Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The dynamic O-GlcNAc modification of intracellular proteins is an important nutrient sensor for integrating metabolic signals into vast networks of highly coordinated cellular activities. Dysregulation of the sole enzymes responsible for O-GlcNAc cycling, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), and the associated cellular O-GlcNAc profile is a common feature across nearly every cancer type.

- O-GlcNAcylation

- O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT)

- O-GlcNAcase (OGA)

- cancer

- protein–protein interaction (PPI)

1. Introduction

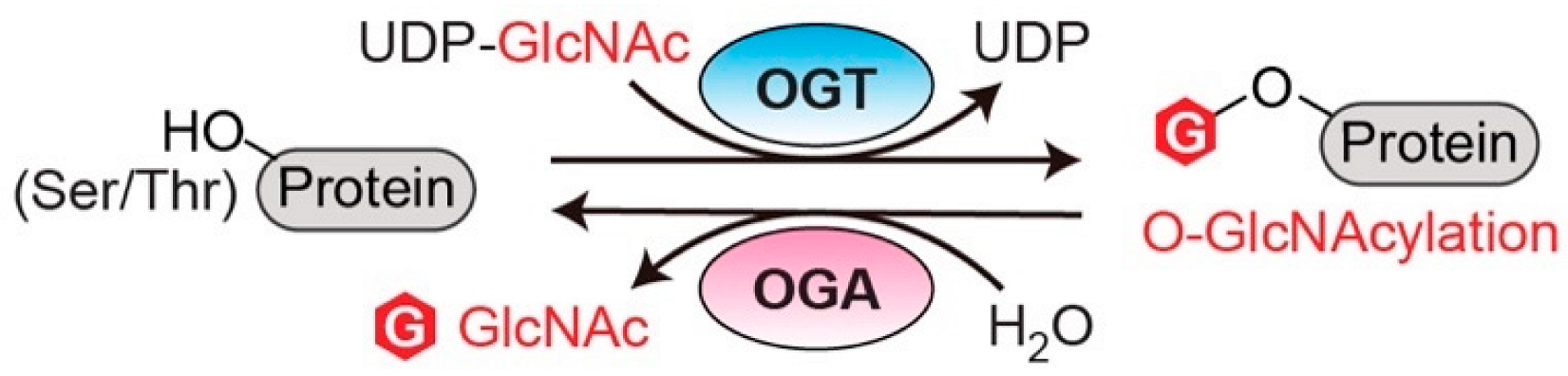

O-linked N-acetylglucosaminylation (O-GlcNAcylation) is an essential post-translational modification (PTM) that dynamically regulates numerous protein functions in response to nutrients and stress [1]. Interestingly, only a single pair of human enzymes maintains the homeostasis of this modification: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) [2][3][4][5][6]. OGT transfers the GlcNAc moiety from the sugar donor UDP-GlcNAc to the serine or threonine residues of protein substrates (Figure 1). On the contrary, OGA removes the sugar moiety from O-GlcNAcylated substrates (Figure 1). This reversible O-GlcNAc cycle dynamically modulates protein stability, enzymatic activity, protein–protein interactions (PPIs), and the crosstalk with other types of PTMs [7][8]. To date, thousands of O-GlcNAcylated proteins have been identified and they play important roles in remarkably diverse cellular processes, including transcription, translation, apoptosis, cell cycle, protein transportation, mitochondrial function, and signal transduction [7][9][10]. Notably, dysregulation of OGT, OGA, and the associated cellular O-GlcNAc profile is commonly detected in all cancers [11]. For instance, upregulated OGT and O-GlcNAcylation are intimately associated with nearly every cancer-related phenotype, ranging from cell proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transformation (EMT), angiogenesis, to metastasis [11][12][13][14]. Emerging evidence also shows that OGT is involved in regulating/activating cancer stem cell potential and resistance in anti-cancer treatments [14][15][16]. On the other side, both up- and down-regulation of OGA protein levels have been observed in different types and grades of cancer [17][18][19][20]. Elevated activity of OGA was also detected in cancer [21]. Furthermore, anti-cancer drugs combined with OGA inhibition using small molecule or genetic approaches have shown synergic inhibitory effects on tumor progression [22][23][24]. More interestingly, a significant correlation between the expression levels of OGT/OGA and the grade/stage of tumors or prognosis has been discovered, promoting mechanistic investigations of these enzymes in cancer [17][25][26]. In general, the abnormal functions of OGT/OGA can make profound impacts on many biological processes, such as metabolic reprogramming, transcription/epigenetic regulation, inflammation, and stress response [27][28][29][30][31]. These dysregulations, often amplified through a large repertoire of O-GlcNAcylated proteins, fuel cancer malignancies and accelerate disease deterioration. These findings raised significant interest in targeting O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes (OGT and OGA) as a potential new anti-cancer strategy. In the past decade, genetic perturbation and the active-site inhibitors of these two enzymes have been widely used to gain fundamental understanding of their roles in normal and disease conditions, and to evaluate their potential for therapeutic development. Exciting progress has been made; however, significant challenges have also become apparent. One of the main challenges is that OGT and OGA are essential enzymes; prolonged knockdown or knockout of either of them leads to embryonic lethality or deterioration of organ functions [32][33]. Inhibition of OGT/OGA’s catalytic site brings similar concerns about unpredictable side effects due to the perturbation of global O-GlcNAcylation [34][35][36][37]. In addition, the non-catalytic functions of OGT and OGA have been recently reported to regulate cell proliferation and tumor cell growth, respectively, indicating that their active-site inhibition may not be sufficient to halt cancers derived from the aberrant non-catalytic functions of O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes [18][38]. Hence, there is a critical need to explore new strategies to target OGT/OGA. To develop such new strategies, a better understanding of how OGT and OGA interact with other proteins (e.g., substrates or non-substrate partners) through regions outside of their immediate catalytic sites would be essential. This knowledge will not only aid in defining the malfunctions of OGT/OGA in complex diseases such as cancer, but also facilitate the development of novel strategies to manipulate the interactions of these enzymes and a subset of proteins without global O-GlcNAc perturbation-induced side effects.

Figure 1. O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes (OGT and OGA) catalyze the reversible protein O-GlcNAcylation. OGT: O-GlcNAc transferase. OGA: O-GlcNAcase. UDP-GlcNAc: uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine.

Perturbed PPIs in cancer (cancer-specific PPIs) is one of the key factors in cancer development [39]. Mapping PPIs has provided invaluable insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms in multiple types of cancer [40]. Moreover, aberrant PPIs are arising as new targets for the development of novel cancer therapy. As many PPI inhibitors have entered clinical trials or applications, this has become an important strategy to impede malignant cancer programming with minimal toxicity [41]. Given the manifold functions of O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes, deciphering their roles from a PPI perspective promises fruitful discoveries and may open new doors for cancer therapeutic interventions. Compared to many other cancer-related proteins (e.g., BCL2, p53, etc.), the protein interactions of OGT/OGA have been significantly less explored, potentially restricted by their transient protein interactions with many O-GlcNAcylated substrates and a lack of a conserved recognition motif [42].

2. Structural Insights of O-GlcNAc Cycling Enzymes as Potential Multi-Interface Hubs for Regulating Complex PPI Networks

Analyses using interdisciplinary approaches, including structure, bioinformatics, and multi-omics, have greatly accelerated our understanding of cancer-specific PPI interface properties and topological features. For example, intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which play a pivotal role in modulating the plasticity of PPI networks, were found to be significantly enriched in cancer-specific PPIs in the human proteome [43]. Interestingly, a recent study found that protein hubs in cancer-specific PPIs tend to possess more distinct binding sites for various protein partners than non-cancer related proteins [44]. These findings indicate that cancer-specific hubs may have acquired unique structural features to coordinate diverse modules for maintaining the high plasticity and complexity of cancer networks. Of particular interest here, OGT and OGA are potential multi-interface hubs in PPIs, in agreement with their capability to accommodate remarkably diverse protein substrates and the fact that O-GlcNAcylation is often detected in the disordered regions of proteins [45]. While still far from a complete understanding of the protein recognition mechanisms of OGT/OGA, the structural features discussed below start to reveal the molecular basis underlying the selectivity and plasticity of their protein interactions, supporting that the O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes are essential regulators of the dynamic, scale-free PPI networks in cancer.

3. Systematic Analyses of OGT/OGA Associated PPI Networks in Cancer

O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes (OGT and OGA) operate their functions by interactions with other biomolecules. The multiprotein complexes of OGT/OGA are of fundamental importance to decipher their roles in various biological processes. As previously reported that aberrant PPIs underlie the etiology of cancer, decoding the molecular connections of dysregulated OGT/OGA–protein networks in cancer will be important for therapeutic innovations [46]. To date, rapidly accumulating knowledge of O-GlcNAcylated proteins, and a few high-throughput studies of OGT interactions including the analyses using protein microarray in vitro [47] and the quantitative proteomics in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells [48], have enabled the establishment of a massive compendium about the OGT interacting proteins (OGT-PIN) [49]. Less information about OGA binding partners has been disclosed; however, a potential high-level of overlap may exist between OGT– and OGA–substrate interactions. Despite these propitious findings, only a few systematic analyses of OGT/OGA-associated PPI networks have been reported in cancer models.

The profiling of OGT/OGA-associated PPIs in cancer cells typically apply affinity purification or proximity biotinylation coupled with quantitative LC-MS/MS analysis (AP-MS or BioID-MS) [50][51]. For instance, the functions of mOGT in breast cancer cells have been investigated through its interactomes [52]. Compared to ncOGT, the relatively short TPR region (9 instead of 13.5 TPRs) and the unique mitochondrial localization imply that mOGT may form a PPI network different from ncOGT. This is in agreement with the distinct substrate profiles and cytotoxic effects of mOGT observed in mammalian cells [53][54]. Following endogenous ncOGT knockdown and HaloTag-mOGT affinity purification from mitochondrial fractions, more than 40 mitochondrial proteins have been identified as mOGT binding partners in at least two different breast cancer cell lines compared to HaloTag control [52]. These proteins participate in almost every aspect of mitochondrial functions, including mitochondrial transport, respiration, translation, fatty acid metabolism, apoptosis, and mtDNA processes. This finding is also in line with the observation in cervical cancer HeLa cells that mOGT contributes to mitochondrial structure and function, as well as cancer cell survival [55]. Surprisingly, a few nuclear proteins were also detected as mOGT binders. This implicates potentially distinct roles of different OGT isoforms in cancer cells. While these discoveries on mOGT–protein interactions are informative, further analyses will be needed to define cancer-specific PPIs of mOGT.

Protein interactions with O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes consist of transient or weak interactions. The recently developed proximity biotinylation (BioID) technique is well-suited for this type of detection [51]. It was applied to investigate OGA-mediated oxidative stress response in osteosarcoma U2OS cells [56]. In this study, ectopic expression of OGA fused with biotin ligase mBirA can biotinylate proteins bound or in proximity to OGA. The changes of OGA–protein interactions in response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress were identified by LC-MS/MS detection of biotinylated proteins. As a result, dozens of OGA binding partners have been identified as significantly regulated, including fatty acid synthase (FAS), filamin-A (FLNA), heat shock cognate 70-kDa protein (HSC70), and OGT. Interestingly, biochemical analyses further revealed that the interaction with FAS suppressed OGA’s catalytic activity and modulated the stress adaptation of cancer cells. Using the AP-MS approach, another study identified OGA–protein interactions in HeLa cells [18], showing significant enrichment of cellular functions, such as RNA splicing, mRNA processing, cytoskeleton organization, intracellular transport, and mitosis (GO term analysis of the data from Table S1 in [18] using DAVID [57][58]). Intriguingly, many of these OGA PPI functions were absent in the OGA pHAT domain mutant (Y891F), except for RNA splicing and mRNA processing (GO term analysis of the data from Table S2 in [18] using DAVID), suggesting that the pHAT domain is indispensable for maintaining the integrity of OGA PPI networks. Notably, the same study also found that OGA was upregulated in many types of cancer and drove aerobic glycolysis and tumor growth by inhibiting pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2). Further experiments suggested that the activity of PKM2 was dysregulated by OGA complex-associated acetylation and O-GlcNAcylation under cancer-related high glucose conditions. Overall, these studies have begun to uncover the abnormal PPIs of OGT/OGA in cancer models. With advances in proteomics and bioinformatics, the researchers envision that the systematic analyses of protein interactions with OGT/OGA (not restricted to O-GlcNAcylated proteins) will identify new, cancer-specific PPIs and help define the oncogenic properties of these O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes in cancer biology.

4. Dysregulated Protein Functions by Rewired OGT/OGA Protein Networks in Cancer

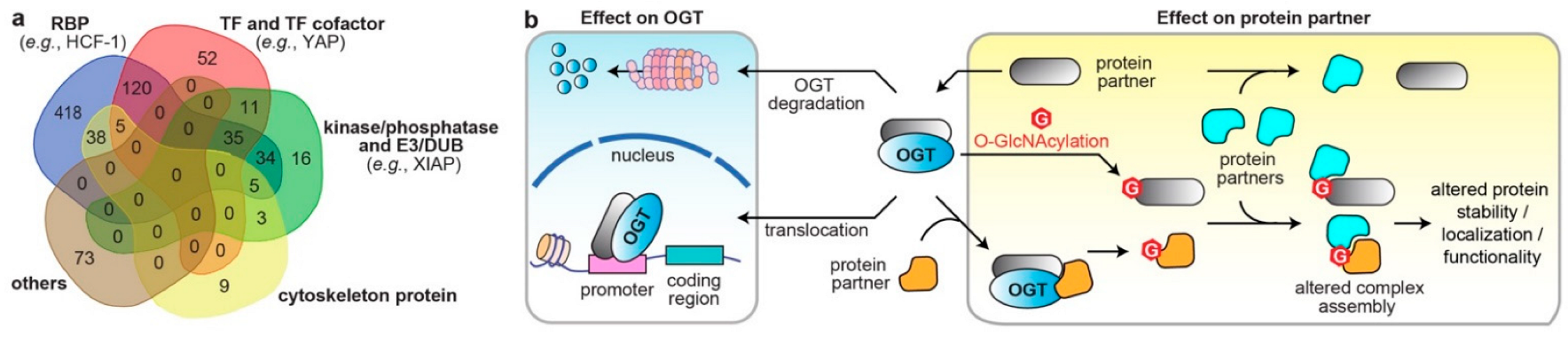

PPIs are the frameworks for signal transmission in conducting cellular events. The broad-spectrum effect of O-GlcNAcylation suggest that OGT/OGA PPIs regulate the spatiotemporal communication of many biological processes. Analysis of all reported interacting partners of human OGT/OGA in the curated databases, OGT-PIN (high-stringency partners) [49] and PINA [59], demonstrated diverse molecular characters, including nucleotide binder, kinase/phosphatase, E3 ubiquitin ligase/deubiquitinase (DUB), and cytoskeleton (Figure 2a). Herein, abnormal OGT/OGA networks can affect proteins at multiple levels, including PTM, conformation, and association with other biomolecules, which consequently modulate the enzyme activity, protein stability and transportation, among others [7][9]. Below, the researchers highlight a few representative examples, in which the OGT/OGA–protein interactions have been validated by orthogonal methods, such as immunoprecipitation, to demonstrate the diverse molecular impacts of these PPIs on the malignant programming of cancer cells (Figure 2b). These studies illustrate that O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes can form divergent protein complexes with substrates and/or non-substrate partners and execute multifunctional roles in cancer. While most studies were focused on OGT, it is likely that OGA could apply similar mechanisms.

Figure 2. The diverse molecular impacts of protein interactions with O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes. (a) Classification of reported OGT/OGA binding partners in cancer. The information of OGT and OGA binding partners was from database OGT-PIN (high-stringency interaction proteins) and PINA, respectively. The binding partners were categorized using the databases AnimalTFDB 3.0 [60], KinMap [61], DEPOD [62], UbiBrowser 2.0 [63], UbiNet 2.0 [64], RBP2GO [65], and gene ontology (GO term: cytoskeleton) from DAVID [58]. The venn diagram was generated from http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/ (accessed on 15 October 2022). RBP, RNA binding protein; TF, transcription factor; E3, E3 ubiquitin ligase; DUB, deubiquitinase. (b) Different molecular mechanisms underlying the protein interactions with O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes in dysregulating protein functions in cancer cells (OGT is shown as an example).

4.1. Altered Cellular Localization and Protein Stability of O-GlcNAc Cycling Enzymes

The chromatin association of OGT and OGA has been detected in different types of cells, which is consistent with their essential roles in transcription and epigenetic regulation [66][67]. Some binding partners/substrates of OGT have been found to assist the recruitment of OGT to promoter regions [67][68][69][70][71][72]. One of the most studied partners is mSin3A, an isoform of mammalian Sin3 that serves as a scaffold for histone deacetylase complexes in gene regulation [73]. In hepatoma HepG2 cells, mSin3A interacts with the OGT N-terminal TPR region and recruits it to the promoters for transcriptional repression [71]. This example demonstrates that PPIs modulate OGT translocalization and its associated epigenetic functions. On the other hand, aberrant protein interactions in cancer cells can alter the stability of O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes, which may further dysregulate their PPI networks and affect cancer cell growth. In a surprising discovery, histone demethylase LSD2 was found to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, to directly interact with OGT, and to induce its ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation [74]. While the O-GlcNAcylation status of LSD2 remains unknown, the interaction of LSD2 and OGT displayed an anti-growth effect in lung cancer A549 cells by reducing the stability and protein level of OGT. Another OGT interactor with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity is the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) [75]. In colon cancer HCT116 cells, XIAP directly interacts with OGT and induces its proteasomal degradation. More interestingly, XIAP can be O-GlcNAcylated, and the modification is essential for the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of XIAP toward OGT specifically, but not other protein substrates in HCT116 cells. Thus, O-GlcNAcylated XIAP suppresses cancer cell growth and invasion by degrading OGT. However, significantly reduced OGT would downregulate O-GlcNAcylation of XIAP. This reciprocal modulation is an elegant example showing how cancer cells control the stability/level of O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes through specific protein interactions.

4.2. Effects on the Direct Binding Partners/Substrates of O-GlcNAc Cycling Enzymes

Aberrant interactions with O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes can modulate the O-GlcNAcylation of binding partners, leading to altered protein stability, localization, and functionality [7][12]. This is a prevailing mechanism of the abnormal OGT/OGA networks underlying cancer development, also in line with the fact that O-GlcNAcylation is essential for transcription and translation, which are often reprogramed in cancer [76][77]. As previously reported, O-GlcNAcylation of many transcription factors, such as Sp1 [78], FOXO1 [79], p53 [80], and NF-κB [81], can upregulate their activities in cancer cells by increasing their protein stability and nuclear translocation. The molecular mechanisms usually involve aberrant OGT–protein-association and the resulted O-GlcNAcylation that may alter the assembly of multiprotein complexes (Figure 2b). A typical example is the notorious cancer promoter, SIRT7, which is a member of the NAD+-dependent deacetylase Sirtuin family [82]. OGT was detected in complex with SIRT7 in different pancreatic cancer cell lines [83]. The interaction occurred through the C-terminus of SIRT7 and the TPR region of OGT, inducing O-GlcNAcylation and facilitating the stabilization of SIRT7 by interfering its interaction with REGγ proteasome. Elevated SIRT7 deacetylated the lysine 18 of histone H3 (H3K18), promoted the enrichment of SIRT7 at the promoters, and inhibited the expression of tumor suppressors to fuel cancer progression. In another example, the ribosomal receptor for activated C-kinase 1 (RACK1), an important component of the 40S ribosome subunit, was identified to interact with OGT in hepatoma cells [84]. O-GlcNAcylated RACK1 showed significantly higher stability and ribosome localization, and more importantly, promoted its association with another kinase PKCβII, which is an essential signaling molecule for RACK1 initiated translation. The RACK1/PKCβII complex stimulated the translation and expression of several oncogenes, driving hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Rewired protein networks of OGT have also been reported for the oncogene YAP, which is a transcription factor in Hippo signaling [85]. Abnormally activated Hippo pathway and YAP-stimulated gene expression give rise to uncontrolled cell growth and tumor formation [86]. In contrast, YAP phosphorylation by kinase LATS1 increases its cytoplasmic translocalization and degradation, leading to negative regulation of Hippo signaling [86][87]. Interestingly, YAP was found to interact with OGT in vitro and in cells, and the O-GlcNAcylation on the S109 residue suppressed the association of YAP with LATS1, and the phosphorylation of YAP at S237. Hence, in pancreatic cells, the aberrant OGT interaction and O-GlcNAcylation of YAP promote its dephosphorylation, nuclear localization, and transcriptional activity, fueling Hippo signaling and tumor growth [85]. Cancer cells also apply similar means to antagonize the genotoxicity from commonly used chemotherapeutic agents, such as adriamycin (adm) [88]. A study in breast cancer cells detected that MTA1, a highly deregulated oncogene involved in the stress adaptation of cancer, is an OGT substrate [89][90]. Intriguingly, MTA1 displayed enhanced interaction with OGT in adm-resistant (MCF7/ADR) cells compared to adm-sensitive (MCF7) cells [90]. Immunoprecipitation and genome-wide analysis further showed that O-GlcNAcylation of MTA1 promoted its association with components of nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation (NuRD) complex, including HDAC1, MBD3, and CHD4, and recruited MTA1 to the promoter of stress-adaptive genes for transcriptional activation. Therefore, MTA1–OGT interaction and its aberrant O-GlcNAcylation protected the breast cancer cells against genotoxic stress, leading to drug resistance. It would be interesting to evaluate whether OGA–protein interactions also engage in modulating similar protein complexes in cancer. In summary, aberrant OGT–protein interactions and O-GlcNAcylation deregulate the assembly of the protein with other biomolecules, leading to diminished proteolysis and upregulated functions that may promote cancer cell growth. However, exceptions do exist in other cellular conditions [91]. Please refer to [11][13][31] for more detailed reviews about the regulation of O-GlcNAcylation on protein substrates in cancer.

4.3. Modulations through Binding Adaptors

One of the hypotheses regarding how OGT/OGA recognizes their protein substrates is through protein adaptors [92]. Recently, a few OGT adaptors have been identified in different types of cancer cells. In hepatoma FAO cells, it was reported that the interaction of OGT with HCF-1, a transcriptional cofactor playing critical roles in cell cycle and stem cell regulation, enhanced the O-GlcNAcylation of transcription factor PGC-1α [93]. Further analysis demonstrated that O-GlcNAcylated PGC-1α displayed increased stability by forming a stronger complex with deubiquitinase BAP1, and thereby promoted the gluconeogenic gene expression in response to glucose availability. Another study discovered that an anti-viral and pro-inflammatory protein, IFIT3, assisted OGT interaction with substrate VDAC2 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and patient-derived primary cells [94]. VDAC2 is a channel protein involved in mitochondria-associated apoptosis [95]. Upregulated O-GlcNAcylation of VDAC2 protected highly metastatic cancer cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, leading to drug resistance [94]. CEMIP, a cell-migration inducing protein promoting metastasis through glutamine metabolic reprogramming, is another OGT adaptor identified in colorectal cancer and was recently discovered as a metastasis-related protein [96]. It stabilized the interaction of OGT with substrate β-catenin, resulting in elevated O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin and displacing it from its complex with cadherins in the cytomembrane for nuclear translocation and transcription regulation. CEMIP- and OGT-induced nuclear accumulation of β-catenin can transactivate genes in metabolic reprogramming and promote tumor growth. While the O-GlcNAcylation status of CEMIP was not reported in this case, its middle and C-terminal regions were responsible for OGT and β-catenin binding, respectively. Intriguingly, cells with CEMIP knockdown or overexpression altered the O-GlcNAcylation of many proteins, suggesting that this adaptor mediates the interactions of O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes with many other substrates. Overall, these interesting discoveries strongly support that the binding adaptors can modulate the PPI networks of O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes in malignant transformation. Future investigations are expected to uncover additional novel adaptors and their mechanisms of action in cancer.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14205135

References

- Hart, G.W. Nutrient Regulation of Signaling and Transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2211–2231.

- Haltiwanger, R.S.; Blomberg, M.A.; Hart, G.W. Glycosylation of Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Proteins. Purification and Characterization of a Uridine Diphospho-N-Acetylglucosamine:Polypeptide Beta-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 9005–9013.

- Lubas, W.A.; Frank, D.W.; Krause, M.; Hanover, J.A. O-Linked GlcNAc Transferase Is a Conserved Nucleocytoplasmic Protein Containing Tetratricopeptide Repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 9316–9324.

- Heckel, D.; Comtesse, N.; Brass, N.; Blin, N.; Zang, K.D.; Meese, E. Novel Immunogenic Antigen Homologous to Hyaluronidase in Meningioma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998, 7, 1859–1872.

- Comtesse, N.; Maldener, E.; Meese, E. Identification of a Nuclear Variant of MGEA5, a Cytoplasmic Hyaluronidase and a β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 283, 634–640.

- Gao, Y.; Wells, L.; Comer, F.I.; Parker, G.J.; Hart, G.W. Dynamic O-Glycosylation of Nuclear and Cytosolic Proteins:Cloning and Characterization of A Neutral, Cytosolic Beta-N-Acetylglucosaminidase From Human Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 9838–9845.

- Yang, X.; Qian, K. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: Emerging Mechanisms and Functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 452–465.

- Laarse, S.A.M.; Leney, A.C.; Heck, A.J.R. Crosstalk between Phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation: Friend or Foe. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3152–3167.

- Bond, M.R.; Hanover, J.A. A Little Sugar Goes a Long Way: The Cell Biology of O-GlcNAc. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 869–880.

- Xue, Q.; Yan, R.; Ji, S.; Yu, S. Regulation of Mitochondrial Network Homeostasis by O-GlcNAcylation. Mitochondrion 2022, 65, 45–55.

- de Queiroz, R.M.; Carvalho, Ã.; Dias, W.B. O-GlcNAcylation: The Sweet Side of the Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 132.

- Lee, J.B.; Pyo, K.-H.; Kim, H.R. Role and Function of O-GlcNAcylation in Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5365.

- Fardini, Y.; Dehennaut, V.; Lefebvre, T.; Issad, T. O-GlcNAcylation: A New Cancer Hallmark? Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 99.

- Ma, Z.; Vosseller, K. O-GlcNAc in Cancer Biology. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 719–733.

- Itkonen, H.M.; Loda, M.; Mills, I.G. O-GlcNAc Transferase—An Auxiliary Factor or a Full-Blown Oncogene? Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 555–564.

- Very, N.; El Yazidi-Belkoura, I. Targeting O-GlcNAcylation to Overcome Resistance to Anti-Cancer Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 960312.

- Lu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liang, T.; Bai, X. O-GlcNAcylation: An Important Post-Translational Modification and a Potential Therapeutic Target for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 115.

- Singh, J.P.; Qian, K.; Lee, J.-S.; Zhou, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, B.; Ong, Q.; Ni, W.; Jiang, M.; Ruan, H.-B.; et al. O-GlcNAcase Targets Pyruvate Kinase M2 to Regulate Tumor Growth. Oncogene 2020, 39, 560–573.

- Krześlak, A.; Forma, E.; Bernaciak, M.; Romanowicz, H.; Bryś, M. Gene Expression of O-GlcNAc Cycling Enzymes in Human Breast Cancers. Clin. Exp. Med. 2012, 12, 61–65.

- Qian, K.; Wang, S.; Fu, M.; Zhou, J.; Singh, J.P.; Li, M.-D.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J.; Nie, Y.; et al. Transcriptional Regulation of O-GlcNAc Homeostasis Is Disrupted in Pancreatic Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 13989–14000.

- Krzeslak, A.; Pomorski, L.; Lipinska, A. Elevation of Nucleocytoplasmic β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase (O-GlcNAcase) Activity in Thyroid Cancers. Int. Mol. Med. 2010, 25, 643–648.

- Ding, N.; Ping, L.; Shi, Y.; Feng, L.; Zheng, X.; Song, Y.; Zhu, J. Thiamet-G-Mediated Inhibition of O-GlcNAcase Sensitizes Human Leukemia Cells to Microtubule-Stabilizing Agent Paclitaxel. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 392–397.

- Luanpitpong, S.; Chanthra, N.; Janan, M.; Poohadsuan, J.; Samart, P.; U-Pratya, Y.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Issaragrisil, S. Inhibition of O -GlcNAcase Sensitizes Apoptosis and Reverses Bortezomib Resistance in Mantle Cell Lymphoma through Modification of Truncated Bid. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 484–496.

- Very, N.; Hardivillé, S.; Decourcelle, A.; Thévenet, J.; Djouina, M.; Page, A.; Vergoten, G.; Schulz, C.; Kerr-Conte, J.; Lefebvre, T.; et al. Thymidylate Synthase O-GlcNAcylation: A Molecular Mechanism of 5-FU Sensitization in Colorectal Cancer. Oncogene 2022, 41, 745–756.

- Starska, K.; Forma, E.; Brzezińska-Błaszczyk, E.; Lewy-Trenda, I.; Bryś, M.; Jóźwiak, P.; Krześlak, A. Gene and Protein Expression of O-GlcNAc-Cycling Enzymes in Human Laryngeal Cancer. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 15, 455–468.

- Yang, Y.R.; Jang, H.-J.; Yoon, S.; Lee, Y.H.; Nam, D.; Kim, I.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.H.; Kang, B.H.; et al. OGA Heterozygosity Suppresses Intestinal Tumorigenesis in Apcmin/+ Mice. Oncogenesis 2014, 3, e109.

- Jóźwiak, P.; Forma, E.; Bryś, M.; Anna Krześlak, A. O-GlcNAcylation and Metabolic Reprograming in Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 145.

- Olivier-Van Stichelen, S.; Hanover, J.A. You Are What You Eat: O-Linked N-Acetylglucosamine in Disease, Development and Epigenetics. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 339–345.

- Parker, M.P.; Peterson, K.R.; Slawson, C. O-GlcNAcylation and O-GlcNAc Cycling Regulate Gene Transcription: Emerging Roles in Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 1666.

- Ouyang, M.; Yu, C.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Duan, F. O-GlcNAcylation and Its Role in Cancer-Associated Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 861559.

- Slawson, C.; Hart, G.W. O-GlcNAc Signalling: Implications for Cancer Cell Biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 678–684.

- Yang, Y.R.; Song, M.; Lee, H.; Jeon, Y.; Choi, E.-J.; Jang, H.-J.; Moon, H.Y.; Byun, H.-Y.; Kim, E.-K.; Kim, D.H.; et al. O-GlcNAcase Is Essential for Embryonic Development and Maintenance of Genomic Stability: Genomic Instability by Dysregulation O-GlcNAcylation. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 439–448.

- Olivier-Van Stichelen, S.; Abramowitz, L.K.; Hanover, J.A. X Marks the Spot: Does It Matter That O-GlcNAc Transferase Is an X-Linked Gene? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 201–207.

- Barkovskaya, A.; Seip, K.; Hilmarsdottir, B.; Maelandsmo, G.M.; Moestue, S.A.; Itkonen, H.M. O-GlcNAc Transferase Inhibition Differentially Affects Breast Cancer Subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5670.

- Trapannone, R.; Rafie, K.; van Aalten, D.M.F. O-GlcNAc Transferase Inhibitors: Current Tools and Future Challenges. Biohem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 88–93.

- Muha, V.; Authier, F.; Szoke-Kovacs, Z.; Johnson, S.; Gallagher, J.; McNeilly, A.; McCrimmon, R.J.; Teboul, L.; van Aalten, D.M.F. Loss of O-GlcNAcase Catalytic Activity Leads to Defects in Mouse Embryogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100439.

- Huynh, V.N.; Wang, S.; Ouyang, X.; Wani, W.Y.; Johnson, M.S.; Chacko, B.K.; Jegga, A.G.; Qian, W.-J.; Chatham, J.C.; Darley-Usmar, V.M.; et al. Defining the Dynamic Regulation of O-GlcNAc Proteome in the Mouse Cortex—The O-GlcNAcylation of Synaptic and Trafficking Proteins Related to Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging 2021, 2, 757801.

- Levine, Z.G.; Potter, S.C.; Joiner, C.M.; Fei, G.Q.; Nabet, B.; Sonnett, M.; Zachara, N.E.; Gray, N.S.; Paulo, J.A.; Walker, S. Mammalian Cell Proliferation Requires Noncatalytic Functions of O-GlcNAc Transferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016778118.

- Gulati, S.; Cheng, T.M.K.; Bates, P.A. Cancer Networks and beyond: Interpreting Mutations Using the Human Interactome and Protein Structure. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013, 23, 219–226.

- Yoon, T.-Y.; Lee, H.-W. Shedding Light on Complexity of Protein–Protein Interactions in Cancer. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 53, 75–81.

- Lu, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, J.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, C.; Tong, R.; Shi, J. Recent Advances in the Development of Protein–Protein Interactions Modulators: Mechanisms and Clinical Trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 213.

- Hu, C.; Worth, M.; Li, H.; Jiang, J. Chemical and Biochemical Strategies To Explore the Substrate Recognition of O-GlcNAc-Cycling Enzymes. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 312–318.

- Uversky, V.N.; Davé, V.; Iakoucheva, L.M.; Malaney, P.; Metallo, S.J.; Pathak, R.R.; Joerger, A.C. Pathological Unfoldomics of Uncontrolled Chaos: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Human Diseases. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6844–6879.

- Kar, G.; Gursoy, A.; Keskin, O. Human Cancer Protein-Protein Interaction Network: A Structural Perspective. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000601.

- Nishikawa, I.; Nakajima, Y.; Ito, M.; Fukuchi, S.; Homma, K.; Nishikawa, K. Computational Prediction of O-Linked Glycosylation Sites That Preferentially Map on Intrinsically Disordered Regions of Extracellular Proteins. IJMS 2010, 11, 4991–5008.

- Grechkin, M.; Logsdon, B.A.; Gentles, A.J.; Lee, S.-I. Identifying Network Perturbation in Cancer. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1004888.

- Deng, R.-P.; He, X.; Guo, S.-J.; Liu, W.-F.; Tao, Y.; Tao, S.-C. Global Identification of O-GlcNAc Transferase (OGT) Interactors by a Human Proteome Microarray and the Construction of an OGT Interactome. Proteomics 2014, 14, 1020–1030.

- Martinez, M.; Renuse, S.; Kreimer, S.; O’Meally, R.; Natov, P.; Madugundu, A.K.; Nirujogi, R.S.; Tahir, R.; Cole, R.; Pandey, A.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveals That the OGT Interactome Is Remodeled in Response to Oxidative Stress. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021, 20, 100069.

- Ma, J.; Hou, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Wu, C. OGT Protein Interaction Network (OGT-PIN): A Curated Database of Experimentally Identified Interaction Proteins of OGT. IJMS 2021, 22, 9620.

- Morris, J.H.; Knudsen, G.M.; Verschueren, E.; Johnson, J.R.; Cimermancic, P.; Greninger, A.L.; Pico, A.R. Affinity Purification–Mass Spectrometry and Network Analysis to Understand Protein-Protein Interactions. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2539–2554.

- Sears, R.M.; May, D.G.; Roux, K.J. BioID as a Tool for Protein-Proximity Labeling in Living Cells. In Enzyme-Mediated Ligation Methods; Nuijens, T., Schmidt, M., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2012, pp. 299–313. ISBN 978-1-4939-9545-5.

- Jóźwiak, P.; Ciesielski, P.; Zakrzewski, P.K.; Kozal, K.; Oracz, J.; Budryn, G.; Żyżelewicz, D.; Flament, S.; Vercoutter-Edouart, A.-S.; Bray, F.; et al. Mitochondrial O-GlcNAc Transferase Interacts with and Modifies Many Proteins and Its Up-Regulation Affects Mitochondrial Function and Cellular Energy Homeostasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2956.

- Lazarus, B.D.; Love, D.C.; Hanover, J.A. Recombinant O-GlcNAc Transferase Isoforms: Identification of O-GlcNAcase, Yes Tyrosine Kinase, and Tau as Isoform-Specific Substrates. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 415–421.

- Shin, S.-H.; Love, D.C.; Hanover, J.A. Elevated O-GlcNAc-Dependent Signaling through Inducible MOGT Expression Selectively Triggers Apoptosis. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 885–893.

- Sacoman, J.L.; Dagda, R.Y.; Burnham-Marusich, A.R.; Dagda, R.K.; Berninsone, P.M. Mitochondrial O-GlcNAc Transferase (MOGT) Regulates Mitochondrial Structure, Function, and Survival in HeLa Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 4499–4518.

- Groves, J.A.; Maduka, A.O.; O’Meally, R.N.; Cole, R.N.; Zachara, N.E. Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibits the O-GlcNAcase during Oxidative Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6493–6511.

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and Integrative Analysis of Large Gene Lists Using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57.

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: A Web Server for Functional Enrichment Analysis and Functional Annotation of Gene Lists (2021 Update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W216–W221.

- Du, Y.; Cai, M.; Xing, X.; Ji, J.; Yang, E.; Wu, J. PINA 3.0: Mining Cancer Interactome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1351–D1357.

- Hu, H.; Miao, Y.-R.; Jia, L.-H.; Yu, Q.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, A.-Y. AnimalTFDB 3.0: A Comprehensive Resource for Annotation and Prediction of Animal Transcription Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D33–D38.

- Eid, S.; Turk, S.; Volkamer, A.; Rippmann, F.; Fulle, S. KinMap: A Web-Based Tool for Interactive Navigation through Human Kinome Data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 16.

- Damle, N.P.; Köhn, M. The Human DEPhOsphorylation Database DEPOD: 2019 Update. Database 2019, 2019, baz133.

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; He, M.; Kong, X.; Jiang, P.; Liu, X.; Diao, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Ling, X.; et al. UbiBrowser 2.0: A Comprehensive Resource for Proteome-Wide Known and Predicted Ubiquitin Ligase/Deubiquitinase–Substrate Interactions in Eukaryotic Species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D719–D728.

- Li, Z.; Chen, S.; Jhong, J.-H.; Pang, Y.; Huang, K.-Y.; Li, S.; Lee, T.-Y. UbiNet 2.0: A Verified, Classified, Annotated and Updated Database of E3 Ubiquitin Ligase–Substrate Interactions. Database 2021, 2021, baab010.

- Caudron-Herger, M.; Jansen, R.E.; Wassmer, E.; Diederichs, S. RBP2GO: A Comprehensive Pan-Species Database on RNA-Binding Proteins, Their Interactions and Functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D425–D436.

- Hanover, J.A.; Krause, M.W.; Love, D.C. Linking Metabolism to Epigenetics through O-GlcNAcylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 312–321.

- Voigt, P.; Tee, W.-W.; Reinberg, D. A Double Take on Bivalent Promoters. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1318–1338.

- Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Bian, C.; Fujiki, R.; Yu, X. TET2 Promotes Histone O-GlcNAcylation during Gene Transcription. Nature 2013, 493, 561–564.

- Deplus, R.; Delatte, B.; Schwinn, M.K.; Defrance, M.; Méndez, J.; Murphy, N.; Dawson, M.A.; Volkmar, M.; Putmans, P.; Calonne, E.; et al. TET2 and TET3 Regulate GlcNAcylation and H3K4 Methylation through OGT and SET1/COMPASS. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 645–655.

- Ito, R.; Katsura, S.; Shimada, H.; Tsuchiya, H.; Hada, M.; Okumura, T.; Sugawara, A.; Yokoyama, A. TET3-OGT Interaction Increases the Stability and the Presence of OGT in Chromatin. Genes Cells 2014, 19, 52–65.

- Yang, X.; Zhang, F.; Kudlow, J.E. Recruitment of O-GlcNAc Transferase to Promoters by Corepressor MSin3A. Cell 2002, 110, 69–80.

- Vella, P.; Scelfo, A.; Jammula, S.; Chiacchiera, F.; Williams, K.; Cuomo, A.; Roberto, A.; Christensen, J.; Bonaldi, T.; Helin, K.; et al. Tet Proteins Connect the O-Linked N-Acetylglucosamine Transferase Ogt to Chromatin in Embryonic Stem Cells. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 645–656.

- Dannenberg, J.-H.; David, G.; Zhong, S.; van der Torre, J.; Wong, W.H.; DePinho, R.A. MSin3A Corepressor Regulates Diverse Transcriptional Networks Governing Normal and Neoplastic Growth and Survival. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1581–1595.

- Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Yang, H.; Xu, Y. Histone Demethylase LSD2 Acts as an E3 Ubiquitin Ligase and Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth through Promoting Proteasomal Degradation of OGT. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 47–59.

- Seo, H.G.; Kim, H.B.; Yoon, J.Y.; Kweon, T.H.; Park, Y.S.; Kang, J.; Jung, J.; Son, S.; Yi, E.C.; Lee, T.H.; et al. Mutual Regulation between OGT and XIAP to Control Colon Cancer Cell Growth and Invasion. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 815.

- Bradner, J.E.; Hnisz, D.; Young, R.A. Transcriptional Addiction in Cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 629–643.

- Robichaud, N.; Sonenberg, N.; Ruggero, D.; Schneider, R.J. Translational Control in Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a032896.

- Yang, X.; Su, K.; Roos, M.D.; Chang, Q.; Paterson, A.J.; Kudlow, J.E. O-Linkage of N-Acetylglucosamine to Sp1 Activation Domain Inhibits Its Transcriptional Capability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6611–6616.

- Housley, M.P.; Rodgers, J.T.; Udeshi, N.D.; Kelly, T.J.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Puigserver, P.; Hart, G.W. O-GlcNAc Regulates FoxO Activation in Response to Glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16283–16292.

- Yang, W.H.; Kim, J.E.; Nam, H.W.; Ju, J.W.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Cho, J.W. Modification of P53 with O-Linked N-Acetylglucosamine Regulates P53 Activity and Stability. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1074–1083.

- Ramakrishnan, P.; Clark, P.M.; Mason, D.E.; Peters, E.C.; Hsieh-Wilson, L.C.; Baltimore, D. Activation of the Transcriptional Function of the NF-ΚB Protein c-Rel by O-GlcNAc Glycosylation. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, ra75.

- Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, K.S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, W.-G. Advances in Cellular Characterization of the Sirtuin Isoform, SIRT7. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 652.

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.; Lou, J.; Lin, C.; Gong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y. O-GlcNAcylation and Stablization of SIRT7 Promote Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Blocking the SIRT7-REGγ Interaction. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 1970–1981.

- Duan, F.; Wu, H.; Jia, D.; Wu, W.; Ren, S.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Guo, X.; Liu, F.; Ruan, Y.; et al. O-GlcNAcylation of RACK1 Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1191–1202.

- Peng, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Q.; Shen, P.; Zhen, B.; Qian, X.; et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP Pathway by Glucose Sensor O-GlcNAcylation. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 591–604.e5.

- Calses, P.C.; Crawford, J.J.; Lill, J.R.; Dey, A. Hippo Pathway in Cancer: Aberrant Regulation and Therapeutic Opportunities. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 297–307.

- Hao, Y.; Chun, A.; Cheung, K.; Rashidi, B.; Yang, X. Tumor Suppressor LATS1 Is a Negative Regulator of Oncogene YAP. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 5496–5509.

- Blum, R.H. Adriamycin: A New Anticancer Drug with Significant Clinical Activity. Ann. Intern. Med. 1974, 80, 249.

- Sen, N.; Gui, B.; Kumar, R. Role of MTA1 in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014, 33, 879–889.

- Xie, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. O-GlcNAc Modification Regulates MTA1 Transcriptional Activity during Breast Cancer Cell Genotoxic Adaptation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129930.

- King, D.T.; Serrano-Negrón, J.E.; Zhu, Y.; Moore, C.L.; Shoulders, M.D.; Foster, L.J.; Vocadlo, D.J. Thermal Proteome Profiling Reveals the O-GlcNAc-Dependent Meltome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3833–3842.

- Stephen, H.M.; Adams, T.M.; Wells, L. Regulating the Regulators: Mechanisms of Substrate Selection of the O-GlcNAc Cycling Enzymes OGT and OGA. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 724–733.

- Ruan, H.-B.; Han, X.; Li, M.-D.; Singh, J.P.; Qian, K.; Azarhoush, S.; Zhao, L.; Bennett, A.M.; Samuel, V.T.; Wu, J.; et al. O-GlcNAc Transferase/Host Cell Factor C1 Complex Regulates Gluconeogenesis by Modulating PGC-1α Stability. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 226–237.

- Wang, Z.; Qin, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Popp, M.; Popp, F.; Alakus, H.; Kong, B.; Dong, Q.; et al. Inflammatory IFIT3 Renders Chemotherapy Resistance by Regulating Post-Translational Modification of VDAC2 in Pancreatic Cancer. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7178–7192.

- Chin, H.S.; Li, M.X.; Tan, I.K.L.; Ninnis, R.L.; Reljic, B.; Scicluna, K.; Dagley, L.F.; Sandow, J.J.; Kelly, G.L.; Samson, A.L.; et al. VDAC2 Enables BAX to Mediate Apoptosis and Limit Tumor Development. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4976.

- Hua, Q.; Zhang, B.; Xu, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Lin, Z.; Yu, D.; Ren, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, L.; et al. CEMIP, a Novel Adaptor Protein of OGT, Promotes Colorectal Cancer Metastasis through Glutamine Metabolic Reprogramming via Reciprocal Regulation of β-Catenin. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6443–6455.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!