A paternoster (/ˈpeɪtərˈnɒstər/, /ˈpɑː-/, or /ˈpæ-/) or paternoster lift is a passenger elevator which consists of a chain of open compartments (each usually designed for two persons) that move slowly in a loop up and down inside a building without stopping. Passengers can step on or off at any floor they like. The same technique is also used for filing cabinets to store large amounts of (paper) documents or for small spare parts. The much smaller belt manlift which consists of an endless belt with steps and rungs but no compartments is also sometimes called a paternoster. The name paternoster ("Our Father", the first two words of the Lord's Prayer in Latin) was originally applied to the device because the elevator is in the form of a loop and is thus similar to rosary beads used as an aid in reciting prayers. The construction of new paternosters was stopped in the mid-1970s due to safety concerns, but public sentiment has kept many of the remaining examples open. By far most remaining paternosters are in Europe, with 230 examples in Germany, and 68 in the Czech Republic. Only three have been identified outside Europe: one in Malaysia, one in Sri Lanka, and another in Peru.

- paternoster

- paternosters

- passenger elevator

1. History

Peter Ellis installed the first elevators that could be described as paternoster lifts in Oriel Chambers in Liverpool in 1868.[1] Another was used in 1876 to transport parcels at the General Post Office in London.[2] In 1877, British engineer Peter Hart obtained a patent on the first paternoster.[3] In 1884, the engineering firm of J & E Hall of Dartford, Kent, installed its first "Cyclic Elevator", using Hart's patent, in a London office block.[4]

The newly built Dovenhof in Hamburg was inaugurated in 1886. The prototype of the Hamburg office buildings equipped with the latest technology also had a paternoster. This first system outside of Great Britain already had the technology that would later become common, but was still driven by steam power like the English systems.[5]

The highest paternoster lift in the world was located in Stuttgart in the 16 floor Tagblatt tower, which was completed in 1927.[6]

Paternosters were popular throughout the first half of the 20th century because they could carry more passengers than ordinary elevators. They were more common in continental Europe, especially in public buildings, than in the United Kingdom. They are relatively slow elevators, typically travelling at about 30 cm per second (approx. 1 ft per second), to facilitate getting on and off.[7]

2. Safety

Paternoster elevators are only intended for transporting people; accidents have occurred when paternosters were misused for transporting bulky items such as ladders or library trolleys.[8] The risk involved is estimated to be thirty times higher than conventional elevators; a representative of the Union of Technical Inspection Associations stated that Germany saw an average of one death per year prior to 2002, at which point many paternosters were made inaccessible to the general public.[8]

The construction of new paternosters is no longer allowed in many countries because of the high risk of accident for people who cannot use the lift properly. In 2012, an 81-year-old man was killed when he fell into the shaft of a paternoster in the Dutch city of The Hague.[9] Elderly people, disabled people, and children are the most in danger of being crushed or losing a limb.[10]

In September 1975 the paternoster in Newcastle University's Claremont Tower was taken out of service after a passenger was killed when a car left its guide rail at the top of its journey and forced the two cars ascending behind it into the winding room above.[11] In October 1988 a second non-fatal accident occurred in the same lift. A conventional lift was installed in its place in 1989-1990.

In West Germany, new paternoster installations were banned in 1974, and there was an attempt to shut down all existing installations in 1994.[3] However, there was a wave of popular resistance to the ban at that time, and to another prospective ban in 2015.[3][12] (As of 2015), Germany has 231 paternosters.[3]

In April 2006, Hitachi announced plans for a modern paternoster-style elevator with computer-controlled cars and standard elevator doors to alleviate safety concerns.[13][14] A prototype was revealed (As of February 2013).[15]

3. Surviving Examples

Many paternoster lifts have been shut down, but there are surviving examples still in use throughout the world.[16]

- In Bratislava there are at least 5 operating paternosters: Ministry of Transport and Construction, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and headquarters of Railways of the Slovak Republic,[17]

- Prague City Hall has an early twentieth century paternoster renovated in 2017.[18]

- In Prague, Czech Technical University - Faculty of electrotechnical engineering at Technická 2, Dejvice

- In Prague, Ministry of Transport (Czech Republic) head office

- In Kiel, the State Parliament building for the German state of Schleswig-Holstein has had a working paternoster since 1950.[19]

- In Berlin, the offices of the formerly communist newspaper Neues Deutschland contain a working paternoster ((As of 2018)), while those of the conservative tabloid Bild contain a 19-storey paternoster[3] that is still in use but not open to the public.[20] The Rathaus Schöneberg, including scenes with its paternoster elevator, were used to film the TV series Babylon Berlin.[21]

In the German Akedemy of Sciences in Berlin another paternoster is in use.

- In Sweden there are at least two functional Paternoster lifts (HSB-huset, Kungsholmen, Stockholm; University hospital, Umeå).

- The Arts Tower at the University of Sheffield[22] has a paternoster, which is said to be the largest in the world.[23]

- On 8 December 2017 it was announced that the paternoster in the Attenborough tower at the University of Leicester would be taken out of service as maintenance had become too expensive. This was duly put into effect shortly afterwards.[24][25]

- In the late 1990s a paternoster was still in use in a building on King Street, Manchester occupied by a branch of the Natwest bank.

- Agenda 2020 - The Albert Sloman Library at the University of Essex on the Colchester campus has a working paternoster.[26]

- In the Christiansborg Palace where the Danish parliament resides.

- In Jahn Ferenc hospital at Budapest, Hungary.

- In the offices of Czech Post at Brno railway station, Czech Republic (returned to use in 2013, having been out of service for six years)[27]

- Ceylon Electricity Board Headquarters building in Colombo, Sri Lanka

- In Cologne, the building at Hansaring 97 has a working and in-use paternoster.

- In Frankfurt, the former IG Farben Building has running and frequently used paternosters.

- In the building of the Ministry of Agriculture in Moscow, Russia.

- In Vienna, the Rathaus (city hall) and the Ringturm (headquarters of the Vienna Insurance Group) have the last two running and frequently used paternosters in the city.

- In Wrocław, Poland, Santander Bank building, Main Square. Available for employees only.

- In Košice, Technical University of Košice operates paternoster in the main building called L9 since 1972. There's another paternoster in an administrative building of U.S.Steel Košice, steel manufacturing company in Košice.

- In Finland, at the following locations:

- In Turku, Town hall in Yliopistonkatu 27.

- In Helsinki, in the office building at Hämeentie 19.

- In Helsinki, at Eduskunta, the parliament of Finland at Mannerheimintie 30.

- In Hamburg, Germany, the building at 25 Deichstraße, Speicherstadt, has a working and in-use paternoster.

- In Miskolc, Hungary, the University of Miskolc, has a working and in-use paternoster.

- Birmingham Polytechnic (now City of Birmingham University), in the UK, had a paternoster in the 70s....but the building closed in 2018.

- Birmingham Dental School had a paternoster.

4. Galler

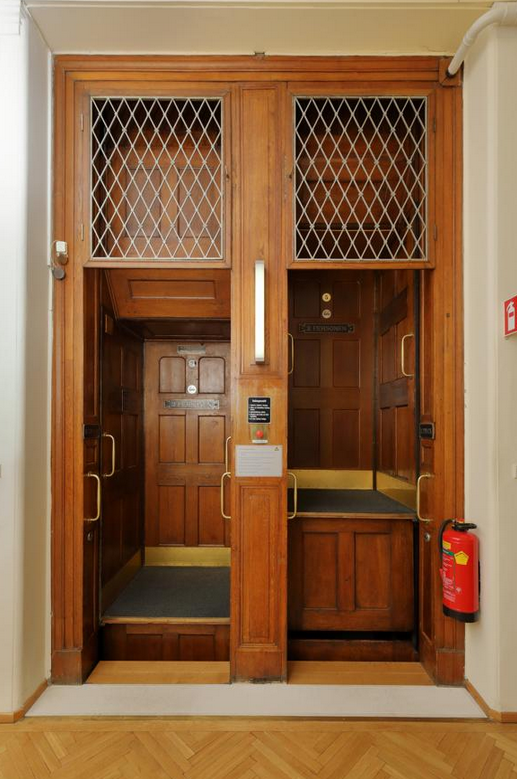

Paternoster in the House of Industry, Vienna (offices of the Federation of Austrian Industries), built c. 1910

Paternoster in Vienna City Hall, built c. 1918

Paternoster at the headquarters of Axel Springer SE

View from inside a paternoster in Berlin, showing floor slab

Paternoster machinery in the offices of the Czech Republic's Ministry of Transport, Prague

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Paternoster

References

- "In the Footsteps of Peter Ellis". 15 October 2016. http://www.liverpoolhistorysociety.org.uk/in-the-footsteps-of-peter-ellis/.

- "Paternosteraufzug". https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paternosteraufzug.

- Benoit, Bertrand (25 June 2015). "Is It Time for Germany's Doorless Elevators to Move On?". Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10907564710791284872504581068283842808972. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Hart's Cyclic Elevator Mansion House Chambers - J. and E. Hall". The Engineer: 61. 26 January 1883.

- "Paternosteraufzug". https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paternosteraufzug.

- "Paternosteraufzug". https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paternosteraufzug.

- Strakosch, George R. (1998). The vertical transportation handbook. Wiley. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-471-16291-9. https://books.google.com/?id=GLZdcTVI4kIC&pg=PA99&dq=elevator+paternoster#v=onepage&q=elevator%20paternoster&f=false. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Paternoster: Aufzug mit Charme und Risiko". Focus. Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 10 October 2006. https://www.focus.de/wissen/mensch/paternoster_aid_117131.html. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Dodelijk ongeluk liftschacht was op reünie" (in Dutch). ANP. 14 April 2012. http://www.nu.nl/binnenland/2787060/.

- "This elevator can be hazardous to your health". The Associated Press, in The Times-News. 9 July 1993. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=ic0dAAAAIBAJ&sjid=aCUEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6823,1659567&dq=fatal+paternoster&hl=en. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Knight, V (1 June 1980). "The Paternoster Lift". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers 194 (1): 131–138. doi:10.1243/PIME_PROC_1980_194_016_02. https://dx.doi.org/10.1243%2FPIME_PROC_1980_194_016_02

- Kate Connolly (14 August 2015). "Lovin' their elevator: why Germans are loopy about their revolving lifts". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/14/elevator-germans-loopy-revolving-lifts-paternosters. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Staedter, Tracy (June 2006). "Lifts in Loops". Fast Company (106): p. 35. https://www.fastcompany.com/56864/lifts-loops. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "Development of basic drive technology improve innovative transportation capacity of the elevator "circulating multi-car elevator"" (in Japanese). News Release. Hitachi. 1 March 2006. http://www.hitachi.co.jp/New/cnews/month/2006/03/0301.html. Retrieved 12 July 2010. Google translation

- "Circulating Multi-Car Elevator System "Exponential increase in carrying capacity"". Hitachi. 25 June 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPyMosdPDR4.

- Flemming, Wolfgang. "Liste laufender Paternoster (List of ongoing paternosters)" (in German). http://www.flemming-hamburg.de/patlist.htm. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- https://reality.etrend.sk/komercne-nehnutelnosti/paternostery-pat-ukrytych-pokladov-bratislavy.html

- "Prague City Hall paternoster". 2017-04-24. https://news.expats.cz/czech-tourism/restored-historic-prague-paternoster-rides-again/. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "Landtag SH - State Parliament of Schleswig-Holstein". https://www.landtag.ltsh.de/parlament/english/.

- Dullroy, Joel (23 January 2017). "Going Up: Berlin's surviving Paternoster elevators". Blogfabrik. https://blogfabrik.de/de/2017/01/23/paternoster-elevators/.

- "Im Aschinger". https://www.rbb24.de/kultur/thema/2018/babylon-berlin/beitraege/drehortkarte-babylon-berlin-aschingers-bierquellen---rathaus-schoeneberg.html.

- "The largest Paternoster elevator in the world - Doobybrain.com". Doobybrain.com. http://www.doobybrain.com/.../the-largest-paternoster-elevator-in-the-world/.

- University of Sheffield. "Campus landmarks". sheffield.ac.uk. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/visitors/landmarks.

- Hayward, Jo; Cambell, Gordon (23 June 2015). "Paternoster University of Leicester". http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02vdg1f. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Chilver, Katrina (2017-12-09). "Why students say university 'death lift' must be saved". leicestermercury. http://www.leicestermercury.co.uk/news/leicester-news/students-say-university-leicester-paternoster-901781.

- Taylor, Paul (30 August 2015). "University of Essex: Silberrad student centre review – the future imperfect revisited". The Observer.

- izi (4 August 2013). "Na poště se znovu rozběhl starý páternoster" (in Czech). Česká televize. http://www.ceskatelevize.cz/zpravodajstvi-brno/zpravy/236643-na-poste-se-znovu-rozbehl-stary-paternoster/.