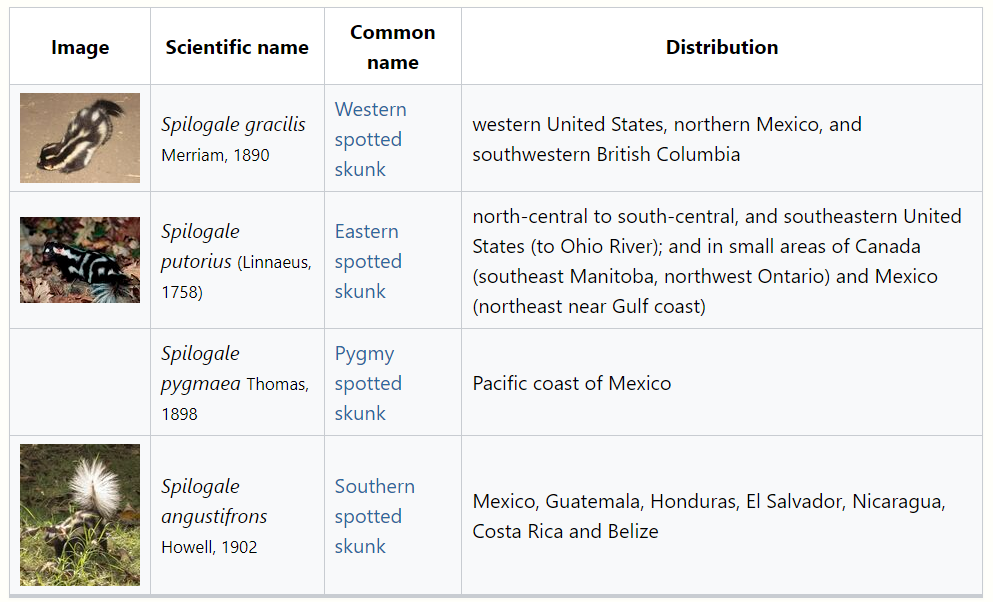

The genus Spilogale includes all skunks commonly known as spotted skunks and is composed of four extant species: S. gracilis, S. putorius, S. pygmaea, and S. angustifrons.

- spilogale

- skunks

1. Extant Species

2. Description

Mammalogists consider S. gracilis and S. putorius different species because of differences in reproductive patterns, reproductive morphology, and chromosomal variation.[1] However, interbreeding has never been disproved.[1] The name Spilogale comes from the Greek word spilo, which means "spotted", and gale, which means "weasel". Putorius is the Latin word for "fetid odor". Gracilis is the Latin word for "slender". Several other names attributed to S. putorius include: civet cat, polecat, hydrophobian skunk, phoby skunk, phoby cat, tree skunk, weasel skunk, black marten, little spotted skunk, four-lined skunk, four-striped skunk, and sachet kitty.[2]

3. Distribution and Habitat

3.1. Range

The western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis) can be found west of the Continental Divide from southern British Columbia to Central America, as well as in some parts of Montana, North Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, and western Texas. Eastward, its range borders that of the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius). Spilogale gracilis generally occupies lowland areas but they are sometimes found at higher elevations (2600 m). Although the western spotted skunk is now recognized as S. gracilis, previously, skunks west of the Cascade Crest in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon were recognized as a distinct subspecies (S. p. latifrons).[3]

Spilogale putorius is found throughout the central and southeastern United States, as well as northeastern Mexico. In Mississippi, S. putorius is found throughout the whole state, except for the northwestern corner by the Mississippi River. In the Great Plains, there has been an observed increase in the geographical range of these skunks, and the cause of this is thought to be a result of an increase in agriculture. This would lead to an increase in mice, which happen to be one of the primary prey for S. putorius.[2]

3.2. Habitat

Spilogale usually like to reside in covered thickets, woods, riparian hardwood, shrubbery, and areas that are located near streams. However, S. putorius usually enjoy staying in rocky and woody habitats that have copious amounts of vegetation. These sly creatures prefer to dwell in a den or natural cavities such as stumps or hollow logs. Spotted skunks have been found to adjust well to a wide array of dry prairie ecosystems in shallow dens. They take on a negative relationship with elevation, particularly in regions such as the Northern and Southern Appalachians of the United States. Although they have very effective digging claws, they prefer to occupy dens that are made by gophers, wood rats, pocket gophers, striped skunks, or armadillos.[3] They occupy dens that are positioned to be completely dark inside. Spilogale are very social creatures and frequently share dens with up to seven other skunks. Although skunks often live in this way, maternal dens are not open to non-maternal skunks.[2]

4. Biology

4.1. Reproduction

Around the time of March, the males’ testes begin to enlarge and are most massive by late September. The increase in size is accompanied by a larger testosterone production. Similarly, a female begins to experience an increase in ovarian activity in March. Spilogale begin to mate during March as well. Implantation occurs approximately 14–16 days after mating. For the western spotted skunk, most copulations occur in late September and the beginning of October.[4] Post copulation the zygotes are subject to normal cleavage but stop at the blastocyst stage, where they can remain in the uterus for roughly 6.5 months. After implantation, gestation last a 30 days and between April and June their offspring are born.[5] Although litter sizes vary considerably, the average litter size is about 5.5 and the gender ratio is 65 M: 35 F.[2]

4.2. Growth

The newborn skunks are covered with fine hair that shows the adult color pattern. The eyes open between 30 and 32 days.[6] The kits start solid food at about 42 days and are weaned at about two months.[2] They are full grown and reach adult size at about four months. The males do not help in raising the young.

5. Defenses

Spotted skunks protect themselves by spraying a strong and unpleasant scent. Two glands on the sides of the anus release the odorous oil through nipples. When threatened, the skunk turns its body into a U-shape with the head and anus facing the attacker. Muscles around the nipples of the scent gland aim them, giving the skunk great accuracy on targets up to 15 feet away. As a warning before spraying, the skunk stamps its front feet, raises its tail, and hisses. They may warn with a unique "hand stand"—the back vertical and the tail waving.[1]

The liquid is secreted via paired anal subcutaneous glands that are connected to the body through striated muscles. The odorous solution is emitted as an atomized spray that is nearly invisible or as streams of larger droplets.[2]

Skunks store about 1 tablespoon (15 g) of the odorous oil and can quickly spray five times in row. It takes about one week to replenish the oil.

The secretion of the spotted skunks differs from that of the striped skunks. The two major thiols of the striped skunks, (E)-2-butene-1-thiol and 3-methyl-1-butanethiol are the major components in the secretion of the spotted skunks along with a third thiol, 2-phenylethanethiol.[7]

Thioacetate derivatives of the three thiols are present in the spray of the striped skunks but not the spotted skunks. They are not as odoriferous as the thiols. Water hydrolysis converts them to the more potent thiols. This chemical conversion may be why pets that have been sprayed by skunks will have a faint "skunky" odor on damp evenings.

Spotted skunks can spray up to roughly 10 feet.

6. Deodorizing

Changing the thiols into compounds that have little or no odor can be done by oxidizing the thiols to sulfonic acids. Hydrogen peroxide and baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) are mild enough to be used on people and animals but changes hair color.

Stronger oxidizing agents, like sodium hypochlorite solutions—liquid laundry bleach—are cheap and effective for deodorizing other materials.

7. Diet

Skunks are omnivorous and will eat small rodents, fruits, berries, birds, eggs, insects and larvae, lizards, snakes, and carrion. Their diet may vary with the seasons as food availability fluctuates.[2] They have a keen sense of smell that helps them find grubs and other food. Their hearing is acute but they have poor vision.

8. Life Expectancy

Spotted skunks can live 10 years in captivity, but in the wild, about half the skunks die after 1 or 2 years.

9. Conservation

The eastern spotted skunk, S. putorius, is a conservation concern. Management is hampered by an overall lack of information from surveying.[8] During the 1940s, Spilogale populations seemingly crashed and the species is currently listed by various state agencies as endangered, threatened, or ‘of concern’ across much of its range.[9] The species S. pygmaea is endemic to the Mexican Pacific coast and is currently threatened.[10] The tropical dry forest of western Mexico, where these skunks live, is a highly threatened ecosystem that has been placed on conservation priority. S. pygmaea is also the smallest carnivore native to Mexico as well as one of the smallest worldwide.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:Spotted_skunk

References

- Kaplan, Joyce (November 1994). "Seasonal Changes in Testicular Function and Seminal Characteristics of the Male Eastern Spotted Skunk (Spilogale putorius ambarvilus)". Journal of Mammalogy 4 (75): 1013–1020. doi:10.2307/1382484. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F1382484

- Bullock, Lindsay (December 2008). "Mammals of Mississippi". Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

- 2.0.CO;2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1644%2F1545-1410%282001%29674%3C0001%3ASG%3E2.0.CO%3B2" id="ref_3">Verts, B.J.; Carraway, Leslie N.; Kinlaw, Al (June 2001). "Spilogale gracilis". Mammalian Species 674: 1–10. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2001)674<0001:SG>2.0.CO;2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1644%2F1545-1410%282001%29674%3C0001%3ASG%3E2.0.CO%3B2

- Kaplan, J.B.; Mead, R. A. (July 1993). "2010 Influence of season on semanal characteristics, testis size and serum testosterone in the western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis)". Reproduction 98 (2): 321–326. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0980321. PMID 8410795. http://www.reproduction-online.org/content/98/2/321.short.

- Feldhamer, George (2015). Mammalogy Adaptation Diversity Ecology. 2715 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 229. ISBN 978-1-4214-1588-8.

- "Eastern Spotted Skunk". The Mammals of Texas - Online Edition. http://www.nsrl.ttu.edu/tmot1/spilputo.htm.

- Wood, William; Morgan, Christopher G.; Miller, Alison (1991). "Volatile components in defensive spray of the spotted skunk,Spilogale putorius". Journal of Chemical Ecology 17 (7): 1415–1420. doi:10.1007/BF00983773. PMID 24257801. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF00983773

- Hackett, H. (2007). "Detection Rates of Eastern Spotted Skunks (Spilogale Putorius) in Missouri and Arkansas Using Live-capture and Non-invasive Techniques". The American Midland Naturalist 158 (1): 123–131. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2007)158[123:DROESS2.0.CO;2]. https://dx.doi.org/10.1674%2F0003-0031%282007%29158%5B123%3ADROESS%5D2.0.CO%3B2

- Gompper, Matthew; Hackett, H. Mundy (May 2005). "The long-term, range-wide decline of a once common carnivore: the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius)". Animal Conservation 8 (2): 195–201. doi:10.1017/S1367943005001964. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS1367943005001964

- Cantu ́-Salazar, Lisette; Hidalgo-Mihart, Mircea G.; López-González, Carlos A.; González-Romero, Alberto (November 2005). "Diet and food resource use by the pygmy skunk (Spilogale pygmaea) in the tropical dry forest of Chamela, Mexico". Journal of Zoology 267 (3): 283–289. doi:10.1017/S0952836905007417. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0952836905007417