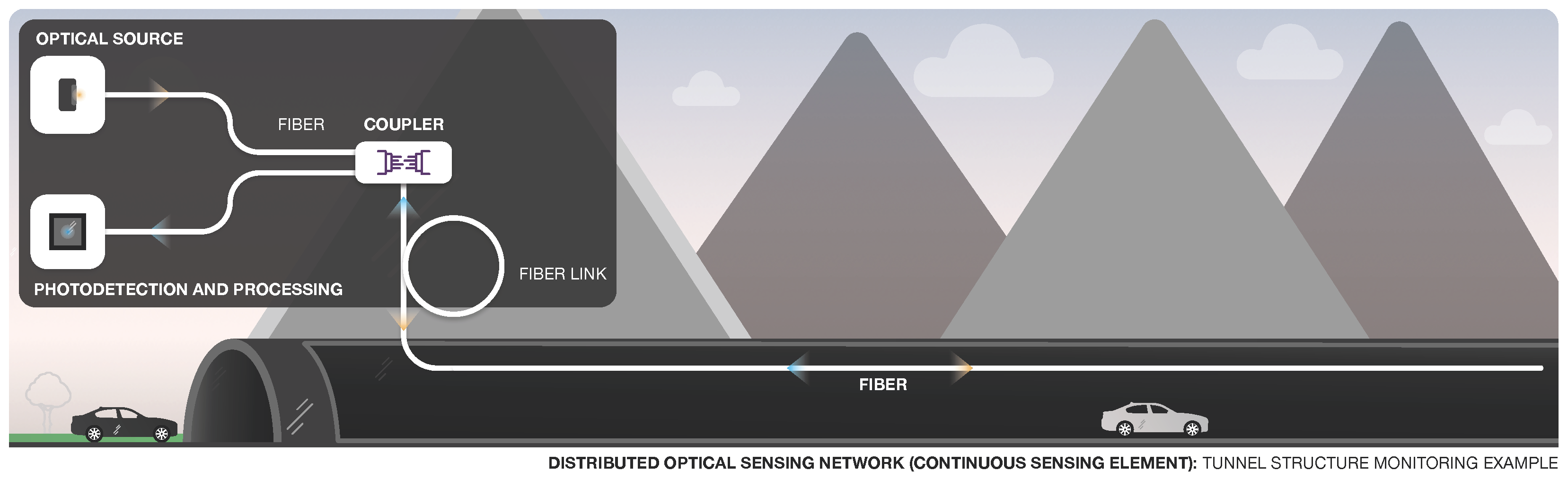

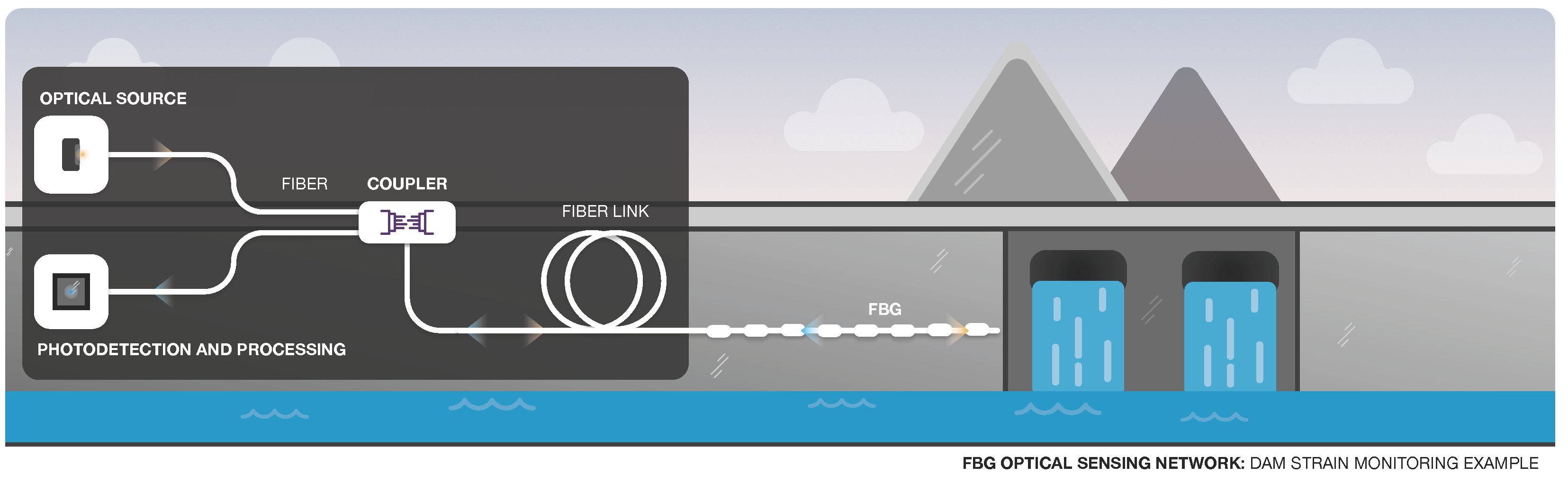

Optical fiber sensors present several advantages in relation to other types of sensors. These advantages are essentially related to the optical fiber properties, i.e., small, lightweight, resistant to high temperatures and pressure, electromagnetically passive, among others. Sensing is achieved by exploring the properties of light to obtain measurements of parameters, such as temperature, strain, or angular velocity. In addition, optical fiber sensors can be used to form an Optical Fiber Sensing Network (OFSN) allowing manufacturers to create versatile monitoring solutions with several applications, e.g., periodic monitoring along extensive distances (kilometers), in extreme or hazardous environments, inside structures and engines, in clothes, and for health monitoring and assistance.

- optical fiber sensors

- optical fiber sensing

- optical fiber sensing networks

- sensor networks

- wireless sensor networks

1. Introduction

2. Optical Fiber Sensors

-

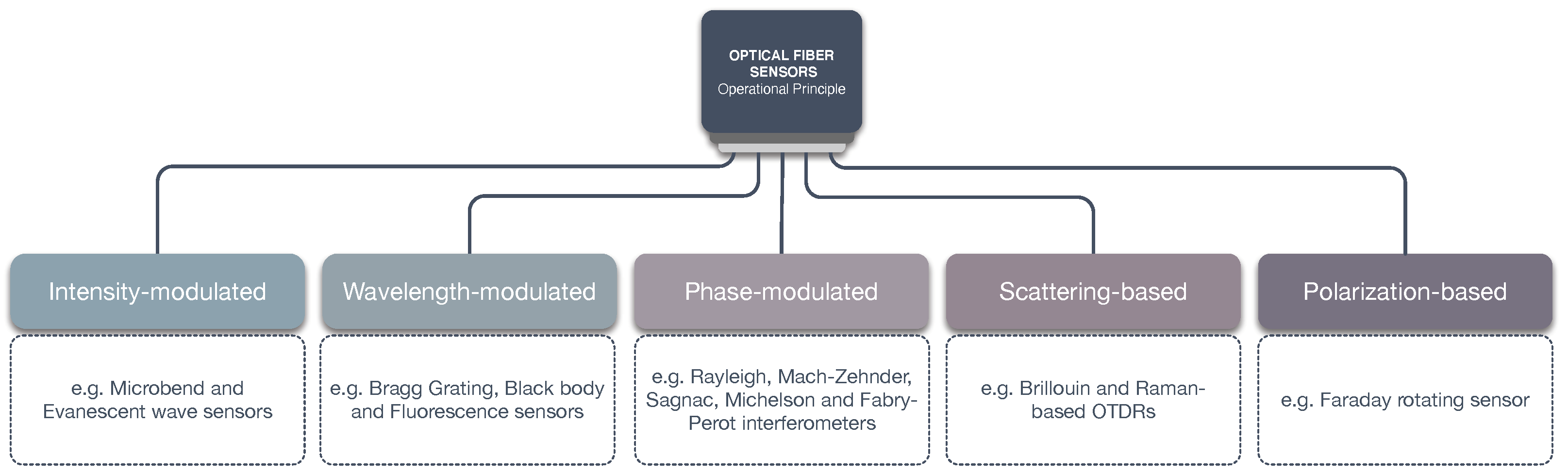

Intensity-modulated sensors were among the first optical fiber sensors to be developed [26]. These sensors can detect physical changes or perturbations in the received light (bend loss, attenuation, evanescent fields). Simplicity and lower costs present the advantages of this optical sensor type; however, these sensors are susceptible to fluctuations in optical power loss leading to false readings, and therefore requiring a reference system to minimize the problem.

-

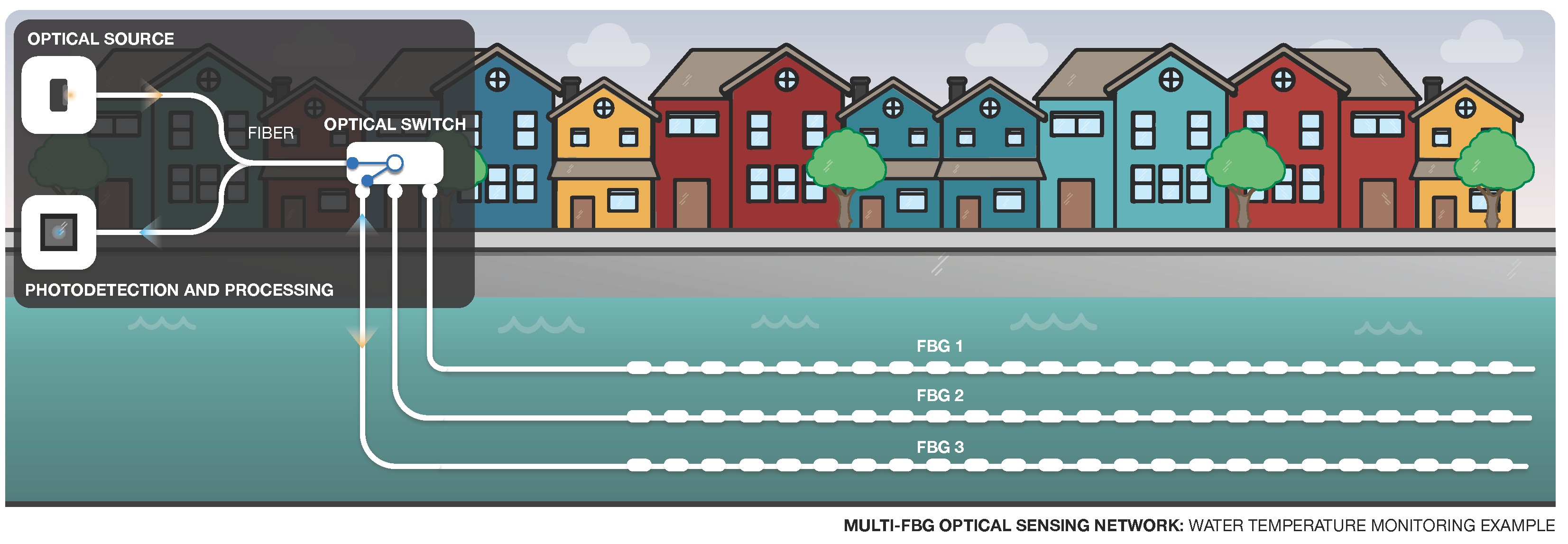

Wavelength-modulated sensors measure the wavelength change in the fiber. Examples of wavelength-modulated sensors include black body sensors, fluorescence sensors, and the Bragg grating wavelength-modulated sensors. The FBG sensor represents the most popular type of wavelength-modulated sensor and is frequently used in different applications since it is capable of single-point or multi-point sensing.

-

Phase-modulated sensors use the interferometry principle to measure interference of the optical fiber light. These sensors are popular owing to their high sensitivity and accuracy; however, this also translates to a higher cost. The most popular phase-modulated sensors include the Mach–Zehnder, Sagnac, Michelson, and Fabry–Perot interferometers.

-

Scattering-based sensors use an Optical Time Domain Reflectometer (OTDR) to detect changes in the scattered light. These sensors are very popular since they enable distributed sensing along the length of the fiber with interesting applications in structural health monitoring, and measuring changes in strain.

-

Polarization-based sensors detect changes in the light caused by an alteration in the polarization state. These sensors exploit the birefringence phenomenon in the optical fiber, where depending on the polarization the refractive index changes. When applying strain to the optical fiber, the birefringence effect occurs and results in a detectable phase difference.

3. Optical Fiber Sensing Networks

3.1. Multiplexing Techniques

3.2. Distributed Sensing

3.3. Multi-Point Sensing

3.4. OFSN Applications

-

Electric and magnetic fields: A summarized overview of fiber optic sensors for measuring electric and magnetic fields was proposed in [68], which are used in single point sensing configuration for localized measurements.

-

Localization of heat sources: Chirped FBGs have been used for localization of heat sources and shock wave detection, among other applications [69].

-

Battery management: A study to assess the possibility of integrating fiber optic sensors to monitor the battery health (temperature, strain, and humidity) was carried out in [70].

-

Healthcare: Heart rate and respiratory rate sensors based on FBGs perform multi-point sensing in [74]. A review of fiber optic sensors for sub-centimeter spatially resolved measurements [75] presented applications of these sensors in many areas, such as thermotherapy, catheterization for diagnostic purposes through gastroscopy, urology diagnostics, and smart textiles.

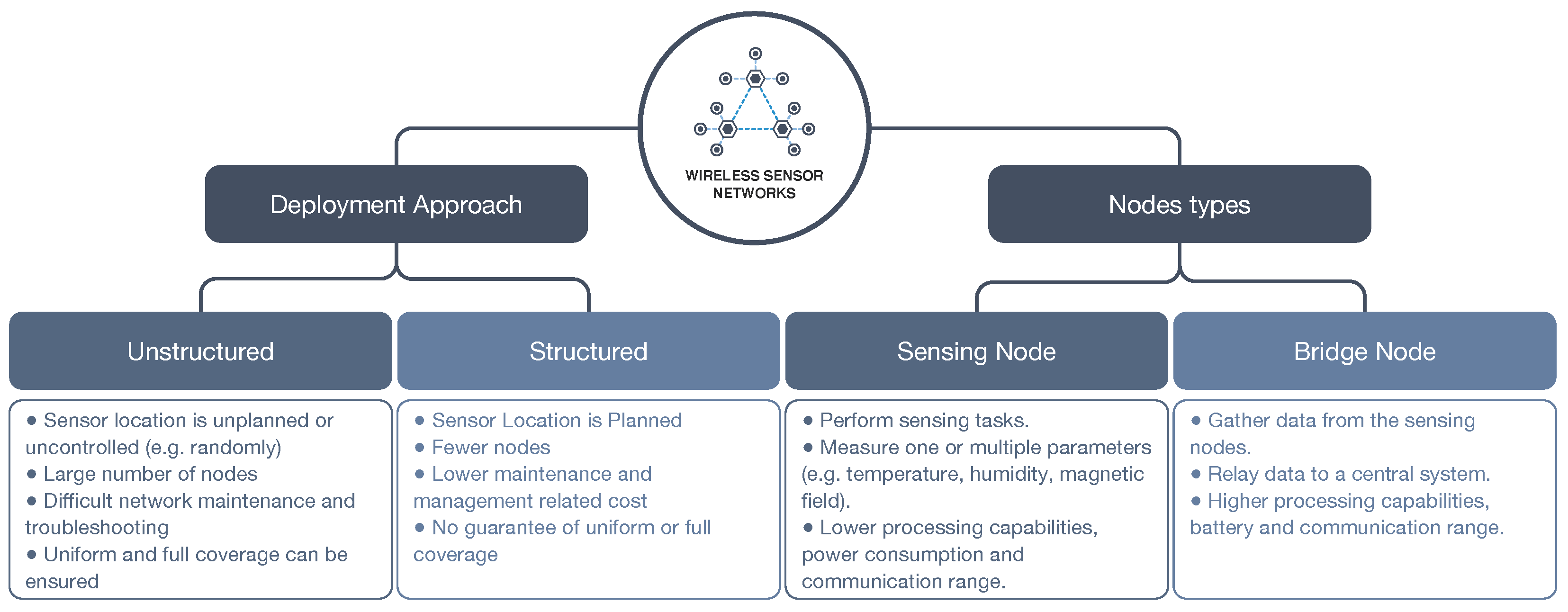

4. Wireless Sensor Networks

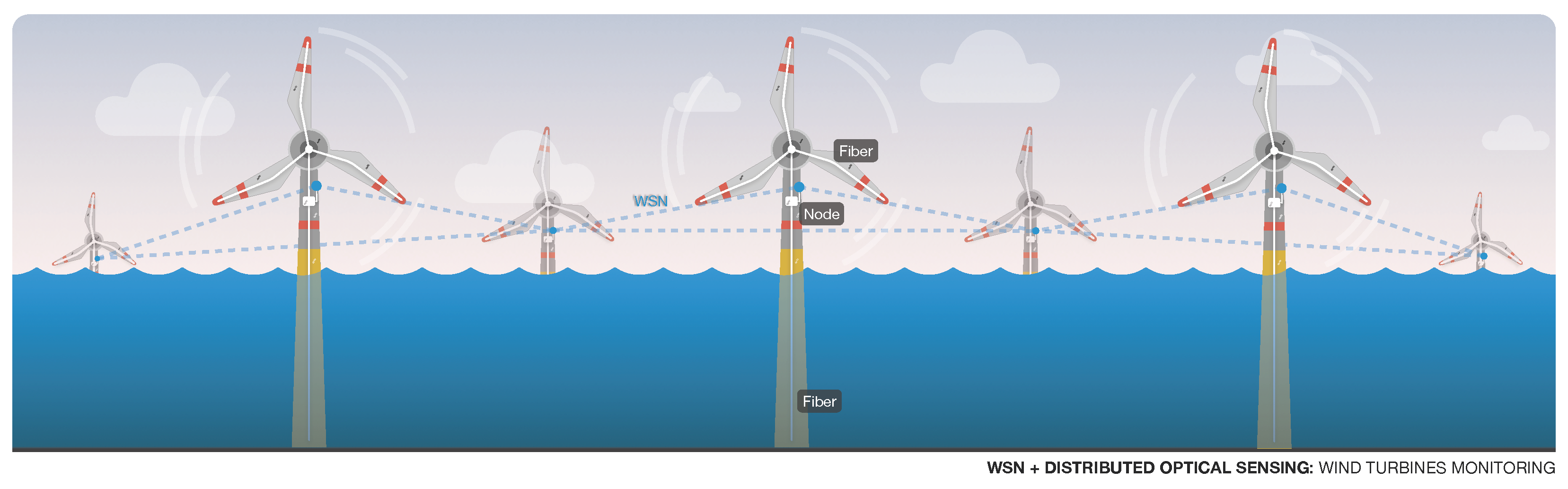

4.1. Integration with Optical Fiber Sensors

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/s22197554

References

- Kapron, F.P.; Keck, D.B.; Maurer, R.D. Radiation losses in glass optical waveguides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1970, 17, 423–425.

- Cordier, P.; Doukhan, J.C.; Fertein, E.; Bernage, P.; Niay, P.; Bayon, J.F.; Georges, T. TEM characterization of structural changes in glass associated to Bragg grating inscription in a germanosilicate optical fibre preform. Opt. Commun. 1994, 111, 269–275.

- Ishikawa, H. Ultrafast All-Optical Signal Processing Devices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008.

- Hill, K.O.; Fujii, Y.; Johnson, D.C.; Kawasaki, B.S. Photosensitivity in optical fiber waveguides: Application to reflection filter fabrication. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1978, 32, 647–649.

- Kurosawa, K.; Shirakawa, K.; Kikuchi, T. Development of Optical Fiber Current Sensors and Their Applications. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/PES Transmission & Distribution Conference & Exposition: Asia and Pacific, Dalian, China, 18 August 2005; pp. 1–6.

- Lin, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Liang, S. Review on Development and Applications of Fiber-Optic Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2012 Symposium on Photonics and Optoelectronics, Shanghai, China, 21–23 May 2012; pp. 1–4.

- Minakuchi, S.; Takeda, N. Recent advancement in optical fiber sensing for aerospace composite structures. Photonic Sens. 2013, 3, 345–354.

- Hegde, G.; Asokan, S.; Hegde, G. Fiber Bragg grating sensors for aerospace applications: A review. ISSS J. Micro Smart Syst. 2022, 11, 257–275.

- Wu, T.; Liu, G.; Fu, S.; Xing, F. Recent Progress of Fiber-Optic Sensors for the Structural Health Monitoring of Civil Infrastructure. Sensors 2020, 20, 4517.

- Wang, H.; Dai, J.G. Strain transfer analysis of fiber Bragg grating sensor assembled composite structures subjected to thermal loading. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 162, 303–313.

- Rajeev, P.; Kodikara, J.; Chiu, W.K.; Kuen, T. Distributed Optical Fibre Sensors and their Applications in Pipeline Monitoring. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 558, 424–434.

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.; Fu, Y.; Huang, S. A review of harsh environment fiber optic sensing networks for bridge structural health monitoring. Proc. SPIE 2006, 6314, 63140Y.

- Murayama, H.; Igawa, H.; Omichi, K.; Machijima, Y. Application of distributed sensing with long length FBG to structural health monitoring. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Optical Communications and Networks (ICOCN 2010), Nanjing, China, 24–27 October 2010; Volume 18, pp. 18–24.

- Afzal, M.H.B.; Kabir, S.; Sidek, O. Fiber optic sensor-based concrete structural health monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2011 Saudi International Electronics, Communications and Photonics Conference (SIECPC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 24–26 April 2011; pp. 1–5.

- Wild, G.; Allwood, G.; Hinckley, S. Distributed sensing, communications, and power in optical Fibre Smart Sensor networks for structural health monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2010 Sixth International Conference on Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information Processing, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 7–10 December 2010; pp. 139–144.

- Wang, D.Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Gong, J.; Wang, A. Fully distributed fiber-optic biological sensing. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2010, 22, 1553–1555.

- Goh, L.S.; Onodera, K.; Kanetsuna, M.; Watanabe, K.; Shinomiya, N. Constructing an optical fiber sensor network for natural environment remote monitoring. In Proceedings of the 17th Asia Pacific Conference on Communications, Sabah, Malaysia, 2–5 October 2011; pp. 208–212.

- Santos, J.L.; Frazãoa, O.; Baptista, J.M.; Jorge, P.A.; Dias, I.; Araújo, F.M.; Ferreira, L.A. Optical fibre sensing networks. In Proceedings of the 2009 SBMO/IEEE MTT-S International Microwave and Optoelectronics Conference (IMOC), Belem, Brazil, 3–6 November 2009; pp. 290–298.

- López-Higuera, J.M. Handbook of Optical Fibre Sensing Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002.

- Culshaw, B. Optical fiber sensor technologies: Opportunities and-perhaps-pitfalls. J. Light. Technol. 2004, 22, 39–50.

- Abe, N.; Arai, Y.; Nishiyama, M.; Shinomiya, N.; Watanabe, K.; Teshigawara, Y. A study on sensor multiplicity in optical fiber sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 24th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Perth, WA, Australia, 20–23 April 2010; pp. 519–525.

- Zhou, B.; Yang, S.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V. A novel wireless mobile platform integrated with optical fibre sensors. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Optical Fibre Sensors, Santander, Spain, 2–6 June 2014; López-Higuera, J.M., Jones, J.D.C., López-Amo, M., Santos, J.L., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9157, pp. 1317–1321.

- Ren, L.; Jiang, T.; Jia, Z.G.; Li, D.S.; Yuan, C.L.; Li, H.N. Pipeline corrosion and leakage monitoring based on the distributed optical fiber sensing technology. Measurement 2018, 122, 57–65.

- Fidanboylu, K.; Efendioglu, H. Fiber optic sensors and their applications. In Proceedings of the 5th International Advanced Technologies Symposium (IATS’09), Karabuk, Turkiye, 13–15 May 2009; Volume 6, pp. 2–3.

- N’cho, J.S.; Fofana, I. Review of Fiber Optic Diagnostic Techniques for Power Transformers. Energies 2020, 13, 1789.

- Choi, S.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Song, M.; Pan, J.K. A Self-Referencing Intensity-Based Fiber Optic Sensor with Multipoint Sensing Characteristics. Sensors 2014, 14, 12803–12815.

- Krohn, D.A.; MacDougall, T.; Mendez, A. Fiber Optic Sensors: Fundamentals and Applications; Spie Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014.

- Mittal, S.; Sharma, T.; Tiwari, M. Surface plasmon resonance based photonic crystal fiber biosensors: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 3071–3074.

- Marazuela, M.D.; Moreno-Bondi, M.C. Fiber-optic biosensors—An overview. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 372, 664–682.

- Bosch, M.E.; Sánchez, A.J.R.; Rojas, F.S.; Ojeda, C.B. Recent development in optical fiber biosensors. Sensors 2007, 7, 797–859.

- Leung, A.; Shankar, P.M.; Mutharasan, R. A review of fiber-optic biosensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 125, 688–703.

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.G.; Hu, S.; Peng, Y. Applications of fiber-optic biochemical sensor in microfluidic chips: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 166, 112447.

- De Acha, N.; Socorro-Leránoz, A.B.; Elosúa, C.; Matías, I.R. Trends in the Design of Intensity-Based Optical Fiber Biosensors (2010–2020). Biosensors 2021, 11, 197.

- Meng, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y. Recent Progress in Fiber-Optic Hydrophones. Photonic Sens. 2021, 11, 109–122.

- Lavrov, V.S.; Plotnikov, M.Y.; Aksarin, S.M.; Efimov, M.E.; Shulepov, V.A.; Kulikov, A.V.; Kireenkov, A.U. Experimental investigation of the thin fiber-optic hydrophone array based on fiber Bragg gratings. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2017, 34, 47–51.

- Plotnikov, M.Y.; Lavrov, V.S.; Dmitraschenko, P.Y.; Kulikov, A.V.; Meshkovskiy, I.K. Thin Cable Fiber-Optic Hydrophone Array for Passive Acoustic Surveillance Applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 3376–3382.

- Cole, J.H.; Kirkendall, C.; Dandridge, A. Twenty-five years of interferometric fiber optic acoustic sensors at the Naval Research Laboratory. J. Washingt. Acad. Sci. 2004, 90, 40–57.

- Peng, G.D.; Chu, P.L. Optical Fiber Hydrophone Systems, 2nd ed.; Optical Science and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; Chapter 9.

- Staudenraus, J.; Eisenmenger, W. Fibre-optic probe hydrophone for ultrasonic and shock-wave measurements in water. Ultrasonics 1993, 31, 267–273.

- Morris, P.; Hurrell, A.; Shaw, A.; Zhang, E.; Beard, P. A Fabry–Pérot fiber-optic ultrasonic hydrophone for the simultaneous measurement of temperature and acoustic pressure. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 125, 3611–3622.

- Webb, D.J.; Surowiec, J.; Sweeney, M.; Jackson, D.A.; Gavrilov, L.; Hand, J.; Zhang, L.; Bennion, I. Miniature fiber optic ultrasonic probe. In Proceedings of the Fiber Optic and Laser Sensors XIV, International Society for Optics and Photonics, Denver, CO, USA, 4–9 August 1996; Volume 2839, pp. 76–80.

- Wen, H.; Wiesler, D.G.; Tveten, A.; Danver, B.; Dandridge, A. High-sensitivity fiber-optic ultrasound sensors for medical imaging applications. Ultrason. Imaging 1998, 20, 103–112.

- Zakirov, R.; Umarov, A. Fiber optic gyroscope and accelerometer application in aircraft inertial system. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Science and Communications Technologies (ICISCT), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 4–6 November 2020; pp. 1–3.

- Imamura, T.; Matsui, T.; Yachi, M.; Kumagai, H. A low-cost interferometric fiber optic gyro for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2019), Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 1685–1695.

- Bremer, K.; Lewis, E.; Leen, G.; Moss, B.; Lochmann, S.; Mueller, I.; Reinsch, T.; Schroetter, J. Fibre optic pressure and temperature sensor for geothermal wells. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Sensors, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 1–4 November 2010; pp. 538–541.

- Islam, M.R.; Ali, M.M.; Lai, M.H.; Lim, K.S.; Ahmad, H. Chronology of Fabry-Perot Interferometer Fiber-Optic Sensors and Their Applications: A Review. Sensors 2014, 14, 7451–7488.

- Lobo Ribeiro, A. Esquemas de Multiplexagem de Sensores de Fibra Óptica. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal, 1996.

- Malakzadeh, A.; Pashaie, R.; Mansoursamaei, M. 150 km φ-OTDR sensor based on erbium and Raman amplifiers. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2020, 52, 326.

- Thévenaz, L.; Facchini, M.; Fellay, A.; Robert, P.; Inaudi, D.; Dardel, B. Monitoring of large structure using distributed Brillouin fibre sensing. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Kyongju, Korea, 12–16 April 1999; pp. 345–348.

- Adachi, S. Distributed optical fiber sensors and their applications. In Proceedings of the 2008 SICE Annual Conference, Chofu, Japan, 20–22 August 2008; pp. 329–333.

- Giallorenzi, T.G.; Bucaro, J.a.; Dandridge, A.; Sigel, G.H.; Cole, J.H.; Rkshleigh, S.; Priest, R.G. Optical Fiber Sensor Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981; Volume 2, pp. 626–665.

- Hartog, A.H. An Introduction to Distributed Optical Fibre Sensors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017.

- Kersey, A.D.; Davis, M.A.; Patrick, H.J.; LeBlanc, M.; Koo, K.P.; Askins, C.G.; Putnam, M.A.; Friebele, E.J. Fiber grating sensors. J. Light. Technol. 1997, 15, 1442–1462.

- Hill, K.O.; Meltz, G. Fiber Bragg grating technology fundamentals and overview. J. Light. Technol. 1997, 15, 1263–1276.

- Perez-Herrera, R.A.; Fernandez-Vallejo, M.; Lopez-Amo, M. Robust fiber-optic sensor networks. Photonic Sens. 2012, 2, 366–380.

- Diaz, S.; Abad, S.; Lopez-Amo, M. Fiber-optic sensor active networking with distributed erbium-doped fiber and Raman amplification. Laser Photonics Rev. 2008, 2, 480–497.

- Rodrigues, C.; Félix, C.; Figueiras, J. Monitorização Estrutural de Pontes com Sistemas em Fibra Ótica—Três Exemplos em Portugal. In Proceedings of the ASCP 2013 Segurança Conservação de Pontes, Porto, Portugal, 26–28 June 2013.

- Zhang, N.; Chen, W.; Zheng, X.; Hu, W.; Gao, M. Optical sensor for steel corrosion monitoring based on etched fiber bragg grating sputtered with iron film. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 3551–3556.

- Banerji, P.; Chikermane, S.; Grattan, K.; Tong, S.; Surre, F.; Scott, R. Application of fiber-optic strain sensors for monitoring of a pre-stressed concrete box girder bridge. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE SENSORS Proceedings, Limerick, Ireland, 28–31 October 2011; pp. 1345–1348.

- Lanticq, V.; Gabet, R.; Taillade, F.; Delepine-Lesoille, S. Distributed Optical Fibre Sensors for Structural Health Monitoring: Upcoming Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2009; pp. 373–378.

- Güemes, A.; Fernández-López, A.; Díaz-Maroto, P.F.; Lozano, A.; Sierra-Perez, J. Structural Health Monitoring in Composite Structures by Fiber-Optic Sensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 1094.

- Du, C.; Dutta, S.; Kurup, P.; Yu, T.; Wang, X. A review of railway infrastructure monitoring using fiber optic sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 303, 111728.

- Bao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hoehler, M.S.; Chen, G. Review of Fiber Optic Sensors for Structural Fire Engineering. Sensors 2019, 19, 877.

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, Z.W.; Xiao, W.; Deng, Q.X. Review of fiber optic sensors in geotechnical health monitoring. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2020, 54, 102127.

- Cranch, G.A.; Kirkendall, C.K.; Daley, K.; Motley, S.; Bautista, A.; Salzano, J.; Nash, P.J.; Latchem, J.; Crickmore, R. Large-scale remotely pumped and interrogated fiber-optic interferometric sensor array. Photonics Technol. Lett. IEEE 2003, 15, 1579–1581.

- Majumder, M.; Gangopadhyay, T.K.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Dasgupta, K.; Bhattacharya, D. Fibre Bragg gratings in structural health monitoring—Present status and applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2008, 147, 150–164.

- Li, H.N.; Li, D.S.; Song, G.B. Recent applications of fiber optic sensors to health monitoring in civil engineering. Eng. Struct. 2004, 26, 1647–1657.

- Peng, J.; Jia, S.; Bian, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X. Recent Progress on Electromagnetic Field Measurement Based on Optical Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 2860.

- Tosi, D. Review of Chirped Fiber Bragg Grating (CFBG) Fiber-Optic Sensors and Their Applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 2147.

- Su, Y.D.; Preger, Y.; Burroughs, H.; Sun, C.; Ohodnicki, P.R. Fiber Optic Sensing Technologies for Battery Management Systems and Energy Storage Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 1397.

- Di Sante, R. Fibre optic sensors for structural health monitoring of aircraft composite structures: Recent advances and applications. Sensors 2015, 15, 18666–18713.

- Zakirov, R.; Giyasova, F. Application of Fiber-Optic Sensors for the Aircraft Structure Monitoring. In Safety in Aviation and Space Technologies; Bieliatynskyi, A., Breskich, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 23–32.

- Ecke, W.; Latka, I.; Willsch, R.; Reutlinger, A.; Graue, R. Fibre optic sensor network for spacecraft health monitoring. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 974.

- Nedoma, J.; Kepak, S.; Fajkus, M.; Cubik, J.; Siska, P.; Martinek, R.; Krupa, P. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Compatible Non-Invasive Fibre-Optic Sensors Based on the Bragg Gratings and Interferometers in the Application of Monitoring Heart and Respiration Rate of the Human Body: A Comparative Study. Sensors 2018, 18, 3713.

- Tosi, D.; Schena, E.; Molardi, C.; Korganbayev, S. Fiber optic sensors for sub-centimeter spatially resolved measurements: Review and biomedical applications. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2018, 43, 6–19.

- Yick, J.; Mukherjee, B.; Ghosal, D. Wireless sensor network survey. Comput. Netw. 2008, 52, 2292–2330.

- Othman, M.F.; Shazali, K. Wireless Sensor Network Applications: A Study in Environment Monitoring System. Procedia Eng. 2012, 41, 1204–1210.

- Puccinelli, D.; Haenggi, M. Wireless sensor networks: Applications and challenges of ubiquitous sensing. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 2005, 5, 19–31.

- Borges, L.M.; Velez, F.J.; Lebres, A.S. Survey on the Characterization and Classification of Wireless Sensor Network Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 1860–1890.

- Zhou, B.; Yang, S.; Nguyen, T.H.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V. Wireless Sensor Network Platform for Intrinsic Optical Fiber pH Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 14, 1313–1320.

- Liu, S.P.; Shi, B.; Gu, K.; Zhang, C.C.; He, J.H.; Wu, J.H.; Wei, G.Q. Fiber-optic wireless sensor network using ultra-weak fiber Bragg gratings for vertical subsurface deformation monitoring. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 2557–2573.

- Zrelli, A.; Ezzedine, T. Design of optical and wireless sensors for underground mining monitoring system. Optik 2018, 170, 376–383.

- Bang, H.j.; Jang, M.; Shin, H. Structural health monitoring of wind turbines using fiber Bragg grating based sensing system. In Proceedings of the Sensors and Smart Structures Technologies for Civil, Mechanical, and Aerospace Systems 2011, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–10 March 2011; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011; Volume 7981, pp. 716–723.

- Cooperman, A.; Martinez, M. Load monitoring for active control of wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 189–201.

- Krebber, K.; Habel, W.; Gutmann, T.; Schram, C. Fiber Bragg grating sensors for monitoring of wind turbine blades. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Optical Fibre Sensors, Bruges, Belgium, 23–27 May 2005; Voet, M., Willsch, R., Ecke, W., Jones, J., Culshaw, B., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics. SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; Volume 5855, pp. 1036–1039.

- Konstantaki, M.; Padhye, A.; Anthoulakis, E.; Poumpouridis, N.; Diamantakis, Z.; Gavalas, N.; Laderos, V.; Christodoulou, S.; Pissadakis, S. Optical fiber sensors in agricultural applications. In Proceedings of the Optical Sensing and Detection VII, Strasbourg, France, 3 April–23 May 2022; Berghmans, F., Zergioti, I., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; Volume 12139.

- Zhou, B.; Yang, S.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T. A novel wireless mobile platform to locate and gather data from optical fiber sensors integrated into a WSN. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 3615–3621.

- Lu, L.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z. A portable optical fiber SPR temperature sensor based on a smart-phone. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 25420–25427.

- Markvart, A.A.; Liokumovich, L.B.; Medvedev, I.O.; Ushakov, N.A. Smartphone-Based Interrogation of a Chirped FBG Strain Sensor Inscribed in a Multimode Fiber. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 282–289.