Pseudo-reorganization acquisitions are acquisitions that are done in order to repatriate income earned by foreign subsidiaries to a parent corporation while avoiding taxes ordinarily owed on the repatriation of foreign income in countries with a worldwide system of taxation. Prior to the passage of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017, multinational firms based in the United States avoided taxes on the repatriation of income earned abroad through the use of pseudo-reorganization acquisitions.

- foreign subsidiaries

- pseudo-reorganization

- multinational firms

1. Background

Until the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, international firms based in the United States owed the federal government taxes on income earned worldwide.[1][2] However, rather than collecting taxes during the year the income was earned, the United States only required companies to pay taxes on earnings that had been repatriated to the United States.[3][4] During this time, companies employed strategies to repatriate some of their income from overseas while avoiding tax liabilities ordinarily associated with foreign earnings repatriation. Several strategies to avoid owing repatriation taxes to the United States government involved the creative use of mergers and acquisitions.[3][4][5] The cost associated with repatriating income is not consistent across firms, and there is an association between the tax cost of repatriating foreign income to the United States and the probability that a firm will choose to make a domestic acquisition.[4]

2. Strategies

2.1. United States

Numerous strategies have been employed by firms based in the United States in order to reduce their taxes owed through the use of pseudo-reorganization acquisitions.[5][6][7] These include acquisition strategies known as the "Killer B", "Deadly D", and "Outbound F".[5][6][7][8][9][10]

These three strategies facilitate tax avoidance through careful planning of transactions; a U.S.-based multinational corporation does not technically repatriate foreign profits when it performs a pseudo-reorganization acquisition.[6][7] Instead, a company performs a set of transactions that are classified as a "reorganization" under Section 368(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code.[4][7] The advantage of performing these transactions is that such "reorganizations" are not taxed.[4][5][6] However, companies structure these reorganization so as to, from an economic perspective, move cash from foreign subsidiaries into the United States while financing a corporate acquisition, thereby avoiding the tax on repatriated profits that they would ordinarily have to pay if a company were to directly repatriate the profits.[4][5][6][9]

Definition of Reorganizations under Internal Revenue Code Section 368(a)(1)

Section 368(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code states that a "reorganization" is defined as:[11]

(A) a statutory merger or consolidation;(B) the acquisition by one corporation, in exchange solely for all or a part of its voting stock (or in exchange solely for all or a part of the voting stock of a corporation which is in control of the acquiring corporation), of stock of another corporation if, immediately after the acquisition, the acquiring corporation has control of such other corporation (whether or not such acquiring corporation had control immediately before the acquisition);

(C) the acquisition by one corporation, in exchange solely for all or a part of its voting stock (or in exchange solely for all or a part of the voting stock of a corporation which is in control of the acquiring corporation), of substantially all of the properties of another corporation, but in determining whether the exchange is solely for stock the assumption by the acquiring corporation of a liability of the other shall be disregarded;

(D) a transfer by a corporation of all or a part of its assets to another corporation if immediately after the transfer the transferor, or one or more of its shareholders (including persons who were shareholders immediately before the transfer), or any combination thereof, is in control of the corporation to which the assets are transferred; but only if, in pursuance of the plan, stock or securities of the corporation to which the assets are transferred are distributed in a transaction which qualifies under section 354, 355, or 356;

(E) a recapitalization;

(F) a mere change in identity, form, or place of organization of one corporation, however effected; or

(G) a transfer by a corporation of all or part of its assets to another corporation in a title 11 or similar case; but only if, in pursuance of the plan, stock or securities of the corporation to which the assets are transferred are distributed in a transaction which qualifies under section 354, 355, or 356.

The definition of this section of the Internal Revenue Code has enabled for multinational corporations to classify certain types of acquisitions as tax-exempt corporate reorganizations, allowing companies to repatriate income earned abroad tax-free when that income is used to finance a pseudo-reorganization acquisition.[3][5][6]

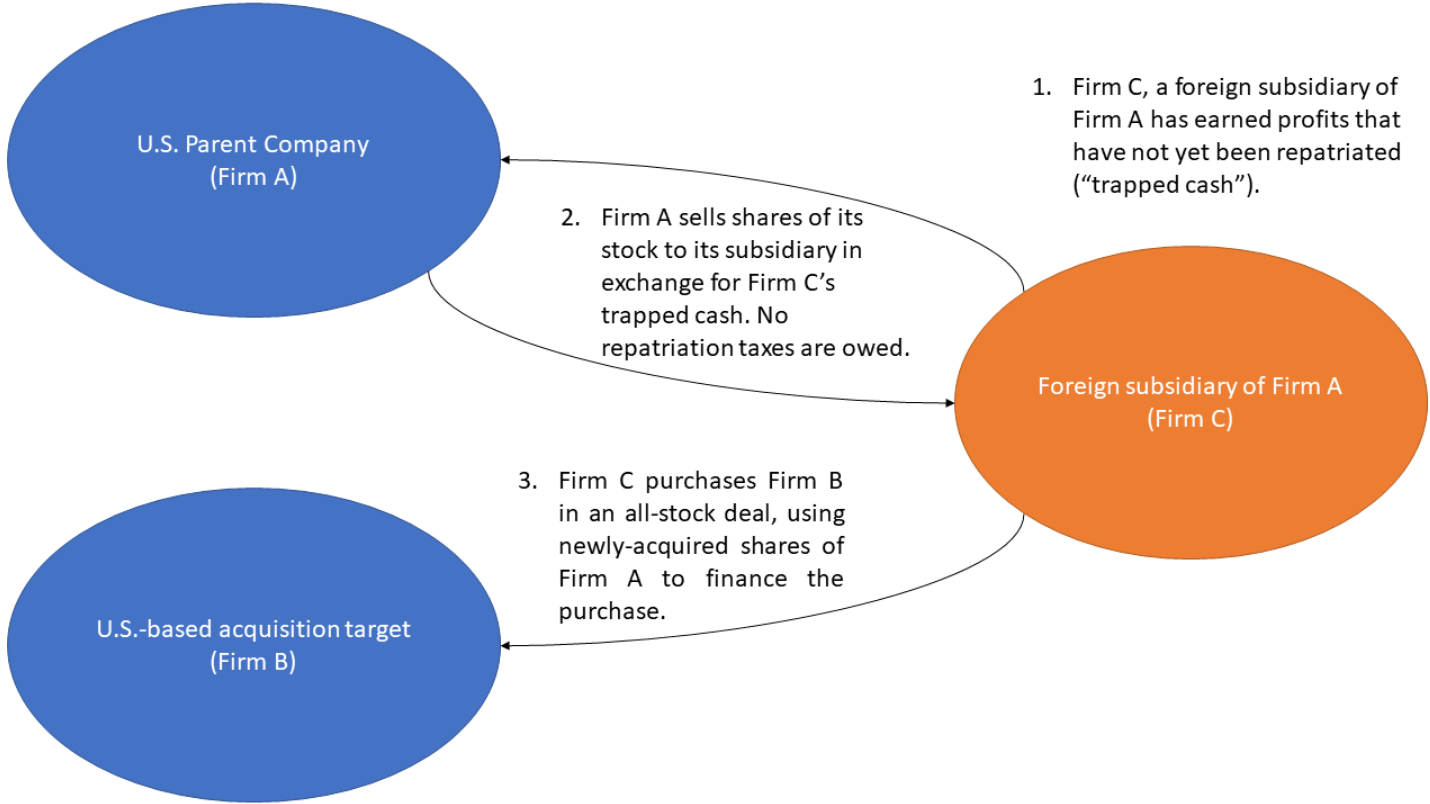

Killer B

The "Killer B" strategy is a tax-avoidance strategy that reduces a firm's taxes owed on the repatriation of foreign cash used in the acquisition of another firm through the classification of an acquisition as a reorganization provided by Section 368(a)(1)(B) of the Internal Revenue Code.[5][6][7][12] The use of this strategy requires the creation of an arrangement in which the parent corporation provides stock to a foreign subsidiary in exchange for cash,[12] with the subsidiary then using the stock to acquire another company.[5][7][13] This cash transferred from the foreign subsidiary to the parent company would be exempt from taxation.[5][7][12] According to a 2011 report, the Internal Revenue Service had gained increasing success in disallowing the use of this tax avoidance strategy since 2006.[13]

Deadly D

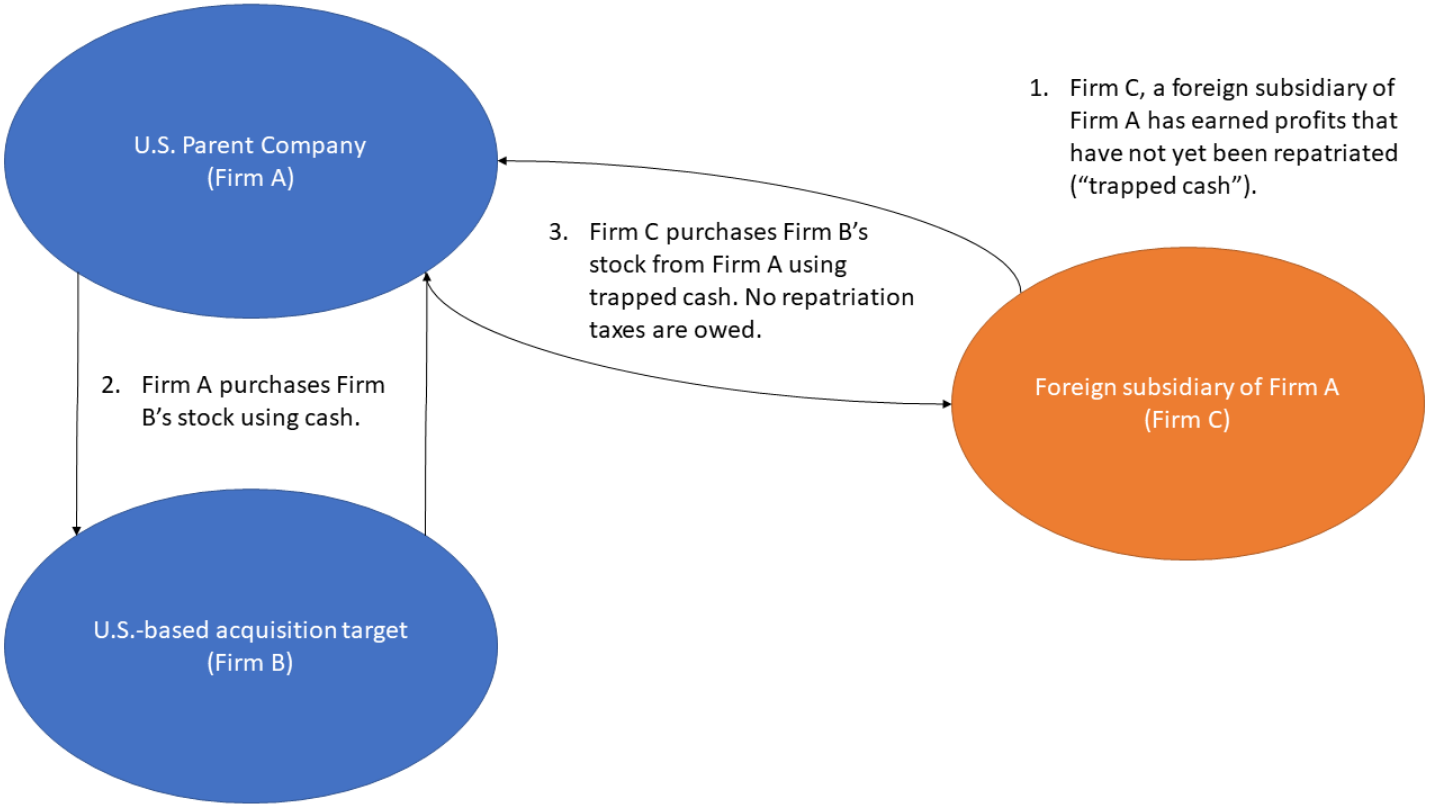

The "Deadly D" strategy is a tax-avoidance strategy that utilizes Section 368(a)(1)(D) of the Internal Revenue code in order to reduce a firm's taxes owed on the repatriation of foreign cash used in the acquisition of another firm.[12][13] In order to use this strategy, a parent corporation must first directly acquire a corporation, and then sell the ownership of the newly acquired corporation to a foreign subsidiary in exchange for cash.[7][12][13] This allows for foreign cash to be effectively used to finance the acquisition of the newly acquired company without the parent corporation incurring tax liability on the repatriation of that cash.[5][7][12][13]

Outbound F

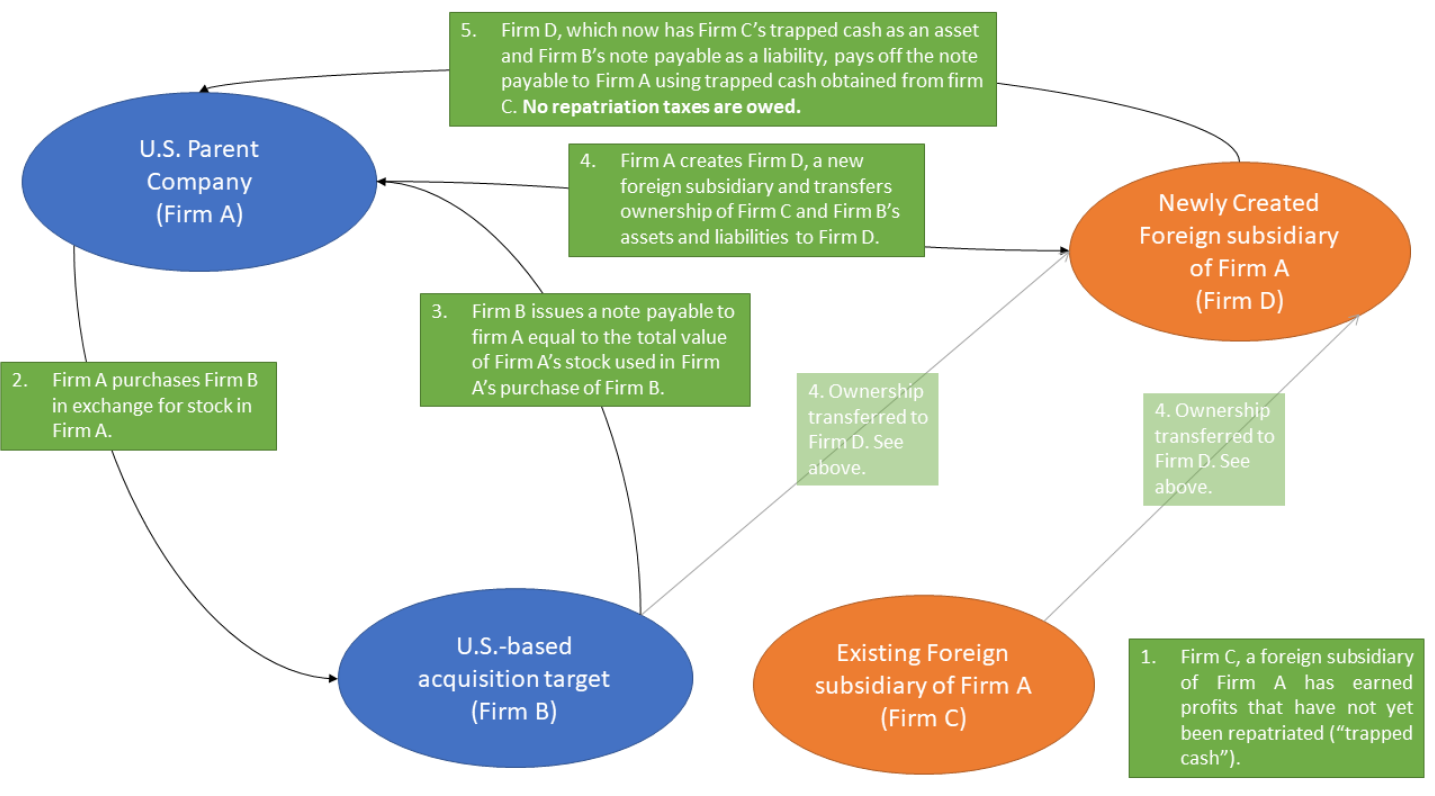

The "Outbound F" strategy is a tax-avoidance strategy that utilizes Section Section 368(a)(1)(F) of the Internal Revenue code in order to repatriate foreign-earned income without incurring taxes owed.[5][7][13][14] This strategy is a multi-step process that begins when the parent company acquires another company by purchasing it with stock and then forces the newly acquired company to post a bond to the parent itself.[5][7][12] Next, the newly acquired company is transformed into a foreign subsidiary of the parent corporation, which then borrows money from other foreign-owned subsidiaries of the parent company in order to pay off the bond posted.[5][7][12][13] This allows for the effective repatriation of cash up to the amount of the sum of the bond's principle and interest to be done without incurring tax liability.[4][5][7][12][13]

3. Examples of Pseudo-reorganization Acquisitions

The tax advantages of pseudo-reorganization acquisitions for multinational corporations are widely known and have been utilized by several multinationals to avoid repatriation taxes.[5][6][7] Each of the Big Four accounting firms have created public presentations describing the mechanisms of pseudo-reorganization acquisitions and the steps needed to implement them.[7]

3.1. Merck & Co.'s Acquisition of Schering-Plough

In 2009, Merck & Co. used a variation of the Outbound F pseudo-reorganization acquisition technique in order to move over $9 billion from overseas into the United States without owing repatriation taxes during its purchase of Schering-Plough.[4][5][6][7] As a part of the deal foreign subsidiaries owned by Merck lent money to subsidiaries of Schering-Plough, which in turn used the funds to repay a loan owed by the subsidiaries of Schering-Plough to the parent corporation.[4][5] As the parent corporation of Schering-Plough was acquired by Merck & Co., this amounted to the effective repatriation of overseas cash by Merck & Co. for use in an acquisition without owing repatriation taxes to the United States.[4][5][6][7][15]

3.2. Johnson & Johnson's Acquisition of Synthes

In 2012, Johnson & Johnson (J&J) acquired Synthes in a cash-and-stock deal that involved the use of pseudo-reorganization acquisition techniques.[4][6][16] The Wall Street Journal reports that, two days prior to the acquisition closing, "J&J unveiled a complicated new structure for the cash and stock deal. Its Irish subsidiary, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., paid for Synthes with J&J's untaxed foreign cash holdings. Then, by transferring Synthes into another of J&J's foreign subsidiaries and dissolving Synthes before the end of the quarter, the pharmaceutical giant escaped the tax hit, according to a person familiar with the deal."[16] Six weeks after the acquisition closed, the Internal Revenue Service issued an rule described as an "anti-abuse rule" that was designed to make similar tax avoidance techniques more difficult to use going forward.[4][16]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Finance:Pseudo-reorganization_acquisitions

References

- "Territorial Tax System". https://taxfoundation.org/tax-basics/territorial-taxation/.

- "Worldwide Tax System". https://taxfoundation.org/tax-basics/worldwide-taxation/.

- Willens, Robert, “IRS Moves to Curtail Tax-Free Repatriation of Foreign Earnings”, Tax Notes, August 20, 2012.

- Martin, Xiumin and Rabier, MaryJane and Zur, Emanuel, Dodging Repatriation Tax: Evidence from the Domestic Mergers and Acquisitions Market (June 1, 2015). Robert H. Smith School Research Paper No. RHS 2556519, Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2556519

- Drucker, Jesse (29 December 2010). "Dodging Repatriation Tax Lets U.S. Companies Bring Home Cash". Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-12-29/dodging-repatriation-tax-lets-u-s-companies-bring-home-cash.

- Harris, Jeremiah, and William O’Brien. "US Worldwide Taxation and Domestic Mergers." (2017). Presented at 2017 Journal of Accounting & Economics Conference.https://accounting.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/HarrisOBrien_CV_JAE.pdf

- Harris, Jeremiah; O'Brien, William (4 March 2021). "Foreign Tax Havens and Domestic Acquisitions" (in en). SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2613016. ISSN 1556-5068. http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2613016.

- Hicks, H., & Sotos, D. J. (2008). The Empire Strikes Back (Again)-Killer Bs, Deadly Ds and Code Sec. 367 As the Death Star Against Repatriation Rebels. Int'l Tax J., 34, 37.

- Solomon, E. (2012). Corporate Inversions: A Symptom of Larger Tax System Problems. Tax Notes, 136(12), 1449-1457.

- Donahoe, Michael P.; McGill, Gary A.; Outslay, Edmund (December 2019). "The Geometry of International Tax Planning After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act". National Tax Journal 72 (4): 647–670. doi:10.17310/ntj.2019.4.01. http://dx.doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2019.4.01.

- 26 U.S. Code § 368 - Definitions relating to corporate reorganizations. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/368

- Loomis, S. C. (2011). The double Irish sandwich: Reforming overseas tax havens. St. Mary's Law Journal, 43, 825.

- Lowder, J. Bryan (14 April 2011). "The Double Irish and the Dutch Sandwich". Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2011/04/tax-day-2011-the-double-irish-and-the-dutch-sandwich-a-field-guide-to-exotic-tax-dodges.html.

- Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. United States Tax Alert: Regulations under section 367(a) relating to outbound “F” reorganizations finalized. 22 September 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Tax/dttl-tax-alert-unitedstates-22-september-2015.pdf

- Ament, Joseph (February 2015). "The Impact of Restoration to U.S. Corporations of Foreign Earnings Through Repatriation/Inversions as an Aid to U.S. Economy and Budget". Proceedings of the American Society of Business and Behavioral Sciences 22 (1): 8–15.

- Linebaugh, Kate; Terlep, Sharon (30 June 2013). "Dell's Cash Overseas Is Needed at Home". The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323300004578559492208492874.