Fossil fuel divestment or fossil fuel divestment and investment in climate solutions is an attempt to reduce climate change by exerting social, political, and economic pressure for the institutional divestment of assets including stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments connected to companies involved in extracting fossil fuels. Fossil fuel divestment campaigns emerged on campuses in the United States in 2010 with students urging their administrations to turn endowment investments in the fossil fuel industry into investments in clean energy and communities most impacted by climate change. By 2015, fossil fuel divestment was reportedly the fastest growing divestment movement in history. In April 2020, a total of 1,192 institutions and over 58,000 individuals representing $14 trillion in assets worldwide had begun or committed to a divestment from fossil fuels.

- climate change

- fossil fuel

- climate

1. Motivations for Divestment

1.1. Reducing Carbon Emissions

Fossil fuel divestment aims to reduce carbon emissions by accelerating the adoption of the renewable energy transition through the stigmatisation of fossil fuel companies. This includes putting public pressure on companies that are currently involved in fossil fuel extraction to invest in renewable energy.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that all future carbon dioxide emissions must be less than 1,000 gigatonnes to provide a 66% chance of avoiding dangerous climate change; this figure includes all sources of carbon emissions. To avoid dangerous climate change, only 33% of known extractable fossil fuel of known reserves can be used; this carbon budget can also be depleted by an increase in other carbon emission sources such as deforestation and cement production. It is claimed that, if other carbon emissions increase significantly, then only 10% of the fossil fuel reserves can be used to stay within projected safe limits.[1]

Furthermore, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, Earth's average temperature has risen by 0.78 °C (1.4 °F) over the past century, and is predicted to rise another 1.1 to 6.4 °C (2 to 11.5 °F) over the next hundred years with continued carbon emission rates. This rise in temperature would far pass the level of warming that scientists have deemed safe to support life on earth.[2]

I think this is part of a process of delegitimising this sector and saying these are odious profits, this is not a legitimate business model ... This is the beginning of the kind of model that we need, and the first step is saying these profits are not acceptable and once we collectively say that and believe that and express that in our universities, in our faith institutions, at city council level, then we’re one step away from where we need to be, which is polluter pays.—Naomi Klein (author of This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate), The Guardian , 2014.[3]

1.2. Acting on the Paris Agreement

Toronto Principle

This Agreement [...] aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, [...] including by [...] Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C and [...] Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development. — Paris Agreement, article 2 (2015).[4]

The Toronto Principle is a fossil fuel divestment strategy, which puts into action the aims set forth at the Paris Agreement in 2015. It was first coined by Benjamin A. Franta, in an article in the Harvard Crimson, as a reference to the University of Toronto's fossil fuel divestment process.[5]

After 350.org submitted a petition for divestment on 6 March 2014, President Gertler established an ad hoc Advisory Committee on Divestment from Fossil Fuels.[6] In December 2015, the Committee released a report with several recommendations. Foremost, they argued that "targeted and principled divestment from companies in the fossil fuels industry that meet certain criteria...should be an important part of the University of Toronto’s response to the challenges of climate change."[7] However, the report went further, and allied itself with the Paris Agreement. It recommended that the university divest from companies that "blatantly disregard the international effort to limit the rise in average global temperatures to not more than one and a half degrees Celsius above pre-industrial averages by 2050...These are fossil fuels companies whose actions are irreconcilable with achieving internationally agreed goals."[7]

Franta identified this response as the Toronto Principle, which, as he argues, "aligns rhetoric and action. It suggests that it is all institutions' responsibility to give life to the Paris agreement. Harvard could adopt this Toronto principle, too, and the world would be better for it."[8] Franta also identified how the Toronto Principle would be put into practice, which includes "moving investments away from coal companies and coal-fired power plants, companies seeking non-conventional or aggressive fossil fuel development (such as oil from the Arctic or tar sands), and possibly also companies that distort public policies or deceive the public on climate. At present, these activities are incompatible with the agreement in Paris."[1] In adhering to the Toronto Principle, Franta argues that leading institutions can use their status and power to meaningfully respond to the challenge of climate change, and act based on the goals at the Paris Agreement.

Lofoten Declaration

The Lofoten Declaration (2017) calls for curtailing hydrocarbon exploration and expansion of fossil fuel reserves. It demands fossil fuel divestment and phase-out of use with a just transition to a low-carbon economy. The Declaration calls for early leadership in these efforts from the economies that have benefited the most from fossil fuel extraction.

1.3. Economic

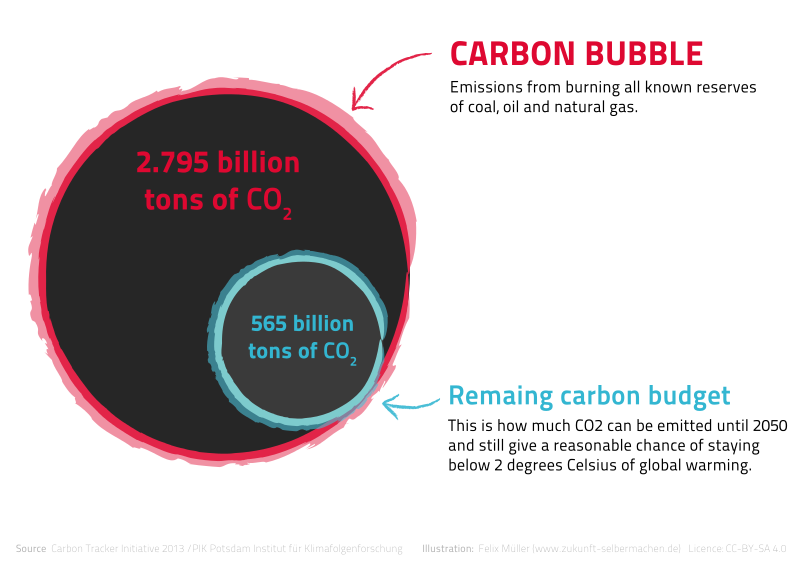

Stranded assets – the carbon bubble

Stranded assets, which are known in relation to fossil fuel companies as the carbon bubble, occur when the reserves of fossil fuel companies are deemed environmentally unsustainable and so unusable and so must be written off. Currently the price of fossil fuels companies' shares is calculated under the assumption that all of the companies' fossil fuel reserves will be consumed, and so the true costs of carbon dioxide in intensifying global warming is not taken into account in a company's stock market valuation.[9]

| Fuel | United States | Africa | Australia | China and India | Ex-Soviet Republics | Arctic | Worldwide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | 92% | 85% | 90% | 66% | 94% | 0% | 82% |

| Gas | 4% | 33% | 61% | 63% | 50% | 100% | 49% |

| Oil | 6% | 21% | 38% | 25% | 85% | 100% | 33% |

In 2013 a study by HSBC found that between 40% and 60% of the market value of BP, Royal Dutch Shell and other European fossil fuel companies could be wiped out because of stranded assets caused by carbon emission regulation.[10] Bank of England governor Mark Carney, speaking at the 2015 World Bank seminar, has stated: "The vast majority of reserves are unburnable" if global temperature rises are to be limited to below 2 °C.[11] In 2019, Carney suggested that banks should be forced to disclose their climate-linked risks within the next two years, and said that more information would prompt investors to penalise and reward firms accordingly.[12] He warned that companies and industries that are not moving towards zero-carbon emissions could be punished by investors and go bankrupt.[13]

In June 2014, the International Energy Agency released an independent analysis on the effect of carbon emissions controls. This estimated that $300 billion in fossil-fuel investments would be stranded by 2035 if cuts in carbon emissions are adopted so that the global mean surface temperature increases by no more than 2 °C.[14]

A report by the Carbon Tracker Initiative found that between 2010 and 2015 the US coal sector had lost 76% of its value including the closure of 200 mines. It found that Peabody Energy, the world's largest private coal mining company, had lost 80% of its share price over this time. This was attributed to Environmental Protection Agency regulations and competition from shale gas.[15]

In 2013, fossil fuel companies invested $670 billion in exploration of new oil and gas resources.[16]

Risk of regulation and carbon pricing

A 2015 report studied 20 fossil fuel companies and found that, while highly profitable, the hidden economic cost to society was also large.[17][18] The report spans the period 2008–2012 and notes that: "for all companies and all years, the economic cost to society of their CO

2 emissions was greater than their after‐tax profit, with the single exception of ExxonMobil in 2008."[17]:4 Pure coal companies fare even worse: "the economic cost to society exceeds total revenue (employment, taxes, supply purchases, and indirect employment) in all years, with this cost varying between nearly $2 and nearly $9 per $1 of revenue."[17]:4,5 The paper suggests:

This hidden or externalised cost is an implicit subsidy and accordingly represents a risk to those companies. There is a reasonable chance that society will act to either reduce this societal cost by regulating against fossil fuel use or recover it by imposing carbon prices. Investors are increasingly focused on this risk and seeking to understand and manage it."[17]:2

Similarly, in 2014, financial analyst firm Kepler Cheuvreux projected $28 trillion in lost value for fossil fuel companies under a regulatory scenario that targets 450 parts per million of atmospheric CO

2.[19][20]

Competition from renewable energy sources

Competition from renewable energy sources may lead to the loss of value of fossil fuel companies due to their inability to compete commercially with the renewable energy sources.[21] In some cases this has already happened.[22] Deutsche Bank predicts that 80% of the global electricity market will have reached grid parity for solar electricity generation by the end of 2017.[23] In 2012, 67% of the world's electricity generation was produced from fossil fuels.[24]

Stanwell Corporation, an electricity generator owned by the Government of Queensland made a loss in 2013 from its 4,000 MW of coal and gas fired generation capacity. The company attributed this loss to the expansion of rooftop solar generation which reduced the price of electricity during the day; on some days the price (usually AUD$40–50/MWh) was almost zero.[22][25] The Australian Government and Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecast the production of energy by rooftop solar to rise sixfold between 2014 and 2024.[22]

Unstable fossil fuel prices

Unstable fossil fuel prices has made investment in fossil fuel extraction a more risky investment opportunity. West Texas Intermediate crude oil fell in value from $107 per barrel in June 2014 to $50 per barrel in January 2015. Goldman Sachs stated in January 2015 that, if oil were to stabilize at $70 per barrel, $1 trillion of planned oilfield investments would not be profitable.[10]

2. Effects of Divestment

2.1. Stigmatization of Fossil Fuel Companies

A study by the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at the University of Oxford found that the stigmatisation of fossil fuel companies caused by divestment can "materially increase the uncertainty surrounding the future cash flows of fossil-fuel companies."[26] That, in turn, "can lead to a permanent compression in the trading multiples – e.g., the share price to earnings (P/E) ratio of a target company."[26]

The study also says that:

The outcome of the stigmatisation process poses the most far-reaching threat to fossil fuel companies. Any direct impacts pale in comparison.[26]2.2.

2.2. Financial Impact

Despite social effects, direct financial impacts are often reported as negligible by financial research studies.

According to a 2013 study by the Aperio Group, the economic risks of disinvestment from fossil fuel companies in the Russell 3000 Index are "statistically irrelevant".[27]

According to a 2019 analysis by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, the energy sector portion of the S&P 500, which is dominated by fossil fuels, has underperformed the overall index since 1989. [28]

3. Legal Cases

In November 2014, a group of seven undergraduate, graduate, and law students filed a lawsuit at the Suffolk County Superior Court against the president and fellows of Harvard College and others for "mismanagement of charitable funds" and "intentional investment in abnormally dangerous activities" in relation to Harvard's investments in fossil-fuel companies.[29] In March 2015, the superior court granted Harvard's motion to dismiss. The superior judge wrote: "Plaintiffs have brought their advocacy, fervent and articulate and admirable as it is, to a forum that cannot grant the relief they seek."[30]

4. Reaction from the Fossil-Fuel Industry

In October 2014, Exxon Mobil stated that the fossil-fuel divestment was "out of step with reality" and that "to not use fossil fuels is tantamount to not using energy at all, and that's not feasible."[10]

In March 2014, John Felmy, the chief economist of the American Petroleum Institute, stated that the movement to divest from fossil-fuel companies "truly disgusts me" and stated that academics and campaigners who support divestment are misinformed, uninformed or liars. Felmy particularly criticized the environmentalist and author Bill McKibben.[31]

The World Coal Association has pointed out that divesting from the fossil fuel industry does not necessarily result in a reduction of demand for fossil fuels, rather it would result in environmentally conscious investors losing influence over the operation of those companies. In fact, coal has been the fastest growing energy source over the last decade and is an important raw material for steel and cement in developing countries.[32]

5. Exponential Growth Into a Global Divestment Movement

From half a dozen college campuses in 2011, calling on their administrations to divest endowments from coal and other fossil fuels and invest in clean energy and "just transition" strategies to empower those most impacted by environmental degradation and climate change, the campaign had spread to an estimated 50 campuses in spring 2012.[33] By September 2014, 181 institutions and 656 individuals had committed to divest over $50 billion.[8] One year later, by September 2015, the numbers had grown to 436 institutions and 2,040 individuals across 43 countries, representing $2.6 trillion in assets, of which 56% were based on the commitment of pension funds and 37% of private companies.[33] By April 2016, already 515 institutions had joined the pledge, of which 27% faith-based groups, 24% foundations, 13% governmental organisations, 13% pension funds and 12% colleges, universities and schools, representing, together with the individual investors, a total of $3.4 trillion in assets.[34] In April of 2020, the number of institutions had grown to 1192, with a total combined asset value of $14,14 trillion.[35]

6. Groups Involved in Divestment Campaigns

6.1. Fossil Free ANU

The divestment campaign at the Australian National University is one of the longest running in the world and, while it has not yet achieved full fossil fuel divestment, it has had substantial wins, most notably in 2011 and 2014.

Fossil Free ANU formed out of the ANU Environment Collective (EC), a consensus-based and non-hierarchical group of students affiliated with the Australian Student Environment Network, when students were notified in 2011 by campaigners at the Northern Rivers, NSW that ANU was the 12th largest shareholders in the coal seam gas company Metgasco.[36] Following student protests, including an event called 'ANU Gets Fracked' that saw students erect a mock gas rig in Union Court, the ANU Council announced in October 2013 that it would divest from Metgasco, citing student concerns and the fact that the Australian Ethical Investment did not approve of them.[37] Tom Stayner, an activist from the EC, stated in the ANU student paper Woroni that: "He took some convincing, but the Vice Chancellor is showing leadership on this urgent issue."[38]

However, student concerns were again raised in 2012 when it was revealed that the ANU had only reduced its holding in Metgasco from over 4 million shares in 2011 to 2.5 million in 2012.[39] In 2013, Tom Swann filed a FOI request to the ANU requesting all "documents created during 2012, which refer to the University's purchase, sale or ownership of shares in any company which generates revenue from oil, coal, gas, or uranium."[40] These documents revealed that ANU had substantial holdings in major fossil fuel companies and had been buying shares in Santos while selling shares in Metgasco.[41] Students lobbying and public pressure led the ANU Council to implement a Socially Responsible Investment Policy (SRI) in late 2013 modelled on Stanford University, which aims to "avoid investment opportunities considered to be likely to cause substantial social injury."[41]

In 2014, students from Fossil Free ANU organised the first student-initiated referendum at the ANU and in elections in September more than 82 per cent of students voted in favour of the ANU divesting from fossil fuels in what was the highest turnout in a student election at the university in more than a decade.[42] In October 2014, the ANU Council announced that it would divest from seven companies, two of which, Santos and Oil Search, performed poorly in an independent review undertaken by the Centre for Australian Ethical Research.[43] This decision provoked a month-long controversy with the Australian Financial Review publishing over 53 stories criticising the decision including 12 front pages attacking the ANU, with its editor-in-chief, Michael Stutchbury, prouncing the decision to be as "disingenuous" as banning the burqa.[42] These attacks, which The Canberra Times editorial described as "verging on hysterical"[44] was joined by members of the cabinet of the Abbott Government, with the Treasurer Joe Hockey stating that the ANU Council is "removed from the reality of what is helping to drive the Australian economy and create more employment,"[45] Education Minister Christopher Pyne calling it "bizarre"[46] and Prime Minister Tony Abbott calling it "stupid."[47] In response, Louis Klee, an activist from Fossil Free ANU, wrote in The Age that the reaction demonstrated not just "the complicity of state power with the mining industry," but also:

[...] that the citizens of this country are powerful voices in the debate over climate justice. It demonstrates that they are, ultimately, voices speaking with growing eloquence, urgency and authority for one thing: action to address global climate change.[42]

Vice-Chancellor of ANU Ian Young stood by the decision, stating:

On divestment, it is clear we were in the right and played a truly national and international leadership role. ... [W]e seem to have played a major role in a movement which now seems unstoppable.[48]

Meeting with students in the wake of the furore of the decision, Ian Young told activists from Fossil Free ANU that while he initially thought divestment was "a sideshow," the reaction of the mining companies revealed that students "were right all along."[49]

ANU still has holdings in fossil fuel companies and Fossil Free ANU continues to campaign for ANU to 'Divest the Rest'.[43]

6.2. 350.org

350.org is an international environmental organization encouraging citizens to action with the belief that publicizing the increasing levels of carbon dioxide will pressure world leaders to address climate change and to reduce levels from 400 parts per million to 350 parts per million. As part of its global policy, 350.org launched their Go Fossil Free: Divest from Fossil Fuels! campaign in 2012, which campaign calls for colleges and universities, as well as cities, religious institutions, and pension funds to withdraw their investments from fossil fuel companies.

6.3. Divest-Invest Philanthropy

Divest-Invest Philanthropy is an international platform for institutions committed to fossil fuel divestment.[50][51]

6.4. The Guardian

In March 2015, The Guardian launched the 'Keep it in the ground' campaign encouraging the Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to divest from fossil fuel companies in which the foundation has a minimum of $1.4 billion invested.[52] The Wellcome Trust has £450m of investments in Shell, BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and BP.[52] The petition had received over 140,000 signatures by the end of March 2015.[53]

The Guardian itself stopped accepting advertisements from the fossil fuel industry in January 2020.[54]

6.5. Fossil Free Stanford

Fossil Free Stanford is one of the highest-profile university divestment campaigns in the U.S. In May 2014, the university divested its endowment, then valued at US$18.7 billion, from holdings in coal extraction companies following a sustained campaign by undergraduate students.[55] Author Naomi Klein called the divestment, "the most significant victory in the youth climate movement to date."[56]

The campaign maintains widespread support on the campus, exemplified in multiple all-campus referenda, including in April 2014 and April 2018, in which the student body voted 75 percent and 81 percent in favor of divestment from all fossil fuels, respectively.[57] The Stanford Undergraduate Senate and Stanford Graduate Student Council also both passed resolutions calling for full fossil fuel divestment in 2014.[58][59] In 2016, the student body Presidents and Vice Presidents from both the 2016–2017 school year and the 2015–2016 school year published a letter calling for the university's leadership to represent the student consensus in support of fossil fuel divestment.[60]

In January 2015, a group of more than 300 Stanford faculty published a letter calling for full divestment, which garnered international attention.[61] Additional faculty signed on in the following weeks such that the total grew to 457 faculty signatories.[62] Signatories included a former president of the university, multiple department chairs, a vice provost, multiple Nobel Laureates, and members of all seven of the university's schools.[63]

In November 2015, in advance of the UNFCCC COP 21 climate negotiations that resulted in the Paris Agreement, over 100 students risked arrest by staging a non-violent sit-in, surrounding the university president's office for 5 days and 4 nights.[64] The sit-in ended when the university's president, John Hennessy, agreed on the fifth day to a public meeting with the student group.[65] In response to the students' publicized plans to hold this sit-in, the university's Board of Trustees published a letter to the UNFCCC calling for bold climate action.[66]

In April 2016, the university's Board announced that it would take no further divestment action related to fossil fuel divestment. In response, a group of over 1000 students and Alumni pledged during the school's graduation ceremonies in June 2016 to withhold all future donations until the school achieved full divestment.[67]

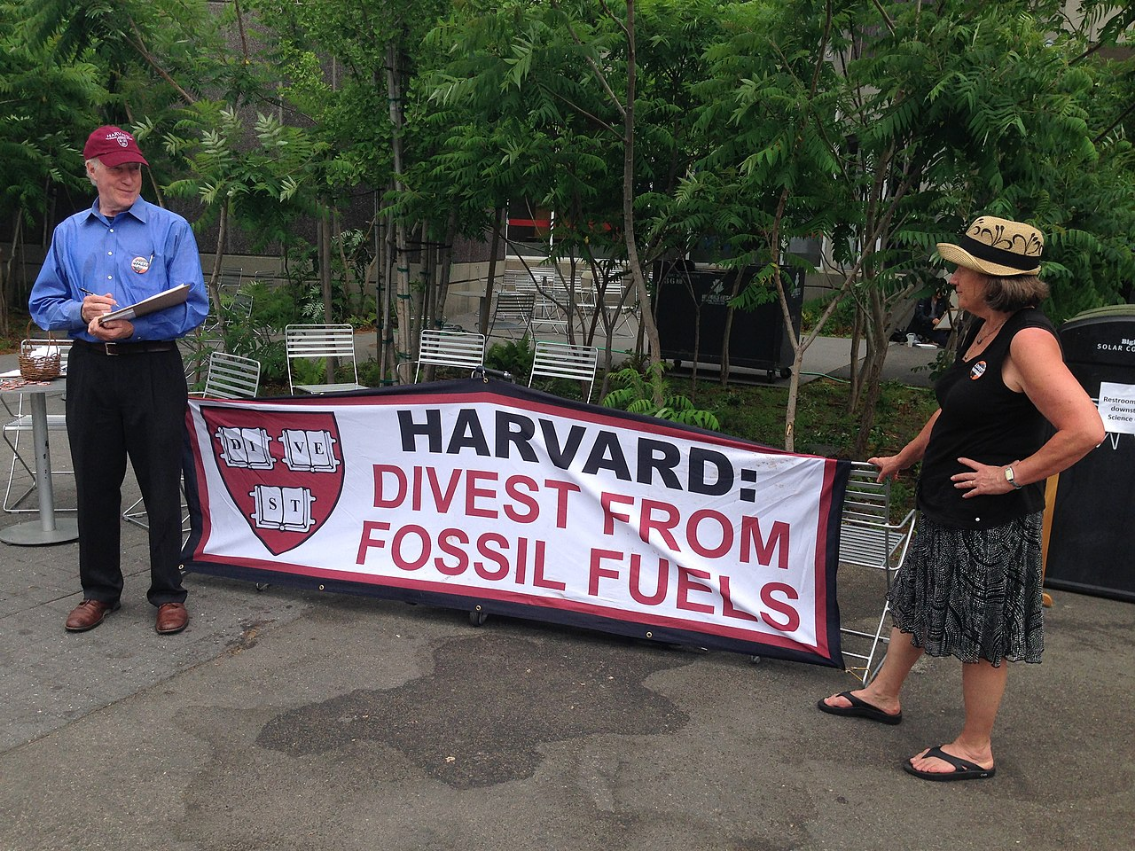

6.6. Divest Harvard

Divest Harvard is an organization at Harvard University that seeks to compel the university to divest from fossil fuel companies. The group was founded in 2012 by students at Harvard College.[68] In November 2012, a referendum on divestment passed at Harvard College with 72% support,[69] followed by a similar referendum at the Harvard Law School in May 2013, which passed with 67% support.[70][71] During this time, representatives from Divest Harvard began meeting with members of Harvard University's governing body, the Harvard Corporation,[72] but the meetings were described as unproductive.[73]

In October 2013, the Harvard Corporation formally announced that the university would not consider a policy of divestment.[74] Following this, Divest Harvard began organizing rallies, teach-ins,[75] and debates on divestment.[76] In March 2014, students from Divest Harvard recorded an impromptu exchange on divestment with Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust, during which Faust appeared to claim that fossil fuel companies do not block efforts to counteract climate change.[77] The video has since become a source of controversy.[78]

In April 2014, a group of nearly 100 Harvard faculty released an open letter to the Harvard Corporation arguing for divestment.[79] This was followed by a 30-hour blockade of the Harvard president's office by students protesting the president's refusal to engage in a public discussion of divestment; the Harvard administration terminated the blockade by arresting one of the student protesters.[80] Following the protest, Faust said she would not hold the open forum that students and faculty had requested and would not engage with students from Divest Harvard.[81] In May 2014, a group of Harvard alumni interrupted an alumni reunion event with Faust present by standing and holding a pro-divestment banner; the alumni were removed from the event and banned from Harvard's campus.[82]

In September 2014, Harvard faculty renewed their calls for an open forum on divestment[83] and continued to argue for divestment publicly.[84] In October 2014, Divest Harvard organized a three-day fast and public outreach event to call attention to the harms of climate change.[85] In November 2014, a group of students calling themselves the Harvard Climate Justice Coalition[86] filed a lawsuit against the Harvard Corporation to compel divestment on the grounds of Harvard's status as a non-profit organization.[87] The lawsuit was dismissed by a Massachusetts Superior Court judge, who wrote that "Plaintiffs have brought their advocacy, fervent and articulate and admirable as it is, to a forum that cannot grant the relief they seek."[88] The plaintiffs have stated that they plan to appeal the decision.

In January 2015, it was revealed that Harvard had increased its direct investments in fossil fuel companies considerably,[89] and the number of faculty and alumni supporting divestment grew. By April 2015, the faculty group calling for divestment grew to 250,[90] the Harvard alumni club of Vermont officially voted to endorse divestment,[90] and Divest Harvard announced the creation of a fossil-free alumni donation fund that Harvard would receive conditional on divestment.[91] In February 2015, Divest Harvard occupied the president's office for 24 hours in protest of the Harvard Corporation's continued unwillingness to engage students on the topic of divestment.[92] This was followed by an open letter from a group of prominent Harvard alumni urging the university to divest.[93] In April 2015, Divest Harvard and Harvard alumni carried out an announced[94] week-long protest called Harvard Heat Week,[95] which included rallies, marches, public outreach, and a continuous civil disobedience blockade of administrative buildings on campus.[96] The Harvard administration avoided engaging with the protest.[97] Following Heat Week, Divest Harvard carried out an unannounced one-day civil disobedience blockade of the Harvard president's office in protest of continued lack of action by the Harvard administration.[98]

In November 2019, at the annual Harvard-Yale football game, over 150 Harvard and Yale students stormed the field at halftime to demand divestment and the immediate cancellation of holdings in Puerto Rican debt, delaying the start of the second half by over 45 minutes.[99] The event was a joint protest led by Divest Harvard and Fossil Free Yale, and drew extensive coverage from news outlets and on social media, accompanied by the hashtag '#NobodyWins'.[100]

6.7. Fossil Free MIT

Fossil Free MIT (FFMIT) is a student organization at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology made up of MIT undergrads, graduate students, post-docs, faculty, staff and alumni.[101] The group was formed in Fall 2012 by six MIT students following a visit to Boston by Bill McKibben of 350.org on his "Do the Math" tour.[102] The group has collected over 3,500 signatures in a petition calling for MIT to (1) immediately freeze new investments in fossil fuel companies, and (2) divest within five years from current holdings in these companies.[103]

Following discussions with FFMIT, the university administration initiated a "campus-wide conversation" on climate change to take place from November 2014 to May 2015, which included the formation of the MIT Climate Change Conversation Committee.[104] The committee, composed of 13 faculty, staff, and students, was charged with engaging the MIT community to determine how the university could address climate change and with offering recommendations.[105] The conversation included solicitation of ideas and opinions of MIT community members, as well as a number of public events. The largest event was a fossil fuel divestment debate among six prominent voices on climate change that was attended by approximately 500 people.[105]

The committee released a report in June 2015, recommending a number of initiatives to be undertaken by the university. In regards to fossil fuel divestment, the committee "rejected the idea of blanket divestment from all fossil fuel companies"; although there was "support by (three-quarter) majority of the committee for targeted divestment from companies whose operations are heavily focused on the exploration for and/or extraction of the fossil fuels that are least compatible with mitigating climate change, for example coal and tar sands."[105]

Following the campus-wide conversation, on 21 October 2015, President L. Rafael Reif announced the MIT Plan for Action on Climate Change. While the plan enacted many of the committee's recommendations, the university administration chose not to divest its holdings in fossil fuel companies, stating that "divestment...is incompatible with the strategy of engagement with industry to solve problems that is at the heart of today’s plan."[106]

The following day, Fossil Free MIT began a sit-in outside the office of the President to protest the shortcomings of the plan, including the rejection of divestment.[107] Over 100 people overall participated in the sit-in, which received coverage by multiple news outlets, including the Boston Globe, Boston Magazine, and the Daily Caller.[108] The sit-in, which lasted 116 days, ended officially with an agreement with Vice President for Research Maria Zuber following negotiations about how to improve the Plan. The agreement did not include divestment, but succeeded in establishing a climate advisory committee and a climate ethics forum. In addition, the administration agreed to strengthen the university's carbon mitigation commitments, striving for carbon neutrality "as soon as possible."[109]

6.8. Faith Organizations

The biggest part of fossil fuel divestment commitments come from faith organizations - 350 from 1,300. On 18 May 2020, 42 faith organizations declared that they are divesting from fossil fuels. They called for a green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Catholic organisations with 40 billion dollars in assets joined Catholic Impact Investing Pledge.[110]

In 2020 the Catholic Church published a manual called "Journeying Towards Care For Our Common Home" that explains to Catholics how to divest from institutions considered to be harmful by the Catholic Church. Those include fossil fuels, child labour, and weapons. The Vatican Bank claims that it is not investing in fossil fuels with many other Catholic organisations. Pope Francis has called for climate action for many years. He published a call to stop the climate crisis named Laudato si'.[111]

7. Support for Fossil Fuel Divestment

7.1. Support for the Divestment Movement by Politicians and Individuals

| “ | It is clear the transition to a clean energy future is inevitable, beneficial and well underway, and that investors have a key role to play. | ” |

| — Ban Ki-moon, secretary-general of the United Nations (2016).[112] | ||

A number of individuals and organisations have voiced support for fossil fuel divestment including:

- Ban Ki-moon, secretary-general of the United Nations[112]

- Ed Davey

- Leonardo DiCaprio[113]

- Bianca Jagger

- Barack Obama

- Yotam Ottolenghi

- Tilda Swinton

In March 2015 Mary Robinson, Ban Ki-moon's special envoy on climate change and former Irish President stated, "it is almost a due diligence requirement to consider ending investment in dirty energy companies".[114]

Desmond Tutu has voiced support for fossil fuel divestment and compared it to divestment from South Africa in protest of apartheid.

We must stop climate change. And we can, if we use the tactics that worked in South Africa against the worst carbon emitters ... Throughout my life I have believed that the only just response to injustice is what Mahatma Gandhi termed "passive resistance". During the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, using boycotts, divestment and sanctions, and supported by our friends overseas, we were not only able to apply economic pressure on the unjust state, but also serious moral pressure.—Desmond Tutu[115]

In 2015, the London Assembly passed a motion calling on the Mayor of London to urgently divest pension funds from fossil fuel companies[116][117]

7.2. Support for the Divestment Movement by Investors

A prominent speaker at the 5th annual World Pensions & Investments Forum held in December 2015, Earth Institute Director Jeffrey Sachs voiced for institutional investors to take their fiduciary responsibility in reducing the risk of losses via fossil fuel divestment.[118]

7.3. Support for Specific Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaigns

Harvard University

In February 2015 alumni of Harvard University including Natalie Portman, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, Darren Aronofsky and Susan Faludi wrote an open letter to Harvard University demanding that it divest its $35.9 billion endowment from coal, gas, and oil companies.

Those students have done a remarkable job in garnering overwhelming student support for divestment, and the faculty too have delivered a strong message. But so far [Harvard] has not just refused to divest, they’ve doubled down by announcing the decision to buy stock in some of the dirtiest energy companies on the planet.—Open letter to Harvard university from notable alumni, 2014, [119]

Harvard's decision not to divest was explained in an open letter from the University President, Drew Faust:

Divestment is likely to have negligible financial impact on the affected companies. And such a strategy would diminish the influence or voice we might have with this industry. Divestment pits concerned citizens and institutions against companies that have enormous capacity and responsibility to promote progress toward a more sustainable future.[120]

University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow became the first university in Europe[3] to agree to divest from fossil fuels. The NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden commented:

I am proud to offer my support and endorsement for Climate Action Society’s fossil fuels divestment campaign. By confronting the threat of unsustainable energy use and exploration to our planetary habitat, the students of Glasgow University do a public service for all families of today and tomorrow.—Edward Snowden[121]

8. Companies That Investors Divest from

For a list of fossil fuel companies are the divestment campaigns' target, see List of oil exploration and production companies.

9. Groups Divesting or Taking Official Steps Toward Divestment by Country

9.1. United States

Governments and pension funds in the US

Governments and pension funds in the United States that have partially or completely divested, or that have taken steps toward divestment, include (listed alphabetically):

- Amherst, Cambridge, Northampton, Provincetown and Truro, Massachusetts – by 2014, city councils or town meetings in these municipalities passed resolutions calling on pension managers to divest from fossil fuels.[122]

- Ann Arbor, Michigan – in October 2013, after several rounds of consideration, the city council voted 9–2 to approve a nonbinding resolution requesting that the City of Ann Arbor Employees' Retirement System board cease new investments in the top 100 coal and top 100 gas and oil extraction companies and divest current such investments within five years.[123]

- Berkeley, California – in 2013, the City Council voted to adopt an official policy of divesting from city funds from direct ownership of publicly traded fossil-fuel companies; the city aims to complete the divestment process within the next five years.[124]

- Burlington, Vermont – in December 2014, the Burlington City Council unanimously approved conducting the study of possible divestment from major fossil-fuel companies. A task force of city councilors, retirement board members, public employee representatives and others was appointed to research the proposal and make recommendations for the city's retirement board within one year.[125]

- Eugene, Oregon – the City Council unanimously voted in January 2014 to take up the fossil-fuel issue at a future meeting.[126]

- Ithaca, New York – in 2013, Mayor Svante Myrick stated that the city did not have any investments in fossil fuels and would not make any such investment for as long as he was mayor. Myrick also encouraged the pension funds of the New York State and Local Retirement System, overseen by the Office of the New York State Comptroller, to divest.[127]

- Madison, Wisconsin – in July 2013, the city adopted a resolution declaring that it is the policy of the City of Madison not to invest in fossil-fuel companies. The resolution does not apply to the Madison Metropolitan School District (whose cash balances the city invests) or two municipal mutual insurance corporations of which the city is part-owner. Mayor Paul Soglin and the majority of city council members introduced the resolution.[128][129]

- New York City – in January 2018, New York City announced it will divest US$5 billion from fossil fuels interests over the next 5 years. In addition, the city is filing lawsuits against BP, ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Shell for costs the city faces in relation to climate change.[130]

- Providence, Rhode Island – in June 2013, the City Council voted 11–1 to enact a resolution directing the city's board of investment commissioners to divest from the world's largest coal, oil and gas companies within five years, and to not make any new investments in such firms.[131]

- San Francisco, California – in 2013, the Board of Supervisors unanimously passed nonbinding resolution urging managers of San Francisco Employees' Retirement System to divest from fossil fuels; in March 2015, the board of the retirement system voted to begin "level-two engagement", a step toward divestment.[132][133]

- Santa Monica, California – committed to divestment in 2013 and completed its divestment (of about $700,000) within one year.[134]

- Seattle, Washington – Mayor pledged to divest in 2012, but city and pension fund have not completed process.[135][136]

- Washington, D.C. – in June 2016, the City Council along with DC Divest announced that the District's $6.4 billion retirement fund had divested from direct holdings in the top 200 fossil fuel companies in the world.[137]

Colleges and universities in the US

Colleges and universities which have partially or completely divested, or which have taken steps toward divestment, include (listed alphabetically):

- American University ([[Washington, D.C.}})[138]

- Brevard College (Brevard, North Carolina, USA) – in February 2015, the college's board of trustees approved a resolution to divest the college's $25 million endowment from fossil fuels by 2018. At the time the decision was made, about $600,000 (4%) of the college's portfolio was invested in fossil fuels. The college became the first institution of higher education in the Southeastern United States to divest from fossil fuel.[139][140]

- California Institute of the Arts (Valencia, California, USA) – in December 2014, CalArts announced that it would immediately reduce the Institute's investments in fossil-fuel stocks by 25% (reallocating about $3.6 million in its portfolio) and would continue to not make direct investments in fossil fuel. The Institute also announced that it would "actively monitor the Institute's remaining carbon exposure and consider strategies that will continue to reduce the Institute's investments in fossil fuel companies, including seeking to eliminate exposure to the most carbon-intensive companies such as coal producers over the next five years."[141]

- California State University, Chico (Chico, California, USA) – in December 2014, the board of governors of the Chico State University Foundation, which manages the university's endowment, voted to change its investment policy and divest of holdings in fossil fuel companies. At the time the policy was adopted, the foundation had "no direct holdings in fossil-fuel companies and just under 2 percent of its portfolio in managed funds that include fossil fuel investments." The vote calls for excluding any direct investment in the top 200 fossil fuel companies and liquidating, within four years, all holdings in managed funds that include investments in fossil fuel companies.[142][143]

- College of the Atlantic (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) – in March 2013, the college's board of trustees voted to divest from fossil-fuel companies. About $1 million of the college's $30 million endowment was invested in such companies.[144]

- College of the Marshall Islands (Marshall Islands) – in December 2014 and January 2015, the college announced that its board of regents would be adopting a policy statement divising its small endowment (about $1 million) from fossil fuels.[145][146]

- Cornell University (Ithaca, New York, USA) – in May 2020, the Board of Trustees voted to divest from fossil fuels by instituting a moratorium on new private investment focused on fossil fuels. Investments are expected to grow in alternative and renewable energy portfolios. The committee's vote includes ending all current investments in fossil fuels over the next five to seven years. [147]

- Foothill–De Anza Community College District (Foothill College and De Anza College in Cupertino, California, USA) – the foundation's board of directors voted in October 2013 to divest from the top 200 fossil-fuel companies by June 2014, becoming the first community college foundation in the nation to commit to fossil-fuel divestment.[148][149]

- George Washington University (Washington, DC) – in June 2020, the college's board of trustees voted to divest from fossil fuels, which make up about 3% of the college's endowment.[150]

- Goddard College (Plainfield, Vermont, USA) – in January 2015, the college announced that it had completed its divestment, moving all of its endowment funds into fossil fuel-free accounts, becoming the third college in Vermont to do so.[151][152]

- Green Mountain College (Poultney, Vermont, USA) – in May 2013, the college's board of trustees approved immediate divestment from the top 200 publicly traded fossil-fuel companies. Such investments made up about 1% of the college's $3.1 million endowment.[153][154]

- Hampshire College (Amherst, Massachusetts, USA) – in December 2011, in the college's board of trustees approved a new environmental, social, and governance investing policy which called for "negligible fossil fuel holdings in our portfolio." The college announced in October 2012 that it had nearly completed the implementation of this policy.[155][156]

- Humboldt State University (Arcata, California, USA) – since at least 2004, the university has had no direct investments in fossil fuel-related industries.[157] In April 2014, the Humboldt State University Advancement Foundation, which oversees the university's endowment, unanimously adopted a new "environmentally responsible offset and mitigation policy" and "Humboldt Investment Pledge" to strictly limit its holdings in a variety of industries, including companies directly or indirectly involved in fossil fuels.[157][158] In October 2014, the foundation's board voted to shift 10% of its overall portfolio to "green funds" (funds with no holdings in fossil fuels or similar sectors) over the next year, reiterated its policy against direct investments in fossil fuels, and committed to creating a new fund invested entirely free of fossil fuels, with the distributions from the fund earmarked for campus-based sustainability projects.[158]

- Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, Maryland, USA) – in December 2017 the Board of trustees votes to eliminate investments in companies that produce coal for electric power as a major part of their business.[159]

- Lewis & Clark College (Portland, Oregon , USA) – in February 2018 the Board of trustees unanimously voted to divest from all fossil fuel holdings in the school endowment.[160]

- Middlebury College (Middlebury, Vermont, USA) – in January 2019, the board of trustees of Middlebury College unanimously voted to pass Energy2028, therefore agreeing to divest all direct holdings in the fossil fuel industry.[161] The plan defines these investments broadly, including "all those in enterprises whose core industry is oil and gas exploration and/or production, coal mining, oil and gas equipment, services and/or pipelines."[162] The vote came after years of organizing by the student-run Divest Middlebury campaign.[163]

- Pacific School of Religion (Berkeley, California, USA) – in February 2015, the seminary's board of trustees voted unanimously to divest the institution from the 200 largest fossil-fuel companies (those listed on the Carbon Tracker Initiative (CT200)).[164]

- San Francisco State University (San Francisco, California , USA) – in 2014, the San Francisco State University Foundation, which oversees the university's $51.2 million endowment, voted to make no new investments that would involve "direct ownership of companies with significant exposure to production or use of coal and tar sands." The foundation also voted to look into future divestment from all fossil-fuel companies.[165][166]

- Seattle University (Seattle, Washington, USA) - in September 2018, following student group preassure Seattle University is the first university in Washington state to divest its endowment of fossil fuels over the next five years. The action means that by 2023, Seattle University will no longer invest any of its $230 million endowment in the funds and securities of fossil-fuel companies. The university will work to achieve a 50 percent reduction by 31 December 2020, and expects to be fully divested by 30 June 2023. "The moral imperative for action is clear", said Seattle U President Stephen Sundborg in an announcement. "By taking this step we are acting boldly and making an important statement … We join with others also at the forefront of the growing divestment movement and hope our action encourages more to do the same". Seattle U also becomes the first among the nation's 28 Jesuit colleges and universities to divest. "It’s definitely a victory for us", said student Connor Crinion, a member of Sustainable Student Action, the student group that has pushed for divestment since 2012. "We’re hoping this might be a milestone" that will encourage divestment at other schools in Washington, as well as at other Jesuit universities, he said [1].

- Stanford University (Stanford, California, USA) – in May 2014, following an advisory panel's recommendation, the university's board of trustees voted to divest the investment portfolio of its $18.7 billion endowment of companies "whose principal business is coal." This made Stanford the "first major university to lend support to a nationwide campaign to purge endowments and pension funds of fossil fuel investments."[167][168]

- Sterling College (Craftsbury, Vermont, USA) – the tiny college's board of trustees voted in February 2013 to divest from the top 200 fossil-fuel companies. The college announced that it had completed divestment of its $920,000 endowment by July 2013, with all of its investments in a fossil-fuel free portfolio.[169][170]

- The New School (New York, New York, USA) – in February 2015, the New School announced that it would divest from all fossil-fuel investments in coming years. The school simultaneously announced that "it is also reshaping the entire curriculum to focus more on climate change and sustainability."[171]

- Unity College (Unity, Maine, USA) – in 2008, the college's board of trustees asked its endowment-management firm to begin decreasing its exposure to large energy companies (which then made up about 10% of its portfolio). In November 2012, the board of trustees unanimously voted to divest the remainder of its fossil-fuel holdings (then about 3% of its portfolio) over the next five years.[172][173] The college completed divestment in 2014, three years ahead of schedule.[174] Unity College was the first institution of higher education in the United States to divest from fossil fuels.[173][175]

- University of California (Oakland, California, USA) – In September 2019, the University of California announced it will divest its $83 billion in endowment and pension funds from the fossil fuel industry, citing 'financial risk'.[176]

- University of Dayton (Dayton, Ohio, USA) – In May 2014, the University of Dayton's board of trustees unanimously approved a plan to begin to divest the university's holdings from the top 200 fossil-fuel companies. At the time of the announcement, about 5% ($35 million) of the university's $670 million investment pool was held in such companies. UD became the first Catholic university in the US to divest from fossil fuels. The plan was publicly announced in June 2014.[177][178] The university planned to review its progress in 18 months.[179]

- University of Maine System (Maine, USA) – in January 2015, the board of trustees of the University of Maine System unanimously voted to divest from direct holdings in coal-mining companies. The system's total investments were about $589 million; the decision would affect $502,000 of direct investments in coal, which amounts to about 30% of the system's total ($1.7 million exposure to coal, including both direct and indirect investments). Some board members stated that they would continue to consider full system-wide divestment in the future. Separately, the University of Maine at Presque Isle, one of seven schools within the system, announced that its own foundation had divested from all fossil-fuel investments.[180]

- University of Massachusetts (Massachusetts , USA) – in December 2015, the board of trustees of the University of Massachusetts System announced their plans to divest from direct holdings in coal companies. Once this decision was released, the escalation of a four-year student-run campaign, the UMass Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaign, occurred. A 500 student week long occupation of the Whitmore Administration Building led to 34 student arrests and a decision to vote on fossil fuel divestment at the next Board of Trustees Meeting. On 25 May 2016 it was announced the University of Massachusetts system would divest its endowment from direct holdings in fossil fuels, becoming the first major public university to do so.[181]

Foundations and charitable endowments in the US

We see this as both a moral imperative and an economic opportunity.

— Stephen Heintz, president of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund,

on disinvesting from fossil fuels, 30 September 2014[182]

In September 2014, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund announced it would be divesting its fossil fuel investments totalling $60 million. "We are quite convinced that if he were alive today, as an astute businessman looking out to the future, he would be moving out of fossil fuels and investing in clean, renewable energy."[183]

Religious organizations in the US

The 2013 general synod of the United Church of Christ (UCC) passed a resolution (sponsored by the Massachusetts Conference and ten other conferences of the UCC) outlining a path to divestment of church funds from fossil-fuel holdings. Under the resolution, a plan for divestment will be developed by June 2018. The original proposal considered by the general synod called for a five-year plan to divestment; this was changed following negotiations between divestment proponents and the UCC's investment arm, United Church Funds.[184][185][186] United Church Funds also established a denominational fossil-free fund (believed to be the first of its kind), which raised almost $16 million from UCC congregations, conferences, and other groups by late September 2014.[186]

In June 2014, the trustees of Union Theological Seminary in New York City unanimously voted to begin divesting fossil fuels from the seminary's $108.4 million endowment.[187]

Banks in the US

In 2019 the Goldman Sachs bank divested from arctic oil, coal thermal mines and mountaintop removal projects[188]

9.2. United Kingdom

Local Authorities in the UK

The UK government has explicitly warned Local Authorities in the UK that they may be penalised if they boycott suppliers on the basis of involvement in fossil fuel extraction so long as it remains government policy not to boycott. [189] This makes it challenging for local government to act on boycott even if it believes it has an ethical or environmental case to do so.

Colleges and universities in the UK

- SOAS, University of London (London, United Kingdom) – in March 2015, SOAS announced it will divest within 3 years. SOAS fulfilled this pledge in 2018.[190] SOAS was the first university in London to divest and one of the first in the UK. Its announcement came after a long running student-led campaign.[191]

- King's College London (London, United Kingdom) – in September 2016, King's College London agreed to invest 15% of its £179 million endowment in clean energy and to drop investments in the most polluting fossil fuels. The university currently has exposure to Anglo American, Rio Tinto, and Glencore.[192]

- University of Glasgow (Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom) – in October 2014, the university announced plans to freeze new investments in fossil fuels and divest from fossil fuel companies over the next ten years. Hydrocarbon investment made up around 4% of the university's total endowment; about £18 million in such investments will be withdrawn over the decade-long phaseout. The University of Glasgow was the first university in Europe to divest from fossil fuels.[193][194]

- University of Bedfordshire (Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire, England , United Kingdom) – in January 2015, decided to formalize its previously informal decision "not to invest in specific sectors such as fossil fuels."[195]

- University of Bristol (United Kingdom)) – a long campaign to make Bristol University divest from fossil fuels took a major step when Carla Denyer, a Bristol Green Party councillor sitting on one of the University's governance bodies, tabled a divestment motion in November 2015.[196][197] Despite initial defeats,[198] the campaign succeeded in March 2017.[199][200]t

As of January 2020, according to student campaigning organisation People & Planet, over half of UK universities have now made some form of divestment commitment, pushing the UK further education divestment total above £12 billion.[201]

Religious organizations in the UK

On 30 April 2015, the Church of England agreed to divest £12 million from its tar sands oil and thermal coal holdings. The church has a £9 billion investment fund.[202]

9.3. New Zealand

Colleges and universities in New Zealand

- University of Otago (Dunedin, New Zealand) – in September 2016, the university created an ethical investments policy excluding investment in 'the exploration and extraction of fossil fuels'. The University of Otago was the second university in New Zealand to commit to fossil free investing.[203]

- Victoria University (Wellington, New Zealand) – in December 2014, the university announced its intention to divest all its investments from fossil fuels, becoming the first New Zealand university to do so.[204]

9.4. Republic of Ireland

Governments and pension funds in Ireland

Ireland is to be the world's first country to divest public money from fossil fuels.[205] Other sources.[206][207]

9.5. Sweden

Governments and pension funds in Sweden

- Municipality of Örebro — "The City of Örebro is the first Swedish city to commit to pull its funds out of fossil fuels, in a move to align its investments with its environmental goals. Örebro is the 30th local authority worldwide to take this step, following in the footsteps of cities such as San Francisco, Seattle and the Dutch town of Boxtel.[208]

Colleges and universities in Sweden

- Chalmers University of Technology (Göteborg, Sweden) – in early 2015, the university became the first Swedish university to divest from fossil fuels. The university said it would sell about $600,000 in fossil-fuel holdings.[209]

9.6. EU

European Investment Bank

In November 2019, the European Investment Bank (EIB), the world's largest international public lending institution, adopted a strategy to end funding for new, unabated fossil fuel energy projects, including natural gas, from the end of 2021.[210][211]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Earth:Fossil_fuel_divestment

References

- Clark, Duncan. "How much of the world's fossil fuel can we burn?". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/keep-it-in-the-ground-blog/2015/mar/25/what-numbers-tell-about-how-much-fossil-fuel-reserves-cant-burn. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- EPA,OAR,OAP,CCD, US. "Climate Change: Basic Information" (in en). https://www.epa.gov/climatechange/climate-change-basic-information.

- "Fossil fuel divestment: a brief history". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/oct/08/fossil-fuel-divestment-a-brief-history. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Paris Agreement (article 2, page 22), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (page visited on 2 November 2016) http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

- Franta, Benjamin A. (8 February 2016). "On Divestment, Adopt the Toronto Principle". Harvard Crimson. http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2016/2/8/franta-divestment-toronto-principle/.

- "The Fossil Fuel Industry and the Case for Divestment". The Asquith Press at the Toronto Reference Library. 10 April 2015. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/to350/pages/50/attachments/original/1428958642/fossil-fuel-divest-new.pdf?1428958642.

- Karney, Brian (15 December 2015). "Report of the President's Advisory Committee on Divestment from Fossil Fuels". University of Toronto. http://www.president.utoronto.ca/secure-content/uploads/2015/12/Report-of-the-Advisory-Committee-on-Divestment-from-Fossil-Fuels-December-2015.pdf.

- "Measuring the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement, September 2014". Arabella Advisors. http://www.arabellaadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Measuring-the-Global-Divestment-Movement.pdf. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Harvey, Fiona (6 March 2014). "'Carbon bubble' poses serious threat to UK economy, MPs warn". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/06/carbon-bubble-threat-uk-economy-fossil-fuels-mps. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Dickinson, Tim. "The Logic of Divestment: Why We Have to Kiss Off Big Carbon Now". Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-logic-of-divestment-why-we-have-to-kiss-off-big-carbon-20150114. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Shankleman, Jessica. "Mark Carney: most fossil fuel reserves can't be burned". https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/oct/13/mark-carney-fossil-fuel-reserves-burned-carbon-bubble. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Partington, Richard (15 October 2019). "Bank of England boss says global finance is funding 4C temperature rise" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/oct/15/bank-of-england-boss-warns-global-finance-it-is-funding-climate-crisis.

- Carrington, Damian (13 October 2019). "Firms ignoring climate crisis will go bankrupt, says Mark Carney" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/13/firms-ignoring-climate-crisis-bankrupt-mark-carney-bank-england-governor.

- "World Energy Investment Outlook – Special Report". International Energy Agency. 3 June 2014. p. 43. http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/investment/. Retrieved 30 March 2015. The report estimated that about $120 billion of new fossil-fuel capacity in the power sector would be idled before repaying its investment costs, along with about $130 billion of stranded exploration costs for oil and about $50 billion for gas.

- "US coal sector in 'structural decline', financial analysts say". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/24/us-coal-sector-in-terminal-decline-financial-analysts-say. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Carrington, Damian. "Leave fossil fuels buried to prevent climate change, study urges". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jan/07/much-worlds-fossil-fuel-reserve-must-stay-buried-prevent-climate-change-study-says. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Hope, Chris; Gilding, Paul; Alvarez, Jimena (2015). Quantifying the implicit climate subsidy received by leading fossil fuel companies — Working Paper No. 02/2015. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge. http://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/research/workingpapers/wp1502.pdf. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Measuring fossil fuel 'hidden' costs". 23 July 2015. http://insight.jbs.cam.ac.uk/2015/measuring-fossil-fuel-hidden-costs/.

- "Fossil fuels face $30 trillion losses from climate, renewables". Reneweconomy. 28 April 2014. http://reneweconomy.com.au/2014/28-trillion-11465.

- "Stranded assets, fossilised revenues". Kepler Cheuvreux. 24 April 2014. http://www.keplercheuvreux.com/pdf/research/EG_EG_253208.pdf.

- Ambrose, Jillian (14 October 2019). "Rise of renewables may see off oil firms decades earlier than they think" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/14/rise-renewables-oil-firms-decades-earlier-think.

- Parkinson, Giles. "Solar has won. Even if coal were free to burn, power stations couldn't compete". https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/07/solar-has-won-even-if-coal-were-free-to-burn-power-stations-couldnt-compete. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Solar at grid parity in most of world by 2017". http://reneweconomy.com.au/2015/solar-grid-parity-world-2017. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Breakdown of Electricity Generation by Energy Source". The Shift Project. http://www.tsp-data-portal.org/Breakdown-of-Electricity-Generation-by-Energy-Source#tspQvChart. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Stanwell blames solar for decline in fossil fuel baseload". http://reneweconomy.com.au/2013/stanwell-blames-solar-for-decline-in-fossil-fuel-baseload-54543. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Atif Ansar, Ben Caldecott and James Tilbury, [ "Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: what does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets?"], University of Oxford, 11 March 2015 (page visited on 20 September 2016).

- Geddes, Patrick. "Do the Investment Math: Building a Carbon-Free Portfolio". Aperio Group. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130203053752/http://www.aperiogroup.com/system/files/documents/building_a_carbon_free_portfolio.pdf.

- Sanzillo, Tom; Hipple, Kathy. "Fossil Fuel Investments: Looking Backwards May Prove Costly to Investors in Today’s Market". IEEFA. https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Divestment-Brief-February-2019.pdf.

- John Schwartz, Harvard Students Move Fossil Fuel Stock Fight to Court, New York Times (19 November 2014). https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/20/us/harvard-students-move-fossil-fuel-divestment-fight-to-court.html

- Mariel A. Klein & Theodore R. Delwiche, Judge Dismisses Divestment Lawsuit, Harvard Crimson (24 March 2015). http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2015/3/24/judge-dismisses-divestment-lawsuit/

- Chuck Quirmbach, American Petroleum Institute Economist: Efforts to Divest From Fossil Fuels 'Disgust' Him, Wisconsin Public Radio (4 March 2014). http://www.wpr.org/american-petroleum-institute-economist-efforts-divest-fossil-fuels-disgust-him

- Benjamin Sporton (2015). "The High Cost of Divestment". 3. Cornerstone, The Official Journal of the World Coal Industry. pp. 8–11. http://cornerstonemag.net/the-high-cost-of-divestment/.

- "Measuring the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement, September 2015". Arabella Advisors. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160323091725/http://www.arabellaadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Measuring-the-Growth-of-the-Divestment-Movement.pdf. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- "Fossil Free, Divestment Commitments, April 2016". http://gofossilfree.org/commitments. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- {}

- "About Us". http://www.anuenviro.org/values/.

- "ANU to sell coal seam gas shares after student pressure" (in en-AU). http://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2011/10/13/3338652.htm.

- "ANU Removes Itself From Coal Seam Gas Operations | Woroni". http://dev.woroni.com.au/articles/news/anu-removes-itself-coal-seam-gas-operations.

- "Metgasco Our Dirty Secret" (in en-US). http://www.woroni.com.au/news/metgasco-our-dirty-secret/.

- "ANU Investments in Fossil Fuels – a Freedom of Information request to Australian National University – Right To Know". https://www.righttoknow.org.au/request/anu_investments_in_fossil_fuels.

- "ANU students lukewarm on 'gold standard' policy". http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/anu-students-lukewarm-on-gold-standard-policy-20131007-2v3e4.html.

- Klee, Louis (23 October 2014). "Students put the Coalition on notice over climate change". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/comment/students-put-the-coalition-on-notice-over-climate-change-20141022-119sn7.html.

- "ANU sale of fossil fuel holdings not enough: students" (in en-AU). http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-10-03/anu-selling-fossil-fuel-company-holdings-not-enough-student-says/5789748.

- "ANU investment policy draws fire". http://www.canberratimes.com.au/comment/ct-editorial/anu-investment-policy-draws-fire-20141007-10r8pu.html.

- Milman, Oliver (12 October 2014). "Coalition accused of 'bullying' ANU after criticism of fossil fuel divestment" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/oct/13/coalition-accused-of-bullying-anu-after-criticism-of-fossil-fuel-divestment.

- "Pyne says ANU decision to ditch mining shares 'bizarre'" (in en-AU). http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-10-13/pyne-says-anu-decision-to-ditch-mining-companies-bizarre/5808674.

- "Tony Abbott attacks ANU's 'stupid decision' to dump fossil fuel investments". https://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/tony-abbott-attacks-anus-stupid-decision-to-dump-fossil-fuel-investments-20141015-116a0y.html.

- Young, Ian (17 December 2015). "Farewell ANU". http://vcdesk.anu.edu.au/2015/12/17/farewell-anu/.

- Taylor, Lenore; editor, political (17 October 2014). "ANU fossil fuel divestment furore proves movement is no sideshow" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/oct/17/anu-fossil-fuel-divestment-furore-proves-movement-is-no-sideshow.

- Divest-Invest Philanthropy ("Divest from fossil fuels. Invest in climate solutions."), official website (page visited on 7 August 2016). http://divestinvest.org

- The two divestment organisations cited by Tim Flannery in his list of "Organisations fighting for a better climate" are 350.org and Divest-Invest Philanthropy. Reference: Tim Flannery, Atmosphere of Hope. Solutions to the Climate Crisis, Penguin Books, 2015, pages 224–225 (ISBN:9780141981048).

- "Keep it in the Ground campaign: six things we've learned". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/keep-it-in-the-ground-blog/2015/mar/25/keep-it-in-the-ground-campaign-six-things-weve-learned. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Keep it in the ground". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ng-interactive/2015/mar/16/keep-it-in-the-ground-guardian-climate-change-campaign. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/jan/29/guardian-to-ban-advertising-from-fossil-fuel-firms-climate-crisis

- Wines, Michael (6 May 2014). "Stanford to Purge $18 Billion Endowment of Coal Stock". https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/07/education/stanford-to-purge-18-billion-endowment-of-coal-stock.html. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "This Changes Everything – The Book". https://thischangeseverything.org/book/. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "2014 ASSU Spring Quarter General Election Results". http://elections.stanford.edu/archives/2014-elections-results. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Wayback Machine". 7 June 2018. http://www.fossilfreestanford.org/uploads/2/3/4/0/23400882/ugs-s2013-14.pdf. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Wayback Machine". 7 June 2018. http://www.fossilfreestanford.org/uploads/2/3/4/0/23400882/gsc-2014-21__1_.pdf. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Ed, Op (11 May 2016). "ASSU Execs call for Board to represent student consensus on fossil fuel divestment". https://www.stanforddaily.com/2016/05/10/assu-execs-call-for-board-to-represent-student-consensus-on-fossil-fuel-divestment/. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Goldenberg, Suzanne; correspondent, US environment (11 January 2015). "Stanford professors urge withdrawal from fossil fuel investments". https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jan/11/stanford-professors-fossil-fuel-investments. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Stanford Faculty For Fossil Fuel Divestment – Join Us". 8 September 2018. http://www.stanfordfacultydivest.org/. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Letter – Stanford Faculty For Fossil Fuel Divestment". 8 September 2018. http://www.stanfordfacultydivest.org/letter.html. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "SIT-IN: RECAP – Fossil Free Stanford". 21 March 2017. http://www.fossilfreestanford.org/sit-in-recap.html. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Sit-in at Stanford's Main Quad ends, and protesters call meeting with university president 'disappointing'". 20 November 2015. https://www.mercurynews.com/2015/11/20/sit-in-at-stanfords-main-quad-ends-and-protesters-call-meeting-with-university-president-disappointing/. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- University, Stanford (28 October 2015). "Stanford issues statement on climate change ahead of Paris conference". https://news.stanford.edu/2015/10/28/climate-change-statement-102815/. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Service, Bay City News (12 June 2016). "Students, alumni pledge to withhold donations until university divests from fossil fuels". https://www.sfgate.com/news/bayarea/article/Students-And-Alumni-Pledge-To-Withhold-Donations-8079241.php. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Arrested Divestment | Magazine | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2014/10/2/arrested-divestment-magazine/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Welton, Alli (20 November 2012). "Harvard Students Vote 72 Percent Support for Fossil Fuel Divestment". The Nation. http://www.thenation.com/article/harvard-students-vote-72-percent-support-fossil-fuel-divestment/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Lee, Steven S.. "Law School Students Vote for Divestment | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2013/5/8/law-school-vote-divestment/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Patel, Dev A.. "HLS Student Government Sends Pro-Divestment Letters to Minow, Faust | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2013/11/18/HLS-divestment-letter-government/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Smith, Randall (5 September 2013). "A New Divestment Focus on Campus: Fossil Fuels". The New York Times. https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/09/05/a-new-divestment-focus-fossil-fuels/.

- Raghuveer, Tara (20 April 2015). "Former Undergraduate Council President: What Happened Behind Divest Harvard Closed Doors". Time. http://time.com/3825978/divest-harvard-closed-doors/.

- "Fossil Fuel Divestment Statement | Harvard University". 3 October 2013. http://www.harvard.edu/president/fossil-fuels. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Jessica Leber (1 October 2013). "Can The Growing Student Movement To Divest Colleges From Fossil Fuels Succeed? | Co.Exist | ideas + impact". http://www.fastcoexist.com/3018395/can-the-growing-student-movement-to-divest-colleges-from-fossil-fuels-succeed. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Bernhard, Meg P.. "Forum Debates University Divestment | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2013/11/10/divest-harvard-forum-investment/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Romm, Joe (4 March 2014). "Exclusive: Harvard President Faust Says Fossil Fuel Companies Are Not Blocking Clean Energy". ThinkProgress. http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2014/03/04/3361911/harvard-president-faust-fossil-fuel/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Hashmi, Amna H.. "Faust Expresses Disappointment in Divest Harvard Video Confrontation | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2014/3/11/faust-disappointed-divest-harvard/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- McDonald, Michael (10 April 2014). "Harvard Faculty Urges University to Divest From Fossil Fuels". Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-04-10/harvard-faculty-urges-university-to-divest-from-fossil-fuels.

- Crooks, Ed (1 May 2014). "Fossil fuel protesters blockade offices at Harvard University". http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/f9a93dfc-d13e-11e3-bdbb-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3gq0ySrYf. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Watros, Steven R.. "Faust Says She Will Work with Faculty, Not Divest Group, To Discuss Climate Change | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2014/5/8/faust-divestment-talk-faculty/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Ducharme, Jamie (30 May 2014). "Harvard Alumni Stage Protest During Reunion Ceremony". http://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/blog/2014/05/30/distinguished-harvard-alumni-stage-protest-reunion-ceremony/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Patel, Dev A.. "Faculty for Divestment Renew Call for Open Forum | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2014/9/11/faculty-renew-divestment-call/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Harvard faculty for divestment hold public forum, meet privately with Faust". Harvard Magazine. http://harvardmagazine.com/2014/10/faculty-members-make-the-case-for-divestment. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Delwiche, Theodore R.. "Activists Kick Off Week-Long Fast for Divestment | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2014/10/21/divest-harvard-week-fast/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Harvard Climate Justice Coalition v. President and Fellows of Harvard College | A student lawsuit to enjoin the Harvard Corporation's investments in fossil fuel companies". http://www.divestproject.org/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Schwartz, John (19 November 2014). "Harvard Students Move Fossil Fuel Stock Fight to Court". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/20/us/harvard-students-move-fossil-fuel-divestment-fight-to-court.html.

- Delwiche, Theodore R.. "Judge Dismisses Divestment Lawsuit | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2015/3/24/judge-dismisses-divestment-lawsuit/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Suzanne Goldenberg. "Harvard defies divestment campaigners and invests tens of millions of dollars in fossil fuels | Environment". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jan/14/harvard-invests-tens-millions-dollars-fossil-fuels-face-divestment-campaign. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Delwiche, Theodore R.. "Vermont Harvard Club Endorses Divestment | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2014/12/25/vermont-harvard-club-endorses-divestment/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Jessica Leber (19 February 2015). "The Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement's Newest Strategy: Alternative Endowments | Co.Exist | ideas + impact". http://www.fastcoexist.com/3043781/the-fossil-fuel-divestment-movements-newest-strategy-alternative-endowments. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Delwiche, Theodore R.. "Faust Disapproves of Divest Harvard's February Occupation | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2015/3/30/faust-disapproves-divest-occupation/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Matt Rocheleau (20 February 2015). "Alumni withhold donations, join student protests to pressure colleges to divest from fossil fuels". The Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/02/19/alumni-withhold-donations-join-student-protests-pressure-colleges-divest-from-fossil-fuels/WgWZ1SQKEAxigN6Gl1pRrI/story.html. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Emma Howard. "Harvard divestment campaigners gear up for a week of action | Environment". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/apr/13/harvard-divestment-campaigners-gear-up-for-a-week-of-action. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Harvard Heat Week – Wrap up". http://harvardheatweek.org/wrap-up/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Nicky Woolf. "Cornel West warns of 'Planetary Selma' at Harvard fossil fuel divestment protest | Environment". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/apr/17/harvard-divestment-protest-civil-rights-moment. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Klein, Mariel A.. "Harvard Leaders Stay Quiet on Divest, Even During 'Heat Week' | News | The Harvard Crimson". http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2015/4/17/administration-response-divest-harvard/. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Steve Annear (13 May 2015). "Harvard students block doorway to school building in protest". The Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/05/13/harvard-students-block-doorway-school-building-protest/ezlByngZrjWZ8TpJkfCyRI/story.html. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Yale-Harvard football game disrupted by climate protesters storming field" (in en). https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/yale-harvard-football-game-interrupted-climate-protesters-storming-field-n1090166.

- "Washington Examiner". https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/nobody-wins-climate-protesters-disrupt-harvard-yale-football-game.