A fixed exchange rate, sometimes called a pegged exchange rate, is a type of exchange rate regime in which a currency's value is fixed against either the value of another single currency to a basket of other currencies or to another measure of value, such as gold. There are benefits and risks to using a fixed exchange rate. A fixed exchange rate is typically used to stabilize the value of a currency by directly fixing its value in a predetermined ratio to a different, more stable, or more internationally prevalent currency (or currencies) to which the value is pegged. In doing so, the exchange rate between the currency and its peg does not change based on market conditions, unlike flexible exchange regime. This makes trade and investments between the two currency areas easier and more predictable and is especially useful for small economies that borrow primarily in foreign currency and in which external trade forms a large part of their GDP. A fixed exchange-rate system can also be used to control the behavior of a currency, such as by limiting rates of inflation. However, in doing so, the pegged currency is then controlled by its reference value. As such, when the reference value rises or falls, it then follows that the value(s) of any currencies pegged to it will also rise and fall in relation to other currencies and commodities with which the pegged currency can be traded. In other words, a pegged currency is dependent on its reference value to dictate how its current worth is defined at any given time. In addition, according to the Mundell–Fleming model, with perfect capital mobility, a fixed exchange rate prevents a government from using domestic monetary policy to achieve macroeconomic stability. In a fixed exchange-rate system, a country’s central bank typically uses an open market mechanism and is committed at all times to buy and/or sell its currency at a fixed price in order to maintain its pegged ratio and, hence, the stable value of its currency in relation to the reference to which it is pegged. To maintain a desired exchange rate, the central bank during the depreciation of the domestic money, sells its foreign money in the reserves and buys back the domestic money. This creates an artificial demand for the domestic money, which increases its exchange rate. In case of an undesired appreciation of the domestic money, the central bank buys back the foreign money and thus flushes the domestic money into the market for decreasing the demand and exchange rate. The central bank from its reserves also provides the assets and/or the foreign currency or currencies which are needed in order to finance any imbalance of payments. In the 21st century, the currencies associated with large economies typically do not fix or peg exchange rates to other currencies. The last large economy to use a fixed exchange rate system was the People's Republic of China, which, in July 2005, adopted a slightly more flexible exchange rate system, called a managed exchange rate. The European Exchange Rate Mechanism is also used on a temporary basis to establish a final conversion rate against the euro from the local currencies of countries joining the Eurozone.

- local currencies

- monetary policy

- model

1. History

The gold standard or gold exchange standard of fixed exchange rates prevailed from about 1870 to 1914, before which many countries followed bimetallism.[1] The period between the two world wars was transitory, with the Bretton Woods system emerging as the new fixed exchange rate regime in the aftermath of World War II. It was formed with an intent to rebuild war-ravaged nations after World War II through a series of currency stabilization programs and infrastructure loans.[2] The early 1970s saw the breakdown of the system and its replacement by a mixture of fluctuating and fixed exchange rates.[3]

1.1. Chronology

Timeline of the fixed exchange rate system:[4]

| 1880–1914 | Classical gold standard period |

| April 1925 | United Kingdom returns to gold standard |

| October 1929 | United States stock market crashes |

| September 1931 | United Kingdom abandons gold standard |

| July 1944 | Bretton Woods conference |

| March 1947 | International Monetary Fund comes into being |

| August 1971 | United States suspends convertibility of dollar into gold – Bretton Woods system collapses |

| December 1971 | Smithsonian Agreement |

| March 1972 | European snake with 2.25% band of fluctuation allowed |

| March 1973 | Managed float regime comes into being |

| April 1978 | Jamaica Accords take effect |

| September 1985 | Plaza Accord |

| September 1992 | United Kingdom and Italy abandon Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) |

| August 1993 | European Monetary System allows ±15% fluctuation in exchange rates |

1.2. Gold Standard

The earliest establishment of a gold standard was in the United Kingdom in 1821 followed by Australia in 1852 and Canada in 1853. Under this system, the external value of all currencies was denominated in terms of gold with central banks ready to buy and sell unlimited quantities of gold at the fixed price. Each central bank maintained gold reserves as their official reserve asset.[5] For example, during the “classical” gold standard period (1879–1914), the U.S. dollar was defined as 0.048 troy oz. of pure gold.[6]

1.3. Bretton Woods System

Following the Second World War, the Bretton Woods system (1944–1973) replaced gold with the U.S. dollar as the official reserve asset. The regime intended to combine binding legal obligations with multilateral decision-making through the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The rules of this system were set forth in the articles of agreement of the IMF and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The system was a monetary order intended to govern currency relations among sovereign states, with the 44 member countries required to establish a parity of their national currencies in terms of the U.S. dollar and to maintain exchange rates within 1% of parity (a "band") by intervening in their foreign exchange markets (that is, buying or selling foreign money). The U.S. dollar was the only currency strong enough to meet the rising demands for international currency transactions, and so the United States agreed both to link the dollar to gold at the rate of $35 per ounce of gold and to convert dollars into gold at that price.[4]

Due to concerns about America's rapidly deteriorating payments situation and massive flight of liquid capital from the U.S., President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold on 15 August 1971. In December 1971, the Smithsonian Agreement paved the way for the increase in the value of the dollar price of gold from US$35.50 to US$38 an ounce. Speculation against the dollar in March 1973 led to the birth of the independent float, thus effectively terminating the Bretton Woods system.[4]

1.4. Current Monetary Regimes

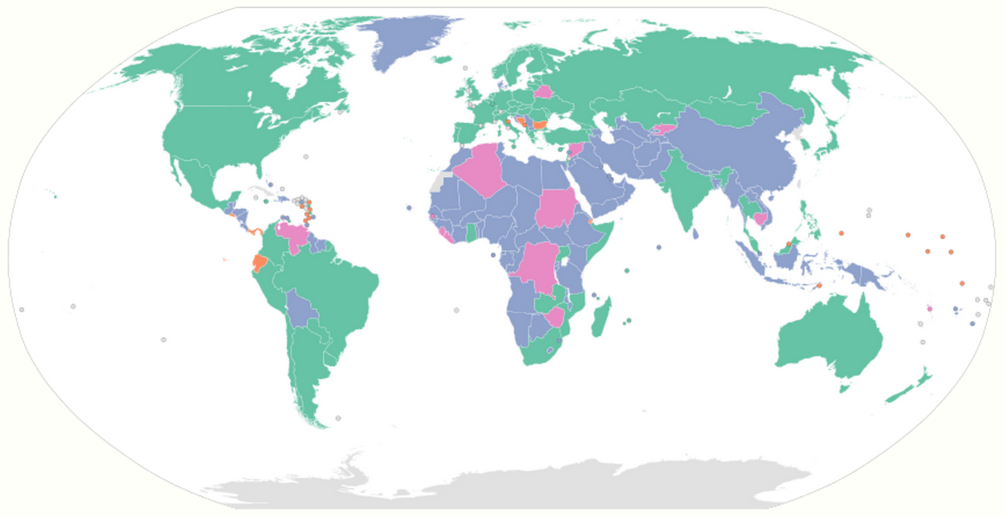

Since March 1973, the floating exchange rate has been followed and formally recognized by the Jamaica accord of 1978. Countries use foreign exchange reserves to intervene in foreign exchange markets to balance short-run fluctuations in exchange rates.[4] The prevailing exchange rate regime is often considered a revival of Bretton Woods policies, namely Bretton Woods II.[7]

2. Mechanisms

2.1. Open Market Trading

Typically, a government wanting to maintain a fixed exchange rate does so by either buying or selling its own currency on the open market.[8] This is one reason governments maintain reserves of foreign currencies.

If the exchange rate drifts too far above the fixed benchmark rate (it is stronger than required), the government sells its own currency (which increases Supply) and buys foreign currency. This causes the price of the currency to decrease in value (Read: Classical Demand-Supply diagrams). Also, if they buy the currency it is pegged to, then the price of that currency will increase, causing the relative value of the currencies to be closer to the intended relative value (unless it overshoots....)

If the exchange rate drifts too far below the desired rate, the government buys its own currency in the market by selling its reserves. This places greater demand on the market and causes the local currency to become stronger, hopefully back to its intended value. The reserves they sell may be the currency it is pegged to, in which case the value of that currency will fall.

2.2. Fiat

Another, less used means of maintaining a fixed exchange rate is by simply making it illegal to trade currency at any other rate. This is difficult to enforce and often leads to a black market in foreign currency. Nonetheless, some countries are highly successful at using this method due to government monopolies over all money conversion. This was the method employed by the Chinese government to maintain a currency peg or tightly banded float against the US dollar. China buys an average of one billion US dollars a day to maintain the currency peg.[9] Throughout the 1990s, China was highly successful at maintaining a currency peg using a government monopoly over all currency conversion between the yuan and other currencies.[10][11]

3. Open Market Mechanism Example

Under this system, the central bank first announces a fixed exchange-rate for the currency and then agrees to buy and sell the domestic currency at this value. The market equilibrium exchange rate is the rate at which supply and demand will be equal, i.e., markets will clear. In a flexible exchange rate system, this is the spot rate. In a fixed exchange-rate system, the pre-announced rate may not coincide with the market equilibrium exchange rate. The foreign central banks maintain reserves of foreign currencies and gold which they can sell in order to intervene in the foreign exchange market to make up the excess demand or take up the excess supply [12]

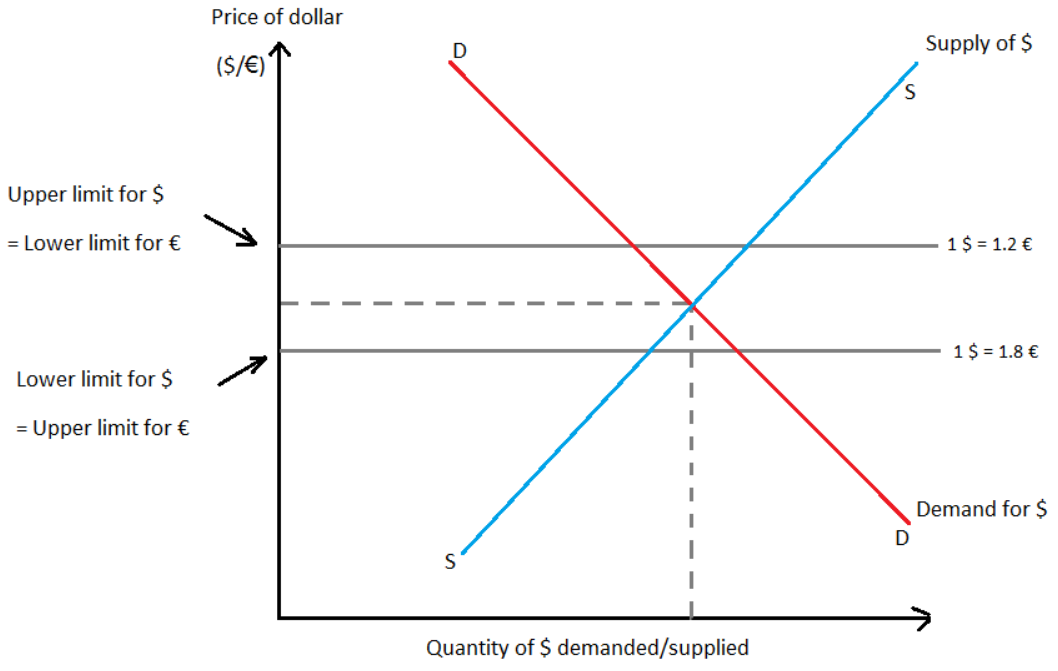

The demand for foreign exchange is derived from the domestic demand for foreign goods, services, and financial assets. The supply of foreign exchange is similarly derived from the foreign demand for goods, services, and financial assets coming from the home country. Fixed exchange-rates are not permitted to fluctuate freely or respond to daily changes in demand and supply. The government fixes the exchange value of the currency. For example, the European Central Bank (ECB) may fix its exchange rate at €1 = $1 (assuming that the euro follows the fixed exchange-rate). This is the central value or par value of the euro. Upper and lower limits for the movement of the currency are imposed, beyond which variations in the exchange rate are not permitted. The "band" or "spread" in Fig.1 is €0.6 (from €1.2 to €1.8).[13]

3.1. Excess Demand for Dollars

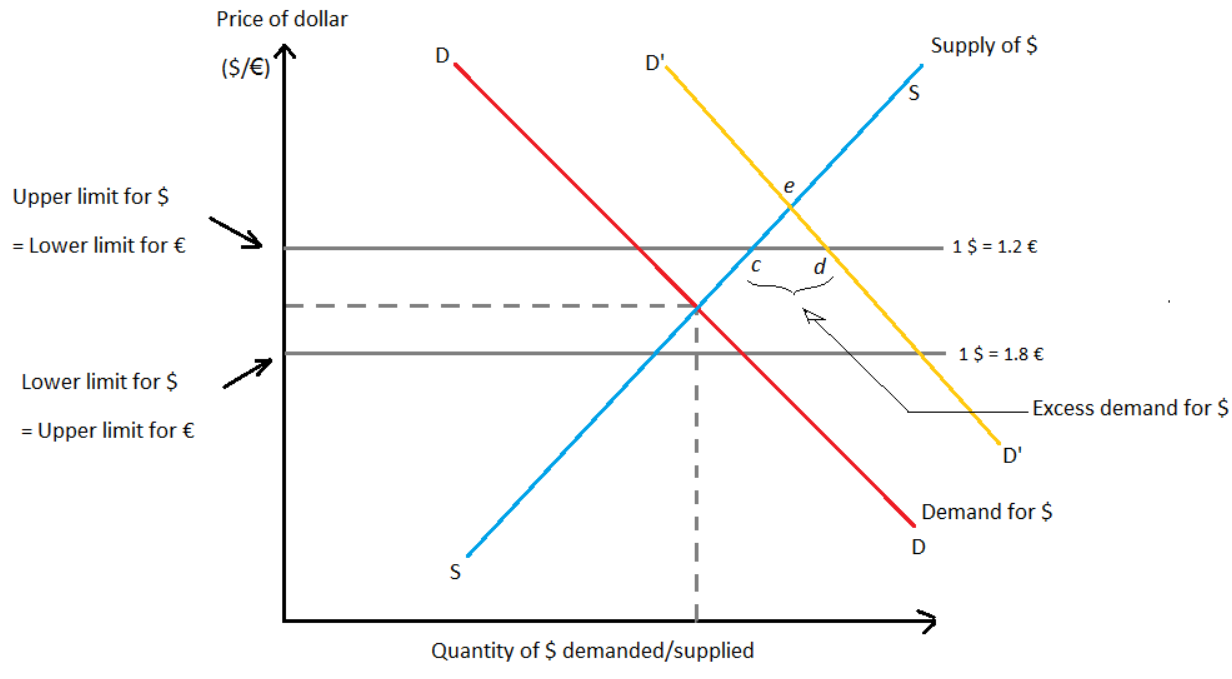

Fig.2 describes the excess demand for dollars. This is a situation where domestic demand for foreign goods, services, and financial assets exceeds the foreign demand for goods, services, and financial assets from the European Union. If the demand for dollar rises from DD to D'D', excess demand is created to the extent of cd. The ECB will sell cd dollars in exchange for euros to maintain the limit within the band. Under a floating exchange rate system, equilibrium would have been achieved at e.

When the ECB sells dollars in this manner, its official dollar reserves decline and domestic money supply shrinks. To prevent this, the ECB may purchase government bonds and thus meet the shortfall in money supply. This is called sterilized intervention in the foreign exchange market. When the ECB starts running out of reserves, it may also devalue the euro in order to reduce the excess demand for dollars, i.e., narrow the gap between the equilibrium and fixed rates.

3.2. Excess Supply of Dollars

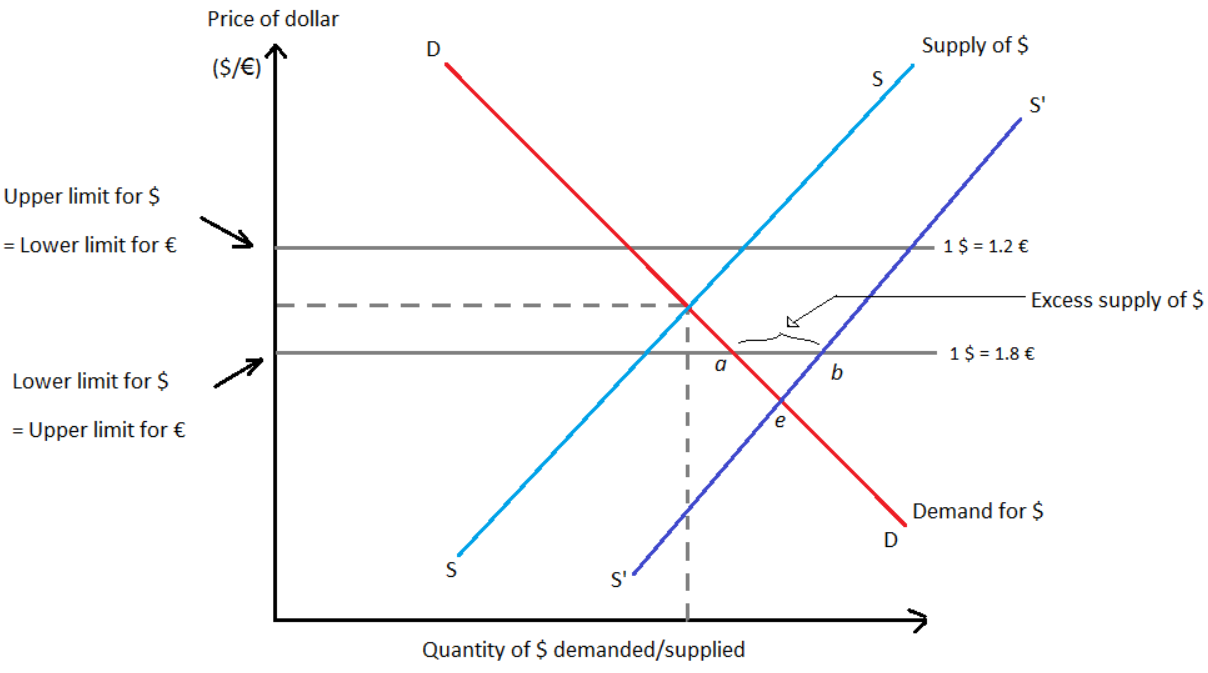

Fig.3 describes the excess supply of dollars. This is a situation where the foreign demand for goods, services, and financial assets from the European Union exceeds the European demand for foreign goods, services, and financial assets. If the supply of dollars rises from SS to S'S', excess supply is created to the extent of ab. The ECB will buy ab dollars in exchange for euros to maintain the limit within the band. Under a floating exchange rate system, equilibrium would again have been achieved at e.

When the ECB buys dollars in this manner, its official dollar reserves increase and domestic money supply expands, which may lead to inflation. To prevent this, the ECB may sell government bonds and thus counter the rise in money supply.

When the ECB starts accumulating excess reserves, it may also revalue the euro in order to reduce the excess supply of dollars, i.e., narrow the gap between the equilibrium and fixed rates. This is the opposite of devaluation.

4. Types of Fixed Exchange Rate Systems

4.1. The Gold Standard

Under the gold standard, a country’s government declares that it will exchange its currency for a certain weight in gold. In a pure gold standard, a country’s government declares that it will freely exchange currency for actual gold at the designated exchange rate. This "rule of exchange” allows anyone to enter the central bank and exchange coins or currency for pure gold or vice versa. The gold standard works on the assumption that there are no restrictions on capital movements or export of gold by private citizens across countries.

Because the central bank must always be prepared to give out gold in exchange for coin and currency upon demand, it must maintain gold reserves. Thus, this system ensures that the exchange rate between currencies remains fixed. For example, under this standard, a £1 gold coin in the United Kingdom contained 113.0016 grains of pure gold, while a $1 gold coin in the United States contained 23.22 grains. The mint parity or the exchange rate was thus: R = $/£ = 113.0016/23.22 = 4.87.[4] The main argument in favor of the gold standard is that it ties the world price level to the world supply of gold, thus preventing inflation unless there is a gold discovery (a gold rush, for example).

4.2. Price Specie Flow Mechanism

The automatic adjustment mechanism under the gold standard is the price specie flow mechanism, which operates so as to correct any balance of payments disequilibrium and adjust to shocks or changes. This mechanism was originally introduced by Richard Cantillon and later discussed by David Hume in 1752 to refute the mercantilist doctrines and emphasize that nations could not continuously accumulate gold by exporting more than their imports.

The assumptions of this mechanism are:

- Prices are flexible

- All transactions take place in gold

- There is a fixed supply of gold in the world

- Gold coins are minted at a fixed parity in each country

- There are no banks and no capital flows

Adjustment under a gold standard involves the flow of gold between countries resulting in equalization of prices satisfying purchasing power parity, and/or equalization of rates of return on assets satisfying interest rate parity at the current fixed exchange rate. Under the gold standard, each country's money supply consisted of either gold or paper currency backed by gold. Money supply would hence fall in the deficit nation and rise in the surplus nation. Consequently, internal prices would fall in the deficit nation and rise in the surplus nation, making the exports of the deficit nation more competitive than those of the surplus nations. The deficit nation's exports would be encouraged and the imports would be discouraged till the deficit in the balance of payments was eliminated.[14]

In brief:

Deficit nation: Lower money supply → Lower internal prices → More exports, less imports → Elimination of deficit

Surplus nation: Higher money supply → Higher internal prices → Less exports, more imports → Elimination of surplus

4.3. Reserve Currency Standard

In a reserve currency system, the currency of another country performs the functions that gold has in a gold standard. A country fixes its own currency value to a unit of another country’s currency, generally a currency that is prominently used in international transactions or is the currency of a major trading partner. For example, suppose India decided to fix its currency to the dollar at the exchange rate E₹/$ = 45.0. To maintain this fixed exchange rate, the Reserve Bank of India would need to hold dollars on reserve and stand ready to exchange rupees for dollars (or dollars for rupees) on demand at the specified exchange rate. In the gold standard the central bank held gold to exchange for its own currency, with a reserve currency standard it must hold a stock of the reserve currency.

Currency board arrangements are the most widespread means of fixed exchange rates. Under this, a nation rigidly pegs its currency to a foreign currency, special drawing rights (SDR) or a basket of currencies. The central bank's role in the country's monetary policy is therefore minimal as its money supply is equal to its foreign reserves. Currency boards are considered hard pegs as they allow central banks to cope with shocks to money demand without running out of reserves (11). CBAs have been operational in many nations including:

- Hong Kong (since 1983);

- Argentina (1991 to 2001);

- Estonia (1992 to 2010);

- Lithuania (1994 to 2014);

- Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 1997);

- Bulgaria (since 1997);

- Bermuda (since 1972);

- Denmark (since 1945);

- Brunei (since 1967) [15]

4.4. Gold Exchange Standard

The fixed exchange rate system set up after World War II was a gold-exchange standard, as was the system that prevailed between 1920 and the early 1930s.[16] A gold exchange standard is a mixture of a reserve currency standard and a gold standard. Its characteristics are as follows:

- All non-reserve countries agree to fix their exchange rates to the chosen reserve at some announced rate and hold a stock of reserve currency assets.

- The reserve currency country fixes its currency value to a fixed weight in gold and agrees to exchange on demand its own currency for gold with other central banks within the system, upon demand.

Unlike the gold standard, the central bank of the reserve country does not exchange gold for currency with the general public, only with other central banks.

5. Hybrid Exchange Rate Systems

The current state of foreign exchange markets does not allow for the rigid system of fixed exchange rates. At the same time, freely floating exchange rates expose a country to volatility in exchange rates. Hybrid exchange rate systems have evolved in order to combine the characteristics features of fixed and flexible exchange rate systems. They allow fluctuation of the exchange rates without completely exposing the currency to the flexibility of a free float.

5.1. Basket-of-Currencies

Countries often have several important trading partners or are apprehensive of a particular currency being too volatile over an extended period of time. They can thus choose to peg their currency to a weighted average of several currencies (also known as a currency basket) . For example, a composite currency may be created consisting of 100 Indian rupees, 100 Japanese yen and one Singapore dollar. The country creating this composite would then need to maintain reserves in one or more of these currencies to intervene in the foreign exchange market.

A popular and widely used composite currency is the SDR, which is a composite currency created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), consisting of a fixed quantity of U.S. dollars, Chinese yuan, euros, Japanese yen, and British pounds.

5.2. Crawling Pegs

In a crawling peg system a country fixes its exchange rate to another currency or basket of currencies. This fixed rate is changed from time to time at periodic intervals with a view to eliminating exchange rate volatility to some extent without imposing the constraint of a fixed rate. Crawling pegs are adjusted gradually, thus avoiding the need for interventions by the central bank (though it may still choose to do so in order to maintain the fixed rate in the event of excessive fluctuations).

5.3. Pegged within a Band

A currency is said to be pegged within a band when the central bank specifies a central exchange rate with reference to a single currency, a cooperative arrangement, or a currency composite. It also specifies a percentage allowable deviation on both sides of this central rate. Depending on the band width, the central bank has discretion in carrying out its monetary policy. The band itself may be a crawling one, which implies that the central rate is adjusted periodically. Bands may be symmetrically maintained around a crawling central parity (with the band moving in the same direction as this parity does). Alternatively, the band may be allowed to widen gradually without any pre-announced central rate.

5.4. Currency Boards

A currency board (also known as 'linked exchange rate system") effectively replaces the central bank through a legislation to fix the currency to that of another country. The domestic currency remains perpetually exchangeable for the reserve currency at the fixed exchange rate. As the anchor currency is now the basis for movements of the domestic currency, the interest rates and inflation in the domestic economy would be greatly influenced by those of the foreign economy to which the domestic currency is tied. The currency board needs to ensure the maintenance of adequate reserves of the anchor currency. It is a step away from officially adopting the anchor currency (termed as currency substitution).

5.5. Currency Substitution

This is the most extreme and rigid manner of fixing exchange rates as it entails adopting the currency of another country in place of its own. The most prominent example is the eurozone, where 19 European Union (EU) member states have adopted the euro (€) as their common currency (euroization). Their exchange rates are effectively fixed to each other.

There are similar examples of countries adopting the U.S. dollar as their domestic currency (dollarization): British Virgin Islands, Caribbean Netherlands, East Timor, Ecuador, El Salvador, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, Panama, Turks and Caicos Islands and Zimbabwe.

(See ISO 4217 for a complete list of territories by currency.)

5.6. Monetary Co-operation

Monetary co-operation is the mechanism in which two or more monetary policies or exchange rates are linked, and can happen at regional or international level.[17] The monetary co-operation does not necessarily need to be a voluntary arrangement between two countries, as it is also possible for a country to link its currency to another countries currency without the consent of the other country. Various forms of monetary co-operations exist, which range from fixed parity systems to monetary unions. Also, numerous institutions have been established to enforce monetary co-operation and to stabilise exchange rates, including the European Monetary Cooperation Fund(EMCF) in 1973[18] and the International Monetary Fund(IMF)[19]

Monetary co-operation is closely related to economic integration, and are often considered to be reinforcing processes.[20] However, economic integration is an economic arrangement between different regions, marked by the reduction or elimination of trade barriers and the coordination of monetary and fiscal policies,[21] whereas monetary co-operation is focussed on currency linkages. A monetary union is considered to be the crowning step of a process of monetary co-operation and economic integration.[20] In the form of monetary co-operation where two or more countries engage in a mutually beneficial exchange, capital among the countries involved is free to move, in contrast to capital controls.[20] Monetary co-operation is considered to promote balanced economic growth and monetary stability,[22] but can also work counter-effectively if the member countries have (strongly) differing levels of economic development.[20] Especially European and Asian countries have a history of monetary and exchange rate co-operation,[23] however the European monetary co-operation and economic integration eventually resulted in a European monetary union.

Example: The Snake

In 1973, the currencies of the European Economic Community countries, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxemburg and the Netherlands, participated in an arrangement called the Snake. This arrangement is categorized as exchange rate co-operation. During the next 6 years, this agreement allowed the currencies of the participating countries to fluctuate within a band of plus or minus 2¼% around pre-announced central rates. Later, in 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) was founded, with the participating countries in ‘the Snake’ being founding members. The EMS evolves over the next decade and even results into a truly fixed exchange rate at the start of the 1990s.[20] Around this time, in 1990, the EU introduced the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), as an umbrella term for the group of policies aimed at converging the economies of member states of the European Union over three phases [24]

Example: The Baht-U.S. Dollar Co-operation

In 1963, the Thai government established the Exchange Equalization Fund (EEF) with the purpose of playing a role in stabilizing exchange rate movements. It linked to the U.S. dollar by fixing the amount of gram of gold per baht as well as the baht per U.S. dollar. Over the course of the next 15 years, the Thai government decided to depreciate the baht in terms of gold three times, yet maintain the parity of the baht against the U.S. dollar. Due to the introduction of a new generalized floating exchange rate system by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that stretched a smaller role of gold in the international monetary system in 1978, this fixed parity system as a monetary co-operation policy was terminated. The Thai government amended its monetary policies to be more in line with the new IMF policy.[20]

6. Advantages

- A fixed exchange rate may minimize instabilities in real economic activity[25]

- Central banks can acquire credibility by fixing their country's currency to that of a more disciplined nation [25]

- On a microeconomic level, a country with poorly developed or illiquid money markets may fix their exchange rates to provide its residents with a synthetic money market with the liquidity of the markets of the country that provides the vehicle currency[25]

- A fixed exchange rate reduces volatility and fluctuations in relative prices

- It eliminates exchange rate risk by reducing the associated uncertainty

- It imposes discipline on the monetary authority

- International trade and investment flows between countries are facilitated

- Speculation in the currency markets is likely to be less destabilizing under a fixed exchange rate system than it is in a flexible one, since it does not amplify fluctuations resulting from business cycles

- Fixed exchange rates impose a price discipline on nations with higher inflation rates than the rest of the world, as such a nation is likely to face persistent deficits in its balance of payments and loss of reserves [4]

- Prevent, debt monetization, or fiscal spending financed by debt that the monetary authority buys up. This prevents high inflation. (11)

7. Disadvantages

The main criticism of a fixed exchange rate is that flexible exchange rates serve to adjust the balance of trade.[26] When a trade deficit occurs under a floating exchange rate, there will be increased demand for the foreign (rather than domestic) currency which will push up the price of the foreign currency in terms of the domestic currency. That in turn makes the price of foreign goods less attractive to the domestic market and thus pushes down the trade deficit. Under fixed exchange rates, this automatic rebalancing does not occur.

Governments also have to invest many resources in getting the foreign reserves to pile up in order to defend the pegged exchange rate. Moreover, a government, when having a fixed rather than dynamic exchange rate, cannot use monetary or fiscal policies with a free hand. For instance, by using reflationary tools to set the economy rolling (by decreasing taxes and injecting more money in the market), the government risks running into a trade deficit. This might occur as the purchasing power of a common household increases along with inflation, thus making imports relatively cheaper.

Additionally, the stubbornness of a government in defending a fixed exchange rate when in a trade deficit will force it to use deflationary measures (increased taxation and reduced availability of money), which can lead to unemployment. Finally, other countries with a fixed exchange rate can also retaliate in response to a certain country using the currency of theirs in defending their exchange rate.

Other noted disadvantages:

- The need for a fixed exchange rate regime is challenged by the emergence of sophisticated derivatives and financial tools in recent years, which allow firms to hedge exchange rate fluctuations

- The announced exchange rate may not coincide with the market equilibrium exchange rate, thus leading to excess demand or excess supply

- The central bank needs to hold stocks of both foreign and domestic currencies at all times in order to adjust and maintain exchange rates and absorb the excess demand or supply

- Fixed exchange rate does not allow for automatic correction of imbalances in the nation's balance of payments since the currency cannot appreciate/depreciate as dictated by the market

- It fails to identify the degree of comparative advantage or disadvantage of the nation and may lead to inefficient allocation of resources throughout the world

- There exists the possibility of policy delays and mistakes in achieving external balance

- The cost of government intervention is imposed upon the foreign exchange market [4]

- Does not work well in countries with dissimilar economies and thus dissimilar economic shocks (11)

8. Fixed Exchange Rate Regime Versus Capital Control

The belief that the fixed exchange rate regime brings with it stability is only partly true, since speculative attacks tend to target currencies with fixed exchange rate regimes, and in fact, the stability of the economic system is maintained mainly through capital control. A fixed exchange rate regime should be viewed as a tool in capital control.

9. FIX Line: Trade-Off Between Symmetry of Shocks and Integration

- The trade-off between symmetry of shocks and market integration for countries contemplating a pegged currency is outlined in Feenstra and Taylor's 2015 publication "International Macroeconomics" through a model known as the FIX Line Diagram.

- This symmetry-integration diagram features two regions, divided by a 45-degree line with slope of -1. This line can shift to the left or to the right depending on extra costs or benefits of floating. The line has slope= -1 is because the larger symmetry benefits are, the less pronounced integration benefits have to be and vice versa.The right region contains countries that have positive potential for pegging, while the left region contains countries that face significant risks and deterrents to pegging.

- This diagram underscores the two main factors that drive a country to contemplate pegging a currency to another, shock symmetry and market integration. Shock symmetry can be characterized as two countries having similar demand shocks due to similar industry breakdowns and economies, while market integration is a factor of the volume of trading that occurs between member nations of the peg.

- In extreme cases, it is possible for a country to only exhibit one of these characteristics and still have positive pegging potential. For example, a country that exhibits complete symmetry of shocks but has zero market integration could benefit from fixing a currency. The opposite is true, a country that has zero symmetry of shocks but has maximum trade integration (effectively one market between member countries). *This can be viewed on an international scale as well as a local scale. For example, neighborhoods within a city would experience enormous benefits from a common currency, while poorly integrated and/or dissimilar countries are likely to face large costs.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Finance:Fixed_exchange-rate_system

References

- Bordo, Michael D.; Christl, Josef; Just, Christian; James, Harold (2004). OENB Working Paper (no. 92). http://www.oenb.at/dms/oenb/Publikationen/Volkswirtschaft/Working-Papers/2004/Working-Paper-92/fullversion/wp92_tcm16-22389.pdf.

- Cohen, Benjamin J, "Bretton Woods System", Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy

- Kreinin, Mordechai (2010). International Economics: A Policy Approach. Pearson Learning Solutions. pp. 438. ISBN 0-558-58883-2.

- Salvatore, Dominick (2004). International Economics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-81-265-1413-7.

- Bordo, Michael (1999). Gold Standard and Related Regimes: Collected Essays. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55006-8.

- White, Lawrence. Is the Gold Standard Still the Gold Standard among Monetary Systems?, CATO Institute Briefing Paper no. 100, 8 Feb 2008

- Dooley, M.; Folkerts-Landau, D.; Garber, P. (2009). "Bretton Woods Ii Still Defines the International Monetary System". Pacific Economic Review 14 (3): 297–311. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0106.2009.00453.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1468-0106.2009.00453.x

- Ellie., Tragakes, (2012). Economics for the IB Diploma (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 388. ISBN 9780521186407. OCLC 778243977. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/778243977.

- Cannon, M. (September 2016). "The Chinese Exchange Rate and Its Impact On The US Dollar". ForexWatchDog. http://www.forexwatchdog.us/p/chinese-exchange-rate.html.

- Goodman, Peter S. (2005-07-27). "Don't Expect Yuan To Rise Much, China Tells World". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/26/AR2005072600681.html. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- Griswold, Daniel (2005-06-25). "Protectionism No Fix for China's Currency". Cato Institute. http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=3946. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- Dornbusch, Rüdiger; Fisher, Stanley; Startz, Richard (2011). Macroeconomics (Eleventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-0-07-337592-2.

- O'Connell, Joan (1968). "An International Adjustment Mechanism with Fixed Exchange Rates". Economica 35 (139): 274–282. doi:10.2307/2552303. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2552303

- Cooper, R.N. (1969). International Finance. Penguin Publishers. pp. 25–37.

- Salvatore, Dominick; Dean, J; Willett,T. The Dollarisation Debate (Oxford University Press, 2003)

- Bordo, M. D.; MacDonald, R. (2003). "The inter-war gold exchange standard: Credibility and monetary independence". Journal of International Money and Finance 22: 1. doi:10.1016/S0261-5606(02)00074-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0261-5606%2802%2900074-8

- Bergsten, C. F., & Green, R. A. (2016). Overview International Monetary Cooperation: Peterson Institute for International Economics

- European Monetary Cooperation Fund on Wikipedia

- Von Mises, L. (2010). International Monetary Cooperation. Mises Daily Articles. Retrieved from https://mises.org/library/international-monetary-cooperation

- Berben, R.-P., Berk, J. M., Nitihanprapas, E., Sangsuphan, K., Puapan, P., & Sodsriwiboon, P. (2003). Requirements for successful currency regimes: The Dutch and Thai experiences: De Nederlandsche Bank

- Economic Integration on Investopedia http://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/economic-integration.asp#ixzz4OHYoIkh4

- James, H. (1996). International monetary cooperation since Bretton Woods: International Monetary Fund

- Volz, U. (2010). Introduction Prospects for Monetary Cooperation and Integration in East Asia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union on Wikipedia

- Garber, Peter M.; Svensson, Lars E. O. (1995). "The Operation and Collapse of Fixed Exchange Rate Regimes". Handbook of International Economics. 3. Elsevier. pp. 1865–1911. doi:10.1016/S1573-4404(05)80016-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS1573-4404%2805%2980016-4

- Suranovic, Steven (2008-02-14). International Finance Theory and Policy. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 504.