Antifungals (also referred to as antimycotics) are the type of antibiotics used to treat fungal infections. In contrast to bacteria, fungi are eukaryotic organisms; thus fungal cells are very similar to our own cells. Because of this there is a limited number of selective targets and the current arsenal of antifungal drugs is very limited, which contributes to high mortality rates. In addition, development of resistance against current antifungals poses additional challenges. Clearly, new antifungal agents are urgently needed.

- Antifungals

- antimycotics

- fungal infections

- mycoses

- azoles

- polyenes

- echinocandins

1. Introduction

It has been estimated that there are up to 5 million fungal species populating the earth today [1], of which approximately 100,000 species have been identified. Interestingly, to date, only about 300 fungal species have been described to cause disease in humans. Fungi that infect humans must satisfy a set of four particular characteristics: they must have the ability to grow at or above 37 °C; they must have the ability to reach the tissues associated with their pathogenesis; they must be able to digest and absorb elements of human tissues for their own nutrition; and lastly they must withstand the human immune system [2]. Those fulfilling these criteria are able to cause a variety of infections that range from skin and mucosal infections to life-threatening invasive infections, with less than 30 species causing over 99% of infections [3]. Although a few fungal species are fully capable of causing infections in healthy immunocompetent individuals, the majority of them are opportunistic pathogens, requiring a susceptible host [4]. Thus, besides the recent HIV epidemic, the major contributing factor for the increase in fungal infections has been the fact that advances in modern medicine and the successful treatment of serious underlying diseases have created an ever-expanding population of immunosuppressed and medically compromised patients who are inherently susceptible to these devastating infections [4].

2. Current Antifungal Drugs

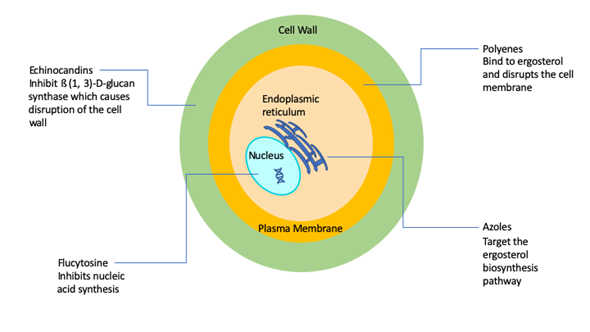

A major factor contributing to the high levels of morbidity and mortality of fungal infections is the limited number of antifungal drugs [5]. Fungi, like humans, are eukaryotic organisms and there is a paucity of selective targets that can be exploited for antifungal drug development. As a consequence, and in stark contrast with antibacterials, the current antifungal armamentarium is still very limited [5][6]. The 1990s can be considered the “golden era” of antifungal drug development with multiple big pharmaceutical companies actively engaged in the discovery and development of novel antifungals. However, antifungal drug development has largely become stagnant since then, and it has been now two decades since the newest class of antifungal agents (the echinocandins) reached the market. Overall, there are currently four classes of FDA-approved antifungal agents clinically used in the treatment of invasive fungal infections, namely the polyenes, flucytosine, the azoles, and the echinocandins [7] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simplified schematic diagram depicting the current antifungals and their modes of action.

The polyenes were the first broad-spectrum antifungals available for use in humans with their discovery in the 1940s and 1950s [7], with Amphotericin B representing the first ever FDA-approved antifungal for the treatment of invasive fungal infections [7], and for many years remained the gold standard for the therapy of mycoses. The amphipathic Amphotericin B molecule binds to ergosterol and also acts as a “sponge” that extracts sterols from the cell membranes of fungi [7][8][9][10], leading to a weakened membrane and leakage of cytosolic contents, ultimately leading to cell death. Therefore, polyenes are considered to be fungicidal and display a broad spectrum of activity against most fungal organisms. The major drawback of amphotericin B has always been its toxicity, particularly nephrotoxicity that can lead to kidney failure. Thus, a number of lipid formulations of amphotericin B, including liposomal amphotericin B (LAmB), amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC), and amphotericin B colloidal dispersion (ABCD) have been developed, which generally show decreased toxicity and improved pharmacokinetics, which depend to a large extent on the composition and particle size of the nanoformulations [11]. For example, LAmB is composed of small unilamellar particles (true liposomes), resulting in high serum and CNS concentrations, whereas ABLC and ABCD typically achieve much higher levels in organs of the reticuloendothelial system [11]. A major drawback of these formulations is that they are significantly more expensive than conventional amphotericin B. In general, resistance to amphotericin B is rare, although some fungal species display intrinsic resistance to polyenes [12][13].

The antifungal 5-fluorocytosine was first synthesized in 1957 as a potential anti-tumor agent, and it was approved for use in humans as an antifungal in 1968 [14][15]. Flucytosine is a pyrimidine, known to inhibit DNA and RNA synthesis in fungi because of its ability to be metabolized to 5-flourouracil that is then incorporated into RNA [16][19]. A major problem with flucytosine is the extremely common occurrence of the development of resistance, and, because of this, it is never used in monotherapy, but rather in combination with other antifungals [17]. In addition, hepatotoxicity and hematological toxicity are common adverse effects at target concentrations [14]. Its clinical use is mostly restricted to the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis [14][18].

The first azole was discovered in 1944, but azoles were not approved for use in humans until the late 1950s/early 1960s [7]. Azoles inhibit 14-α-sterol demethylase, a cytochrome P-450 enzyme involved in the synthesis of ergosterol [19], which results in the accumulation of toxic sterol intermediaries and loss of membrane integrity. Most azoles are fungistatic and have a relatively broad spectrum of activity against yeasts and filamentous fungi [18][20]. The introduction of triazoles in the clinics during the 1980s and 1990s revolutionized the treatment of fungal infections [21][22]. The most common azole used in systemic fungal infections, particularly those caused by yeasts (i.e., Candida, Cryptococcus), is fluconazole, which was released in 1990. However, some fungal species, including Aspergillus and other emerging moulds, display intrinsic (or primary) resistance to fluconazole, and other derivatives were developed that display activity against Aspergillus (i.e., itraconazole, voriconazole) and those with an expanded spectrum of activity that includes the mucorales (i.e., posaconazole and most recently isavuconazole). Due to their fungistatic nature, the development of resistance is a common occurrence during treatment with azoles, mostly through mutations in the target gene ERG11, but also because of the overexpression of efflux pumps that transport the azole molecules outside the cell [12]. In spite of resistance, azoles are still some of the most commonly used antifungal drugs for the treatment of a variety of fungal infections.

The echinocandins are the most recent class of antifungals that have been approved by the FDA [18][23]. They were first discovered in the 1970s but did not enter the market until the early 2000s [24]. They target 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase, an enzyme responsible for the production of 1,3-β-D-glucan, a polysaccharide which constitutes the main structural component of most fungal cell walls. Caspofungin was the first echinocandin to be approved for use in humans in 2001 [25][26][27]. Two other echinocandins were subsequently produced and approved: micafungin in 2005 and anidulafungin in 2006 [26][27][28]. Because mammalian cells do not have a cell wall, their target allows for significantly less toxicity and drug–drug interactions as compared to other antifungals [29][30]. These drugs were originally approved for treatment of aspergillosis infections that were refractory to treatment with other antifungals [27][31][32], but they have since been approved for the treatment of candidiasis for which they are now considered the agents of choice, as well as for other fungal infections [24]. Although resistance has been relatively rare, most recently, as a consequence of increased drug exposure, there has been an increase in development of resistance mostly in non-albicans Candida spp. [26]. The main mechanism of resistance against echinocandins is mutations in the FKS1 and FKS2 encoding the target enzyme [12][33][34]. Echinocandins are considered fungicidal and effective against a majority of Candida spp. [27], but fungistatic against Aspergillus spp. [35]. However, the spectrum of action of echinocandins does not include Cryptococcus and some of the emerging pathogens [29][35].

Table 1. The four main classes of clinically-used antifungal agents for the treatment of invasive fungal infections.

|

Antifungal Class |

Mechanism of Action |

Biological Effect |

Spectrum of Action |

|

Polyenes |

Target ergosterol and extract sterols from fungal cell membranes |

Fungicidal |

Broad spectrum antifungal in treatment of invasive fungal infections; resistance is rare |

|

Flucytosine |

Inhibits DNA and RNA synthesis |

Fungicidal against Cryptococcus spp. |

Almost exclusively used for cryptococcal meningitis, but resistance is extremely common so never used in monotherapy |

|

Azoles |

Inhibit 14-⍺-lanosterol demethylase thereby inhibiting ergosterol synthesis |

Mostly fungistatic |

As a class they display broad spectrum against yeasts and filamentous fungi, although some species display intrinsic resistance to commonly used derivatives; secondary resistance can often develop during treatment |

|

Echinocandins |

Target 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase, thus preventing production of cell wall 1,3-β-D-glucan |

Fungicidal against Candida spp., but fungistatic against Aspergillus spp. |

First line of defense for candidiasis and used in aspergillosis when refractory to other treatments; resistance is emerging |

3. Future Targets and Alternative Approaches

In the case of current clinically used antifungal agents, new formulations and delivery systems can, in principle, allow for the development of targeted therapies, which should lead to enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity, resulting in overall improved patient outcomes. The same is true for the application of antifungal pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) principles, where better in vitro and in vivo PK/PD models, more accurate clinical antifungal PK/PD predictions, and therapeutic monitoring may lead to optimized antifungal dosing and increase the probability of a successful outcome for patients with fungal infections. Readers are referred to excellent reviews on these topics [36][37].

Of course, the basic research currently being conducted mostly in academic settings may provide important information on potential fungal-specific pathways and novel antifungal targets as well as pave the way in the near future for the development of new antifungal drugs with new molecular structures and mechanisms of action. Perhaps among the most promising targets to date are the calcineurin and RAS pathways, sphingolipid biosynthesis, as well as the trehalose biosynthetic pathway. This topic has been reviewed recently in an excellent and rather insightful publication [3].

Moreover, research on the mechanisms of fungal pathogenesis over the past two–three decades, and in particular during the post-genomic era, may lead to the development of novel anti-virulence agents, which exert their activity by disarming the fungal cells of their virulence properties as opposed to inhibiting their growth, and may serve as the basis for alternative approaches for the treatment of fungal infections [38][39]. This is a particularly attractive alternative to combat infections caused by opportunistic pathogenic fungi. One of the main advantages of anti-virulence approaches is that they automatically expand the number of potential antifungal targets. Moreover, because of lower selective pressure, anti-virulence approaches have lower propensity to elicit antifungal drug resistance. C. albicans has been the organism for which more work on this topic has been performed to date, with filamentation and biofilm formation, two of the most important virulence factors inextricably linked to the pathogenesis of candidiasis, having been identified as high-value targets for the development of such novel anti-virulence strategies [40][41].

The last decade has also witnessed an increased interest in repurposing as a potential accelerated path towards antifungal drug development. In contrast to the arduous, long and very expensive process of de novo drug development, repurposing (also referred to as repositioning) involves the investigation of novel therapeutic indications for existing drugs. Repurposing allows for the identification of drugs with known pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety levels in humans, which, in turn, makes this approach less costly, less time-consuming, and more likely to succeed than traditional de novo discovery. As such, repurposing efforts can lead to the quick deployment of novel antifungal drugs and significantly shorten the transition from bench to bedside. This could be particularly important in case of multi-drug-resistant and emerging pathogens, as exemplified by the rapid spread of C. auris infections in the last few years. Many examples of research aimed at repurposing existing drugs as antifungals can be found in the literature [42][43][44][45][46][47]. Most recently, these efforts have taken advantage of the availability of repurposing libraries, a collection of hundreds of existing drugs, that can be conveniently screened for the identification of drugs with novel antifungal activity [48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56].

Finally, we would like to highlight the use of nanotechnology, using nanoscale materials, as an alternative strategy for antifungal drug development, which has been gaining traction over the last few years [57][58]. These so called “nanomaterials” or “nanoantibiotics” can be described as single structures, the size of which is less than 100 nm in at least one of their three dimensions. The increasing interest in nanomaterials is due to their novel or improved physicochemical properties, such as endurance, chemical reactivity, biocompatibility, conductivity, and reduced toxicity. Although a variety of nanomaterials have been evaluated, the majority of research on this topic has used metal nanoparticles, synthesized by different methods, and evaluated their direct antifungal activity. Of these, silver nanoparticles have received the most attention, as the antimicrobial properties of silver has been known for centuries. The increased antifungal activity is generally associated with the smaller size of the nanoparticles, with shape and surface area also playing a major role. Importantly, nanoparticles have been described to display potent activity against drug-resistant fungal biofilms [59][60].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antibiotics9080445

References

- O’Brien, H.E.; Parrent, J.L.; Jackson, J.A.; Moncalvo, J.M.; Vilgalys, R. Fungal community analysis by large-scale sequencing of environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5544–5550, doi:10.1128/AEM.71.9.5544-5550.2005.

- Kohler, J.R.; Hube, B.; Puccia, R.; Casadevall, A.; Perfect, J.R. Fungi that Infect Humans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0014-2016.

- Perfect, J.R. The antifungal pipeline: A reality check. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 603–616, doi:10.1038/nrd.2017.46.

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T.C. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 165rv113, doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404.

- Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Casadevall, A.; Galgiani, J.N.; Odds, F.C.; Rex, J.H. An insight into the antifungal pipeline: Selected new molecules and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 719–727, doi:10.1038/nrd3074.

- Pierce, C.G.; Srinivasan, A.; Uppuluri, P.; Ramasubramanian, A.K.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Antifungal therapy with an emphasis on biofilms. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013, 13, 726–730, doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.08.008.

- Odds, F.C.; Brown, A.J.; Gow, N.A. Antifungal agents: Mechanisms of action. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 272–279, doi:10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00117-3.

- Te Welscher, Y.M.; van Leeuwen, M.R.; de Kruijff, B.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Breukink, E. Polyene antibiotic that inhibits membrane transport proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11156–11159, doi:10.1073/pnas.1203375109.

- Anderson, T.M.; Clay, M.C.; Cioffi, A.G.; Diaz, K.A.; Hisao, G.S.; Tuttle, M.D.; Nieuwkoop, A.J.; Comellas, G.; Maryum, N.; Wang, S.; et al. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 400–406, doi:10.1038/nchembio.1496.

- Gray, K.C.; Palacios, D.S.; Dailey, I.; Endo, M.M.; Uno, B.E.; Wilcock, B.C.; Burke, M.D. Amphotericin primarily kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2234–2239, doi:10.1073/pnas.1117280109.

- Janknegt, R.; de Marie, S.; Bakker-Woudenberg, I.A.; Crommelin, D.J. Liposomal and lipid formulations of amphotericin B. Clinical pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1992, 23, 279–291, doi:10.2165/00003088-199223040-00004.

- Cowen, L.E.; Sanglard, D.; Howard, S.J.; Rogers, P.D.; Perlin, D.S. Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 5, a019752, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019752.

- Parente-Rocha, J.A.; Bailao, A.M.; Amaral, A.C.; Taborda, C.P.; Paccez, J.D.; Borges, C.L.; Pereira, M. Antifungal Resistance, Metabolic Routes as Drug Targets, and New Antifungal Agents: An Overview about Endemic Dimorphic Fungi. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, doi:10.1155/2017/9870679.

- Vermes, A.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Dankert, J. Flucytosine: A review of its pharmacology, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and drug interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 171–179, doi:10.1093/jac/46.2.171.

- Ashe, W.D., Jr.; Van Reken, D.E. 5-fluorocytosine: A brief review. Clin. Pediatr. 1977, 16, 364–366, doi:10.1177/000992287701600412.

- Larsen, R.A. Flucytosine. In Essentials of Clinical Mycology; Kauffman, C.A., Pappas, P.G., Sobel, J.D., Dismukes, W.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2011; pp. 57–60, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-6640-7_4.

- Viviani, M.A. Flucytosine—What is its future? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1995, 35, 241–244, doi:10.1093/jac/35.2.241.

- Chang, Y.L.; Yu, S.J.; Heitman, J.; Wellington, M.; Chen, Y.L. New facets of antifungal therapy. Virulence 2017, 8, 222–236, doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1257457.

- Whaley, S.G.; Berkow, E.L.; Rybak, J.M.; Nishimoto, A.T.; Barker, K.S.; Rogers, P.D. Azole Antifungal Resistance in Candida albicans and Emerging Non-albicans Candida Species. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2173, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.02173.

- Pianalto, K.M.; Alspaugh, J.A. New Horizons in Antifungal Therapy. J. Fungi 2016, 2, doi:10.3390/jof2040026.

- Martinez-Matias, N.; Rodriguez-Medina, J.R. Fundamental Concepts of Azole Compounds and Triazole Antifungals: A Beginner’s Review. P. R. Health Sci. J. 2018, 37, 135–142.

- Peyton, L.R.; Gallagher, S.; Hashemzadeh, M. Triazole antifungals: A review. Drugs Today 2015, 51, 705–718, doi:10.1358/dot.2015.51.12.2421058.

- Cappelletty, D.; Eiselstein-McKitrick, K. The echinocandins. Pharmacotherapy 2007, 27, 369–388, doi:10.1592/phco.27.3.369.

- Emri, T.; Majoros, L.; Toth, V.; Pocsi, I. Echinocandins: Production and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 3267–3284, doi:10.1007/s00253-013-4761-9.

- Johnson, M.D.; Perfect, J.R. Caspofungin: First approved agent in a new class of antifungals. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2003, 4, 807–823, doi:10.1517/14656566.4.5.807.

- Chen, S.C.; Slavin, M.A.; Sorrell, T.C. Echinocandin antifungal drugs in fungal infections: A comparison. Drugs 2011, 71, 11–41, doi:10.2165/11585270-000000000-00000.

- Sucher, A.J.; Chahine, E.B.; Balcer, H.E. Echinocandins: The newest class of antifungals. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009, 43, 1647–1657, doi:10.1345/aph.1M237.

- Patil, A.; Majumdar, S. Echinocandins in antifungal pharmacotherapy. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 1635–1660, doi:10.1111/jphp.12780.

- Denning, D.W. Echinocandins: A new class of antifungal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 49, 889–891, doi:10.1093/jac/dkf045.

- Shoham, S., Groll, A.H., Petraitis, V.; Welsh, T.J. Systemic Antifungal Agents. In Infectious Diseases, 4th ed.; Elsevier ScienceDirect: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 1333–1344.

- Patterson, T.F.; Thompson, G.R., 3rd; Denning, D.W.; Fishman, J.A.; Hadley, S.; Herbrecht, R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; Morrison, V.A.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e1–e60, doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326.

- Aigner, M.; Lass-Florl, C. Treatment of drug-resistant Aspergillus infection. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015, 16, 2267–2270, doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1083976.

- Perlin, D.S. Current perspectives on echinocandin class drugs. Future Microbiol. 2011, 6, 441–457, doi:10.2217/fmb.11.19.

- Walker, L.A.; Gow, N.A.; Munro, C.A. Fungal echinocandin resistance. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2010, 47, 117–126, doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2009.09.003.

- Aguilar-Zapata, D.; Petraitiene, R.; Petraitis, V. Echinocandins: The Expanding Antifungal Armamentarium. Clin. Infect. Dis 2015, 61 (Suppl. S6), S604–S611, doi:10.1093/cid/civ814.

- Lepak, A.J.; Andes, D.R. Antifungal pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 5, a019653, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019653.

- McCreary, E.K.; Bayless, M.; Van, A.P.; Lepak, A.J.; Wiebe, D.A.; Schulz, L.T.; Andes, D.R. Impact of Triazole Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Availability and Timing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, doi:10.1128/AAC.01245-19.

- Pierce, C.G.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Lazzell, A.L.; Powell, A.T.; Saville, S.P.; McHardy, S.F.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. A Novel Small Molecule Inhibitor of Candida albicans Biofilm Formation, Filamentation and Virulence with Low Potential for the Development of Resistance. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2015, 1, doi:10.1038/npjbiofilms.2015.12.

- Romo, J.A.; Pierce, C.G.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Lazzell, A.L.; McHardy, S.F.; Saville, S.P.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Development of Anti-Virulence Approaches for Candidiasis via a Novel Series of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Candida albicans Filamentation. mBio 2017, 8, doi:10.1128/mBio.01991-17.

- Vila, T.; Romo, J.A.; Pierce, C.G.; McHardy, S.F.; Saville, S.P.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Targeting Candida albicans filamentation for antifungal drug development. Virulence 2017, 8, 150–158, doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1197444.

- Pierce, C.G.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Candidiasis drug discovery and development: New approaches targeting virulence for discovering and identifying new drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2013, 8, 1117–1126, doi:10.1517/17460441.2013.807245.

- Bastidas, R.J.; Shertz, C.A.; Lee, S.C.; Heitman, J.; Cardenas, M.E. Rapamycin exerts antifungal activity in vitro and in vivo against Mucor circinelloides via FKBP12-dependent inhibition of Tor. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 270–281, doi:10.1128/EC.05284-11.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Tan, J.; Sun, Y.; Wan, Z.; Li, R. Antifungal activity of geldanamycin alone or in combination with fluconazole against Candida species. Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 273–279, doi:10.1007/s11046-012-9612-1.

- Zhai, B.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Sachs, M.S.; Lin, X. The antidepressant sertraline provides a promising therapeutic option for neurotropic cryptococcal infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3758–3766, doi:10.1128/AAC.00212-12.

- Koselny, K.; Green, J.; DiDone, L.; Halterman, J.P.; Fothergill, A.W.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, T.F.; Cushion, M.T.; Rappelye, C.; Wellington, M.; et al. The Celecoxib Derivative AR-12 Has Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity In Vitro and Improves the Activity of Fluconazole in a Murine Model of Cryptococcosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 7115–7127, doi:10.1128/AAC.01061-16.

- Dolan, K.; Montgomery, S.; Buchheit, B.; Didone, L.; Wellington, M.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal activity of tamoxifen: In Vitro and In Vivo activities and mechanistic characterization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3337–3346, doi:10.1128/AAC.01564-08.

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, T.F.; Srinivasan, A.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Fothergill, A.W.; Wormley, F.L.; Ramasubramanian, A.K.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Repurposing auranofin as an antifungal: In Vitro activity against a variety of medically important fungi. Virulence 2017, 8, 138–142, doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1196301.

- Siles, S.A.; Srinivasan, A.; Pierce, C.G.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Ramasubramanian, A.K. High-throughput screening of a collection of known pharmacologically active small compounds for identification of Candida albicans biofilm inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3681–3687, doi:10.1128/AAC.00680-13.

- Wall, G.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, H.P.; Patterson, T.F.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Screening a Repurposing Library for Inhibitors of Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris Identifies Ebselen as a Repositionable Candidate for Antifungal Drug Development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, doi:10.1128/AAC.01084-18.

- Wall, G.; Herrera, N.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Repositionable Compounds with Antifungal Activity against Multidrug Resistant Candida auris Identified in the Medicines for Malaria Venture’s Pathogen Box. J. Fungi 2019, 5, doi:10.3390/jof5040092.

- De Oliveira, H.C.; Monteiro, M.C.; Rossi, S.A.; Peman, J.; Ruiz-Gaitan, A.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S.; Mellado, E.; Zaragoza, O. Identification of Off-Patent Compounds That Present Antifungal Activity Against the Emerging Fungal Pathogen Candida auris. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 83, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2019.00083.

- Yousfi, H.; Ranque, S.; Cassagne, C.; Rolain, J.M.; Bittar, F. Identification of repositionable drugs with novel antimycotic activity by screening Prestwick Chemical Library against emerging invasive molds. J. Glob. Antimicrob Resist. 2020, doi:10.1016/j.jgar.2020.01.002.

- Butts, A.; DiDone, L.; Koselny, K.; Baxter, B.K.; Chabrier-Rosello, Y.; Wellington, M.; Krysan, D.J. A repurposing approach identifies off-patent drugs with fungicidal cryptococcal activity, a common structural chemotype, and pharmacological properties relevant to the treatment of cryptococcosis. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 278–287, doi:10.1128/EC.00314-12.

- Watamoto, T.; Egusa, H.; Sawase, T.; Yatani, H. Screening of Pharmacologically Active Small Molecule Compounds Identifies Antifungal Agents Against Candida Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1453, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01453.

- Kim, K.; Zilbermintz, L.; Martchenko, M. Repurposing FDA approved drugs against the human fungal pathogen, Candida albicans. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015, 14, 32, doi:10.1186/s12941-015-0090-4.

- Wall, G.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Screening Repurposing Libraries for the Identification of Drugs with Novel Antifungal Activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, doi:10.1128/AAC.00924-20.

- Lee, N.Y.; Ko, W.C.; Hsueh, P.R. Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Organisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1153, doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01153.

- Beyth, N.; Houri-Haddad, Y.; Domb, A.; Khan, W.; Hazan, R. Alternative antimicrobial approach: Nano-antimicrobial materials. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, doi:10.1155/2015/246012.

- Panacek, A.; Kolar, M.; Vecerova, R.; Prucek, R.; Soukupova, J.; Krystof, V.; Hamal, P.; Zboril, R.; Kvitek, L. Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles against Candida spp. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6333–6340, doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.065.

- Vazquez-Munoz, R.; Avalos-Borja, M.; Castro-Longoria, E. Ultrastructural analysis of Candida albicans when exposed to silver nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108876, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108876.