The outbreak of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has again emphasized the significance of developing rapid and highly sensitive testing tools for quickly identifying infected patients. The current reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) diagnostic techniques can satisfy the required sensitivity and specificity, the inherent disadvantages with time-consuming, sophisticated equipment and professional operators limit its application scopes. Compared with traditional detection techniques, optical biosensors based on nanomaterials/nanostructures have received much interest in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 due to the high sensitivity, high accuracy, and fast response.

- optical biosensors

- SARS-CoV-2 detection

- point-of-care diagnostics

1. Introduction

2. Potential Optical Biosensors

3. Fluorescence Biosensor for SARS-CoV-2 Diagnosis

3.1. FRET Biosensors for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

3.2. NIR Biosensors for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

3.3. Multi-Modal Biosensors for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/bios12100862

References

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. Addendum: A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 588, E6.

- Gilmutdinova, I.R.; Yakovlev, M.Y.; Eremin, P.S.; Fesun, A.D. Prospects of plasmapheresis for patients with severe COVID-19. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2020, 30, 9165.

- Orooji, Y.; Sohrabi, H.; Hemmat, N.; Oroojalian, F.; Baradaran, B.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Mohaghegh, M.; Karimi-Maleh, H. An overview on SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and other human coronaviruses and their detection capability via amplification assay, chemical sensing, biosensing, immunosensing, and clinical assays. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 18.

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6.

- Xue, X.; Ball, J.K.; Alexander, C.; Alexander, M.R. All surfaces are not equal in contact transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Matter 2020, 3, 1433–1441.

- Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; Sehgal, K.; Nair, N.; Mahajan, S.; Sehrawat, T.S.; Bikdeli, B.; Ahluwalia, N.; Ausiello, J.C.; Wan, E.Y.; et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1017–1032.

- Fakhoury, H.M.A.; Kvietys, P.R.; Shakir, I.; Shams, H.; Grant, W.B.; Alkattan, K. Lung-Centric Inflammation of COVID-19: Potential Modulation by Vitamin D. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2216.

- Song, F.; Shen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yang, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, A.; Li, C.; Wan, Y.; Li, J. Botulinum toxin as an ultrasensitive reporter for bacterial and SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 176, 112953.

- Roda, A.; Cavalera, S.; Di Nardo, F.; Calabria, D.; Rosati, S.; Simoni, P.; Colitti, B.; Baggiani, C.; Roda, M.; Anfossi, L. Dual lateral flow optical/chemiluminescence immunosensors for the rapid detection of salivary and serum IgA in patients with COVID-19 disease. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 172, 112765.

- Torres, M.D.T.; de Araujo, W.R.; de Lima, L.F.; Ferreira, A.L.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Low-cost biosensor for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 at the point of care. Matter 2021, 4, 2403–2416.

- Duan, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ge, X.; Fan, R.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Osman, R.A.; et al. Dual-detection fluorescent immunochromatographic assay for quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD-ACE2 blocking neutralizing antibody. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 199, 113883.

- Chen, W.; Cai, B.; Geng, Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, X. Reducing False Negatives in COVID-19 Testing by Using Microneedle-Based Oropharyngeal Swabs. Matter 2020, 3, 1589–1600.

- Li, Z.; Yi, Y.; Luo, X.; Xiong, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, R.; Wang, Y.; Hu, B.; Chen, W.; et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1518–1524.

- Bahadır, E.B.; Sezgintürk, M.K. Lateral flow assays: Principles, designs and labels. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 82, 286–306.

- Li, H.; Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Qi, Y.J.; Chen, J.; Ma, Y.Y.; Liu, F.J.; Lai, K.S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. A new and rapid approach for detecting COVID-19 based on S1 protein fragments. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e90.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Su, M.; Sun, Y.; Ponkratova, E.; Tan, S.-J.; Pan, Q.; Chen, B.; Li, Z.; Cai, Z.; et al. Self-assembled 1D nanostructures for direct nanoscale detection and biosensing. Matter 2022, 5, 1865–1876.

- Sheervalilou, R.; Shirvaliloo, M.; Sargazi, S.; Shirvalilou, S.; Shahraki, O.; Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi, Y.; Sarhadi, A.; Nazarlou, Z.; Ghaznavi, H.; Khoei, S. Application of nanobiotechnology for early diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 2615–2624.

- Saylan, Y.; Erdem, O.; Unal, S.; Denizli, A. An Alternative Medical Diagnosis Method: Biosensors for Virus Detection. Biosensors 2019, 9, 65.

- Soler, M.; Estevez, M.C.; Cardenosa-Rubio, M.; Astua, A.; Lechuga, L.M. How nanophotonic label-free biosensors can contribute to rapid and massive diagnostics of respiratory virus infections: COVID-19 case. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2663–2678.

- Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Deng, Y.; He, N. Point-of-care diagnostics for infectious diseases: From methods to devices. Nano Today 2021, 37, 101092.

- Naikoo, G.A.; Arshad, F.; Hassan, I.U.; Awan, T.; Salim, H.; Pedram, M.Z.; Ahmed, W.; Patel, V.; Karakoti, A.S.; Vinu, A. Nanomaterials-based sensors for the detection of COVID-19: A review. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 7, e10305.

- Thapa, S.; Singh, K.R.; Verma, R.; Singh, J.; Singh, R.P. State-of-the-art smart and intelligent nanobiosensors for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Biosensors 2022, 12, 637.

- Lukose, J.; Chidangil, S.; George, S.D. Optical technologies for the detection of viruses like COVID-19: Progress and prospects. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 178, 113004.

- Khansili, N.; Rattu, G.; Krishna, P.M. Label-free optical biosensors for food and biological sensor applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 265, 35–49.

- Zhou, X.; Xue, Z.; Wang, T. A point-of-care biosensor for rapid and ultra-sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2. Matter 2022, 5, 2402–2404.

- Moitra, P.; Alafeef, M.; Dighe, K.; Frieman, M.B.; Pan, D. Selective naked-eye detection of SARS-CoV-2 mediated by N gene targeted antisense oligonucleotide capped plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7617–7627.

- Alafeef, M.; Dighe, K.; Moitra, P.; Pan, D. Monitoring the viral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in still waterbodies using a lanthanide-doped carbon nanoparticle-based sensor array. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 245–258.

- Lin, C.; Liang, S.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Luo, X. Localized plasmonic sensor for direct identifying lung and colon cancer from the blood. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 211, 114372.

- Qiu, G.; Gai, Z.; Tao, Y.; Schmitt, J.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Wang, J. Dual-functional plasmonic photothermal biosensors for highly accurate severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 detection. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5268–5277.

- Pashchenko, O.; Shelby, T.; Banerjee, T.; Santra, S. A comparison of optical, electrochemical, magnetic, and colorimetric point-of-care biosensors for infectious disease diagnosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1162–1178.

- Huang, R.; He, L.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Jin, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Deng, Y.; He, N. A simple fluorescence aptasensor for gastric cancer exosome detection based on branched rolling circle amplification. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 2445–2451.

- Li, B.; Yu, Q.; Duan, Y. Fluorescent labels in biosensors for pathogen detection. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 82–93.

- Förster, T. Energy migration and fluorescence. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 011002.

- Wu, B.Y.; Yan, X.P. Bioconjugated persistent luminescence nanoparticles for foster resonance energy transfer immunoassay of prostate specific antigen in serum and cell extracts without in situ excitation. Chem. Commu. 2015, 51, 3903–3906.

- Liao, J.; Madahar, V.; Dang, R.; Jiang, L. Quantitative FRET (qFRET) technology for the determination of protein-protein interaction affinity in solution. Molecules 2021, 26, 6339.

- Chen, T.; Shang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Hao, S.; Yang, C. Activators confined upconversion nanoprobe with near-unity forster resonance energy transfer efficiency for ultrasensitive detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2022, 14, 19826–19835.

- Teng, X.; Sun, X.; Pan, W.; Song, Z.; Wang, J. Carbon dots confined in silica nanoparticles for triplet-to-singlet föster resonance energy-transfer-induced delayed fluorescence. ACS. Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 5168–5175.

- Bardajee, G.R.; Zamani, M.; Mahmoodian, H.; Elmizadeh, H.; Yari, H.; Jouyandeh, L.; Shirkavand, R.; Sharifi, M. Capability of novel fluorescence DNA-conjugated CdTe/ZnS quantum dots nanoprobe for COVID-19 sensing. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 269, 120702.

- Gorshkov, K.; Susumu, K.; Chen, J.; Xu, M.; Pradhan, M.; Zhu, W.; Hu, X.; Breger, J.C.; Wolak, M.; Oh, E. Quantum dot-conjugated SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudo-virions enable tracking of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 binding and endocytosis. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12234–12247.

- Bardajee, G.R.; Zamani, M.; Sharifi, M.; Rezanejad, H.; Motallebi, M. Rapid and highly sensitive detection of target DNA related to COVID-19 virus with a fluorescent bio-conjugated probe via a FRET mechanism. J. Fluoresc. 2022, 32, 1959–1967.

- Zhou, S.; Tu, D.; Liu, Y.; You, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Chen, X. Ultrasensitive point-of-care test for tumor marker in human saliva based on luminescence-amplification strategy of lanthanide nanoprobes. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002657.

- Chen, R.; Ren, C.; Liu, M.; Ge, X.; Qu, M.; Zhou, X.; Liang, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, F. Early detection of SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans with aggregation-induced near-infrared emission nanoparticle-labeled lateral flow immunoassay. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 8996–9004.

- Moitra, P.; Alafeef, M.; Dighe, K.; Sheffield, Z.; Dahal, D.; Pan, D. Synthesis and characterisation of N-gene targeted NIR-II fluorescent probe for selective localisation of SARS-CoV-2. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 6229–6232.

- Peters, J.A.; Djanashvili, K.; Geraldes, C.F.G.C.; Platas-Iglesias, C. The chemical consequences of the gradual decrease of the ionic radius along the Ln-series. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 406, 213146.

- Zou, Q.; Huang, P.; Zheng, W.; You, W.; Li, R.; Tu, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, X. Cooperative and non-cooperative sensitization upconversion in lanthanide-doped LiYbF4 nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 6521–6528.

- Liu, Q.; Cheng, S.; Chen, R.; Ke, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, W.; Li, F. Near-infrared lanthanide-doped nanoparticles for a low interference lateral flow immunoassay test. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2020, 12, 4358–4365.

- Guo, J.; Chen, S.; Tian, S.; Liu, K.; Ni, J.; Zhao, M.; Kang, Y.; Ma, X.; Guo, J. 5G-enabled ultra-sensitive fluorescence sensor for proactive prognosis of COVID-19. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 181, 113160.

- Feng, M.; Chen, J.; Xun, J.; Dai, R.; Zhao, W.; Lu, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Sui, G.; Cheng, X. Development of a sensitive immunochromatographic method using lanthanide fluorescent microsphere for rapid serodiagnosis of COVID-19. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2331–2337.

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhai, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhao, H.; Bian, L.; Li, P.; Yu, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG, using lanthanide-doped nanoparticles-based lateral flow immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 7226–7231.

- Hu, R.; Liao, T.; Ren, Y.; Liu, W.; Ma, R.; Wang, X.; Lin, Q.; Wang, G.; Liang, Y. Sensitively detecting antigen of SARS-CoV-2 by NIR-II fluorescent nanoparticles. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 7313–7319.

- Serrano-Aroca, A.; Takayama, K.; Tunon-Molina, A.; Seyran, M.; Hassan, S.S.; Pal Choudhury, P.; Uversky, V.N.; Lundstrom, K.; Adadi, P.; Palu, G.; et al. Carbon-based nanomaterials: Promising antiviral agents to combat COVID-19 in the microbial-resistant era. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 8069–8086.

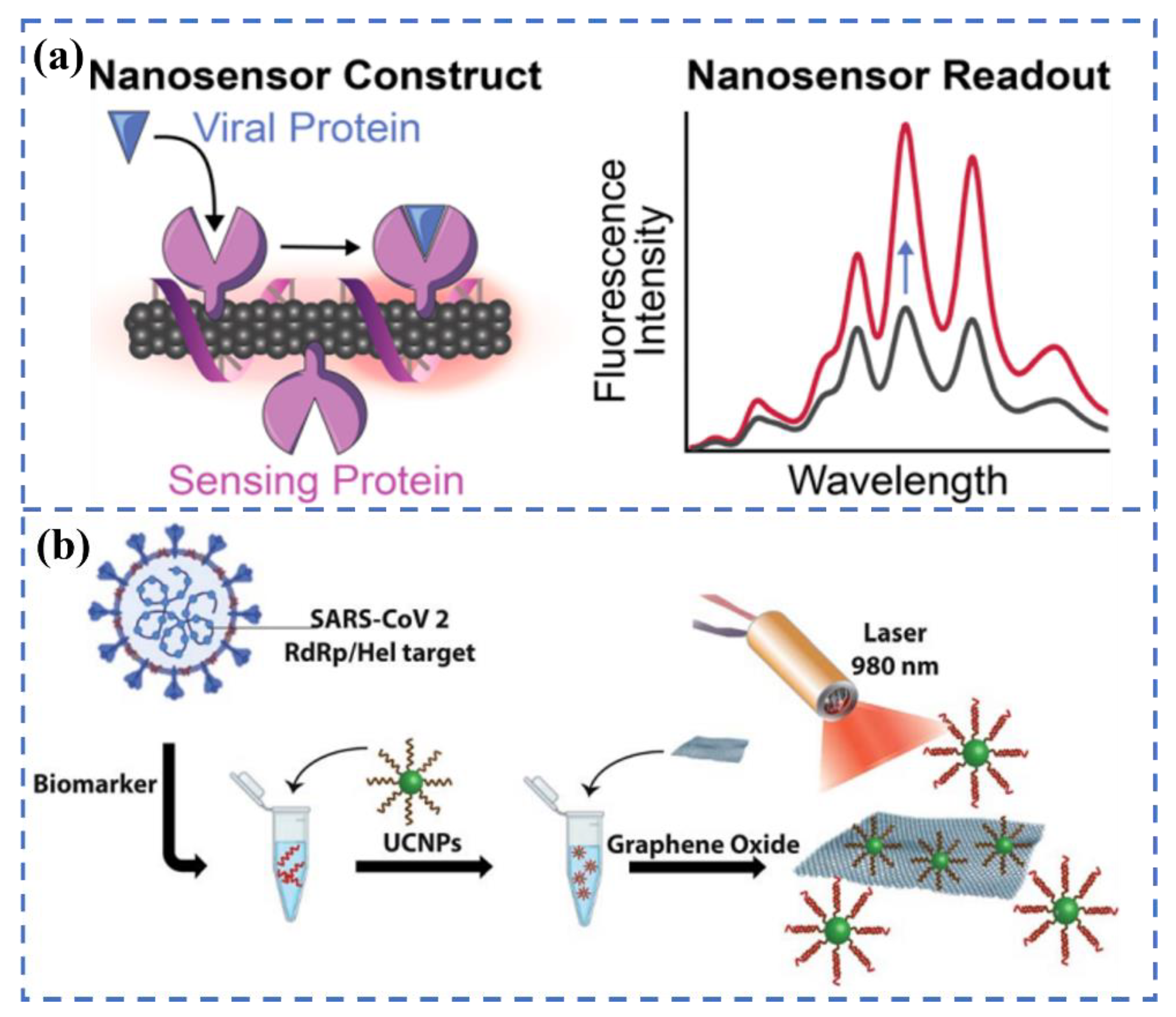

- Pinals, R.L.; Ledesma, F.; Yang, D.; Navarro, N.; Jeong, S.; Pak, J.E.; Kuo, L.; Chuang, Y.C.; Cheng, Y.W.; Sun, H.Y.; et al. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 spike protein detection by carbon nanotube-based near-infrared nanosensors. Nano. Lett. 2021, 21, 2272–2280.

- Alexaki, K.; Kyriazi, M.E.; Greening, J.; Taemaitree, L.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; Brown, T.; Zhang, X.; Muskens, O.L.; Kanaras, A.G. A SARS-CoV-2 sensor based on upconversion nanoparticles and graphene oxide. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 18445–18449.

- Masterson, A.N.; Liyanage, T.; Berman, C.; Kaimakliotis, H.; Johnson, M.; Sardar, R. A novel liquid biopsy-based approach for highly specific cancer diagnostics: Mitigating false responses in assaying patient plasma-derived circulating microRNAs through combined SERS and plasmon-enhanced fluorescence analyses. Analyst 2020, 145, 4173–4180.

- Song, C.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Dong, C.; Wang, L. Colorimetric/SERS dual-mode detection of mercury ion via SERS-Active peroxidase-like NPs. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 310, 127849.

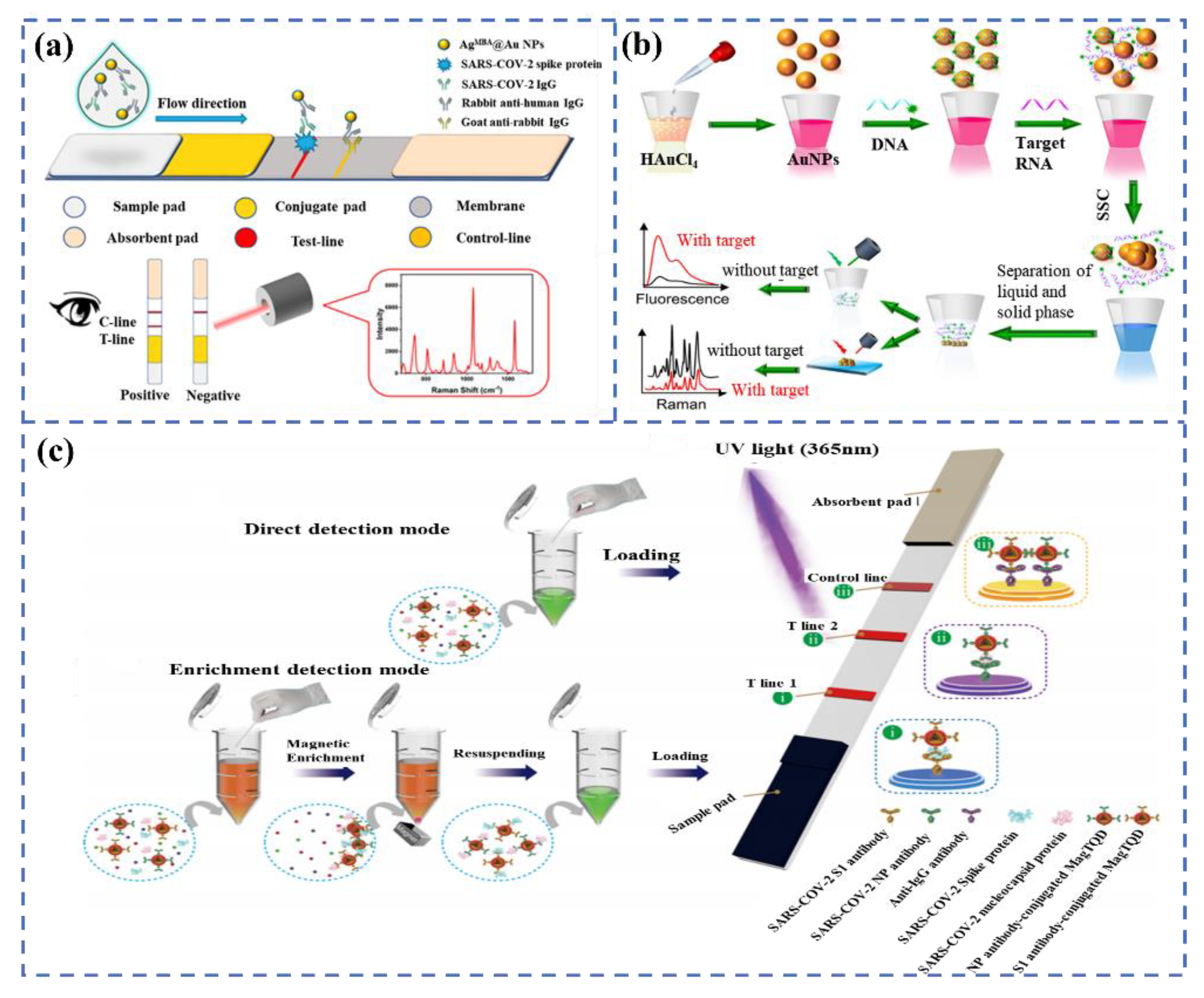

- Han, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Zheng, S.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Xiao, R. Rapid field determination of SARS-CoV-2 by a colorimetric and fluorescent dual-functional lateral flow immunoassay biosensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 351, 130897.

- Liang, P.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, T.; Wen, C.Y.; Tian, Z.; Shang, Y.; Xing, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, J. Ag Nanoparticles with ultrathin au shell-based lateral flow immunoassay for colorimetric and SERS dual-mode detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgG. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 8466–8473.

- Gao, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, C.; Qiang, L.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y. Rapid and sensitive triple-mode detection of causative SARS-CoV-2 virus specific genes through interaction between genes and nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021, 1154, 338330.

- Wang, C.; Cheng, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Zheng, S.; Rong, Z.; Wang, S. Ultrasensitive and simultaneous detection of two specific SARS-CoV-2 antigens in human specimens using direct/enrichment dual-mode fluorescence lateral flow immunoassay. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2021, 13, 40342–40353.

- Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Gu, B.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, L.; Cheng, X.; Wang, S. Sensitive and simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM/IgG using lateral flow immunoassay based on dual-mode quantum dot nanobeads. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 15542–15549.