Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent gynecological disease that manifests as endometrial tissue that occurs outside of its original location, i.e., in the uterus’s muscular layer, other genitals and their surroundings, or even in locations outside of the body’s genital organs [

1]. Endometrial foci can develop outside of the uterus in places including the peritoneum, the bladder, the ureters, or the ovaries [

2]. Functionally, the ectopic endometrial tissue is similar to the eutopic endometrium. Ovarian cysts, peritoneal endometriosis, and nodules of deeply infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) in the vaginal-rectal septum or the gut are the three most common kinds of endometriosis [

3]. The specific etiology of endometriosis has not yet been determined. Congenital, allergic, epigenetic, environmental, and autoimmune are some of the etiological factors that are listed [

4].

One very typical symptom of endometriosis is infertility. Infertility can affect approximately 35–50% of women who suffer from endometriosis [

5]. Up to 50% of women with pelvic pain and/or infertility and 10–15% of reproductive-aged women have endometriosis [

6]. Endometriosis symptoms include infertility, dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, mittelschmerz, back pain, dysuria, dyschezia, abundant irregular menstruation, gastrointestinal problems (diarrhea or constipation), hematochezia, and chronic fatigue [

7,

8,

9]. Adhesions, organ damage, and fibrosis are the main causes of infertility and pain in endometriosis’ severe phases [

10]. Endometriosis can have an impact on a woman’s general health as well as her mental and social well-being [

11,

12,

13]. The quality of life is significantly reduced as a result [

11,

14].

Endometriosis is a disorder that is highly underdiagnosed and undertreated, with a long lag time of 8–12 years between the symptom onset and a definitive diagnosis [

15,

16]. Since most symptoms are non-specific, there are currently no non-invasive diagnostic techniques that can accurately identify a problem that can definitively diagnose a condition [

17]. However, a thorough medical history, a gynecological examination using a speculum, a bimanual pelvic examination, imaging techniques [

16], ultrasonography [

18], three- and four-dimensional transperineal ultrasound [

19], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)), and biochemical tests are beneficial in the early diagnosis of the disease [

4,

20].

2. MicroRNAs as a New Diagnostic Biomarker for Endometriosis

miRNAs are evolutionary conserved, non-coding, regulatory RNA molecules with 21–25 nucleotides (nt) in length that target 3´-untranslated region (3´-UTR) of specific mRNAs and promote mRNA degradation and suppress translation [

38,

39,

40,

41]. MicroRNAs participate in RNA silencing and regulation of gene expression post-transcriptionally [

39,

40]. It is estimated that about 2588 miRNAs regulate the expression of over 60% of all genes in humans [

42]. MicroRNAs play vital roles in a wide variety of physiological and pathological processes including, cell-to-cell signalling, cell division, apoptosis, proliferation, cell differentiation, and stress response. The aberrant expression of miRNAs is associated with the pathogenesis and progression of numerous diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular, inflammatory, and gynecological conditions [

38,

39,

43]. A systemic review assessed that several studies have focused on the precise regulation of gene expression by miRNAs [

44]. The regulation of gene expression by miRNA has occurred through a fine-tuned and complex network in which a single miRNA modulates over a hundred mRNAs and each transcript might be targeted by several miRNAs [

40,

44,

45].

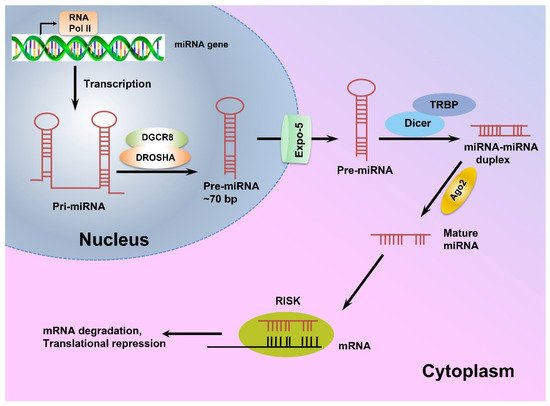

miRNA genes are mostly located within the intronic regions of protein-coding genes and transcribed as long primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) by RNA polymerase II (RNA PolII) [

45,

46]. The pri-miRNAs are then processed in the nucleus by Drosha endonuclease and its cofactor DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region 8 (DGCR8), and cleaved into precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNA) [

46,

47]. Next, exportin-5 transports pre-miRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where they are processed by RNase III Dicer to produce 21–24 nt long double-stranded-miRNAs, which are then unwound to single-stranded molecules by helicases [

45,

46,

48]. The mature single-stranded miRNAs are subsequently assembled into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and target mRNAs with complementary sequences to regulate gene expression post-translationally [

45]. A schematic view of miRNA biogenesis is depicted in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. The schematic view of miRNA biogenesis.

MicroRNAs are mainly transcribed by RNA polymerase II as long pri-miRNAs, which are then processed in the nucleus by Drosha endonuclease and its cofactor DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region 8 (DGCR8). Next, exportin-5 transports the resulting pre-miRNA to the cytoplasm where a complex of Dicer enzyme and TAR RNA binding protein (TRBP) creates a double-stranded miRNA which is unwound to a mature single-stranded miRNA. Finally, the single-stranded miRNA is assembled into a miRNA-induced silencing effector complex (RISC), leading to complementary mRNA sequence and regulating gene expression post-translationally [

45,

49].

Furthermore, miRNAs can be released from cells into the circulation and other biological fluids such as urine, saliva, spinal fluid, follicular fluid, and menstrual blood via a variety of carriers, including exosomes, which confer significant stability against ribonucleases (RNAses) [

44]. Circulating miRNAs serve as messengers. They are delivered to distant cells by exosomes so that they can modulate the translation in the recipient cells [

35,

44]. The biogenesis and expression of miRNAs are tightly regulated and alteration in miRNA expression has been observed in many diseases, implying that aberrant miRNAs expression is associated with some alteration in healthy physiological conditions and leads to diseases such as gynecological conditions [

39,

44]. Different studies have linked the dysregulation of miRNA expression to the pathogenesis of endometriosis [

40,

41,

50].

In 2009, Ohlsson et al. carried out a miRNA microarray analysis to determine the miRNA expression profile of ectopic endometrial lesions and eutopic endometrium tissues obtained from endometriosis-afflicted women. They found that 22 miRNAs were expressed differently in ectopic and eutopic endometrial tissue samples, with 14 miRNAs being upregulated and eight miRNAs being downregulated [

51].

Some dysregulated miRNAs have been proposed to modulate the genes that are implicated in the processes necessary for endometriosis development and progression, like inflammation, angiogenesis, and immunological modulations [

41,

50].

Braza-Boils et al. (2014) identified the endometriosis-related miRNA expression profiles in endometrial tissues and endometriotic lesions taken from the same patients. They also looked at the relationship between the miRNA expression levels and some important angiogenic and fibrinolytic factors in endometrial tissues and three types of endometriotic lesions [

50]. According to their findings, miR-202-3p, miR-424-5p, miR-449b-3p, and miR-556-3p were significantly downregulated, and VEGF-A and uPA were upregulated in patient endometrial tissue compared to the healthy endometrium. They also noticed that miR-449b-3p was significantly downregulated in ovarian endometrioma compared to endometrium removed from both patients and controls, while PAI-1 and the angiogenic inhibitor TSP-1 were both upregulated. Additionally, they found that miR-424-5p expression was inversely correlated with the protein levels of VEGF-A in patient endometrial tissue and miR-449b-3p expression was inversely correlated with the protein levels of TSP-1 in ovarian endometrioma [

50].

Gao et al. in 2019, used quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to determine the expression levels of mir-451 in cultured primary cells, obtained from ectopic and eutopic endometrial tissues, pathologic tissues of endometriosis patients, and healthy women. MiR-451 expression was shown to be decreased in eutopic endometrial tissues taken from endometriosis patients compared with the control. Furthermore, they observed that overexpression of miR-451 induced apoptosis and hindered cell proliferation in cultured eutopic cells whereas siRNA-mediated miR-451 knockdown reversed these effects [

52].

Aberrant expression of miRNAs has also been well documented in the circulation and other body fluids of endometriosis patients, suggesting that these molecules can serve as beneficial diagnostic biomarkers for the non-invasive and early detection of endometriosis, leading to earlier medical interventions [

39,

41,

48,

53,

54]. However, the issues arose as a result of inconsistencies or divergences in the findings [

41]. Different studies have introduced different sets of miRNAs with different expression patterns as potential biomarkers of endometriosis. At present, there is no validated miRNA-base diagnosis test for the non-invasive detection of endometriosis. However, the potential use of circulating miRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers for endometriosis has been considered as an ongoing research area and its diagnostic and therapeutic implications are being extensively studied [

39,

41,

43,

55,

56].

In 2013, Wang et al. performed a circulating miRNA array analysis and identified different miRNA expression patterns in the serum of the endometriosis patients compared with the control [

57]. They reported that the relative expression levels of miR-122 and miR-199a in serum samples from endometriosis patients were higher than the control, while the expression levels of some other miRNAs such as miR-145*, miR-141*, miR-542-3p, and miR-9* were lower [

57]. In the case of the miR-9*, the same result was reported by Nisenblat et al. [

35] in 2019.

Jia et al. (2013) performed a miRNA microarray analysis and demonstrated that plasma levels of miR-17-5p, miR-20a, and miR-22 were downregulated in endometriosis patients [

56]. In another study, Bashti et al. collected plasma samples from women with or without endometriosis and analyzed them using the qRT-PCR technique to compare the expression levels of miR-145 and miR-31. They found that miR-31 was downregulated while miR-145 was upregulated significantly in women with endometriosis [

58]. In addition, altered serum levels of let-7b, let-7d, and let-7f during the proliferative phase were suggested as a diagnostic marker for endometriosis [

43]. Furthermore, plasma levels of miR-200a and miR-141 were lower in endometriosis patients, suggesting them as potential novel noninvasive biomarkers for endometriosis [

40,

54]. It is worth noting that evaluating two or more biomarkers at the same time increases the prognostic value [

40]. Vanhi et al. [

41] conducted a genome-wide miRNA expression profiling to determine a group of plasma miRNAs that can distinguish between endometriosis and non-endometriosis patients. They identified 42 miRNAs, but only one panel comprising hsa-miR-125b-5p, hsa-miR-28-5p, and hsa-miR-29a-3p with intermediate sensitivity (78%) but low specificity (37%), showed diagnostic power.

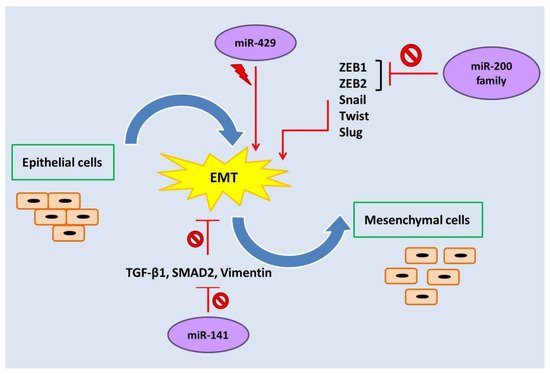

3. The Role of miR-200 Family Members in Endometriosis

The miR-200 family of miRNAs consists of five evolutionary conserved members, namely, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-429, miR-200c, and miR-141, which are encoded in two clusters of hairpin precursors on human chromosomes 1 (miR-200b/a and miR-429) and 12 (miR-200c and miR-141) [

65]. These miRNAs not only play roles in tumor development, angiogenesis, and metastasis, but they also regulate some vital biological processes such as cellular transformation, cell proliferation, drug resistance, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (

Figure 2) [

49,

54,

66].

Figure 2. The miR-200 family regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

: Inhibition,

: Stimulation.

: Inhibition,

: Inhibition,  : Stimulation.

: Stimulation.