Cancer immunotherapies, such as ICIs and CAR-T, have dramatically altered the treatment landscape for many solid and hematologic malignancies [124,187]. Ongoing research continues to investigate ways to harness the immune system to treat cancer and broaden the indications for currently available therapies. Although immunotherapies have revolutionized the treatment of solid and hematologic malignancies, they have unique toxicity profiles based on their mode of action [131,132]. Despite this, such innovative therapies can potentially increase already-in-use therapies’ effectiveness.

- FDA

- checkpoint inhibitors

- monoclonal antibody

- CAR-T

- CAR NK

- Trastuzumab

- Enhertu

- PD-1

- PDL-1

1. Cancer Immunity and Immune Evasion

2. Immune Checkpoints

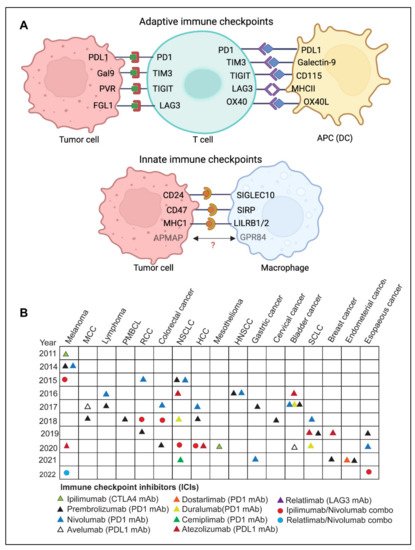

2.1. Adaptive Immune Checkpoints

CTLA-4

PD-1

LAG-3

TIGIT

TIM-3

B7-H3 and B7-H4

VISTA

OX40/OX40L

A2A/B-R and CD73

NKG2A

2.2. Innate Immune Checkpoints

SIRPα-CD47

LILRB1/MHC-I and LILRB2/MHC-I

Siglec10-CD24

APMAP

2.3. Limitations and Challenges of ICI Therapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been employed as immunotherapeutic agents in treating various malignancies [124]. Immunotherapy has the potential to elicit long-lasting responses in a subset of patients with advanced diseases that can be maintained for several years after treatment cessation [125]. Compared to chemotherapy or targeted therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy exhibits various tumor response patterns, such as delayed response, durable response, dissociated pseudoprogression, and hyperprogression [126]. One of the limitations of ICI therapies is the lack of reliable predictive biomarkers of durable response and limited understanding of clinically relevant determinants of pseudo or hyper progression. No standard definition of durable responses to ICI-based therapies has been devised, and optimal treatment duration in case of durable response has not been established [125,126].

ICIs have shown remarkable success in inducing durable responses in several patients with malignant disease; however, these therapies confer distinct toxicities, depending on the type of therapy used [131]. Although acute toxicities are more frequent, chronic immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which happen in some patients, are becoming more recognized [131]. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are a distinct range of adverse effects of ICI therapies that resemble autoimmune reactions [132]. Clinical trial data analysis indicates that irAEs are estimated to occur in a significant proportion of cancer patients undergoing ICI therapies [23]. Since irAEs often result from immune system hyperactivation, this suggests that the exhausted immune cells have been reinvigorated to attack both tumor and the normal cells [131,132].

Another limitation of ICI-based therapies is primary and acquired resistance. Although immune checkpoint therapy has been shown to have persistent response rates, many patients do not benefit from it, often called primary resistance. However, some responders experience a relapse of the metastatic disease after their initial response, also known as acquired resistance. Such types of heterogeneous responses have been observed in various metastatic lesions, even within the same patient [134]. This resistance is influenced by both extrinsic tumor microenvironmental variables and tumor intrinsic factors. The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment created due to the presence of Tregs, M2 macrophages, MDSCs, and other inhibitory immune checkpoints largely contribute to acquired resistance [135]. Tumor resistance is also influenced by the absence of tumor antigen, loss or downregulation of MHC-I, alterations in the antigen-presentation, and inadequate immune cell infiltration. [134,136].

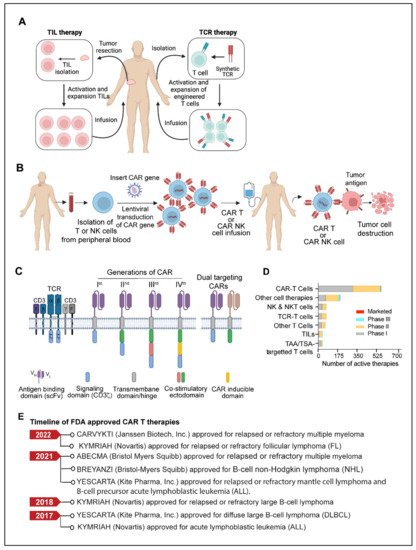

3. Adoptive Cell Therapy

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) is another fast-emerging field of cancer immunotherapy in which a patient’s cells are genetically engineered ex-vivo and then transferred back to the patient’s body as therapeutic agents. T cell based adoptive cell therapies such as TILs (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes), Synthetic TCRs (engineered T-cell receptors) and CAR T (chimeric antigen receptor T cells) and NK cells based therapies called CAR-NK have been developed.

3.1. TILs (Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes)

3.2. TCR (T Cell Receptor) Therapy

3.3. CAR T Cells

3.4. CAR-NK Cell

3.5. Limitations and Challenges of CAR T Therapy

CAR T cell therapy has several limitations, which include antigen escape, antigen heterogeneity, trafficking of CAR T cells and tumor infiltration, immunosuppressive microenvironment, and CAR-T cell-associated toxicities [204]. One of the most challenging limitations of CAR-T cell therapy is the emergence of tumor resistance to single antigen targeting CAR constructs. Despite the ability of single antigen CAR-T cells to induce a potent response, some malignant cells in patients can exhibit a partial or complete loss of target antigen expression. This mechanism is known as antigen escape [204,205]. Recent follow-up data from relapsed and/or refractory ALL patients and multiple myeloma treated with CD19 CAR-T therapy or B-cell maturation antigens (BCMA) targeted CAR-T cells indicates that the incidence of resistance to therapy in a small percentage of patients is due to the loss of CD19 and BCMA [204,205,206,207,208]. Although CAR-T therapies have shown great potential in treating hematological cancers, their efficacy remains undetermined in solid tumors. Targeting solid tumor antigens is challenging since many of these antigens are often expressed to varying extents by normal tissues. Antigen selection is, therefore, critical for CAR-T cell design to enhance therapeutic effectiveness and reduce off-target effects. [204].

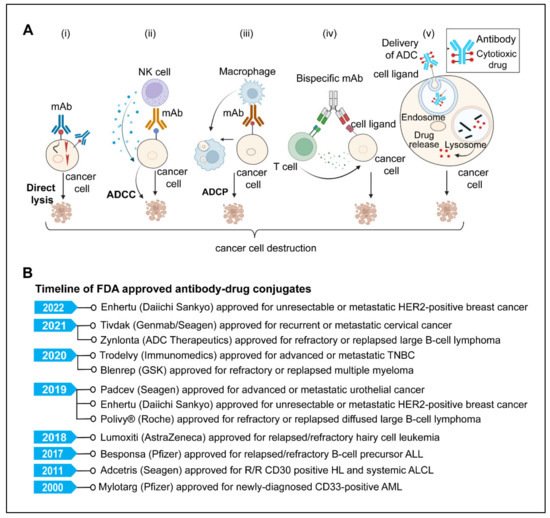

4. Monoclonal Antibodies

4.1. Direct Killing and Immune-Mediated Killing

MAbs, upon antigen-specific binding to tumor-associated antigens, induce cytotoxic effects either by neutralizing or killing through cell-intrinsic proapoptotic signaling mechanisms [219,222,224]. One example is Trastuzumab, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody that inhibits cancer cell growth by interfering with HER2 dimerization and intracellular signaling [219,220]. The immune-mediated mechanism involves antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP).

4.2. mAbs Targeting Angiogenesis

4.3. Antibody-Drug Conjugates

4.4. Antibody Radioimmunoconjugate (RIC)

4.5. Bispecific Antibodies

5. Cytokine Therapies

Cytokines are immune system components that play an important role in the cancer immunity cycle; however, the expression and activity of many cytokines are dysregulated in malignancies [270,271,272]. The first cytokine to be used in the treatment of cancer was IL-2. It is considered not only the first cytokine therapy but also the first reproducible and effective human cancer immunotherapy [273]. The U.S. FDA approved IL-2 in 1992 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and in 1998, subsequently, it was later approved for metastatic melanoma [274]. Though high-dose IL-2 monotherapy demonstrated encouraging outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, its use remained limited due to toxicity and high production costs [273,274]. Another challenge with IL-2 is that it can activate both cancer-killing effector T cells as well as immunosuppressive regulatory T cells. Therefore, further research is required to better understand the complex biology of IL-2 to harness its utility as cancer immunotherapy. One of the fundamental limitations of cytokine therapy is the pleiotropic effect of cytokines [270,280]. Each cytokine can affect numerous cell types that elicit both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses [270,276]. The expensive cost of manufacture, the need for producing clinically required doses to elicit a reliable immunological response, as well as the short half-life and systemic toxicity, are further barriers to the effectiveness of cytokine therapy [270,276,277].

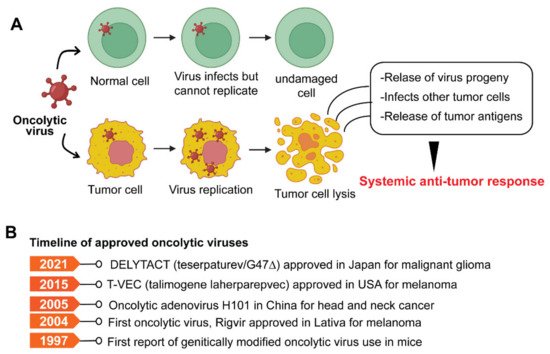

6. Oncolytic Viruses

7. Cancer Vaccines

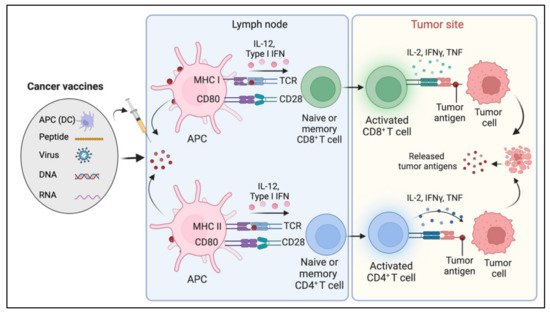

Cancer vaccines stimulate the immune system to mount an antitumoral response and protect against cancer [124,293]. Cancer vaccines are typically classified as either prophylactic or preventative or therapeutic. Prophylactic vaccines protect against oncogenic virus infection. Therapeutic vaccinations, on the other hand, harness the potential of the immune system to eradicate neoplastic cells. [292,293]. Therapeutic cancer vaccines involve the exogenous administration of specific tumor antigens to the patient to activate their adaptive immune system and elicit an anti-tumor response [293] (Figure 6).

Typically, therapeutic cancer vaccines target two classes of antigens, tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and tumor-specific antigens (TSAs). TAAs are self-antigens that may be expressed to some degree in a subset of normal cells but are either abnormally or preferentially expressed on tumor cells. TSAs are tumor-specific, arising from oncogenic viruses or oncogenic driver mutations that generate neoantigens [302]. Therapeutic cancer vaccines are divided into four categories depending on the various formulation methods and delivery systems: nucleic acids (DNA or RNA)-based vaccines, viruses-based vaccines, peptide-based vaccines, and cell-based vaccines [292]. Vaccines that utilize whole cells such as autologous antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells (DCs) as antigen carriers are called cell-based cancer vaccines. Peptide-based vaccines comprise predicted epitopes of tumor antigen. Virus-based vaccines utilize viral vectors expressing the target tumor antigen. DNA vaccines may encode TAA or immunomodulatory factors to induce tumor antigen-specific response. mRNA cancer vaccine formulations comprise in vitro synthetic mRNA encoding a single or multiple antigens. Each of these has some advantage over the other, reviewed elsewhere [292,303].

Although cancer vaccines have shown tremendous preclinical promise, many fail in therapeutic settings. There have been several setbacks in therapeutic vaccine development [292,300]. One of the most critical constraints has been antigen selection [305]. Although the concept of neoantigens has emerged, predicting which neoantigens can elicit a robust antitumor response remains a daunting task [302]. Cancer vaccines have been unsuccessful in patients with ‘cold tumors’ which are refractory to immunotherapy [18]. ‘Cold tumors’ are typically characterized by a low infiltration of effector T cells in the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, a low mutational load, and a low neoantigen burden. [227]. Many cancer vaccines have failed to elicit clinical efficacy, partly due to the tumor’s immune evasion and escape mechanisms such as loss of antigenicity, loss of MHC-I, presence of an immune suppressive tumor microenvironment, and a paucity of a strong antitumor immune response [226].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diseases10030060