Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Rare diseases are defined as uncommon conditions with a prevalence of less than 50 per 100,000 (1 in 2000) people or less than 200,000 people in the US. Among all rare diseases, urea cycle disorder (UCD) and phenylketonuria (PKU) are associated with executive dysfunction.

- rare diseases

- executive dysfunction

- brain biomarkers

- urea cycle disorder

1. Urea Cycle Disorder (UCD)

The urea cycle disorders (UCD) are a group of genetic disorders associated with an enzyme or a carrier protein insufficiency [1][2]. Table 1 shows the specific UCD and prevalence. Removing ammonia, a neurotoxic substance, from the blood is hindered in the UCD. Accumulation of ammonia, namely, hyperammonia (HA), can cause severe brain damage and encephalopathy in several of the UCD [3]. The cognitive sequelae may range from mild to severe executive dysfunction and working memory impairment to intellectual disability and seizures [4][5]. There are several methods to investigate brain function and structure during HA such as electroencephalography (EEG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). These modalities allow for the non-invasive monitoring of disease prognostic, brain-neurological dysfunction and brain-related pathophysiology of UCD. fNIRS offers portability, and immediate availability in a patient who is too hemodynamically unstable to transport to the MRI suite.

Table 1. The specific UCD disorders and estimated prevalence [6].

| UCD Disorders | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) | 1:14,000 |

| Argininosuccinate synthase (AS) deficiency (Citrullinemia) | 1:57,000 |

| Carbamyl phosphate synthase I (CPSI) deficiency | 1:62,000 |

| Argininosuccinate lyase (AL) deficiency (Argininosuccinic aciduria) | 1:70,000 |

| Arginase (ARG) deficiency (Argininemia) | 1:350,000 |

| N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS) deficiency | unknown |

| Citrullinemia type II (Mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier deficiency-CITR) |

1 in 21,000 in Japan |

| Hyperornithinemia, hyperammonemia, homocitrullinuria (HHH) syndrome (Or mitochondrial ornithine carrier deficiency-ORNT) |

unknown |

One of the main focuses in studying brain function in UCD is to understand the pathogenesis of brain dysfunction and its temporal correlation to the HA. It has been postulated that there is a critical age or stage for HA to cause irreversible dysfunction. It is also important to know if there are differences between UCDs in their mechanism of brain damage [6].

In 2003, the urea cycle disorder consortium (UCDC) was established under the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Since then, research centers and clinical research to address gaps in treatment and monitoring of UCD patients have grown.

In order to answer the questions relating to brain dysfunction, early efforts were made by the UCDC [7]. Focusing on the mechanisms of neuronal injury secondary to HA, they concluded that the major consequence of UDC is neurological, but it is unclear whether the HA was the only contributor to the pathogenesis. For instance, glutamine could also play a role. Other key studies included measuring urea production in patients with urea cycle defects in vivo [8], a randomized, double-blind, crossover study of sodium phenylbutyrate and low-dose arginine (100 mg/kg/day)compared to high-dose arginine alone on liver function, ureagenesis and subsequent nitric oxide production in patients with argininosuccinate lyase (AL) deficiency [2], and carbamylglutamate treatment of n-acetyl glutamate synthetase deficiency (NAGS) [9][10]. Among these studies, only Gropman et al. considered imaging modalities for investigating the neurological manifestation of the disease [11][12].

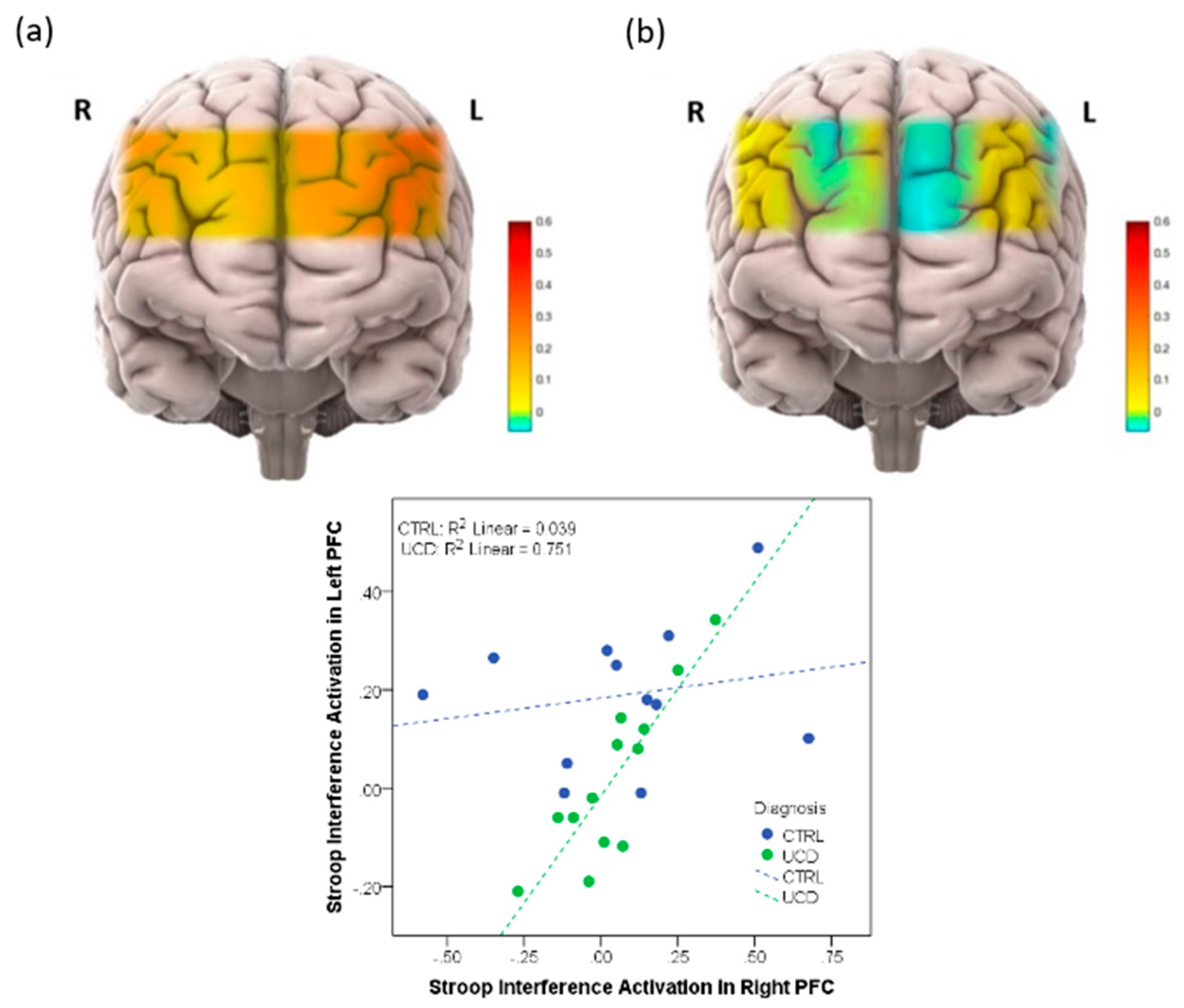

As referenced above, neurological impairment is of primary significance to the UCD [7][13]. For decades, EEG and MRI have been the main modalities for studying neurological dysfunction in the UCD [1]. fNIRS has emerged as a non-invasive technique and could serve as a surrogate to fMRI with better portability in assessing hemodynamic change in the brain and further assist the development of new imaging biomarkers [14]. Like other biomarkers, information forms a single modality and can be misleading in a clinical setting due to the inherent limitation of likelihood ratios. Thus, combining neuroimaging modalities has been considered so that the data from multiple imaging modalities can overcome the incomplete information from individual modalities. The portability of fNIRS is particularly important when working with children and toddlers, but also with populations who will have difficulty remaining still in a scanner or have claustrophobia. Multimodal imaging with EEG and fNIRS was introduced as potential real-time imaging for detection and treatment of brain injuries due to UCD and HA. Figure 1 illustrates the activation map and the difference between ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) subjects and normal controls during a Stroop task that resulted from this study. A lower activation during the Stroop task was seen in patients with OTCD [13]. These results confirm the fMRI outcomes in OTCD patients. A significant change in brain activation was also seen in BOLD signal on PFC of OTDC patients using fMRI compared to healthy controls [12].

Figure 1. (Top): (a) Activation map in prefrontal cortex (PFC) in healthy volunteers, (b) Activation map in prefrontal cortex in patients with UCD. (Bottom): Correlation between right and left PFC in subjects with and without UCD.

Two published articles used fNIRS to measure brain activation in UCD patients. Anderson et al. measured brain activation in prefrontal cortex (PFC) on OTCD patients when they performed the Stroop task [11]. In this study, the differences in brain activation in left and right PFC in patients with OTCD and controls was assessed. It was found that control subjects demonstrated a higher task-related activation increase, whereas subjects with OTCD also exhibited bilateral increase in PFC activation. This was in the absence of a significant difference in response time or correct responses. They concluded that fNIRS can provide a unique opportunity to monitor OTCD progression and examine neurocognitive changes. This work confirmed the activation pattern found using fMRI through an N-back task that showed a higher dorsolateral PFC activation in patients with OTCD [12]. The second work from Anderson et al. was a twin study to examine the hemodynamics of PFC in a fraternal twin with and without OTCD [15]. They quantified the hemodynamics of the brain as measured by fNIRS while subjects performed the N-back working memory task. Results demonstrated that the sibling with OTCD showed higher variation in a very low frequency band (related to cerebral autoregulation) compared to the control sibling. The difference between these variations was not as obvious in the higher frequency band, indicating the possible autoregulation impairment and cognitive dysfunction due to the presence of HA. This work was the first to show the efficacy of fNIRS in monitoring patients with UCD and indicated the possibility of inefficient neurocognitive function. Sen et al. in their review paper on UCD research, reviewed these works and mentioned that they believed fNIRS could provide a novel and non-invasive tool to monitor OTCD progression and to examine neurocognitive changes [1]

2. Phenylketonuria(PKU)

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a genetic autosomal recessive disorder that causes the amino acid phenylalanine to accumulate in the body. In the United States, the incidence of PKU is approximately 1 in 10,000. Different ethnicities also have different prevalence (1 in 8000 among Caucasians and 1 in 50,000 among African Americans) [16]. The defect that results in PKU is found on chromosome 12 at the locus 12q24.1 [16] and is caused by a defect in the phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) gene that helps create the enzyme needed to break down phenylalanine. Without the enzyme to process phenylalanine, a dangerous buildup of phenylalanine (Phe) can develop when a person with PKU eats foods that contain protein with high amounts of Phe.

PKU is the first known inherited cause of intellectual disability in pediatrics [17]. Infants in the United States and many other countries are screened for PKU soon after birth. Recognizing PKU early on can help prevent significant health problems. Patients show neurological abnormalities, intellectual disability, poor motor function, microcephaly, epilepsy and pyramidal tract dysfunction [18]. Universal newborn screening pioneered by Dr. Ronald Scott and the introduction of low phenylalanine diet in 1953 by Bickel et al. [19] have made the serious side effects of PKU become a rare incidence.

Although the serious side effects of PKU have been greatly prevented, the subtle or subclinical neurological changes can still be seen, especially in adults with high Phe level [20]. Therefore, the correlation between the Phe level and cortical function is still of great interest for researchers and clinicians. PKU is the best studied inborn error of metabolism about the impact of elevated Phe levels on the brain and its impact on executive function. Several imaging modalities have been used to study PKU, but only some of them targeted the brain functional activity of this population. Thompson et al., (1993) reported MRI findings of 34 subjects [18].

In addition to the structural changes, the functional aspect of the brain has also been explored in individuals with PKU. Christ et al. have looked at brain function in PKU and have done the most in PKU using fMRI [21]. They reported atypical PFC neural activity in PKU patients during N-back working memory tasks. They also tested the PKU-related functional connectivity impairments compared to normal controls and found decreased connectivity within and between the PFC (and other brain regions) in PKU patients. Their results are consistent with previous behavioral analysis which showed the prefrontal dysfunction in this cohort [22][23].

Abgottspon et al. examined the neural activity and working memory performance in individuals with PKU compared to controls using fMRI [24]. Their cohort was early-treated adults with PKU and aged matched normal adult controls. They concluded that cognitive performance and neural activity is altered in PKU patients which is related to metabolic dysfunction due to the disease. They showed a lower prefrontal activation compared to normal controls. A lower accuracy in responses was also seen in patients with PKU during the fMRI task, but the response time was comparable to controls. This indicates the reduced working memory performance in the PKU population.

Sundermann et al., in their 2020 work, tested a Go-No-Go task in young females with PKU using fMRI. Higher incidents of errors and altered activation were also reported by this group. Their results supported the presence of cognitive dysfunction in the PKU cohort [25]. Using fMRI and N-back task, Trepp et al. defined a clinical study of cognitive deficits in PKU as a part of a large study on this cohort [26].

Mentioning the neuroimaging studies on PKU, fNIRS along with fMRI as imaging modalities of choice for studying the brain dysfunction and impairment in this population. fMRI’s limitations, such as sensitivity to motion, made it a challenging method for the study of PKU patients due to their poor motor function. fNIRS, however, can be an ideal modality that provides increased flexibility to investigate neurological dysfunction in PKU due to its uniqueness in terms of wireless functionality, portability, and insensitivity to motion.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/genes13101690

References

- Sen, K.; Anderson, A.A.; Whitehead, M.T.; Gropman, A.L. Review of Multi-Modal Imaging in Urea Cycle Disorders: The Old, the New, the Borrowed, and the Blue. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 632307.

- Lee, B.; Garcia-Prats, J.A.; Hahn, S. Urea Cycle Disorders: Clinical Features and Diagnosis; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 1–22. Available online: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/urea-cycle-disorders-clinical-features-and-diagnosis (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Ribas, G.S.; Lopes, F.F.; Deon, M.; Vargas, C.R. Hyperammonemia in Inherited Metabolic Diseases. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 1–18.

- Waisbren, S.E.; Stefanatos, A.K.; Kok, T.M.Y.; Ozturk-Hismi, B. Neuropsychological attributes of urea cycle disorders: A systematic review of the literature. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 1176–1191.

- Waisbren, S.E.; Gropman, A.L.; Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium (UCDC); Batshaw, M.L. Improving Long Term Outcomes in Urea Cycle Disorders-Report from the Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. Off. J. Soc. Study Inborn Errors Metab. 2016, 39, 537–584.

- Seminara, J.; Tuchman, M.; Krivitzky, L.; Krischer, J.; Lee, H.-S.; LeMons, C.; Baumgartner, M.; Cederbaum, S.; Diaz, G.A.; Feigenbaum, A.; et al. Establishing a consortium for the study of rare diseases: The Urea Cycle Disorders Consortium. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010, 100, S97–S105.

- Gropman, A.L.; Summar, M.; Leonard, J.V. Neurological implications of urea cycle disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007, 30, 865–879.

- Yudkoff, M.; Mew, N.A.; Daikhin, Y.; Horyn, O.; Nissim, I.; Nissim, I.; Payan, I.; Tuchman, M. Measuring in vivo ureagenesis with stable isotopes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010, 100, S37–S41.

- Tuchman, M.; Caldovic, L.; Daikhin, Y.; Horyn, O.; Nissim, I.; Nissim, I.; Korson, M.; Burton, B.; Yudkoff, M. N-carbamylglutamate markedly enhances ureagenesis in N-acetylglutamate deficiency and propionic acidemia as measured by isotopic incorporation and blood biomarkers. Pediatr. Res. 2008, 64, 213–217.

- Mew, N.A. N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency: An insight into the genetics, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2011, 4, 127–135.

- Anderson, A.A.; Gropman, A.; Le Mons, C.; Stratakis, C.A.; Gandjbakhche, A.H. Evaluation of neurocognitive function of prefrontal cortex in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2020, 129, 207–212.

- Gropman, A.L.; Shattuck, K.; Prust, M.J.; Seltzer, R.R.; Breeden, A.L.; Hailu, A.; Rigas, A.; Hussain, R.; VanMeter, J. Altered neural activation in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency during executive cognition: An fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 34, 753–761.

- Gropman, A.L.; Anderson, A. Novel imaging technologies for genetic diagnoses in the inborn errors of metabolism. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2020, 4, 429–445.

- Wagner, J.C.; Zinos, A.; Chen, W.-L.; Conant, L.; Malloy, M.; Heffernan, J.; Quirk, B.; Sugar, J.; Prost, R.; Whelan, J.B.; et al. Comparison of Whole-Head Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy With Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Potential Application in Pediatric Neurology. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 122, 68–75.

- Anderson, A.A.; Gropman, A.; Le Mons, C.; Stratakis, C.A.; Gandjbakhche, A.H. Hemodynamics of Prefrontal Cortex in Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency: A Twin Case Study. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 809.

- Phillips, M.D.; McGraw, P.; Lowe, M.J.; Mathews, V.P.; Hainline, B.E. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging of White Matter Abnormalities in Patients with Phenylketonuria. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2001, 22, 1583–1586.

- Karimzadeh, P.; Ahmadabadi, F.; Jafari, N.; Shariatmadari, F.; Nemati, H.; Ahadi, A.; Dardashti, S.K.; Mirzarahimi, M.; Dastborhan, Z.; Noghabi, J.Z. Study on MRI Changes in Phenylketonuria in Patients Referred to Mofid Hospital/Iran. Iran. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 8, 53–56.

- Thompson, A.; Tillotson, S.; Smith, I.; Kendall, B.; Moore, S.G.; Brenton, D.P. Brain MRI changes in phenylketonuria: Associations with dietary status. Brain 1993, 116, 811–821.

- Bickel, H. Influence of phenylalanine intake on phenylketonuria. Lancet Ii 1953, 812.

- Jaulent, P.; Charriere, S.; Feillet, F.; Douillard, C.; Fouilhoux, A.; Thobois, S. Neurological manifestations in adults with phenylketonuria: New cases and review of the literature. J. Neurol. 2019, 267, 531–542.

- Christ, S.E.; Moffitt, A.J.; Peck, D. Disruption of prefrontal function and connectivity in individuals with phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010, 99, S33–S40.

- White, D.A.; Nortz, M.J.; Mandernach, T.; Huntington, K.; Steiner, R.D. Deficits in memory strategy use related to prefrontal dysfunction during early development: Evidence from children with phenylketonuria. Neuropsychology 2001, 15, 221.

- White, D.A.; Nortz, M.J.; Mandernach, T.; Huntington, K.; Steiner, R.D. Age-related working memory impairments in children with prefrontal dysfunction associated with phenylketonuria. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2002, 8, 1–11.

- Abgottspon, S.; Muri, R.; Christ, S.E.; Hochuli, M.; Radojewski, P.; Trepp, R.; Everts, R. Neural correlates of working memory and its association with metabolic parameters in early-treated adults with phenylketonuria. NeuroImage: Clin. 2022, 34, 102974.

- Sundermann, B.; Garde, S.; Dehghan Nayyeri, M.; Weglage, J.; Rau, J.; Pfleiderer, B.; Feldmann, R. Approaching altered inhibitory control in phenylketonuria: A functional MRI study with a Go-NoGo task in young female adults. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 52, 3951–3962.

- Trepp, R.; Muri, R.; Abgottspon, S.; Bosanska, L.; Hochuli, M.; Slotboom, J.; Rummel, C.; Kreis, R.; Everts, R. Impact of phenylalanine on cognitive, cerebral, and neurometabolic parameters in adult patients with phenylketonuria (the PICO study): A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover, noninferiority trial. Trials 2020, 21, 178, Erratum in Trials 2020, 21, 561.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!