Sürdürülebilir kalkınma hedefleri (SDG'ler), 2015'te kabul edilen 17 hedefi içeren, BM'nin herkes için daha iyi ve daha sürdürülebilir bir gelecek elde etme planının küresel bir kalkınma programıdır. Yoksulluk, eşitsizlik, iklim değişikliği dahil olmak üzere küresel nüfusun karşılaştığı zorlukları ele alırlar. , çevresel bozulma, barış ve adalet. Programlar genellikle sürdürülebilir ekonomik büyümeyi ve sürdürülebilir kalkınma için 2030 gündemini uygulamak için sürdürülebilirliğin güçlendirilmesi modlarını vurgular. Bu SDG'lerden SDGS 7, 8, 9, 11, 12 ve 17, doğrudan ve/veya dolaylı olarak sürdürülebilirlik ve döngüsellik fenomeniyle bağlantılıdır. Birleşmiş Milletler'in (BM) SKH'lerine imza atan ülkelerdeki hükümetler, ulusal politika ve programlar da dahil olmak üzere farklı eylemlerde bulunarak hedefe ulaşılmasında çok önemli bir rol oynamaktadır,

- sustainability

- circular economy

- sustainable development

- SDGs

1. Sustainable Development through Circular Economy (CE) Strategies and Practices

2. SDGs Status and Current Global Trends

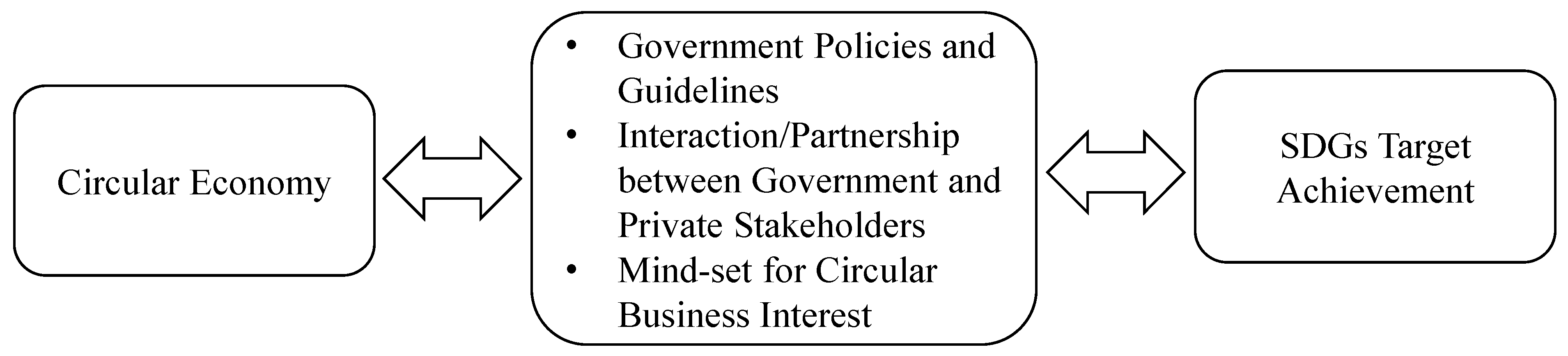

3. Conceptual Framework of Circular Economy for SDGs

The position of communities in the development process can be defined to a significant extent by sociocultural, environmental, and economic indicators. Undoubtedly, the initial phase of the social and economic development of humanity was dominated by rural and agricultural production. Considering the climate change projections, the risks posed by global climate change entail measures for increasing production and productivity in the face of population growth as well as the development of novel technologies and production systems based on adaptation to increases in temperature [https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/84351]. In this framework, R&D and technology policies and research and extension (R&E) policies need to be highlighted.

Sharing status of CE-related technology

It should be noted right away that; Technologies to be used for CE should be the common property of humanity. This may be a new paradigm, but the main thing is the future of the earth, the continuity of sustainable life. As is known, worldwide experience shows that new technologies have been the driver of social and economic development. “Cumulative Adoption of Technology” refers to the sum of all countries. Generally speaking, countries compete to take, use and utilize the technology by their own means (locally) or under the influence of international scientific research. Naturally, countries’ ability to produce technology and adoption of innovations lead to faster utilization of the positive effects of such technologies, but not all countries have the capacity to develop and transfer from outside and uphold the technologies they need [https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/84351]. Therefore, it is necessary to define a new approach in which the technologies produced for climate change are considered, in a sense, the “common property of humanity” for countries that are unable to produce or transfer technology and have no means to compete with others. It is a fact that the creation of such a culture of sharing will serve all of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals set forth by the UN. So, in order to reduce the effects of climate change, which is a global threat to the earth, it will be important that the UN develops a mechanism that will ensure the exchange of existing and new technologies to be developed among countries, regardless of their ability to produce technology. (Source:Özçatalbaş, O. (2022). An Evaluation of the Transition from Linear Economy to Circular Economy. In (Ed.), Sustainable Rural Development [Working Title]. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.107980 )

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su132011455

References

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimon, F. A systematic literature review. relationships between the sharing economy, sustainability and sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744.

- General Assembly and ECOSOC Joint Meeting. Circular Economy for the SDGs: From Concept to Practice. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ga/second/73/jm_conceptnote.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Alaimo, L.S.; Ciacci, A.; Ivaldi, E. Measuring sustainable development by non-aggregative approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 157, 101–122.

- United Nations. Take Action for Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Jennifer, R. Using case studies in research. Manag. Res. News 2002, 25, 16–27.

- Bachtrögler, J.; Fratesi, U.; Perucca, G. The influence of circular economy of the local context on the implementation and impact of EU cohesion policy. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 21–34.

- Investopedia. 2020 Predictions for the Global Economy and Markets. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/2020-predictions-for-the-global-economy-markets-and-investors-4780156 (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Fortuna, S.; Martineillo, L.; Morea, D. The strategic role of the corporate social responsibility and cercular economy in the cosmetic industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5120.

- Dias, M.A.; Loureiro, F.B. A systemic approach to sustainability—The interconnection of its dimensions in ecovillage practices. Ambiente Soc. 2019, 22, 1–18.

- Jawahir, I.S.; Bradley, R. Technological elements of circular economy and the principles of 6r-based closed-loop material flow in sustainable manufacturing. Procedia Cirp 2016, 40, 103–108.

- Grdic, Z.S.; Nizic, M.K.; Rudan, E. Circular economy concept in the context of economic development in EU countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3060.

- Ramani, S.V. Moving Away from the “Linear Economy Model” towards a “Circular Economy”. Available online: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/print/moving-away-from-the-linear-economy-model-towards-a-circular-economy-1518187431 (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. What is a Circular Economy? A Framework for an Economy that is Restorative and Regenerative by Design. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Winkler, H. Closed-loop production systems—A sustainable supply chain approach. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 243–246.

- Bocken, N.M.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320.

- Mestre, A.; Cooper, T. Circular product design. A multiple loops life cycle design approach for the circular economy. The Des. J. 2017, 20, 1620–1635.

- Evian. Packaging and Recycling. Available online: https://www.evian.com/en_us/sustainable-bottled-water/water-bottle-recycling-and-packaging/ (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Inside FMCG. Evian Creates Label-Free Bottle in Circular Economy Move. Available online: https://insidefmcg.com.au/2020/08/04/evian-creates-label-free-bottle-in-circular-economy-move/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20new%20bottle%20is%20a,company%20said%20in%20a%20statement (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Apple Inc. Material Impact Profiles. Available online: https://www.apple.com/environment/pdf/Apple_Material_Impact_Profiles_April2019.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Islam, J.M. Bangladesh must Transition from Linear Economy to Circular Economy. The Business Standard. Available online: https://tbsnews.net/opinion/bangladesh-must-transition-linear-economy-circular-economy-42587 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Busu, M.; Trica, C.L. Sustainability of circular economy indicators and their impact on economic growth of the European Union. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5481.

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809.

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L. Towards an education for the circular economy (ECE): Five teaching principles and a case study, resources. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104406.

- Dagiliene, L.; Varaniut, V.; Bruneckiene, J. Local governments’ perspective on implementing the circular economy: A framework for future solutions. J. Clean. Prod 2021, 320, 127340.

- Blomsma, F.; Brennan, G. The Emergence of Circular Economy: A New Framing around Prolonging Resource Productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 603–614.

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M.; Kato, M.; Hengesbaugh, M.; Hotta, Y.; Aoki-Suzuki, C.; Gamaralalage, P.J.D.; Liu, C. Circular Economy and Plastics: A Gap-Analysis in ASEAN Member States; European Commission Directorate General for Environment and Directorate General for International Cooperation and Development: Brussels, Belgium; Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019.

- Climate-KIC. Municipality-Led Circular Economy Case Studies: In Partnership with the Climate-Kic Circular Cities Project. Available online: https://www.climate-kic.org/in-detail/municipality-circular-economy-case-studies/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Hiraishi, T.; Krug, T.; Tanabe, K.; Srivastava, N.; Baasansuren, J.; Fukuda, M.; Troxler, T.G. (Eds.) 2013 Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Esken, B.; Franco-García, M.L.; Fisscher, O.A.M. CSR perception as a signpost for circular economy. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 586–604.

- Islam, M.M.; Shamsuddoha, M. Coastal and marine conservation strategy for Bangladesh in the context of achieving blue growth and sustainable development goals (SDGs). Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 87, 45–54.

- Johnston, M.P. Secondary data analysis: A method of which the time has come. QQML 2017, 3, 619–626.

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, 3rd ed.; AltaMira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2002.

- Ahmed, K.J.; Haq, S.A.; Bartiaux, F. The nexus between extreme weather events, sexual violence, and early marriage: A study of vulnerable populations in Bangladesh. Popul. Environ. 2019, 40, 303–324.