There is ample evidence supporting a key role of sleep in memory consolidation. Thalamo-cortical and hippocampal-neocortical interactions allow the reconfiguration of synapses. Oscillatory and molecular changes are involved during sleep in memory consolidation and synaptic rescalling.

- sleep

- memory

- NREM

- REM

- SWS

- slow waves

- theta

- spindles

- hippocampus

1. Introduction

Declarative memory is hippocampal-dependent both in early stages of memory consolidation and also in recall [1] and after consolidation occurs, memories become hippocampal-independent [2]. Specifically in Alzheimer's disease (AD), declarative episodic memory is affected in the early stages, while other types of memory only deteriorate as the disease progresses [3][4][5][6][7].

2. Role of Sleep in Declarative Memory Consolidation

The active systems consolidation hypothesis is currently one of the most important theories on the mechanisms of declarative memory consolidation. It focuses on the interaction between neocortex and hippocampus during sleep. After encoding, memories are labile and highly dependent on the hippocampus. To create more stable long-term memories, the hippocampal representations are repeatedly reactivated during sleep. These reactivations coactivate neocortical areas that will integrate the new representations into preexisting memories [8].

Ample evidence pointed out a key role of sleep in declarative memory consolidation. Animal and human studies supported three main evidences: firstly, the amount of sleep—or the amount of a specific sleep stage—increased following learning or environmental enrichment, with a consequent increase in hippocampal and cortical plasticity. Secondly, sleep—or certain sleep stages—improved performance in certain memory and learning tasks. Finally, sleep deprivation impaired cognitive processing in different ways and, in healthy humans, it decreased the ability to induce long term potentiation (LTP) plasticity [9][10].

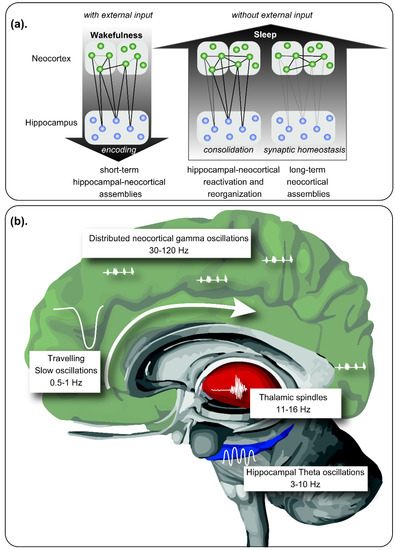

Sleep in mammals consists of a cyclic alternation between Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and Non-REM (NREM) sleep. REM sleep was characterized by a theta activity (4–8 Hz) that appear especially in the hippocampus, coupled to a gamma activity (30–120 Hz). NREM sleep is divided into light (N1 and N2) and deep sleep (N3, also called slow wave sleep—SWS). During the N2 stage of NREM sleep, there is a characteristic thalamo-cortical reactivation that displays sudden bursts of oscillatory brain activity between 12–15 Hz called sleep spindles. N3 NREM sleep is characterized by slow waves between 1–4 Hz and by slow oscillations (SO) of <1 Hz, which represent the slow wave activity (SWA) [11]. During this stage an interplay between the hippocampus and neocortex occurs [12]. Finally, in N3 NREM also appears hippocampal sharp-wave/ripples, which are intermittent patterns of highly synchronous spiking seen as high-frequency oscillations (120–200 Hz) [13][14][15]. It represents the reactivation of hippocampal memory representations and has been proposed as a cognitive biomarker for episodic memory [16]. Sleep spindles also occur during N3 sleep where their occurrence is often obscured by slow oscillations [17] (see Figure 1 for summarizing).

The interaction and the timing of these oscillations during NREM sleep will be critical for a correct communication between the hippocampus, neocortex and other structures. A precise timing will allow thalamic spindles to couple with the correct SO phase. The specific SO-spindle coupling will then facilitate synaptic plasticity and enhance consolidation, while a mistimed coupling will diminish memory formation. At the same time, hippocampal sharp-waves/ripples need to be timed to spindles, which will result in a spindle-ripple coupling. Therefore, the correct timing and characteristics of these waves will allow the reactivated hippocampal information (ripples) to be transmitted to the neocortex (SO), by way of the thalamus (spindles). This process will facilitate synaptic consolidations processes that will store the information as a long-term memory [18].

Finally, REM sleep is thought to process specifically emotional memories, given that it presents a distribution of theta activity within limbic structures. Furthermore, REM sleep seems to be also critical for working and spatial memory consolidation [19], with a characterized coupling between theta and gamma oscillations. From this point of view, REM would mediate the integration and recombination of memory traces previously consolidated during NREM sleep [20].

Figure 1. Role of sleep in memory consolidation. (a) During wakefulness, new memories are encoded by neuronal assemblies distributed within the neocortex and the hippocampal formation, integrating contextual information. During sleep, in absence of external inputs, memory reorganization is performed, reinforcing some neuronal assemblies by reactivation of the hippocampal-neocortical and thalamocortical circuits. Neural plasticity allows the consolidation of the stronger hippocampal-independent neocortical connections, together with the extinction of weak memory traces. (b) Neural oscillations hierarchically coupled allow memory processing during sleep. Slow oscillations propagate across cortical areas during Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep following a craneo-caudal direction, exhibiting upstates and downstates. During the downstates, neuronal rest is observed, while during upstates, highly synchronous discharges are observed, with replay of previous neuronal assemblies, coupled with sleep spindles originated in the thalamus. REM sleep is characterized by prominent theta waves in the hippocampal formation among other structures, coupled to gamma activity distributed within the neocortex. In this period, place-cells and grid cells exhibit a replay, allowing consolidation of contextual memory. Modified from Born and Wilhelm (2012) [21].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms21031168

References

- Marcos Gabriel Frank; Erasing Synapses in Sleep: Is It Time to Be SHY?. Neural Plasticity 2012, 2012, 1-15, 10.1155/2012/264378.

- Diane B. Howieson; Cognitive Decline in Presymptomatic Alzheimer Disease.. JAMA Neurology 2016, 73, 384-5, 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4993.

- Peigneux, P.; Smith, C. . Memory Processing in Relation to Sleep. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine; Kryger, M.; Roth, T.; Dement, W, Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: St Louis, USA, 2010; pp. 335-347.

- Qing-Fei Zhao; Lan Tan; Hui-Fu Wang; Teng Jiang; Meng-Shan Tan; Lin Tan; Wei Xu; Jie-Qiong Li; Jun Wang; Te-Jen Lai; et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2016, 190, 264-271, 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069.

- Alison Godbolt; Lisa Cipolotti; Hilary Watt; Nick Fox; John C. Janssen; M.N. Rossor; The Natural History of Alzheimer Disease. Archives of Neurology 2004, 61, 1743, 10.1001/archneur.61.11.1743.

- José Luis Molinuevo; Cinta Valls-Pedret; L. Rami; From mild cognitive impairment to prodromal Alzheimer disease: A nosological evolution. European Geriatric Medicine 2010, 1, 146-154, 10.1016/j.eurger.2010.05.003.

- Maria-Angeles Lloret; Ana Cervera-Ferri; Mariana Nepomuceno; Paloma Monllor; Daniel Esteve; Ana Lloret; Is Sleep Disruption a Cause or Consequence of Alzheimer’s Disease? Reviewing Its Possible Role as a Biomarker. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 1168, 10.3390/ijms21031168.

- Björn Rasch; J. Born; About sleep's role in memory.. Physiological Reviews 2013, 93, 681-766, 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012.

- Alexis M. Chambers; The role of sleep in cognitive processing: focusing on memory consolidation. WIREs Cognitive Science 2017, 8, e1433, 10.1002/wcs.1433.

- Marion Kuhn; Elias Wolf; Jonathan G. Maier; Florian Mainberger; Bernd Feige; Hanna Schmid; Jan Bürklin; Sarah Maywald; Volker Mall; Nikolai H. Jung; et al. Sleep recalibrates homeostatic and associative synaptic plasticity in the human cortex. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 12455, 10.1038/ncomms12455.

- Bernhard P. Staresina; Til Ole Bergmann; Mathilde Bonnefond; Roemer Van Der Meij; Ole Jensen; Lorena Deuker; Christian E. Elger; Nikolai Axmacher; Juergen Fell; Hierarchical nesting of slow oscillations, spindles and ripples in the human hippocampus during sleep. Nature Neuroscience 2015, 18, 1679-1686, 10.1038/nn.4119.

- Anton Sirota; György Buzsáki; Interaction between neocortical and hippocampal networks via slow oscillations. Thalamus & Related Systems 2005, 3, 245-259, 10.1017/S1472928807000258.

- György Buzsáki; Z Horváth; R Urioste; J Hetke; K Wise; High-frequency network oscillation in the hippocampus. Science 1992, 256, 1025-1027, 10.1126/science.1589772.

- A Ylinen; A Bragin; Zoltan Nadasdy; G Jandó; I Szabó; A Sik; György Buzsáki; Sharp wave-associated high-frequency oscillation (200 Hz) in the intact hippocampus: network and intracellular mechanisms. The Journal of Neuroscience 1995, 15, 30-46, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00030.1995.

- Nikolaus Maier; Volker Nimmrich; Andreas Draguhn; Cellular and Network Mechanisms Underlying Spontaneous Sharp Wave–Ripple Complexes in Mouse Hippocampal Slices. The Journal of Physiology 2003, 550, 873-887, 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044602.

- Thomas J. Davidson; Fabian Kloosterman; Matthew A. Wilson; Hippocampal Replay of Extended Experience. Neuron 2009, 63, 497-507, 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.027.

- Roy Cox; Anna C. Schapiro; Dara S. Manoach; Robert Stickgold; Individual Differences in Frequency and Topography of Slow and Fast Sleep Spindles. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2017, 11, 433, 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00433.

- Jens Klinzing; Niels Niethard; J. Born; Mechanisms of systems memory consolidation during sleep.. Nature Neuroscience 2019, 22, 1598-1610, 10.1038/s41593-019-0467-3.

- Mojtaba Bandarabadi; Richard Boyce; Carolina Gutierrez Herrera; Claudio L Bassetti; Sylvain Williams; Kaspar Anton Schindler; Antoine Adamantidis; Dynamic modulation of theta–gamma coupling during rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep 2019, 42, 169656, 10.1093/sleep/zsz182.

- Isabel C. Hutchison; Shailendra Rathore; The role of REM sleep theta activity in emotional memory. Frontiers in Psychology 2015, 6, 291, 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01439.

- J. Born; Ines Wilhelm; System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychological Research 2011, 76, 192-203, 10.1007/s00426-011-0335-6.