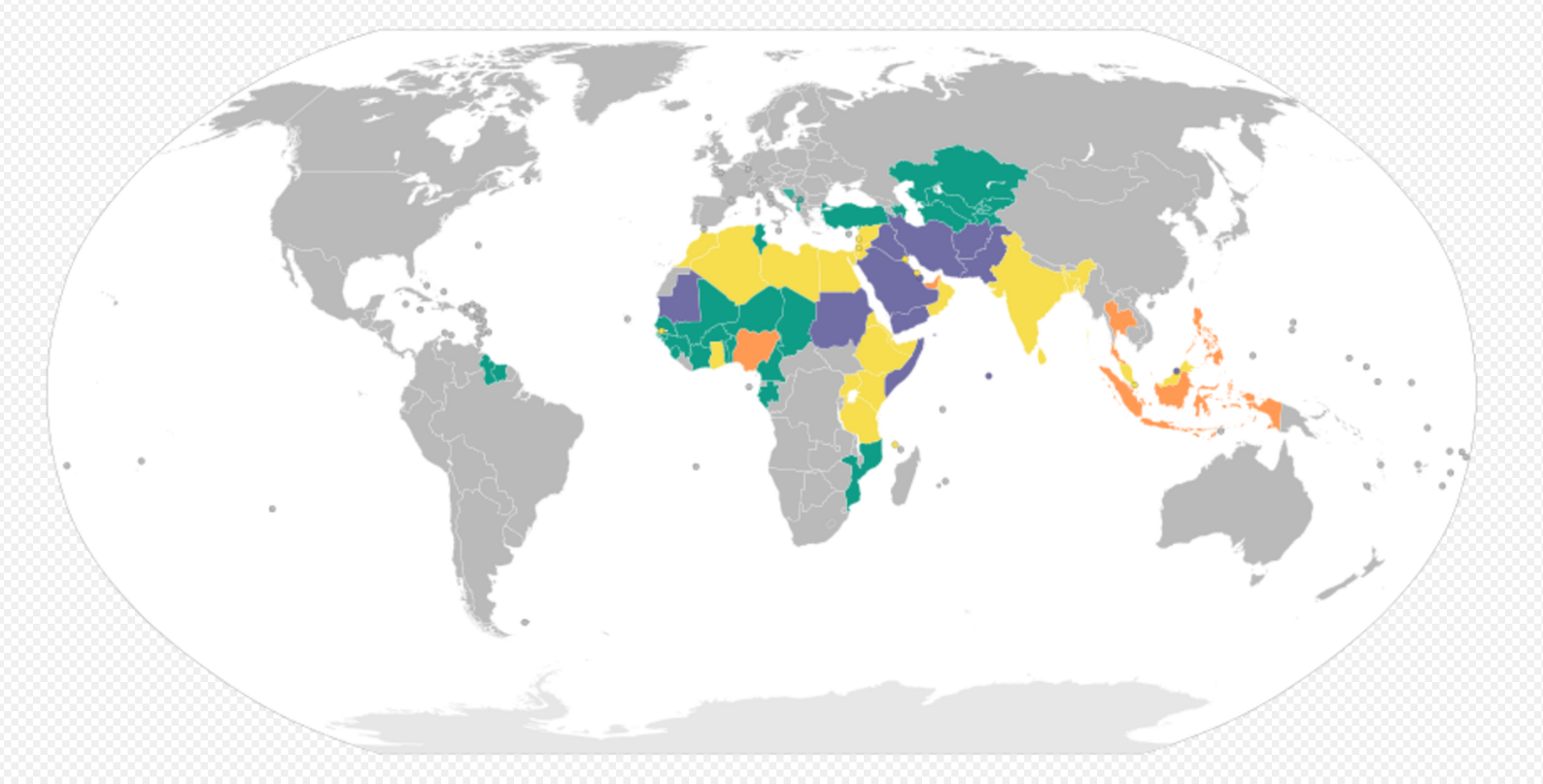

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religions beliefs and laws of Islam, or to societies where Islam is practiced. In a modern geopolitical sense, these terms refer to countries where Islam is widespread, although there are no agreed criteria for inclusion. The term Muslim-majority countries is an alternative often used for the latter sense. The history of the Muslim world spans about 1,400 years and includes a variety of socio-political developments, as well as advances in the arts, science, philosophy, and technology, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age. All Muslims look for guidance to the Quran and believe in the prophetic mission of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, but disagreements on other matters have led to the appearance of different religious schools of thought and sects within Islam. In the modern era, most of the Muslim world came under European colonial domination. The nation states that emerged in the post-colonial era have adopted a variety of political and economic models, and they have been affected by secular and as well as religious trends. (As of 2013), the combined GDP (nominal) of 49 Muslim majority countries was US$5.7 trillion, (As of 2016), they contributed 8% of the world's total. As of 2015, 1.8 billion or about 24.1% of the world population are Muslims. By the percentage of the total population in a region considering themselves Muslim, 91% in the Middle East-North Africa (MENA), 89% in Central Asia, 40% in Southeast Asia, 31% in South Asia, 30% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 25% in Asia–Oceania, around 6% in Europe, and 1% in the Americas. Most Muslims are of one of two denominations: Sunni Islam (85-90%) and Shia (10-15%), However, other denominations exist in pockets, such as Ibadi (primarily in Oman). About 13% of Muslims live in Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country; 31% of Muslims live in South Asia, the largest population of Muslims in the world; 20% in the Middle East–North Africa, where it is the dominant religion; and 15% in Sub-Saharan Africa and West Africa. Muslims are the overwhelming majority in Central Asia, the majority in the Caucasus and widespread in Southeast Asia. India is the country with the largest Muslim population outside Muslim-majority countries. Sizeable Muslim communities are also found in the Americas, China, and Europe. Islam is the fastest-growing major religion in the world.

- secular

- religion

- oman

1. Terminology

In a modern geopolitical sense, the terms 'Muslim world' and 'Islamic world' refer to countries where Islam is widespread, although there are no agreed criteria for inclusion.[1][2] Some scholars and commentators have criticised the term 'Muslim/Islamic world' and its derivative terms 'Muslim/Islamic country' as "simplistic" and "binary", since no state has a religiously homogeneous population (e.g. Egypt's citizens are c. 10% Christians), and in absolute numbers, there are sometimes fewer Muslims living in countries where they make up the majority than in countries where they form a minority.[3][4][5] Hence, the term 'Muslim-majority countries' is often preferred in literature.[6]

2. Culture

2.1. Classical Culture

-

Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni receiving a richly decorated robe of honor from the caliph al-Qadir in 1000. Miniature from the Rashid al-Din's Jami‘ al-Tawarikh. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1393133

-

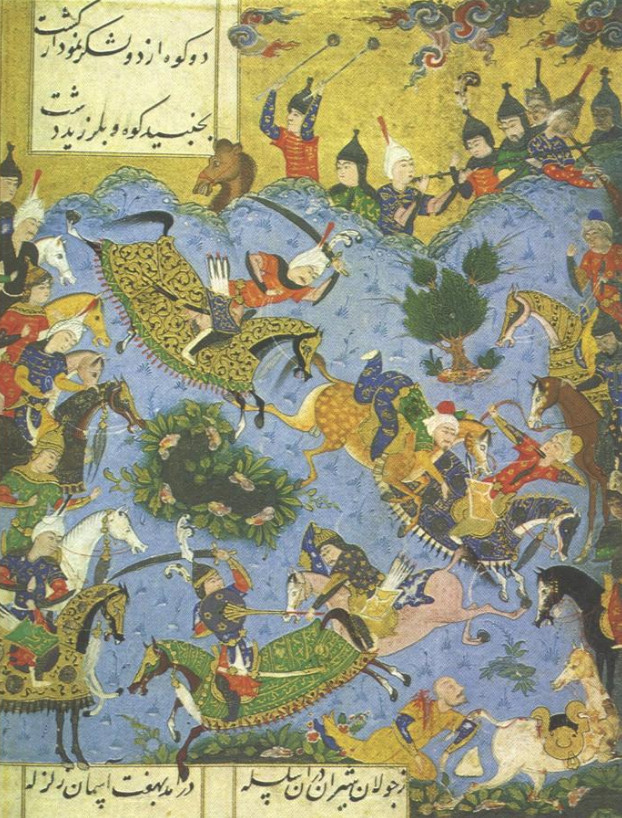

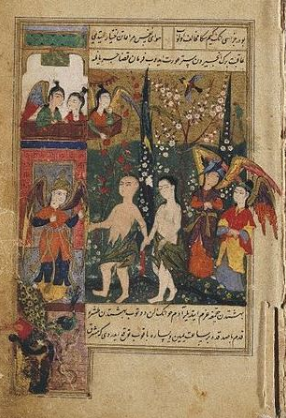

Battle between Ismail of the Safaviyya and the ruler of Shirvan, Farrukh Yassar. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1911017

-

Shah of Safavid Empire Abbas I meet with Vali Muhammad Khan. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1949004

-

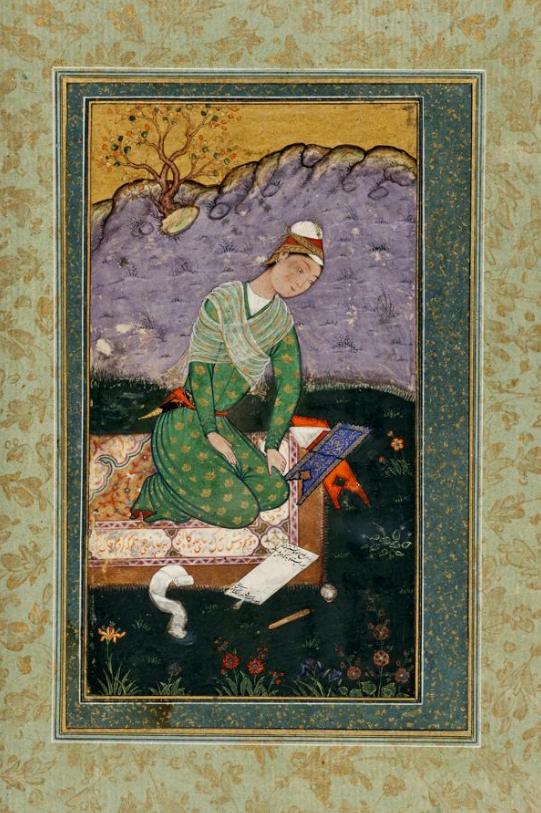

Mir Sayyid Ali, a scholar writing a commentary on the Quran, during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1426771

-

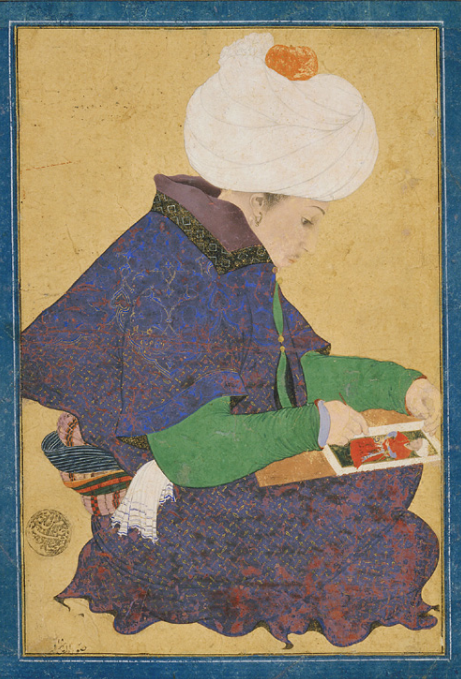

Portrait of a painter during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1865195

-

A Persian miniature of Shah Abu'l Ma‘ali, a scholar. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1732272

-

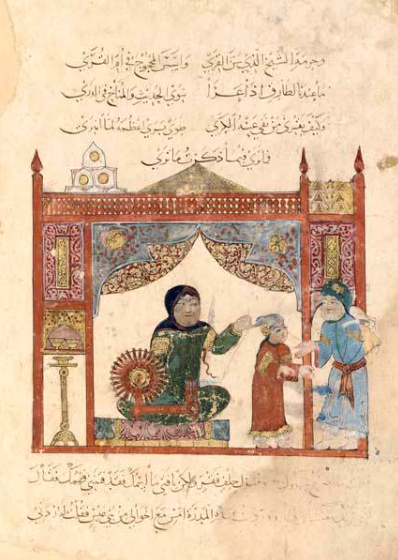

Ilkhanate Empire ruler, Ghazan, studying the Quran. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1823132

-

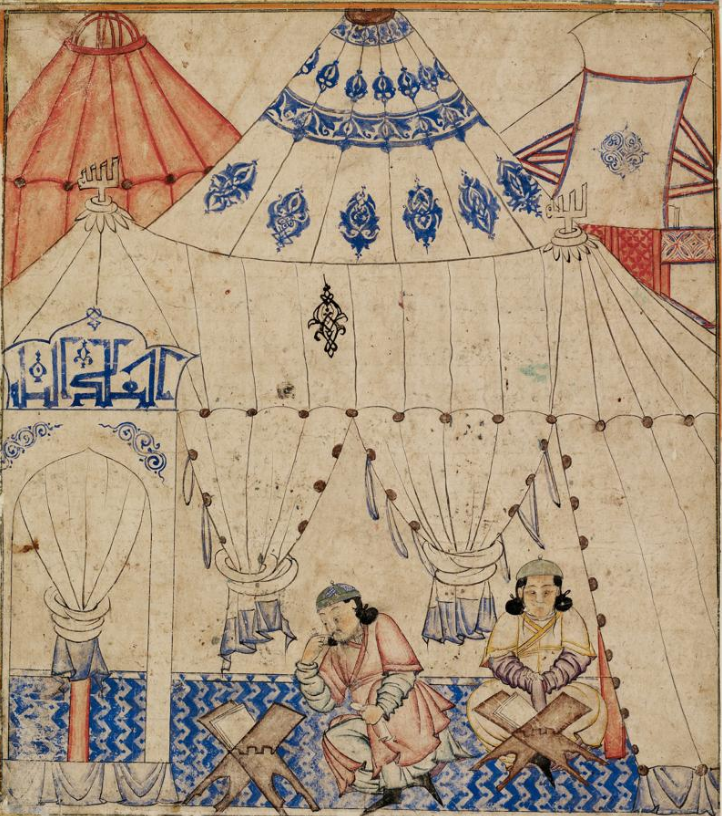

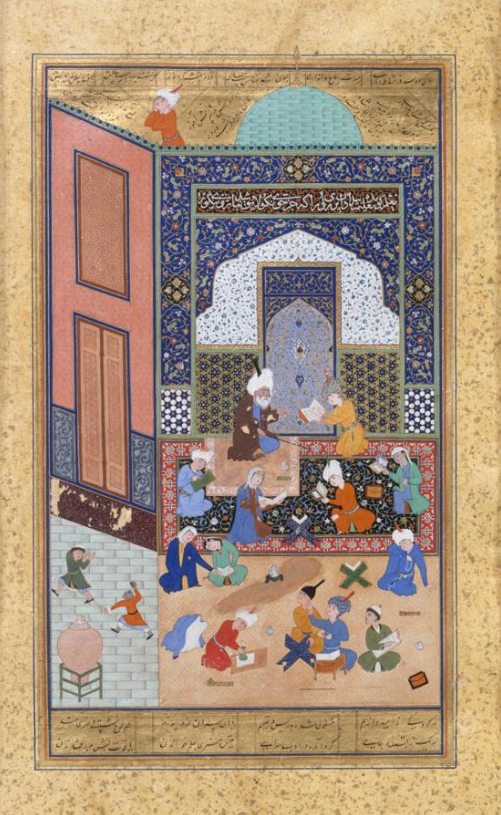

Layla and Majnun studying together, from a Persian miniature painting. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1314524

The term "Islamic Golden Age" has been attributed to a period in history wherein science, economic development and cultural works in most of the Muslim-dominated world flourished.[7][8] The age is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809) with the inauguration of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where scholars from various parts of the world sought to translate and gather all the known world's knowledge into Arabic,[9][10] and to have ended with the collapse of the Abbasid caliphate due to Mongol invasions and the Siege of Baghdad in 1258.[11] The Abbasids were influenced by the Quranic injunctions and hadiths, such as "the ink of a scholar is more holy than the blood of a martyr," that stressed the value of knowledge. The major Islamic capital cities of Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba became the main intellectual centers for science, philosophy, medicine, and education.[12] During this period, the Muslim world was a collection of cultures; they drew together and advanced the knowledge gained from the ancient Ancient Greece , Roman, Persian, Chinese, Indian, Egyptian, and Phoenician civilizations.[13]

Ceramics

Between the 8th and 18th centuries, the use of ceramic glaze was prevalent in Islamic art, usually assuming the form of elaborate pottery.[14] Tin-opacified glazing was one of the earliest new technologies developed by the Islamic potters. The first Islamic opaque glazes can be found as blue-painted ware in Basra, dating to around the 8th century. Another contribution was the development of fritware, originating from 9th-century Iraq.[15] Other centers for innovative ceramic pottery in the Old world included Fustat (from 975 to 1075), Damascus (from 1100 to around 1600) and Tabriz (from 1470 to 1550).[16]

Literature

-

Hadiqatus-suada by Oghuz Turkic poet Fuzûlî. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1886470

-

The story of Princess Parizade and the Magic Tree.[17] https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1573916

-

Cassim in the Cave by Maxfield Parrish. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1676887

-

The Magic carpet. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1530871

The best known work of fiction from the Islamic world is One Thousand and One Nights (In Persian: hezār-o-yek šab > Arabic: ʔalf-layl-at-wa-l’-layla= One thousand Night and (one) Night) or *Arabian Nights, a name invented by early Western translators, which is a compilation of folk tales from Sanskrit, Persian, and later Arabian fables. The original concept is derived from a pre-Islamic Persian prototype Hezār Afsān (Thousand Fables) that relied on particular Indian elements.[18] It reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.[19] All Arabian fantasy tales tend to be called Arabian Nights stories when translated into English, regardless of whether they appear in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights or not.[19] This work has been very influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by Antoine Galland.[20] Imitations were written, especially in France.[21] Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad the Sailor and Ali Baba.

Ibn Tufail (Abubacer) and Ibn al-Nafis were pioneers of the philosophical novel. Ibn Tufail wrote the first Arabic novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan (Philosophus Autodidactus) as a response to Al-Ghazali's The Incoherence of the Philosophers, and then Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a novel Theologus Autodidactus as a response to Ibn Tufail's Philosophus Autodidactus. Both of these narratives had protagonists (Hayy in Philosophus Autodidactus and Kamil in Theologus Autodidactus) who were autodidactic feral children living in seclusion on a desert island, both being the earliest examples of a desert island story. However, while Hayy lives alone with animals on the desert island for the rest of the story in Philosophus Autodidactus, the story of Kamil extends beyond the desert island setting in Theologus Autodidactus, developing into the earliest known coming of age plot and eventually becoming the first example of a science fiction novel.[22][23]

Theologus Autodidactus,[24][25] written by the Arabian polymath Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), is the first example of a science fiction novel.[26] It deals with various science fiction elements such as spontaneous generation, futurology, the end of the world and doomsday, resurrection, and the afterlife. Rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using the scientific knowledge of biology, astronomy, cosmology and geology known in his time. Ibn al-Nafis' fiction explained Islamic religious teachings via science and Islamic philosophy.[27]

A Latin translation of Ibn Tufail's work, Philosophus Autodidactus, first appeared in 1671, prepared by Edward Pococke the Younger, followed by an English translation by Simon Ockley in 1708, as well as German and Dutch translations. These translations might have later inspired Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe, regarded as the first novel in English.[28][29][30][31] Philosophus Autodidactus, continuing the thoughts of philosophers such as Aristotle from earlier ages, inspired Robert Boyle to write his own philosophical novel set on an island, The Aspiring Naturalist.[32]

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy,[33] derived features of and episodes about Bolgia[34] from Arabic works on Islamic eschatology:[35][36] the Hadith and the Kitab al-Miraj (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before[37] as Liber Scale Machometi[38]) concerning the ascension to Heaven of Muhammad,[39] and the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi.[40] The Moors also had a noticeable influence on the works of George Peele and William Shakespeare. Some of their works featured Moorish characters, such as Peele's The Battle of Alcazar and Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, Titus Andronicus and Othello, which featured a Moorish Othello as its title character. These works are said to have been inspired by several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England at the beginning of the 17th century.[41]

Philosophy

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of Islamic culture."[42] Islamic philosophy, in this definition is neither necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor is exclusively produced by Muslims.[42] The Persian scholar Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (980–1037) had more than 450 books attributed to him. His writings were concerned with various subjects, most notably philosophy and medicine. His medical textbook The Canon of Medicine was used as the standard text in European universities for centuries. He also wrote The Book of Healing, an influential scientific and philosophical encyclopedia.

One of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West was Averroes (Ibn Rushd), founder of the Averroism school of philosophy, whose works and commentaries affected the rise of secular thought in Europe.[43] He also developed the concept of "existence precedes essence".[44]

Another figure from the Islamic Golden Age, Avicenna, also founded his own Avicennism school of philosophy, which was influential in both Islamic and Christian lands. He was also a critic of Aristotelian logic and founder of Avicennian logic, developed the concepts of empiricism and tabula rasa, and distinguished between essence and existence.

Yet another influential philosopher who had an influence on modern philosophy was Ibn Tufail. His philosophical novel, Hayy ibn Yaqdha, translated into Latin as Philosophus Autodidactus in 1671, developed the themes of empiricism, tabula rasa, nature versus nurture,[45] condition of possibility, materialism,[46] and Molyneux's problem.[47] European scholars and writers influenced by this novel include John Locke,[48] Gottfried Leibniz,[31] Melchisédech Thévenot, John Wallis, Christiaan Huygens,[49] George Keith, Robert Barclay, the Quakers,[50] and Samuel Hartlib.[32]

Islamic philosophers continued making advances in philosophy through to the 17th century, when Mulla Sadra founded his school of Transcendent theosophy and developed the concept of existentialism.[51]

Other influential Muslim philosophers include al-Jahiz, a pioneer in evolutionary thought; Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), a pioneer of phenomenology and the philosophy of science and a critic of Aristotelian natural philosophy and Aristotle's concept of place (topos); Al-Biruni, a critic of Aristotelian natural philosophy; Ibn Tufail and Ibn al-Nafis, pioneers of the philosophical novel; Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi, founder of Illuminationist philosophy; Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, a critic of Aristotelian logic and a pioneer of inductive logic; and Ibn Khaldun, a pioneer in the philosophy of history.[52]

Sciences

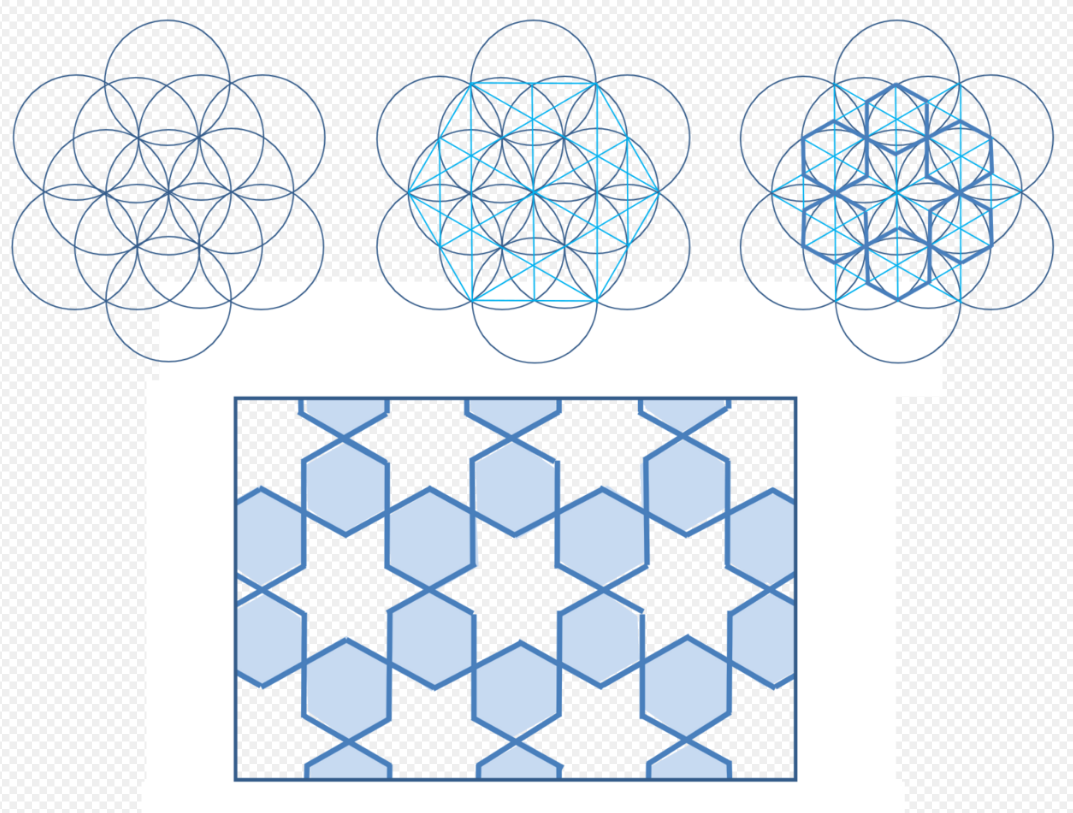

Muslim scientists placed far greater emphasis on experiment than the Greeks. This led to an early scientific method being developed in the Muslim world, where progress in methodology was made, beginning with the experiments of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) on optics from circa 1000, in his Book of Optics. The most important development of the scientific method was the use of experiments to distinguish between competing scientific theories set within a generally empirical orientation, which began among Muslim scientists. Ibn al-Haytham is also regarded as the father of optics, especially for his empirical proof of the intromission theory of light. Jim Al-Khalili stated in 2009 that Ibn al-Haytham is 'often referred to as the "world's first true scientist".'[53] al-Khwarzimi's invented the log base systems that are being used today, he also contributed theorems in trigonometry as well as limits.[54] Recent studies show that it is very likely that the Medieval Muslim artists were aware of advanced decagonal quasicrystal geometry (discovered half a millennium later in the 1970s and 1980s in the West) and used it in intricate decorative tilework in the architecture.[55]

Muslim physicians contributed to the field of medicine, including the subjects of anatomy and physiology: such as in the 15th-century Persian work by Mansur ibn Muhammad ibn al-Faqih Ilyas entitled Tashrih al-badan (Anatomy of the body) which contained comprehensive diagrams of the body's structural, nervous and circulatory systems; or in the work of the Egyptian physician Ibn al-Nafis, who proposed the theory of pulmonary circulation. Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine remained an authoritative medical textbook in Europe until the 18th century. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (also known as Abulcasis) contributed to the discipline of medical surgery with his Kitab al-Tasrif ("Book of Concessions"), a medical encyclopedia which was later translated to Latin and used in European and Muslim medical schools for centuries. Other medical advancements came in the fields of pharmacology and pharmacy.[56]

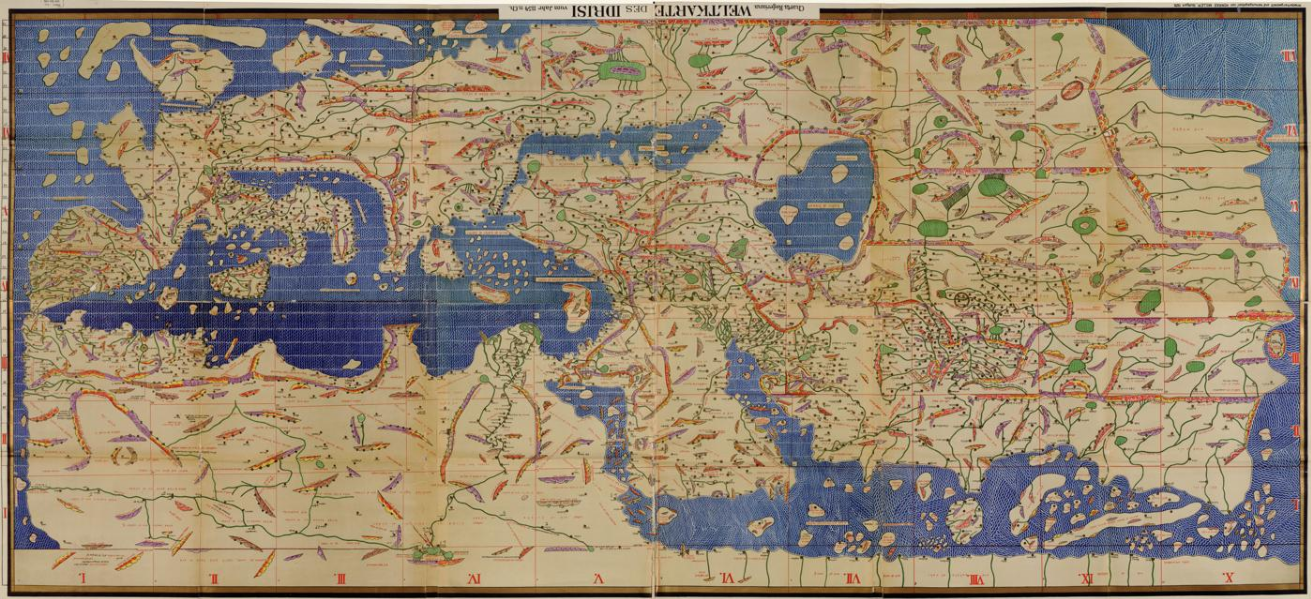

In astronomy, Muḥammad ibn Jābir al-Ḥarrānī al-Battānī improved the precision of the measurement of the precession of the Earth's axis. The corrections made to the geocentric model by al-Battani, Averroes, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Mu'ayyad al-Din al-'Urdi and Ibn al-Shatir were later incorporated into the Copernican heliocentric model. Heliocentric theories were also discussed by several other Muslim astronomers such as Al-Biruni, Al-Sijzi, Qotb al-Din Shirazi, and Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī. The astrolabe, though originally developed by the Greeks, was perfected by Islamic astronomers and engineers, and was subsequently brought to Europe.

Some most famous scientists from the medieval Islamic world include Jābir ibn Hayyān, al-Farabi, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi, Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Biruni, Avicenna, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, and Ibn Khaldun.

Technology

In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China.[57] The knowledge of gunpowder was also transmitted from China via predominantly Islamic countries,[58] where formulas for pure potassium nitrate[59][60] were developed.

Advances were made in irrigation and farming, using new technology such as the windmill. Crops such as almonds and citrus fruit were brought to Europe through al-Andalus, and sugar cultivation was gradually adopted by the Europeans. Arab merchants dominated trade in the Indian Ocean until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century. Hormuz was an important center for this trade. There was also a dense network of trade routes in the Mediterranean, along which Muslim-majority countries traded with each other and with European powers such as Venice, Genoa and Catalonia. The Silk Road crossing Central Asia passed through Islamic states between China and Europe. The emergence of major economic empires with technological resources after the conquests of Timur (Tamerlane) and the resurgence of the Timurid Renaissance include the Mali Empire and the India's Bengal Sultanate in particular, a major global trading nation in the world, described by the Europeans to be the "richest country to trade with".[61]

Muslim engineers in the Islamic world made a number of innovative industrial uses of hydropower, and early industrial uses of tidal power and wind power,[62] fossil fuels such as petroleum, and early large factory complexes (tiraz in Arabic).[63] The industrial uses of watermills in the Islamic world date back to the 7th century, while horizontal-wheeled and vertical-wheeled water mills were both in widespread use since at least the 9th century. A variety of industrial mills were being employed in the Islamic world, including early fulling mills, gristmills, paper mills, hullers, sawmills, ship mills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, tide mills and windmills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial mills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[57] Muslim engineers also invented crankshafts and water turbines, employed gears in mills and water-raising machines, and pioneered the use of dams as a source of water power, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[64] Such advances made it possible for industrial tasks that were previously driven by manual labour in ancient times to be mechanized and driven by machinery instead in the medieval Islamic world. The transfer of these technologies to medieval Europe had an influence on the Industrial Revolution, particularly from the proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal and Tipu Sultan's Kingdom, through the conquests of the East India Company.[65]

3. History

The history of the Islamic faith as a religion and social institution begins with its inception around 610 CE, when the Islamic prophet Muhammad, a native of Mecca, is believed by Muslims to have received the first revelation of the Quran, and began to preach his message.[66] In 622 CE, facing opposition in Mecca, he and his followers migrated to Yathrib (now Medina), where he was invited to establish a new constitution for the city under his leadership.[66] This migration, called the Hijra, marks the first year of the Islamic calendar. By the time of his death, Muhammad had become the political and spiritual leader of Medina, Mecca, the surrounding region, and numerous other tribes in the Arabian Peninsula.[66]

After Muhammad died in 632, his successors (the Caliphs) continued to lead the Muslim community based on his teachings and guidelines of the Quran. The majority of Muslims consider the first four successors to be 'rightly guided' or Rashidun. The conquests of the Rashidun Caliphate helped to spread Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula, stretching from northwest India, across Central Asia, the Near East, North Africa, southern Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees. The Arab Muslims were unable to conquer the entire Christian Byzantine Empire in Asia Minor during the Arab–Byzantine wars, however. The succeeding Umayyad Caliphate attempted two failed sieges of Constantinople in 674–678 and 717–718. Meanwhile, the Muslim community tore itself apart into the rivalling Sunni and Shia sects since the killing of caliph Uthman in 656, resulting in a succession crisis that has never been resolved.[67] The following First, Second and Third Fitnas and finally the Abbasid Revolution (746–750) also definitively destroyed the political unity of the Muslims, who have been inhabiting multiple states ever since.[68] Ghaznavids' rule was succeeded by the Ghurid Empire of Muhammad of Ghor and Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad, whose reigns under the leadership of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji extended until the Bengal, where Indian Islamic missionaries achieved their greatest success in terms of dawah and number of converts to Islam.[69][70] Qutb-ud-din Aybak conquered Delhi in 1206 and began the reign of the Delhi Sultanate,[71] a successive series of dynasties that synthesized Indian civilization with the wider commercial and cultural networks of Africa and Eurasia, greatly increased demographic and economic growth in India and deterred Mongol incursion into the prosperous Indo-Gangetic Plain and enthroned one of the few female Muslim rulers, Razia Sultana.[72] Notable major empires dominated by Muslims, such as those of the Abbasids, Fatimids, Almoravids, Seljukids, Ajuran, Adal and Warsangali in Somalia, Mughals in the Indian subcontinent (India, Bangladesh, Pakistan e.t.c), Safavids in Persia and Ottomans in Anatolia, were among the influential and distinguished powers in the world. 19th-century colonialism and 20th-century decolonisation have resulted in several independent Muslim-majority states around the world, with vastly differing attitudes towards and political influences granted to, or restricted for, Islam from country to country. These have revolved around the question of Islam's compatibility with other ideological concepts such as secularism, nationalism (especially Arab nationalism and Pan-Arabism, as opposed to Pan-Islamism), socialism (see also Arab socialism and socialism in Iran), democracy (see Islamic democracy), republicanism (see also Islamic republic), liberalism and progressivism, feminism, capitalism and more.

3.1. Mongol Invasions

-

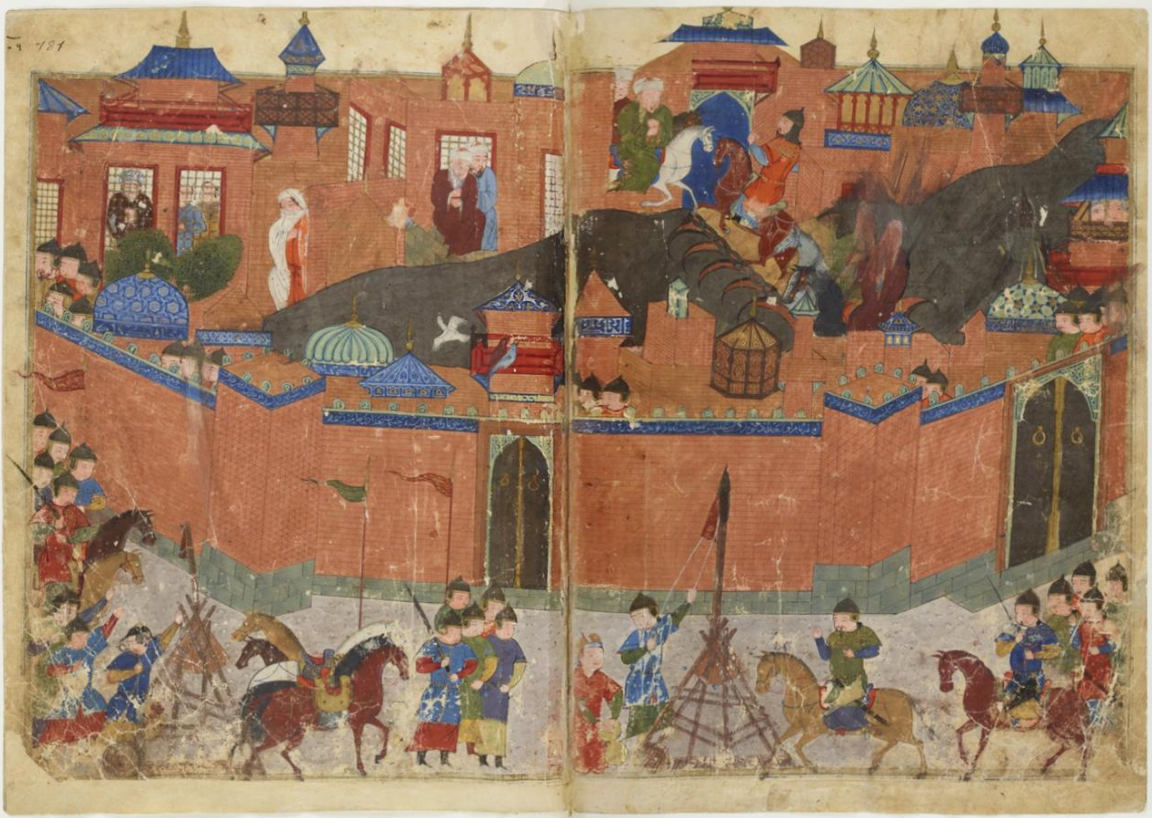

The city of Baghdad being besieged during the Mongolian invasions. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1831791

-

Mongol armies capture of the Alamut, Persian miniature. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1200692

3.2. Gunpowder Empires

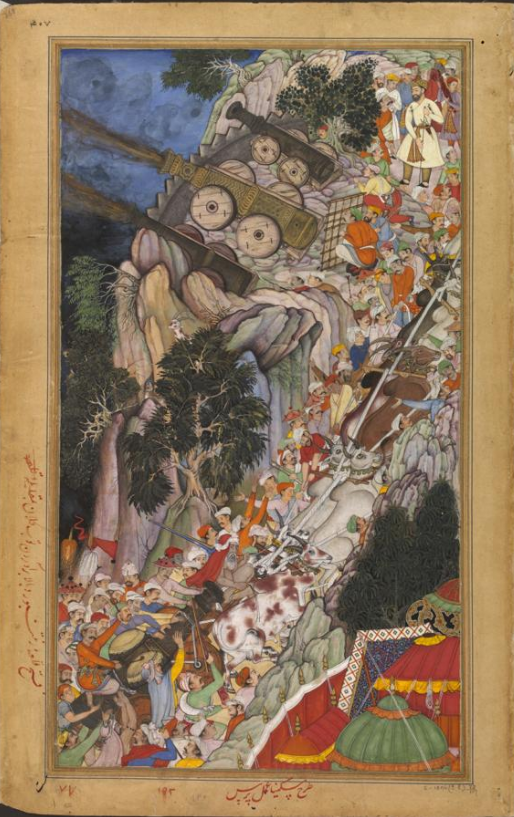

Scholars often use the term Age of the Islamic Gunpowders to describe period the Safavid, Ottoman and Mughal states. Each of these three empires had considerable military exploits using the newly developed firearms, especially cannon and small arms, to create their empires.[73] They existed primarily between the fourteenth and the late seventeenth centuries.[74] During the 17th–18th centuries, when the Indian subcontinent was ruled by Mughal Empire's sixth ruler Muhammad Auranzgeb through sharia and Islamic economics,[75][76] India became the world's largest economy, valued 25% of world GDP,[77] having better conditions to 18th-century Western Europe, prior to the Industrial Revolution,[78] causing the emergence of the period of proto-industrialization.[78]

-

Safavid Empire's Zamburak. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1607680

-

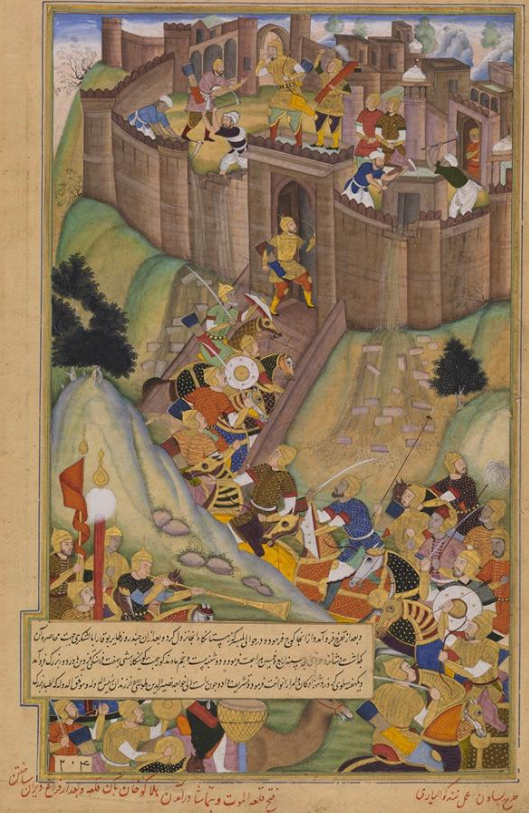

Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during Mughal Emperor Akbar's Siege of Ranthambore Fort in 1568.[79] https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1937389

-

The Mughal Army under the command of Islamist Aurangzeb recaptures Orchha in October 1635. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1961136

Gun-wielding Ottoman Janissaries in combat against the Knights of Saint John at the Siege of Rhodes in 1522. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1614343

-

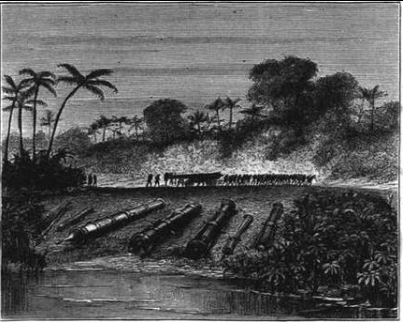

Cannons and guns belonging to the Aceh Sultanate (in modern Indonesia). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1117224

3.3. Great Divergence

Ibrahim Muteferrika, Rational basis for the Politics of Nations (1731)[80]

The Great Divergence was the reason why European colonial powers militarily defeated preexisting Oriental powers like the Mughal Empire, starting from the wealthy Bengal Subah, Tipu Sultan's Kingdom of Mysore, the Ottoman Empire and many smaller states in the pre-modern Greater Middle East, and initiated a period known as 'colonialism'.[80]

-

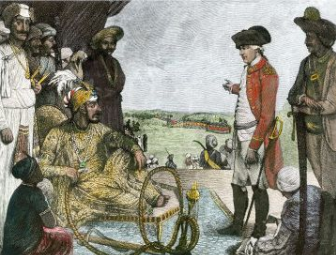

Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II negotiates with the East India Company after being defeated during the Battle of Buxar. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1237498

-

East India Company's Robert Clive meeting the Nawabs of Bengal before the Battle of Plassey. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1838191

-

Siege of Ochakov (1788), an armed conflict between the Ottomans and the Russian Tsardom. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1754960

-

Combat during the Russo-Persian Wars. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1517920

-

French campaign in Egypt and Syria against the Mamluks and Ottomans. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1761861

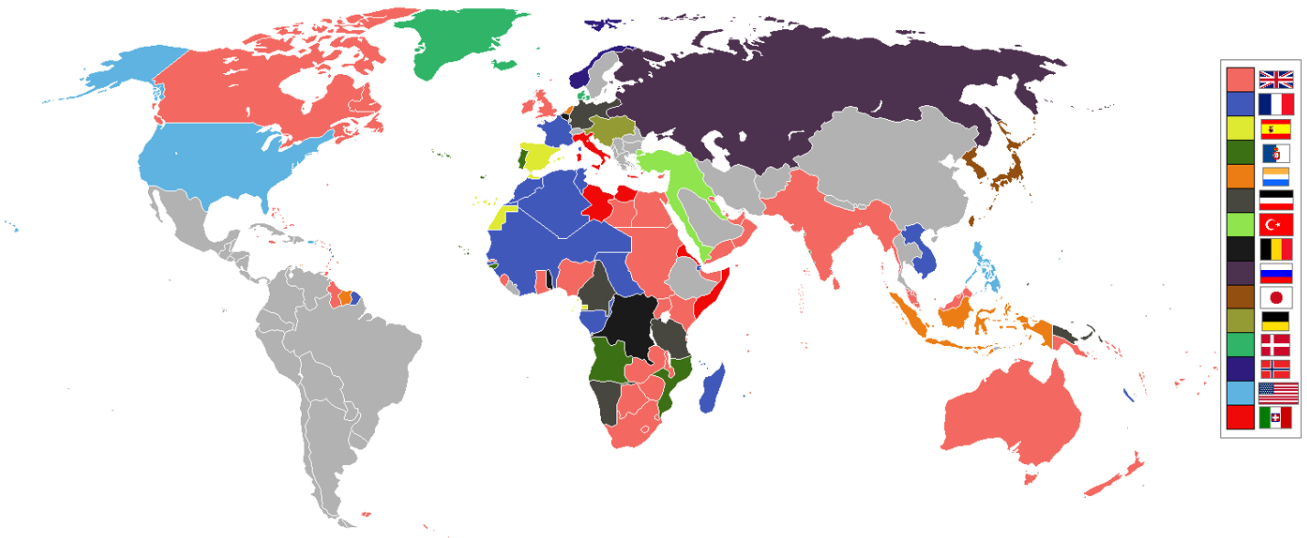

3.4. Colonialism

Beginning with the 15th century, colonialism by European powers profoundly affected Muslim-majority societies in Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Colonialism was often advanced by conflict with mercantile initiatives by colonial powers and caused tremendous social upheavals in Muslim-dominated societies.[81]

A number of Muslim-majority societies reacted to Western powers with zealotry and thus initiating the rise of Pan-Islamism; or affirmed more traditionalist and inclusive cultural ideals; and in rare cases adopted modernity that was ushered by the colonial powers.[81][82]

The only Muslim-majority regions not to be colonized by the Europeans were Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and Afghanistan. Turkey was one of the first colonial powers of the world with the Ottoman empire ruling several states for over 6 centuries.

-

The Java War between the Netherlands and Javanese aristocracy led by Prince Diponegoro, from 1825 to 1830. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1342203

-

The French conquest of Algeria, from 1830 to 1903. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1934389

-

The Hispano-Moroccan War between Spain and Morocco, from 1859 to 1860. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1362067

-

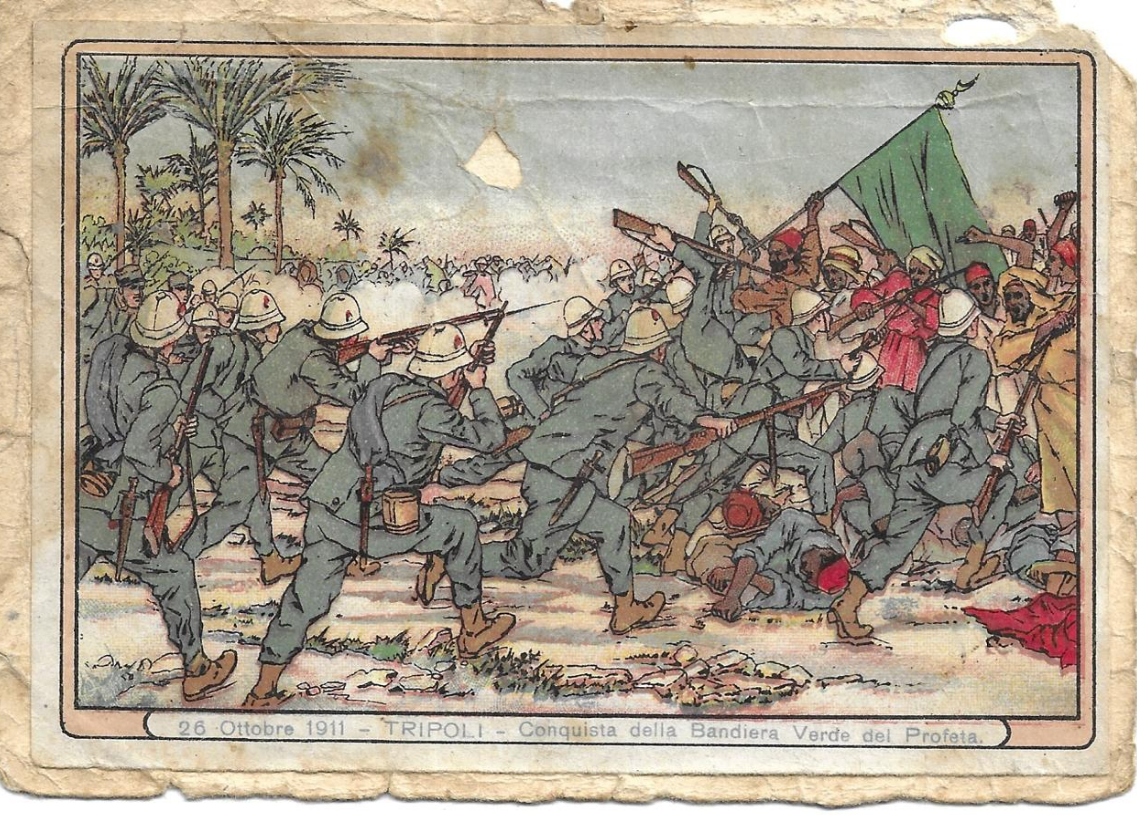

The Italo-Turkish War between Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 1911 to 1912. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1903302

-

The Christian reconquest of Buda, Ottoman Hungary, 1686, painted by Frans Geffels. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1799691

-

French conquest of Algeria (1830–1857). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1113060

-

Anglo-Egyptian invasion of Sudan 1896–1899. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1128155

-

The Melilla War between Spain and Rif Berbers of Morocco in 1909. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1558646

3.5. Postcolonial Era

In the 20th century, the end of the European colonial domination has led to creation of a number of nation states with significant Muslim populations. These states drew on Islamic traditions to varying degree and in various ways in organizing their legal, educational and economic systems.[81]

A significant change in the Muslim world was the defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922), to which the Ottoman officer and Turkish revolutionary statesman Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had an instrumental role in ending and replacing it with the Republic of Turkey, a modern, secular democracy[83] (see Abolition of the Ottoman sultanate).[83] The secular values of Kemalist Turkey, which separated religion from the state with the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924,[83] have sometimes been seen as the result of Western influence.

In the 21st century, after the September 11 attacks (2001) coordinated by the Wahhabi Islamist[84] terrorist group[85] Al-Qaeda[85][86][87][88] against the United States, scholars considered the ramifications of seeking to understand Muslim experience through the framework of secular Enlightenment principles. Muhammad Atta, one of the 11 September hijackers, reportedly quoted from the Quran to allay his fears: "Fight them, and God will chastise them at your hands/And degrade them, and He will help you/Against them, and bring healing to the breasts of a people who believe", referring to the ummah, the community of Muslim believers, and invoking the imagery of the early warriors of Islam who lead the faithful from the darkness of jahiliyyah.[89]

By Sayyid Qutb's definition of Islam, the faith is "a complete divorce from jahiliyyah". He complained that American churches served as centers of community social life that were "very hard [to] distinguish from places of fun and amusement". For Qutb, Western society was the modern jahliliyyah. His understanding of the "Muslim world" and its "social order" was that, presented to the Western world as the result of practicing Islamic teachings, would impress "by the beauty and charm of true Islamic ideology". He argued that the values of the Enlightenment and its related precursor, the Scientific Revolution, "denies or suspends God's sovereignty on earth" and argued that strengthening "Islamic character" was needed "to abolish the negative influences of jahili life."[89]

4. Geography

According to a 2010 study and released January 2011,[90][91] Islam had 1.5 billion adherents, making up c. 22% of the world population.[92][93][94] Because the terms 'Muslim world' and 'Islamic world' are disputed, since no country is homogeneously Muslim, and there is no way to determine at what point a Muslim minority in a country is to be considered 'significant' enough, there is no consensus on how to define the Muslim world geographically.[3][4][6] The only rule of thumb for inclusion which has some support, is that countries need to have a Muslim population of more than 50%.[3][6] According to the Pew Research Center in 2015 there were 50 Muslim-majority countries.[95][96] Jones (2005) defines a "large minority" as being between 30% and 50%, which described nine countries in 2000, namely Bosnia and Herzegovina, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, North Macedonia, and Tanzania.[6]

Islam is the second largest religion in numerous other countries, including: Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Georgia, Israel, India, Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines , Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Central African Republic, Gabon, Cameroon, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia and Guinea-Bissau.

5. Government

In its list of Islamic countries of the world, WorldAtlas identifies six major Islamic states, meaning countries that base their systems of government on Sharia law: Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Mauritania, and Yemen. Other countries not considered Islamic states, but which politically define Islam as the state religion, are listed as: Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Algeria, Malaysia, Maldives, Morocco, Libya, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, Somalia, and Brunei. It is noted that Libya also has 18 other official state religions. Neutral Muslim majority countries, in which Islam is not the state religion, are: Niger, Indonesia, Sudan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sierra Leone, and Djibouti. Countries with a majority of Muslims, that have declared an official separation of religion and state, are listed as secular Muslim majority countries: Albania, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Chad, The Gambia, Guinea, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Northern Cyprus, Nigeria, Senegal, Syria, Lebanon, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.[97]

5.1. Religion and State

As the Muslim world came into contact with secular ideals, societies responded in different ways. Some Muslim-majority countries are secular. Azerbaijan became the first secular republic in the Muslim world, between 1918 and 1920, before it was incorporated into the Soviet Union.[98][99][100] Turkey has been governed as a secular state since the reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[101] By contrast, the 1979 Iranian Revolution replaced a monarchial semi-secular regime with an Islamic republic led by the Ayatollah, Ruhollah Khomeini.[102][103]

Some countries have declared Islam as the official state religion. In those countries, the legal code is largely secular. Only personal status matters pertaining to inheritance and marriage are governed by Sharia law.[104]

Islamic states

Islamic states have adopted Islam as the ideological foundation of state and constitution.

Afghanistan[97][105]

Afghanistan[97][105] Iran[97][106]

Iran[97][106] Mauritania[97][107]

Mauritania[97][107] Pakistan[97][108]

Pakistan[97][108] Saudi Arabia[97][109]

Saudi Arabia[97][109] Yemen[97][110]

Yemen[97][110]

State religion

The following Muslim-majority nation-states have endorsed Islam as their state religion, and though they may guarantee freedom of religion for citizens, do not declare a separation of state and religion:

Algeria[97][111]

Algeria[97][111] Bangladesh[97][112]

Bangladesh[97][112] Brunei[97][113]

Brunei[97][113] Comoros[114]

Comoros[114] Egypt[97][115]

Egypt[97][115] Iraq[97][116]

Iraq[97][116] Jordan[97][117]

Jordan[97][117] Kuwait[97][118]

Kuwait[97][118] Libya[97][119]

Libya[97][119] Malaysia[97][120]

Malaysia[97][120] Maldives[97][121]

Maldives[97][121] Morocco[97][122]

Morocco[97][122] Palestine[123]

Palestine[123] Somalia[97][124]

Somalia[97][124] Tunisia[97][125]

Tunisia[97][125] United Arab Emirates[97][126]

United Arab Emirates[97][126]

Secular states

Secular states in the Muslim world have declared separation between civil/government affairs and religion.

Albania[97][127]

Albania[97][127] Azerbaijan[97][128]

Azerbaijan[97][128] Bosnia and Herzegovina[129]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[129] Burkina Faso[97][130]

Burkina Faso[97][130] Chad[97][131]

Chad[97][131] The Gambia[97][132]

The Gambia[97][132] Guinea[97][133]

Guinea[97][133] Guinea-Bissau[134]

Guinea-Bissau[134] Indonesia[135]

Indonesia[135] Kazakhstan[97][136]

Kazakhstan[97][136] Kosovo[97][137]

Kosovo[97][137] Kyrgyzstan[97][138]

Kyrgyzstan[97][138] Lebanon[97]

Lebanon[97] Mali[97][139]

Mali[97][139] Niger[140]

Niger[140] Nigeria[97][141]

Nigeria[97][141] Senegal[97][142]

Senegal[97][142] Sierra Leone[143]

Sierra Leone[143] Sudan[144]

Sudan[144] Syria[145]

Syria[145] Tajikistan[97][146]

Tajikistan[97][146] Turkey[97][147]

Turkey[97][147] Turkmenistan[97][148]

Turkmenistan[97][148] Uzbekistan[97][149]

Uzbekistan[97][149]

5.2. Law and Ethics

In some states, Muslim ethnic groups enjoy considerable autonomy.

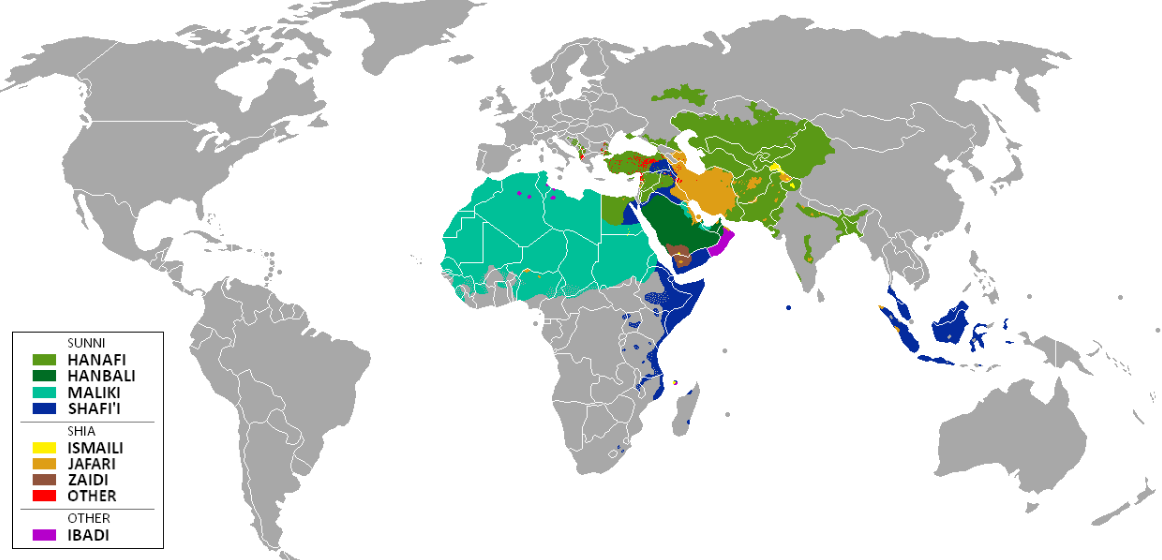

In some places, Muslims implement Islamic law, called sharia in Arabic. The Islamic law exists in a number of variations, called schools of jurisprudence. The Amman Message, which was endorsed in 2005 by prominent Islamic scholars around the world, recognized four Sunni schools (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali), two Shia schools (Ja'fari, Zaidi), the Ibadi school, and the Zahiri school.[150]

- Hanafi school in Pakistan, North India, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Turkey, Albania, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, other Balkan States, Lower Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Russia, Caucasus Republics, China, and Central Asian Republics.

- Maliki in North Africa, West Africa, Sahel, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait.

- Shafi'i in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Eritrea, Somalia, Yemen, Maldives, Sri Lanka, and South India

- Hanbali in Saudi Arabia,

- Jaferi in Iran, Iraq, Bahrain and Azerbaijan. These four are the only "Muslim states" where the majority is Shia population. In Yemen, Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Turkey, and Syria, are countries with Sunni populations. In Lebanon, the majority Muslims (54%) were about equally divided between Sunni and Shia in 2010.

- Ibadi in Oman and small regions in North Africa.

In a number of Muslim-majority countries the law requires women to cover either their legs, shoulders and head, or the whole body apart from the face. In strictest forms, the face as well must be covered leaving just a mesh to see through. These hijab rules for dressing cause tensions, concerning particularly Muslims living in Western countries, where restrictions are considered both sexist and oppressive. Some Muslims oppose this charge, and instead declare that the media in these countries presses on women to reveal too much to be deemed attractive, and that this is itself sexist and oppressive.

5.3. Politics

During much of the 20th century, the Islamic identity and the dominance of Islam on political issues have arguably increased during the early 21st century. The fast-growing interests of the Western world in Islamic regions, international conflicts and globalization have changed the influence of Islam on the world in contemporary history.[152]

Islamism

6. Demographics

More than 24.1% of the world's population is Muslim.[153][154] Current estimates conclude that the number of Muslims in the world is around 1.8 billion.[153] Muslims are the majority in 49 countries,[155] they speak hundreds of languages and come from diverse ethnic backgrounds. The city of Karachi has the largest Muslim population in the world.[156][157]

6.1. Religion

The two main denominations of Islam are the Sunni and Shia sects. They differ primarily upon of how the life of the ummah ("faithful") should be governed, and the role of the imam. Sunnis believe that the true political successor of Muhammad according to the Sunnah should be selected based on ٍShura (consultation), as was done at the Saqifah which selected Abu Bakr, Muhammad's father-in-law, to be Muhammad's political but not his religious successor. Shia, on the other hand, believe that Muhammad designated his son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib as his true political as well as religious successor.[158]

The overwhelming majority of Muslims in the world, between 87 and 90%, are Sunni.[159]

Shias and other groups make up the rest, about 10–13% of overall Muslim population. The countries with the highest concentration of Shia populations are: Iran – 89%,[160] Azerbaijan – 85%,[161] Iraq – 60/70%,[162] Bahrain – 70%, Yemen – 47%,[163] Turkey – 28%,[164][165] Lebanon – 27%, Syria – 17%, Afghanistan – 15%, Pakistan – 5%/10%,[166][167][168][169][170][171][172][173][174] and India – 5%.[175]

The Kharijite Muslims, who are less known, have their own stronghold in the country of Oman holding about 75% of the population.[176]

-

Turkish Muslims at the Eyüp Sultan Mosque on Eid al-Adha. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1159811

-

Shi'a Muslims in Iran commemorate Ashura. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1563407

-

Friday prayer for Sunni Muslims in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1289048

Islamic schools and branches

The first centuries of Islam gave rise to three major sects: Sunnis, Shi'as and Kharijites. Each sect developed distinct jurisprudence schools (madhhab) reflecting different methodologies of jurisprudence (fiqh).

The major Sunni madhhabs are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali.[177]

The major Shi'a branches are Twelver (Imami), Ismaili (Sevener) and Zaidi (Fiver). Isma'ilism later split into Nizari Ismaili and Musta’li Ismaili, and then Mustaali was divided into Hafizi and Taiyabi Ismailis.[178] It also gave rise to the Qarmatian movement and the Druze faith. Twelver Shiism developed Ja'fari jurisprudence whose branches are Akhbarism and Usulism, and other movements such as Alawites, Shaykism[179] and Alevism.[180][181]

Similarly, Kharijites were initially divided into five major branches: Sufris, Azariqa, Najdat, Adjarites and Ibadis.

Among these numerous branches, only Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali, Imamiyyah-Ja'fari-Usuli, Nizārī Ismā'īlī, Alevi,[182] Zaydi, Ibadi, Zahiri, Alawite,[183] Druze and Taiyabi communities have survived. In addition, new schools of thought and movements like Quranist Muslims and Ahmadi Muslims later emerged independently.

-

A Sufi dervish drums up the Friday afternoon crowd in Omdurman, Sudan. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1731539

-

Druze dignitaries celebrating the Nabi Shu'ayb festival at the tomb of Muhammad in Hittin. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1465775

-

Ibadis living in the M'zab valley in Algerian Sahara. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1542892

-

Zaydi Imams ruled in Yemen until 1962. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1098755

-

Most of the inhabitants of the Hunza Valley in Pakistan are Ismaili Muslims. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1907597

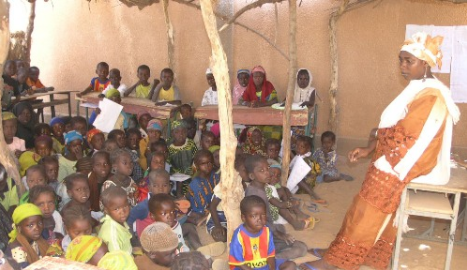

6.2. Literacy and Education

The literacy rate in the Muslim world varies. Azerbaijan is in second place in the Index of Literacy of World Countries. Some members such as Iran, Kuwait, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan have over 97% literacy rates, whereas literacy rates are the lowest in Mali, Afghanistan, Chad and parts of Africa. Several Muslim-majority countries, such as Turkey, Iran and Egypt have a high rate of citable scientific publications.[184][185]

In 2015, the International Islamic News Agency reported that nearly 37% of the population of the Muslim world is unable to read or write, basing that figure on reports from the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.[186] In Egypt, the largest Muslim-majority Arab country, the youth female literacy rate exceeds that for males.[187] Lower literacy rates are more prevalent in South Asian countries such as in Afghanistan and Pakistan, but are rapidly increasing.[188] In the Eastern Middle East, Iran has a high level of youth literacy at 98%,[189] whereas Iraq's youth literacy rate has sharply declined from 85% to 57%, during the American-led war and subsequent occupation.[190] Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country in the world, has a 99% youth literacy rate.[191]

A 2011 Pew Research Center showed that at the time about 36% of all Muslims had no formal schooling, with only 8% having graduate and post-graduate degrees.[192] The highest of years of schooling among Muslim-majority countries found in Uzbekistan (11.5), Kuwait (11.0) and Kazakhstan (10.7).[192] In addition, the average of years of schooling in countries where Muslims are the majority is 6.0 years of schooling, which lag behind the global average (7.7 years of schooling).[192] In the youngest age (25–34) group surveyed, Young Muslims have the lowest average levels of education of any major religious group, with an average of 6.7 years of schooling, which lag behind the global average (8.6 years of schooling).[192] The study found that Muslims have a significant amount of gender inequality in educational attainment, since Muslim women have an average of 4.9 years of schooling, compared to an average of 6.4 years of schooling among Muslim men.[192]

-

Young school girls in Paktia Province of Afghanistan. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1720307

- Schoolgirls in Gaza lining up for class, 2009. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1173141

-

Medical students of anatomy, before an exam in moulage, Iran. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1445682

6.3. Refugees

According to the UNHCR, Muslim-majority countries hosted 18 million refugees by the end of 2010.

Since then Muslim-majority countries have absorbed refugees from recent conflicts, including the uprising in Syria.[193] In July 2013, the UN stated that the number of Syrian refugees had exceeded 1.8 million.[194] In Asia, an estimated 625,000 refugees from Rakhine, Myanmar, mostly Muslim, had crossed the border into Bangladesh since August 2017.[195]

7. Culture

Throughout history, Muslim cultures have been diverse ethnically, linguistically and regionally. According to M.M. Knight, this diversity includes diversity in beliefs, interpretations and practices and communities and interests. Knight says perception of Muslim world among non-Muslims is usually supported through introductory literature about Islam, mostly present a version as per scriptural view which would include some prescriptive literature and abstracts of history as per authors own point of views, to which even many Muslims might agree, but that necessarily would not reflect Islam as lived on the ground, 'in the experience of real human bodies'.[196]

7.1. Arts

The term "Islamic art and architecture" denotes the works of art and architecture produced from the 7th century onwards by people who lived within the territory that was inhabited by culturally Islamic populations.[197][198]

Architecture

Aniconism

No Islamic visual images or depictions of God are meant to exist because it is believed that such artistic depictions may lead to idolatry. Moreover, Muslims believe that God is incorporeal, making any two- or three- dimensional depictions impossible. Instead, Muslims describe God by the names and attributes that, according to Islam, he revealed to his creation. All but one sura of the Quran begins with the phrase "In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful". Images of Mohammed are likewise prohibited. Such aniconism and iconoclasm[199] can also be found in Jewish and some Christian theology.

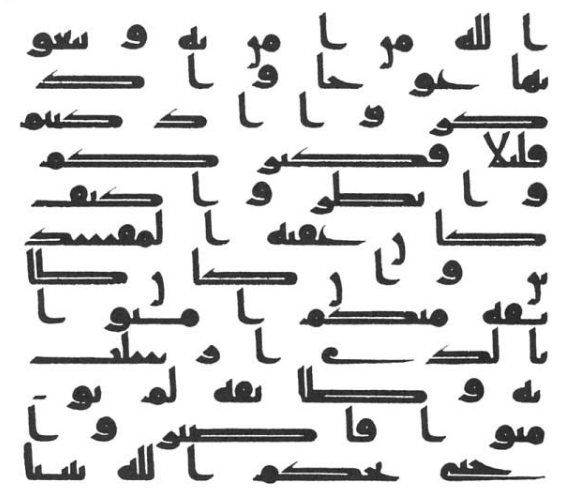

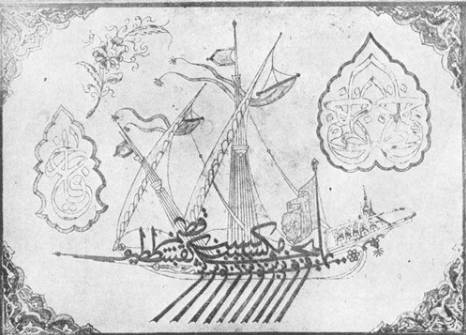

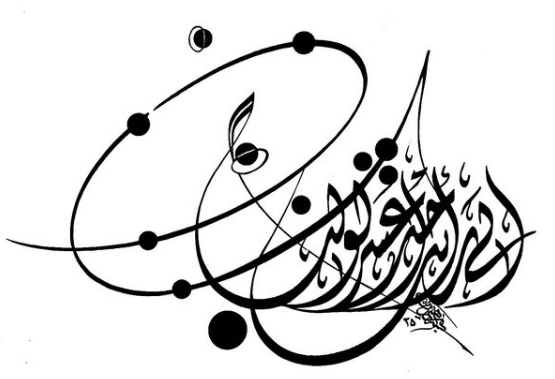

Arabesque

Islamic art frequently adopts the use of geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as arabesque. Such designs are highly nonrepresentational, as Islam forbids representational depictions as found in pre-Islamic pagan religions. Despite this, there is a presence of depictional art in some Muslim societies, notably the miniature style made famous in Persia and under the Ottoman Empire which featured paintings of people and animals, and also depictions of Quranic stories and Islamic traditional narratives. Another reason why Islamic art is usually abstract is to symbolize the transcendence, indivisible and infinite nature of God, an objective achieved by arabesque.[200] Islamic calligraphy is an omnipresent decoration in Islamic art, and is usually expressed in the form of Quranic verses. Two of the main scripts involved are the symbolic kufic and naskh scripts, which can be found adorning the walls and domes of mosques, the sides of minbars, and so on.[200]

Distinguishing motifs of Islamic architecture have always been ordered repetition, radiating structures, and rhythmic, metric patterns. In this respect, fractal geometry has been a key utility, especially for mosques and palaces. Other features employed as motifs include columns, piers and arches, organized and interwoven with alternating sequences of niches and colonnettes.[201] The role of domes in Islamic architecture has been considerable. Its usage spans centuries, first appearing in 691 with the construction of the Dome of the Rock mosque, and recurring even up until the 17th century with the Taj Mahal. And as late as the 19th century, Islamic domes had been incorporated into European architecture.[202]

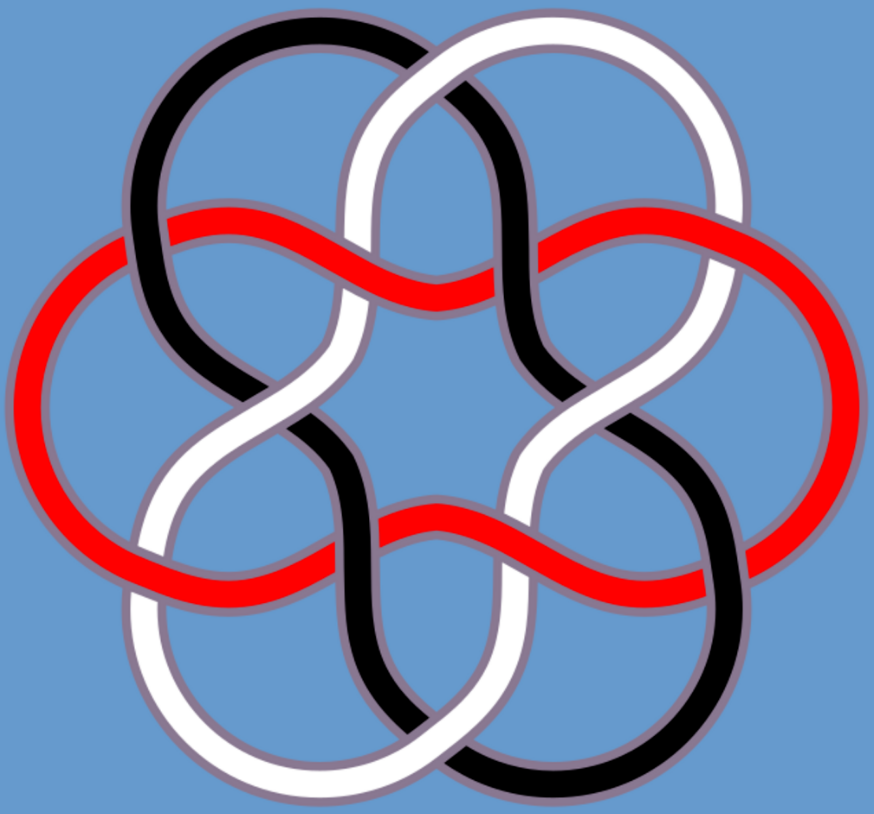

-

Example of an Arabesque. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2071671

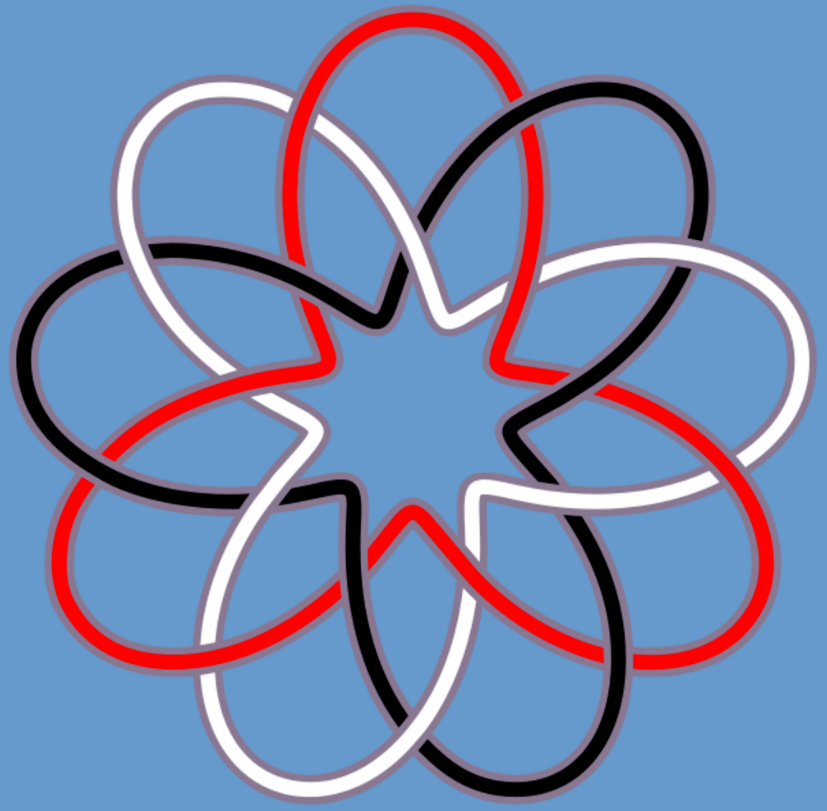

-

Example of an Arabesque. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1999627

-

Example of an Arabesque. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2055745

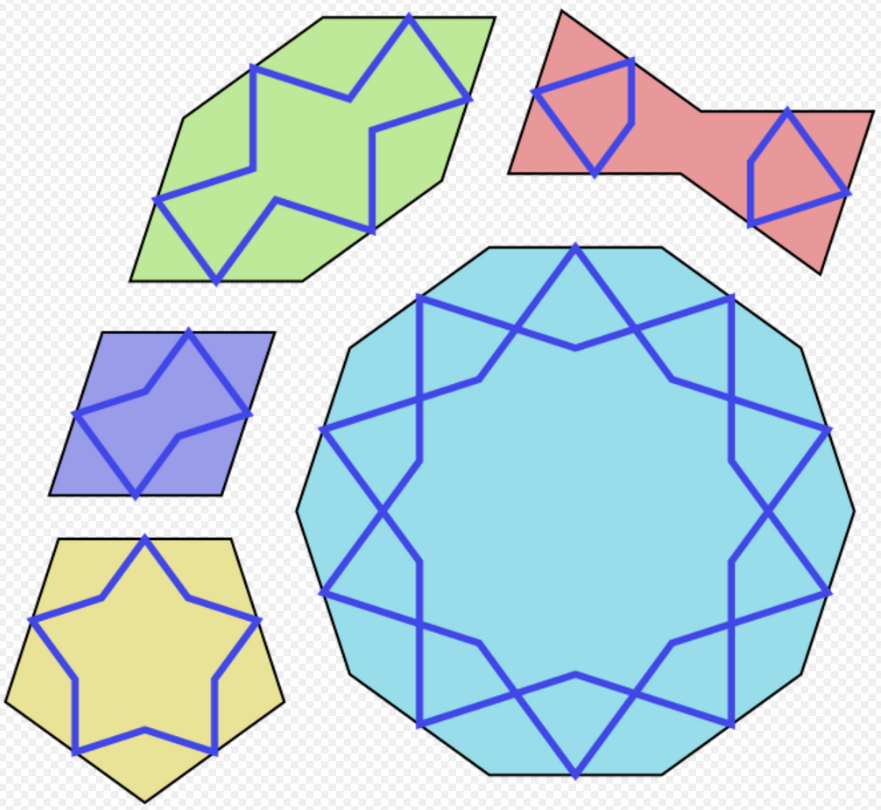

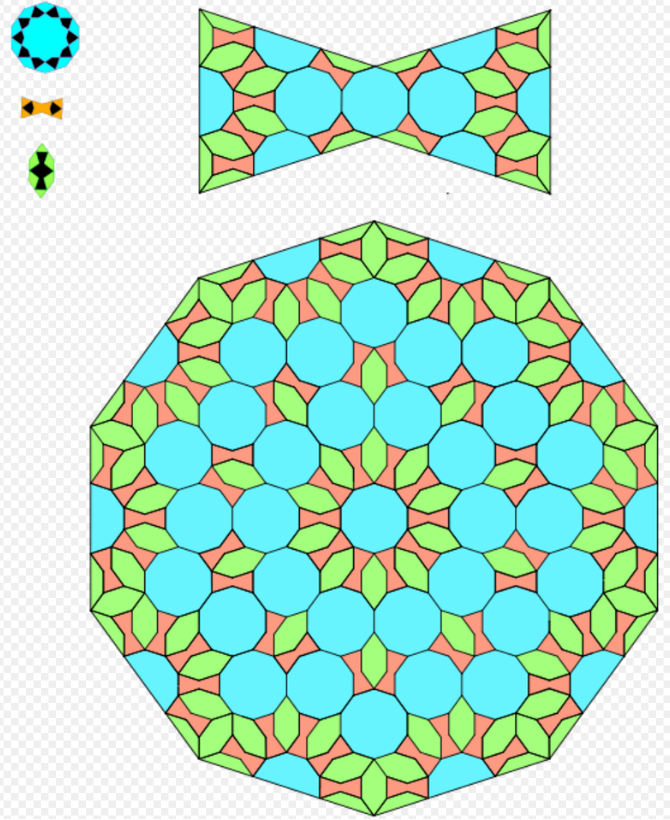

Girih

-

Girih tiles. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1077374

-

The subdivision rule used to generate the Girih pattern on the spandrel. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2084664

-

Girih pattern that can be drawn with compass and straight edge. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2008617

Islamic calligraphy

-

Kufic script from an early Qur'an manuscript, 7th century. (Surah 7: 86–87). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1216356

-

Bismallah calligraphy. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2017176

-

Islamic calligraphy represented for amulet of sailors in the Ottoman Empire. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1242769

-

Islamic calligraphy praising Ali. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2053973

-

Modern Islamic calligraphy representing various planets. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1606300

7.2. Calendar

Two calendars are used all over the Muslim world. One is a lunar calendar that is most widely used among Muslims. The other one is a solar calendar officially used in Iran and Afghanistan.

Islamic lunar calendar

Solar Hijri calendar

8. Women

According to Riada Asimovic Akyol while Muslim women's experiences differs a lot by location and personal situations such as family upbringing, class and education;[203] the difference between culture and religions is often ignored by community and state leaders in many of the Muslim majority countries,[203] the key issue in the Muslim world regarding gender issues is that medieval religious texts constructed in highly patriarchal environments and based on biological essentialism are still valued highly in Islam; hence views emphasizing on men's superiority in unequal gender roles– are widespread among many conservative Muslims (men and women) .[203] Orthodox Muslims often believe that rights and responsibilities of women in Islam are different than that of men and sacrosanct since assigned by the God.[203] According to Asma Barlas patriarchal behaviour among Muslims is based in an ideology which jumbles sexual and biological differences with gender dualisms and inequality. Modernist discourse of liberal progressive movements like Islamic feminism have been revisiting hermeneutics of feminism in Islam in terms of respect for Muslim women's lives and rights.[203] Riada Asimovic Akyol further says that equality for Muslim women needs to be achieved through self-criticism.[203]

-

A Kazakh wedding ceremony in a mosque. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1872188

-

A group of marabouts – West African religious leaders and teachers of the Quran. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1978117

-

Muslim girls at Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1605152

-

A tribal delegation in Chad. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1584359

-

Minangkabau people (Padang, Western Sumatra) reciting Al-Qur'an. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1348149

-

Muslim girls walking for school in Bangladesh. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1991578

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Muslim_world

References

- Scott Carpenter, Soner Cagaptay (2 June 2009). "What Muslim World?". Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/06/02/what-muslim-world/.

- Afsaruddin, Asma (2016). "Islamic World". in McNeill, William H.. Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History. 1 (2nd ed.). Berkshire Publishing Group. doi:10.1093/acref/9780190622718.001.0001. ISBN 9781933782652. "The Islamic world is generally defined contemporaneously as consisting of nation-states whose population contains a majority of Muslims. [...] in the contemporary era, the term Islamic world now includes not only the traditional heartlands of Islam, but also Europe and North America, both of which have sizeable minority Muslim populations". https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Facref%2F9780190622718.001.0001

- Nawaz, Maajid (2012). Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism. WH Allen. p. XXII–XIII. ISBN 9781448131617. https://books.google.com/books?id=FIjms8hwoW8C. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2007). "Hitchens '07: Danish Muhammad Cartoons". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZZ96SArpuc. "21 ambassadors from Muslim – so-called "Muslim states". How do they dare to call themselves "Muslim"? In what sense is Egypt a "Muslim" country? You can't denominate a country as religious." (4:35)

- Gert Jan Geling (12 January 2017). "Ook na 1400 jaar kan de islam heus verdwijnen" (in nl). Trouw. https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/ook-na-1400-jaar-kan-de-islam-heus-verdwijnen~bc232725/. ""Many people, including myself, are often guilty of using terms such as 'Muslim countries', or the 'Islamic world', as if Islam has always been there, and always will be. And that is completely unclear. (...) If the current trend [of apostasy] continues, at some point a large section of the population may no longer be religious. How 'Islamic' would that still make the 'Islamic world'?"

- Jones, Gavin W. (2005). Islam, the State and Population. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 11–14. ISBN 9781850654933. https://books.google.com/books?id=6v38-ZDJYUMC&pg=PA11. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- George Saliba (1994), A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam, pp. 245, 250, 256–7. New York University Press, ISBN:0-8147-8023-7.

- King, David A. (1983). "The Astronomy of the Mamluks". Isis 74 (4): 531–555. doi:10.1086/353360. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/f6d729951791821ed435a9819edbc6726650c3fe. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Medieval India, NCERT, ISBN:81-7450-395-1

- Vartan Gregorian, "Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith", Brookings Institution Press, 2003, pg 26–38 ISBN:0-8157-3283-X

- Islamic Radicalism and Multicultural Politics. Taylor & Francis. 1 March 2011. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-136-95960-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=JdC90uc8PfQC&pg=PA9. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Saliba, George (July 1995). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. ISBN 9780814780237. https://books.google.com/books?id=mOquCzBX3xcC&q=golden+age+of+islam+university&pg=PR7. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Vartan Gregorian, "Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith", Brookings Institution Press, 2003, pp. 26–38 ISBN:0-8157-3283-X

- Mason, Robert (1995)."New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World". Muqarnas V 12 p.1

- Mason, Robert (1995)."New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World". Muqarnas V 12 p. 5

- Mason, Robert (1995)."New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World". Muqarnas V 12 p. 7

- The Thousand and One Nights; Or, The Arabian Night's Entertainments - David Claypoole Johnston - Google Books . Books.google.com.pk. Retrieved on 23 September 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=ATkQAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA543&dq=princess+parizade#v=onepage&q=princess%20parizade&f=false

- Marzolph (2007). "Arabian Nights". Encyclopaedia of Islam. I. Leiden: Brill.

- Grant & Clute, p. 51

- L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p. 10 ISBN:0-87054-076-9

- Grant & Clute, p 52

- Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher , Encyclopedia of Islamic World). http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drroubi.html

- Nahyan A. G. Fancy (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288) ", pp. 95–101, Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame. http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615

- Muhammad b. Abd al-Malik Ibn Tufayl. Philosophus autodidactus, sive Epistola Abi Jaafar ebn Tophail de Hai ebn Yokdhan : in qua ostenditur, quomodo ex inferiorum contemplatione ad superiorum notitiam ratio humana ascendere possit. E Theatro Sheldoniano, excudebat Joannes Owens, 1700. https://books.google.com/books?id=yFAR_G7HM3QC

- Ala-al-din abu Al-Hassan Ali ibn Abi-Hazm al-Qarshi al-Dimashqi. The Theologus autodidactus of Ibn al-Nafīs. Clarendon P., 1968

- Claeys, Gregory (5 August 2010). The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139828420. https://books.google.com/books?id=sFCuoqykV9QC&q=ibn+al+nafis+first+science+fiction+novel&pg=PA236.

- Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher , Encyclopedia of Islamic World). http://www.islamset.com/isc/nafis/drroubi.html

- Nawal Muhammad Hassan (1980), Hayy bin Yaqzan and Robinson Crusoe: A study of an early Arabic impact on English literature, Al-Rashid House for Publication.

- Cyril Glasse (2001), New Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 202, Rowman Altamira, ISBN:0-7591-0190-6.

- Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", Journal of Religion and Health 43 (4): 357–77 [369].

- Martin Wainwright, Desert island scripts , The Guardian , 22 March 2003. http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,918454,00.html

- G. J. Toomer (1996), Eastern Wisedome and Learning: The Study of Arabic in Seventeenth-Century England, p. 222, Oxford University Press, ISBN:0-19-820291-1.

- The Inferno. Dante Alighieri. Bickers and Son, 1874.

- See Inferno (Dante); Eighth Circle (Fraud)

- Miguel Asín Palacios, Julián Ribera, Real Academia Española. La Escatologia Musulmana en la Divina Comedia. E. Maestre, 1819.

- See also: Miguel Asín Palacios.

- I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet, Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection Lettres Gothiques, Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37.

- Tr. The Book of Muhammad's Ladder

- Transliterated as Maometto.

- The Review : May–Dec. 1919, Volume 1. The National Weekly Corp., 1919. p. 128. https://books.google.com/books?id=YY5NAAAAYAAJ

- Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor, Sam Wanamaker Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare's Globe (cf. Mayor of London (2006), Muslims in London , pp. 14–15, Greater London Authority) http://www.london.gov.uk/gla/publications/equalities/muslims-in-london.pdf

- "Islamic Philosophy" , Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1998) http://www.rep.routledge.com/article/H057

- Majid Fakhry (2001). Averroes: His Life, Works and Influence. Oneworld Publications. ISBN:1-85168-269-4.

- Irwin, Jones (Autumn 2002). "Averroes' Reason: A Medieval Tale of Christianity and Islam". The Philosopher LXXXX (2).

- Russell (1994), pp. 224–62,

- Dominique Urvoy, "The Rationality of Everyday Life: The Andalusian Tradition? (Aropos of Hayy's First Experiences)", in Lawrence I. Conrad (1996), The World of Ibn Tufayl: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Ḥayy Ibn Yaqẓān, pp. 38–46, Brill Publishers, ISBN:90-04-09300-1.

- Muhammad ibn Abd al-Malik Ibn Tufail and Léon Gauthier (1981), Risalat Hayy ibn Yaqzan, p. 5, Editions de la Méditerranée.

- Russell (1994), pp. 224–39

- Russell (1994) p. 227

- Russell (1994), p. 247

- Kamal, Muhammad (2006). Mulla Sadra's Transcendent Philosophy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. pp. 9, 39. ISBN 978-0-7546-5271-7. OCLC 224496901. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/224496901

- Dr. S.R.W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture 12 (3).

- Al-Khalili, Jim (4 January 2009). "BBC News". http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7810846.stm.

- Plofker, Kim (2009), Mathematics in India: 500 BCE–1800 CE, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN:0-691-12067-6.

- Peter J. Lu, Harvard's Office of News and Public Affairs http://www.news.harvard.edu/gazette/2007/03.01/99-tiles.html

- Turner, H. (1997) pp. 136–38

- Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture 46 (1), pp. 1–30 [10].

- Arming the Periphery. Emrys Chew, 2012. p. 1823.

- Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources , History of Science and Technology in Islam. http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%202.htm

- Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries , History of Science and Technology in Islam. http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%203.htm

- Nanda, J. N (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. 2005. ISBN:978-81-8069-149-2. Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- Ahmad Y. al-Hassan (1976). Taqi al-Din and Arabic Mechanical Engineering, pp. 34–35. Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo.

- Maya Shatzmiller, p. 36.

- Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%2071.htm

- Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture 46 (1), pp. 1–30.

- Watt, William Montgomery (2003). Islam and the Integration of Society. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-17587-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=AQUZ6BGyohQC. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "islam. §7. Sektevorming". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Omajjaden §1. De Spaanse tak". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp. 227–228

- Majumdar, Dr. R.C., History of Mediaeval Bengal, First published 1973, Reprint 2006, Tulshi Prakashani, Kolkata, ISBN:81-89118-06-4

- Srivastava, Ashirvadi Lal (1929). The Sultanate Of Delhi 711–1526 AD. Shiva Lal Agarwala & Company. https://archive.org/stream/sultanateofdelhi001929mbp#page/n5/mode/2up.

- "Delhi Sultanate" (in en), Wikipedia, 3 July 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Delhi_Sultanate&oldid=904615508, retrieved 7 July 2019

- Evans, Charles T. "The Gunpowder Empires". Northern Virginia Community College. http://novaonline.nvcc.edu/eli/evans/his112/Notes/Gunpowder.html.

- "The Islamic Gunpowder Empires, 1300–1650". Pearson Education. http://wps.ablongman.com/long_brummett_cpp_11/35/9191/2353138.cw/index.html.

- Islamic and European Expansion: The Forging of a Global Order, Michael Adas, Temple University Press (Philadelphia, PA), 1993.

- Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2014) (in en). Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781783475728.

- Maddison, Angus (2003): Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics, OECD Publishing, ISBN:9264104143, pages 259–261 https://books.google.com/books?id=rHJGz3HiJbcC&pg=PA259

- van Voss, Lex Heerma; Hiemstra-Kuperus, Els; Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk (2010). "The Long Globalization and Textile Producers in India". The Ashgate Companion to the History of Textile Workers, 1650–2000. Ashgate Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 9780754664284. https://books.google.com/books?id=f95ljbhfjxIC&pg=PA255. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Unknown (1590–95). "Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during Akbar's attack on Ranthambhor Fort". http://warfare2.likamva.in/Moghul/Akbar/1568-Bullocks_dragging_siege-guns_up_hill_during_the_attack_on_Ranthambhor_Fort.htm.

- "The 6 killer apps of prosperity". http://www.ted.com/talks/niall_ferguson_the_6_killer_apps_of_prosperity.html.

- "Islamic world". Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Islamic-world/Islamic-history-from-1683-to-the-present-reform-dependency-and-recovery. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Levy, Jacob T., ed (2011). Colonialism and Its Legacies. (Contributors: Alfred T, Chakabarty D, Dussel E, Eze E, Hsueh V, Kohn M, Bhanu Mehta P, Muthu S, Parekh B, Pitts J, Schutte O, Souza J, Young IM). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Group. ISBN 9780739142943.

- Cuthell Jr., David Cameron (2009). "Archived copy". in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York City: Facts On File. pp. 56–60. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=QjzYdCxumFcC&pg=PA56. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. London and New York City: I.B. Tauris. p. 172.

- "Transnational Islamist Terrorism: Al Qaeda". Islamist Terrorism and Democracy in the Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2012. pp. 40–65. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511977367.003. ISBN 9780511977367. https://books.google.com/books?id=PlTKrMFyawoC&pg=PA40. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York City: Knopf. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-375-41486-2. https://archive.org/details/loomingtoweralqa00wrig.

- Moghadam, Assaf (2008). The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8018-9055-0.

- Livesey, Bruce (25 January 2005). "Special Reports – The Salafist Movement: Al Qaeda's New Front". WGBH educational foundation. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/front/special/sala.html. Geltzer, Joshua A. (2011). US Counter-Terrorism Strategy and al-Qaeda: Signalling and the Terrorist World-View (Reprint ed.). London and New York City: Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-0415664523.

- Owen, John M.; Owen, J. Judd (2010). Religion, the Enlightenment, and the New Global Order. p. 12. ISBN 9780231526623. https://books.google.com/books?id=eSlFAAAAQBAJ&q=western+world+enlightenment&pg=PT24. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- "Muslim Population by Country". Pew Research Center. http://features.pewforum.org/muslim-population/.

- "Preface", The Future of the Global Muslim Population (Pew Research Center), 27 January 2011, http://pewforum.org/future-of-the-global-muslim-population-preface.aspx, retrieved 6 August 2014

- "Executive Summary". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. http://www.pewforum.org/2011/01/27/the-future-of-the-global-muslim-population.

- "Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country". Pew Research Center. http://features.pewforum.org/global-christianity/total-population-percentage.php.

- "Turmoil in the world of Islam". 14 June 2014. http://www.deccanchronicle.com/140614/commentary-op-ed/article/turmoil-world-islam.

- "What is each country's second-largest religious group?". http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/22/what-is-each-countrys-second-largest-religious-group/.

- "Muslim-Majority Countries". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. http://pewforum.org/future-of-the-global-muslim-population-muslim-majority.aspx.

- "Islamic Countries Of The World" (in en). WorldAtlas. 21 February 2018. http://www.worldatlas.com/articles/islamic-countries-in-the-world.html.

- "93 years pass since establishment of first democratic republic in the east – Azerbaijan Democratic Republic". Azerbaijan Press Agency. http://en.apa.az/news.php?id=148210.

- Kazemzadeh (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia: 1917–1921. The New York Philosophical Library. pp. 124, 222, 229, 269–70. ISBN 978-0-8305-0076-5.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (2004). Russian Azerbaijan, 1905–1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-521-52245-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=cozSOSsv7ZsC&pg=129. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Ebaugh, Helen Rose (1 December 2009). The Gülen Movement: A Sociological Analysis of a Civic Movement Rooted in Moderate Islam. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781402098949. https://books.google.com/books?id=MWEePOkKpkoC&q=false&pg=PA116. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- See: Esposito (2004), p. 84Template:Cnf Lapidus (2002), pp. 502–07, 845Template:Cnf Lewis (2003), p. 100Template:Cnf

- 1906 Constitution of Imperial Iran: Article 1 – "The official religion of Persia is Islám, according to the orthodox Já'farí doctrine of the Ithna 'Ashariyya (Church of the Twelve Imáms), which faith 1 the Sháh of Persia must profess and promote."

- "Islam: Governing Under Sharia" (in en). https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/islam-governing-under-sharia.

- "Constitution of Afghanistan 2004". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Afghanistan_2004.

- "Islamic Republic of Iran Constitution". http://www.iranonline.com/iran/iran-info/government/constitution-1.html.

- "Mauritania's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2012". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Mauritania_2012.pdf.

- "The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan". http://www.pakistani.org/pakistan/constitution/.

- "Basic Law of Saudi Arabia". http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/sa00000_.html.

- "Yemen's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2001". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Yemen_2001.pdf?lang=en.

- "Of the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria". http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/local_algeria.pdf.

- The constitution of Bangladesh declares Islam as the state religion, but also guarantees equal rights and treatment for other religions, and separation of government and religion.[151][152]

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/brunei/.

- "Comoros's Constitution of 2001 with Amendments through 2009". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Comoros_2009.pdf.

- "Egypt's Constitution of 2014". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Egypt_2014.pdf.

- "Constitution of Iraq". http://www.iraqinationality.gov.iq/attach/iraqi_constitution.pdf.

- "Jordan country report" , The World Factbook, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, 24 August 2012 https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/jordan/

- "International Religious Freedom Report". 2002. https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2002/14005.htm.

- "Libya's Constitution of 2011 with Amendments through 2012". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Libya_2012.pdf?lang=en.

- "Constitution of Malaysia". http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/malaysia.pdf.

- "Constitution of the Republic of Maldives 2008". http://www.presidencymaldives.gov.mv/Documents/ConstitutionOfMaldives.pdf.

- "Morocco's Constitution of 2011". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Morocco_2011.pdf?lang=en.

- "Archived copy". https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL(2009)008-e.

- "Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Somalia_2012?lang=en.

- "Tunisia's Constitution of 2014". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014.pdf?lang=en.

- "United Arab Emirates's Constitution of 1971 with Amendments through 2009". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/United_Arab_Emirates_2009.pdf?lang=en.

- "Albania – Constitution". ICL. http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/al00000_.html#A007_.

- "Article 7.1 of Constitution". http://azerbaijan.az/portal/General/Constitution/doc/constitution_e.pdf.

- null

- "Article 31 of Constitution". http://www.chr.up.ac.za/hr_docs/constitutions/docs/Burkina%20FasoC%20%28englishsummary%29%28rev%29.doc.

- "Article 1 of Constitution". http://www.chr.up.ac.za/hr_docs/constitutions/docs/ChadC%20%28english%20summary%29%28rev%29.doc.

- "The Gambia 2014 International Religious Freedom Report". https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/238430.pdf.

- Article 1 of Constitution http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/cafrad/unpan002994.pdf

- "Article 1 of Constitution". http://www.cicr.org/ihl-nat.nsf/162d151af444ded44125673e00508141/8ff8cad34667b579c1257083002a6fa8/$FILE/Constitution%20Guinea%20Bissau.doc.

- Kapoor, Kanupriya (21 Jun 2019). "Exclusive: After bruising election, Indonesia to vet public servants to identify Islamists". https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-politics-islamism-exclusive-idUSKCN1TM0T8.

- "The Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan". http://www.akorda.kz/en/category/konstituciya.

- Republic of Kosovo constitution , Republic of Kosovo constitution, http://www.kushtetutakosoves.info/?cid=2,247

- "Article 1 of Constitution". http://www.coe.int/T/E/Legal_Affairs/Legal_co-operation/Foreigners_and_citizens/Nationality/Documents/National_legislation/Kyrgyzstan%20Constitution%20of%20the%20Kyrghyz%20Republic.asp.

- "Preamble of Constitution". http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/Mali.pdf.

- "Niger". 1 Dec 2020. https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-report-on-international-religious-freedom/niger/.

- "Nigerian Constitution". http://www.nigeria-law.org/ConstitutionOfTheFederalRepublicOfNigeria.htm#Powers_of_Federal_Republic_of_Nigeria.

- "Senegal". 14 September 2007. https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2007/90117.htm.

- Timothy J. Demy Ph.D., Jeffrey M. Shaw Ph.D. (2019). Religion and Contemporary Politics: A Global Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 180. ISBN 978-1-4408-3933-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=vt-vDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA180.

- "Sudan ends 30 years of Islamic law by separating religion, state". https://gulfnews.com/world/africa/sudan-ends-30-years-of-islamic-law-by-separating-religion-state-1.1599359147751.

- Aldoughli, Rahaf (11 Aug 2020). "Departing ‘Secularism’: boundary appropriation and extension of the Syrian state in the religious domain since 2011". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (Informa UK Limited): 1–26. doi:10.1080/13530194.2020.1805299. ISSN 1353-0194. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F13530194.2020.1805299

- "Tajikistan's Constitution of 1994 with Amendments through 2003". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tajikistan_2003.pdf?lang=en.

- "Article 2 of Constitution". http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/anayasa.htm.

- "Constitution of Turkmenistan". http://www.uta.edu/cpsees/TURKCON.htm.

- "Uzbekistan's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 2011". https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Uzbekistan_2011.pdf?lang=en.

- "Amman Message". http://ammanmessage.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=15&Itemid=29&limit=1&limitstart=1.

- "Benazir Bhutto: Daughter of Tragedy" by Muhammad Najeeb, Hasan Zaidi, Saurabh Shulka and S. Prasannarajan, India Today, 7 January 2008

- "A Wake-Up Call: Milestones of Islamic History – IslamOnline.net – Art & Culture". 17 February 2011. http://www.islamonline.net/servlet/Satellite?c=Article_C&cid=1212925100226&pagename=Zone-English-ArtCulture/ACELayout.

- "Executive Summary". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/09/muslims-and-islam-key-findings-in-the-u-s-and-around-the-world/.

- "The World Factbook". CIA Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/world/.

- "Muslim-Majority Countries". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. http://pewforum.org/future-of-the-global-muslim-population-muslim-majority.aspx.

- Khan, Nichola (2016). Cityscapes of Violence in Karachi: Publics and Counterpublics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190869786. "... With a population of over 23 million Karachi is also the world's largest Muslim city, the world's seventh largest conurbation ..."

- Adrian Cybriwsky, Roman (2015). Global Happiness: A Guide to the Most Contented (and Discontented) Places around the Globe: A Guide to the Most Contented (and Discontented) Places around the Globe. ABC-CLIO. p. 179. ISBN 9781440835575. "Karachi is the largest city in Pakistan, the second-largest city in the world when "city" is defined by official municipal limits, the largest city in the Muslim world, and the world's seventh-largest metropolitan area."

- "Comparison Chart of Sunni and Shia Islam". ReligionFacts. http://www.religionfacts.com/islam/comparison_charts/islamic_sects.htm.

- ANALYSIS (7 October 2009). "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. http://www.pewforum.org/Mapping-the-Global-Muslim-Population.aspx.

- "The World Factbook". https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/iran/.

- "Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan – Presidential Library – Religion". http://files.preslib.az/projects/remz/pdf_en/atr_din.pdf.

- John Esposito, The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Oxford University Press 2003

- "The population of Shia: How many Shia are there in the world?". http://www.islamicweb.com/beliefs/cults/shia_population.htm.

- "Shi'a". http://philtar.ucsm.ac.uk/encyclopedia/islam/shia/shia.html.

- "Pew Forum on Religious & Public life". http://www.pewforum.org/

- "Country Profile: Pakistan". Library of Congress. February 2005. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Pakistan.pdf. "Religion: The overwhelming majority of the population (96.3 percent) is Muslim, of whom approximately 97 percent are Sunni and 3 percent Shia."

- "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". 9 August 2012. http://www.pewforum.org/2012/08/09/the-worlds-muslims-unity-and-diversity-executive-summary/. "On the other hand, in Pakistan, where 6% of the survey respondents identify as Shia, Sunni attitudes are more mixed: 50% say Shias are Muslims, while 41% say they are not."