In Christian theology, Hell is the place or state into which, by God's definitive judgment, unrepentant sinners pass in the general judgment, or, as some Christians believe, immediately after death (particular judgment). Its character is inferred from teaching in the biblical texts, some of which, interpreted literally, have given rise to the popular idea of Hell. Theologians today generally see Hell as the logical consequence of using free will to reject union with God and, because God will not force conformity, it is not incompatible with God's justice and mercy. Different Hebrew and Greek words are translated as "Hell" in most English-language Bibles. These words include:

- "Sheol" in the Hebrew Bible, and "Hades" in the New Testament. Many modern versions, such as the New International Version, translate Sheol as "grave" and simply transliterate "Hades". It is generally agreed that both sheol and hades do not typically refer to the place of eternal punishment, but to the grave, the temporary abode of the dead, the underworld.

- "Gehenna" in the New Testament, where it is described as a place where both soul and body could be destroyed (Matthew 10:28) in "unquenchable fire" (Mark 9:43). The word is translated as either "Hell" or "Hell fire" in many English versions. Gehenna was a physical location outside the city walls where they burned garbage and where lepers and outcasts were sent, hence the weeping and gnashing of teeth.

- The Greek verb ταρταρῶ (tartarō, derived from Tartarus), which occurs once in the New Testament (in 2 Peter 2:4), is almost always translated by a phrase such as "thrown down to hell". A few translations render it as "Tartarus"; of this term, the Holman Christian Standard Bible states: "Tartarus is a Greek name for a subterranean place of divine punishment lower than Hades."

- theology

- hell

- free will

1. Jewish Background

In ancient Jewish belief, the dead were consigned to Sheol, a place to which all were sent indiscriminately (cf. Genesis 37:35; Numbers 16:30-33; Psalm 86:13; Ecclesiastes 9:10). Sheol was thought of as a place situated below the ground (cf. Ezek. 31:15), a place of darkness, silence and forgetfulness (cf. Job 10:21).[1] By the third to second century BC, the idea had grown to encompass separate divisions in sheol for the righteous and wicked (cf. the Book of Enoch),[2] and by the time of Jesus, some Jews had come to believe that those in Sheol awaited the resurrection of the dead either in comfort (in the bosom of Abraham) or in torment.

In the Greek Septuagint, the Hebrew word Sheol was translated as Hades.[3] the name for the underworld and abode of the dead in Greek mythology. The realm of eternal punishment in Hellenistic mythology was Tartarus, Hades was a form of limbo for the unjudged dead.

By at least the late or saboraic rabbinical period (500-640 CE), Gehinnom was viewed as the place of ultimate punishment, exemplified by the rabbinical statement "the best of medicians are destined to Gehinnom." (M. Kiddushin 4:14); also described in Assumption of Moses and 2 Esdras.[4]

2. New Testament

Three different New Testament words appear in most English translations as "Hell":

| Greek NT | NT occurrences | KJV | NKJV | NASB | NIV | ESV | CEV | NLT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᾅδης (Hades)[5] | 9[6] | Hell (9/10)[7] | Hades (10/10) | Hades (9/9) | Hades (7/9 or 4/9)[8] | Hades (8/9)[9] | death's kingdom (3/9)[10] | grave (6/9)[11] |

| γέεννα (Gehenna)[5] | 12[12] | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell |

| ταρταρῶ (Tartarō̂, verb)[5] | 1[13] | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell | Hell |

The most common New Testament term translated as "Hell" is γέεννα (gehenna), a direct loan of Hebrew גהנום/גהנם (ge-hinnom). Apart from one use in James 3:6, this term is found exclusively in the synoptic gospels.[14][15][16] Gehenna is most frequently described as a place of punishment (e.g., Matthew 5:22, Matthew 18:8-9; Mark 9:43-49); other passages mention darkness and "weeping and gnashing of teeth" (e.g., Matthew 8:12; Matthew 22:13).[15]

Apart from the use of the term gehenna (translated as "Hell" or "Hell fire" in most English translations of the Bible; sometimes transliterated, or translated differently)[17][18][19] the Johannine writings refer to the destiny of the wicked in terms of "perishing", "death" and "condemnation" or "judgment". Paul speaks of "wrath" and "everlasting destruction" (cf. Romans 2:7-9; 2 Thessalonians), while the general epistles use a range of terms and images including "raging fire" (Hebrews 10:27), "destruction" (2 Peter 3:7), "eternal fire" (Jude 7) and "blackest darkness" (Jude 13). The Book of Revelation contains the image of a "lake of fire" and "burning sulphur" where "the devil, the beast, and false prophet" will be "tormented day and night for ever and ever" (Revelation 20:10) along with those who worship the beast or receive its mark (Revelation 14:11).[20]

The New Testament also uses the Greek word hades, usually to refer to the abode of the dead (e.g., Acts 2:31; Revelation 20:13).[2] Only one passage describes hades as a place of torment, the parable of Lazarus and Dives (Luke 16:19-31). Jesus here depicts a wicked man suffering fiery torment in hades, which is contrasted with the bosom of Abraham, and explains that it is impossible to cross over from one to the other. Some scholars believe that this parable reflects the intertestamental Jewish view of hades (or sheol) as containing separate divisions for the wicked and righteous.[2][20] In Revelation 20:13-14 hades is itself thrown into the "lake of fire" after being emptied of the dead.

2.1. Parables of Jesus Concerning the Hereafter

In the eschatological discourse of Matthew 25:31-46, Jesus says that, when the Son of Man comes in his glory, he will separate people from one another as a shepherd separates sheep from goats, and will consign to everlasting fire those who failed to aid "the least of his brothers". This separation is stark, with no explicit provision made for fine gradations of merit or guilt:[21]

Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me. ...whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.—Matthew 25:41–43 (NIV)

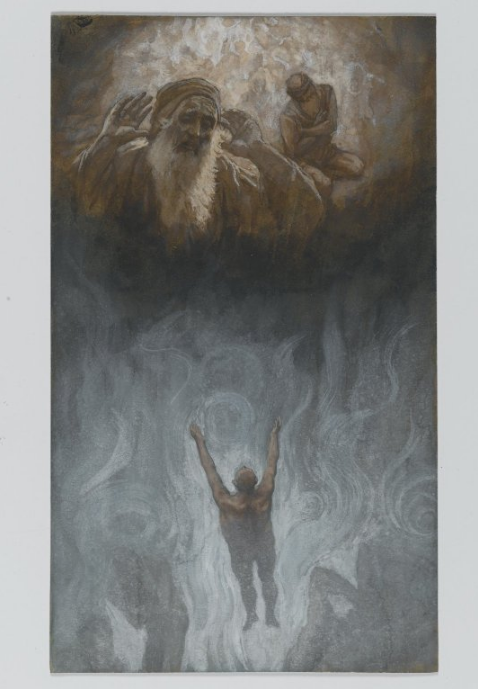

In a parable about "The Rich Man and Lazarus" in Luke 16:19-31, the poor man Lazarus enjoys a blissful repose in the "bosom of Abraham" (Luke 16:22), while the rich man who was happy in life is tormented by fire in Hades (Luke 16:23-24), the two realms being separated by a great chasm (Luke 16:26).

3. Eastern Orthodox Views

Some Eastern Orthodox Christians believe that Heaven and Hell are relations to or experiences of God's just and loving presence.[22][23] There is no created place of divine absence, nor is hell an ontological separation from God.[24] One expression of the Eastern teaching is that hell and heaven are dimensions of God's intensifying presence, as this presence is experienced either as torment or as paradise depending on the spiritual state of a person dwelling with God.[22][25] For one who hates God and by extension hates himself as God's image-bearer, to be encompassed by the divine presence could only result in unspeakable anguish.[26][27][28] Aristotle Papanikolaou[29] and Elizabeth H. Prodromou[30] write in their book Thinking Through Faith: New Perspectives from Orthodox Christian Scholars that for the Eastern Orthodox: "Those theological symbols, heaven and hell, are not crudely understood as spatial destinations but rather refer to the experience of God's presence according to two different modes."[31] Several Eastern Orthodox theologians do describe hell as separation from God, in the sense of being out of fellowship or loving communion. Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov) spoke of "the hell of separation from God".[32] Paul Evdokimov stated: "Hell is nothing else but separation of man from God, his autonomy excluding him from the place where God is present."[33] According to Theodore Stylianopoulos, "Hell is a spiritual state of separation from God and inability to experience the love of God, while being conscious of the ultimate deprivation of it as punishment."[34] Michel Quenot stated: "Hell is none other than the state of separation from God, a condition into which humanity was plunged for having preferred the creature to the Creator. It is the human creature, therefore, and not God, who engenders hell. Created free for the sake of love, man possesses the incredible power to reject this love, to say 'no' to God. By refusing communion with God, he becomes a predator, condemning himself to a spiritual death (hell) more dreadful than the physical death that derives from it."[35] Another writer declared: "The circumstances that rise before us, the problems we encounter, the relationships we form, the choices we make, all ultimately concern our eternal union with or separation from God."[36]

The Eastern Orthodox Church rejects what is presented as the Roman Catholic doctrine of purgatory as a place where believers suffer as their "venial sins" are purged before gaining admittance to heaven.[37]

Contrary to Western Christianity, both Roman and Protestant varieties, the Christians of the East emphasize the mystery of God in his pre-eternal transcendence and maintain a tradition of apophatic theology, while the technical, cataphatic theology of scholasticism tends to be downplayed or viewed as subordinate. Thus, there is no single "official" teaching of the Church apart from apostolic doctrine received and, when necessary, defined by Ecumenical Councils. The Eastern Orthodox positions on hell are derived from the sayings of the saints and the consensus views of the Church Fathers. They are not in agreement on all points, and no council universally recognized by the Eastern Orthodox Churches has formulated doctrine on hell, so there is no official doctrine to which all the faithful are bound. Beliefs concerning the nature and duration of hell are considered theologoumena, or theological opinions, rather than dogmas of the Church.

3.1. Images

Saint John Chrysostom pictured Hell as associated with "unquenchable" fire and "various kinds of torments and torrents of punishment".[38]

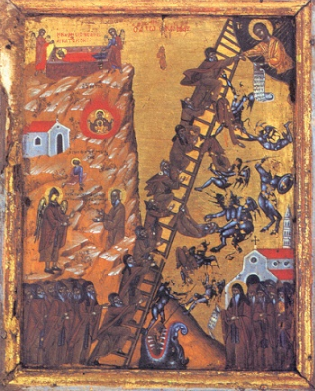

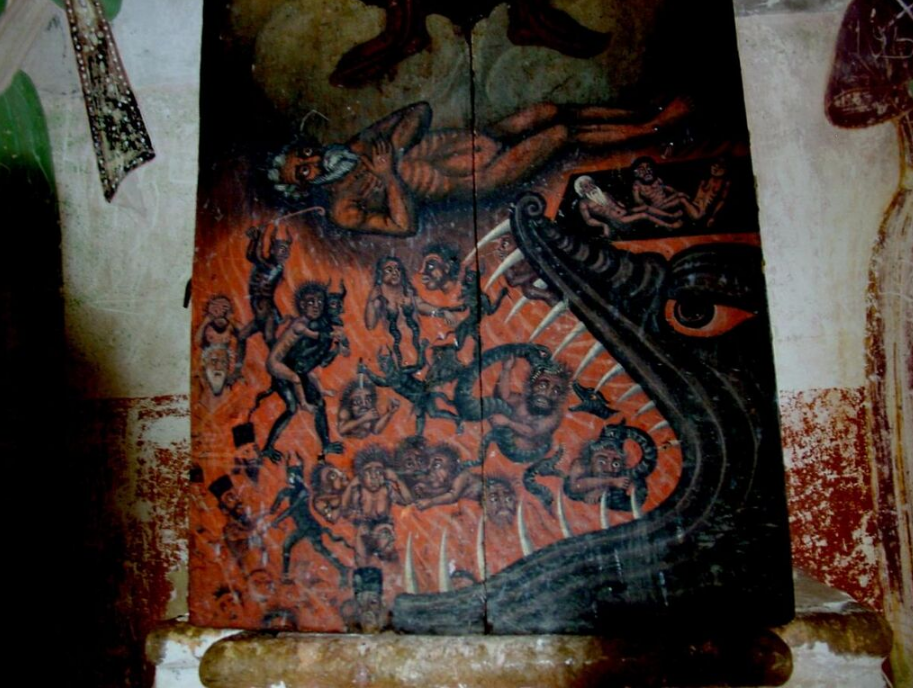

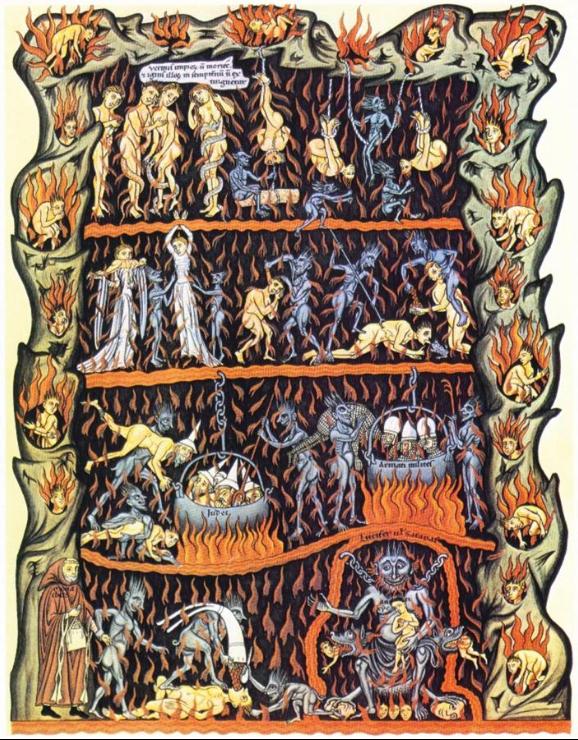

Eastern Orthodox icons of the Last Judgment, most notably in the Slavic traditions, often depict tormented, lost sinners in Hell. Pages 66–69 of John-Paul Himka's Last Judgment Iconography in the Carpathians provides an illustrated description of some such 15th-century Carpathian icons based on a northern Rus' prototype (p. 193). The depiction in these particular icons, a depiction that may have developed from 12th-century Greek and South Slavic depictions differentiating sinners and their punishments (p. 68), is referred to by Himka as "the new hell", "because various sinners are being punished in a squarish area with torments that did not appear in the standard Byzantine iconography" (p. 42).

Icons based on The Ladder of Divine Ascent, by Saint John Climacus, show monks ascending a thirty-rung ladder to Heaven represented by Christ, or succumbing to the arrows of demons and falling from the ladder into Hell, sometimes represented by an open-jawed dragon.[39]

4. Roman Catholicism

4.1. Where Souls Go After Death

Aquinas uses an analogy of buoyancy:

And since a place is assigned to souls in keeping with their reward or punishment, as soon as the soul is set free from the body it is either plunged into hell or soars to heaven, unless it be held back by some debt, for which its flight must needs be delayed until the soul is first of all cleansed. ... Sometimes venial sin, though needing first of all to be cleansed, is an obstacle to the receiving of the reward; the result being that the reward is delayed. [10]

4.2. As Self-Exclusion

The Catechism of the Catholic Church which, when published in 1992, Pope John Paul II declared to be "a sure norm for teaching the faith",[40] defines hell as a freely chosen consequence of refusing to love God:

- We cannot be united with God unless we freely choose to love him. But we cannot love God if we sin gravely against him, against our neighbor or against ourselves: "He who does not love remains in death. Anyone who hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him." Our Lord warns us that we shall be separated from him if we fail to meet the serious needs of the poor and the little ones who are his brethren. To die in mortal sin without repenting and accepting God's merciful love means remaining separated from him for ever by our own free choice. This state of definitive self-exclusion from communion with God and the blessed is called "hell." Jesus often speaks of "Gehenna" of "the unquenchable fire" reserved for those who to the end of their lives refuse to believe and be converted, where both soul and body can be lost. Jesus solemnly proclaims that he "will send his angels, and they will gather... all evil doers, and throw them into the furnace of fire," and that he will pronounce the condemnation: "Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire!" The teaching of the Church affirms the existence of hell and its eternity. Immediately after death the souls of those who die in a state of mortal sin descend into hell, which is described (in quotes) as "eternal fire."[41]

4.3. As a Place or a State

State

The Baltimore Catechism defined Hell by using the word "state" alone: "Hell is a state to which the wicked are condemned, and in which they are deprived of the sight of God for all eternity, and are in dreadful torments." However, suffering is characterized as both mental and physical: "The damned will suffer in both mind and body, because both mind and body had a share in their sins."[42]

Pope John Paul II stated on 28 July 1999, that, in speaking of Hell as a place, the Bible uses "a symbolic language", which "must be correctly interpreted … Rather than a place, hell indicates the state of those who freely and definitively separate themselves from God, the source of all life and joy."[43] Some have interpreted these words as a denial that Hell can be considered to be a place, or at least as providing an alternative picture of Hell.[44] Others have explicitly disagreed with the interpretation of what the Pope said as an actual denial that Hell can be considered a place and have said that the Pope was only directing attention away from what is secondary to the real essence of hell.[45]

Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905–1988) said that "we must see that hell is not an object that is 'full' or 'empty' of human individuals, but a possibility that is not 'created' by God but in any case by the free individuals who choose it".[46]

The Catholic Faith Handbook for Youth, with imprimatur of 2007, also says that "more accurately" heaven and hell are not places but states.[47]

Capuchin theologian Berard A. Marthaler also says that "hell is not 'a place'".[48]

Place

Traditionally in the past Hell has been spoken of or considered as a place.[49] Some have rejected metaphorical interpretations of the biblical descriptions of hell,[50] and have attributed to Hell a location within the earth,[51] while others who uphold the opinion that hell is a definite place, say instead that its location is unknown.[52]

In a homily given on 25 March 2007, Pope Benedict XVI stated: "Jesus came to tell us that he wants us all in heaven and that hell, of which so little is said in our time, exists and is eternal for those who close their hearts to his love."[53][54] Journalist Richard Owen's interpretation of this remark as declaring that hell is an actual place was reported in many media.[55]

Writing in the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, Joseph Hontheim said that "theologians generally accept the opinion that hell is really within the earth. The Catholic Church has decided nothing on this subject; hence we may say hell is a definite place; but where it is, we do not know." He cited the view of Saint Augustine of Hippo that Hell is under the earth and that of Saint Gregory the Great that hell is either on the earth or under it.[56]

The posthumous supplement to Aquinas' Summa theologiciae suppl. Q97 A4 flags discussion of the location of hell as speculation: As Augustine says (De Civ. Dei xv, 16), "I am of opinion that no one knows in what part of the world hell is situated, unless the Spirit of God has revealed this to some one."

Both

Other Catholics neither affirm nor deny that Hell is a place, and speak of it as "a place or state". Ludwig Ott's work "The Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma" said: "Hell is a place or state of eternal punishment inhabited by those rejected by God".[57] Robert J. Fox wrote: "Hell is a place or state of eternal punishment inhabited by those rejected by God because such souls have rejected God's saving grace."[58] Evangelicals Norman L. Geisler and Ralph E. MacKenzie interpret official Roman Catholic teaching as: "Hell is a place or state of eternal punishment inhabited by those rejected by God."[59]

4.4. Nature of Suffering

It is agreed that Hell is a place of suffering.[60][61][62]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

Jesus often speaks of "Gehenna" of "the unquenchable fire" reserved for those who to the end of their lives refuse to believe and be converted, where both soul and body can be lost. Jesus solemnly proclaims that he "will send his angels, and they will gather. . . all evil doers, and throw them into the furnace of fire", and that he will pronounce the condemnation: "Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire!"

The teaching of the Church affirms the existence of hell and its eternity. Immediately after death the souls of those who die in a state of mortal sin descend into hell, where they suffer the punishments of hell, "eternal fire". The chief punishment of hell is eternal separation from God, in whom alone man can possess the life and happiness for which he was created and for which he longs.[63]

Although the Catechism explicitly speaks of the punishments of hell in the plural, calling them "eternal fire", and speaks of eternal separation from God as the "chief" of those punishments, one commentator claims that it is non-committal on the existence of forms of punishment other than that of separation of God: after all, God, being above all a merciful and loving entity, takes no pleasure in the death of the living, and does not will or predestine anyone to go there (the Catholic stance is that God does not will suffering, and that the only entities known to be in hell beyond a doubt are Satan and his evil angels, and that the only suffering in hell is not fire or torture, but the freely-chosen, irrevocable and inescapable eternal separation from God and his freely given love, and the righteous, who are in heaven; thus the Church and the Popes have placed emphasis on the potential irreversibility of a mortally sinful life that goes un-absolved before one's death, and the dogma and reality of the place or state of hell).[64] Another interpretation is that the Catechism by no means denies other forms of suffering, but stresses that the pain of loss is central to the Catholic understanding of hell.[65]

Saint Augustine of Hippo said that the suffering of hell is compounded because God continues to love the sinner who is not able to return the love.[66] According to the Church, whatever is the nature of the sufferings, "they are not imposed by a vindictive judge"[66][67]

"Concerning the detailed specific nature of hell ... the Catholic Church has defined nothing. ... It is useless to speculate about its true nature, and more sensible to confess our ignorance in a question that evidently exceeds human understanding."[68]

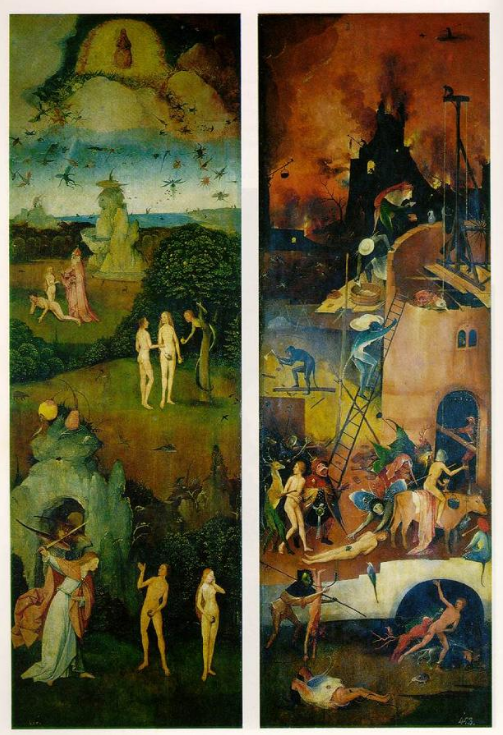

In his book, Inventing Hell, Catholic writer and historian Jon M. Sweeney is critical of the ways that Christians have appropriated Dante's vision and images of hell. In its review, Publishers Weekly called the book "persuasively argued."[69] An article on the same subject by Sweeney that was published on the Huffington Post's religion page was liked by more than 19,000 people, including Anne Rice.[70]

4.5. Visions

A number of Catholic mystics and saints have claimed to have received visions of hell or other revelations concerning hell. During various Marian apparitions, such as those at Fatima or at Kibeho, the visionaries claimed that the Virgin Mary during the course of the visions showed them a view of hell where sinners were suffering.

At Fatima in Portugal, it is claimed that Our Lady told St. Jacinta Marto; that more sinners go to Hell because of sins of impurity more than any other.[71][72]

In the Bible, in the Book of Revelation, John of Patmos writes about seeing a lake of fire where the 'beast' and all those marked with his number were placed.

Columba of Iona is alleged to have on several occasions even been able to name particular individuals who he said were going to end life in hellfire for their sins and accurately predicted the way they would die before the event had even happened.[73]

A story recorded by Cluniac monks in the Middle Ages claimed that St Benedict appeared to a monk on one occasion and told the monk that there had just been (at that point in time) a monk who had fled the monastic life to go back into the world, and the ex-monk then died and he went to hell.[74]

4.6. Call to Responsibility

The Catholic Church teaches that no one is predestined to Hell, and that the Church's teaching on Hell is not meant to frighten but is a call for people to use their freedom wisely. It is first and foremost a call to conversion, and to show that Humanity's true destiny lies with God in heaven.[75]

Predestination

The Catholic Church, and the Catechism, repudiates the view commonly known as "double predestination" which claims that God not only chooses who will be saved, but that he also creates some people who will be doomed to damnation.[76] This view is often associated with the Protestant reformer John Calvin.[75][77]

5. Protestantism

The varying Protestant views of "hell", both in relation to Hades (i.e., the abode of the dead) and Gehenna (i.e., the destination of the wicked), are largely a function of the varying Protestant views on the intermediate state between death and resurrection; and different views on the immortality of the soul or the alternative, the conditional immortality. For example, John Calvin, who believed in conscious existence after death,[78] had a very different concept of hell (Hades and Gehenna) to Martin Luther who held that death was sleep.[79]

In most Protestant traditions, hell is the place created by God for the punishment of the devil and fallen angels (cf. Matthew 25:41), and those whose names are not written in the book of life (cf. Revelation 20:15). It is the final destiny of every person who does not receive salvation, where they will be punished for their sins. People will be consigned to hell after the last judgment.[80]

5.1. Eternal Torment View

One historic Protestant view of hell is expressed in the Westminster Confession (1646):

- "but the wicked, who know not God, and obey not the gospel of Jesus Christ, shall be cast into eternal torments, and punished with everlasting destruction from the presence of the Lord, and from the glory of his power." (Chapter XXXIII, Of the Last Judgment)

According to the Alliance Commission on Unity & Truth among Evangelicals (ACUTE) the majority of Protestants have held that hell will be a place of perpetual conscious torment, both physical and spiritual.[20] This is known as the eternal conscious torment (ECT) view.[81] Some recent writers such as Anglican layman C. S. Lewis[82] and J.P. Moreland[83] have cast hell in terms of "eternal separation" from God. Certain biblical texts have led some theologians to the conclusion that punishment in hell, though eternal and irrevocable, will be proportional to the deeds of each soul (e.g., Matthew 10:15, Luke 12:46-48).[84]

Another area of debate is the fate of the unevangelized (i.e., those who have never had an opportunity to hear the Christian gospel), those who die in infancy, and the mentally disabled. According to ACUTE some Protestants[85] agree with Augustine that people in these categories will be damned to hell for original sin, while others believe that God will make an exception in these cases.[20]

5.2. View of Conditional Immortality and Annihilationism

A minority of Protestants believe in the doctrine of conditional immortality,[86] which teaches that those sent to hell will not experience eternal conscious punishment, but instead will be extinguished or annihilated after a period of "limited conscious punishment".[15][87] A phenomenalist view of immortality[88] holds that there would be no experiential difference between eternal hell and limited conscious punishment.

Prominent evangelical theologians who have adopted conditionalist beliefs include John Wenham, Edward Fudge, Clark Pinnock, Greg Boyd,[89] and John Stott (although the last has described himself as an "agnostic" on the issue of annihilationism).[20] Conditionalists typically reject the traditional concept of the immortality of the soul.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church holds annihilationism. Seventh-day Adventists believe that death is a state of unconscious sleep until the resurrection. They base this belief on biblical texts such as Ecclesiastes 9:5 which states "the dead know nothing", and 1 Thessalonians 4:13 which contains a description of the dead being raised from the grave at the second coming. These verses, Adventists say, indicate that death is only a period or form of slumber.[90]

Jehovah's Witnesses and Christadelphians also teach the annihilationist viewpoint.

6. Other Groups

6.1. Christian Universalism

Though a theological minority in historical and contemporary Christianity, some holding mostly Protestant views (such as George MacDonald, Karl Barth, William Barclay, Keith DeRose and Thomas Talbott) believe that after serving their sentence in Gehenna, all souls are reconciled to God and admitted to heaven, or ways are found at the time of death of drawing all souls to repentance so that no "hellish" suffering is experienced. This view is often called Christian universalism—its conservative branch is more specifically called 'Biblical or Trinitarian universalism'—and is not to be confused with Unitarian Universalism. See universal reconciliation, apocatastasis and the Problem of Hell.

Christian Universalism teaches that an eternal Hell does not exist and is a later creation of the church with no biblical support. Reasoning by Christian Universalists includes that an eternal Hell is against the nature, character and attributes of a loving God, human nature, sin's nature of destruction rather than perpetual misery, the nature of holiness and happiness and the nature and object of punishment.[91]

6.2. Christian Science

Christian Science defines "hell" as follows: "Mortal belief; error; lust; remorse; hatred; revenge; sin; sickness; death; suffering and self-destruction; self-imposed agony; effects of sin; that which 'worketh abomination or maketh a lie.' " (Science and Health with Key to the Scripture by Mary Baker Eddy, 588: 1–4.)

6.3. Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses do not believe in an immortal soul that survives after physical death. They believe the Bible presents "hell", as translated from "Sheol" and "Hades", to be the common grave for both the good and the bad. They reject the idea of a place of literal eternal pain or torment as being inconsistent with God's love and justice. They define "Gehenna" as eternal destruction or the "second death", which is reserved for those with no opportunity of a resurrection such as those who will be destroyed at Armageddon.[92] Jehovah's Witnesses believe that others who have died before Armageddon will be resurrected bodily on earth and then judged during the 1,000-year rule of Christ; the judgement will be based on their obedience to God's laws after their resurrection.[93]

The Christadelphian view is broadly similar to the Jehovah's Witness view, except for the fact that it teaches the belief that the resurrected will be judged for how they lived their lives before the resurrection.

6.4. Latter Day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) teaches that the word "hell" is used scripturally in at least two senses.[94] The first is a place commonly called Spirit Prison which is a state of punishment for those who reject Christ and his Atonement. This is understood to be a temporary state in which the spirits of deceased persons will be taught the gospel and have an opportunity to repent and accept ordinances of salvation.[95] Mormons teach that it was for this purpose that Christ visited the Spirit World after his crucifixion (1 Peter 3:19–20, 1 Peter 4:5–6). Modern-day revelation clarifies that while there, Christ began the work of salvation for the dead by commissioning spirits of the righteous to teach the gospel to those who didn't have the opportunity to receive it while on earth.[95]

Mormons believe that righteous people will rise in a "first resurrection" and live with Christ on earth after His return.[96] After the 1000 years known as the Millennium, the individuals in spirit prison who chose not to accept the gospel and repent[97] will also be resurrected and receive an immortal physical body, which is referred to as the "second resurrection".[98] At these appointed times of resurrection, "death and hell" will deliver up the dead that are in them to be judged according to their works (Revelations 20:13), at which point all but the sons of perdition will receive a degree of glory, which Paul compared to the glory of the sun, moon, and stars (1 Corinthians 15:41). The Church explains biblical descriptions of hell being "eternal" or "endless" punishment as being descriptive of their infliction by God rather than an unending temporal period. Mormon scripture quotes God as telling church founder Joseph Smith: "I am endless, and the punishment which is given from my hand is endless punishment, for Endless is my name. Wherefore—Eternal punishment is God's punishment. Endless punishment is God's punishment."[99] Mormons also believe in a more permanent concept of hell, commonly referred to as outer darkness. It is said that very few people who have lived on the earth will be consigned to this hell, but Mormon scripture suggests that at least Cain will be present.[100] Other mortals who during their lifetime become sons of perdition, those who commit the unpardonable sin, will be consigned to outer darkness.[96] It is taught that the unpardonable sin is committed by those who "den[y] the Son after the Father has revealed him".[101] However, according to Mormon faith, since most humans lack such an extent of religious enlightenment, they cannot commit the Eternal sin,[102] and the vast majority of residents of outer darkness will be the "devil and his angels ... the third part of the hosts of heaven" who in the premortal existence followed Lucifer and never received a mortal body.[103] The residents of outer darkness are the only children of God that will not receive one of three kingdoms of glory at the Last Judgment.

It is unclear whether those in outer darkness will ultimately be redeemed. Of outer darkness and the sons of perdition, Mormon scripture states that "the end thereof, neither the place thereof, nor their torment, no man knows; Neither was it revealed, neither is, neither will be revealed unto man, except to them who are made partakers thereof".[104] The scripture asserts that those who are consigned to this state will be aware of its duration and limitations.

6.5. Swedenborgianism

- See Swedenborgianism § Hell

6.6. Unity Church

The Unity Church of Charles Fillmore considers the concept of everlasting physical Hell to be false doctrine and contradictory to that reported by John the Evangelist.[105]

6.7. Seventh-Day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church believes that the concept of eternal suffering is incompatible with God's character and that He cannot torture His children.[106][107] They instead believe that Hell is not a place of eternal suffering, but of eternal death and that death is a state of unconscious sleep until the resurrection. They base this belief on biblical texts such as Ecclesiastes 9:5 which states "the dead know nothing", and 1 Thessalonians 4:13 which contains a description of the dead being raised from the grave at the second coming. These verses, it is argued, indicate that death is only a period or form of slumber.[90] Based on verses like Matthew 16:27 and Romans 6:23 they believe the unsaved do not go to any place of punishment as soon as they die, but are reserved in the grave until the day of judgment after the Second coming of Jesus to be judged, either for eternal life or eternal death. This interpretation is called annihilationism.

They also hold that Hell is not an eternal place and that the descriptions of it as "eternal" or "unquenchable" does not mean that the fire will never go out. They base this idea in other biblical cases such as the "eternal fire" that was sent as punishment to the people of Sodom and Gomorrah, that later extinguished.[107][108]

7. Biblical Terminology

Sheol

In the King James Bible, the Old Testament term Sheol is translated as "Hell" 31 times,[109] and it is translated as "the grave" 31 times.[110] Sheol is also translated as "the pit" three times.[111]

Modern Bible translations typically render Sheol as "the grave", "the pit", or "death".

Abaddon

The Hebrew word abaddon, meaning "destruction", is sometimes interpreted as being a synonym for "Hell".[112]

Gehenna

In the New Testament, both early (i.e., the KJV) and modern translations often translate Gehenna as "Hell".[113] Young's Literal Translation and the New World Translation are two notable exceptions, both of which simply use the word "Gehenna".

Hades

Hades is the Greek word which is traditionally used in place of the Hebrew word Sheol in works such as the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Like other first-century Jews who were literate in Greek, Christian writers of the New Testament employed this usage. While earlier translations most often translated Hades as "Hell", as does the King James Version, modern translations use the transliteration "Hades",[114] or render the word as allusions "to the grave",[115] "among the dead",[116] "place of the dead"[117] or they contain similar statements. In Latin, Hades were translated as Purgatorium (Purgatory) after about 1200 AD,[118] but no modern English translations render Hades as Purgatory.

Tartarus

Only appears in 2 Peter 2:4 in the New Testament; both early and modern Bible translations usually translate Tartarus as "Hell", though a few render it as "Tartarus".

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Christian_views_on_Hell

References

- "What the Bible says about Death, Afterlife, and the Future" James Tabor https://clas-pages.uncc.edu/james-tabor/ancient-judaism/death-afterlife-future/

- New Bible Dictionary 3rd edition, IVP Leicester 1996. "Sheol".

- Mathews, Robert Trott (1891) (in en). Evangelistic Sermons with an Essay on the Scriptural and Catholic Creed of Baptism. Standard Publishing Company. pp. 225. https://books.google.com/books?id=s8o3AQAAMAAJ&q=In+the+Greek+Septuagint%2C+the+Hebrew+word+Sheol+was+translated+as+Hades&pg=PA225.

- New Bible Dictionary 3rd edition, IVP Leicester 1996, "Hell".

- "Genesis 1:1 (KJV)". https://www.blueletterbible.org/kjv/gen/1/1/s_1001.

- Mt 11:23; 16:18; Lk 10:15; Ac 2:27, 2:31; Rev 1:18; 6:8; 20:13-14. Some late Greek manuscripts, which are followed by KJV and NKJV, have ᾅδης in 1 Cor. 15:55 https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Mt+11%3A23&version=NRSV

- The King James Version translates "ᾅδης" 9 times as "Hell" and once as "grave" (in 1 Cor. 15:55) https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1Cor+15%3A55&version=NRSV

- The 2010 New International Version translates "ᾅδης" seven times as "Hades", and two times as "realm of the dead"; the 1984 NIV translates it four times as "Hades", twice as "depths", twice as "grave", and once as "hell".

- The English Standard Version translates "ᾅδης" 8 times as "Hades" and once as "Hell".

- The Contemporary English Version translates "ᾅδης" twice as "Hell", once as "death", twice as "grave", once as "world of the dead", three times as "death's kingdom".

- The New Living Translation renders "ᾅδης" once as "place of the dead", twice as "the dead" and six times as "the grave".

- Matthew 5:22, 5:29; 5:30;10:28; 18:9; 23:15, 23:33; Mk 9:43, 9:45, 9:47; Lk 12:5; James 3:6. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Mt+10%3A28&version=NRSV

- 2 Peter 2:4 https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=2Peter+2%3A4&version=NRSV

- New Bible Dictionary 3rd ed., IVP, Leicester 1996. Article "Hell", pages 463-464

- New Dictionary of Biblical Theology; IVP Leicester 2000, "Hell"

- Evangelical Alliance Commission on Truth and Unity Among Evangelicals (ACUTE) (2000). The Nature of Hell. Paternoster, London. pp. 42–47.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Luke 12:5-9 - J.B. Phillips New Testament". https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+12%3A5-9&version=PHILLIPS.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Luke 12:5 - Amplified Bible". https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+12%3A5&version=AMP.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Luke 12:5 - Young's Literal Translation". https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+12%3A5&version=YLT.

- Evangelical Alliance Commission on Unity and Truth among Evangelicals (2000). The Nature of Hell. Acute, Paternoster (London).

- "hell." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 4 Mar. 2013.

- God himself is both heaven and hell, reward and punishment. All men have been created to see God unceasingly in his uncreated glory. Whether God will be for each man heaven or hell, reward or punishment, depends on man's response to God's love and on man's transformation from the state of selfish and self-centered love, to Godlike love which does not seek its own ends. "Empirical Theology Versus Speculative Theology" by John S. Romanides part 2 [1]

- Thus it is the Church's spiritual teaching that God does not punish man by some material fire or physical torment. God simply reveals Himself in the risen Lord Jesus in such a glorious way that no man can fail to behold His glory. It is the presence of God's splendid glory and love that is the scourge of those who reject its radiant power and light. ... those who find themselves in hell will be chastised by the scourge of love. How cruel and bitter this torment of love will be! For those who understand that they have sinned against love, undergo no greater suffering than those produced by the most fearful tortures. The sorrow which takes hold of the heart, which has sinned against love, is more piercing than any other pain. It is not right to say that the sinners in hell are deprived of the love of God ... But love acts in two ways, as suffering of the reproved, and as joy in the blessed! (St. Isaac of Syria, Mystic Treatises) The Orthodox Church of America website [2]

- For those who love the Lord, his Presence will be infinite joy, paradise and eternal life. For those who hate the Lord, the same Presence will be infinite torture, hell and eternal death. The reality for both the saved and the damned will be exactly the same when Christ "comes in glory, and all angels with Him, " so that "God may be all in all." (I Corinthians 15-28) Those who have God as their "all" within this life will finally have divine fulfillment and life. For those whose "all" is themselves and this world, the "all" of God will be their torture, their punishment and their death. And theirs will be "weeping and gnashing of teeth." (Matthew 8:21, et al.) The Son of Man will send His angels and they will gather out of His kingdom all causes of sin and all evil doers, and throw them into the furnace of fire; there men will weep and gnash their teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the Kingdom of their Father. (Matthew 13:41-43) According to the saints, the "fire" that will consume sinners at the coming of the Kingdom of God is the same "fire" that will shine with splendor in the saints. It is the "fire" of God's love; the "fire" of God himself who is love. "For our God is a consuming fire" (Hebrews 12:29) who "dwells in unapproachable light." (I Timothy 6:16) For those who love God and who love all creation in him, the "consuming fire" of God will be radiant bliss and unspeakable delight. For those who do not love God, and who do not love at all, this same "consuming fire" will be the cause of their "weeping" and their "gnashing of teeth." Thus it is the Catholic Church's spiritual teaching that God does not punish man by some material fire or physical torment. God simply reveals himself in the risen Lord Jesus in such a glorious way that no man can fail to behold his glory. It is the presence of God's splendid glory and love that is the scourge of those who reject its radiant power and light. ... those who find themselves in hell will be chastised by the scourge of love. How cruel and bitter this torment of love will be! For those who understand that they have sinned against love, undergo no greater suffering than those produced by the most fearful tortures. The sorrow which takes hold of the heart, which has sinned against love, is more piercing than any other pain. It is not right to say that the sinners in hell are deprived of the love of God ... But love acts in two ways, as suffering of the reproved, and as joy in the blessed! (St. Isaac of Syria, Mystic Treatises) The Orthodox Church of America website [3]

- "Paradise and Hell exist not in the form of a threat and a punishment on the part of God but in the form of an illness and a cure. Those who are cured and those who are purified experience the illuminating energy of divine grace, while the uncured and ill experience the caustic energy of God." [4]

- Man has a malfunctioning or non-functioning noetic faculty in the heart, and it is the task especially of the clergy to apply the cure of unceasing memory of God, otherwise called unceasing prayer or illumination. "Those who have selfless love and are friends of God see God in light—Divine light, while the selfish and impure see God the judge as fire—darkness". [5]

- "Those who have selfless love and are friends of God see God in light—divine light, while the selfish and impure see God the judge as fire—darkness". [6]

- Proper preparation for vision of God takes place in two stages: purification, and illumination of the noetic faculty. Without this, it is impossible for man's selfish love to be transformed into selfless love. This transformation takes place during the higher level of the stage of illumination called theoria, literally meaning vision-in this case vision by means of unceasing and uninterrupted memory of God. Those who remain selfish and self-centered with a hardened heart, closed to God's love, will not see the glory of God in this life. However, they will see God's glory eventually, but as an eternal and consuming fire and outer darkness. From FRANKS, ROMANS, FEUDALISM, AND DOCTRINE/Diagnosis and Therapy Father John S. Romanides Diagnosis and Therapy [7]

- http://www.fordham.edu/academics/programs_at_fordham_/theology/faculty/aristotle_papanikola_26156.asp

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110202043637/http://www.bu.edu/ir/faculty/alphabetical/prodromou/

- Regarding specific conditions of after-life existence and eschatology, Orthodox thinkers are generally reticent; yet two basic shared teachings can be singled out. First, they widely hold that immediately following a human being's physical death, his or her surviving spiritual dimension experiences a foretaste of either heaven or hell. (Those theological symbols, heaven and hell, are not crudely understood as spatial destinations but rather refer to the experience of God's presence according to two different modes.) Thinking Through Faith: New Perspectives from Orthodox Christian Scholars page 195 By Aristotle Papanikolaou, Elizabeth H. Prodromou [8]

- Sophrony, Archimandrite (2001). The Monk of Mount Athos: Staretz Silouan, 1866-1938. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-913836-15-X. https://books.google.com/books?id=JERJcdSKDbsC&pg=PA32.

- In the World, of the Church: A Paul Evdokimov Reader. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. 2001. p. 32. ISBN 0-88141-215-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=-6yosWlACnYC&pg=PA32.

- Father Theodore Stylianopoulos http://stgeorgekeene.pmcgee.org/monthlybulletins/August2010bulletin.pdf

- Quenot, Michel (1997). The Resurrection and the Icon. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-88141-149-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=YppZakl7uygC&pg=PA85.

- "The Spirit of Thankfulness". http://www.theologic.com/oflweb/secular/thank3.htm.

- Orthodox Christianity also rejects such teachings as the Immaculate Conception, purgatory, and other uniquely Roman Catholic doctrines. [9]

- Epistle I to Theodore of Mopsuestia http://www.monachos.net/content/patristics/patristictexts/171-chrysostom-theodore

- Cormack, Robin (2007). Icons. British Museum Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-674-02619-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=hsAApqqC1KUC&pg=PA20.

- "Fidei depositum". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 11 October 1992. https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_constitutions/documents/hf_jp-ii_apc_19921011_fidei-depositum_en.html.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1033 https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P2O.HTM

- "Lesson 37: On the Last Judgment and the Resurrection, Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven". https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/resources/catechism/baltimore-catechism/lesson-37-on-the-last-judgment-and-the-resurrection-hell-purgatory-and-heaven.

- "28 July 1999 - John Paul II". https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/1999/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_28071999.html.

- "Hell is traditionally considered a literal place of eternal torture, but the Pope has also described hell as the condition of pain that results from alienation from God, a thing of one's own doing, not an actual place.", Burke, Chauvin, & Miranti, Religious and spiritual issues in counseling, p. 236 (2003).

- "In the common sense of the word 'place', if you were to say 'Hell is not a place', you would be denying that Hell exists. Some thought that the Pope, in the statement quoted above, was denying that Hell is a place in this sense. He was, of course, doing nothing of the sort. Thus, to return to the Pope's words again, John Paul II must not be misinterpreted when he said 'Rather than [or more than] a place, hell indicates [a] state….' He certainly was not denying that it is a place, but instead was shifting our focus to the real essence of hell—what the term 'hell' truly indicates—the self-chosen separation from God. The 'place' or 'location' of hell is secondary, and considerations of where it is should not deflect us from our most important concerns: what it is, and how to avoid it" (https://web.archive.org/web/20110928085437/http://www.cuf.org/faithfacts/details_view.asp?ffID=69%29.

- Jack Mulder (2010). Kierkegaard and the Catholic Tradition. Indiana University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-253-22236-7. https://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&q=mulder+%22free+individuals+who%22&btnG=.

- Singer-Towns, Brian; Claussen, Janet; Vanbrandwijk, Clare (2008). Catholic Faith Handbook for Youth. Saint Mary's Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-88489-987-7. https://archive.org/details/catholicfaithhan00sing.

- Marthaler, Berard A. (2007). The Creed. Twenty-Third Publications. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-89622-537-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=TY3-aZIo9HEC&pg=PA211.

- Flatt, Lizann (2009). Religion in the Renaissance. Crabtree. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7787-4597-6. https://archive.org/details/religioninrenais0000flat. "Hell was a place of eternal suffering for sinners"

- "No cogent reason has been advanced for accepting a metaphorical interpretation in preference to the most natural meaning of the words of Scripture" (Hontheim in Catholic Encyclopedia 1910).

- "Theologians generally accept the opinion that hell is really within the earth" (Hontheim 1910)

- "It is certain from Scripture and tradition that the torments of hell are inflicted in a definite place. But it is uncertain where the place is" Addis & Arnold (eds), A Catholic Dictionary Containing Some Account of the Doctrine, Discipline, Rites, Ceremonies, Councils, and Religious Orders of the Catholic Church: Part One, p. 404 (1903).

- "25 March 2007: Pastoral visit to the Parish of "Santa Felicita e Figli martiri", Rome - BENEDICT XVI". https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20070325_visita-parrocchia.html.

- CiNews of 28 March 2007 http://www.cinews.ie/article.php?artid=3356

- The Times, 27 March 2007, reported "Hell is a place where sinners really do burn in an everlasting fire, and not just a religious symbol designed to galvanise the faithful, the Pope has said" (The Fires of Hell Are Real and Eternal, Pope Warns). Fox News reproduced the article as published on The Times, under the heading: "Pope: Hell Is a Real Place Where Sinners Burn in Everlasting Fire" (Pope: Hell Is a Real Place Where Sinners Burn in Everlasting Fire ). The Australian published Owen's article on its 28 March 2007 issue (Hell is real and eternal: Pope). The Canadian National Post of 28 March 2007, quoting The Times, reported: "Pope Benedict XVI has been reminding the faithful of some key beliefs of their faith, including the fact hell is a place where sinners burn in an everlasting fire" (Hell 'exists and is eternal, ' Pope warns ). The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of 3 April 2007, again referring to The Times, reported: "Pope Benedict XVI has reinstated hell as a real place where the heat is always on." (Playing with fire) http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article1572646.ece

- Joseph Hontheim, "Hell" in The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. Retrieved 3 September 2010 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07207a.htm

- Ott, The Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, p. 479 (1955).

- Fox, "The Catholic Faith", p. 262 (1983).

- Geisler & MacKenzie, "Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: agreements and differences", p. 143 (1995).

- "The Green Catechism" (1939–62) said: Hell is a place of torments. God made hell to punish the devils or bad angels, and all who die in mortal sin. No one can come out of Hell, for out of Hell there is no redemption" (Crawford & Rossiter, "Reasons for Living: Education and Young People's Search for Meaning" (2006). p. 192).

- "Hell is the place and state of eternal punishment for the fallen angels and human beings who die deliberately estranged from the love of God" (work by Fr. Kenneth Baker published by Ignatius Press ).

- "What do we mean by "hell"? Hell is the place and state of eternal punishment for the fallen angels and human beings who die deliberately estranged from the love of God. The existence of hell, as the everlasting abode of the devils and those human beings who have died in the state of mortal sin, is a defined dogma of the Catholic Church" (Baker, "Fundamentals of Catholicism" (1983), volume 3, p. 371).

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1035 https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P2O.HTM

- "The recent Catechism is ambiguous, neither denying nor confirming the existence of physical torments" - Charles Steven Seymour, "A Theodicy of Hell', p. 82 (2000).

- "Hell is the natural consequence of a life lived apart from God. The terrible suffering of hell consists in the realization that, over the course of a lifetime, one has come, not to love, but to hate one's true good, and thus to be radically unfit to enjoy that Good. It is this pain of loss that is central to the Catholic understanding of hell. Imagine the predicament of one who both knows that God is the great love of his life, and that he has turned irreversably away from this love. This is what hell is" (J. A. DiNoia, Gabriel O'Donnell, Romanus Cessario, Peter J. Cameron (editors), The Love That Never Ends: A Key to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, p. 45). https://books.google.com/books?id=FwP7UTl2zWoC&pg=PA45&dq=catholic+hell+suffering&hl=en&ei=DtdATrvaD86WhQfR3f2_CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCsQ6AEwADgo#v=onepage&q=catholic%20hell%20suffering&f=false

- Marthaler, Berard L. (2007). The Creed. Twenty-Third Publications. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-89622-537-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=TY3-aZIo9HEC&pg=PA211.

- Hayes, Zachary J. (1996). Four Views on Hell. Zondervan. p. 176. ISBN 0-310-21268-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=aqwXZMeuJkoC&pg=PA176.

- John Anthony O'Brien, The Faith of Millions: The Credentials of the Catholic Religion, pp. 19–20 https://books.google.com/books?id=O-kj_LncEjAC&pg=PA19&dq=catholic+hell+suffering&hl=en&ei=DtdATrvaD86WhQfR3f2_CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CEcQ6AEwBTgo#v=onepage&q=catholic%20hell%20suffering&f=false

- "Nonfiction Book Review: Inventing Hell: Dante, the Bible, and Eternal Torment by Jon M. Sweeney. Jericho, $16 trade paper (208p) ISBN 978-1-4555-8224-2". https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-4555-8224-2.

- "Anne Rice". https://www.facebook.com/annericefanpage/posts/10152502099210452.

- "A Summary of the Message of Fatima". http://www.salvemariaregina.info/Message.html.

- "Week 1 - Lent with Jacinta - The "sins of impurity"" (in en). 2019-03-07. https://www.bluearmy.com/week-1-lent-with-jacinta-the-sins-of-impurity/.

- Adomnan of Iona, Life of St Columba. Penguin Books, 1995

- Lucy Margaret Smith. The Early History of the Monastery of Cluny. Oxford University Press, 1920

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – Hell". https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P2O.HTM.

- Bayer, Oswald (2008). Martin Luther's Theology: A Contemporary Interpretation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 209. ISBN 9780802827999. https://books.google.com/books?id=52K_z0ZJ1IsC&q=Double+predestination&pg=PA209.

- James, Frank A., III (1998). Peter Martyr Vermigli and Predestination: The Augustinian Inheritance of an Italian Reformer. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 30, 69.

- Calvin Psychopannychia

- Luther Exposition of Salomon's Booke etc.

- Bruce Milne (1998). Know the Truth, 2nd ed.. IVP. p. 335.

- Date, Christopher; Highfield, Ron (13 October 2015) (in en). A Consuming Passion: Essays on Hell and Immortality in Honor of Edward Fudge. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4982-2306-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=xGOPCwAAQBAJ&q=eternal+conscious+torment+ect&pg=PA84.

- C. S. Lewis, The Great Divorce, 1946

- Lee Strobel, The Case for Faith, 2000

- Millard Erickson (2001). Introducing Christian Doctrine, 2nd ed. Baker Academic.

- K. P. Yohannan, Revolution in World Missions, 1986-2004, chapter 10: "I ask my listeners to hold their wrists and find their pulse. Then I explain that every beat they feel represents the death of someone in Asia who has died and gone to eternal hell without ever hearing the Good News of Jesus Christ even once."

- The Nature of Hell. Conclusions and Recommendations. Evangelical Alliance. 2000. http://www.eauk.org/theology/acute/loader.cfm?csModule=security/getfile&pageid=9164. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Solving the Problem of Hell - Afterlife". 23 July 2011. https://www.afterlife.co.nz/2011/07/problem-of-hell/.

- Hell: A Thought Experiment. 28 September 2020. http://www.philosophical-investigations.org/2020/09/hell-thought-experiment.html.

- "Are you an annihilationist, and if so, why?". 19 January 2008. https://reknew.org/2008/01/are-you-an-annihilationist-and-if-so-why/.

- "What do Seventh Day Adventists Really Believe?". https://www.adventist.org/en/beliefs/.

- Guild, E.E. 'Arguments in Favour of Universalism'. http://www.tentmaker.org/books/InFavorCh20.html http://godfire.net/eby/saviour_of_the_world.html http://www.godfire.net/Hellidx.html

- "What Really Is Hell?". The Watchtower: 5–7. July 15, 2002. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/2002521.

- "What Is Judgment Day?". Awake!: 10–11. January 2010. http://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/102010006.

- ""Hell", True to the Faith: A Gospel Reference (Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church, 2004) p. 81. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/true-to-the-faith/hell

- Doctrine and Covenants section 138. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/138?lang=eng

- "Chapter 46: The Last Judgment", Gospel Principles (Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church, 2011). https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-principles/chapter-46-the-final-judgment

- "Hell". https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/gs/hell?lang=eng.

- Doctrine and Covenants 88:100–01. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/88.100-101?lang=eng

- Doctrine and Covenants 19:10–12. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/19.10,12?lang=eng

- Moses 5:22–26. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/pgp/moses/5.22-26?lang=eng

- LDS Church, Guide to the Scriptures: Hell; see also Doctrine and Covenants 76:43–46. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/gs/hell

- Spencer W. Kimball: The Miracle of Forgivness, p. 123.

- Doctrine and Covenants 29:36–39. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/29.36-39?lang=eng

- Doctrine and Covenants 76:45–46. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/76.45-46?lang=eng

- "The word Hell is not translated with clearness sufficient to represent the various meanings of the word in the original language. There are three words from which "Hell" is derived: Sheol, "the unseen state"; Hades, "the unseen world"; and Gehenna, "Valley of Hinnom." These are used in various relations, nearly all of them allegorical. In a sermon Archdeacon Farrar said: "There would be the proper teaching about Hell if we calmly and deliberately erased from our English Bibles the three words, 'damnation, ' 'Hell, ' and 'everlasting. ' I say—unhesitatingly I say, claiming the fullest right to speak with the authority of knowledge—that not one of those words ought to stand any longer in our English Bible, for, in our present acceptation of them, they are simply mistranslations." This corroborates the metaphysical interpretation of Scripture, and sustains the truth that Hell is a figure of speech that represents a corrective state of mind. When error has reached its limit, the retroactive law asserts itself, and judgment, being part of that law, brings the penalty upon the transgressor. This penalty is not punishment, but discipline, and if the transgressor is truly repentant and obedient, he is forgiven in Truth. —Charles Fillmore, Christian Healing, Lesson 11, item eleven."

- "Forever and Ever". https://www.adventistreview.org/forever-and-ever.

- https://www.bibleinfo.com/en/questions/how-long-does-hell-burn

- Jude 1:7 https://www.biblica.com/bible/?osis=niv:Jude%201:7

- Deut. 32:22, Deut. 32:36a & 39, II Sam. 22:6, Job 11:8, Job 26:6, Psalm 9:17, Psalm 16:10, Psalm 18:5, Psalm 55:15, Psalm 86:13, Ps. 116:3, Psalm 139:8, Prov. 5:5, Prov. 7:27, Prov. 9:18, Prov. 15:11, Prov. 15:24, Prov. 23:14, Prov. 27:20, Isa. 5:14, Isa. 14:9, Isa. 14:15, Isa. 28:15, Isa. 28:18, Isa. 57:9, Ezek. 31:16, Ezek. 31:17, Ezek. 32:21, Ezk. 32:27, Amos 9:2, Jonah 2:2, Hab. 2:5

- Gen. 37:35, Gen. 42:38, Gen. 44:29, Gen. 44:31, I Sam. 2:6, I Kings 2:6, I Kings 2:9, Job 7:9, Job 14:13, Job 17:13, Job 21:13, Job 24:19, Psalm 6:5, Psalm 30:3, Psalm 31:17, Psalm 49:14, Psalm 49:14, Psalm 49:15, Psalm 88:3, Psalm 89:48, Prov. 1:12, Prov. 30:16, Ecc. 9:10, Song 8:6, Isa. 14:11, Isa. 38:10, Isa. 38:18, Ezek. 31:15, Hosea 13:14, Hosea 13:14, Psalm 141:7

- Num. 16:30, Num. 16:33, Job 17:16

- Roget's Thesaurus, VI. V.2, "Hell"

- Mat. 5:29, Mat. 5:30, Matt. 10:28, Matt. 23:15, Matt. 23:33, Mark 9:43, Mark 9:45, Mark 9:47, Luke 12:5, Matt. 5:22, Matt. 18:9, Jas. 3:6

- Acts 2:27, New American Standard Bible

- Acts 2:27, New International Version

- Acts 2:27, New Living Translation

- Luke 16:23, New Living Translation

- Catholic for a Reason, edited by Scott Hahn and Leon Suprenant, copyright 1998 by Emmaus Road Publishing, Inc., chapter by Curtis Martin, pg 294-295