Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency is a rare monogenic disease due to mutations in the ddc gene producing AADC, a homodimeric pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent enzyme. The disorder is often fatal in the first decade and is characterized by profound motor impairments and developmental delay.

- aromatic amino acid deficiency

- homodimer

- heterodimer

- interallelic complementation

- structure-function relationship

- severity prediction

1. Introduction

Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency is a rare neurometabolic disease of monogenic inheritance leading to neurotransmitter imbalance and related severe motor and neurodevelopmental symptoms, such as hypokinesia, hypotonia, hypertonia, oculogyric crises (the hallmark of this disorder), developmental delay, and dystonia, as well as gastrointestinal and sleep problems. The first patients were described about thirty years ago [1]. In the presence of typical symptoms, the diagnosis of the disease is based on both the analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for metabolites related to AADC misfunctioning with a focus on the level of 3-O-methyldopa (3OMD), the byproduct of the accumulated substrate L-Dopa, and the determination of AADC activity in plasma [2]. This screening could then be followed and validated by genomic analyses [2]. However, as also underlined by the guidelines [2], diagnosis presents some weaknesses since the values of biogenic amines in CSF are overlapped in mild, moderate, and severe cases, and thus, they cannot be associated with the clinical phenotype. In addition, plasma AADC activity does not seem to distinguish clinical outputs since it is below the detection limit in many cases, irrespective of whether they are mild or severe [2]. Thus, at least in the less severe cases and in healthy carrier heterozygotes, diagnosis could be masked by other factors such as psychiatric symptoms due to serotonin imbalance.

The accepted clinical treatments foresee the supplementation with a drug combination: (i) vitamin B6, the precursor of the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP), the cofactor essential for AADC activity; (ii) a dopamine agonist, to supply the paucity of endogenous dopamine; iii) an inhibitor of monoamine oxidase to maintain the content of aromatic amines as high as possible (an in-depth analysis on clinical treatments is provided by other papers [2][3]).

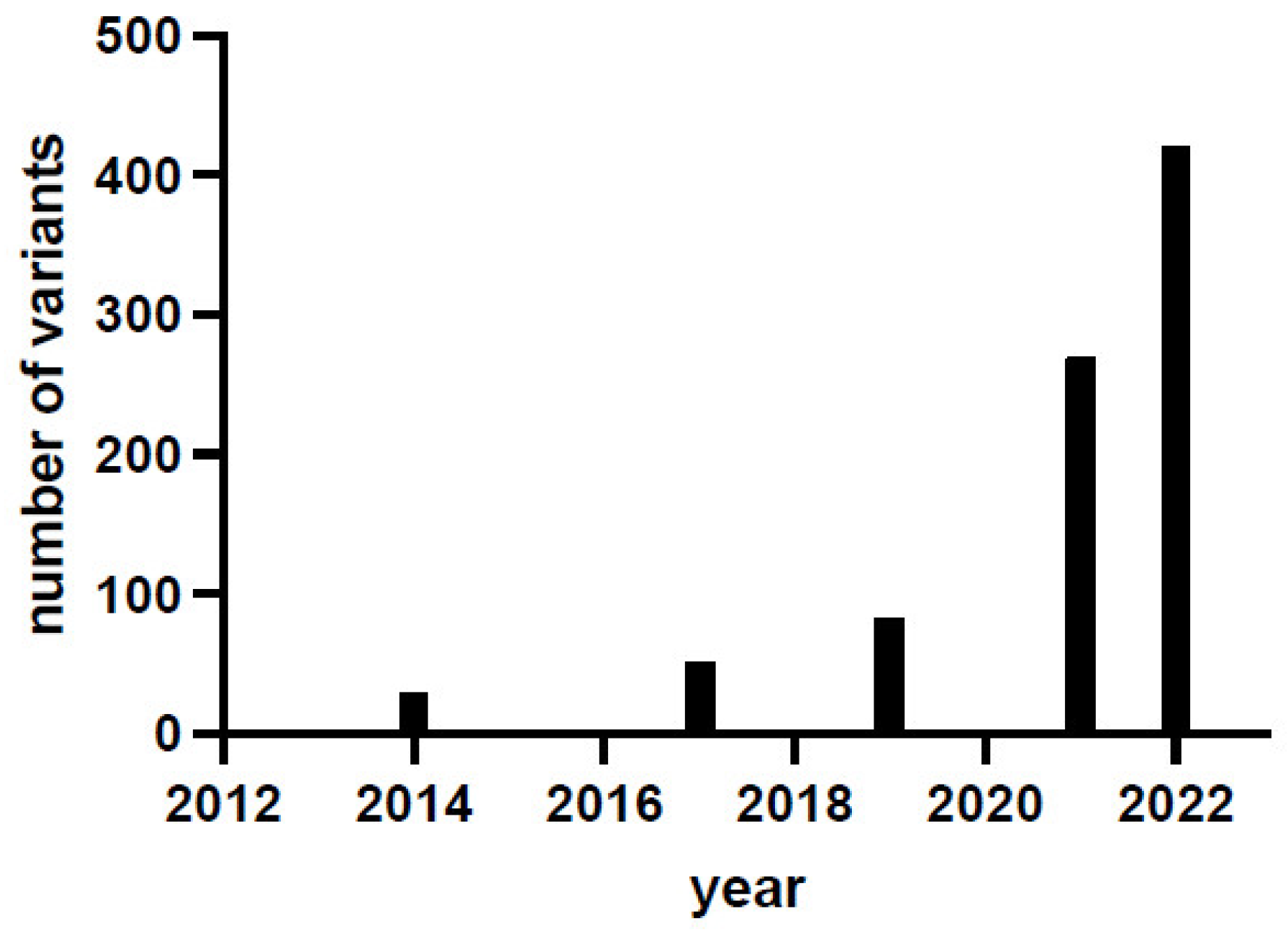

The last systematic collection of genetic and clinical data was published in 2019 and is based on 123 confirmed patients and 82 variants (71% missense, 11% splice, 11% insertions/deletions/duplications, 7% others) in 58 genotypes (33% in homozygosis and 67% in compound heterozygosis), and no clear genotype-to-phenotype correlation has been established [3]. In the last three years, there has been a marked increase in the number of identified variants, as shown by the locus-specific database PNDdb (http://biopku.org/home/pndbdb.asp accessed on 30 August 2022) that currently (August 2022) reports 420 variants, highlighting that the number of variants has exponentially increased (Figure 1), with the compound heterozygous genotype contributing over 70% of genotypes [4]. The clinical trials of gene therapy based on adeno-associated virus delivered either to the putamen [5][6][7][8][9][10] or to the midbrain [11][12] could have boosted the interest in this rare disease. Gene therapy represents a hope for many patients and is an undoubtful great step for the approach to this disease that has been neglected and misdiagnosed for a long time [13]. Indeed, recent data obtained via whole-genome and whole-exome sequence analyses together with biological samples screening [13] suggest that AADC deficiency is less ultra-rare than suspected.

Figure 1. AADC deficiency variant identification in the last decade. Data are taken from [2][3][14] and from the locus-specific database PNDdb (http://www.biopku.org/pnddb/search-results.asp accessed on 30 August 2022) at the end of December 2021 and of August 2022.

However, gene therapy has been applied taking into consideration the severity of the phenotype, irrespective of the genotype. This could lead to difficulties in interpreting the follow-up data, since the fully functioning AADC enzyme produced by the exogenous inoculation of its cDNA could be present concomitantly (or not) to endogenous AADC variant chains synthesized starting from the mutated gene. This would give rise to a complex AADC protein population.

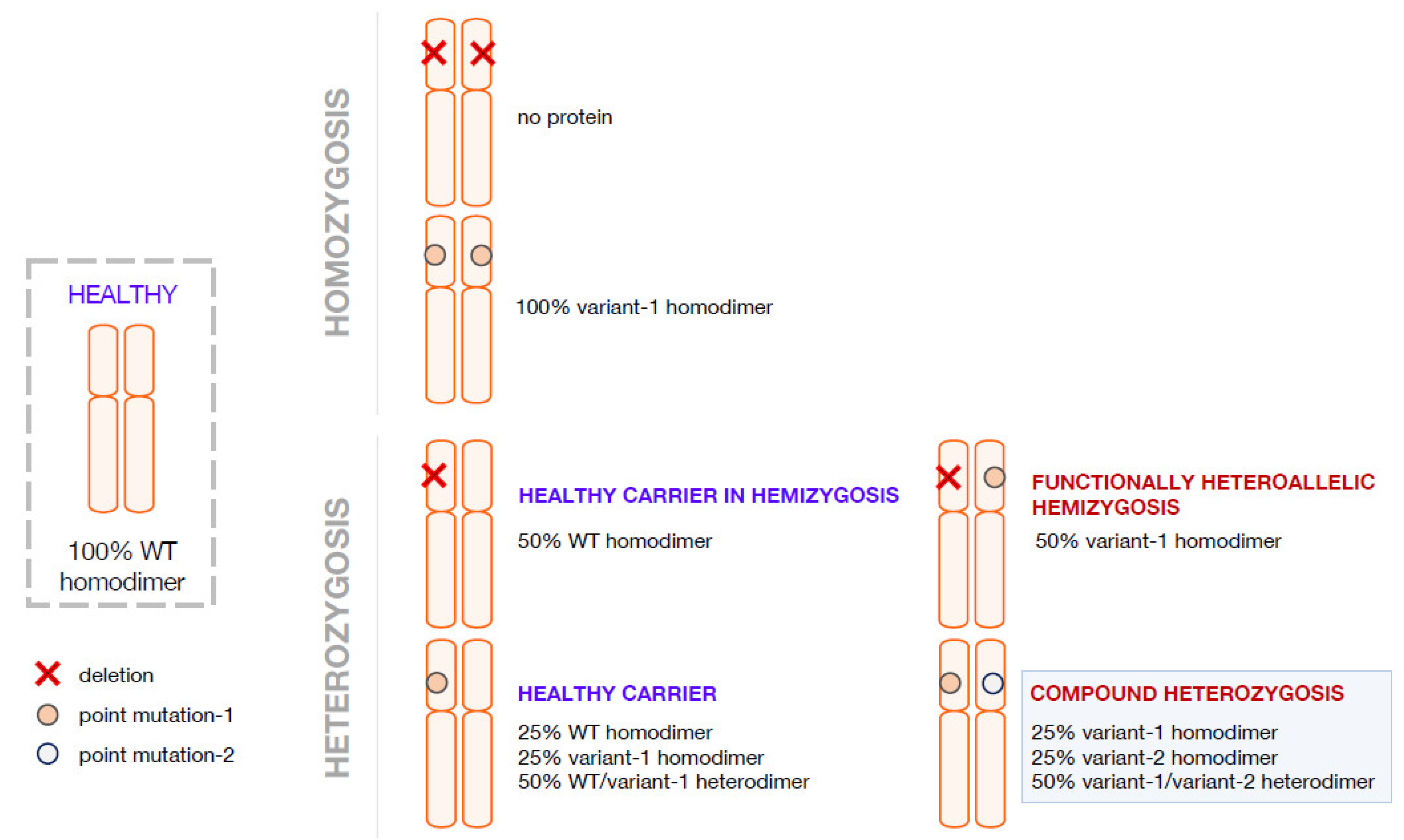

A contribution to the understanding of the severity/mildness of a phenotype arises from the characterization of the variant proteins aiming to determine the molecular cause responsible for the decreased activity of the variant species synthesized in the affected patients. The fact that a homozygote will produce only one type of AADC variant is more advantageous for structure-and-function correlation studies addressed to dissect the molecular basis for variant pathogenicity. Several papers have been focused on homodimeric AADC variants mimicking the AADC protein population of the homozygous patients, and an explanation for severe or mild clinical phenotype has been advanced and supported by structural and functional biochemical data, even if some inconsistencies have been observed and could be generally interpreted on the basis of individual genetic variability and environmental effects [14][15][16][17][18]. Overall, the investigation of protein machinery and its performance permits a reliable explanation of severity/mildness in homozygous AADC deficiency patients [17]. Interallelic heterozygosis determining functional hemizygosis arises when one allele leads to the synthesis of a variant polypeptide chain and the other is unable to do the same due to mutations in splicing sites or deletion. This leads to the production of only one type of variant enzyme, overlapping with what happens in homozygosis, unless in decreased amounts. Compound heterozygous patients would theoretically produce a mixed protein population with AADC homodimers and heterodimers (Figure 2). This complexity could prevent the dissection of the clinical phenotype. A further addition to complexity is the fact that it is unknown whether, in the presence of two alleles, there is a preference for homodimers or heterodimers or a combination thereof in mendelian terms. Moreover, protein folding or PLP binding and/or affinity complicate the situation from a predictive and mechanistic point of view.

Figure 2. Possible combination of alleles in AADC deficiency in homozygosis and in heterozygosis. Representation of possible allele combination in healthy, homozygous and heterozygous conditions is drawn. In blue are the supposed healthy individuals or theoretical healthy carriers; in red, the affected individuals.

The AADC enzymes produced by four AADC compound heterozygous patients have been characterized [4][19][20], revealing no apparent correlation between negative or positive complementation and clinical phenotype.

2. Compound Heterozygosis in AADC Deficiency

In the last few years, in an attempt to correlate AADC variants’ structural and functional features to the clinical phenotype, the researchers carried out an extensive investigation of the protein population theoretically present in four compound heterozygous patients [4][19][20]. In addition to the homodimers theoretically produced by these patients, the researchers also succeeded in expressing, producing, obtaining in good yields, and characterizing the heterodimers of each variant combination present in the patients. Results obtained with these heterodimeric species show that there is no apparent correlation between positive or negative interallelic complementation to the mildness/severity output of the clinical phenotype. In order to determine the individual effect of each variant present in the heterodimeric protein, the correlated homodimers were expressed and purified and their structural and functional features measured [4][14][19][20] since they could play a substantial role in the protein constellation (theoretically 50% of the AADC species) of each affected compound heterozygous patient. Unfortunately, only for two of these enzymatic variants was the homozygous patient identified, and the clinical phenotype correlates with the enzymatic features both for T69M and R347Q AADC variants [4][14].

Overall, the positive or negative complementation of a heterodimer does not seem to be related to the mild or severe effect on the activity of the less affected variant composing it, nor to the value of the catalytic constant kcat, nor to the affinity of the cofactor and, finally, nor to the clinical phenotype of the patient.

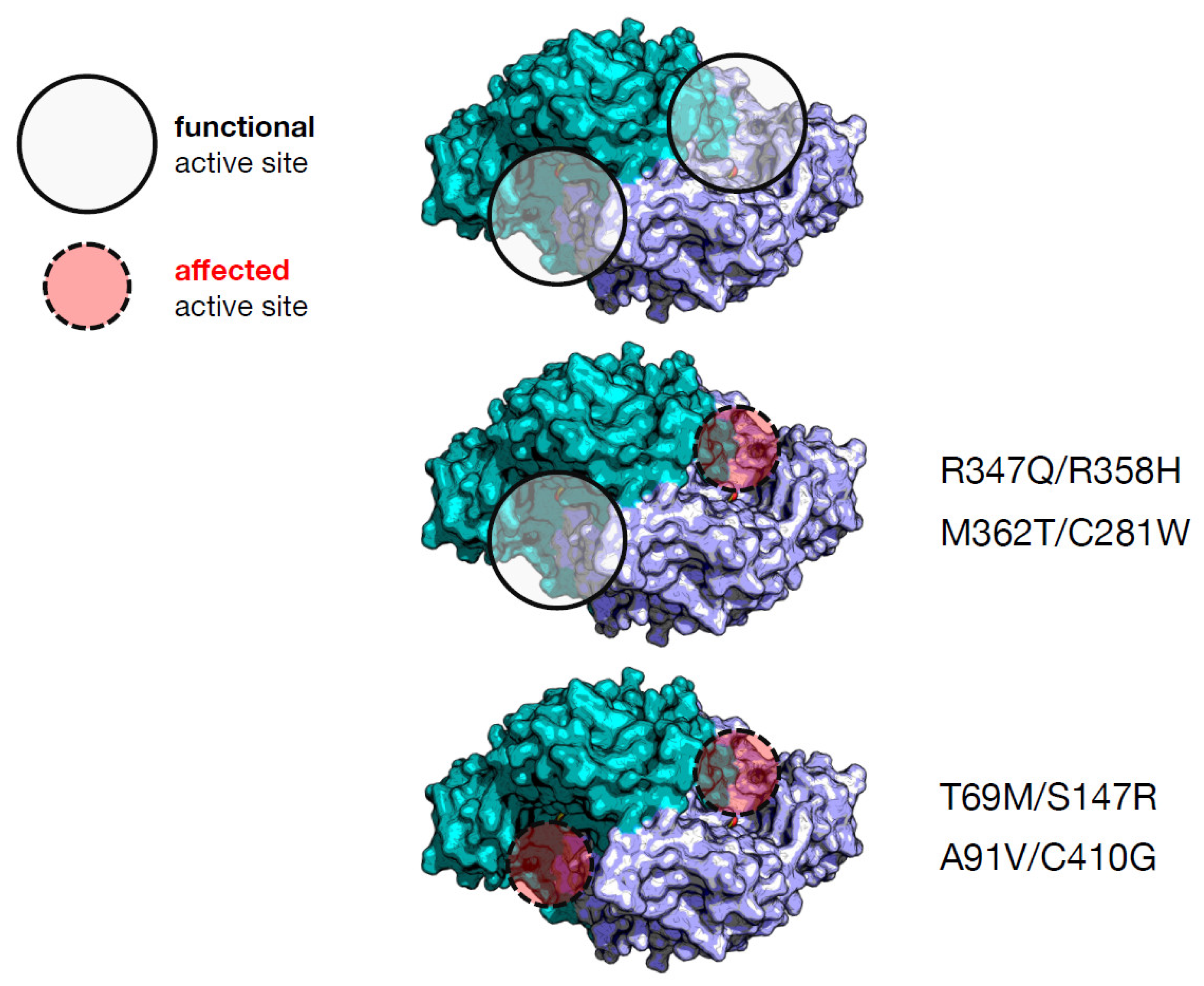

A rationale to predict the output of the interallelic complementation is the effect exerted by the single variants on both or only one active site [4]. Given the antisymmetric arrangement of the dimer [21] and the presence of loops protruding from one subunit to the other [22], each active site is composed by residues of both subunits. Following this view, the inspection of the crystal structure and bioinformatic analysis of in silico mutagenesis can predict that two severe homodimeric variants (R347Q and R358H) [14][19] could give rise to a heterodimeric combination where both amino acid substitutions affect the same active site, leaving the other site quite functioning to positively complement (Figure 3). On the other side, two mild ones (M362T and C281W) [4] affecting the same active site, as in M362T/C281W, could give rise to a negative complementation effect in activity, possibly due to the solubility problems of one of the subunits. The C281W homodimer could not be purified due to its high insolubility [4], a feature shared by other pathogenic variants of the same region, namely E283A [17] or R285W [14]. This could give rise to a protein with only one active site.

Figure 3. Possible effect on the active sites of AADC through combination of amino acid alterations in the heterodimers synthesized by compound heterozygous patients. The protein coordinates are taken from [21]. The two different colors refer to the functional AADC dimer displaying the antisymmetric arrangement. The circles are pointed on the active sites that could be altered or not by the amino acid alterations in the four heterodimers.

Instead, irrespective of severity or mildness of their homodimers (T69M, S147R, A91V and C410G) [4][14][15][20], the active sites of the related heterodimers (T69M/S147R, and A91V/C410G) are both affected, as revealed by the combination of bioinformatic inspection and kinetic assays, and thus, negative complementation takes place. A correlation between number of affected active sites and positive/negative complementation emerges for these four pathogenic AADC heterodimeric variants. However, there is no correlation with the clinical phenotype. In order to find a predictive marker of clinical output, the researchers observed that the catalytic parameter, kcat, for the heterodimeric proteins shows the following increasing trend: T69M/S147R, A91V/C410G, R347Q/R358H, and M362T/C281W. This tendency is not correlated to the values of the equilibrium dissociation constant for the PLP cofactor, which can be considered an indication of the degree of structural damage of the active site. T69M/S147R and R347Q/R358H are the two less structurally affected heterodimers in terms of PLP affinity, but the related compound heterozygous patients are the most affected. Since the C281W variant is poorly soluble and is presumed to have folding difficulties given the exposure of a substituted apolar residue at the place of a polar one [4], it can influence allele combination in patients and the relative abundance in a homodimer–heterodimer equilibrium. Overall, residual activity of recombinant protein variants as well as interallelic complementation could not correlate to the clinical phenotype, since other factors should be taken into consideration, such as protein folding, PLP binding, and the number of active sites compromised by amino acid substitutions. It is also evident that these observations are based on complete characterization of a limited number of genotypes, and more research should be carried out to reinforce interpretation and/or provide new suggestions.

Interestingly, the researchers' data agree with what was found by [23] in terms of clinical prediction since severity/mildness seems to be dictated (at least for dimeric enzymes) not by the mild substitution in terms of activity but by the combination of factors involving structural and functional elements of the active sites of the affected protein.

It would be worthwhile to find a strategy to precisely define mild, attenuated, and severe AADC deficiency in order to apply the APV algorithm that could be very informative. Meanwhile, a combination of studies on the recombinant enzyme species in solution and in silico as well as transfection into appropriate cell models of the variant cDNAs with multi-tag vectors could be an informative approach to predict phenotype and understand allele dominance.

3. Pathogenic Heterozygosity in AADC Deficiency

Heterozygous individuals in AADC deficiency are defined as healthy carriers and usually represent the parents of the affected patients. However, widespread reports in the literature deal with cases of heterozygosity associated with clinical signs. These are normally referred to as mild patients, but with some exceptions. In 2018, Portaro et al. [24] published the case of a woman affected by behavioral problems who was diagnosed in adulthood with S250F AADC heterozygosity and died before starting therapy. Since the phenotype in S250F homozygosis is attenuated [14][18], it is tricky to understand the reason for pathogenicity. The authors concluded that the symptoms were not so evident and only overlapped with those of AADC deficiency and that the presence of the mutation in heterozygosis alleviates clinical outputs. In addition, the paper shows that the patient possessed other mutations in other genes identified by next-generation sequence analyses, suggesting the relevance of the whole genetic inheritance. Another case was reported by [25] involving a AADC heterozygous individual (case II-2) that reached adulthood but presented with severe cerebral palsy and mental disability, microcephaly, and spastic–dystonic tetraparesis with dystonic scoliosis. The metabolic profile in plasma shows some values similar to those of the affected compound heterozygous siblings, such as homovanillic acid and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (markers of affected aromatic amino acids L-Dopa and L-5-hydroxytryptophan imbalance), but activity in plasma was about half that of both her parents (one of whom with her identical genotype in the gene for AADC) (Table 1 in [25]). These results were not commented on but indicate that heterozygous carriers could also show some disease signs.

Finally, the Taiwan list of patients published by [26] shows the presence, among others, of patient number 37 (Table 1 in [26]) who is heterozygous for AADC carrying the splicing mutation C.714 + 4A > T on one allele. This mutation is the result of a typical founder effect and is very severe both in homozygosis and in heterozygosis [2][3][26]. Patient 37 presents with a mild phenotype possibly due to compensation by the WT allele, leading to a protein pool with only WT AADC, unless decreased in amounts.

This implies on one hand the importance of a registry comprising not only the affected patients but also the natural history of the parents, siblings, and the whole families, as the International Working Group on Neurotransmitter Related Diseases (iNTD) registry aims to collect (https://www.intd-registry.org/ accessed on 30 August 2022). On the other hand, caution should be taken in considering all heterozygous individuals as healthy carriers. To researchers, it would be worthwhile to compare CSF metabolic profiles and plasma AADC activity of a large familiar “bucket”; to clinicians, to be aware of psychiatric, depression, and behavioral problems.

In addition, the comparison of the genomic data not confined to AADC but to other possible variants in other proteins for the enlarged family could offer some hints for possible interplay between AADC and other factors.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms231911238

References

- Hyland, K.; Clayton, P.T. Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in twins. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1990, 13, 301–304.

- Wassenberg, T.; Molero-Luis, M.; Jeltsch, K.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Assmann, B.; Blau, N.; Garcia-Cazorla, A.; Artuch, R.; Pons, R.; Pearson, T.S.; et al. Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 12.

- Himmelreich, N.; Montioli, R.; Bertoldi, M.; Carducci, C.; Leuzzi, V.; Gemperle, C.; Berner, T.; Hyland, K.; Thöny, B.; Hoffmann, G.F.; et al. Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: Molecular and metabolic basis and therapeutic outlook. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 127, 12–22.

- Longo, C.; Montioli, R.; Bisello, G.; Palazzi, L.; Mastrangelo, M.; Brennenstuhl, H.; de Laureto, P.P.; Opladen, T.; Leuzzi, V.; Bertoldi, M. Compound heterozygosis in AADC deficiency: A complex phenotype dissected through comparison among heterodimeric and homodimeric AADC proteins. Mol. Genet. Metab 2021, 134, 147–155.

- Hwu, W.L.; Muramatsu, S.; Tseng, S.H.; Tzen, K.Y.; Lee, N.C.; Chien, Y.H.; Snyder, R.O.; Byrne, B.J.; Tai, C.H.; Wu, R.M. Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 134ra161.

- Chien, Y.H.; Lee, N.C.; Tseng, S.H.; Tai, C.H.; Muramatsu, S.I.; Byrne, B.J.; Hwu, W.L. Efficacy and safety of AAV2 gene therapy in children with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: An open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2017, 1, 265–273.

- Hwu, P.W.; Kiening, K.; Anselm, I.; Compton, D.R.; Nakajima, T.; Opladen, T.; Pearl, P.L.; Roubertie, A.; Roujeau, T.; Muramatsu, S.I. Gene therapy in the putamen for curing AADC deficiency and Parkinson’s disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, e14712.

- Tai, C.H.; Lee, N.C.; Chien, Y.H.; Byrne, B.J.; Muramatsu, S.I.; Tseng, S.H.; Hwu, W.L. Long-term efficacy and safety of eladocagene exuparvovec in patients with AADC deficiency. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 509–518.

- Kojima, K.; Nakajima, T.; Taga, N.; Miyauchi, A.; Kato, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Ikeda, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kubota, T.; Mizukami, H.; et al. Gene therapy improves motor and mental function of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain 2019, 142, 322–333.

- Onuki, Y.; Ono, S.; Nakajima, T.; Kojima, K.; Taga, N.; Ikeda, T.; Kuwajima, M.; Kurokawa, Y.; Kato, M.; Kawai, K.; et al. Dopaminergic restoration of prefrontal cortico-putaminal network in gene therapy for aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab078.

- Bankiewicz, K.S.; Pasterski, T.; Kreatsoulas, D.; Onikijuk, J.; Mozgiel, K.; Munjal, V.; Elder, J.B.; Lonser, R.R.; Zabek, M. Use of a novel ball-joint guide array for magnetic resonance imaging-guided cannula placement and convective delivery: Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 135, 651–657.

- Pearson, T.S.; Gupta, N.; San Sebastian, W.; Imamura-Ching, J.; Viehoever, A.; Grijalvo-Perez, A.; Fay, A.J.; Seth, N.; Lundy, S.M.; Seo, Y.; et al. Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency by MR-guided direct delivery of AAV2-AADC to midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4251.

- Hyland, K.; Reott, M. Prevalence of Aromatic l-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency in At-Risk Populations. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 106, 38–42.

- Montioli, R.; Dindo, M.; Giorgetti, A.; Piccoli, S.; Cellini, B.; Voltattorni, C.B. A comprehensive picture of the mutations associated with aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: From molecular mechanisms to therapy implications. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 5429–5440.

- Montioli, R.; Cellini, B.; Borri Voltattorni, C. Molecular insights into the pathogenicity of variants associated with the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 1213–1224.

- Montioli, R.; Paiardini, A.; Kurian, M.A.; Dindo, M.; Rossignoli, G.; Heales, S.J.R.; Pope, S.; Voltattorni, C.B.; Bertoldi, M. The novel R347g pathogenic mutation of aromatic amino acid decarboxylase provides additional molecular insights into enzyme catalysis and deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1864, 676–682.

- Montioli, R.; Bisello, G.; Dindo, M.; Rossignoli, G.; Voltattorni, C.B.; Bertoldi, M. New variants of AADC deficiency expand the knowledge of enzymatic phenotypes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 682, 108263.

- Montioli, R.; Oppici, E.; Cellini, B.; Roncador, A.; Dindo, M.; Voltattorni, C.B. S250F variant associated with aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: Molecular defects and intracellular rescue by pyridoxine. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1615–1624.

- Montioli, R.; Janson, G.; Paiardini, A.; Bertoldi, M.; Borri Voltattorni, C. Heterozygosis in aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: Evidence for a positive interallelic complementation between R347Q and R358H mutations. IUBMB Life 2018, 70, 215–223.

- Montioli, R.; Battini, R.; Paiardini, A.; Tolve, M.; Bertoldi, M.; Carducci, C.; Leuzzi, V.; Borri Voltattorni, C. A novel compound heterozygous genotype associated with aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: Clinical aspects and biochemical studies. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 127, 132–137.

- Burkhard, P.; Dominici, P.; Borri-Voltattorni, C.; Jansonius, J.N.; Malashkevich, V.N. Structural insight into Parkinson’s disease treatment from drug-inhibited DOPA decarboxylase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001, 8, 963–967.

- Paiardini, A.; Giardina, G.; Rossignoli, G.; Voltattorni, C.B.; Bertoldi, M. New Insights Emerging from Recent Investigations on Human Group II Pyridoxal 5′-Phosphate Decarboxylases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 226–244.

- Hübschmann, O.K.; Juliá-Palacios, N.A.; Olivella, M.; Guder, P.; Zafeiriou, D.I.; Horvath, G.; Kulhánek, J.; Pearson, T.S.; Kuster, A.; Cortès-Saladelafont, E.; et al. Integrative Approach to Predict Severity in Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia. Ann. Neurol. 2022, 92, 292–303.

- Portaro, S.; Gugliandolo, A.; Scionti, D.; Cammaroto, S.; Morabito, R.; Leonardi, S.; Fraggetta, F.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. When dysphoria is not a primary mental state: A case report of the role of the aromatic L-aminoacid decarboxylase. Medicine 2018, 97, e10953.

- Leuzzi, V.; Mastrangelo, M.; Polizzi, A.; Artiola, C.; van Kuilenburg, A.B.; Carducci, C.; Ruggieri, M.; Barone, R.; Tavazzi, B.; Abeling, N.G.; et al. Report of two never treated adult sisters with aromatic L-amino Acid decarboxylase deficiency: A portrait of the natural history of the disease or an expanding phenotype? JIMD Rep. 2015, 15, 39–45.

- Hwu, W.L.; Chien, Y.H.; Lee, N.C.; Li, M.H. Natural History of Aromatic L-Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency in Taiwan. JIMD Rep. 2018, 40, 1–6.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!