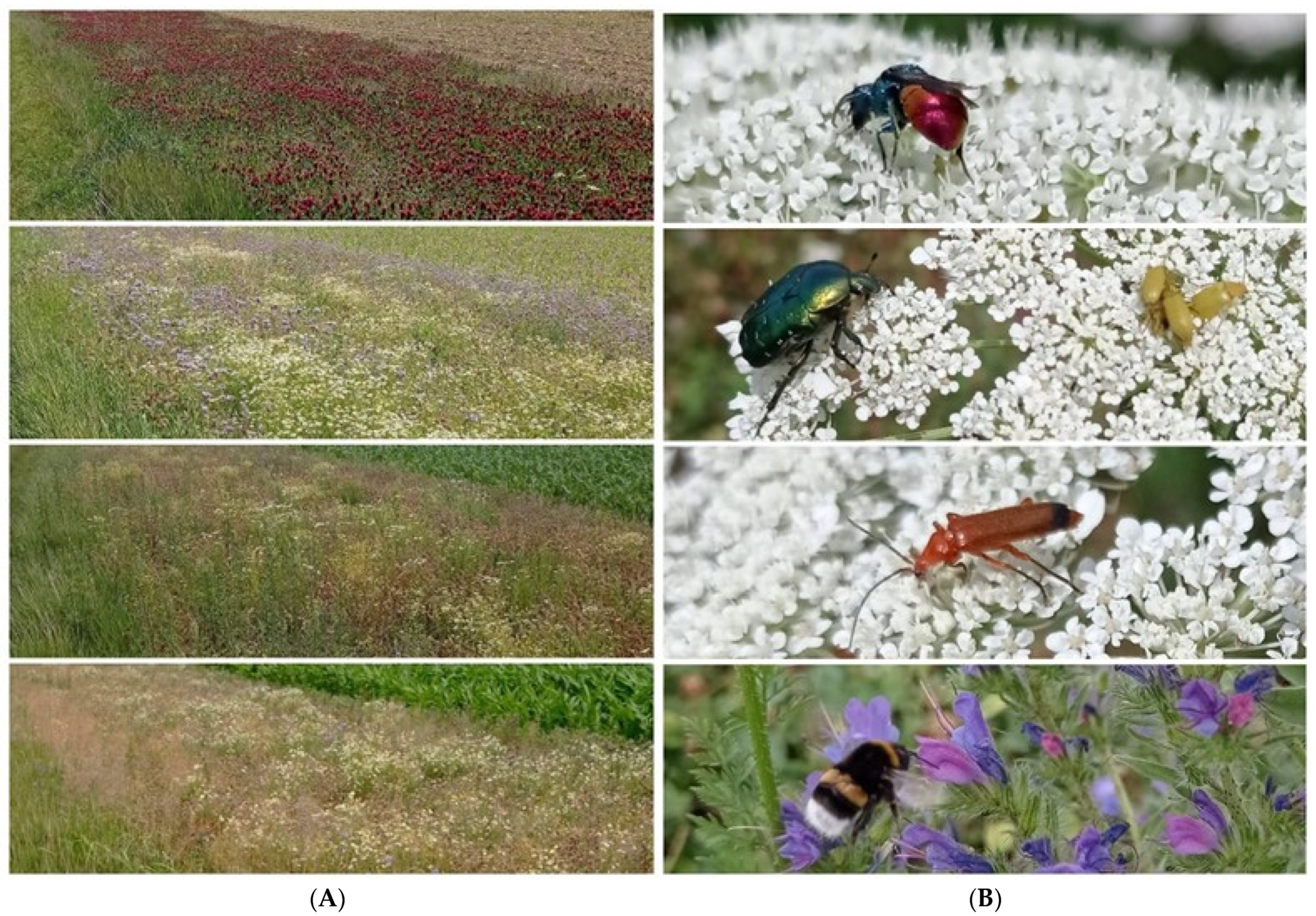

Wildflower strips, a semi-natural manmade habitat comprising mixtures of native herbaceous species, can be sown on arable field margins to provide multiple ecological, agricultural and conservation benefits. The main aim of creating flower strips is to enrich the fauna of farmland with the species that are beneficial in terms of the agricultural economy: animals that limit the population density of pests (e.g., parasitic insects, including parasitoids, predatory insects and spiders and birds) and pollinators (insects that feed on pollen or nectar), including those with economic significance. For this reason, flower strips should be included in agri-environmental programs to enhance sustainable plant production and the biodiversity of pollinators on farmland or natural aphid enemies. Flower strips are thus increasingly frequently promoted in environmental programmes, and financial support is being implemented as an additional business incentive.

- beneficial macro-organisms

- biodiversity

- Flower Strips

1. Species Composition

2. Types of Flower Strips

2.1. Annual Flower Strips

2.2. Perennial Flower Strips

3. Width of Flower Strips

4. Weeds on Flower Strips

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agriculture12091470

References

- Pfiffner, L.; Wyss, E. Use of sown wildflower strips to enhance natural enemies of agricultural pests. In Ecological Engineering for Pest Management: Advances in Habitat Manipulation for Arthropods; Gurr, G.M., Wratten, S.D., Altieri, M.A., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2004; pp. 165–186.

- Kujawa, K.; Bernacki, Z.; Arczyńska-Chudy, E.; Janku, K.; Karg, J.; Kowalska, J.; Oleszczuk, M.; Sienkiewicz, P.; Sobczyk, D.; Weyssenhoff, D. Kwietne pasy: Rzadko stosowane w Polsce narzędzie wzmacniania integrowanej ochrony roślin uprawnych oraz zwiększania różnorodności biologicznej na terenach rolniczych. Prog. Plant Prot. 2018, 58, 115–128.

- Tschumi, M.; Albrecht, M.; Bärtschi, C.; Collatz, J.; Entling, M.H.; Jacot, K. Perennial, species-rich wildflower strips enhance pest control and crop yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 220, 97–103.

- Pontin, D.; Wade, M.; Kehrli, P.; Wratten, S. Attractiveness of single and multiple species flower patches to beneficial insects in agroecosystems. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2006, 148, 39–47.

- Haaland, C.; Gyllin, M. Butterflies and bumblebees in greenways and sown wildflower strips in southern Sweden. J. Insect Conserv. 2010, 14, 125–132.

- Baden-Böhm, F.; Thiele, J.; Dauber, J. Response of honeybee colony size to flower strips in agricultural landscapes depends on areal proportion, spatial distribution and plant composition. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2022, 60, 123–138.

- Tschumi, M.; Albrecht, M.; Collatz, J.; Dubsky, V.; Entling, M.H.; Najar-Rodriguez, A.J.; Jacot, K. Tailored flower strips promote natural enemy biodiversity and pest control in potato crops. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 1169–1176.

- Amy, C.; Noël, G.; Hatt, S.; Uyttenbroeck, R.; Van de Meutter, F.; Genoud, D.; Francis, F. Flower Strips in Wheat Intercropping System: Effect on Pollinator Abundance and Diversity in Belgium. Insects 2018, 9, 114.

- Brandt, K.; Glemnitz, M.; Schröder, B. The impact of crop parameters and surrounding habitats on different pollinator group abundance on agricultural fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 243, 55–66.

- Azpiazu, C.; Medina, P.; Adán, Á.; Sánchez-Ramos, I.; Del Estal, P.; Fereres, A.; Vinuela, E. The Role of Annual Flowering Plant Strips on a Melon Crop in Central Spain. Influence on Pollinators and Crop. Insects 2020, 11, 66.

- Montero-Castano, A.; Ortiz-Sánchez, F.J.; Vila, M. Mass flowering crops in a patchy agricultural landscape can reduce bee abundance in adjacent shrublands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 223, 22–30.

- Kujawa, K.; Bernacki, Z.; Kowalska, J.; Kujawa, A.; Oleszczuk, M.; Sienkiewicz, P.; Sobczyk, D. Annual Wildflower Strips as a Tool for Enhancing Functional Biodiversity in Rye Fields in an Organic Cultivation System. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1696.

- Tschumi, M.; Albrecht, M.; Entling, M.H.; Jacot, K. High effectiveness of tailored flower strips in reducing pests and crop plant damage. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282, 20151369.

- Haenke, S.; Scheid, B.; Schaefer, M.; Tscharntke, T. Increasing syrphid fly diversity and density in sown flower strips within simple vs. complex landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 1106–1114.

- Nilsson, L.; Klatt, B.K.; Smith, H.G. Effects of Flower-Enriched Ecological Focus Areas on Functional Diversity Across Scales. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2009, 9, 629124.

- Klatt, B.K.; Nilsson, L.; Smith, H.G. Annual flowers strips benefit bumble bee colony growth and reproduction. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 252, 108814.

- Boetzl, F.A.; Krimmer, E.; Krauss, J.; Stean-Dewenter, I. Agri-environmental schemes promote ground-dwelling predators in adjacent oilseed rape fields: Diversity, species traits and distance-decay functions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 10–20.

- Schoch, K.; Tschumi, M.; Lutter, S.; Ramseier, H.; Zingg, S. Competition and Facilitation Effects of Semi-Natural Habitats Drive Total Insect and Pollinator Abundance in Flower Strips. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 854058.

- Raderschall, C.A.; Lundin, O.; Lindström, S.A.M.; Bommarco, R. Annual flower strips and honeybee hive supplementation differently affect arthropod guilds and ecosystem services in a mass-flowering crop. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107754.

- Ganser, D.; Knop, E.; Albrecht, M. Sown wildflower strips as overwintering habitat for arthropods: Effective measure or ecological trap? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 275, 123–131.

- Bommarco, R.; Lindström, S.A.M.; Raderschall, C.A.; Gagic, V.; Lundin, O. Flower strips enhance abundance of bumble bee queens and males in landscapes with few honey bee hives. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 263, 109363.

- Jacobsen, S.K.; Sørensen, H.; Sigsgaard, L. Perennial flower strips in apple orchards promote natural enemies in their proximity. Crop Prot. 2022, 156, 105962.

- Corbet, S.A. Insects, plants and succession: Advantages of long-term set-aside. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1995, 53, 201–2017.

- Ullrich, K. The Influence of Wildflower Strips on Plant and Insect (Hetroptera) Diversity in Anarable Landscape. Ph.D. Thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zürich, Switzerland, 2001.

- Buhk, C.; Oppermann, R.; Schanowski, A.; Schanowski, A.; Bleil, R.; Ludemann, J.; Maus, C. Flower strip networks offer promising long term effects on pollinator species richness in intensively cultivated agricultural areas. BMC Ecol. 2018, 18, 55.

- Schmidt, A.; Kirmer, A.; Kiehl, K.; Tischew, S. Seed mixture strongly affects species-richness and quality of perennial flower strips on fertile soil. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2020, 42, 62–72.

- Albrecht, M.; Kleijn, D.; Williams, N.M.; Tschumi, M.; Blaauw, B.R.; Bommarco, R.; Campbell, A.J.; Dainese, M.; Drummond, F.A.; Entling, M.H.; et al. The effectiveness of flower strips and hedgerows on pest control, pollination services and crop yield: A quantitative synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 23, 1488–1498.

- Wix, N.; Reich, M.; Schaarschmidt, F. Butterfly richness and abundance in flower strips and field margins: The role of local habitat quality and landscape context. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01636.

- Hatt, S.; Uyttenbroeck, R.; Lopes, T.; Mouchon, P.; Chen, J.; Piqueray, J.; Monty, A.; Francis, F. Do flower mixtures with high functional diversity enhance aphid predators in wildflower strips? Eur. J. Entomol. 2017, 114, 66–76.

- Ditner, N.; Balmer, O.; Beck, J.; Blick, T.; Nagel, P.; Luka, H. Effects of experimentally planting non-crop flowers into cabbage fields on the abundance and diversity of predators. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 1049–1061.

- Agro Profil. Magazyn Rolniczy. Available online: https://agroprofil.pl/wiadomosci/jakwplywana-uprawe-maja-pasy-kwietne-dane-zaskakuja (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A. Plant biodiversity enhances bees and other insect pollinators in agroecosystems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 257–274.

- Bretagnolle, V.; Gaba, S. Weeds for bees? A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 891–909.

- Rollin, O.; Benelli, G.; Benvenuti, S.; Decourtye, A.; Wratten, S.D.; Canale, A.; Desneux, N. Weed-insect pollinator networks as bio-indicators of ecological sustainability in agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 8.

- Rollin, O.; Bretagnolle, V.; Decourtye, A.; Aptel, J.; Michel, N.; Vaissiere, B.E.; Mickael, H. Differences of floral resource use between honey bees and wild bees in an intensive farming system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 179, 78–86.

- Molthan, J.; Ruppert, V. Significance of flowering wild herbs in boundary strips and fields for flower-visiting beneficial insects. Mitt. Biol. Buden. Land. Fortst. 1988, 247, 85–99.