Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Approximately 356 species of turtles inhabit saltwater and freshwater habitats globally, except in Antarctica. Twenty-four species of turtles have been reported in Malaysia, four of which are sea turtles. The state of Terengganu harbored the highest number of turtles, with 17 different reported species.

- taxonomic

- sea turtles

- IUCN Red List

- CITES

1. Introduction

There are approximately 356 turtles living on land on every continent, except for in Antarctica, as well as in salt water and fresh water [1]. The term “turtle” is frequently used to refer to sea turtles, which only rarely leave the sea [2]. Sea turtles belong to the Cheloniidae families, except for the Leatherback turtle, which is the only genus in the Family Dermochelyidae and has a leathery carapace [3]. The seven species of sea turtles are Green turtle (Chelonia mydas), Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), Leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), Flatback turtle (Natator depressa), Olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea), and Kemp’s ridley turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) [4]. Malaysia is home to four sea turtle species: the Leatherback turtle, the Green turtle, the Olive ridley turtle, and the Hawksbill turtle [5]. With nearly 40% of its total body mass made up of bone, the turtle is possibly the most organized form of animal armor ever to appear [6]. As a result, this great armor is most likely why turtles appeared on the scene over 200 million years ago and miraculously survived the extinction of the dinosaurs and other devastating events [6].

In Testudines’ order, turtles are any reptile with a hard shell around its body, including tortoises [7]. They have anatomical characteristics that set them apart from other turtles. In the Chelonia order, a turtle, a tortoise, and a terrapin are all names for hard-shelled egg-laying reptiles [8]. However, the specific expression used for a particular turtle can vary depending on its natural surroundings. For example, the term “turtle” usually refers to turtles that have spent their entire lives in or near water [9]. The term “tortoise” is commonly used to refer to turtles that spend most of their time ashore, eating bushes, grass, and fruit [10]. Unlike other turtle family members, tortoises do not have webbed feet because they do not spend much time in the water [11]. Terrapins are turtles that invest energy in fresh and brackish water [12]. “Terrapin” is derived from an Algonquian Indian word that means “a small turtle” [13]. Malaysia is home to 20 different kinds of turtles. Two of them, Pelodiscus sinensis and Trachemys scripta, were brought there from other places [14]. In total, Malaysia has 24 different species of turtles [15].

2. Turtle Types in Malaysia

The “hard-shelled” Cheloniidae advanced around 60 million years ago, and the “delicate-shelled” Dermochelyidae developed approximately 90 million years ago [28,29]. The Cheloniidae contain six surviving species in five genera: the Flatback turtle (Natator depressus), the Green turtle (Chelonia mydas), the Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), the Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), the Kemp’s ridley turtle (Lepidochelys kempii), and the Olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). The Leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) is the only extant species in the Dermochelyidae family [30].

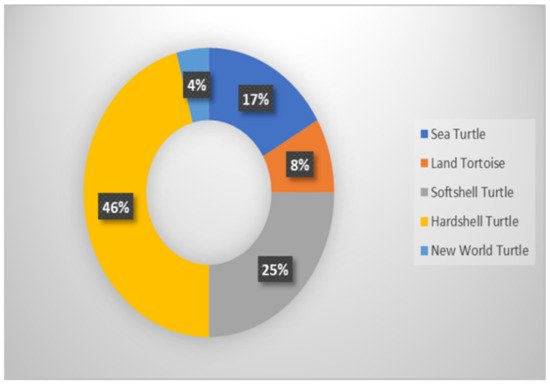

There are seven sea turtle species (Cheloniidae and Dermochelyidae) worldwide, with five nesting in Southeast Asia. Figure 1 shows that 17% of the studied sea turtles can be found locally. The other two species are the Kemp’s ridley turtle, which only lives in the Western Atlantic Ocean, and the Flatback turtle, which only lives in Australia (though its feeding grounds extend into Eastern Indonesia) [31].

Figure 1. The diversity of turtles in Malaysia.

Testudinidae (Land Tortoises): 60 land tortoise species are recognized worldwide, accounting for 8% of the 24 turtle species in Malaysia (Figure 1). Most of them live in semi-arid, dry open habitats, including grasslands and deserts [32]. Only five Southeast Asian species have adapted to different environments, including humid, forested habitats, and cooler temperatures in a lower montane forest [31,33]. Supplementary Table S1 shows some examples.

Asian hard-shell turtles (Geoemydidae) have the most turtle family species, with approximately 40 species of 14 genera found in Southeast Asia and 70 species found worldwide. Malaysia has the most of this turtle type (46%) (Figure 1). DNA sequencing has recently revealed hidden diversity in this group; for example, the Cyclemys leaf turtles are now classified as six distinct species [31]. Supplementary Table S1 shows some examples.

The big-headed turtle (Platysternon megacephalum) is mainly the only individual from this family, Platysternidae; it is remembered for the superfamily Testudinoidea, which likewise incorporates the Testudinidae (land turtles), Geoemydidae (Asian hard-shelled turtles), and Emydidae (new world reptiles). This turtle has a large head that it cannot retract into its shell [34].

Softshell turtles (Trionychidae) have 30 species worldwide [35], with 15 species in Southeast Asia and six found in Malaysia (Supplementary Table S1). They also have a flexible, rugged carapace [36], and Southeast Asia is home to approximately half of the world’s softshell turtles [31,33].

The snake-necked turtles of the Chelodina family are an ancient group of expert fish-eaters whose long necks must be turned sideways to reach beneath the carapace [37]. There are 16 species in the world under this family [31,38].

The pig-nosed turtle (Carettochelys insculpta) is the only species in the Carettochelyidae family [39]. It is found in just three nations—Indonesia, Papua, New Guinea, and Australia [40]. These species are kept as pets in Malaysia. Their flippers resemble those of sea turtles, and their carapace is rough, but their most unique feature is their pig-like nose [31,41].

Turtles from the Emydidae family originated in the Americas and are widely available in the world as the most popular pet [42]. For instance, consider the Red-Eared Slider [31].

The turtles in the family Emydidae belong to the order Testudines and the suborder Cryptodira. There are about 52 species in this family, which is divided into 12 genera: Actinemys, Chrysemys, Clemmys, Deirochelys, Emydoidea, Emys, Glyptemys, Graptemys, Malaclemys, Pseudemys, Terrapene, and Trachemys [43]. Except for Trachemys, which is found in South America and the West Indies, and Emys, which inhabits Southern Europe, Northern Africa, and Western Asia, all of these species are restricted to North America [44]. The relationships between the 12 genera and the species that make up the family are yet unknown [45].

3. Conservation Status

3.1. The Status of the IUCN Red List

The IUCN Red List categorizes species into nine groups (Table 2), which Reference [100] defined based on population size, rate of decline, geographic distribution area, fragmentation distribution, and population degree. The importance of applying any measures without extensive information, including suspicion and potential future threats, is emphasized “so long as these can reasonably be supported” [19]. The “Threatened” category includes “Critically Endangered”, “Endangered”, and “Vulnerable” [21] on its Red List.

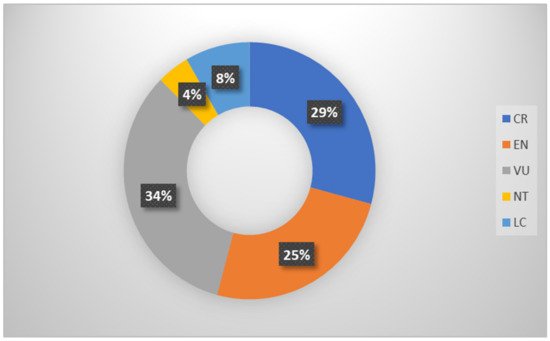

Table 3 shows that Malaysia has 24 turtle species, four of which are sea turtles, and the other 20 are freshwater turtles (two of which are introduced species) [14,101]. According to the IUCN Red List, a sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) and six freshwater turtle populations (Manouria emys, Batagur affinis, Orlitia borneensis, Batagur borneoensis, Indotestudo elongata, and Chitra chitra) are critically endangered in Malaysia (Figure 2). In contrast, a sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) and five freshwater turtles (Heosemys annandalii, Cuora amboinensis, Heosemys spinosa, Chitra indica, and Pelochelys cantorii) were endangered in Malaysia. Two sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea and Lepidochelys olivacea) and six freshwater turtles were vulnerable (Malayemys macrocephala, Notochelys platynotan, Siebenrockiella crassicollis, Amyda cartilaginea, Manouria iimpressa, and Pelodiscus sinensis). However, two sea turtles were reported by Reference [102] in The ASEAN Post; a source from the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) Malaysia shows that the Leatherback turtle is critically endangered, and the Olive Ridley turtle is endangered in the Malaysian ocean. Moreover, one species, Cyclemys dentata, is near threatened, and two species, Dogania subplana and Trachemys scoundaripta, are less concerned.

All the turtle species are distributed all over Malaysia. However, Terengganu is home to 17 species, including four species of sea turtles (Chelonia mydas, Dermochelys coriacea, Lepidochelys olivacea, and Eretmochelys imbricata) and 13 species of freshwater turtles (Trachemys scripta, Batagur affinis, Batagur borneonsis, Coura amboinensis, Siebenrockiella crassicollis, Manouria emys, Amyda cartilaginea, Dogania subplana, and Pelochelys cantorii) [14]. In addition, referring to Figure 3, the IUCN Red List analysis shows that 29 percent of Malaysia’s turtle species are critically endangered and 25 percent are endangered.

| Classification | Describtion |

|---|---|

| Not evaluated (NE) | Not yet assessed by the IUCN, they indicate species that have not been reviewed enough to be assigned to a category. |

| Data deficiency (DD) | Offering insufficient information for a proper assessment of conservation status to be made. |

| Least concern (LC) | It is unlikely to become extinct soon. |

| Near threatened (NT) | Close to being at an increased risk of extinction soon. |

| Vulnerable (VU) | It is considered at an increased risk of unnatural (human-caused) extinction without further human intervention. |

| Endangered (EN) | A very high risk of extinction in the wild. |

| Critically endangered (CR) | Points in a particular and extremely critical state. |

| Extinct in the wild (EW) | Point only lives on in zoos, farms, and places outside of its native range, as surveys have shown. |

| Extinct (EX) | Beyond a reasonable doubt, the species is no longer extant. |

| Common Name | Scientific Name | GenBank Accession |

IUCN Red List Status | CITES Appendix |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian Narrow Headed Softshell Turtle | Chitra chitra | HQ329770 | CR | I | [105] |

| Hawksbill Turtle | Eretmochelys imbricata | GQ152887 | CR | I | [71] |

| Southern River Terrapin | Batagur affinis | MN069310 | CR | I | [106] |

| Asian Giant Tortoise | Manouria emys | KP268838 | CR | II | [107] |

| Elongated Tortoise | Indotestudo elongata | KP268857 | CR | II | [108] |

| Malaysian Giant Turtle | Orlitia borneensis | HQ329693 | CR | II | [105] |

| Painted Terrapin | Batagur borneoensis | HQ329672 | CR | II | [105] |

| Green Turtle | Chelonia mydas | MN124278 | EN | I | [109] |

| Asian Giant Softshell Turtle | Pelochelys cantorii | HQ329785 | EN | II | [105] |

| Indian Narrow-headed Softshell Turtle | Chitra indica | HQ329771 | EN | II | [105] |

| Malaysian Box Turtle | Cuora amboinensis | JN860217 | EN | II | [108] |

| Spiny Turtle | Heosemys spinosa | HQ329684 | EN | II | [105] |

| Yellow-headed Temple Turtle | Heosemys annandalii | HQ329681 | EN | II | [105] |

| Leatherback Turtle | Dermochelys coriacea | KU883273 | VU | I | [110] |

| Olive Ridley Turtle | Lepidochelys olivacea | KF894766 | VU | I | [111] |

| Asiatic Softshell Turtle | Amyda cartilaginea | HQ329768 | VU | II | [105] |

| Black Marsh Turtle | Siebenrockiella crassicollis | HQ329704 | VU | II | [105] |

| Impressed Tortoise | Manouria impressa | GQ867670 | VU | II | [112] |

| Malayan Flat-shelled Turtle | Notochelys platynota | HQ329692 | VU | II | [105] |

| Malayan Snail-eating Turtle | Malayemys macrocephala | HQ329686 | VU | II | [105] |

| Chinese Softshell Turtle | Pelodiscus sinensis | JQ844545 | VU | None | [113] |

| Asian Leaf Turtle | Cyclemys dentata | HQ329676 | NT | II | [105] |

| Malayan Softshell Turtle | Dogania subplana | NC_002780 | LC | II | [114] |

| Yellow-bellied Slider Turtle | Trachemys scripta | JF700194 | LC | None | [115] |

Figure 3. Chart of IUCN Red List status on turtles.

3.2. The CITES Appendices

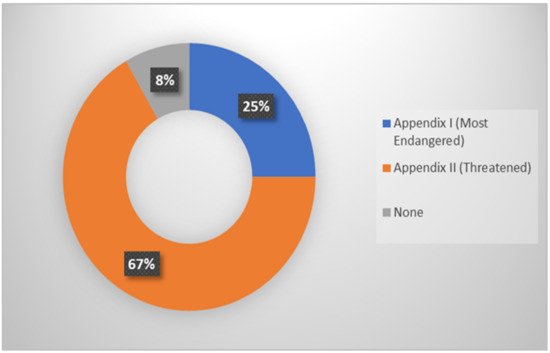

The Convention’s Appendices I, II, and III are lists of species with different levels of protection from over-exploitation [123]. Appendix I lists the most endangered plants and animals on the CITES list. They are almost extinct, but CITES allows international trade in specimens of these species as long as the import is not for commercial use (i.e., a scientific research study) [124].

In Appendix II, there is a list of species that are not threatened with extinction right now, but if the trade is not controlled, there is a high chance that they will be in the future. It also includes supposed “similar species”, such as species whose standards in exchange resemble species recorded for conservation purposes. Trade-in specimens of Appendix-II species may be authorized by issuing an export permit or re-export permit certificate. No import permit is necessary for these species under CITES (although a permit is needed in some countries with stricter measures than CITES requires) [125].

Appendix III contains a list of species added at the request of a party that already regulates international trade in the species. Specimens of the species in this appendix can be traded around the world only if the proper permits or certificates are shown [123].

An analysis of Figure 4 reveals that CITES has classified Malaysian turtles as 67 percent threatened, including Manouria emys, Orlitia borneensis, Batagur borneoensis, Indotestudo elongate, Heosemys annandalii, Cuora amboinensis, Heosemys spinosa, Chitra indica, Pelochelys cantorii, Malayemys macrocephala, Notochelys platynotan, Siebenrockiella crassicollis, Amyda cartilaginea, Manouria impressa, Cyclemys dentata, and Dogania subplana. About 25% (Batagur affinis, Chitra chitra, Eretmochelys imbricata, Chelonia mydas, Dermochelys coriacea, and Lepidochelys olivacea) are the most endangered species.

Figure 4. Chart of CITES’s appendices on turtles.

4. Threat Factors

The [21] population trends for all VU, EN, and CR turtle populations are decreasing. In conclusion, many factors contribute to threats. This entry compiles and documents the work of other Malaysian researchers and decision-makers for future reference (Figure 5). The primary causes of concern are egg consumption and trade [4,126]. The main threats to turtles are illegal and unregulated turtle poaching by Hainan (China) vessels and Vietnam [1]. Turtles are hunted for food, medicine, and ornaments [127]. In Malaysia, religious beliefs have reduced the killing of adult turtles for food [128]. On the other hand, building dams, taking turtle eggs, removing riparian vegetation, sand mining, and drowning in fishing nets are some of the turtle’s most significant problems [129,130,131,132,133].

Figure 5. These threat factors were compiled from IUCN data, the DOF Report, DWNP Report, TRAFFIC South-east Asia Report, species-recovery plans, federal-agency re-sponses, and miscellaneous publica-tions on species’ life history. A complete list of documents used to assign biological attributes to endangered species is available from the authors.

According to References [134,135], the most critically endangered turtle species may become the most sought after due to their scarcity, which makes them especially valuable in the pet trade, hunting, and habitat degradation. Reference [136] reports that they are eaten, collected, butchered, and traded in large numbers; they are used for pets, food, and traditional medicine—eggs, juveniles, adults, and body parts are all exploited indiscriminately, with no regard for sustainability [137]. Their habitats are being destroyed, developed, fragmented, and polluted at an alarming rate [138,139]. Species all over the world are threatened or vulnerable, with many critically endangered. Others are on the verge of extinction, and a few have already perished [140]. Humans are threatening the extinction of countless eons and turtles [141].

Aside from overt and highly impactful conservation threats such as overexploitation and habitat destruction, the global turtle fauna is also increasingly facing another insidious threat: genetic pollution caused by human-facilitated hybridization and introgression from introduced and invasive species [142,143,144,145,146]. Although it is not entirely new, the current scale is unprecedented. Some taxa have already been impacted in the past. This is most likely true for Pelodiscus Asian softshell turtles. These turtles have been farmed and traded for hundreds of years. As a result, different species and local genetic lineages have been moved, leading to other taxa and lineages in captivity and the wild [147,148].

Similarly, the historical introduction of Mauremys reevesii to Japan resulted in massive hybridization with the native [149]. Another historical case of human-mediated admixture of genetic lineages is known from European pond turtles (Emys orbicularis). The non-native populations on the Balearic Islands, which were most likely introduced during Roman times [150], are of admixed origin [151]. Another population with genetic signatures of an old or ancient introduction of Emys orbicularis hellenica was discovered near Rome [151,152] within the range of another subspecies (Emys orbicularis galloitalica). However, unlike in the past, when only a few turtle species were affected, genetic pollution has become a big problem in protecting wildlife in recent years. This is because of the huge pet and food trade and increased human mobility.

Today, genetic pollution is also caused by well-meaning augmentation of endangered local turtle populations with genetically mismatched individuals (typically, but not exclusively, from non-coordinated actions by turtle enthusiasts), the release of surplus or abandoned genetically divergent pet turtles, and also by large-scale releases of confiscated turtle shipments, especially in Southeast Asia. Some endangered Emys orbicularis populations are on the northern edge of their range [153,154], and there is genetic evidence for restocking with multiple subspecies; in southern France [152,155], there is evidence of restocking with non-native Emys orbicularis hellenica rather than native Emys orbicularis. Examples of genetic pollution caused by abandoned pet turtles include Chrysemys picta bellii from British Columbia, introgressed by non-native subspecies [49], and Antillean (Trachemys), introgressed by Red-Eared Sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) [156]. As previously stated, some cases involving European pond turtles are related to genetic contamination caused by abandoned pet turtles. In Taiwan, hybridization between Mauremys reevesii and Mauremys sinensis has been observed in the wild in released trade animals [157]. According to Reference [158], preserving well-defined genetic lineages, subspecies, and species that are mostly pure and not hybridized is critical. Therefore, in Malaysia, the two introduced species potentially cause genetic pollution.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ani12172184

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!