catid=114&Itemid=146

- Kay, A.; Wells, F. E.; Poder, W. F. (1998). "Class Gastropoda". in Beesley, P. L.. Mollusca: The Southern Synthesis. Fauna of Australia. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 565–604. ISBN 978-0-643-05756-2.

- null

- Louise R. Page (April 2006). "Modern insights on gastropod development: Reevaluation of the evolution of a novel body plan". Integrative and Comparative Biology 46 (2): 134–143. doi:10.1093/icb/icj018. PMID 21672730. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Ficb%2Ficj018

- Suter, Henry. Manual of the New Zealand mollusca /. J. Mackay, govt. printer. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/16786. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- Geerat J. Vermeij (2022). "The balanced life: evolution of ventral shell weighting in gastropods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 194 (1): 256–275. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlab019. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlab019.

- Chase R.: Sensory Organs and the Nervous System. in Barker G. M. (ed.): The biology of terrestrial molluscs. CABI Publishing, Oxon, UK, 2001, ISBN:0-85199-318-4. 1-146, cited pages: 179–211.

- Götting, Klaus-Jürgen (1994). "Schnecken". in Becker, U.. Lexikon der Biologie. Heidelberg: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86025-156-0.

- Koene, Joris M. (August 1, 2006). "Tales of two snails: sexual selection and sexual conflict in Lymnaea stagnalis and Helix aspersa". Integrative and Comparative Biology 46 (4): 419–429. doi:10.1093/icb/icj040. PMID 21672754. https://academic.oup.com/icb/article/46/4/419/633995. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- Cunha, R. L.; Grande, C.; Zardoya, R. (2009). "Neogastropod phylogenetic relationships based on entire mitochondrial genomes". BMC Evolutionary Biology 9: 210. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-210. PMID 19698157. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2741453

- Yochelson, Ellis L.; Nuelle, Laurence M. (1985). "Strepsodiscus (Gastropoda) in the Late Cambrian of Missouri". Journal of Paleontology 59 (3): 733–740.

- Budd, G. E., and S. Jensen. 2000: A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla. Biological Reviews 75:253–295.

- Be'Norr, K., and J. FnÍon (1999). "Notes on the evolution and higher classification of the subclass Neritimorpha (Gastropoda) with the description of some new taxa". Geol. Et Palaeont 33: 219–235. http://www.paleoliste.de/bandel/bandel_1999d.pdf. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Jochum, Adrienne; Yu, Tingting; Neubauer, Thomas A. (2020). "First record of the Paleozoic land snail family Anthracopupidae in the Lower Jurassic of China and the origin of Stylommatophora" (in en). Journal of Paleontology 94 (2): 266–272. doi:10.1017/jpa.2019.68. ISSN 0022-3360. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-paleontology/article/abs/first-record-of-the-paleozoic-land-snail-family-anthracopupidae-in-the-lower-jurassic-of-china-and-the-origin-of-stylommatophora/294B5CB18D294A34BF7D814D1FD68701.

- Kenny, Nathan J.; Truchado-García, Marta; Grande, Cristina (2016). "Deep, multi-stage transcriptome of the schistosomiasis vector Biomphalaria glabrata provides platform for understanding molluscan disease-related pathways". BMC Infectious Diseases 16 (1): 618. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1944-x. ISSN 1471-2334. PMID 27793108. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5084317

- Paul Jeffery.Suprageneric classification of class Gastropoda. The Natural History Museum, London, 2001.

- Bouchet P. & Rocroi J.-P. (Ed.); Frýda J., Hausdorf B., Ponder W., Valdes A. & Warén A. 2005. Classification and nomenclator of gastropod families. Malacologia: International Journal of Malacology, 47(1-2). ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany. ISBN:3-925919-72-4. 397 pp. vliz.be http://www.vliz.be/Vmdcdata/imis2/ref.php?refid=78278

- Poppe G.T. & Tagaro S.P. 2006. The new classification of Gastropods according to Bouchet & Rocroi, 2005. Visaya, février 2006: 10 pp. journal-malaco.fr http://www.journal-malaco.fr/bouchet&rocroi_2005_Visaya.pdf

- Elpidio A. Remigio; Paul D.N. Hebert (2003). "Testing the utility of partial COI sequences for phylogenetic (full text on line)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 29 (3): 641–647. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00140-4. PMID 14615199. http://www.bolinfonet.org/pdf/MPEVsnailpaper.pdf.

- "Unitas malacologica, Newsletter number 21 december 2004 - a .pdf file". http://www.ucd.ie/cobid/unitas/newsletter/UMNewsletter_21.pdf.

- Philippe Bouchet, Jean-Pierre Rocroi, Bernhard Hausdorf, Andrzej Kaim, Yasunori Kano, Alexander Nützel, Pavel Parkhaev, Michael Schrödl and Ellen E. Strong. 2017. Revised Classification, Nomenclator and Typification of Gastropod and Monoplacophoran Families. Malacologia, 61(1-2): 1-526. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.4002/040.061.0201?journalCode=mala