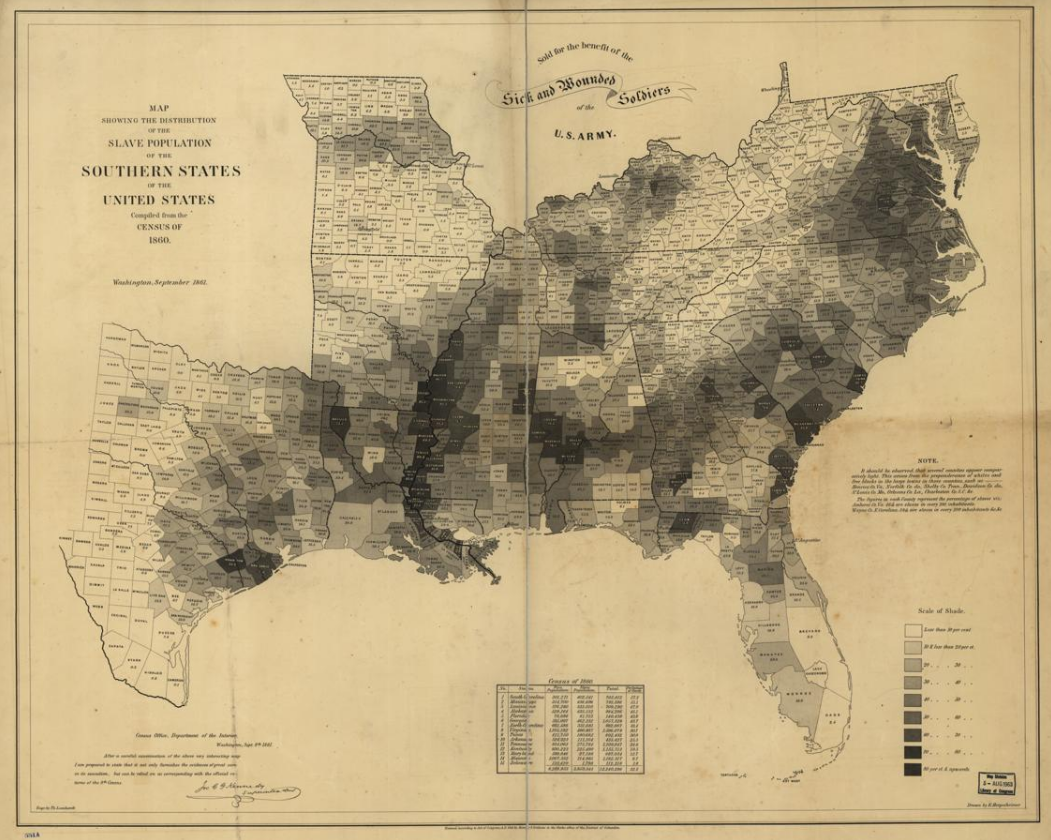

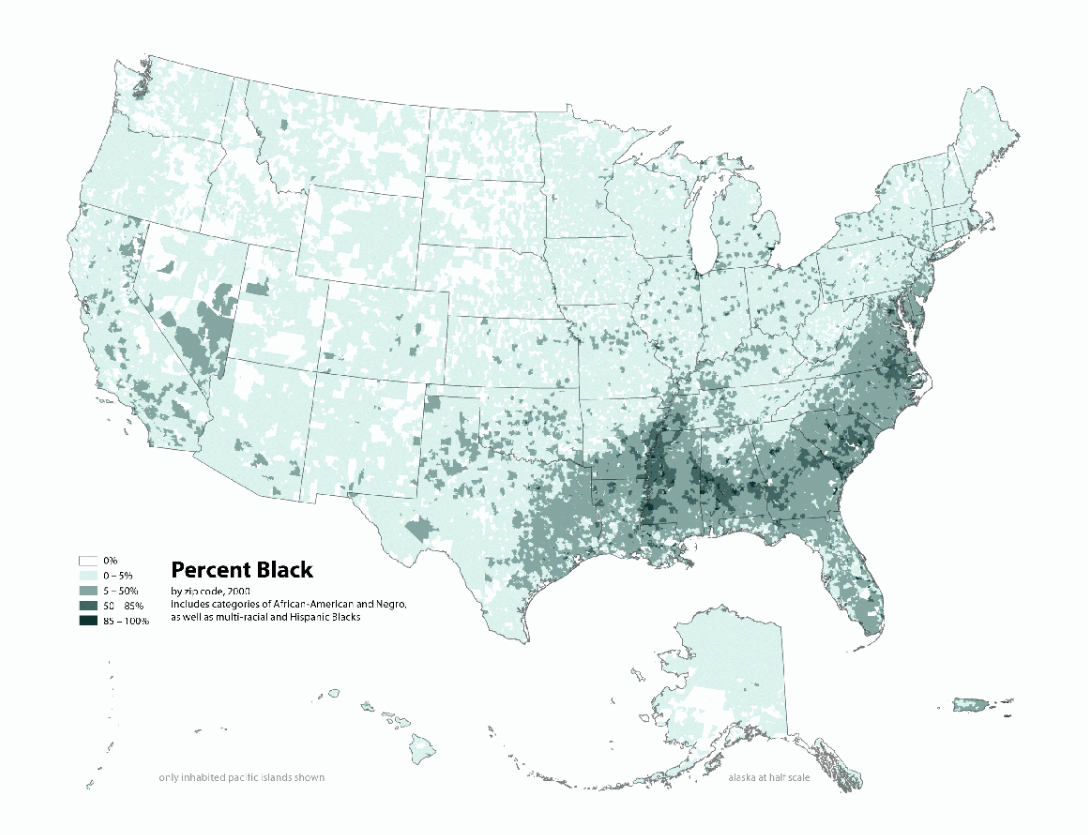

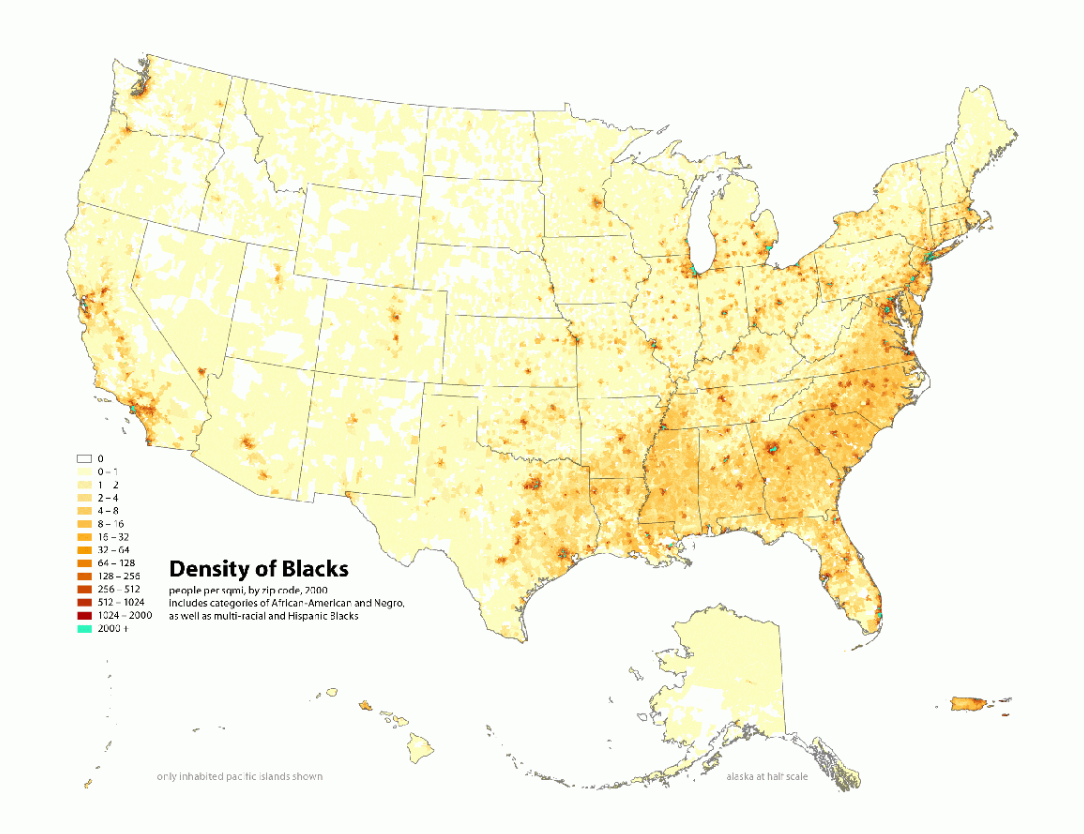

The Black Belt is a region of the Southern United States. The term originally described the prairies and dark fertile soil of central Alabama and northeast Mississippi. Because this area in the 19th century was historically developed for cotton plantations based on enslaved African American labor, the term became associated with these conditions. It was generally applied to a much larger agricultural region in the Southern United States, which was characterized by a history of cotton plantation agriculture in the 19th century and a high percentage of African Americans outside metropolitan areas. The enslaved peoples were freed after the American Civil War, and many continued to work in agriculture afterward. Their descendants make up much of the African-American population of the United States. During the first half of the 19th Century, as many as one million enslaved Africans were transported through sales in the domestic slave trade to the Deep South in a forced migration to work as laborers for the region's cotton plantations. After having lived enslaved for several generations in the area, many remained as rural workers, tenant farmers and sharecroppers after the Civil War and emancipation. Beginning in the early 20th century and up to 1970, a total of six million black people left the South in the Great Migration to find work and other opportunities in the industrial cities of the Northeast, Midwest, and West. Because of relative isolation and lack of economic development, the rural communities in the Black Belt have historically faced acute poverty, rural exodus, inadequate education programs, low educational attainment, poor health care, urban decay, substandard housing, and high levels of crime and unemployment. In December 2017, the Special Rapporteur of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights declared that Alabama was the most impoverished area in the developed world. Given the history of decades of racial segregation into the late 20th century, African-American residents have been the most disproportionately affected, although these problems apply broadly to all ethnic groups in the rural Black Belt. The region and its boundaries have varying definitions, but it is generally considered a band through the center of the Deep South, although stretching from as far north as Delaware to as far west as East Texas.

- racial segregation

- rural communities

- industrial cities

1. Definitions

Many definitions and geographic delineations of the Black Belt have been made. One of the earliest and most frequently cited is that of educator Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He wrote in his 1901 autobiography, Up from Slavery, about the Black Belt:

The term was first used to designate a part of the country which was distinguished by the color of the soil. The part of the country possessing this thick, dark, and naturally rich soil was, of course, the part of the South where the slaves were most profitable, and consequently they were taken there in the largest numbers. Later and especially since the war, the term seems to be used wholly in a political sense—that is, to designate the counties where the black people outnumber the white.

Scholar W. E. B. Du Bois also wrote about the Black Belt in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, describing the culture of rural Georgia.

Prior to the large shift of the Second Great Migration from the 1940s to the 1960s, the sociologist Arthur Raper described the Black Belt of 1936 as some 200 plantation counties where blacks represented more than 50% of the population, lying "in a crescent from Virginia to Texas".[1] The University of Alabama also classifies "roughly 200 counties" as comprising the Black Belt.[2]

The US Census reported that in 2000, the United States had ninety-six counties with a black population percentage of more than 50%. Ninety-five of these counties were located across the Coastal and Lowland South in a loose arc related to traditional areas of plantation agriculture, including the Mississippi Delta.[3]

The United States Department of Agriculture in 2000 proposed creating a federal regional commission, similar to the Appalachian Regional Commission, to address the social and economic problems of the Black Belt. It defined the region, called the Southern Black Belt, as a patchwork of 623 counties scattered throughout the South.[4][5]

2. Geology

The shape and location of the Black Belt is derived from its geology. During the Cretaceous period, about 145 to 66 million years ago, most of what are now the central plains and the southeast of the United States were covered by shallow seas. Tiny marine plankton grew in those seas, and their carbonate skeletons accumulated into massive chalk formations. That chalk eventually became a fertile soil highly suitable for growing crops. The Black Belt arc was the shoreline of one of those seas, where large amounts of chalk had collected in the shallow waters.[6]

3. History

Black Belt is still used in the physiographic sense, to describe a crescent-shaped region about 300 miles (480 km) long and up to 25 miles (40 km) wide, extending from southwest Tennessee to east-central Mississippi and then east through Alabama to the border with Georgia. Before the 19th century, this region was a mosaic of prairies and oak-hickory forest.[7]

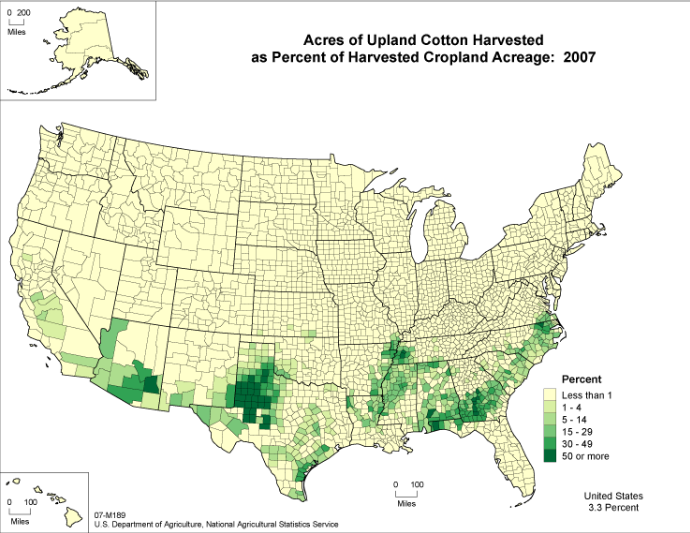

In the 1820s and 1830s, the region was identified as prime land for upland cotton plantations. Short-staple cotton did well here, and its profitable processing was made possible by invention of the cotton gin. It grew better in the upland regions than did the long-staple cotton of the Low Country. Ambitious migrant planters moved to the area in a land rush called Alabama Fever. Many brought slaves with them from the Upper South, or purchased them later in the domestic slave trade, resulting in the forced migration of an estimated one million workers to the Deep South.

The Black Belt region became one of the cores of an expanding cotton plantation system that spread through much of the American Deep South. Eventually, the term Black Belt was used to describe the larger area of the South with historic ties to slave plantation agriculture and the cash crops of cotton, rice, sugar, and tobacco.

After the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1865), most freedmen continued to work on plantations, generally through a system of sharecropping. The poverty of the South and decline in agricultural prices after the war caused suffering both for planters and workers. Although this had been a richly productive region, the agricultural economy was depressed in the late 19th century; by the early 20th century, there was a general economic collapse of the region. Among its many causes were continued depressed cotton prices, over-reliance on agriculture, soil erosion and depletion, the boll weevil invasion and subsequent collapse of the cotton economy, and the socially repressive Jim Crow laws.

With the decline of agriculture in generating wealth, what had been one of the nation's wealthiest and most politically powerful regions became one of the poorest. But, after regaining power in the state legislatures and ending Reconstruction (1863-1877), at the end of the 19th century white Southern Democrats in the former Confederate States of America completed disfranchising most blacks and many poor whites by passing new constitutions that provided for an array of discriminatory voter registration and electoral rules. They did not lose any seats in congressional apportionment, which was based on total state populations, despite their disfranchisement of many of their citizens. This allowed the Southern Democrats to accumulate seniority in Congress, where they acquired important committee chairmanships and exercised outsized political power for decades.

The South became a one-party region, and whites controlled all Congressional representation allocated for the full population, although in many areas, the majority of residents could not vote. Whites exercised political power outsize to their numbers, as Southern Democrats continued to have a one-party system through disfranchisement of blacks through much of the 20th century. They controlled a disproportionate number of seats in Congress, gaining seniority and thereby control of important committees. In the South and elsewhere, many states suffered malapportionment of state and congressional representatives, as rural areas had retained political control when state legislatures refused to redistrict long after demographic and economic shifts increasing population in urban areas.

Lynchings were frequent in this region as whites used violence to impose white supremacy. Rates of lynching were high at times of economic stress and, annually, when it was time to settle accounts for sharecropping. The southern states passed Jim Crow laws establishing racial segregation in public facilities.

During the first half of the 20th Century, up until 1970, a total of 6.5 million African Americans left the South in the Great Migration, which took place in two waves. They first migrated to the urban Northeast and Midwest for jobs and other opportunities during World War I and the Roaring '20s because of European immigration being cut off by the war as well as the black flight from racial violence and Jim Crow laws in the South. The second wave of the migration began shortly during World War II and lasted to 1970, as hundreds of thousands of blacks migrated to the West Coast and some other Western states for jobs related to the growing defense industries and post-World War II economic boom.

Because of Jim Crow laws and disfranchisement, African-American residents of the old Black Belt became supporters of the mid-20th-century Civil Rights Movement, seeking exercise of their constitutional rights as citizens.

4. Current Status

Black citizens have achieved many political and social gains since the late 20th century as a result of the civil rights movement, including the right to vote. But, due to the marginal rural economies, the Black Belt remains one of the nation's poorest and most distressed areas. Most of the area continues to be rural, with a diverse agricultural economy, including corn, peanut, soybean, cotton, pork and poultry production on large, industrial-scale farms. These agricultural operations are highly mechanized, requiring few workers.

There have been many changes in the social, economic, and cultural developments in the South since the late 20th century. Some blacks have considered the Black Belt as a kind of "national territory" for African Americans within the United States, and the 1970s some activists proposed self-determination in the area, up to and including the right to independence.[8]

The New Great Migration of educated blacks returning to the Black Belt since the late 20th century is not evenly distributed throughout the South. As with the earlier Great Migration, the New Great Migration is primarily directed toward cities and large urban areas, such as Atlanta, Charlotte, Houston, Dallas, Raleigh, Washington, D.C., Tampa, Virginia Beach, San Antonio, Memphis, Orlando, Nashville, Jacksonville, and so forth. [9] Primary destinations are those states with cities having the most job opportunities, especially Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee , Georgia, Florida, and Texas . [10] Other Southern states, including Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, Alabama, and Arkansas, have seen little net growth in the African-American population from return migration. [11]

The Black Belt also corresponds with several majority-minority congressional districts, including South Carolina's 6th congressional district (represented since 1993 by Jim Clyburn (D)), Georgia's 2nd congressional district (represented since 1993 by Sanford Bishop (D)), Alabama's 7th congressional district (represented since 2011 by Terri Sewell (D)), and Mississippi's 2nd congressional district (represented since 1993 by Bennie Thompson (D)).

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Place:Black_Belt_(U.S._region)

References

- Arthur Raper, "The Black Belt", Southern Spaces, 2004 http://southernspaces.org/2004/black-belt

- "Black Belt Fact Book". University of Alabama. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20071103084855/http://irhr.ua.edu/blackbelt/intro.html.

- "The Black Population", Census 2000 Brief https://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-5.pdf

- "The Southern Black Belt". http://www.rural.org/sbb/summary.html.

- "Federal Funds for the Black Belt". Economic Research Service. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120404222927/https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/ruralamerica/ra151/ra151d.pdf.

- "How Presidential Elections Are Impacted by a 100 Million Year-Old Coastline", Deep Sea News, June 2012 http://deepseanews.com/2012/06/how-presidential-elections-are-impacted-by-a-100-million-year-old-coastline/

- "Habitat: Black Belt Prairie". Mississippi State University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20071222130313/http://www.msstate.edu/org/mississippientmuseum/habitats/black.belt.prairie/BlackBeltPrairie.htm.

- Haywood, Harry (1977). For a Revolutionary Position on the Negro Question. Chicago: Liberator Press.

- William H. Frey (May 2004). "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965-to the present". Brookings Institution. brookings.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-new-great-migration-black-americans-return-to-the-south-1965-2000/

- William H. Frey (May 2004). "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965-to the present". Brookings Institution. brookings.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-new-great-migration-black-americans-return-to-the-south-1965-2000/

- William H. Frey (May 2004). "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965-to the present". Brookings Institution. brookings.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-new-great-migration-black-americans-return-to-the-south-1965-2000/