Biblical Sabbath is a weekly day of rest or time of worship given in the Bible as the seventh day. It is observed differently in Judaism and Christianity and informs a similar occasion in several other faiths. Though many viewpoints and definitions have arisen over the millennia, most originate in the same textual tradition of "Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy". Observation and remembrance of Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments (the fourth in the original Jewish, the Eastern Orthodox, and most Protestant traditions, the third in Roman Catholic and Lutheran traditions), sometimes referred to individually as the Sabbath Commandment. Most people who observe Biblical Sabbath regard it as having been made for man (Mark. 2:27) at Creation (Ex. 20:8–11), and instituted as a perpetual covenant for the people of Israel (Ex. 31:13-17, Ex. 23:12, Deut. 5:13-14), a rule that also applies to proselytes, and a sign respecting two events: the seventh day, during which God rested after having completed Creation in six days (Gen. 2:2-3, Ex. 20:8-11), and God's deliverance of the Israelites from Egypt (Deut. 5:12-15).

- proselytes

- israelites

- deliverance

1. Etymology

1.1. Sabbath

The Anglicized term "Sabbath" is in Hebrew Shabbath[1] meaning "day of rest".

The name form is "Shabbethai"[2] a name appearing three times in the Tanakh. The Talmud also contains a pun on shebeth, where it secondarily means "dill", a spice. Another related word is modern Hebrew shevita, a labor strike, with the same focus on active cessation of labor. And in over thirty languages other than English, the common name for Saturday is a cognate of "Sabbath".

A cognate Babylonian Sapattum or Sabattum is reconstructed from the lost fifth Enûma Eliš creation account, which is read as: "[Sa]bbatu shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly". It is regarded as a form of Sumerian sa-bat ("mid-rest"), rendered in Akkadian as um nuh libbi ("day of mid-repose").[3]

The dependent Greek cognate is Sabbaton,[4] used in the New Testament 68 times. Two inflections, Hebrew Shabbathown[5] and Greek "σαββατισμός" (Sabbatismós,[6]), also appear. The Hebrew form refers to High Sabbaths. The Greek form is cognate to the Septuagint verb sabbatizo (e.g., Ex. 16:30; Lev. 23:32; 26:34; 2 Chr. 36:21). In English, the concept of "Sabbatical" is cognate to these two forms.

The King James Bible uses the English form "sabbath(s)" 172 times. In the Old Testament, "sabbath(s)" translates Shabbath all 107 times (including 35 plurals), plus shebeth three times, shabath once, and the related mishbath once (plural). In the New Testament, "sabbath" translates Sabbaton 59 times and prosabbaton once (the day before Sabbath); Sabbaton is also translated as "week" nine times, by synecdoche.

1.2. Shmita

Sabbath Year or Shmita (Hebrew: שמטה, Shemittah, Strong's 8059, literally "release"), also called Sabbatical Year, is the seventh (שביעי, shebiy'iy, 7637) year of the seven-year agricultural cycle mandated by Torah for the Land of Israel, relatively little observed in Biblical tradition, but still observed in contemporary Judaism. During Shmita, the land is left to lie fallow and all agricultural activity—including plowing, planting, pruning and harvesting—is forbidden by Torah and Jewish law.[7] By tradition, other cultivation techniques (such as watering, fertilizing, weeding, spraying, trimming and mowing) may be performed as preventative measures only, not to improve the growth of trees or plants; additionally, whatever fruits grow of their own accord during that year are deemed hefker (ownerless), not for the landowner but for the poor, the stranger, and the beasts of the field; these fruits may be picked by anyone. A variety of laws also apply to the sale, consumption and disposal of Shmita produce. When the year ended, all debts, except those of foreigners, were to be remitted (Deut. 15:1-11); in similar fashion, Torah requires a slave who had worked for six years to go free in the seventh year. Leviticus 25 promises bountiful harvests to those who observe Shmita, and describes its observance as a test of religious faith. The term Shmita is translated "release" five times in the Book of Deuteronomy (from the root שמט, shamat, "desist, remit", 8058).

2. Tanakh

2.2. Torah

- Book of Genesis: In 1:1-2:4, God creates the heavens and earth in six days (each day is defined as evening and morning) and rests on the seventh day, which he thus confers with special status.

This passage uses root form shabath, rather than intensified form Shabbath; neither the noun form nor a positive Sabbath command appears in Genesis. In 8:4, Noah's ark comes to "rest" in the seventh month (later revealed as the month of Shabbathown); here the word for "rest" is not shabath but its synonym nuwach, the root of Noah's name.So God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it God rested from all his work that he had done in Creation. —Gen. 2:3

- Book of Exodus: In 16:23-30, immediately after the Exodus from Egypt, Sabbath is revealed as the day upon which manna and manna gathering is to cease weekly; the first of many Sabbath commands is given, in both positive and negative forms.

In 20:8-11, one month later, it is enjoined to be remembered as a memorial of Creation, as one of the Ten Commandments, the covenant revealed after God liberated Israel from Egyptian bondage.Six days you shall gather it, but on the seventh day, which is a Sabbath, there will be none .... Remain each of you in his place; let no one go out of his place on the seventh day. —Ex. 16:26, 16:29

In 31:12-17, Sabbath is affirmed as a perpetual sign and covenant, and Sabbath-breakers are officially to be cut off from the assembly or potentially killed. Summarized again in 35:2-3, verse 3 also forbids lighting a fire on the Sabbath.Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the LORD your God. On it you shall not do any work .... For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy. —Ex. 20:8-11

- Book of Leviticus: In 16:31, Yom Kippur is stated to be "Sabbath of Sabbaths". In 19, many of the Ten Commandments are repeated, including Sabbath (19:3, 19:30). In 23, Moses defines weekly Sabbath, along with seven annual High Sabbaths, which do not necessarily occur on weekly Sabbath and are additional to the weekly "LORD's Sabbaths". One High Sabbath, Day of Atonement, is specifically defined as occurring from the evening of the prior day until the following evening. In 24:8, the showbread is to be laid out in the tabernacle every Sabbath. In 25:2-6, Shmita is given as a year of rest for land every seven years. In 26:2, 26:34-35, 26:43, Sabbath is again enjoined, and Moses warns of the curse that if Israel disobeys, it will go into exile while the land enjoys Sabbaths denied to it during the time of rebellion.

- Book of Numbers: In 15:32-36, a man gathering firewood on Sabbath is put to death; the potential punishment for desecrating Sabbath (stoning) is the most severe in Jewish law. In 28-29, the offerings for Sabbath, new moon, and High Sabbaths are enjoined.

- Book of Deuteronomy: In 5:12-15, the Ten Commandments are restated; instead of referring again to Creation, Sabbath is enjoined to be observed as a memorial or sign of The Exodus and Redemption of Israel from Egypt under God's protection.

2.2. Prophets

- 2 Kings: In 4:23, when Elisha's patroness goes away suddenly to seek him, her husband questions why, since it was neither new moon nor Sabbath. In 11:5-9, Joash becomes king, protected from usurper Athaliah by the additional troops present for changing of duty on Sabbath. In 16, the colonnade built for Sabbath use and its royal entranceway are removed from the temple by King Ahaz.

- Book of Isaiah: Isaiah mentions Sabbath repeatedly, including in its first and last chapters. In 1:13, he describes corrupted Sabbath tradition, called by God "your" assembly (as opposed to his own). In 56:1-8 and 58:13-14, Isaiah commends honoring the holiness of Sabbath, rather than using it to go one's own way or to do idly as one pleases. Because of this passage, it is customary, in Judaism, to avoid talk about money or business matters on Sabbath; and, among Latter-day Saints, to give full attention to spiritual matters, to perform only righteous activities, and to prepare only simple foods on Sabbath. In 66:22-23, he foresees what is understood as the Messianic Kingdom, in which new moons and Sabbaths are occasions for the righteous to worship in God's presence, and to meditate on the unquenched fire consuming the wicked.

- Book of Jeremiah: In 17:19-27, Jeremiah declaims against carrying burdens out of houses or out of the city gates on Sabbath, as was commonly done by merchants in his day. Jeremiah also prophesies that Israel will be a desolation for seventy years (25:11), interpreted later as land Sabbaths as also prophesied by Moses.

- Book of Ezekiel: In 20:12-26, Ezekiel records God's giving of laws, precepts, and Sabbaths, and Israel's rejecting them; Sabbaths are explicitly called a sign between God and Israel. In 22:8, 22:23-31, 23:38, he states that Israel has profaned and hidden its eyes from Sabbath. In 44:24, Ezekiel foresees a Messianic Temple, in which the priests keep Sabbath as truly holy. In 45:17, 46:1-12, he sees the east gate shut on the "six working days" and open on Sabbath and new moon, and a prince making burnt offerings on those festivals as well.

- Book of Hosea: In 2:11, casting Israel as an adulterous wife, God vows to end "her" festivals, new moons, and Sabbaths.

- Book of Amos: In 8:5, Amos objects to those who inquire when Sabbath or new moon will be over so that marketing can begin again, classifying this practice as comparable to that of dishonest weights.

2.3. Writings

- Book of Psalms: 92 is a song specifically for Sabbath.

- Book of Lamentations: In 1:7, Israel's enemies gloat over its "cessation" (mishbath), after the destruction of the first temple. In 2:6, this destruction and Israel's rejection is linked to Israel forgetting its appointed times and Sabbaths.

- Book of Nehemiah: In 9:14, the Levites, who have called a public fast, thank God for Sabbath, the mitzvoth (commandments), and the Torah. In 10:31-33, the people respond by swearing not to buy on Sabbath or holy day. In 13:15-22, Nehemiah observes many kinds of business transacted on Sabbath, rejects it as profanation, locks the city gates for the whole of Sabbath and has them guarded, and threatens force against merchants who spend the night outside. Sabbath begins after evening shadows fall on the gates.

- 1 Chronicles: In 9:32, the task of preparing Sabbath showbread is shown to have been assigned to kinsmen of Korah from the clan of Kohath. In 23:31, King David assigns Levites to stand and sing thanks and praise whenever the burnt offerings are given for Sabbath, new moon, and the other designated days.

- 2 Chronicles: In 2:4 (2:3, Hebrew) and 8:12-13, Solomon dedicates the first temple for daily, weekly, monthly, and annual offerings. In 23:4-8, Joash becomes king, protected from usurper Athaliah by the additional troops present for changing of duty on Sabbath. In 31:3, Hezekiah rededicates the same offerings as Solomon. In the last chapter of the Tanakh in Hebrew order (at 36:21), the prophecies of Moses and Jeremiah are combined as having been fulfilled in seventy years of captivity in Babylon, during which the land kept its Sabbaths.

3. New Testament

3.1. Gospels

Matthew, Mark, and Luke contain several synoptic accounts, which John occasionally concurs in.

- Exorcism in Capernaum (Mk. 1:21-39, Lk. 4:31-43): Jesus makes a practice of teaching in the Capernaum synagogue on Sabbath. One Sabbath he exorcises an unclean spirit, and also heals Peter's wife's mother. After sundown that day, he heals many people, and early in the morning of the first day, he goes out to pray alone.

- Lord of the Sabbath (Mt. 12:1-8, Mk. 2:23-28, Lk. 6:1-5): When his disciples pick heads of wheat and eat them, Jesus tells objectors that, because Sabbath was made for man, the Son of Man is Lord of Sabbath. Sabbatarians believe that Sabbath-keeping is central to following Christ, and that he highly regarded Sabbath; some non-Sabbatarian Protestants and Catholics believe that Christ has power to abrogate Sabbath via a "better dispensation", and that he did so as with all ceremonial law.[8] The doctrine that Christ "made" all Creation (Jn. 1:3-10, Col. 1:16) implies that "Sabbath was made", and observed, by Christ (Mk. 2:27), during Creation; this is taken as earning him the identification "Lord of Sabbath".

- Healing of the Withered Hand (Mt. 12:9-21, Mk. 3:1-6, Lk. 6:6-11): Knowing he is being watched, Jesus heals a man who had a withered hand, arguing that doing good and saving life is permitted and right on Sabbath. This passage follows his proclamation as Lord of Sabbath in Mark and Luke, but in Matthew follows his quotation of Jer. 6:16 that he would give rest for his disciples' souls; this is taken as indicating Matthew intended to teach that Sabbath's true or spiritual fulfillment is found in coming to Jesus.[9]

- Rejection of Jesus (Mk. 6:1-6, Lk. 4:16-30): As is his custom, Jesus attends the Nazareth synagogue on Sabbath and stands to read. He preaches against skeptical demands for miracles and states that he is rejected there in his hometown.

- Events unique to John: In 5:9-18, Jesus heals a paralytic at the Pool of Bethesda and tells him to carry his mat, spurring accusations of Sabbath-breaking. In 7:22-23, Jesus argues that healing in general is equivalent to permitted Sabbath activity of circumcision, regarded as a cleansing ritual. In 9, Jesus makes clay with spittle on Sabbath and heals a man born blind, and is investigated by Pharisees.

- Events unique to Luke: In 13:10-17, Jesus heals a woman who had been bent over double for 18 years, arguing that setting her free is equivalent to permitted Sabbath activity of loosing one's animals to water them. In 14:1-6, Jesus heals a man with dropsy (swollen with fluid), arguing that this is equivalent to permitted Sabbath activity of rescuing an animal from a well. In 18:9-14, Jesus' parable of the Pharisee and the Publican, the Pharisee fasts twice a week, literally twice per Sabbath (the word Sabbaton means "week" by synecdoche).

- Olivet Discourse, unique to Matthew: In 24, describing then-future apocalypses such as the Second Coming, Jesus requests prayer (at 24:20) that the coming time, when Judah must escape to the hills, not occur in winter or on Sabbath. Sabbatarians believe that Jesus based on this text expected Sabbath to be kept long after his death;[10] others believe Jesus foresaw a non-Sabbatarian future community hampered by surrounding Sabbatarianism.[11]

- Crucifixion of Jesus (Mt. 27, Mk. 15, Lk. 23, Jn. 19): Jesus is crucified on Preparation Day, the day before Sabbath; differing chronologies interpret this either as Friday (before weekly Sabbath) or Nisan 14 (before High Sabbath) or both. Joseph of Arimathaea buries him before this Sabbath begins. The women who wished to prepare his body keep Sabbath rest according to the commandment, intending to finish their work on the first day of the week (the day after weekly Sabbath); one reading of the text permits "they rested" to include a hint that the body of Jesus rests on Sabbath as well. Seventh-day Sabbatarians see no change in God's law, regarding it as in force and affirmed by the evangelists after Jesus died on the cross.[12] Others regard Sabbath as changed by the cross, either to Lord's Day or to spiritual Sabbath.

- Resurrection of Jesus (Mt. 28, Mk. 16, Lk. 24, Jn. 20): Jesus is raised from the dead by God and appears publicly on the first day of the week to several women. Jesus appears to Peter and again on the evening beginning the second day (i.e., after two disciples traveled seven miles from Emmaus, having begun when it was almost evening and getting dark, Lk. 24:28-36). The text stating that "Jesus rose early on the first day of the week" (Mk. 16:9) is often inferred as speaking indirectly of Sabbath change; this conclusion is not direct in any Scripture, and the verse is not found in the two most ancient manuscripts (the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus) and some other ancient manuscripts, though it appears in Irenaeus and Hippolytus in the second or third century.[13]

3.2. Epistles

- Book of Acts 1-18: In 1:12, the distance from the Mount of Olives to Jerusalem is called a "Sabbath journey", the distance Jewish law permitted one to walk on the Sabbath. In 2, the Spirit of God is given to the disciples of Christ on Pentecost, who baptize 3,000 people into the apostolic fellowship; though the weekday is not mentioned, this is usually calculated as falling on the day after Sabbath. In 13:13-45, 16:13, 17:2, and 18:4, as is his custom, Paul preaches on Sabbath to communal gatherings of Jewish and Gentile Christians, usually in synagogue, in Pisidian Antioch, Philippi, Thessalonica, and Corinth (the meeting of Philippians was a riverside women's prayer group, in Gentile territory). Seventh-day Sabbatarians believe that Luke's recording Paul's sitting down in the synagogue indicates they kept a rest day and affirmed the seventh day as Sabbath,[12] while others believe that Paul merely preached on days that the Jewish portion of his audience would be available. In 15:19-29, the Apostolic Decree, James proposes four limited rules for Gentile proselytes in response to the question of whether Gentiles should be directed to follow the Mosaic Law; the apostles then write that no greater burden is laid on the Gentiles. James also states that Moses is read every Sabbath, which can be construed either as discounting Moses as too unnecessary to promote (the Law being split into parts with Gentiles ordered to follow only Noachide Laws), or as supporting Moses as too ubiquitous to promote (the Law being a unity to grow into).

- Acts 20: When the Christians meet to break bread, during an all-night worship service in Troas, Paul preaches and raises Eutychus from the dead, the night after Sabbath (i.e., Saturday night and Sunday morning); the first day had begun at sundown (cf. Judg. 14:17-18). Though Paul's special farewell service, this event is otherwise considered a regular Christian Eucharistic observance.[14][15] Paul then immediately walks eighteen miles from Troas to Assos, boards a boat, and continues to Mitylene. Seventh-day Sabbatarians state that Paul (as a lifelong Sabbath keeper) would not have done so on Sunday, if he had regarded Sunday as Sabbath. Non-Sabbatarians state that Paul did not keep any day of the week as Sabbath (citing his later passages) and that the early church met on the first day of the week but without rigor. First-day Sabbatarians state that he did not extend the travel prohibition to the first day.

- Book of Romans: In 14:5-6, without mentioning Sabbath, Paul emphasizes being fully convinced of one's practice, whether esteeming one day above another, or esteeming every day alike. Each interpretative framework regards this passage as demonstrating that ritual observance of others' Sabbaths is not required, but is optional according to the conscience of each individual Christian.

- 1 Corinthians: In 11:1, Paul exhorts readers to follow his example in religious practice as he follows Christ's. In 16:1-2, Paul encourages the setting aside of money on the day after Sabbath for a collection for the Christians in Jerusalem; it is not stated whether this is in conjunction with a first-day group meeting. As in Acts 20, the word "week" translates Sabbaton in "the first day of the week".

- Galatians: In 4:10-11, spiritual enslavement to special days, months, seasons, and years is rejected. In context, Paul speaks of enslavement to "the elemental things of the world" and "those weak and miserable principles" (4:3, 4:9), and allegorizes the Israelites as "children who are to be slaves" (4:24). The theme of 5 is freedom. Seventh-day Sabbatarians believe Paul was promoting freedom in Sabbath observance and rejecting either observance of non-Levitical Gnostic practices, or else legalistic observance of Biblical festivals (cf. Col. 2:9-17);[16] others believe Paul spoke about Judaizers and was rejecting seventh-day Sabbath as not prescribed in the New Covenant, represented by Mount Zion above and by freedom.

- Colossians: In 2:9-17, the rule is laid down that no one should pass judgment on anyone else in regard to High Sabbaths, new moon, and Sabbath. Paul states that these yet remain as a shadow of Messianic events that are still coming as of his writing. The withholding of judgment has been interpreted variously as indicating either maintenance, transference, or abolition of Sabbath. First-day Sabbatarians and non-Sabbatarians often regard the Mosaic law as being the "record of debt" (ESV) nailed to the cross. Some seventh-day Sabbatarians regard only High Sabbaths as abolished due to their foreshadowing the cross, holding it impossible for weekly Sabbath (which preceded sin) to foreshadow deliverance from sin in the cross.[17] Others regard Sabbath, new moon, and High Sabbaths not as nailed to the cross but as foreshadowing the eternal plan of God.[18]

- Book of Hebrews: In 4:1-11, Sabbath texts are analyzed with the conclusion that some form of Sabbath-keeping (sabbatismos) remains for God's people; the term generically means any literal or spiritual Sabbath-keeping.

- Revelation: In 1:10, John the Beloved states that he was "in Spirit" in the "Lord's Day", a term apparently familiar to his readers, without mentioning Sabbath. First-day Sabbatarians hold that this means he was worshipping on Sunday, the day of Christ's resurrection (cf. Acts 20:7, 1 Cor. 16:2, later patristic writings). Seventh-day Sabbatarians hold that this means he was brought by the Spirit into a vision of the Day of the Lord (cf. Is. 58:13-14, etc.). Both lay claim to the name "Lord's Day" for Sabbath. In 20:1-10, the millennial reign of Christ is described, which is often interpreted as a seventh (Sabbatical) millennium.

4. Apocrypha

- 1 Esdras: 1:58 quotes 2 Chr. 36:21, relying on the prophecies of Jer. 25 and of Lev. 26. In 5:52, Joshua the High Priest and Zerubbabel lead the rededication of the altar for Sabbath, new moon, and (annual) holy feasts.

- 1 Maccabees: In 1:39-45, under Antiochus IV Epiphanes, Jerusalem's Sabbaths become a reproach and profanation. In 2:32-41, he wars against the Maccabees and followers on Sabbath, one thousand of whom are killed after refusing to come out; Mattathias and his friends decree they will battle on Sabbath in self-defense. In 9:34-49, Bacchides prepares to attack on Sabbath but is defeated by Jonathan Maccabeus. In 10:34, Demetrius I Soter declares that Jews will be free to celebrate feasts, Sabbaths, new moons, and solemn days, but is not received.

- 2 Maccabees: In 5:25-26, a Mysian captain named Apollonius attacks all those celebrating Sabbath. In 6:6-11, Antiochus criminalizes Sabbath and ancient fasts, and those keeping Sabbath secretly in caves are burned to death. In 8:26-28, after defeating Nicanor's army, the men of Judas Maccabeus leave off pursuit on Preparation Day, instead gathering spoil, occupying themselves about Sabbath, and praising and thanking God; after Sabbath they distribute the spoil to the maimed, widows, and orphans, and then themselves and their servants. In 12:38-39, Judas's men reach Adullam and purify themselves when the seventh day comes, according to custom, and keep Sabbath there, burying those dead in battle on the day after, according to custom (i.e., the first day). In 15:1-4, Nicanor resolves to attack Judas in Samaria on Sabbath but is entreated to forbear by the Jews accompanying him, who argue that the living Lord commanded the seventh day to be kept in holiness.

- Judith: In 8:6, Judith fasts and lives in a tent for three years and four months, except for Sabbath eve, Sabbath, new moon eve, new moon, and feasts and solemn days. In 10:2, it is repeated that she only dwelt in her house for Sabbath and feast days.

5. Religious Books from No Biblical Canon

- Infancy Gospel of Thomas 2.1-5: The five-year-old Jesus forms twelve sparrows out of clay on Sabbath, which then fly away, chirping; he also gathers together flowing water into pure pools by his word at the same time, and pronounces an efficaceous curse on the child who disperses the pools. Jews object to Joseph about these things.

- Gospel of Thomas 27: Jesus warns, "Fast as regards the world ... Observe the Sabbath as a Sabbath."

- Gospel of Peter 2.5, 7.27: Herod commends the swift burial of Jesus because it is the day before Sabbath and the Feast of Unleavened Bread. That day, after the ninth hour (3:00 p.m.), the disciples mourn and weep "night and day until the Sabbath" (sunset or 6:00 p.m.; the idiom "night and day" can import a portion of a day).

- Gospel of Nicodemus (Acts of Pilate) 1.1, 2.6, 4.2, 6.1, 12.1-2, 15.6, 16.1-2: Annas, Caiaphas, and others accuse Jesus of polluting Sabbath and wanting to destroy Torah, because he healed on Sabbath. Joseph of Arimathea is arrested and sealed up in a room on the day of Jesus' death, the day before Sabbath; he is ordered by a council to be dishonored on the day after Sabbath, but is not found when the door is opened. Joseph later testifies (on the day before another Sabbath) that he had remained locked up all Sabbath but, on midnight the day after, beheld a lightning flash and was led outside by the risen Jesus.

- Acts of Paul, in the latter half of the second century: Paul prays "on the Sabbath as the Lord's Day [kyriake] drew near."

- Damascus Document, known from the Dead Sea Scrolls monastic community, as well as a previously found copy, contains some of the most detailed Sabbath regulations anywhere: Sabbath is said to begin from when the setting sun "is above the horizon by its diameter"; any discussion of business or commerce on Sabbath is specifically forbidden, as is housecleaning, opening a container, or taking anything in or out of one's house; and the limit for walking outside one's city is set at 1000 cubits, or 2000 cubits if following a herd animal. One may bathe and drink water directly from the river on Sabbath, but not fill a container with water. Also, it is permitted to rescue a human being who falls into a well on the Sabbath, but significantly, not permitted to rescue an animal from a well on the Sabbath.

6. Frameworks

Three primary interpretative frameworks exist, with many subcategories. Interpretation is complicated by the differing meanings attributed to unambiguous seventh-day Sabbath prior to the resurrection of Jesus; the ambiguity of events after the resurrection, including first-day and seventh-day events (Acts 20:7, 1 Cor. 16:2, perhaps Rev. 1:10; Acts 1:12, 13:13-45, 15:19-29, 16:13, 17:2, and 18:4); and several early Christian observances being attested as daily or on nonspecific days (Mk. 2:1-2, Lk. 19:47-20:1, Acts 2:42-47). Early Christians also observed Jewish practices as a sect of Judaism (Acts 3:1, 5:27-42, 21:18-26, 24:5, 24:14, 28:22), and observed Tanakh feasts (Passover, Acts 12:3-4, 20:6, 1 Cor. 5:7-8, 15:20, Jude 12; Pentecost, Acts 2:1, 18:21, 20:16, 1 Cor. 16:8; Atonement, Acts 27:9). Interpreters of each framework consider the high regard for the New Covenant described in Jer. 31:31 (cf. Heb. 8:1-13) as supporting their Sabbath positions.

6.1. Seventh Day

At least two branches of Christianity keep a seventh-day Sabbath, though historically they are not derived one from the other: the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Seventh-day Sabbatarians. Of different outlooks in some respects, they share others. Just as in the Jewish calendar, the Orthodox begin and end every ecclesial day at sunset, including the Sabbath. Both branches thus observe the Sabbath from what the civil calendar identifies as Friday sunset until Saturday sunset. Both identify the Sabbath with the day of rest established by God as stated in Genesis 2, a day to be kept holy. Both identify Jesus Christ as the Lord of the Sabbath, and acknowledge that he faithfully kept the Sabbath throughout his life on earth. Both accept the admonitions of St. Ignatius on the keeping of the Sabbath.[19]

Seventh-day Sabbatarians

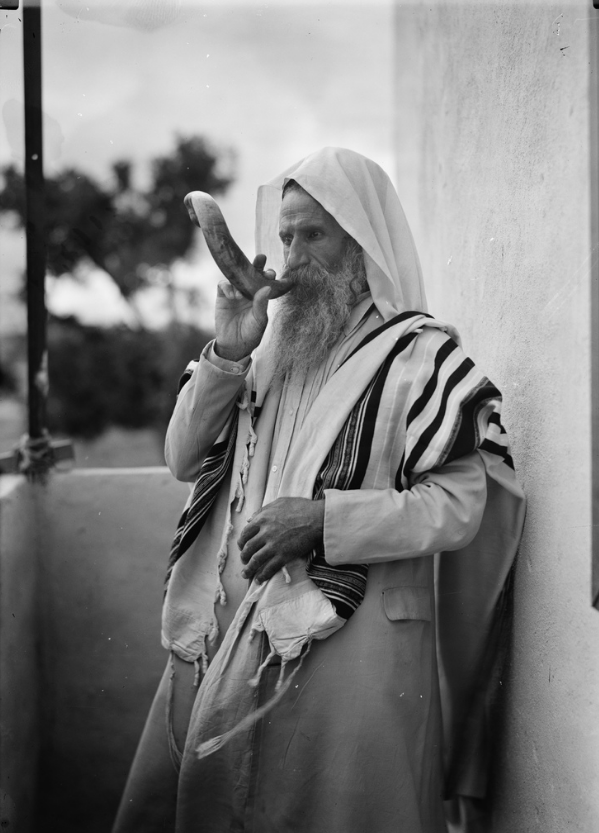

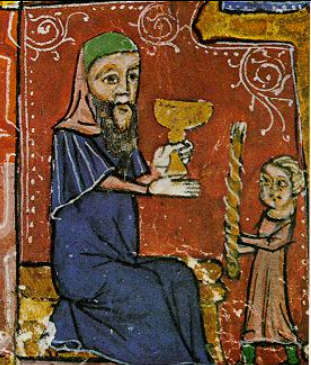

Seventh-day Sabbatarians rest on the seventh Hebrew day. Jewish Shabbat is observed from sundown on Friday until the appearance of three stars in the sky on Saturday night; it is also observed by a minority of Christians. Thirty-nine activities prohibited on Shabbat are listed in Tractate Shabbat (Talmud). Customarily, Shabbat is ushered in by lighting candles shortly before sunset, at halakhically calculated times that change from week to week and from place to place. Observance in Hebrew Scriptures was universally from sixth-day evening to seventh-day evening (Neh. 13:19, cf. Lev. 23:32) on a seven-day week; Shabbat ends approximately one hour after sunset by rabbinical ordinance to extend the Tanakh's sunset-to-sunset Sabbath into the first day of the week. The Jewish interpretation usually states that the New Covenant (Jer. 31:31) refers to the future Messianic Kingdom.

Several Christian denominations (such as Seventh Day Baptist, Seventh-day Adventist, Sabbath Rest Advent Church, Church of God (Seventh Day), and other Churches of God) observe Sabbath similarly to or less rigorously than Judaism, but observance ends at Saturday sunset instead of Saturday nightfall. Like the Jews with Shabbat, they believe that keeping seventh-day Sabbath is a moral responsibility, equal to that of any of the Ten Commandments, that honors God as Creator and Deliverer. The Christian seventh-day interpretation usually states that Sabbath belongs inherently to all nations (Ex. 20:10, Is. 56:6-7, 66:22-23) and remains part of the New Covenant after the crucifixion of Jesus (Lk. 23:56, Mt. 24:20, Acts 16:13, Heb. 8:10).[12][20] Many seventh-day Sabbatarians also use "Lord's Day" to mean the seventh day, based on Scriptures in which God calls the day "my Sabbath" (Ex. 31:13) and "to the LORD" (16:23); some count Sunday separately as Lord's Day and many consider it appropriate for communal worship (but not for first-day rest, which would be considered breaking the Ten Commandments[21]).

In this way, St. Ignatius saw believers "no longer observing the [Jewish] Sabbath, but living in the observance of the Lord's Day", and amplified this point as follows: "Let us therefore no longer keep the Sabbath after the Jewish manner, and rejoice in days of idleness .... But let every one of you keep the Sabbath after a spiritual manner, rejoicing in meditation on the law, not in relaxation of the body, admiring the workmanship of God, and not eating things prepared the day before, nor using lukewarm drinks, and walking within a prescribed space, nor finding delight in dancing and plaudits which have no sense in them. And after the observance of the Sabbath, let every friend of Christ keep the Lord's Day as a festival, the resurrection-day, the queen and chief of all the days."[19]

The Seventh-day Adventist official 28 fundamental beliefs (at 20) state:

The beneficent Creator, after the six days of Creation, rested on the seventh day and instituted the Sabbath for all people as a memorial of Creation. The fourth commandment of God's unchangeable law requires the observance of this seventh-day Sabbath as the day of rest, worship, and ministry in harmony with the teaching and practice of Jesus, the Lord of the Sabbath. The Sabbath is a day of delightful communion with God and one another. It is a symbol of our redemption in Christ, a sign of our sanctification, a token of our allegiance, and a foretaste of our eternal future in God's kingdom. The Sabbath is God's perpetual sign of His eternal covenant between Him and His people. Joyful observance of this holy time from evening to evening, sunset to sunset, is a celebration of God's creative and redemptive acts. (Gen. 2:1-3; Ex. 20:8-11; Luke 4:16; Isa. 56:5, 6; 58:13, 14; Matt. 12:1-12; Ex. 31:13-17; Eze. 20:12, 20; Deut. 5:12-15; Heb. 4:1-11; Lev. 23:32; Mark 1:32.)[22]

The Doctrinal Points of the Church of God (7th day) (Salem Conference, at 17) state:

We should observe the seventh day of the week (Saturday), from even to even, as the Sabbath of the Lord our God. Evening is at sunset when day ends and another day begins. No other day has ever been sanctified as the day of rest. The Sabbath Day begins at sundown on Friday and ends at sundown on Saturday. Genesis 2:1-3; Exodus 20:8-11; Isaiah 58:13-14; 56:1-8; Acts 17:2; Acts 18:4, 11; Luke 4:16; Mark 2:27-28; Matthew 12:10-12; Hebrews 4:1-11; Genesis 1:5, 13-14; Nehemiah 13:19.[23]

Both Jewish and Christian seventh-day interpretation usually state that Jesus' teachings relate to the Pharisaic position on Sabbath observance, and that Jesus kept seventh-day Sabbath throughout his life on earth.

Sunday law

Noticing the rise of blue laws, the Seventh-day Adventist church in particular has traditionally taught that in the end time a coalition of religious and secular authorities will enforce an international Sunday law; church pioneers saw observance of seventh-day Sabbath as a "mark" or "seal" or test of God's people that seals them, even as those who do not observe Sunday rest will be persecuted and killed. Ellen G. White interpreted Dan. 7:25, Rev. 13:15, Rev. 7, Ezek. 20:12-20, and Ex. 31:13 in this way, describing the subject of persecution in prophecy as being about Sabbath commandments.

6.2. First Day

Most Christians worship communally on the first (Hebrew or Roman) day. In most Christian denominations (Roman Catholic, some Eastern Orthodox, and most Protestant), the "Lord's Day" (Sunday) is the fulfillment of the "Sabbath" (Catholic Catechism 2175), which is kept in commemoration of the resurrection of Christ, and often celebrated with the Eucharist (Catholic Catechism 2177).[24] It is often also the day of rest. Lord's Day is considered both the first day and the "eighth day" of the seven-day week, symbolizing both first creation and new creation (2174).[24] (Alternatively, in some calendars, Sunday is designated the seventh day of the week.) Relatively few Christians regard first-day observance as entailing all of the ordinances of Shabbat. This interpretation usually states that the Holy Spirit through the Apostles instituted the worship celebration of the first day to commemorate Jesus' resurrection, and that the New Covenant transfers Sabbath-keeping (whether defined as rest or communal worship or both) to the first day by implication.[25] In Roman Catholicism, the transfer is described as based on their church's authority and papal infallibility.[26]

Roman Catholics (and many Protestants) view the first day as a day for assembly for worship (2178, Heb. 10:25),[24] but consider a day of rigorous rest not obligatory on Christians (Rom. 14:5, Col. 2:16).[27] Catholics count the prohibition of servile work as transferred from seventh-day Sabbath to Sunday (2175-6),[24][28] but do not hinder participation in "ordinary and innocent occupations".[29] Similarly, second-century father Justin Martyr believed in keeping perpetual Sabbath by repentance,[30] holding that Gentile Christians need not rest as Jews were commanded;[31] but he accepted extant non-Judaizing seventh-day Sabbatarian Christians "in all things as kinsmen and brethren".[32]

In other Protestant denominations, Lord's Day is kept as a rest day with similar rigor as Jewish Sabbath. The Westminster Confession of Faith 21:7-8, a Reformed Sabbatarian creed, states:

As it is the law of nature, that, in general, a due proportion of time be set apart for the worship of God; so, in His Word, by a positive, moral, and perpetual commandment binding all men in all ages, He has particularly appointed one day in seven, for a Sabbath, to be kept holy unto him (Ex. 20:8, 20:10-11, Is. 56:2, 56:4, 56:6-7): which, from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week: and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week (Ge. 2:2-3, 1 Cor. 16:1-2, Ac. 20:7), which, in Scripture, is called the Lord's Day (Rev. 1:10), and is to be continued to the end of the world, as the Christian Sabbath (Ex. 20:8, 20:10, Mt. 5:17). This Sabbath is to be kept holy unto the Lord when men, after a due preparing of their hearts, and ordering of their common affairs beforehand, do not only observe an holy rest all the day from their own works, words, and thoughts about their worldly employments and recreations (Ex. 20:8, 16:23, 16:25-26, 16:29-30, 31:15-17, Is. 58:13, Neh. 13:15-19, 13:21-22), but also are taken up the whole time in the public and private exercises of His worship, and in the duties of necessity and mercy (Is. 58:13).[33]

Likewise, the General Rules of the Methodist Church required "attending upon all the ordinances of God" including "the public worship of God" and prohibited "profaning the day of the Lord, either by doing ordinary work therein or by buying or selling".[34]

Assemblies

The following textual evidence for first-day assembly is usually combined with the notion that the rest day should follow the assembly day to support first-day Sabbatarianism. On the first day of the week (usually considered the day of Firstfruits), after Jesus has been raised from the dead (Mk. 16:9), he appears to Mary Magdalene, Peter, Cleopas, and others. "On the evening of that first day of the week" (Roman time), or the evening beginning the second day (Hebrew time), the resurrected Jesus appears at a meeting of ten apostles and other disciples (Jn. 20:19). The same time of the week "a week later" (NIV) or, more literally, "after eight days again" inclusive (KJV), Jesus appears to the eleven apostles and others (Jn. 20:26). After Jesus ascends (Acts 1:9), on the feast of Pentecost or Shavuot (the 50th day from Firstfruits and thus usually calculated as the first day of the week), the Spirit of God is given to the disciples, who baptize 3,000 people into the apostolic fellowship. Later, on one occasion in Troas, the early Christians meet on the first day (Hebrew) to break bread and to listen to Christian preaching (Acts 20:7). Paul also states that the churches of Corinth and Galatia should set aside donations on the first day for collection (1 Cor. 16:2). Didache 14:1 (AD 70-120?) contains an ambiguous text, translated by Roberts as, "But every Lord's day gather yourselves together, and break bread, and give thanksgiving";[35] the first clause in Greek, "κατά κυριακήν δέ κυρίου", literally means "On the Lord's of the Lord",[36] and translators supply the elided noun (e.g., "day", "commandment" (from 13:7), or "doctrine").[37] Gleason Archer regards this as clearly referring to Sunday.[38] Breaking bread may refer to Christian fellowship, agape feasts, or Eucharist (cf. Acts 2:42, 20:7). Other interpreters believe these references do not support the concept of transfer of the seventh-day rest, and some add that they do not sufficiently prove that Sunday observance was an established practice in the primitive New Testament church.

By the second century, Justin Martyr stated, "We all gather on the day of the sun" (recalling both the creation of light and the resurrection);[39] and the Epistle of Barnabas on Is. 1:13 stated the eighth-day assembly marks the resurrection and the new creation: "He is saying there: 'It is not these sabbaths of the present age that I find acceptable, but the one of my own appointment: the one that, after I have set all things at rest, is to usher in the Eighth Day, the commencement of a new world.' (And we too rejoice in celebrating the Eighth Day; because that was when Jesus rose from the dead, and showed Himself again, and ascended into heaven.)"[40]

6.3. Both Days

Ethiopian Orthodox and Eritrean Orthodox Christians (both of which are branches of Oriental Orthodoxy) distinguish between the Sabbath (seventh day) and Lord's Day (first day) and observe both. Seventh-day Adventists in several islands of the Pacific (Tonga; Western Samoa; Tokelau; Wallis & Futuna; Phoenix & Line Islands) observe Sunday as the practice on ships in the Pacific had been to change days at the 180° meridian. The islands were well to the east of this line, so the missionaries observed the Sabbath on the day sequence of the Western Hemisphere. However, the Tonga islands used the same days as New Zealand and Australia, so the missionaries were observing the seventh-day Sabbath on the day the secular authorities called Sunday.[41][42]

The International Date Line (IDL) was placed east of Tonga to align its weekdays with New Zealand and Fiji. Consequently, Tonga's time zone is UTC+13 rather than UTC−12:00, as it would be if the Date Line ran along the 180° meridian.[43] However, the SDA church observes the Sabbath as though the IDL followed the 180° meridian.

When the International Date Line was moved, islanders who had been worshiping on Sabbath were suddenly worshiping on Sunday because of a man made international treaty. After much discussion within the church, it was decided that the islanders would continue to worship on the same day as they always had, even though the name of the day had been changed from Saturday to Sunday by decree. However this situation is not without conflict.[44]

Note:

- ↑ Governments are free to select the time zone of their choice.

6.4. Unspecified Day

Non-Sabbatarians affirm human liberty not to observe a weekly rest or worship day. While keepers of weekly days usually believe in religious liberty,[45] non-Sabbatarians are particularly free to uphold Sabbath principles, or not, without limiting observance to either Saturday or Sunday. Some advocate Sabbath rest on any chosen day of the week, and some advocate Sabbath as a symbolic metaphor for rest in Christ; the concept of "Lord's Day" is usually treated as synonymous with "Sabbath". The non-Sabbatarian interpretation usually states that Jesus' obedience and the New Covenant fulfilled the laws of Sabbath, which are thus often considered abolished or abrogated.

Some of Jesus' teachings are considered as redefining the Sabbath laws of the Pharisees (Lk. 13:10-17, Jn. 5:16-18, 9:13-16). Since Jesus is understood to have fulfilled Torah (Mk. 2:28, Mt. 5:17), non-Sabbatarian Christians believe that they are not bound by Sabbath as legalists consider themselves to be. Non-Sabbatarians can thus exhibit either Christian liberty or antinomianism. On principles of religious liberty, non-Sabbatarian Jews similarly affirm their freedom not to observe Shabbat as Orthodox Jews do.

Non-Sabbatarian Christians also cite 2 Cor. 3:2-3, in which believers are compared to "a letter from Christ, the result of our ministry, written ... not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts"; this interpretation states that Christians accordingly no longer follow the Ten Commandments with dead orthodoxy ("tablets of stone"), but follow a new law written upon "tablets of human hearts". 3:7-11 adds that "if the ministry that brought death, which was engraved in letters on stone, came with glory ..., will not the ministry of the Spirit be even more glorious? .... And if what was fading away came with glory, how much greater is the glory of that which lasts!" This is interpreted as teaching that new-covenant Christians are not under the Mosaic law, and that Sabbath-keeping is not required. Further, because "love is the fulfillment of the law" (Rom. 13:10), the new-covenant "law" is considered to be based entirely upon love and to rescind Sabbath requirements.

Non-Sabbatarians who affirm that Sabbath-keeping remains for God's people (as in Heb. 4:9) often regard this as present spiritual rest and/or future heavenly rest rather than as physical weekly rest. For instance, Irenaeus saw Sabbath rest from secular affairs for one day each week as a sign of the way that Christians were called to permanently devote themselves to God[46] and an eschatological symbol.[47]

7. Interpretations

7.1. Genesis 2

Based on Genesis 2:1-4, Sabbath is considered by seventh-day Sabbatarians to be the first holy day mentioned in the Bible, with God, Adam, and Eve being the first to observe it. In order to reconcile an omnipotent God with a resting on the seventh day of Creation, the notion of active cessation from labor, rather than passive rest, has been regarded as a more consistent reading of God's activity in this passage. Non-Sabbatarians and many first-day Sabbatarians consider this passage not to have instituted observance of Sabbath, which they place as beginning with Moses and the manna. Walter Brueggemann emphasizes Sabbath is rooted in the history of the Book of Exodus.[48]

7.2. Matthew 5

Jesus' statement, "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them," is highly debated. Some non-Sabbatarians and others such as Anabaptists believe Jesus greatly reformed the Law and thus that Sabbath could only be justified if it were reaffirmed by Jesus. Antinomianism, generally regarded as a heresy, holds that, because Jesus accomplished all that was required by the law, thus "fulfilling" it, he made it unnecessary for anyone to do anything further. Strict Sabbatarians follow or expand Augustine's statement in Reply to Faustus that Jesus empowered his people to obey the law and gave additional commands that furthered its true intentions. This passage is often related to Colossians 2, from which maintenance, transference, or abolition of Sabbath are variously taught.

7.3. Colossians 2

The English Standard Version at Col. 2:16-7 ("Therefore let no one pass judgment on you in questions of food and drink, or with regard to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath. These are a shadow of the things to come, but the substance belongs to Christ.") is taken as affirming non-Sabbatarian freedom from obligations to Sabbath, whether this means only annual Sabbaths (Lev. 23:4–44)[49] or specifically weekly Sabbath (Lev. 23:1–3).[50] This passage's threefold categorization of events is parallel to Num. 28-29, 1 Chr. 23:31, 2 Chr. 2:4, Is. 1:13, Ezek. 45:17 (Lev. 23 mentions Sabbaths and festivals but not new moons). Accordingly, non-Sabbatarians and some first-day Sabbatarians believe this passage indicates Sabbath-keeping is part of an Old Covenant that is not mandatory (cf. Heb. 8:13). Seventh-day Sabbatarians and strict first-day Sabbatarians believe this passage indicates that weekly Sabbath remains to be kept as a shadow of things future to Paul's day[51] and/or a memorial of creation past.[49]

Additionally, Col. 2:13-5 states, "And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses, by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross. He disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, by triumphing over them in him." The ESV footnote regards "in it (that is, the cross)" as equivalent to the closing in him (Christ). First-day Sabbatarians and non-Sabbatarians often regard Sabbath as changed, either to Lord's Day or to spiritual Sabbath, by the Mosaic law being the "record of debt" (ESV) nailed to the cross. Some seventh-day Sabbatarians regard only High Sabbaths as abolished due to their foreshadowing the cross, holding it impossible for weekly Sabbath (which preceded sin) to foreshadow deliverance from sin in the cross.[17] Others see the "record of debt" (accusations) as distinct from God's unchanging law, believing it to be in force and affirmed by the evangelists after Jesus died on the cross,[12] regarding Sabbath, new moon, and High Sabbaths not as nailed to the cross but as foreshadowing the eternal plan of God.[18]

7.4. Hebrews 4

The unique word sabbatismos in Hebrews 4:9 is translated "rest" in the Authorized Version and others; "Sabbath rest" in the New International Version and other modern translations; "Sabbatism" (a transliteration) in the Darby Bible; "Sabbath observance" in the Scriptures 98 Edition; and "Sabbath keeping" in the Bible in Basic English. The word also appears in Plutarch, De Superstitione 3 (Moralia 166A); Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 23:3; Epiphanius, Adversus Haereses 30:2:2; Martyrium Petri et Pauli 1; and Apostolic Constitutions 2:36:2. Andrew Lincoln states, "In each of these places the term denotes the observance or celebration of the Sabbath .... Thus the writer to the Hebrews is saying that since the time of Joshua an observance of the Sabbath rest has been outstanding."[52] Sabbatarians believe the primary abiding Christian duty intended is weekly Sabbath-keeping, while non-Sabbatarians believe it is spiritual or eschatological Sabbath-keeping; both meanings may be intended. Justin uses sabbatismos in Trypho 23:3 to mean weekly Sabbath-keeping.

However, Justin does not speak of Hebrews 4, instead holding that there is no longer any need for weekly Sabbath-keeping for anyone. Hippolytus of Rome, in the early third century, interpreted the term in Hebrews 4 to have special reference to a millennial Sabbath kingdom after six millennia of labor. St. Chrysostom interpreted the term as having reference to three rests: God's rest from His labor on the seventh day, the rest of the Israelites in arriving in Canaan, and the heavenly (eschatological) rest for the faithful. He argued that the "rest" that "has been outstanding" is the heavenly rest, since the first two rests had already been going on. He also interpreted weekly Sabbath as a symbol of this heavenly rest: "And well did he conclude the argument. For he said not rest but 'Sabbath-keeping'; calling the kingdom 'Sabbath-keeping,' by the appropriate name, and that which they rejoiced in and were attracted by. For as, on the Sabbath He commands to abstain from all evil things; and that those things only which relate to the Service of God should be done, which things the Priests were wont to accomplish, and whatsoever profits the soul, and nothing else; so also [will it be] then."[53]

Matthew Henry calls this "a rest of grace, and comfort, and holiness, in the gospel state. And a rest in glory, where the people of God shall enjoy the end of their faith, and the object of all their desires .... undoubtedly the heavenly rest, which remains to the people of God, and is opposed to a state of labour and trouble in this world. It is the rest they shall obtain when the Lord Jesus shall appear from heaven .... God has always declared man's rest to be in him, and his love to be the only real happiness of the soul."[54] This is taken to support the belief that Sabbath-keeping is a metaphor for the eternal "rest" that Christians enjoy in Christ, prefigured by the promised land of Canaan.

7.5. Hebrews 8

Non-Sabbatarians and some first-day Sabbatarians believe Hebrews 8 indicates Sabbath-keeping is not mandatory, because "in that he saith, a new covenant, he hath made the first old" (Heb. 8:13 KJV; or "obsolete" NIV). Seventh-day Sabbatarians and strict first-day Sabbatarians believe Hebrews 8 indicates the Law of God (including Sabbath) remains on the hearts of God's people to be kept, but not fallibly as in the older covenant (Heb. 8:9–10).

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Biblical_Sabbath

References

- שַׁבָּת, Strong's Concordance number 7676 as šabbāt, now usually Shabbat

- Shabbethay, "restful", 7678

- Pinches, T.G. (2003). "Sabbath (Babylonian)". in Hastings, James. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 889–891. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=qVNqXDz4CE8C. Retrieved 2009-03-17. It has been argued that the association of the number seven with creation itself derives from the circumstance that the Enuma Elish was recorded on seven tablets. "emphasized by Professor Barton, who says: 'Each account is arranged in a series of sevens, the Babylonian in seven tablets, the Hebrew in seven days. Each of them places the creation of man in the sixth division of its series." Albert T. Clay, The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel, 1923, p. 74.

- 4521

- 7677

- 4520

- "Sabbatical Year: every seventh year, during which the land, according to the law of Moses, had to remain uncultivated (Lev. 25:2-7; comp. Ex. 23:10, 11, 12; Lev. 26:34, 35). Whatever grew of itself during that year was not for the owner of the land, but for the poor and the stranger and the beasts of the field." Easton's Bible Dictionary, 1897.

- Dabney, Robert L. "The Christian Sabbath: Its Nature, Design and Proper Observance". Discussions of Robert L. Dabney. 1. Center for Reformed Theology and Apologetics. pp. 497–8. http://www.reformed.org/master/index.html?mainframe=/ethics/sabbath/sabbath_Dabney.html.

- Lincoln, Prof. Andrew T. (1982). "Sabbath, rest and eschatology in the New Testament". in Carson, D. A.. From Sabbath to Lord's Day. Zondervan. pp. 197–220.

- Edwards, Jonathan. First Sermon: The Perpetuity of the Sabbath. http://www.westminsterconfession.org/worship/perpetuity-and-change-of-the-sabbath.php. "After the Christian dispensation was fully set up .... even then Christians were bound to a strict observation of the sabbath."

- "The Sabbath and the Gospels". Sabbath in the Bible. World's Last Chance. 2004–2012. http://www.worldslastchance.com/biblical-christian-beliefs/sabbath-in-the-bible.html.

- Wohlberg, Steve. "Sabbath Basics". http://www.whitehorsemedia.com/articles/?d=81. "Ten Reasons why the Sabbath is not Jewish". Truth Left Behind. http://www.whitehorsemedia.com/articles/?d=85.

- "Mark 16:9". Oxford NIV Scofield Study Bible. Scofield, C.I., ed.; English, E. Schuyler, chmn. New York City: Oxford University Press. 1984 [1909]. p. 1047. https://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/New%20York%20City

- "Sunday". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14335a.htm. "The practice of meeting together on the first day of the week for the celebration of the Eucharistic Sacrifice is indicated."

- Richards, H.M.S. (1940). Hard Nuts Cracked. p. 6. http://www.sabbathtruth.com/faq/arguments-refuted/articletype/articleview/articleid/1026/if-the-early-christians-kept-sabbath-.aspx. "After all there is nothing in the Scriptures to show that the celebration of the Lord's Supper was confined to any particular day of the week." Cf. Acts 2:46.

- Stern, David H. (1992). "Notes on Gal. 4:8-10". Jewish New Testament Commentary. Clarksville, Maryland: Jewish New Testament Publications, Inc.. p. 557. ISBN 965-359-008-1. "When Gentiles observe these Jewish holidays ... out of fear induced by Judaizers who have convinced them that unless they do these things, God will not accept them, then they are not obeying the Torah but subjugating themselves to legalism .... An alternative interpretation, however, is that the 'days, months, seasons and years' of this passage do not refer to the Jewish holidays at all but to pagan Gentile feasts, naturally and directly reflecting 'those weak and miserable elemental spirits.' According to this understanding Sha'ul was worried that his ex-pagan converts might be returning to these pagan festivals."

- "6. Doesn't Colossians 2:14-17 do away with the seventh-day Sabbath?". The Lost Day Of History. Amazing Facts. 2010. http://www.sabbathtruth.com/faq/advanced-topics/the-lost-day-of-history.aspx.

- Howard, Kevin (1997). The Feasts of the Lord. Zion's Hope. pp. 224. ISBN 978-0-7852-7518-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=YTCsOwAACAAJ&dq=the+feasts+of+the+lord&hl=en&ei=thPjTseeM8TetgePvqHoAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CEoQ6AEwAA.

- St. Ignatius. Epistle to the Magnesians. 9. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.v.iii.ix.html.

- "8. But wasn't the Sabbath changed to Sunday at Christ's death or resurrection?". The Lost Day Of History. Amazing Facts. 2010. http://www.sabbathtruth.com/faq/advanced-topics/the-lost-day-of-history.aspx.

- Wohlberg, Steve. "Anti-Sabbath Arguments: Are They Really Right?". Truth Left Behind. http://www.whitehorsemedia.com/articles/?d=81.

- Fundamental Beliefs. 20. http://www.adventist.org/beliefs/fundamental/index.html.

- "Doctrinal Points of the Church of God (7th Day)". Salem, West Virginia: The Church of God Publishing House. p. 18. http://www.churchofgod-7thday.org/Publications/Doctrinal%20Points%20Final%20Proof.pdf.

- United States Catholic Conference, Inc. (1997). "You Shall Love the Lord Your God with All Your Heart, and with All Your Soul, and with All Your Mind, Article 3, The Third Commandment (2168-2195)". Catechism of the Catholic Church (2d ed.). New York City: Doubleday. pp. 580–6. https://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/New%20York%20City

- James Cardinal Gibbons, The Faith of Our Fathers (1917 edition), p. 72-73 (16th Edition, p. 111; 88th Edition, p. 89). "You may read the Bible from Genesis to Revelation, and you will not find a single line authorizing the sanctification of Sunday. The Scriptures enforce the religious observance of Saturday, a day which we never sanctify."

- Catholic Virginian, October 3, 1947, p. 9, article "To Tell You the Truth." "For example, nowhere in the Bible do we find that Christ or the Apostles ordered that the Sabbath be changed from Saturday to Sunday. We have the commandment of God given to Moses to keep holy the Sabbath day, that is the 7th day of the week, Saturday. Today most Christians keep Sunday because it has been revealed to us by the [Roman Catholic] church outside the Bible."

- "Sabbath". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13287b.htm.

- "Ten Commandments". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13287a.htm.

- "Sabbatarians". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13287a.htm.

- Justin Martyr. Dialogue with Trypho. 12. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.viii.iv.xii.html.

- Justin Martyr. Dialogue with Trypho. 23. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.viii.iv.xxiii.html.

- Justin Martyr. Dialogue with Trypho. 47. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.viii.iv.xlvii.html.

- Westminster Confession of Faith. 21.7-8. http://www.reformed.org/documents/wcf_with_proofs/.

- Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield (27 April 2011) (in English). American Methodist Worship. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780199774159.

- "14:1". Didache. Roberts, trans. Early Christian Writings. http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/didache-roberts.html.

- Holmes, M. The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations.

- Strand, Kenneth A. (1982). The Sabbath in Scripture and History. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association. pp. 347–8. In Morgan, Kevin (2002). Sabbath Rest. TEACH Services, Inc.. pp. 37–8.

- Archer, Gleason L. An Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties. p. 114. http://www.tsbalan.com/books/Difficulties.pdf.

- Justin Martyr. First Apology. 67.

- Epistle of Barnabas. 15. Staniforth, Maxwell, trans.

- Hay 1990, p. 4.

- Governments are free to select the time zone of their choice.

- Greene 2002, p. 80.

- [1]

- Berkowitz, Richard & Michele (1991). Shabbat. Baltimore: Lederer Publications. pp. 11–2. ISBN 1-880226-00-6. "We have a remembrance–a physical Sabbath day–to remind us anew of our spiritual freedom in him .... Observance paints a sacred picture of what it is like to be united in faith with Messiah Yeshua. One other reason to observe Shabbat is God has a blessing for us."

- Against Heresies. 3.16.1. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.ix.vi.xvii.html.

- Against Heresies. 4.33.2. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.ix.vii.xxxiv.html.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). The Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith. Overtures to Biblical Theology (2d ed.). Fortress Press. pp. 60, 225. ISBN 978-0-8006-3462-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=gFQQAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2011-09-28. "The tradition of Deuteronomy appeals for Sabbath on more historical grounds. Sabbath is rooted in the history of Exodus, which led to the land of fulfillment."

- Walker, Allen. "Please explain Colossians 2:14". The Law and the Sabbath. pp. 113–116. http://www.sabbathtruth.com/faq/frequently-asked-questions/articletype/articleview/articleid/929/please-explain-colossians-214.aspx.

- "Notes on Col. 2:16-7". Holy Bible, English Standard Version. "The false teacher(s) were advocating a number of Jewish observances, arguing that they were essential for spiritual advancement .... The old covenant observances pointed to a future reality that was fulfilled in the Lord Jesus Christ (cf. Heb. 10:1). Hence, Christians are no longer under the Mosaic covenant (cf. Rom. 6:14–15; 7:1–6; 2 Cor. 3:4–18; Gal. 3:15–4:7). Christians are no longer obligated to observe OT dietary laws ('food and drink') or festivals, holidays, and special days ('a festival ... new moon ... Sabbath,' Col. 2:16), for what these things foreshadowed has been fulfilled in Christ. It is debated whether the Sabbaths in question included the regular seventh-day rest of the fourth commandment, or were only the special Sabbaths of the Jewish festal calendar."

- Stern, David H. (1992). "Notes on Col. 2:17". Jewish New Testament Commentary. Clarksville, Maryland: Jewish New Testament Publications, Inc.. p. 611. ISBN 965-359-008-1. "These are a shadow of things that are coming, meaning the good things that will happen when Yeshua returns." Both verbs in 17a are present tense.

- Lincoln, Prof. Andrew T. "From Sabbath to Lord's Day (symposium)". p. 213.

- John Chrysostom. "6th Homily on the Epistle to the Hebrews". http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf114.v.x.html.

- Henry, Matthew. Concise Commentary on the Whole Bible.