Diabetic cardiomyopathy involves remodeling of the heart in response to diabetes that includes microvascular damage, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and cardiac fibrosis. Cardiac fibrosis is a major contributor to diastolic dysfunction that can ultimately result in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Under high glucose conditions cardiac fibroblasts, the final effector cell in the process of cardiac fibrosis, respond by making increased amounts of extracellular matrix. This process involves multiple molecular pathways.

- Heart

- Fibrosis

- Diabetes

- Myofibroblast

Extracellular Matrix Production

The ECM components primarily responsible for functional changes in the heart are the fibrillar collagens, specifically collagen I and III. HG conditions induce excess collagen synthesis by isolated neonatal and adult rat, neonatal and adult mouse, and human cardiac fibroblasts, which is not due to the effect of HG to increase osmolarity[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]. This increased collagen production is also true of cardiac fibroblasts isolated from an in vivo diabetic state and then cultured. For example, when compared to fibroblasts from non-diabetic individuals, collagen I production was increased from isolated right-atrial cardiac fibroblasts obtained from diabetic individuals without left-ventricular dysfunction, undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery[10]. Similarly, cardiac fibroblasts isolated from diabetic rodent models produce excess ECM when cultured. For example, cardiac fibroblasts isolated from Zucker obese diabetic rats showed increased collagen I messenger RNA (mRNA), although not collagen III mRNA, as well as increased total collagen protein synthesis[11]. Cardiac fibroblasts isolated from Leprdb/db diabetic mice also showed increased collagen I mRNA and protein in culture[12]. Thus, the cardiac fibroblast response to “diabetic” conditions is to produce excess ECM, which aligns with the fibrosis observed in the diabetic heart in experimental models including the Leprdb/db mouse[12]. Underscoring the clinical significance of this relationship, diabetes was associated with cardiac fibrosis in humans[13][14].

Conversion to a Myofibroblast Phenotype

Fibroblasts that produce more ECM often do so because of conversion to the more active myofibroblast phenotype; therefore, one would assume this to be the case for “diabetic” fibroblasts. Traditionally, myofibroblast conversion is assessed by an increase in α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) within the cell, making these cells contractile in nature and having the effect of contributing to the rearrangement and remodeling of the ECM[15]. Does HG cause a shift to the myofibroblast phenotype? The answer is not clear. Somewhat surprisingly, no differences were found, albeit at the mRNA level for α-SMA from isolated right-atrial cardiac fibroblasts obtained from diabetic and non-diabetic individuals without left-ventricular dysfunction, undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery[10]. Furthermore, Shamhart et al.[16] actually reported that less α-SMA was present in cultures of cardiac fibroblasts isolated from STZ type 1 diabetic rats, indicative of a reduction in myofibroblasts. This was supported by the finding of less α-SMA in the whole hearts of these STZ rats. On the other hand, cardiac fibroblasts isolated from Zucker obese diabetic rats induced slightly greater contraction of collagen gels than the lean counterpart, indicative of a more contractile myofibroblast phenotype[11]. This was supported by the finding of increased α-SMA mRNA in these Zucker cardiac fibroblasts. Similarly, isolated cardiac fibroblasts from normal neonatal rats showed increased α-SMA levels[17] and also generated greater gel contraction in response to HG conditions (25 mM)[7]. The increased contractile phenotype included increased active β1 integrin and increased α1 integrin[7]. Neonatal murine cardiac fibroblasts also demonstrate myofibroblast pheno-conversion in response to HG[9][18], and isolated adult rat cardiac fibroblasts underwent myofibroblast conversion (α-SMA) at a greater rate under HG conditions (25 mM) than normal glucose[6]. In this study, continual passaging led to even greater myofibroblast conversion. With such conflicting reports, it is unclear whether a HG environment promotes myofibroblast pheno-conversion. More important may be other culture conditions, including the length of time in culture, the substrate on which the cells are cultured, and number of passages. Comparing cells from different studies and different passage number may be akin to comparing apples and oranges when it comes to myofibroblast conversion. More in vivo identification of myofibroblasts may provide better information. What is clear, however, is that cardiac fibroblasts do not need to convert to the myofibroblast phenotype in order to produce excess ECM in response to HG.

Proliferation and Migration

Proliferation and increased migratory responses are also hallmark characteristics of more active fibroblasts. HG culture conditions induce rat and mouse cardiac fibroblast proliferation not due to increased osmolarity caused by excess glucose[6][9][18][19][20]. Cardiac fibroblasts isolated from the STZ rat model of type 1 diabetes were also shown to be more proliferative in culture than cells isolated from non-diabetic control mice[16], demonstrating similarities in fibroblast phenotype between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. These diabetic fibroblasts had reduced levels of the cell-cycle mediator p53. Since p53 is a tumor suppressor that utilizes p21 to inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase/cyclin activation and prevent cell-cycle progression, these data are supportive of cell-cycle progression and, hence, increased proliferation. Similarly, cardiac fibroblasts isolated from Zucker obese diabetic rats showed an increased proliferative rate compared to the lean controls when grown on a collagen I matrix[11]. However, reduced proliferation in response to HG (25 mM) was reported when naïve cardiac fibroblasts were grown on collagen[7]. This may indicate that the length of time of HG exposure is important, with cells from an in vivo diabetic state having prolonged exposure to HG versus cells from a normal in vivo state that are then treated with HG in vitro. In terms of human cardiac fibroblasts, there is some disagreement in the literature over proliferation responses, with one study finding increased proliferation for human cardiac fibroblasts obtained from biopsy of the right atrium of patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery or valve replacement (HG = 15 and 25 mmol/L)[21], and another study reporting no increase in proliferation for isolated right-atrial cardiac fibroblasts obtained from diabetic and non-diabetic individuals without left-ventricular dysfunction, undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery[10]. Some possible reasons for the differences in findings between these two studies include the following: (1) differences in gender composition of the individuals from which the fibroblasts were derived (four females and three males in Reference[21] versus one female and 11 males in Reference[10]); (2) the atrial fibroblasts were from non-diabetic individuals in Reference[21] and subsequently treated with HG media, whereas the atrial fibroblasts were derived from diabetic individuals and cultured in normal media in Reference[10]; (3) proliferation was assessed at one day in Reference[21], whereas the first time-point assessed in Reference[10] was at two days (final time-point = seven days). Thus, it is possible that there may be an acute proliferative response (one day) that then returns to normal by two days onward.

In terms of migration, under normal conditions, cardiac fibroblasts show a greater migratory tendency when cultured on collagen I and III over direct culture on plastic[6]. Addition of HG increases migration by roughly 10% on collagen I and III, as well as plastic. However, cardiac fibroblasts isolated from Zucker obese diabetic rats did not show increased migration in response to the scratch test[11]. An ECM substrate may be required to facilitate increased migration in response to HG.

Overall, there is clear conversion of cardiac fibroblasts to a phenotype that secretes excess amounts of collagen in response to a HG environment. This occurs whether cells are isolated from normal mice and then exposed to HG conditions, or whether cells are isolated from a diabetic environment, being either rodent models of type 1 or type 2 diabetes, or from diabetic humans. What is less clear is whether this phenotype change involves proliferation, myofibroblast conversion, and increased migratory responses. Primary cardiac fibroblasts change phenotype when cultured on plastic and with each subsequent passaging[6][22]. Thus, in vitro studies may report discrepant findings for proliferation, migration, and myofibroblast conversion due to differences in culture time and/or passage number. To our knowledge there are no studies that assessed the effects of HG on cardiac fibroblasts phenotype that cultured these cells on substrates that more closely mimic in vivo matrix stiffness characteristics. However, Fowlkes et al.[11] did culture cardiac fibroblasts isolated from diabetic male Zucker rats on collagen I matrix and compared the response to cells from lean controls. They demonstrated increased remodeling of collagen gels by diabetic fibroblasts, and that, while non-diabetic and diabetic fibroblasts showed an increase in proliferation on collagen I substrate compared to non-coated plates, there was no significant difference between the diabetic and non-diabetic cell types. Migration was not altered by culturing on collagen I for either diabetic or non-diabetic fibroblasts. It is also unclear whether the “diabetic” cardiac fibroblast phenotype is limited to one specific phenotype present at all stages of remodeling in the diabetic heart, or whether cardiac fibroblasts display a range of phenotypes depending on the stage of disease. Cardiac fibroblast phenotype is determined by numerous stimuli including mechanical force, growth factors, cytokines, and even the ECM[15]. These stimuli differ depending on the stage of remodeling and duration of the disease state and, thus, cardiac fibroblast phenotype may change depending on the stage of remodeling. This was recently demonstrated in myocardial ischemia where cardiac fibroblasts proliferate in the infarct/border zone region on days two to three, while converting to a myofibroblast phenotype on days three through 10[23]. Thus, the myofibroblast phenotype persists for many days after cessation of proliferation, indicating the changing fibroblast phenotype as the remodeling process progresses. Additionally, mRNA expression profiles differed by time-point, furthering the concept of temporally regulated fibroblast phenotype. In vitro studies demonstrated that stiffness of the substrate on which isolated cardiac fibroblasts are cultured can also alter cell phenotype, with greater incorporation of α-SMA with increased substrate stiffness[24]. Interestingly, mechanical stretch, even when cardiac fibroblasts were cultured on substrates mimicking in vivo stiffness, induced upregulation of multiple genes for ECM proteins including collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin[24]. While these examples are from ischemia and in vitro studies, it seems likely that mechanical and temporal changes in fibroblast phenotype in diabetes occur. This may account for the unclear findings regarding myofibroblast conversion and proliferation. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that investigated the cardiac fibroblast response to HG using substrates that more closely mimic the in vivo environment. Regardless, however, the main effect of HG is the excess production of ECM by cardiac fibroblasts that defines fibrosis.

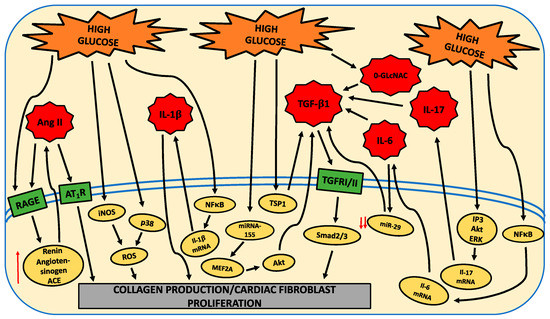

Pathways Mediating Fibroblast Phenoptye

There are numerous pathways modulated by HG that underlie the shift to a pro-fibrotic cardiac fibroblast phenotype. These are indicated in the following figure.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms21030970

References

- Juan Asbun; Ana Maria Manso; Francisco J. Villarreal; Profibrotic influence of high glucose concentration on cardiac fibroblast functions: effects of losartan and vitamin E. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2005, 288, H227-H234, 10.1152/ajpheart.00340.2004.

- Zhou, Y.; Poczatek, M.H.; Berecek, K.H.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E. Thrombospondin 1 mediates angiotensin II induction of TGF-beta activation by cardiac and renal cells under both high and low glucose conditions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 339, 633–641.

- Vivek P. Singh; Kenneth M. Baker; Rajesh Kumar; Activation of the intracellular renin-angiotensin system in cardiac fibroblasts by high glucose: role in extracellular matrix production. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2008, 294, H1675-H1684, 10.1152/ajpheart.91493.2007.

- M. Tang; M. Zhong; Y. Shang; H. Lin; J. Deng; H. Jiang; H. Lu; Y. Zhang; W. Zhang; Differential regulation of collagen types I and III expression in cardiac fibroblasts by AGEs through TRB3/MAPK signaling pathway. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2008, 65, 2924-2932, 10.1007/s00018-008-8255-3.

- Hugo Aguilar; Eduardo Fricovsky; Sang Ihm; Magdalena Schimke; Lisandro Maya-Ramos; Nakon Aroonsakool; Guillermo Ceballos; Wolfgang Dillmann; Francisco Villarreal; Israel Ramirez-Sanchez; et al. Role for high-glucose-induced protein O-GlcNAcylation in stimulating cardiac fibroblast collagen synthesis.. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2014, 306, C794-804, 10.1152/ajpcell.00251.2013.

- Patricia E. Shamhart; Daniel J. Luther; Ravi K. Adapala; Jennifer E. Bryant; Kyle A. Petersen; J. Gary Meszaros; Charles K. Thodeti; Hyperglycemia enhances function and differentiation of adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2014, 92, 598-604, 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0490.

- Xiaoyi Zhang; James A. Stewart; Ian D. Kane; Erin P. Massey; Dawn O. Cashatt; Wayne Carver; Effects of elevated glucose levels on interactions of cardiac fibroblasts with the extracellular matrix. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal 2007, 43, 297-305, 10.1007/s11626-007-9052-2.

- Kaliyamurthi Venkatachalam; Srinivas Mummidi; Dolores M. Cortez; Sumanth D. Prabhu; Anthony J. Valente; Bysani Chandrasekar; Resveratrol inhibits high glucose-induced PI3K/Akt/ERK-dependent interleukin-17 expression in primary mouse cardiac fibroblasts. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2008, 294, H2078-H2087, 10.1152/ajpheart.01363.2007.

- Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Dong, W.; Liang, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Inhibition of MEF2A prevents hyperglycemia-induced extracellular matrix accumulation by blocking Akt and TGF-beta1/Smad activation in cardiac fibroblasts. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 69, 52–61.

- Bryony Sedgwick; Kirsten Riches-Suman; Sumia A. Bageghni; David J. O’Regan; Karen E. Porter; Neil Turner; Investigating inherent functional differences between human cardiac fibroblasts cultured from nondiabetic and Type 2 diabetic donors. Cardiovascular Pathology 2014, 23, 204-210, 10.1016/j.carpath.2014.03.004.

- Vennece Fowlkes; Jessica Clark; Charity Fix; Brittany A. Law; Mary O. Morales; Xian Qiao; Kayla Ako-Asare; Jack G. Goldsmith; Wayne Carver; David B. Murray; et al. Type II diabetes promotes a myofibroblast phenotype in cardiac fibroblasts.. Life Sciences 2013, 92, 669-76, 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.01.003.

- Kirk R. Hutchinson; C. Kevin Lord; T. Aaron West; James A Stewart; Cardiac Fibroblast-Dependent Extracellular Matrix Accumulation Is Associated with Diastolic Stiffness in Type 2 Diabetes. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e72080, 10.1371/journal.pone.0072080.

- Clotilde Roy; Alisson Slimani; Christophe De Meester; Mihaela Silvia Amzulescu; Agnes Pasquet; David Vancraeynest; Christophe Beauloye; Jean-Louis Vanoverschelde; Bernhard Gerber; Anne-Catherine Pouleur; et al. Associations and prognostic significance of diffuse myocardial fibrosis by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2018, 20, 55, 10.1186/s12968-018-0477-4.

- Ahmed Al-Badri; Zeba Hashmath; Garrett H. Oldland; Rachana Miller; Khuzaima Javaid; Amer Ahmed Syed; Bilal Ansari; Swetha Gaddam; Walter R. Witschey; Scott R. Akers; et al. Poor Glycemic Control Is Associated With Increased Extracellular Volume Fraction in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2019–2025, 10.2337/dc18-0324.

- Kate M. Herum; Ida G. Lunde; Andrew D. McCulloch; Geir Christensen; The Soft- and Hard-Heartedness of Cardiac Fibroblasts: Mechanotransduction Signaling Pathways in Fibrosis of the Heart. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2017, 6, 53, 10.3390/jcm6050053.

- Patricia E. Shamhart; Daniel J. Luther; Ben R. Hodson; John C. Koshy; Vahagn Ohanyan; J. Gary Meszaros; Impact of type 1 diabetes on cardiac fibroblast activation: enhanced cell cycle progression and reduced myofibroblast content in diabetic myocardium. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009, 297, E1147-E1153, 10.1152/ajpendo.00327.2009.

- Hui Tao; Jun-Ye Tao; Zheng-Yu Song; Peng Shi; Qin Wang; Zi-Yu Deng; Xuansheng Ding; MeCP2 triggers diabetic cardiomyopathy and cardiac fibroblast proliferation by inhibiting RASSF1A.. Cellular Signalling 2019, 63, 109387, 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109387.

- Han Wu; Guan-Nan Li; Jun Xie; Ran Li; Qin-Hua Chen; Jian-Zhou Chen; Zhong-Hai Wei; Li-Na Kang; Biao Xu; Resveratrol ameliorates myocardial fibrosis by inhibiting ROS/ERK/TGF-β/periostin pathway in STZ-induced diabetic mice.. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2016, 16, 5, 10.1186/s12872-015-0169-z.

- P. Wang; H. W. Li; Y. P. Wang; H. Chen; P. Zhang; Effects of recombinant human relaxin upon proliferation of cardiac fibroblast and synthesis of collagen under high glucose condition. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2009, 32, 242-247, 10.1007/bf03346460.

- Liu, J.; Zhuo, X.; Liu, W.; Wan, Z.; Liang, X.; Gao, S.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, Y. Resveratrol inhibits high glucose induced collagen upregulation in cardiac fibroblasts through regulating TGF-beta1-Smad3 signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 227, 45–52.

- Susanne Neumann; Klaus Huse; Robert Semrau; Anno Diegeler; Rolf Gebhardt; Gayane Hrachia Buniatian; Gerhard H. Scholz; Aldosterone and D-glucose stimulate the proliferation of human cardiac myofibroblasts in vitro.. Hypertension 2002, 39, 756-760, 10.1161/hy0302.105295.

- Jon-Jon Santiago; Aran L. Dangerfield; Sunil G. Rattan; Krista L. Bathe; Ryan H. Cunnington; Joshua E. Raizman; Kristen M. Bedosky; Darren H. Freed; Elissavet Kardami; Ian Dixon; et al. Cardiac fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation in vivo and in vitro: Expression of focal adhesion components in neonatal and adult rat ventricular myofibroblasts. Developmental Dynamics 2010, 239, 1573-1584, 10.1002/dvdy.22280.

- Xing Fu; Hadi Khalil; Onur Kanisicak; Justin G. Boyer; Ronald J. Vagnozzi; Bryan D. Maliken; Michelle A. Sargent; Vikram Prasad; Iñigo Valiente-Alandi; Burns C. Blaxall; et al. Specialized fibroblast differentiated states underlie scar formation in the infarcted mouse heart.. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2018, 128, 2127-2143, 10.1172/JCI98215.

- Kate M. Herum; Jonas Choppe; Aditya Kumar; Adam J. Engler; Andrew D. McCulloch; Mechanical regulation of cardiac fibroblast profibrotic phenotypes. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2017, 28, 1871-1882, 10.1091/mbc.E17-01-0014.