Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are transcription factors that respond to decreases in available oxygen in the cellular environment, or hypoxia.

- hypoxia

- hifs

- transcription factors

1. Discovery

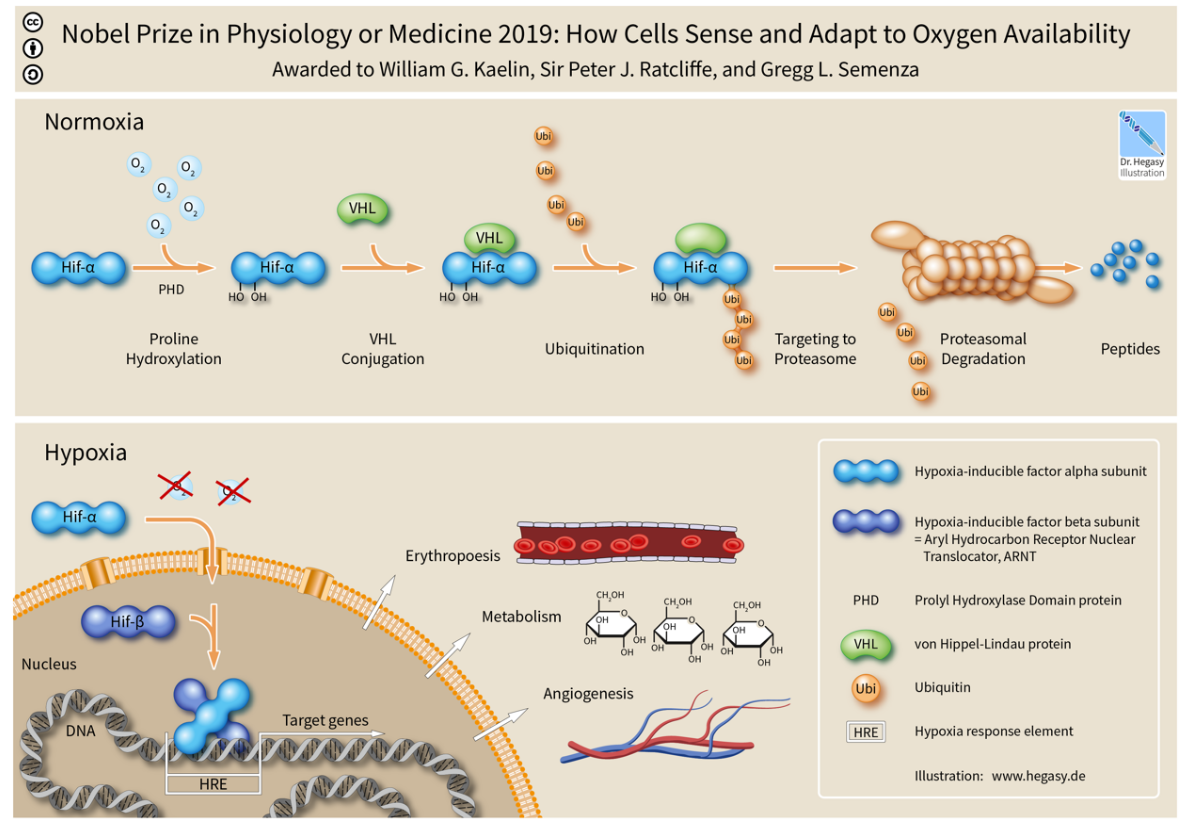

The HIF transcriptional complex was discovered in 1995 by Gregg L. Semenza and postdoctoral fellow Guang Wang.[1][2][3] In 2016, William Kaelin Jr., Peter J. Ratcliffe and Gregg L. Semenza were presented the Lasker Award for their work in elucidating the role of HIF-1 in oxygen sensing and its role in surviving low oxygen conditions.[4] In 2019, the same three individuals were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work in elucidating how HIF senses and adapts cellular response to oxygen availability.[5]

2. Structure

Most, if not all, oxygen-breathing species express the highly conserved transcriptional complex HIF-1, which is a heterodimer composed of an alpha and a beta subunit, the latter being a constitutively-expressed aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT).[6][7] HIF-1 belongs to the PER-ARNT-SIM (PAS) subfamily of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors. The alpha and beta subunit are similar in structure and both contain the following domains:[8][9][10]

- N-terminus – a bHLH domain for DNA binding

- central region – Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) domain, which facilitates heterodimerization

- C-terminus – recruits transcriptional coregulatory proteins

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3. Members

The following are members of the human HIF family:

| Member | Gene | Protein |

|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α | HIF1A | hypoxia-inducible factor 1, alpha subunit |

| HIF-1β | ARNT | aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator |

| HIF-2α | EPAS1 | endothelial PAS domain protein 1 |

| HIF-2β | ARNT2 | aryl-hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 2 |

| HIF-3α | HIF3A | hypoxia inducible factor 3, alpha subunit |

| HIF-3β | ARNT3 | aryl-hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 3 |

4. Function

HIF1α expression in haematopoietic stem cells explains the quiescence nature of stem cells[13] for being metabolically maintaining at a low rate so as to preserve the potency of stem cells for long periods in a life cycle of an organism.

The HIF signaling cascade mediates the effects of hypoxia, the state of low oxygen concentration, on the cell. Hypoxia often keeps cells from differentiating. However, hypoxia promotes the formation of blood vessels, and is important for the formation of a vascular system in embryos and tumors. The hypoxia in wounds also promotes the migration of keratinocytes and the restoration of the epithelium.[14]

In general, HIFs are vital to development. In mammals, deletion of the HIF-1 genes results in perinatal death. HIF-1 has been shown to be vital to chondrocyte survival, allowing the cells to adapt to low-oxygen conditions within the growth plates of bones. HIF plays a central role in the regulation of human metabolism.[15]

5. Mechanism

The alpha subunits of HIF are hydroxylated at conserved proline residues by HIF prolyl-hydroxylases, allowing their recognition and ubiquitination by the VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase, which labels them for rapid degradation by the proteasome.[16][17] This occurs only in normoxic conditions. In hypoxic conditions, HIF prolyl-hydroxylase is inhibited, since it utilizes oxygen as a cosubstrate.[18][19]

Inhibition of electron transfer in the succinate dehydrogenase complex due to mutations in the SDHB or SDHD genes can cause a build-up of succinate that inhibits HIF prolyl-hydroxylase, stabilizing HIF-1α. This is termed pseudohypoxia.

HIF-1, when stabilized by hypoxic conditions, upregulates several genes to promote survival in low-oxygen conditions. These include glycolysis enzymes, which allow ATP synthesis in an oxygen-independent manner, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis. HIF-1 acts by binding to Hypoxia-responsive elements (HREs) in promoters that contain the sequence NCGTG (where N is either A or G). Recent work from the laboratories of Sónia Rocha and William Kaelin Jr. demonstrates that Hypoxia modulates histone methylation and reprograms chromatin [20] This paper was published back-to-back with that of 2019 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine winner for Medicine William Kaelin Jr.[21] This work was highlighted in an independent editorial.[22]

It has been shown that muscle A kinase–anchoring protein (mAKAP) organized E3 ubiquitin ligases, affecting stability and positioning of HIF-1 inside its action site in the nucleus. Depletion of mAKAP or disruption of its targeting to the perinuclear (in cardiomyocytes) region altered the stability of HIF-1 and transcriptional activation of genes associated with hypoxia. Thus, "compartmentalization" of oxygen-sensitive signaling components may influence the hypoxic response.[23]

The advanced knowledge of the molecular regulatory mechanisms of HIF1 activity under hypoxic conditions contrast sharply with the paucity of information on the mechanistic and functional aspects governing NF-κB-mediated HIF1 regulation under normoxic conditions. However, HIF-1α stabilization is also found in non-hypoxic conditions through an, until recently, unknown mechanism. It was shown that NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) is a direct modulator of HIF-1α expression in the presence of normal oxygen pressure. siRNA (small interfering RNA) studies for individual NF-κB members revealed differential effects on HIF-1α mRNA levels, indicating that NF-κB can regulate basal HIF-1α expression. Finally, it was shown that, when endogenous NF-κB is induced by TNFα (tumour necrosis factor α) treatment, HIF-1α levels also change in an NF-κB-dependent manner.[24] HIF-1 and HIF-2 have different physiological roles. HIF-2 regulates erythropoietin production in adult life.[25]

5.1. Repair or Regeneration

In normal circumstances after injury HIF-1a is degraded by prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs). In June 2015, scientists found that the continued up-regulation of HIF-1a via PHD inhibitors regenerates lost or damaged tissue in mammals that have a repair response; and the continued down-regulation of Hif-1a results in healing with a scarring response in mammals with a previous regenerative response to the loss of tissue. The act of regulating HIF-1a can either turn off, or turn on the key process of mammalian regeneration.[26][27]

6. As a Therapeutic Target

6.1. Anemia

Recently, several drugs that act as selective HIF prolyl-hydroxylase inhibitors have been developed.[28][29] The most notable compounds are: Roxadustat (FG-4592);[30] Vadadustat (AKB-6548),[31] Daprodustat (GSK1278863),[32] Desidustat (ZYAN-1),[33] and Molidustat (Bay 85-3934),[34] all of which are intended as orally acting drugs for the treatment of anemia.[35] Other significant compounds from this family, which are used in research but have not been developed for medical use in humans, include MK-8617,[36] YC-1,[37] IOX-2,[38] 2-methoxyestradiol,[39] GN-44028,[40] AKB-4924,[41] Bay 87-2243,[42] FG-2216[43] and FG-4497.[44] By inhibiting prolyl-hydroxylase enzyme, the stability of HIF-2α in the kidney is increased, which results in an increase in endogenous production of erythropoietin.[45] Both FibroGen compounds made it through to Phase II clinical trials, but these were suspended temporarily in May 2007 following the death of a trial participant taking FG-2216 from fulminant hepatitis (liver failure), however it is unclear whether this death was actually caused by FG-2216. The hold on further testing of FG-4592 was lifted in early 2008, after the FDA reviewed and approved a thorough response from FibroGen.[46] Roxadustat, vadadustat, daprodustat and molidustat have now all progressed through to Phase III clinical trials for treatment of renal anemia.[30][31][32]

6.2. Inflammation and Cancer

In other scenarios and in contrast to the therapy outlined above, recent research suggests that HIF induction in normoxia is likely to have serious consequences in disease settings with a chronic inflammatory component.[47][48][49] It has also been shown that chronic inflammation is self-perpetuating and that it distorts the microenvironment as a result of aberrantly active transcription factors. As a consequence, alterations in growth factor, chemokine, cytokine, and ROS balance occur within the cellular milieu that in turn provide the axis of growth and survival needed for de novo development of cancer and metastasis. These results have numerous implications for a number of pathologies where NF-κB and HIF-1 are deregulated, including rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.[50][51][52][53] Therefore, it is thought that understanding the cross-talk between these two key transcription factors, NF-κB and HIF, will greatly enhance the process of drug development.[24][54]

HIF activity is involved in angiogenesis required for cancer tumor growth, so HIF inhibitors such as phenethyl isothiocyanate and Acriflavine[55] are (since 2006) under investigation for anti-cancer effects.[56][57][58]

6.3. Neurology

Research conducted on mice suggests that stabilizing HIF using an HIF prolyl-hydroxylase inhibitor enhances hippocampal memory, likely by increasing erythropoietin expression.[59] HIF pathway activators such as ML-228 may have neuroprotective effects and are of interest as potential treatments for stroke and spinal cord injury.[60][61]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:Hypoxia-inducible_factors

References

- "Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 270 (3): 1230–7. January 1995. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. PMID 7836384. https://dx.doi.org/10.1074%2Fjbc.270.3.1230

- "Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92 (12): 5510–4. June 1995. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. PMID 7539918. Bibcode: 1995PNAS...92.5510W. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=41725

- "Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors (HIF) as important regulators of tumor physiology". Cancer Treatment and Research 117: 219–48. 2004. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8871-3_14. ISBN 978-1-4613-4699-9. PMID 15015563. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-1-4419-8871-3_14

- "Oxygen sensing – an essential process for survival". Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. Albert And Mary Lasker Foundation. 2016. http://www.laskerfoundation.org/awards/show/oxygen-sensing-essential-process-survival/.

- "How cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability". The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2019. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB. 7 October 2019. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2019/press-release/.

- "Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92 (12): 5510–4. June 1995. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. PMID 7539918. Bibcode: 1995PNAS...92.5510W. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=41725

- "Dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (30): 17771–8. July 1996. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.30.17771. PMID 8663540. https://dx.doi.org/10.1074%2Fjbc.271.30.17771

- "PAS domain S-boxes in Archaea, Bacteria and sensors for oxygen and redox". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 22 (9): 331–3. September 1997. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01110-9. PMID 9301332. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0968-0004%2897%2901110-9

- "PAS: a multifunctional domain family comes to light". Current Biology 7 (11): R674–7. November 1997. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00352-6. PMID 9382818. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0960-9822%2806%2900352-6

- "Functions of the Per/ARNT/Sim domains of the hypoxia-inducible factor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (43): 36047–54. October 2005. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501755200. PMID 16129688. https://dx.doi.org/10.1074%2Fjbc.M501755200

- "Structure of an HIF-1alpha -pVHL complex: hydroxyproline recognition in signaling". Science 296 (5574): 1886–9. June 2002. doi:10.1126/science.1073440. PMID 12004076. Bibcode: 2002Sci...296.1886M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1073440

- "Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (8): 5367–72. April 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.082117899. PMID 11959990. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.5367F. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=122775

- "Anaerobic Glycolysis and HIF1α Expression in Haematopoietic Stem Cells Explains Its Quiescence Nature". Journal of Stem Cells 10 (2): 97–106. 2015. PMID 27125138. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27125138

- "The magic of the hypoxia-signaling cascade". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 65 (7–8): 1133–49. April 2008. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-7472-0. PMID 18202826. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00018-008-7472-0

- "Regulation of human metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (28): 12722–7. July 2010. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002339107. PMID 20616028. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..10712722F. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2906567

- "The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis". Nature 399 (6733): 271–5. May 1999. doi:10.1038/20459. PMID 10353251. Bibcode: 1999Natur.399..271M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F20459

- Perkel, Jeffrey (May 2001). "Seeking a Cellular Oxygen Sensor". The Scientist. https://www.the-scientist.com/research/seeking-a-cellular-oxygen-sensor-54701. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "Hydroxylation of HIF-1: oxygen sensing at the molecular level". Physiology 19 (4): 176–82. August 2004. doi:10.1152/physiol.00001.2004. PMID 15304631. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/c7526355ac1f22e25e25a6cd8a3ca7673ef20ef3.

- Russo, Eugene (April 2003). "Discovering HIF Regulation". The Scientist. https://www.the-scientist.com/hot-paper/discovering-hif-regulation-51758. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "Hypoxia induces rapid changes to histone methylation and reprograms chromatin.". Science 363 (6432): 1222–1226. 2019. doi:10.1126/science.aau5870. PMID 30872526. Bibcode: 2019Sci...363.1222B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.aau5870

- "Histone demethylase KDM6A directly senses oxygen to control chromatin and cell fate.". Science 363 (6432): 1217–1222. 2019. doi:10.1126/science.aaw1026. PMID 30872525. Bibcode: 2019Sci...363.1217C. http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi-fe201903259863.

- "Histone modifiers are oxygen sensors.". Science 363 (6432): 1148–1149. 2019. doi:10.1126/science.aaw8373. PMID 30872506. Bibcode: 2019Sci...363.1148G. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.aaw8373

- "mAKAP compartmentalizes oxygen-dependent control of HIF-1alpha". Science Signaling 1 (51): ra18. December 2008. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000026. PMID 19109240. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2828263

- "Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by NF-kappaB". The Biochemical Journal 412 (3): 477–84. June 2008. doi:10.1042/BJ20080476. PMID 18393939. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2474706

- "Hypoxic regulation of erythropoiesis and iron metabolism". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 299 (1): F1–13. July 2010. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00174.2010. PMID 20444740. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2904169

- eurekalert.org staff (3 June 2015). "Scientist at LIMR leads study demonstrating drug-induced tissue regeneration". Lankenau Institute for Medical Research (LIMR). http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2015-06/mlhl-sal060215.php. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "Drug-induced regeneration in adult mice". Science Translational Medicine 7 (290): 290ra92. June 2015. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3010228. PMID 26041709. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4687906

- "Hydroxylation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors and chemical compounds targeting the HIF-alpha hydroxylases". Current Medicinal Chemistry 14 (17): 1853–62. 2007. doi:10.2174/092986707781058850. PMID 17627521. https://dx.doi.org/10.2174%2F092986707781058850

- "HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors for the treatment of renal anaemia and beyond". Nature Reviews. Nephrology 12 (3): 157–68. March 2016. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2015.193. PMID 26656456. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/253687.

- "A New Approach to the Management of Anemia in CKD Patients: A Review on Roxadustat". Advances in Therapy 34 (4): 848–853. 2017. doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0508-9. PMID 28290095. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs12325-017-0508-9

- "Vadadustat, a novel oral HIF stabilizer, provides effective anemia treatment in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease". Kidney International 90 (5): 1115–1122. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.07.019. PMID 27650732. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.kint.2016.07.019

- "Discovery and Preclinical Characterization of GSK1278863 (Daprodustat), a Small Molecule Hypoxia Inducible Factor-Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitor for Anemia". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 363 (3): 336–347. 2017. doi:10.1124/jpet.117.242503. PMID 28928122. https://dx.doi.org/10.1124%2Fjpet.117.242503

- "Phase I Clinical Study of ZYAN1, A Novel Prolyl-Hydroxylase (PHD) Inhibitor to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics Following Oral Administration in Healthy Volunteers". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 57 (1): 87–102. May 2017. doi:10.1007/s40262-017-0551-3. PMID 28508936. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5766731

- "Mimicking hypoxia to treat anemia: HIF-stabilizer BAY 85-3934 (Molidustat) stimulates erythropoietin production without hypertensive effects". PLOS ONE 9 (11): e111838. 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111838. PMID 25392999. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9k1838F. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4230943

- "The latest advances in kidney diseases and related disorders". Drug News & Perspectives 20 (10): 647–54. December 2007. PMID 18301799. http://journals.prous.com/journals/servlet/xmlxsl/pk_journals.xml_summaryn_pr?p_JournalId=3&p_RefId=3919.

- "Discovery of N-[Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-4-hydroxy-2-(pyridazin-3-yl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide (MK-8617), an Orally Active Pan-Inhibitor of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase 1-3 (HIF PHD1-3) for the Treatment of Anemia". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 59 (24): 11039–11049. December 2016. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01242. PMID 28002958. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Facs.jmedchem.6b01242

- "YC-1: a potential anticancer drug targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 95 (7): 516–25. April 2003. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.7.516. PMID 12671019. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Fjnci%2F95.7.516

- "Impairment of hypoxia-induced HIF-1α signaling in keratinocytes and fibroblasts by sulfur mustard is counteracted by a selective PHD-2 inhibitor". Archives of Toxicology 90 (5): 1141–50. May 2016. doi:10.1007/s00204-015-1549-y. PMID 26082309. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00204-015-1549-y

- "Cancer therapeutic agents targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1". Current Medicinal Chemistry 18 (21): 3168–89. 2011. doi:10.2174/092986711796391606. PMID 21671859. https://dx.doi.org/10.2174%2F092986711796391606

- "Discovery of Indenopyrazoles as a New Class of Hypoxia Inducible Factor (HIF)-1 Inhibitors". ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 4 (2): 297–301. February 2013. doi:10.1021/ml3004632. PMID 24900662. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4027554

- "A new pharmacological agent (AKB-4924) stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and increases skin innate defenses against bacterial infection". Journal of Molecular Medicine 90 (9): 1079–89. September 2012. doi:10.1007/s00109-012-0882-3. PMID 22371073. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3606899

- "Hypoxia-Dependent HIF-1 Activation Impacts on Tissue Remodeling in Graves' Ophthalmopathy-Implications for Smoking". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 101 (12): 4834–4842. December 2016. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-1279. PMID 27610652. https://dx.doi.org/10.1210%2Fjc.2016-1279

- "Hypoxia-inducible factor stabilizers and other small-molecule erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in current and preventive doping analysis". Drug Test Anal 4 (11): 830–45. 2012. doi:10.1002/dta.390. PMID 22362605. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fdta.390

- "FG-4497: a new target for acute respiratory distress syndrome?". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 9 (4): 405–9. August 2015. doi:10.1586/17476348.2015.1065181. PMID 26181437. https://dx.doi.org/10.1586%2F17476348.2015.1065181

- "HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibition results in endogenous erythropoietin induction, erythrocytosis, and modest fetal hemoglobin expression in rhesus macaques". Blood 110 (6): 2140–7. September 2007. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-02-073254. PMID 17557894. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1976368

- "The FDA Accepts the Complete Response for Clinical Holds of FG-2216/FG-4592 for the Treatment of Anemia". http://www.astellas.com/en/corporate/news/pdf/080402_eg.pdf.

- "Targeting hypoxia signalling for the treatment of ischaemic and inflammatory diseases". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 13 (11): 852–69. November 2014. doi:10.1038/nrd4422. PMID 25359381. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4259899

- "AMPK and HIF signaling pathways regulate both longevity and cancer growth: the good news and the bad news about survival mechanisms". Biogerontology 17 (4): 655–80. August 2016. doi:10.1007/s10522-016-9655-7. PMID 27259535. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10522-016-9655-7

- "Hypoxia-dependent regulation of inflammatory pathways in immune cells". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 126 (10): 3716–3724. October 2016. doi:10.1172/JCI84433. PMID 27454299. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5096820

- "The role of HIF in immunity and inflammation". Molecular Aspects of Medicine 47–48: 24–34. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2015.12.004. PMID 26768963. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.mam.2015.12.004

- "Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) as a Target for Novel Therapies in Rheumatoid Arthritis". Frontiers in Pharmacology 7: 184. 2016. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00184. PMID 27445820. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4921475

- "Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor and metabolic pathways: possible targets of cancer". Cell & Bioscience 7: 62. 2017. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0190-2. PMID 29158891. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5683220

- "Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) in the tumor microenvironment: friend or foe?". Science China Life Sciences 60 (10): 1114–1124. October 2017. doi:10.1007/s11427-017-9178-y. PMID 29039125. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6131113

- "NF-κB and HIF crosstalk in immune responses". The FEBS Journal 283 (3): 413–24. February 2016. doi:10.1111/febs.13578. PMID 26513405. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4864946

- "Acriflavine inhibits HIF-1 dimerization, tumor growth, and vascularization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (42): 17910–5. October 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909353106. PMID 19805192. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10617910L. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2764905

- "In vivo modulation of 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) phosphorylation by watercress: a pilot study". The British Journal of Nutrition 104 (9): 1288–96. November 2010. doi:10.1017/S0007114510002217. PMID 20546646. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3694331

- "Evaluation of HIF-1 inhibitors as anticancer agents". Drug Discovery Today 12 (19–20): 853–9. October 2007. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2007.08.006. PMID 17933687. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.drudis.2007.08.006

- "Inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor 1 for cancer therapy". Molecular Cancer Research 4 (9): 601–5. September 2006. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0235. PMID 16940159. https://dx.doi.org/10.1158%2F1541-7786.MCR-06-0235

- "Hypoxia inducible factor stabilization leads to lasting improvement of hippocampal memory in healthy mice". Behavioural Brain Research 208 (1): 80–4. March 2010. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.010. PMID 19900484. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.bbr.2009.11.010

- "HIF-1α Activation Attenuates IL-6 and TNF-α Pathways in Hippocampus of Rats Following Transient Global Ischemia". Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 39 (2): 511–20. 2016. doi:10.1159/000445643. PMID 27383646. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159%2F000445643

- "Effect of hypoxia-inducible factor-1/vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway on spinal cord injury in rats". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 13 (3): 861–866. March 2017. doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4049. PMID 28450910. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5403438

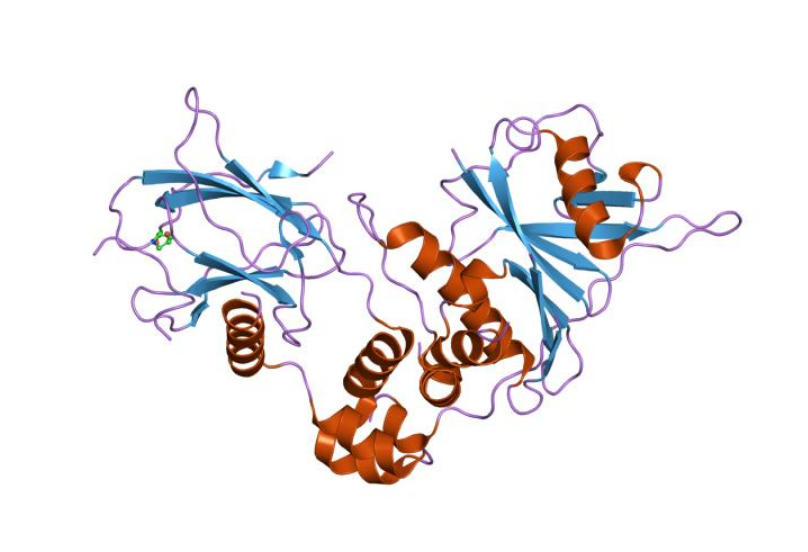

Structure of a HIF-1a-pVHL-ElonginB-ElonginC Complex.[

Structure of a HIF-1a-pVHL-ElonginB-ElonginC Complex.[ Structure of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha subunit.[

Structure of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha subunit.[