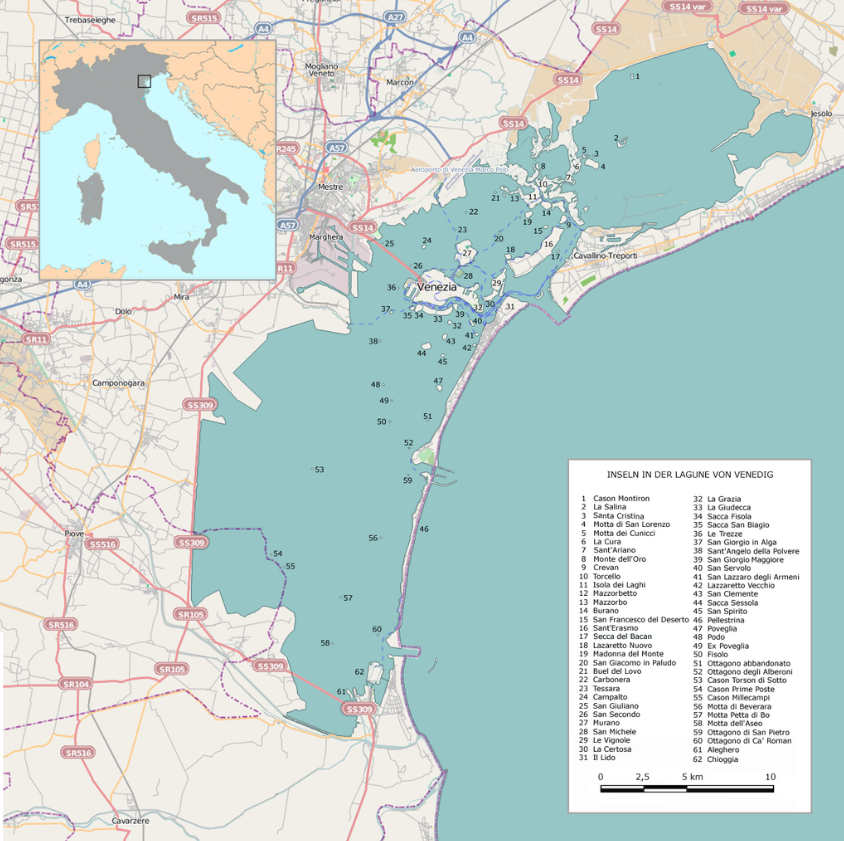

MOSE (MOdulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, Experimental Electromechanical Module) is a project intended to protect the city of Venice, Italy, and the Venetian Lagoon from flooding. The project is an integrated system consisting of rows of mobile gates installed at the Lido, Malamocco, and Chioggia inlets that are able to isolate the Venetian Lagoon temporarily from the Adriatic Sea during acqua alta high tides. Together with other measures, such as coastal reinforcement, the raising of quaysides, and the paving and improvement of the lagoon, MOSE is designed to protect Venice and the lagoon from tides of up to 3 metres (9.8 ft). The Consorzio Venezia Nuova is responsible for the work on behalf of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport – Venice Water Authority. Construction began simultaneously in 2003. On 10 July 2020, the first full test was successfully completed, and after multiple delays, cost overruns, and scandals resulted in the project missing its 2018 completion deadline (originally a 2011 deadline) it is now expected to be fully completed by the end of 2021.

- elettromeccanico

- electromechanical

- venice

1. Origin of the Name

Before the acronym was used to describe the entire flood protection system, MOSE referred to the 1:1 scale prototype of a gate that had been tested between 1988 and 1992 at the Lido inlet.

The name also holds a secondary meaning: "MOSE" alludes to the biblical character Moses ("Mosè" in Italian), who is remembered for parting the Red Sea.

2. Context

MOSE is part of a General Plan of Interventions to safeguard Venice and the lagoon. The project was begun in 1987 by the Ministry of Infrastructure through the Venice Water Authority (the Ministry's operational arm in the lagoon) and the concessionary Consorzio Venezia Nuova. The measures already completed or underway along the coastline and in the lagoon are the most important environmental defense, restoration, and improvement program ever implemented by the Italian State.

In parallel with the construction of MOSE, the Venice Water Authority and Venice Local Authority are raising quaysides and paving in the city in order to protect built-up areas in the lagoon from medium high tides (below 110 centimetres (43 in), the height at which the mobile barriers will come into operation). These measures are extremely complex, particularly in urban settings such as Venice and Chioggia where the raising must take account of the delicate architectural and monumental context. Measures to improve the shallow lagoon environment are aimed at slowing degradation of the morphological structures caused by subsidence, eustatism, and erosion due to waves and wash. Work is underway throughout the lagoon basin to protect, reconstruct, and renaturalise salt marshes, mud flats and shallows; restore the environment of the smaller islands; and dredge lagoon canals and channels.

Important activities are also underway to redress pollution in the industrial area of Porto Marghera, at the edge of the central lagoon. Islands formerly used as rubbish dumps are being secured while industrial canals are being consolidated and sealed after removal of their polluted sediments.

3. Objectives

The aim of MOSE is to protect the lagoon, its towns, villages and inhabitants along with its iconic historic, artistic and environmental heritage from floods, including extreme events. Although the tide in the lagoon basin is lower than in other areas of the world (where it may reach as high as 20 metres (66 ft)), the phenomenon may become significant when associated with atmospheric and meteorological factors such as low pressure and the bora, a north-easterly wind coming from Trieste, or the Sirocco, a hot south-easterly wind. Those conditions push waves into the gulf of Venice. High water is also worsened by rain and water flowing into the lagoon from the drainage basin at 36 inflow points associated with small rivers and canals.

Floods have caused damage since ancient times and have become ever more frequent and intense as a result of the combined effect of eustatism (a rise in sea level) and subsidence (a drop in land level) caused by natural and man-induced phenomena. Today, towns and villages in the lagoon are an average of 23 centimetres (9.1 in) lower with respect to the water level than at the beginning of the 1900s and each year, thousands of floods cause serious problems for the inhabitants as well as deterioration of architecture, urban structures and the ecosystem. Over the entire lagoon area, there is also a constant risk of an extreme catastrophic event such as that of 4 November 1966 (the great flood) when a tide of 194 centimetres (76 in) submerged Venice, Chioggia and the other built-up areas. Floods effects are exacerbated due to greater erosion by the sea caused by human interventions to facilitate port activities (e.g. through the construction of jetties and artificial canals); establishment of the industrial Porto Marghera area; and increased wash from motorized boats, which all aggravate erosion of morphological structures and the foundations of quaysides and buildings. In the future, the high water phenomenon may be further aggravated by the predicted rise in sea level as a result of global warming.

In this context, MOSE, together with reinforcement of the barrier island, has been designed to provide protection from tides of up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) in height. The aim of MOSE is to protect the lagoon, even if the most pessimistic hypotheses are proven true, such as a rise in sea level of at least 60 centimetres (24 in). However, the reports have grown more pessimistic with time compared to when MOSE was originally planned; the 2019 estimate from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) predicts a rise in sea level of between 60 and 110 centimetres (24 and 43 in) by 2100 if emissions continue to increase, which MOSE was not designed to handle.[1]

MOSE is flexible and can be operated in different ways according to the characteristics and height of the tide. Given that the gates are independent and can be operated separately, all three inlets can be closed in the case of an exceptional event, the inlets can be closed one at a time according to the winds, atmospheric pressure and height of tide forecast, or again, each inlet can be partially closed.

Exceptionally high waters have struck the city since 1935: levels of 140cm or greater have been recorded during the following floods, with 12 of the 20 events occurring in the 21st century:

| Date | Height |

|---|---|

| 1966 (4 November) | (194 centimetres (76 in)), |

| 2019 (12 November) | (187 centimetres (74 in)),[2] |

| 1979 (22 December) | (166 centimetres (65 in)), |

| 1986 (1 February) | (159 centimetres (63 in)), |

| 2018 (29 October) | (156 centimetres (61 in)), |

| 2008 (1 December) | (156 centimetres (61 in)), |

| 2019 (15 November) | (154 centimetres (61 in)), |

| 1951 (15 November) | (151 centimetres (59 in)), |

| 2012 (11 November) | (149 centimetres (59 in)), |

| 1936 (16 April) | (147 centimetres (58 in)), |

| 2002 (16 November) | (147 centimetres (58 in)), |

| 2009 (25 December) | (145 centimetres (57 in)), |

| 1960 (15 October) | (145 centimetres (57 in)), |

| 2019 (13 November) | (144 centimetres (57 in)), |

| 2009 (23 December) | (144 centimetres (57 in)), |

| 2000 (6 November) | (144 centimetres (57 in)), |

| 2013 (12 February) | (143 centimetres (56 in)), |

| 2012 (1 November) | (143 centimetres (56 in)), |

| 1992 (8 December) | (142 centimetres (56 in)), |

| 1979 (17 February) | (140 centimetres (55 in)). |

Prior to 1936, the highest levels had been in 1879, when on 25 February the water reached 137.5cm, and on 21 November 1916, when a level of 136cm occurred. Since 1936, there have been 17 occasions when the level reached between 130 and 140cm.

All values were recorded at the monitoring station at Punta della Salute (Punta della Dogana) and refer to the 1897 tidal datum point.[3]

The highest tide in over five decades on 13 November 2019 left 85% of the city flooded. Mayor Luigi Brugnaro blamed the situation on climate change. A Washington Post report provided a more thorough analysis:[4]

"The sea level has been rising even more rapidly in Venice than in other parts of the world. At the same time, the city is sinking, the result of tectonic plates shifting below the Italian coast. Those factors together, along with the more frequent extreme weather events associated with climate change, contribute to floods."

4. Chronology

Following the flood of 4 November 1966 when Venice, Chioggia and the other built-up areas in the lagoon were submerged by a tide of 194 centimetres (76 in), the first Special Law for Venice declared the problem of safeguarding the city to be of "priority national interest".[5] This marked the beginning of a long legislative and technical process to guarantee Venice and the lagoon an effective sea defence system.

To this end, in 1975 the State Ministry of Public Works issued a competitive tender, but the process ended without a project being chosen from those presented as no hypothesis for action satisfied all the mandated requirements. The Ministry subsequently acquired documents presented during the call for tender and passed them to a group of experts commissioned to draw up a project to preserve the hydraulic balance of the lagoon and protect Venice from floods (the "Progettone" of 1981).

A few years later, a further Special Law (Law no. 798/1984) emphasised the need for a unified approach to safeguarding measures, set up a committee for policy, coordination and control of these activities (the "Comitatone", chaired by the President of the Council of Ministers and consisting of representatives of the competent national and local authorities and institutions) and entrusted design and implementation to a single body, the Consorzio Venezia Nuova, recognising its ability to manage the safeguarding activities as a whole. The Venice Water Authority – Consorzio Venezia Nuova presented a complex system of interventions to safeguard Venice (the REA "Riequilibrio E Ambiente", "Rebalancing and the Environment" Project), which included mobile barriers at the inlets to regulate tides in the lagoon. In this context, between 1988 and 1992, experiments were carried out on a prototype gate (MOdulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, hence the name MOSE) and in 1989, a conceptual design for the mobile barriers was drawn up. This was completed in 1992 and subsequently approved by the Higher Council of Public Works then subjected to an Environmental Impact Assessment procedure and further developed as requested by the Comitatone. In 2002 the final design was presented and on 3 April 2003, the Comitatone gave the go-ahead for its implementation. The same year, construction sites opened at the three lagoon inlets of Lido, Malamocco and Chioggia.

5. Operating Principles

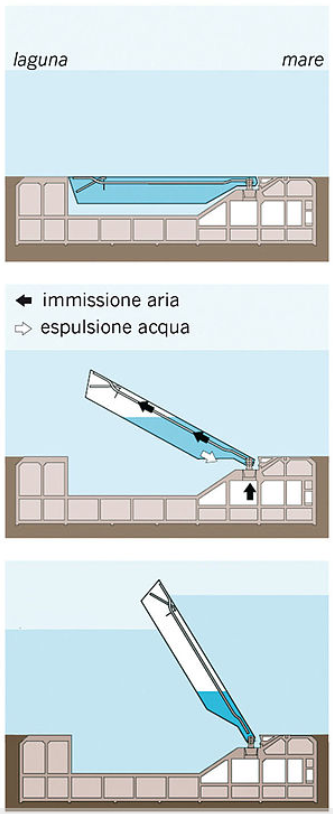

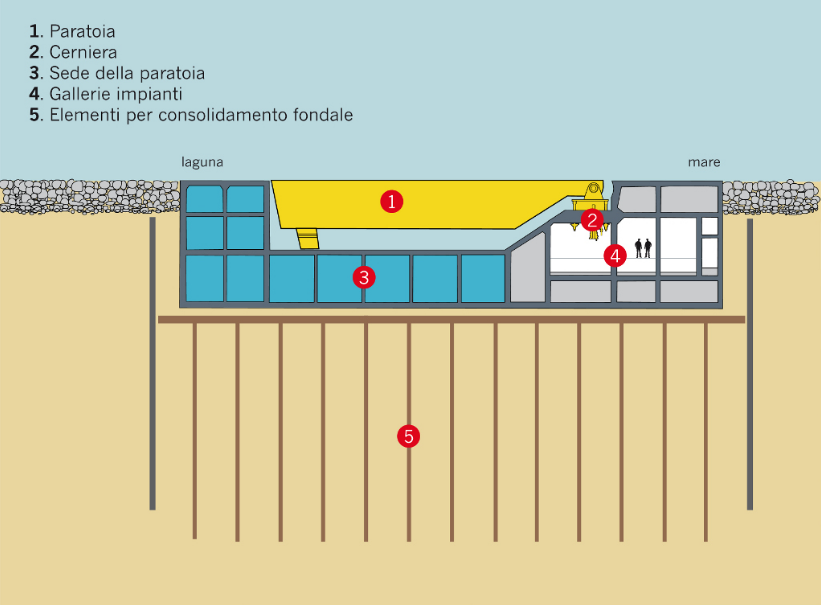

MOSE consists of rows of mobile gates at the three inlets, which temporarily separate the lagoon from the sea in the event of a high tide. There will be 78 gates divided into four barriers. At the Lido inlet, the widest, there will be two rows of gates of 21 and 20 elements respectively linked by an artificial island (the island connecting the two rows of gates at the centre of the Lido inlet will also accommodate the technical buildings housing the system operating plant); one row of 19 gates at the Malamocco inlet and one row of 18 gates at the Chioggia inlet. The gates consist of metal box-type structures 20 metres (66 ft) wide for all rows, with a length varying between 18.5 and 29 metres (61 and 95 ft) and from 3.6 to 5 metres (12 to 16 ft) thick, connected to the concrete housing structures with hinges, the technological heart of the system, which constrain the gates to the housing structures and allow them to move.

Under normal tidal conditions, the gates are full of water and rest in their housing structures. When a high tide is forecast, compressed air is introduced into the gates to empty them of water, causing them to rotate around the axis of the hinges and rise up until they emerge above the water to stop the tide from entering the lagoon. When the tide drops, the gates are filled with water again and return to their housing.

The inlets are closed for an average of between four and five hours, including the time taken for the gates to be raised (about 30 minutes) and lowered (about 15 minutes).

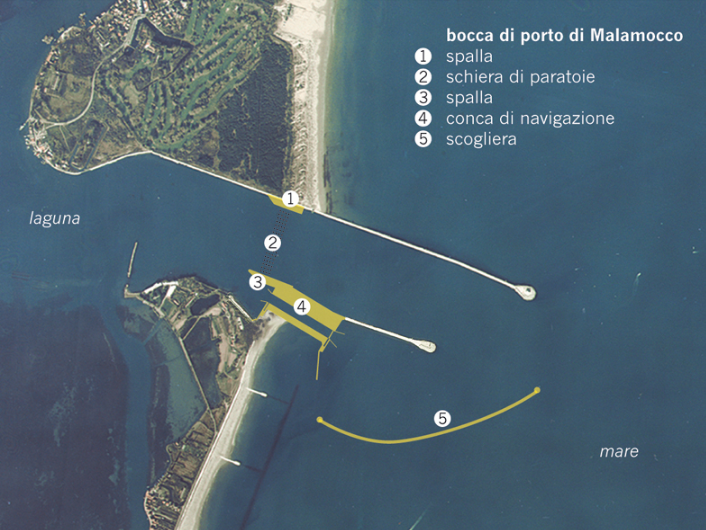

To guarantee navigation and avoid interruption of activities in the Port of Venice, when the mobile barriers are in operation, a main lock is under construction at the Malamocco inlet to allow the transit of large ships, while at the Lido and Chioggia inlets there will be smaller locks to allow emergency vessels, fishing boats and pleasure craft to shelter and transit.

Operating procedure dictates that the gates will be raised for tides of more than 110 centimetres (43 in) high. The authorities have established this as the optimum height with respect to current sea levels, but the gates can be operated for any level of tide. The MOSE system is also flexible and depending on the winds, atmospheric pressure and level of tide, it can oppose the high water in different ways – with simultaneous closure of all three inlets in the case of exceptional tides, by closing just one inlet at a time, or by partially closing each inlet—given that the gates are independent—for medium-high tides.

6. Construction

Construction of MOSE was authorised by the "Comitatone" on 3 April 2003 and the associated construction sites opened the same year. Work began simultaneously and continues in parallel at the three inlets of Lido, Malamocco and Chioggia. Work on the structural parts (foundations, mobile barrier abutments, gate housing structures), associated structures (breakwaters, small craft harbours, locks) and parts for operating the system (technical buildings, plant) is now at an advanced stage. Currently about 4000 people are employed in the construction of MOSE. As well as the construction sites at the inlets, fabrication of the main components of MOSE (the hinges, the technological heart of the system which constrain the gates to their housing and allow them to move, and the gates) is also proceeding. Restructuring of the buildings and spaces in the area of the Venice Arsenal where maintenance of MOSE and management of the system will be located is also underway.

6.1. Lagoon Inlet Construction Sites

Construction of MOSE at the inlets necessitates complex logistical organisation. These are located in a highly delicate environmental context so as to avoid interfering with the surrounding area as far as possible. The sites have been set up on temporary areas of water in order to limit occupation of the land adjacent to the inlets and reduce as far as possible the effect on activities taking place there. Materials (for example, site supplies) and machines are also moved via sea to avoid overloading the road system along the coast. Since the sites opened, all work has been carried out without interrupting transit through the inlet channels.

Below is a description of the work underway and already completed at each inlet, listed in order from North to South.

6.2. Lido Inlet

There will be two rows of gates at the Lido inlet (21 mobile gates for the North barrier Lido-Treporti and 20 mobile gates for the South barrier Lido-San Nicolò).

To the north of the inlet (Treporti), a small craft harbour consisting of two basins communicating through a lock, will allow small craft and emergency vessels to shelter and transit when the gates are raised. The sea-side basin was temporarily drained and sealed for use as the site to construct the gate housing structures for this barrier. Once the housing structures had been completed, the area was flooded with water to allow the housing structures to be floated out.

The housing structures for the gates in the north barrier (seven housing structures and two for the abutment connections) were positioned on the seabed. Four of this barrier's gates were installed and manoeuvred for the first time in October 2013; at the end of 2014, the installation of 21 gates was completed and operational for functional testing purposes (the so-called "blank tests").

At the south of the inlet (San Nicolò), the launch and the positioning of seven housing structures and two for the abutment connections has been completed (the structures have been fabricated on a temporary raised area in the Malamocco inlet and will be taken out to sea by a giant mobile platform which functions as a giant elevator).

At the centre of the inlet, a new island has been constructed to act as an intermediate structure between the two rows of mobile gates. This island will accommodate the buildings and plant for operating the gates (construction underway).

Outside the inlet, a 1,000-metre (3,300 ft) long curved breakwater is almost complete.

6.3. Malamocco Inlet

A temporary construction site has been set up alongside the basin to fabricate the gate housing structures to be positioned on the sea bed (Malamocco and Lido San Nicolò barriers, seven housing structures and two for the abutment connections for each barrier have been built).

In April 2014, the lock for the transit of large ships becomes operative to avoid interference with port activities when the gates are in operation.

Positioning of the gate housing structures for the Malamocco barrier was completed in October 2014.

The seabed in the area where the 19 gates will be installed has been reinforced.

Outside the inlet, a 1,300-metre (4,300 ft) long curved breakwater designed to attenuate tidal currents and define a basin of calm water to protect the lock has been completed.

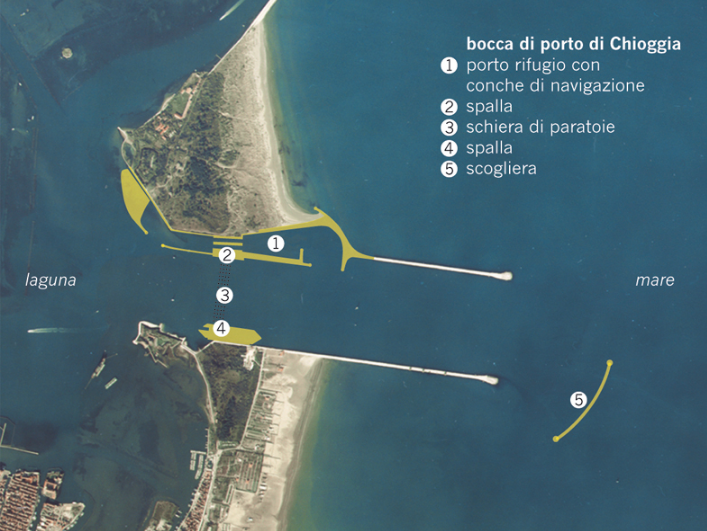

6.4. Chioggia Inlet

Work has been completed to construct a small craft harbour with double lock to guarantee transit of a large number of fishing vessels when the gates are in operation.

The sea-side basin has been temporarily drained and sealed for use as a construction site to fabricate the gate housing structures, as for the Lido north inlet barrier.

Positioning for the gate housing structures was completed in October 2014.

In the inlet channel, the seabed in the area where the 18 gates will be installed has been reinforced.

Outside the inlet, a 500 metres (1,600 ft) long curved breakwater has been completed.

6.5. Hinges

The hinges form the technological heart of the sea defence system. They constrain the gates to the housing structures, allow them to move and connect the gates to the operating plant. The steel gates consist of a male element (3 metres (9.8 ft) high and weighing 10 tonnes (9.8 long tons; 11 short tons)) connected to the gate, a female element (1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) high and weighing 25 tonnes (25 long tons; 28 short tons)) fastened to the housing structure and an attachment assembly to connect the male and female elements. A total of 156 hinges (two for each gate) will be fabricated, together with a number of reserve elements. Fabrication is currently underway.

6.6. Work Progress

On 10 July 2020, the first full test of the system was successfully conducted. Amid fanfare, the Italian prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, activated the 78 mobile barriers. MOSE is expected to be fully functional by the end of 2021.[6]

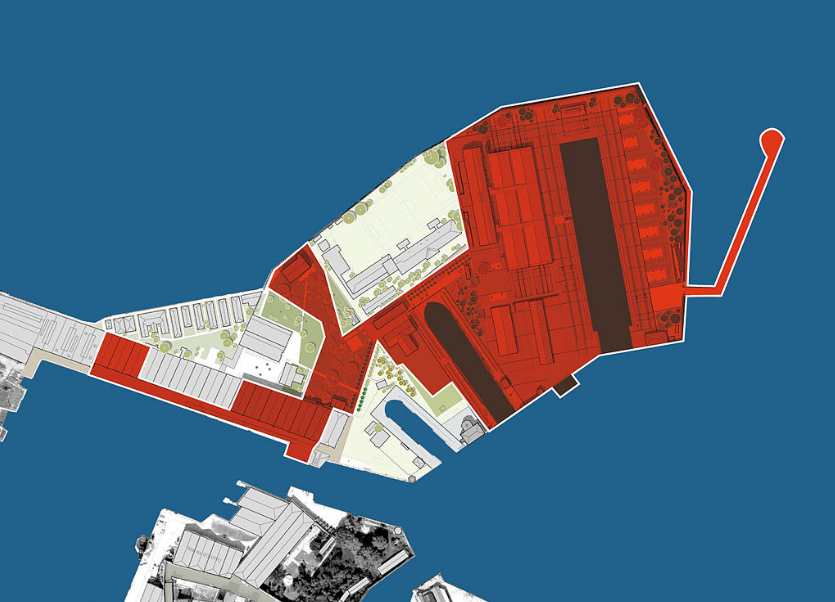

7. Mose in the Venice Arsenal

Since 2011, the Mose control centre and management functions for the lagoon system have been located in the Venice Arsenal, symbol of the former trading and military might of the historic Serenissima or "Serene Republic". Numerous historical buildings, in a state of decay and abandonment for decades, have already been restored and reorganisation of the area is underway to accommodate these new activities. Restoration has enabled a heritage of extraordinary historical and architectural value to be safeguarded and allowed buildings to be recovered and re-utilised. As home to MOSE management and control the arsenal will receive a new lease of life after years of abandonment, allowing its renaissance as a place of innovation and production, with important economic repercussions for the city and local area.

The historic arsenal buildings before and after restoration and construction of infrastructure to accommodate the new functions are shown below.

-

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748840

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748840 -

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748841

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748841 -

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748843

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748843 -

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748844

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748844

-

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748851

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748851 -

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748845

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748845 -

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748850

By Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24748850

In the control centre, key decisions will be taken on raising and lowering the mobile barriers according to measurements made by tide gauges positioned in front of the lagoon inlets to record the rising tide in real time. The command to raise the gate will be given when water reaches the level established by the procedure to begin the manoeuvre and guarantee that the water level in the lagoon does not exceed the requisite safe level.

8. Specifications

- Four mobile barriers are under construction at the lagoon inlets (two at the Lido inlet, one at Malamocco and one at Chioggia)

- The project utilises 1.6 kilometres (0.99 mi) of mobile barriers

- There are 18 kilometres (11 mi) of linear worksites on land and at sea

- MOSE has a total of 78 gates

- The smallest gate is 18.5 by 20 by 3.6 metres (61 ft × 66 ft × 12 ft) (Lido–Treporti row)

- The largest gate is 29.5 by 20 by 4.5 metres (97 ft × 66 ft × 15 ft) (Malamocco row)

- One lock for large shipping at the Malamocco inlet enables port activities to continue when the gates are in operation

- Three small locks (two at Chioggia and one at Lido-Treporti) allow the transit of fishing boats and other smaller vessels when the gates are in operation

- There are 156 hinges, two for each gate and a number of reserve elements

- Each hinge weighs 42 tons

- The gates can withstand a 3-metre (9.8 ft) maximum tide (to date, the highest tide has been 1.94 metres (6 ft 4 in))

- Mose has been designed to cope with a 60 centimetres (24 in) rise in sea level

- 30 minutes are required to raise the gates

- 15 minutes are required to lower the gates back into their housing structures

- During a tidal event, the inlet will remain closed for 4/5 hours, including barrier raising and lowering times

- The site currently employs 4,000 people directly or indirectly

9. Projections

The MOSE project is estimated to cost €5.496 billion, up €1.3 billion from initial cost projections.[7] On January 30, 2019 the last of the 78 gates was put in place.[8] In November 2019 the project was 94% completed and was expected to be ready by the end of 2021.[9]

10. Criticism, Corruption, and Court Cases

The project has met resistance from environmental and conservation groups such as Italia Nostra, and the World Wide Fund for Nature, who have made negative comments about the project.[10]

Criticisms of the MOSE project, which environmentalists and certain political forces have opposed since its inception, relate to the costs to the Italian State of construction, management, and maintenance, which are said to be much higher than those for alternative systems employed by the Netherlands and England to resolve similar problems. In addition, according to the project's opponents, the monolithic integrated system is not "gradual, experimental and reversible" as required by the Special Law for the Safeguarding of Venice. There have also been criticisms of the environmental impact of the barriers, not just at the inlets where complex leveling will be carried out (the seabed must be flat at the barrier installation sites) and the lagoon bed reinforced to accommodate the gates (which will rest on thousands of concrete piles driven deep underground), but also on the hydrogeological balance and delicate ecosystem of the lagoon. The NO MOSE front also emphasises what could be a number of critical points in the structure of the system and its inability to cope with predicted rises in sea level.

Over the years, nine appeals have been presented, eight of which have been rejected by the TAR (Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale, regional administrative court) and the Council of State. The ninth, currently under evaluation by the Administrative Tribunal, was presented by the Venice Local Authority and contests the favourable opinion of the Safeguard Venice Commission on the commencement of work at the Pellestrina site in the Malamocco inlet. Here, part of the MOSE gate housing caissons will be made using processes which, according to the local authority, could damage a site of special natural interest.

Environmental associations have also requested the intervention of the European Union, as project activities affect sites protected by the Nature 2000 Network and the European Directive on birds. Following a report of 5 March 2004 by the Venetian MP Luana Zanella, on 19 December 2005 the European Commission opened an infraction procedure against Italy for "pollution of the habitat" of the lagoon. The European Environmental Commission Directorate General considers that as it has "neither identified nor adopted—in relation to the impacts on the area 'IBA 064-Venice Lagoon' resulting from construction of the MOSE project—appropriate measures to prevent pollution and deterioration of the habitat, together with harmful disturbance of birds with significant consequences in the light of the objectives of article 4 of EEC Directive 79/409, the Italian Republic has not fulfilled its obligations under Article 4, Paragraph 4, of EEC Directive 79/409 of the Council of 2 April 1979 on the conservation of wild birds." Although the European Environmental Commission has said that the initiative is not intended to stop MOSE going ahead, the body has called on the Italian Government to produce new information on the impact of the sites and the environmental mitigation structures. The Water Authority and Consorzio Venezia Nuova both confirm that the construction sites are temporary and will be completely restored at the end of the work.

In 2014, 35 people, including Giorgio Orsoni, the Mayor of Venice, were arrested in Italy on corruption charges in connection with the MOSE Project. Orsoni was accused of receiving illicit funds from the Consorzio Venezia Nuova, the consortium behind the construction of the project, which he then used in his campaign to be elected mayor.[11] There were allegations that 20 million euros in public funds had been sent to foreign bank accounts and used to finance political parties.[12]

Following the legal proceedings occurred between 2013 and 2014, that involved part of the management bodies of the Consorzio Venezia Nuova and its Companies, the State intervened in order to ensure the conclusion of the flood defense system: in December 2014, the ANAC (National Anti-Corruption Authority) proposed the extraordinary management of the Consorzio, which followed the appointment of three Special Chief Executive Officers. The Special Administration of the Consorzio pursued its task to guarantee the proper completion of Mose and to ensure the conclusion of the defense system on 2018.

While MOSE's supporters say it can handle the threat of rising waters from global warming, others have doubted the project can face this challenge. Luigi D’Alpaos, a professor emeritus of hydraulics,[13] wrote that "MOSE is obsolete and philosophically wrong, conceptually wrong," for example.[1] The problem is that while the gates could hypothetically deal with rising waters, they could only do so by raising the floodgates so often that they would function as a "near-permanent wall." This, in turn, would devastate the lagoon's drainage and interchange with the Adriatic Sea; Venice's lagoon would become a "stagnant pool for algae and waste" if the gates were usually left up.[1]

11. Alternative Proposals

Over the years, various proposals were presented as an alternative to MOSE. Some offered widely different technological solutions while others suggested technologies to improve the efficiency of the system of mobile gates. At the request of the Mayor of Venice, Massimo Cacciari, approximately ten of these projects were examined in 2006 by round tables of experts appointed by individual responsible bodies, including the Higher Council of Public Works. In November 2006, negative assessments of the alternative proposals by these round tables led the government to give definitive approval for the MOSE project with the alternative proposals deemed ineffective or inappropriate to guarantee the defence of Venice.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Earth:MOSE_Project

References

- How Venice’s plan to protect itself from flooding became a disaster in itself 19 November 2019, www.washingtonpost.com, accessed 26 November 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/how-venices-plan-to-protect-itself-from-flooding-became-a-disaster-in-itself/2019/11/19/7e1fe494-09a8-11ea-8054-289aef6e38a3_story.html

- "Venice mayor blames record flood on climate change" (in en-GB). 2019-11-13. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50401308.

- Home › Centro Previsioni e Segnalazioni Maree › Dati e statistiche › Grafici e statistiche (includes 'ALTE MAREE >=+110 CM DAL 1872 AL 2018') www.comune.venezia.it, accessed 14 November 2019 https://www.comune.venezia.it/it/content/grafici-e-statistiche

- "Venice submerged by highest tides in half a century". Washington Post. 13 November 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/venice-partly-submerged-by-highest-tides-in-half-a-century/2019/11/13/fa36566e-05fa-11ea-8292-c46ee8cb3dce_story.html. "The [increased flooding] is a trend that jibes with the extremization of climate,” said Paolo Canestrelli, founder and former head of the municipality’s Tide Monitoring and Forecast Centre. “If we look at the course of history, we have documents dating back to 1872, and we can see that these phenomena didn’t used to exist."

- Law no. 171/1973, indicating the objectives and criteria for the measures to be implemented in the lagoon and defining the institutional parties involved and their relative responsibilities: the State for physical safeguarding and environmental restoration of the lagoon basin; the Veneto Region for water pollution abatement and the local Authorities of Venice and Chioggia for economic and social development, restoration and conservative improvement of urban structures

- Giuffrida, Angela (10 July 2020). "Venice's much-delayed flood defence system fully tested for first time". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/10/venice-much-delayed-flood-defence-system-fully-tested-first-time-italy.

- Portanova, Maria (2015-06-06). "Mose, in dieci anni 1,3 miliardi di costi in più. E allarmi inascoltati" (in Italian). http://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2014/06/06/mose-in-dieci-anni-13miliardi-di-costi-in-piu-e-allarmi-inascoltati/1015136/. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- Alberto Zorzi (2019-01-30). "Venezia. Mose, è stata posata l'ultima paratoia. In primavera via ai test". Corriere del Veneto. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190203211451/https://corrieredelveneto.corriere.it/venezia-mestre/cronaca/19_gennaio_30/venezia-02-03-fas1acorriereveneto-web-veneto-641be9d0-246b-11e9-b404-4020a844d8e7.shtml. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "A che punto è il MOSE a Venezia?". 2019-11-13. Archived from the original on 2019-11-13. https://web.archive.org/web/20191113210149/https://www.ilpost.it/2019/11/13/mose-venezia-lavori-conclusione/. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- Piazzano, Piero (September 2000). "Venice: Duels over Troubled Waters". UNESCO Courier. https://www.questia.com/library/1G1-66123018/venice-duels-over-troubled-waters. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Squires, Nick (4 June 2014). "Mayor of Venice arrested on lagoon barrier project corruption charges". The Daily Telegraph (London). https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/italy/10875534/Mayor-of-Venice-arrested-on-lagoon-barrier-project-corruption-charges.html. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Venice Mayor Orsoni held in Italy corruption inquiry, BBC News. 4 June 2014. Last updated at 10:02 GMT. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-27692334

- www.istitutoveneto.it: CV http://www.istitutoveneto.it/flex/FixedPages/Common/accademici.php/L/IT/IDS/346