Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Elevated CO2 is known to increase yields in C3 crops like rice and wheat, on the other hand, it does not cause a similar increase in C4 crops like maize and sorghum. Drought is known to reduce crop growth and yield.

- elevated CO2

- drought

- photosynthesis

- transpiration rate

1. Introduction

Agriculture is one of the dominant drivers of change in the Anthropocene era; at present about 11 per cent, which is about 1.5 billion ha of the total land surface area, is used for the production of crops on about 36 per cent of the land that is suitable for agriculture [1]. Agriculture is affected by the changing climate, and paradoxically, is also contributing to it. The changing dynamics in climate are the primary and important determinants of agriculture productivity. The effects of this changing climate on overall productivity in agriculture can be understood when we study the effects of individual components contributing to the changing climate on plants and crops.

There is a continuing need to feed the growing population, and globally, the human population of 7.2 billion in mid-2013 is expected to increase to almost 8.1 billion in 2025, and to further grow to 9.6 billion by 2050 [2]. Food security in terms of food availability is imperative in such a scenario. Changing climate is a reality, and slowly we are learning to adapt to it; we are also in the process of devising mitigation strategies so that we can put the brakes on the changes that in general are harmful. The competition for natural resources like land, water and energy will keep growing at a pace with which it would be difficult for us to manage unless we have sound strategies in place to adapt to the harmful effects of changing climate and further mitigate the effects of changing climate.

The effects of climate change on particular areas, specifically agriculture, are difficult to predict with a great degree of accuracy, although the overall effects are known and understood. Reports indicate that global average temperatures have increased by about 1 °C since the pre-industrial era, and that anthropogenic warming is adding around 0.2 °C to global average temperatures every decade [3]. The global CO2 in the atmosphere reached 407 ppm in 2018 [4]. Given the current rate of generation of CO2, it can be expected that it will exceed 600 ppm by the end of this century [5]. The levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) are changing rapidly; CO2 concentration in the atmosphere can directly affect the growth and development of vegetation in general, and it is indirectly affecting plant growth due to seasonality and variability in rainfall it causes.

Elevated CO2 and drought due to low variability in rainfall are important manifestations of the changing climate. There is a considerable amount of literature that addresses these aspects in terms of effects on plant systems from molecules to ecosystems. Of particular interest is the effect of increased CO2 on plants in relation to drought and water stress. Increases in the source of carbon can have favourable effects on plants in relation to their growth and development, and this can be more pronounced in the presence of optimum-to-high levels of nutrients in the soil and increased water availability. These effects may be of short duration and can vary according to the photosynthetic metabolism of the plants like in C3, C4, CAM and C3-C4 intermediate plants. In addition, there are studies which show that C3 crops show increased growth and yield under eCO2 when grown under both wet and dry growing conditions. C4 crops show increased growth and yield only under dry growing conditions and drought leads to stomatal limitations of C3 and C4 crops and is alleviated by eCO2.

The forecasts for the coming decades have projected varying changes in precipitation that can result from the increasing frequency of droughts and floods [6]. Drought is one of the important abiotic stresses in the present changing climate scenario and the study of the mechanism by which it affects plant metabolism, growth and development is of paramount importance. In the past decade, global losses in crop production due to drought totalled USD 30 billion [7]. The loss in crop production due to drought in the past ten years has been close to about 30 billion and it is estimated that about 5 billion people will be in water-scarce regions of the world by 2050, emphasising the importance of studying all the facets of drought and plant growth. Interestingly there are studies where crops are grown under field conditions, and the positive impact of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations on productivity was found to be significantly stronger under soil water limitation than under potential growth conditions, as reported in [8] for cotton, [9] for wheat, [10] for alfalfa, and also for temperate pasture species [11]. There are also evident interactive effects of elevated CO2 and other environmental conditions that are indicative of changing climate like drought, heat, and other stresses that invariably accompany elevated CO2 conditions in the atmosphere. The importance of understanding this complex relationship is imperative in a high CO2 atmosphere that is envisaged in future, to counter the effects of changing climate. As it is known that one of the consistent effects of increased CO2 in the atmosphere is increased photosynthesis, especially in C3 plants, it will be interesting to know the effect of drought in relation to elevated CO2.

2. Water Relations, Transpiration and Stomatal Conductance

2.1. Stomatal Dynamics

Elevated CO2 concentration is known to mitigate the effects of drought stress, and in a study on Populus spp. and Salix spp. by [12] it was found that when these two species were grown in ambient (350 µmol mol−1) or elevated (700 µmol mol−1) predawn water potential reduced as water stress increased, as against midday water potential which did not show any changes. The changes observed were 0.1 MPa at predawn and 0.2 MPa at midday. Increased elasticity of the cell wall is usually observed when there are altered water relations. These cellular changes allow the tress to maintain higher turgor at lower water potentials and tissue water content. The mitigating effect of higher CO2 was by increasing ψp at the same levels ψw which can result in osmotic adjustment. This mechanism of osmotic adjustment can improve plant metabolism or at least maintain plant metabolism at optimal levels resulting in acclimation to drought. Stomatal dynamics drive the carbon uptake during water deficit stress and when there is accompanying stress like short-term elevated CO2, the role of stomatal limitation in the assimilation of carbon may reduce with a reduction in photorespiration and increase in the partitioning of soluble sugars and increase in water use efficiency.

The eCO2-mediated regulation of stomatal conduction and transpiration rate is mainly by regulating stomatal aperture as a short-duration response [13,14,15] and other long-duration morphological modifications like changes in stomatal density [16,17]. Varied crop-specific responses were also seen [17] in stomal density where eCO2 increased the density of stomata in maize whereas the same decreased in Amarnath. It is interesting to note here the differences in dicot and monocot response of both the C4 crops. The general response observed in both the C4 crops is because under water deficit conditions C4 crops are better performing under elevated CO2 as they have a CO2 concentrating mechanism; this mechanism favours optimum photosynthesis even under lower stomatal conductance, and they can close their stomata and still perform the dark reaction with an optimum amount of CO2. On the other hand, the differences between dicot and monocot C4 plants under elevated CO2 may be due to the higher degree of suberization in the kranz anatomy specifically in the NADP–ME subtypes which are not seen in the dicots specifically in the NAD–ME subtype [17].

Studies on stomatal density have been indecisive in their outcomes as to what exactly is governing the decrease and increase in the density under stress conditions, although a large body of evidence says that it is one of the key morphological traits that regulates transpirational flux resistance in the leaf and conductance of stomata under eCO2. The underlying mechanism is shifting the balance in favour of CO2 uptake by increasing it under water loss conditions. On the other hand, a recent study has also suggested that stomatal density may be equally or more affected by temperature, specifically the large continental-scale geographical variations with an interplay of precipitation [18].

The mechanism of guard cell sensing of CO2, especially in enriched conditions and this sensing playing a role in the turgor dynamics of the cells, has gained much acceptance in recent times; the support for this comes from the fact the CO2 itself is lipophilic and can easily diffuse across membranes and also move through mass flow across aquaporins. The mechanism is explained by the triggering of CO2 of the efflux channels of K+ out which in turn increases the water potential inside the cell, and this results in water moving out and in effect resulting in stomatal closure [19,20].

2.2. The ABA Conundrum

Abscisic acid (ABA) is mainly involved in the regulation of many important physiological processes in the plant at the cellular level. ABA synthesis activates many types of countering mechanisms in plants under stress, among which the main mechanism is the stomatal movement. Opening and closing are regulated in such a way that there is minimum loss of water during water deficit conditions [21,22]. The interplay of ABA and eCO2 has been of interest to researchers as some of the mechanisms by which they regulate stomatal dynamics seems to be the same.

We have seen that eCO2 can mitigate drought-induced stress in plants through osmotic adjustment, changes in turgor pressure and changes in root shoot ratio, and the mechanism here is higher hydraulic conductance induced maintenance of higher relative water content (RWC). This is in addition to optimum water status being maintained by hydraulic conductance. On the other hand, when there is an interaction of eCO2 with drought, we are faced with the question as to what exactly is contributing to the stomatal dynamics. Is it the eCO2-induced changes in the stomata, or is it the drought-induced ABA production that is instrumental, or is it an action of both these agents in tandem?

The mechanism and the effect become complex when we see that both ABA and eCO2 induce stomatal closure: in the case of ABA it is reasoned that closure is to prevent excessive loss of water during stress, and in the case of eCO2 the reason for the induced closure is debated. The complexity further increases when we see that under water stress conditions in eCO2 there can be a combined action of both ABA and eCO2. Further, taking the complexity to the next level is the differential effects of eCO2 seen in C3 and C4 plants where the responses are distinct and conserved within the photosynthetic types [19].

Two Tomato genotypes, one of them being a mutant deficient in ABA, were tested for responses of hydraulic conductance at eCO2 by [23]; they found that a reduction in the transpiration rate and a concomitant increase in the water use efficiency (WUE) was seen in the wild type and not in the mutant, clearly indicating a role of ABA in this response. On the other hand, both in the mutant and the wild type, increased water use and osmotic adjustment was seen, showing us that plant water consumption which also includes water transpired is not entirely controlled by ABA. This also shows that osmotic adjustment as a response to water stress can have several other metabolic players and can occur even in the absence of ABA. It is possible that the protective role of ABA under stress is regulated by a higher concentration of CO2 and is manifested in higher WUE and reduced transpiration rate. It is generally thought that the eCO2-mediated closure of stomata and the opening of stomata are independent of the ABA pathway; on the other hand, some signalling components of the ABA pathway have been implicated to work in tandem, suggesting that some of the components of the regulatory mechanism are shared [24].

The response triggered by both these agents eCO2 and water deficit is interconnected, where ABA is shown to modulate and also regulate the effect of eCO2. Water deficit stress is known to have a stronger effect on stomatal conductance as compared to eCO2 and when in combination with water deficit stress causes a larger decrease in the stomatal conductance which could be an additive effect.

We see here that ROS is a necessary intermediate for ABA-mediated stomatal action in both eCO2 and water deficit, and while ROS is a well-known response under water stress. It is not so in eCO2, so the condition of ROS being a necessary intermediate for stomatal dynamics under sole eCO2 throws up some mechanistic challenges as to how this condition is satisfied, or if there is an alternative mechanism. This question, to an extent, justifies the certain degree of controversy that exists in the convergence of ABA and CO2 signalling [25].

SLAC1 is a membrane protein that is multispanning and is mainly expressed in the guard cells; it has an important role in the regulation of ion homeostasis in the cell and is also involved in S-type anion currents. It is a ubiquitous protein for effecting stomatal closure under various environmental signals like eCO2, water deficit stress, ozone, light regimes and many more. Studies have shown that SLAC1 activity loss due to mutation continues to affect CO2 responsiveness in stomatal closure and does not affect the same way under ABA, suggesting the presence of an ABA independent signalling network under eCO2 conditions to cause stomatal closure. This adds to the intrigue in the signalling response, and possible answers can be found when we can characterize the full complement of guard cell signalling sensors [26,27,28,29,30]. The role of guard cell chloroplasts in regulating CO2 has also been extensively studied; they are not directly involved in the control of stomatal closure as induced by CO2, as it is controlled by the conversion of CO2 to protons by carbonic anhydrases with HCO3 being the primary signalling molecules bringing about changes in the proton concentration, and as a result, controlling the opening and closure of the stomata [31,32,33,34].

We already know that the lower the concentration of CO2, the more the opening of stomata, and as it goes higher the stomata start to close; CO2-induced closure is mediated by Ca2+ and protein phosphorylation, and the specific phosphorylation events are set into motion by signal transduction by Calcium-dependent protein kinases (CPKs) and calcineurin- B-like proteins (CBLs), with the secondary messenger being Ca2+ [35]. Ca2 + also has an ABA modulated and accelerated response, hence Ca2+ transporters and proteins may have a twin function connected to both eCO2 and ABA [36,37,38]. Recent research has shown a role for both eCO2 and ABA in stomatal closure.

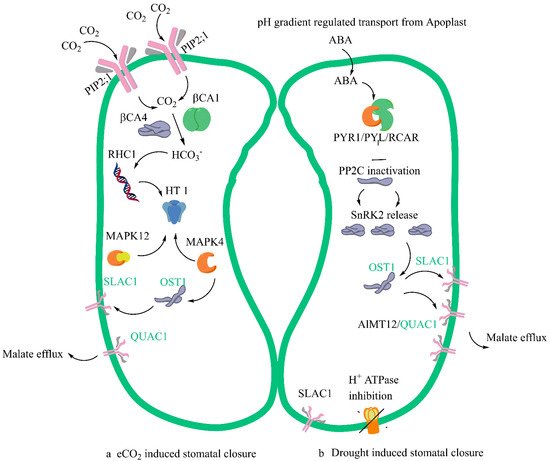

The common pathway or overlap, or sometimes called the convergence point in the mechanism of stomatal closure, involves three different events. The first is the signal perception by SLAC1 of HCO3 where there is an involvement of several protein kinases, and this signalling activates the SLAC1 anion channel. The signalling is downstream of the Open Stomata 1 and Sucrose non-fermenting related Kinase (1OST1/SnRK1) pathway [15,39,40]. The mechanistic differences in the eCO2-mediated stomatal closure and ABA-mediated stomatal closure are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A simplified model of stomatal closure effected by eCO2 (a) and ABA (b) with commonality and convergence in the mechanism shown in green. Several Aquaporins felicitate the entry of CO2 in guard cells. Plasma membrane intrinsic protein (PIP2;1) aquaporin that facilitates water transport across the cell membrane and carbonic anhydrases (b CA4 and b CA1) interact leading to the in-creased formation of Bicarbonate (HCO3−). The multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE)-type transporter RESISTANT TO HIGH CARBON DIOXIDE 1 (RHC1) gene product senses HCO3 signalling. Carbon Dioxide and Bicarbonate together act as signal transduction molecules. Under eCO2 the possible action would be the activation of MPK12 and MPK 4 resulting in the inhibition of expression of protein kinase HIGH LEAF TEMPERATURE1 (HT1). When ABA enters the guard cells, in the ABA-mediated closure PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1 (PYR1)/PYR1-LIKE (PYL)/REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTORS (RCAR) it interacts with Type 2C protein phosphatases (PP2Cs) and inhibits them. The proton translocating ATPase is inhibited in the process by ABA and this prevents proton entry into the guard cells and regulates its pH. There is a subsequent release of Ca2+-independent protein kinases (SnRK2s). SLAC1 ion channel is phosphorylated by the activation of SnRK2 and calcium dependent protein kinases (CPK). The convergence step under both eCO2 and ABA is the activation of Rapid type ion channel aluminium-activated malate transporter 12/quickly activating anion channel 1 (ALMT12/QUAC1) which leads to the turgor dynamics and K+ ion efflux and resultant stomal closure.

2.3. Water Relations

In a study with field experiments and process-based simulations [41], the authors have shown that CO2 enrichment contributes to decreased water stress and also contributed to higher yields of maize under restricted water conditions. They showed from their studies that elevated CO2 decreases transpiration without any effect on soil moisture and at the same time it increases evaporation. Modelling has shown that water stress is reduced to an extent of 37 per cent under elevated CO2, a simulated increase in stomatal resistance being the reason for this.

Some of the effects of water stress in combination with elevated CO2 can be understood when we see the effects observed in Free Air CO2 enrichment (FACE) experiments. In maize elevated CO2 reduces transpiration and this, in turn, contributed to the increase in soil moisture and evaporation. In a simulated study [41] it was seen that transpiration was reduced by 22 per cent in the first year of the experiment. In another study [42] the authors showed that in a FACE experiment transpiration in maize was reduced significantly under 550 ppm CO2 concentration. Daily sap flow and vapour pressure deficit (VPD) of maize were investigated [43], and it was seen that whole-plant transpiration was reduced by 50 per cent in drought as compared to wet in ambient CO2 concentrations, and 37 per cent reduction was observed in elevated CO2 concentration of 550 ppm. Enrichment of CO2 did not affect sap flow under drought and a 20 per cent decrease was seen under wet conditions. Maize under elevated CO2 had a higher transpiration rate which was due to lower sap flow in the preceding period when plant-available soil water was minimum, this shows that reduction in canopy transpiration by elevated CO2 can delay the effects of water stress and can contribute to increased plant biomass production.

Another study [44] on the physiological response of two C3 and C4 mechanisms syndromes, examined Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schumach × Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br) and hydric common reed grass (Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steud); under water stress and elevated CO2 it was seen that there was a general response of increase in photosynthesis, reduced leaf water potential, and increase in transpiration in both the grass species. A contrasting response was seen in the two types of grass to elevated CO2 and water stress; the difference in the species response was due to the stomatal characteristics as evidenced by the changes in transpiration rate and osmotic adjustment. Water status adjustment by modification of xylem anatomy and hyrodolyic properties is a mechanism found in many plants, and its relationship with the observed effect of elevated CO2 to increase plant water potential via reduced stomatal conductance and water loss has been studied [45]. One of the known adaptations to water stress by plants is to maintain high water potential and turgor pressure under water-deficient conditions. The authors saw in their study that water deficit significantly decreased xylem vessel diameter, conduit roundness and stem cross-section area, and it was seen that these impacts of water deficit were relieved at elevated CO2. In another study [46] where the adverse effects of the drought were studied on soyabean under elevated CO2, the authors found that elevated CO2 increased WUE contributing to countering drought, but they did not find any positive effects on osmotic adjustments.

The effects of Elevated CO2 individually and in combination with a water deficit in soyabean were studied [47]. In instantaneous water stress treatment, elevated CO2 reverted the expression of genes related to stress, transport and nutrient deficiency that was induced by water stress; the interaction of drought and elevated CO2 affected the expression of genes with physiological and transcriptomic analysis showing that elevated CO2 can mitigate the negative effects of water stress in soyabean roots.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology11091330

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!