Physical engineering technology using far-infrared radiation has been gathering attention in chemical, biological, and material research fields. In particular, the high-power radiation at the terahertz region can give remarkable effects on biological materials distinct from a simple thermal treatment. Self-assembly of biological molecules such as amyloid proteins and cellulose fiber plays various roles in medical and biomaterials fields. A common characteristic of those biomolecular aggregates is a sheet-like fibrous structure that is rigid and insoluble in water, and it is often hard to manipulate the stacking conformation without heating, organic solvents, or chemical reagents.

- terahertz

- far-infrared radiation

- amyloid

- cellulose

1. Introduction

2. Promotion of Amyloid Fibrillation by the Submillimeter Wave from Gyrotron

3. Dissociation and Re-Association of Cellulose Fiber with Far-Infrared Radiation

4. Future Aspect of the Use of Far-Infrared Radiation in Biological and Material Fields

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12091326

References

- Pedersen, S.L.; Tofteng, A.P.; Malik, L.; Jensen, K.J. Microwave heating in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 41, 1826–1844.

- Horikoshi, S.; Serpone, N. Microwave Flow Chemistry as a Methodology in Organic Syntheses, Enzymatic Reactions, and Nanoparticle Syntheses. Chem. Rec. 2018, 19, 118–139.

- Wilmink, G.J.; Rivest, B.D.; Roth, C.C.; Ibey, B.L.; Payne, J.A.; Cundin, L.X.; Grundt, J.E.; Peralta, X.; Mixon, D.G.; Roach, W.P. In vitro investigation of the biological effects associated with human dermal fibroblasts exposed to 2.52 THz radiation. Lasers Surg. Med. 2010, 43, 152–163.

- Vatansever, F.; Hamblin, M.R. Far infrared radiation (FIR): Its biological effects and medical applications. Photon- Lasers Med. 2012, 1, 255–266.

- Chiang, I.N.; Pu, Y.S.; Huang, C.Y.; Young, T.H. Far infrared radiation promotes rabbit renal proximal tubule cell proliferation and functional characteristics, and protects against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180872.

- Tewari, P.; Garritano, J.; Bajwa, N.; Sung, S.; Huang, H.; Wang, D.; Grundfest, W.; Ennis, D.B.; Ruan, D.; Brown, E.; et al. Methods for registering and calibrating in vivo terahertz images of cutaneous burn wounds. Biomed. Opt. Express 2018, 10, 322–337.

- Nibali, V.C.; Havenith, M. New Insights into the Role of Water in Biological Function: Studying Solvated Biomolecules Using Terahertz Absorption Spectroscopy in Conjunction with Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12800–12807.

- Wilmink, G.J.; Grundt, J.E. Invited Review Article: Current State of Research on Biological Effects of Terahertz Radiation. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2011, 32, 1074–1122.

- Irizawa, A.; Fujimoto, M.; Kawase, K.; Kato, R.; Fujiwara, H.; Higashiya, A.; Macis, S.; Tomarchio, L.; Lupi, S.; Marcelli, A.; et al. Spatially Resolved Spectral Imaging by A THz-FEL. Condens. Matter 2020, 5, 38.

- Kawasaki, T.; Tsukiyama, K.; Irizawa, A. Dissolution of a fibrous peptide by terahertz free electron laser. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8.

- Kawasaki, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ueda, T.; Ishikawa, Y.; Yaji, T.; Ohta, T.; Tsukiyama, K.; Idehara, T.; Saiki, M.; Tani, M. Irradi-ation effect of a submillimeter wave from 420 GHz gyrotron on amyloid peptides in vitro. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 5341–5351.

- Kawasaki, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kitahara, H.; Irizawa, A.; Tani, M. Regulation of amyloid fibrils by high-power terahertz radiation. J. Jpn. Soc. Infrared Sci. Technol. 2022, 31, 52–59.

- Isoyama, G. Development of a Free-Electron Laser in the Terahertz Region. JAS4QoL 2020, 6, 1–10.

- Idehara, T.; Sabchevski, S.P.; Glyavin, M.; Mitsudo, S. The Gyrotrons as Promising Radiation Sources for THz Sensing and Imaging. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 980.

- Ryan, H.; van Bentum, J.; Maly, T. A ferromagnetic shim insert for NMR magnets – Towards an integrated gyrotron for DNP-NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 2017, 277, 1–7.

- Nanni, E.A.; Barnes, A.B.; Griffin, R.G.; Temkin, R.J. THz Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2011, 1, 145–163.

- Maly, T.; Debelouchina, G.T.; Bajaj, V.S.; Hu, K.-N.; Joo, C.-G.; Mak–Jurkauskas, M.L.; Sirigiri, J.R.; van der Wel, P.C.A.; Herzfeld, J.; Temkin, R.J.; et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization at high magnetic fields. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 052211.

- Mattsson, M.-O.; Simkó, M. Emerging medical applications based on non-ionizing electromagnetic fields from 0 Hz to 10 THz. Med. Devices-Evid. Res. 2019, 12, 347–368.

- Kok, H.P.; Cressman, E.N.K.; Ceelen, W.; Brace, C.L.; Ivkov, R.; Grüll, H.; ter Haar, G.; Wust, P.; Crezee, J. Heating technology for malignant tumors: A review. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 2020, 37, 711–741.

- Narayanan, T.; Konovalov, O. Synchrotron Scattering Methods for Nanomaterials and Soft Matter Research. Materials 2020, 13, 752.

- Squires, A.M.; Devlin, G.L.; Gras, S.L.; Tickler, A.K.; MacPhee, C.E.; Dobson, C.M. X-ray Scattering Study of the Effect of Hydration on the Cross-β Structure of Amyloid Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11738–11739.

- Iwata, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Matsuki, Y.; Akutsu, H.; Takahashi, S.; Naiki, H.; Goto, Y. 3D structure of amyloid protofilaments of β2-microglobulin fragment probed by solid-state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18119–18124.

- Bianchet, R.T.; Cubas, A.L.V.; Machado, M.M.; Moecke, E.H.S. Applicability of bacterial cellulose in cosmetics – bibliometric review. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 27, e00502.

- Chien, H.-W.; Tsai, M.-Y.; Kuo, C.-J.; Lin, C.-L. Well-Dispersed Silver Nanoparticles on Cellulose Filter Paper for Bacterial Removal. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 595.

- Qin, C.; Yao, M.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zong, Y.; Zhao, H. MFC/NFC-Based Foam/Aerogel for Production of Porous Materials: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 5568.

- Wang, X.; Yao, C.; Wang, F.; Li, Z. Cellulose-Based Nanomaterials for Energy Applications. Small 2017, 13, 42.

- Zwawi, M. A Review on Natural Fiber Bio-Composites; Surface Modifications and Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 404.

- Mazurek, S.; Mucciolo, A.; Humbel, B.M.; Nawrath, C. Transmission Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy allows simultaneous assessment of cutin and cell-wall polysaccharides of Arabidopsis petals. Plant J. 2013, 74, 880–891.

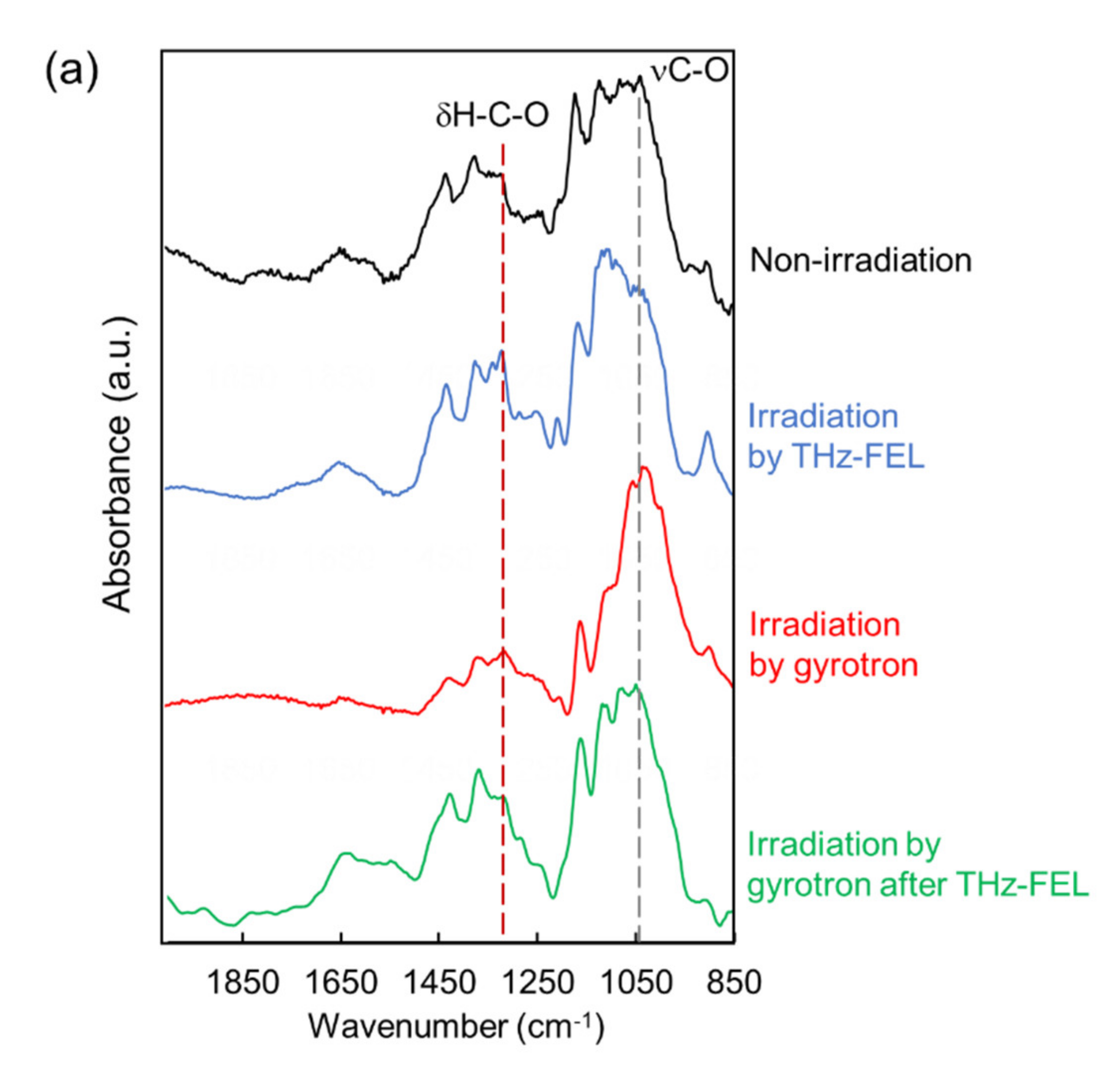

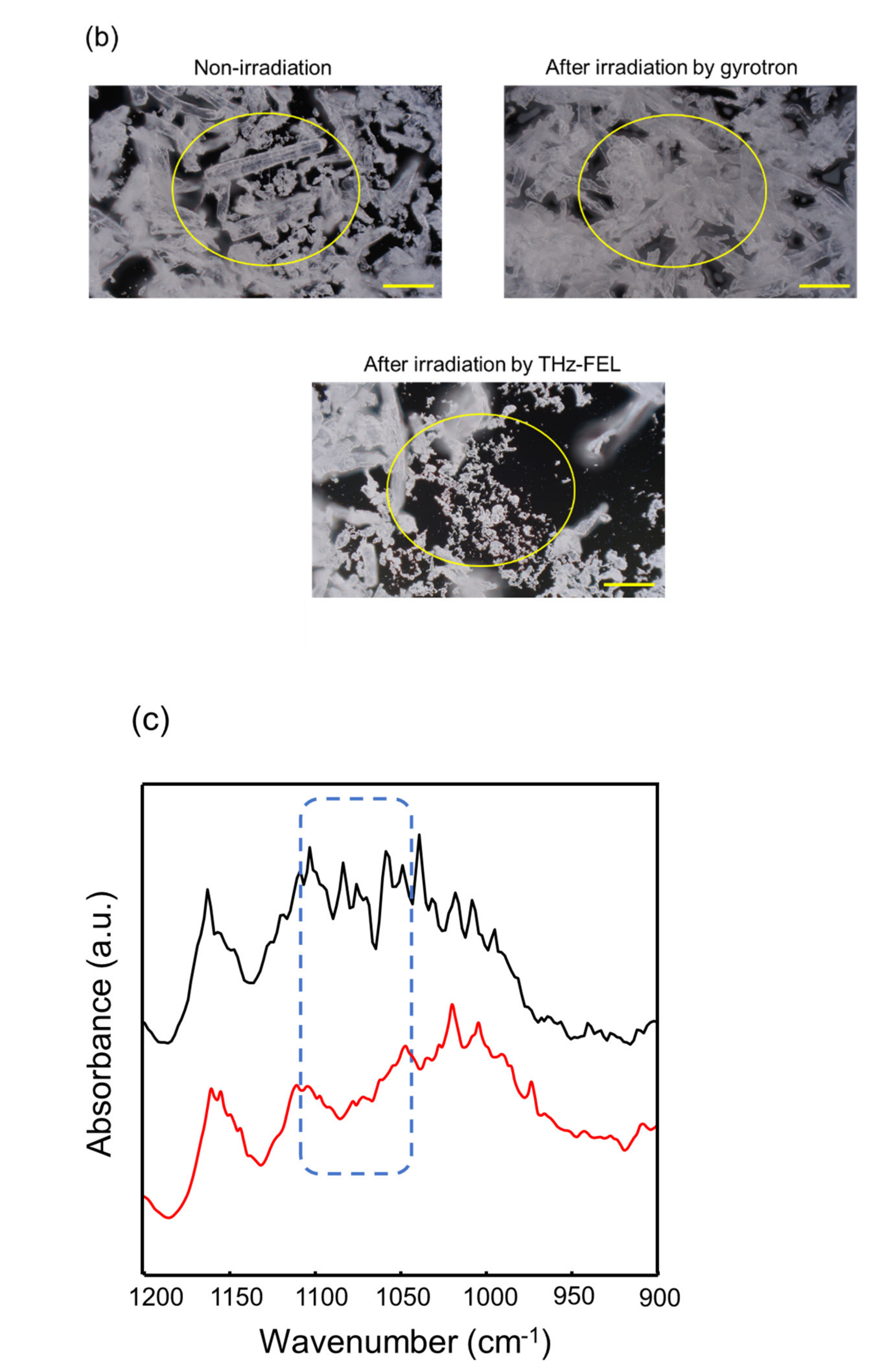

- Kawasaki, T.; Sakai, T.; Zen, H.; Sumitomo, Y.; Nogami, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Yaji, T.; Ohta, T.; Tsukiyama, K.; Hayakawa, Y. Cellulose Degradation by Infrared Free Electron Laser. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 9064–9068.

- Rockwood, D.N.; Preda, R.C.; Yücel, T.; Wang, X.; Lovett, M.L.; Kaplan, D.L. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 1612–1631.

- Bossi, A.M.; Bucciarelli, A.; Maniglio, D. Molecularly Imprinted Silk Fibroin Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 31431–31439.

- Wang, L.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Xu, B.; Martins, M. Polymeric Hydrogel Coating for Modulating the Shape of Keratin Fiber. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 749.

- Gough, C.R.; Callaway, K.; Spencer, E.; Leisy, K.; Jiang, G.; Yang, S.; Hu, X. Biopolymer-Based Filtration Materials. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11804–11812.

- Nam, K.; Maruyama, C.L.; Wang, C.-S.; Trump, B.G.; Lei, P.; Andreadis, S.T.; Baker, O.J. Laminin-111-derived peptide conjugated fibrin hydrogel restores salivary gland function. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187069.

- Besser, R.R.; Bowles, A.C.; Alassaf, A.; Carbonero, D.; Claure, I.; Jones, E.; Reda, J.; Wubker, L.; Batchelor, W.; Ziebarth, N.; et al. Enzymatically crosslinked gelatin–laminin hydrogels for applications in neuromuscular tissue engineering. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 8, 591–606.

- Schräder, C.U.; Heinz, A.; Majovsky, P.; Karaman Mayack, B.; Brinckmann, J.; Sippl, W.; Schmelzer, C.E.H. Elastin is heterogeneously cross-linked. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 15107–15119.

- Roberts, S.; Dzuricky, M.; Chilkoti, A. Elastin-like polypeptides as models of intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2477–2486.