Trigonometry (from grc τρίγωνον (trígōnon) 'triangle', and μέτρον (métron) 'measure') is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. The Greeks focused on the calculation of chords, while mathematicians in India created the earliest-known tables of values for trigonometric ratios (also called trigonometric functions) such as sine. Throughout history, trigonometry has been applied in areas such as geodesy, surveying, celestial mechanics, and navigation. Trigonometry is known for its many identities. These trigonometric identities are commonly used for rewriting trigonometrical expressions with the aim to simplify an expression, to find a more useful form of an expression, or to solve an equation.

- trigonometry

- 'triangle'

- trigonometrical

1. History

Sumerian astronomers studied angle measure, using a division of circles into 360 degrees.[1] They, and later the Babylonians, studied the ratios of the sides of similar triangles and discovered some properties of these ratios but did not turn that into a systematic method for finding sides and angles of triangles. The ancient Nubians used a similar method.[2]

In the 3rd century BC, Hellenistic mathematicians such as Euclid and Archimedes studied the properties of chords and inscribed angles in circles, and they proved theorems that are equivalent to modern trigonometric formulae, although they presented them geometrically rather than algebraically. In 140 BC, Hipparchus (from Nicaea, Asia Minor) gave the first tables of chords, analogous to modern tables of sine values, and used them to solve problems in trigonometry and spherical trigonometry. In the 2nd century AD, the Greco-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy (from Alexandria, Egypt) constructed detailed trigonometric tables (Ptolemy's table of chords) in Book 1, chapter 11 of his Almagest.[3] Ptolemy used chord length to define his trigonometric functions, a minor difference from the sine convention we use today. (The value we call sin(θ) can be found by looking up the chord length for twice the angle of interest (2θ) in Ptolemy's table, and then dividing that value by two.) Centuries passed before more detailed tables were produced, and Ptolemy's treatise remained in use for performing trigonometric calculations in astronomy throughout the next 1200 years in the medieval Byzantine, Islamic, and, later, Western European worlds.

The modern sine convention is first attested in the Surya Siddhanta, and its properties were further documented by the 5th century (AD) Indian mathematician and astronomer Aryabhata.[4] These Greek and Indian works were translated and expanded by medieval Islamic mathematicians. By the 10th century, Islamic mathematicians were using all six trigonometric functions, had tabulated their values, and were applying them to problems in spherical geometry.[5][6] The Persian polymath Nasir al-Din al-Tusi has been described as the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right.[7][8][9] Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī was the first to treat trigonometry as a mathematical discipline independent from astronomy, and he developed spherical trigonometry into its present form.[10] He listed the six distinct cases of a right-angled triangle in spherical trigonometry, and in his On the Sector Figure, he stated the law of sines for plane and spherical triangles, discovered the law of tangents for spherical triangles, and provided proofs for both these laws.[11] Knowledge of trigonometric functions and methods reached Western Europe via Latin translations of Ptolemy's Greek Almagest as well as the works of Persian and Arab astronomers such as Al Battani and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.[12] One of the earliest works on trigonometry by a northern European mathematician is De Triangulis by the 15th century German mathematician Regiomontanus, who was encouraged to write, and provided with a copy of the Almagest, by the Byzantine Greek scholar cardinal Basilios Bessarion with whom he lived for several years.[13] At the same time, another translation of the Almagest from Greek into Latin was completed by the Cretan George of Trebizond.[14] Trigonometry was still so little known in 16th-century northern Europe that Nicolaus Copernicus devoted two chapters of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium to explain its basic concepts.

Driven by the demands of navigation and the growing need for accurate maps of large geographic areas, trigonometry grew into a major branch of mathematics.[15] Bartholomaeus Pitiscus was the first to use the word, publishing his Trigonometria in 1595.[16] Gemma Frisius described for the first time the method of triangulation still used today in surveying. It was Leonhard Euler who fully incorporated complex numbers into trigonometry. The works of the Scottish mathematicians James Gregory in the 17th century and Colin Maclaurin in the 18th century were influential in the development of trigonometric series.[17] Also in the 18th century, Brook Taylor defined the general Taylor series.[18]

2. Trigonometric Ratios

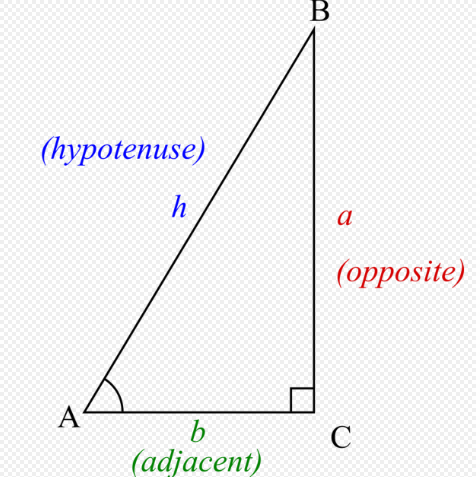

Trigonometric ratios are the ratios between edges of a right triangle. These ratios are given by the following trigonometric functions of the known angle A, where a, b and h refer to the lengths of the sides in the accompanying figure:

- Sine function (sin), defined as the ratio of the side opposite the angle to the hypotenuse.

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin A=\frac{\textrm{opposite}}{\textrm{hypotenuse}}=\frac{a}{h}. }[/math]

- Cosine function (cos), defined as the ratio of the adjacent leg (the side of the triangle joining the angle to the right angle) to the hypotenuse.

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cos A=\frac{\textrm{adjacent}}{\textrm{hypotenuse}}=\frac{b}{h}. }[/math]

- Tangent function (tan), defined as the ratio of the opposite leg to the adjacent leg.

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tan A=\frac{\textrm{opposite}}{\textrm{adjacent}}=\frac{a}{b}=\frac{a/h}{b/h}=\frac{\sin A}{\cos A}. }[/math]

The hypotenuse is the side opposite to the 90 degree angle in a right triangle; it is the longest side of the triangle and one of the two sides adjacent to angle A. The adjacent leg is the other side that is adjacent to angle A. The opposite side is the side that is opposite to angle A. The terms perpendicular and base are sometimes used for the opposite and adjacent sides respectively. See below under Mnemonics.

Since any two right triangles with the same acute angle A are similar,[19] the value of a trigonometric ratio depends only on the angle A.

The reciprocals of these functions are named the cosecant (csc), secant (sec), and cotangent (cot), respectively:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \csc A=\frac{1}{\sin A}=\frac{\textrm{hypotenuse}}{\textrm{opposite}}=\frac{h}{a} , }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sec A=\frac{1}{\cos A}=\frac{\textrm{hypotenuse}}{\textrm{adjacent}}=\frac{h}{b} , }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cot A=\frac{1}{\tan A}=\frac{\textrm{adjacent}}{\textrm{opposite}}=\frac{\cos A}{\sin A}=\frac{b}{a} . }[/math]

The cosine, cotangent, and cosecant are so named because they are respectively the sine, tangent, and secant of the complementary angle abbreviated to "co-".[20]

With these functions, one can answer virtually all questions about arbitrary triangles by using the law of sines and the law of cosines.[21] These laws can be used to compute the remaining angles and sides of any triangle as soon as two sides and their included angle or two angles and a side or three sides are known.

2.1. Mnemonics

A common use of mnemonics is to remember facts and relationships in trigonometry. For example, the sine, cosine, and tangent ratios in a right triangle can be remembered by representing them and their corresponding sides as strings of letters. For instance, a mnemonic is SOH-CAH-TOA:[22]

- Sine = Opposite ÷ Hypotenuse

- Cosine = Adjacent ÷ Hypotenuse

- Tangent = Opposite ÷ Adjacent

One way to remember the letters is to sound them out phonetically (i.e. /ˌsoʊkəˈtoʊə/ SOH-kə-TOH-ə, similar to Krakatoa).[23] Another method is to expand the letters into a sentence, such as "Some Old Hippie Caught Another Hippie Trippin' On Acid".[24]

2.2. The Unit Circle and Common Trigonometric Values

Trigonometric ratios can also be represented using the unit circle, which is the circle of radius 1 centered at the origin in the plane.[25] In this setting, the terminal side of an angle A placed in standard position will intersect the unit circle in a point (x,y), where [math]\displaystyle{ x = \cos A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y = \sin A }[/math].[25] This representation allows for the calculation of commonly found trigonometric values, such as those in the following table:[26]

| Function | 0 | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi/6 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi/4 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 3\pi/4 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 5\pi/6 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sine | [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] |

| cosine | [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -1/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{2}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{3}/2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math] |

| tangent | [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3} }[/math] | undefined | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{3} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] |

| secant | [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] | undefined | [math]\displaystyle{ -2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{2} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -2\sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math] |

| cosecant | undefined | [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] | undefined |

| cotangent | undefined | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{3}/3 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\sqrt{3} }[/math] | undefined |

3. Trigonometric Functions of Real or Complex Variables

Using the unit circle, one can extend the definitions of trigonometric ratios to all positive and negative arguments[27] (see trigonometric function).

3.1. Graphs of Trigonometric Functions

The following table summarizes the properties of the graphs of the six main trigonometric functions:[28][29]

| Function | Period | Domain | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sine | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (-\infty,\infty) }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ [-1,1] }[/math] | |

| cosine | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (-\infty,\infty) }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ [-1,1] }[/math] | |

| tangent | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ x \neq \pi/2+n\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (-\infty,\infty) }[/math] | |

| secant | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ x \neq \pi/2 + n\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (-\infty,-1] \cup [1,\infty) }[/math] | |

| cosecant | [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ x \neq n\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (-\infty,-1] \cup [1,\infty) }[/math] | |

| cotangent | [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ x \neq n\pi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ (-\infty,\infty) }[/math] |

3.2. Inverse Trigonometric Functions

Because the six main trigonometric functions are periodic, they are not injective (or, 1 to 1), and thus are not invertible. By restricting the domain of a trigonometric function, however, they can be made invertible.[30]:48ff

The names of the inverse trigonometric functions, together with their domains and range, can be found in the following table:[30]:48ff[31]:521ff

| Name | Usual notation | Definition | Domain of x for real result | Range of usual principal value (radians) |

Range of usual principal value (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| arcsine | y = arcsin(x) | x = sin(y) | −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 | −π/2 ≤ y ≤ π/2 | −90° ≤ y ≤ 90° |

| arccosine | y = arccos(x) | x = cos(y) | −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 | 0 ≤ y ≤ π | 0° ≤ y ≤ 180° |

| arctangent | y = arctan(x) | x = tan(y) | all real numbers | −π/2 < y < π/2 | −90° < y < 90° |

| arccotangent | y = arccot(x) | x = cot(y) | all real numbers | 0 < y < π | 0° < y < 180° |

| arcsecant | y = arcsec(x) | x = sec(y) | x ≤ −1 or 1 ≤ x | 0 ≤ y < π/2 or π/2 < y ≤ π | 0° ≤ y < 90° or 90° < y ≤ 180° |

| arccosecant | y = arccsc(x) | x = csc(y) | x ≤ −1 or 1 ≤ x | −π/2 ≤ y < 0 or 0 < y ≤ π/2 | −90° ≤ y < 0° or 0° < y ≤ 90° |

3.3. Power Series Representations

When considered as functions of a real variable, the trigonometric ratios can be represented by an infinite series. For instance, sine and cosine have the following representations:[32]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sin x & = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} + \cdots \\ & = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!} \\ \end{align} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \cos x & = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \frac{x^6}{6!} + \cdots \\ & = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n}}{(2n)!}. \end{align} }[/math]

With these definitions the trigonometric functions can be defined for complex numbers.[33] When extended as functions of real or complex variables, the following formula holds for the complex exponential:

- [math]\displaystyle{ e^{x+iy} = e^x(\cos y + i \sin y). }[/math]

This complex exponential function, written in terms of trigonometric functions, is particularly useful.[34][35]

3.4. Calculating Trigonometric Functions

Trigonometric functions were among the earliest uses for mathematical tables.[36] Such tables were incorporated into mathematics textbooks and students were taught to look up values and how to interpolate between the values listed to get higher accuracy.[37] Slide rules had special scales for trigonometric functions.[38]

Scientific calculators have buttons for calculating the main trigonometric functions (sin, cos, tan, and sometimes cis and their inverses).[39] Most allow a choice of angle measurement methods: degrees, radians, and sometimes gradians. Most computer programming languages provide function libraries that include the trigonometric functions.[40] The floating point unit hardware incorporated into the microprocessor chips used in most personal computers has built-in instructions for calculating trigonometric functions.[41]

4. Applications

4.1. Astronomy

For centuries, spherical trigonometry has been used for locating solar, lunar, and stellar positions,[42] predicting eclipses, and describing the orbits of the planets.[43]

In modern times, the technique of triangulation is used in astronomy to measure the distance to nearby stars,[44] as well as in satellite navigation systems.[6]

Historically, trigonometry has been used for locating latitudes and longitudes of sailing vessels, plotting courses, and calculating distances during navigation.[45]

Trigonometry is still used in navigation through such means as the Global Positioning System and artificial intelligence for autonomous vehicles.[46]

4.3. Surveying

In land surveying, trigonometry is used in the calculation of lengths, areas, and relative angles between objects.[47]

On a larger scale, trigonometry is used in geography to measure distances between landmarks.[48]

4.4. Periodic Functions

The sine and cosine functions are fundamental to the theory of periodic functions,[49] such as those that describe sound and light waves. Fourier discovered that every continuous, periodic function could be described as an infinite sum of trigonometric functions.

Even non-periodic functions can be represented as an integral of sines and cosines through the Fourier transform. This has applications to quantum mechanics[50] and communications,[51] among other fields.

4.6. Optics and Acoustics

Trigonometry is useful in many physical sciences,[52] including acoustics,[53] and optics.[53] In these areas, they are used to describe sound and light waves, and to solve boundary- and transmission-related problems.[54]

4.7. Other Applications

Other fields that use trigonometry or trigonometric functions include music theory,[55] geodesy, audio synthesis,[56] architecture,[57] electronics,[55] biology,[58] medical imaging (CT scans and ultrasound),[59] chemistry,[60] number theory (and hence cryptology),[61] seismology,[53] meteorology,[62] oceanography,[63] image compression,[64] phonetics,[65] economics,[66] electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, civil engineering,[55] computer graphics,[67] cartography,[55] crystallography[68] and game development.[67]

5. Identities

Trigonometry has been noted for its many identities, that is, equations that are true for all possible inputs.[69]

Identities involving only angles are known as trigonometric identities. Other equations, known as triangle identities,[70] relate both the sides and angles of a given triangle.

5.1. Triangle Identities

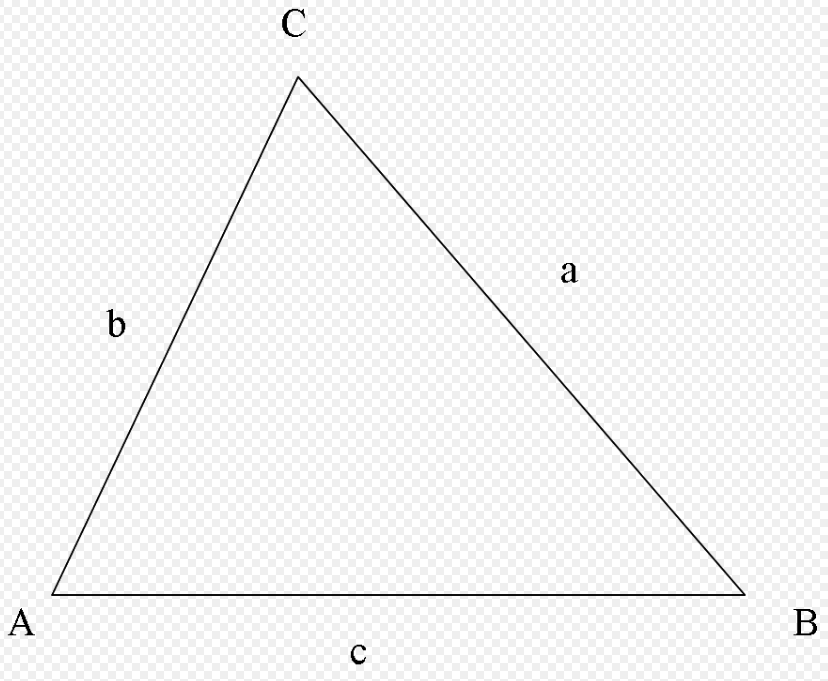

In the following identities, A, B and C are the angles of a triangle and a, b and c are the lengths of sides of the triangle opposite the respective angles (as shown in the diagram).[71]

Law of sines

The law of sines (also known as the "sine rule") for an arbitrary triangle states:[72]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{a}{\sin A} = \frac{b}{\sin B} = \frac{c}{\sin C} = 2R = \frac{abc}{2\Delta}, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math] is the area of the triangle and R is the radius of the circumscribed circle of the triangle:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R = \frac{abc}{\sqrt{(a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)(b+c-a)}}. }[/math]

Law of cosines

The law of cosines (known as the cosine formula, or the "cos rule") is an extension of the Pythagorean theorem to arbitrary triangles:[72]

- [math]\displaystyle{ c^2=a^2+b^2-2ab\cos C , }[/math]

or equivalently:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cos C=\frac{a^2+b^2-c^2}{2ab}. }[/math]

Law of tangents

The law of tangents, developed by François Viète, is an alternative to the Law of Cosines when solving for the unknown edges of a triangle, providing simpler computations when using trigonometric tables.[73] It is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{a-b}{a+b}=\frac{\tan\left[\tfrac{1}{2}(A-B)\right]}{\tan\left[\tfrac{1}{2}(A+B)\right]} }[/math]

Area

Given two sides a and b and the angle between the sides C, the area of the triangle is given by half the product of the lengths of two sides and the sine of the angle between the two sides:[72]

Heron's formula is another method that may be used to calculate the area of a triangle. This formula states that if a triangle has sides of lengths a, b, and c, and if the semiperimeter is

- [math]\displaystyle{ s=\frac{1}{2}(a+b+c), }[/math]

then the area of the triangle is:[74]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{Area} = \Delta = \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)} = \frac{abc}{4R} }[/math],

where R is the radius of the circumcircle of the triangle.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{Area} = \Delta = \frac{1}{2}a b\sin C. }[/math]

5.2. Trigonometric Identities

Pythagorean identities

The following trigonometric identities are related to the Pythagorean theorem and hold for any value:[75]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin^2 A + \cos^2 A = 1 \ }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tan^2 A + 1 = \sec^2 A \ }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \cot^2 A + 1 = \csc^2 A \ }[/math]

The second and third equations are derived from dividing the first equation by [math]\displaystyle{ \cos^2{A} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \sin^2{A} }[/math], respectively.

Euler's formula

Euler's formula, which states that [math]\displaystyle{ e^{ix} = \cos x + i \sin x }[/math], produces the following analytical identities for sine, cosine, and tangent in terms of e and the imaginary unit i:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sin x = \frac{e^{ix} - e^{-ix}}{2i}, \qquad \cos x = \frac{e^{ix} + e^{-ix}}{2}, \qquad \tan x = \frac{i(e^{-ix} - e^{ix})}{e^{ix} + e^{-ix}}. }[/math]

Other trigonometric identities

Other commonly used trigonometric identities include the half-angle identities, the angle sum and difference identities, and the product-to-sum identities.[19]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Trigonometry

References

- Pimentel, Ric; Wall, Terry (2018). Cambridge IGCSE Core Mathematics (4th ed.). Hachette UK. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-5104-2058-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=WcJWDwAAQBAJ. Extract of page 275

- Otto Neugebauer (1975). A history of ancient mathematical astronomy. 1. Springer-Verlag. p. 744. ISBN 978-3-540-06995-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=vO5FCVIxz2YC&pg=PA744.

- Toomer, G. (1998), Ptolemy's Almagest, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-00260-6

- Boyer (1991), p. 215.

- Gingerich, Owen. "Islamic astronomy." Scientific American 254.4 (1986): 74-83

- Michael Willers (13 February 2018). Armchair Algebra: Everything You Need to Know From Integers To Equations. Book Sales. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7858-3595-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=45R2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA37.

- "Nasir al-Din al-Tusi". https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Tusi_Nasir/. "One of al-Tusi's most important mathematical contributions was the creation of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right rather than as just a tool for astronomical applications. In Treatise on the quadrilateral al-Tusi gave the first extant exposition of the whole system of plane and spherical trigonometry. This work is really the first in history on trigonometry as an independent branch of pure mathematics and the first in which all six cases for a right-angled spherical triangle are set forth."

- Berggren, J. L. (October 2013). "Islamic Mathematics". the cambridge history of science. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–83. doi:10.1017/CHO9780511974007.004. ISBN 9780521594486. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/the-cambridge-history-of-science/islamic-mathematics/4BF4D143150C0013552902EE270AF9C2.

- "ṬUSI, NAṢIR-AL-DIN i. Biography". Encyclopaedia Iranica. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/tusi-nasir-al-din-bio. Retrieved 2018-08-05. "His major contribution in mathematics (Nasr, 1996, pp. 208-214) is said to be in trigonometry, which for the first time was compiled by him as a new discipline in its own right. Spherical trigonometry also owes its development to his efforts, and this includes the concept of the six fundamental formulas for the solution of spherical right-angled triangles.".

- "trigonometry". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/605281/trigonometry.

- Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- Boyer (1991), pp. 237, 274.

- "Johann Müller Regiomontanus". https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Regiomontanus/.

- N.G. Wilson (1992). From Byzantium to Italy. Greek Studies in the Italian Renaissance, London. ISBN 0-7156-2418-0

- Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (1997). The Rainbow of Mathematics: A History of the Mathematical Sciences. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32030-5.

- Robert E. Krebs (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-313-32433-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=MTXdplfiz-cC&pg=PA153.

- William Bragg Ewald (2007). From Kant to Hilbert: a source book in the foundations of mathematics. Oxford University Press US. p. 93. ISBN 0-19-850535-3 https://books.google.com/books?id=AcuF0w-Qg08C&pg=PA93

- Kelly Dempski (2002). Focus on Curves and Surfaces. p. 29. ISBN 1-59200-007-X https://books.google.com/books?id=zxdigX-KSZYC&pg=PA29

- James Stewart; Lothar Redlin; Saleem Watson (16 January 2015). Algebra and Trigonometry. Cengage Learning. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-305-53703-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=uJqaBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA448.

- Dick Jardine; Amy Shell-Gellasch (2011). Mathematical Time Capsules: Historical Modules for the Mathematics Classroom. MAA. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-88385-984-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Aa_VmrWEdvEC&pg=PA182.

- Krystle Rose Forseth; Christopher Burger; Michelle Rose Gilman; Deborah J. Rumsey (2008). Pre-Calculus For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-470-16984-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=nfwGEJaLlgsC&pg=PA218.

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "SOHCAHTOA". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SOHCAHTOA.html.

- Humble, Chris (2001). Key Maths : GCSE, Higher.. Fiona McGill. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes Publishers. p. 51. ISBN 0-7487-3396-5. OCLC 47985033. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/47985033.

- A sentence more appropriate for high schools is "'Some Old Horse Came A''Hopping Through Our Alley". Foster, Jonathan K. (2008). Memory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-280675-8.

- David Cohen; Lee B. Theodore; David Sklar (17 July 2009). Precalculus: A Problems-Oriented Approach, Enhanced Edition. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4390-4460-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=-ZXNfthUCOMC.

- W. Michael Kelley (2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Calculus. Alpha Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-02-864365-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=H-0L9Dxor6sC&pg=PA45.

- Jenny Olive (18 September 2003). Maths: A Student's Survival Guide: A Self-Help Workbook for Science and Engineering Students. Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-521-01707-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=_Ir7euRke_oC&pg=PA175.

- Mary P Attenborough (30 June 2003). Mathematics for Electrical Engineering and Computing. Elsevier. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-08-047340-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=CcwBLa1G8BUC&pg=PA418.

- Ron Larson; Bruce H. Edwards (10 November 2008). Calculus of a Single Variable. Cengage Learning. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-547-20998-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=gR7nGg5_9xcC&pg=PA21.

- Elizabeth G. Bremigan; Ralph J. Bremigan; John D. Lorch (2011). Mathematics for Secondary School Teachers. MAA. ISBN 978-0-88385-773-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=OfFEC5drTVMC&pg=PR48.

- Martin Brokate; Pammy Manchanda; Abul Hasan Siddiqi (3 August 2019). Calculus for Scientists and Engineers. Springer. ISBN 9789811384646. https://books.google.com/books?id=7DenDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA521.

- Serge Lang (14 March 2013). Complex Analysis. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-642-59273-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=0qx3BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA63.

- Silvia Maria Alessio (9 December 2015). Digital Signal Processing and Spectral Analysis for Scientists: Concepts and Applications. Springer. p. 339. ISBN 978-3-319-25468-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ja8vCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

- K. RAJA RAJESWARI; B. VISVESVARA RAO (24 March 2014). SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS. PHI Learning. p. 263. ISBN 978-81-203-4941-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=QZBeBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA263.

- John Stillwell (23 July 2010). Mathematics and Its History. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-4419-6053-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=3bE_AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA313.

- Martin Campbell-Kelly; Professor Emeritus of Computer Science Martin Campbell-Kelly; Visiting Fellow Department of Computer Science Mary Croarken; Raymond Flood; Eleanor Robson (2 October 2003). The History of Mathematical Tables: From Sumer to Spreadsheets. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-850841-0.

- George S. Donovan; Beverly Beyreuther Gimmestad (1980). Trigonometry with calculators. Prindle, Weber & Schmidt. ISBN 978-0-87150-284-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=zUruGK7TOTYC.

- Ross Raymond Middlemiss (1945). Instructions for Post-trig and Mannheim-trig Slide Rules. Frederick Post Company. https://books.google.com/books?id=OH0_AAAAYAAJ.

- "Calculator keys—what they do". Popular Science (Bonnier Corporation): 125. April 1974. https://books.google.com/books?id=1T4ORu6EICkC&pg=PA125.

- Steven S. Skiena; Miguel A. Revilla (18 April 2006). Programming Challenges: The Programming Contest Training Manual. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-387-22081-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dNoLBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA302.

- Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes: 1, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B and 3C. Intel. 2013. http://download.intel.com/products/processor/manual/325462.pdf.

- Olinthus Gregory (1816). Elements of Plane and Spherical Trigonometry: With Their Applications to Heights and Distances Projections of the Sphere, Dialling, Astronomy, the Solution of Equations, and Geodesic Operations. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. https://books.google.com/books?id=j3sAAAAAMAAJ.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1948). "Mathematical methods in ancient astronomy". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 54 (11): 1013–1041. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1948-09089-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1090%2FS0002-9904-1948-09089-9

- Michael Seeds; Dana Backman (5 January 2009). Astronomy: The Solar System and Beyond. Cengage Learning. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-495-56203-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=DajpkyXS-NUC&pg=PT254.

- John Sabine (1800). The Practical Mathematician, Containing Logarithms, Geometry, Trigonometry, Mensuration, Algebra, Navigation, Spherics and Natural Philosophy, Etc. p. 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=d_9eAAAAcAAJ&pg=PR1.

- Mordechai Ben-Ari; Francesco Mondada (2018). Elements of Robotics. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 978-3-319-62533-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=itpCDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA16.

- George Roberts Perkins (1853). Plane Trigonometry and Its Application to Mensuration and Land Surveying: Accompanied with All the Necessary Logarithmic and Trigonometric Tables. D. Appleton & Company. https://archive.org/details/planetrigonometr00perk.

- Charles W. J. Withers; Hayden Lorimer (14 December 2015). Geographers: Biobibliographical Studies. A&C Black. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4411-0785-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=eidTTrsyTr4C&pg=PA6.

- H. G. ter Morsche; J. C. van den Berg; E. M. van de Vrie (7 August 2003). Fourier and Laplace Transforms. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-521-53441-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=frT5_rfyO4IC&pg=PA61.

- Bernd Thaller (8 May 2007). Visual Quantum Mechanics: Selected Topics with Computer-Generated Animations of Quantum-Mechanical Phenomena. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-387-22770-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=GOfjBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA15.

- M. Rahman (2011). Applications of Fourier Transforms to Generalized Functions. WIT Press. ISBN 978-1-84564-564-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=k_rdcKaUdr4C.

- Lawrence Bornstein; Basic Systems, Inc (1966). Trigonometry for the Physical Sciences. Appleton-Century-Crofts. https://books.google.com/books?id=6I1GAAAAYAAJ.

- John J. Schiller; Marie A. Wurster (1988). College Algebra and Trigonometry: Basics Through Precalculus. Scott, Foresman. ISBN 978-0-673-18393-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=-CXYAAAAMAAJ.

- Dudley H. Towne (5 May 2014). Wave Phenomena. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-14515-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=uZgJCAAAQBAJ.

- E. Richard Heineman; J. Dalton Tarwater (1 November 1992). Plane Trigonometry. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-028187-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=Hi7YAAAAMAAJ.

- Mark Kahrs; Karlheinz Brandenburg (18 April 2006). Applications of Digital Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-306-47042-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=UFwKBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA404.

- Kim Williams; Michael J. Ostwald (9 February 2015). Architecture and Mathematics from Antiquity to the Future: Volume I: Antiquity to the 1500s. Birkhäuser. p. 260. ISBN 978-3-319-00137-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=fWKYBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA260.

- Dan Foulder (15 July 2019). Essential Skills for GCSE Biology. Hodder Education. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-5104-6003-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=teF6DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT78.

- Luciano Beolchi; Michael H. Kuhn (1995). Medical Imaging: Analysis of Multimodality 2D/3D Images. IOS Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-90-5199-210-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=HnRD08tDmlsC&pg=PA122.

- Marcus Frederick Charles Ladd (2014). Symmetry of Crystals and Molecules. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-967088-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=7L3DAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA13.

- Gennady I. Arkhipov; Vladimir N. Chubarikov; Anatoly A. Karatsuba (22 August 2008). Trigonometric Sums in Number Theory and Analysis. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-019798-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=G8j4Kqw45jwC.

- Study Guide for the Course in Meteorological Mathematics: Latest Revision, Feb. 1, 1943. 1943. https://books.google.com/books?id=j-ow4TBWAbcC.

- Mary Sears; Daniel Merriman; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (1980). Oceanography, the past. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90497-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z7dPAQAAIAAJ.

- "JPEG Standard (JPEG ISO/IEC 10918-1 ITU-T Recommendation T.81)". International Telecommunication Union. 1993. https://www.w3.org/Graphics/JPEG/itu-t81.pdf.

- Kirsten Malmkjaer (4 December 2009). The Routledge Linguistics Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-134-10371-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=O459AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1.

- Kamran Dadkhah (11 January 2011). Foundations of Mathematical and Computational Economics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-642-13748-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z76b-TGhs9sC&pg=PA46.

- Christopher Griffith (12 November 2012). Real-World Flash Game Development: How to Follow Best Practices AND Keep Your Sanity. CRC Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-136-13702-0. https://archive.org/details/realworldflashga0000grif.

- John Joseph Griffin (1841). A System of Crystallography, with Its Application to Mineralogy. R. Griffin. p. 119. https://archive.org/details/asystemcrystall03grifgoog.

- Dugopolski (July 2002). Trigonometry I/E Sup. Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-78666-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=_dXVeYx_kgoC.

- V&S EDITORIAL BOARD (6 January 2015). CONCISE DICTIONARY OF MATHEMATICS. V&S Publishers. p. 288. ISBN 978-93-5057-414-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=TJQ3DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA288.

- Lecture 3 | Quantum Entanglements, Part 1 (Stanford), Leonard Susskind, trigonometry in five minutes, law of sin, cos, euler formula 2006-10-09. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CaTF4QZ94Fk&t=245

- Cynthia Y. Young (19 January 2010). Precalculus. John Wiley & Sons. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-471-75684-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=9HRLAn326zEC&pg=PA435.

- Ron Larson (29 January 2010). Trigonometry. Cengage Learning. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-4390-4907-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=KzALQF4QresC&pg=PA331.

- Richard N. Aufmann; Vernon C. Barker; Richard D. Nation (5 February 2007). College Trigonometry. Cengage Learning. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-618-82507-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=s7UbEjCmJb0C&pg=PA306.

- Peterson, John C. (2004). Technical Mathematics with Calculus (illustrated ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 856. ISBN 978-0-7668-6189-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=PGuSDjHvircC. Extract of page 856