The electro-oxidation of olive mill and biodiesel wastewaters in an alkaline medium with the aim of hydrogen production and simultaneous reduction in the organic pollution content are presented. The process is performed, at laboratory scale, in an own-design single cavity electrolyzer with graphite electrodes and no membrane. The system and the procedures to generate hydrogen under ambient conditions are described. The gas flow generated is analyzed through gas chromatography. The wastewater balance in the liquid electrolyte shows a reduction in the chemical oxygen demand (COD) pointing to a decrease in the organic content. The experimental results confirm the production of hydrogen with different purity levels and the simultaneous reduction in organic contaminants. This wastewater treatment appears as a feasible process to obtain hydrogen at ambient conditions powered with renewable energy sources, resulting in a more competitive hydrogen cost.

1. Introduction

At present, a considerable rise in world energy demand is under way due to population growth and the expansion of economies, mainly emerging ones. This implies a large growth in pollution, resulting in ever-larger green house gas emissions and global warming of the planet, with a consequent increase in the Earth’s average temperature.

The need for a change in the world energy system and for an improvement in energy efficiency is obvious. Thus, the demands for efficient use of limited resources and the development of environmentally acceptable technologies are increasing, due to growing social awareness of reusing and recycling wastes.

Every day tons of wastewater are generated all over the world, for which no single treatment is able to reduce the water’s contaminants to the permitted limits. Wastewater management is a challenge for many countries, as it is essential for human health, the environment, and sustainable economic development. The idea of using organic wastewater as a hydrogen source has arisen due to the difficulties in treatment of organic wastes. In addition, hydrogen generation is increasingly relevant due to its multiple applications and CO2 zero emissions.

1.1. Hydrogen Economy

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, but is rarely found in a free form on Earth because of its chemical affinity. Usually, it appears combined with other elements, giving rise to compounds such as water, hydrides, or organic materials. It is an element having a higher energy yield, of 122 KJ/g. Hydrogen is not strictly an energy source, but a flexible energy carrier, which can be produced both from any primary energy source and locally available materials, such as biomass, wind, solar, geothermal, and organic waste

[1][2].

For several years, the hydrogen vector concept has been developed as a complement to the electricity vector. Its main advantage over electricity is that it can be stored as a chemical energy support in gaseous, liquid, and solid (metal hydrides) phases. Stored hydrogen significantly benefits the reduction in gas emissions in the automotive sector, and aids in the decarbonization of industrial processes. In addition, it represents a high enthalpy storage mechanism for non-controllable renewable energy sources for real-time coupling of power flow generation and demand. Furthermore, fuel cells can transform hydrogen into electricity, as an energy source for applications that currently use fossil fuels.

Hydrogen production processes have their origin in a wide variety of raw materials.

Table 1 shows the main energy sources, renewable or otherwise, and some processes used for hydrogen production. Each of these technologies is at a different stage of development and offers different benefits, opportunities, and challenges. Most of these technologies are already commercially available for large-scale hydrogen industrial production

[1][2]. Other hydrogen production processes are still under development, such as the method here presented.

Table 1. Primary energy sources and more-developed techniques of hydrogen production.

| Energy Primary Sources |

Hydrogen Production Processes |

Marine

Solar photovoltaic

Wind

Hydraulics

Geothermal |

Electrolysis |

| Solar thermal |

Thermo-chemistry |

| Nuclear |

| Algae |

Photosynthesis |

Petroleum

Natural gas

Coal |

Gasification |

Petroleum

Natural gas |

Steam reformed or partial oxidation |

Biogas

Bio-fuel |

| Biomass |

Pyrolysis |

As there is not yet a wide market for hydrogen energy applications, more than 90% of the hydrogen generated is used on-site in the refinery industry, for desulphurization, in the chemical industry, as a chemical reagent for ammonia and fertilizer production, and in methanol production, with only 10% being used for other purposes

[1][2]. Hydrogen demand in 2020 was about 90 Mt, with more than 70 Mt used as pure hydrogen and less than 20 Mt blended with carbon-containing gases in both methanol production and steel manufacturing.

In 2020, the majority of hydrogen produced was obtained from fossil fuels (68.64%; 60.53 Mt), by-products in refineries (21.09%; 18.6 Mt) or fossil with carbon capture and utilization (9.24%; 8.15 Mt); in contrast, the hydrogen production by fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage (0.8%–0.71 Mt) and electrolysis (0.56%–0.49 Mt) was much lower

[3]. The latter method, although less developed, holds great promise since, combined with renewable energy sources, it will considerably reduce the carbon footprint. Hydrogen produced from fossil fuels results in close to 900 Mt of CO

2 emissions per year

[3].

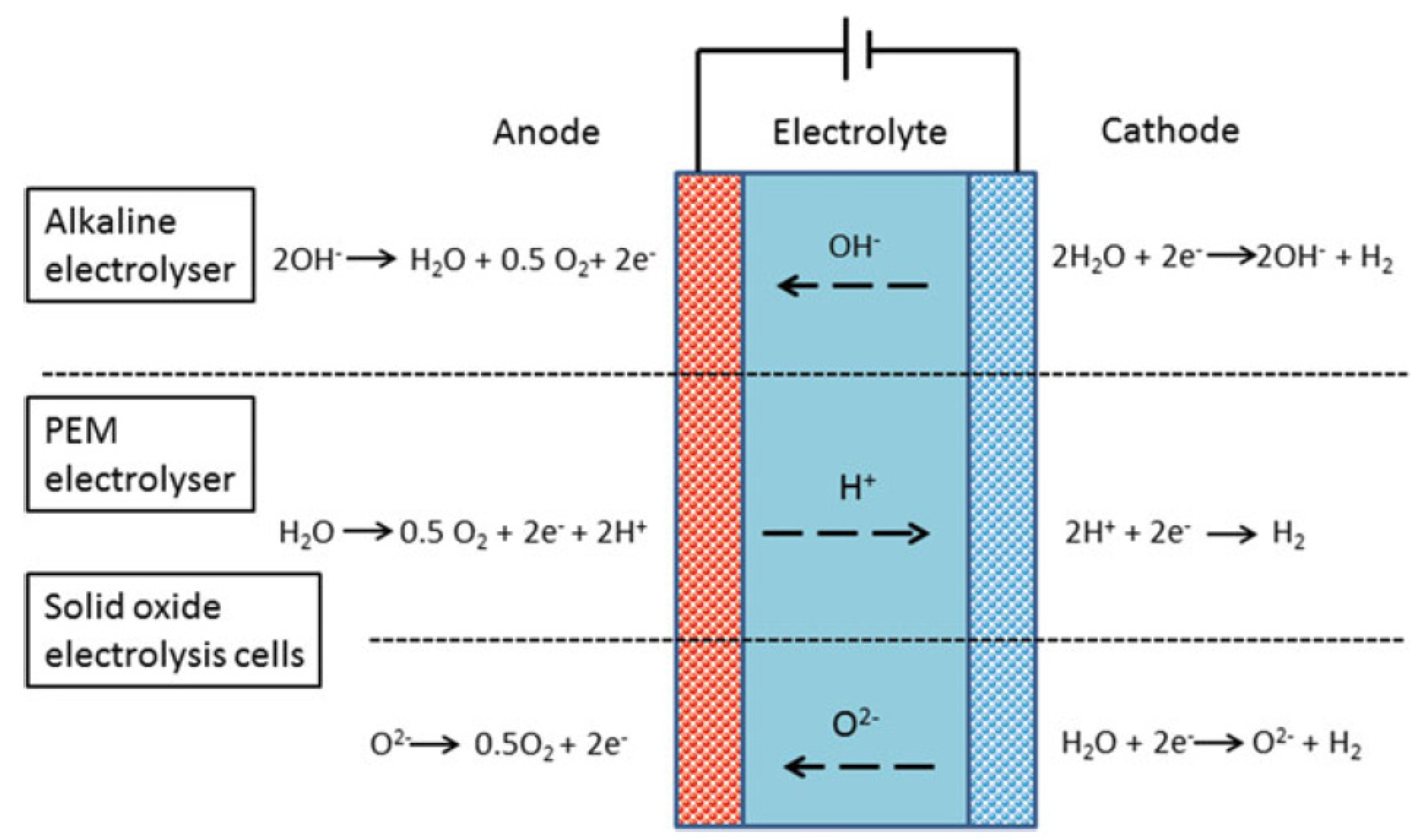

Electrolysis is being extensively studied and used for “green H

2” production, despite its negative energy balance

[4], since the energy requirement for water electrolysis with an alkaline electrolyzer is 51 kWh/kg H

2 [5], whereas the energy content of hydrogen gas is 33.2 kWh/kg H

2, having adensity of 0.08988 kg/Nm

3 [6].

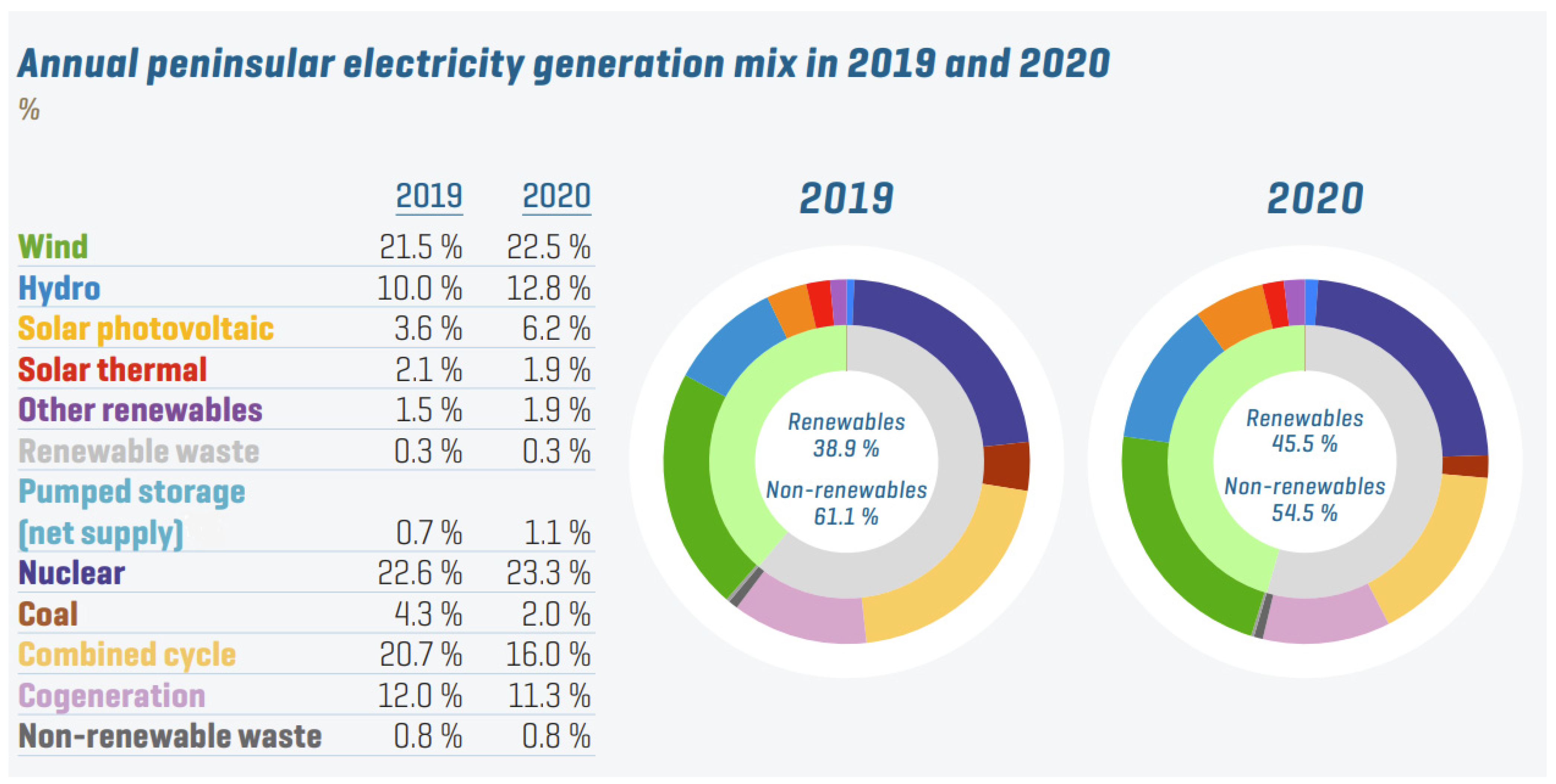

The electricity generation mix of peninsular Spain during 2019 and 2020 is displayed in

Figure 1 [7]. Renewable energy may increase considerably with the introduction of the hydrogen vector into the system. Coal and gas still supply around 20% of the energy, and their substitution is essential to avoid CO

2 emissions.

Figure 1. Peninsular Spain electricity generation mix in 2019 and 2020 (%)

[7].

The EU Member States have signed and ratified the Conference of the Parties (COP21) Paris agreement to keep global warming “well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius”. This requires virtually carbon-free power generation, increased energy efficiency, and the deep decarbonization of main consumers: transport, buildings, and industry. An ambitious scenario for hydrogen deployment in the EU is the achievement of approximately 2250 terawatt hours (TWh) of hydrogen by 2050, representing roughly one-quarter of the EU’s total energy demand. Concerning power generation, buildings, and industry, this scenario would result in a mix of about 70% centralized water electrolysis, approximately 20% decentralized water electrolysis, and 5% steam methane reforming in 2050. For transportation, 95% of hydrogen is expected to be generated with water electrolysis, half of which will use decentralized water electrolysis. Biogas technology will complete this scenario by providing the remaining 5%

[8].

The hydrogen economy aims to produce green hydrogen through the electrolysis process, but the cost is still higher than that through the gasification process. As hydrogen production from wastewater electrolysis is still one of the most expensive methods, at 7.59 USD/kg H

2 [9], a great challenge remains to investigate more efficient and simpler methods to achieve competitive prices.

1.2. Wastewater: Impact and Types

Among the multiple organic residues, olive mill and biodiesel wastewaters are part of the residual waters group within residual organic liquids.

Most urban, farming, and industrial activities require a large amount of water, which leads to the generation of a large quantity of wastewater. Most wastewaters are spilled onto the environment without any treatment due to weak regulations. This has a detrimental impact on human health, economic productivity, freshwater resource quality, and the ecosystem.

Sources of generated wastewater include domestic residences, commercial properties, industrial operations, cattle, and agriculture. Globally, about 80% of wastewater receives no treatment. Pollutants present in wastewater include pathogens (as bacteria, virus, and microscopic parasites), organic particles, soluble organic material, inorganic particles, toxins (e.g., herbicides, pesticides, dyes, or poisons), pharmaceuticals, household wastes, and even dissolved gases

[10].

These wastewaters are a complex mixture of different organic and inorganic compounds, some of which are toxic and difficult to degrade, and are mainly treated by conventional technologies such as aerobic and anaerobic processes and chemical coagulation. As these techniques are not able to remove all of the harmful compounds, electrochemical treatments are being developed to complement them

[11].

Production processes give rise to large amounts of residual organic liquids such as beet root pulp, palm oil mill effluent, and wastewater from dairies, rice mills, chemicals, sago (large leaf palm), biomethanated distillate, paper and pulp, cheese whey, textile desizing, cassava, olive mills, protein, breweries, and biodiesel

[10].

Several research groups have used similar techniques to treat wastewater. Lv et al. reported on a NiFeMo hybrid film that acts as cathode and anode materials in an electrolytic cell for hydrogen generation from urea electrolysis and the purification of urea-containing wastewater. They provide an easy method for synthesizing low-cost high-performance electro-catalysts

[12].

Nitrate contamination from industrial wastewater has become a common environmental problem. Yao et al. analyzed the electrochemical reduction in

NO−3 from wastewater, aiming to enhance the efficiency of

NO−3 elimination and the selectivity of

NO−3 to N

2. Results indicated that acidic conditions were suitable for direct and indirect nitrate reduction, while

NO−3 was mainly reduced via direct reduction under alkaline conditions

[13].

Marks et al. used a laboratory-scale reactor to study the feasibility of the energetic valorization of winery effluents into hydrogen by means of dark fermentation and its subsequent conversion into electrical energy using fuel cells. The acidogenic fermentation generated a gas effluent composed of CO

2 and H

2 (55%), resulting in a hydrogen yield about 1.5 L per liter of fermented wastewater at standard conditions

[14].

Louhasakul et al. presented an integrated bio-refinery concept combining two biological platforms for the valorization of palm oil mill effluents and for simultaneous production of high market value products, such as microbial oils and bio-energy. Palm oil mill effluents were aerobically fermented to produce lipids, and subsequently the effluent from the fermentation was used as influent feedstock in an anaerobic digester for biogas production. A maximum of 74% of the theoretical methane yield was achieved during continuous reactor operation

[15].

Other applications use microbial electrochemical cells (MECs) to produce renewable hydrogen and, simultaneously, wastewater treatment. Krishnan et al. indicated that MEC have the potential to convert organic wastewater into hydrogen and value-added chemicals such as methane, ethanol, and hydrogen peroxide. Compared to other conventional methods, MECs offer a high H

2 yield with a small energy input of 0.4–0.5 V. The principal components of the MEC are similar to those of the electrolysis process, i.e., the anode and cathode electrodes, semi-permeable membrane, electrochemically active microbes, and the power supply unit. Several types of wastewater, such as agricultural, domestic, and industrial wastewater, were analyzed

[16].

Kadier et al. showed that microbial electrolysis cells of palm oil mill effluents for biological H

2 production can be successfully derived using modeling processes. These findings indicate that the maximum H

2 production rate can be affected by the incubation temperature, the initial pH, or the influent dilution rate. Experimental analysis revealed that under the optimum conditions of T = 30.23 °C, pH = 6.63, and a 50.71% dilution rate of the influent, a maximum hydrogen production rate of 1.1747 m

3 H

2/m

3 of solution was achieved

[17].

1.2.1. Olive Mill Wastewater

Every year, around 15 million tons of olive mill wastewater are generated all over the world

[18]. Olive mill wastewater has a high organic load, measured by its Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) or its Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), which is much higher than that of the effluents from other agri-food industries

[19]. Organic matter consumes oxygen from the water and prevents fish life, so must be treated before being spilled into rivers or used for other purposes. Furthermore, it also shows a high content of inhibitory compounds such as phenolic compounds, whose characterization and treatment have not been sufficiently addressed

[20].

1.2.2. Biodiesel Wastewater

Biodiesel wastewater is a residue from the washing processes used to remove excess contaminants and impurities to obtain high quality biodiesel that meets international standard specifications. The characteristics of this wastewater include a high pH, high level of hexane-extracted oil, and low concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus, which hinder its natural degradation, because these values are unfavorable for the growth of microorganisms. As the main component of biodiesel wastewater is residual oil, discharges into public drainage may block drains and disturb the biological activity in sewage treatment.

The large amount of biodiesel wastewater generated by the commonly used wet-washing process is drawing the attention of researchers. The washing process, repeated two to five times, depends on the impurity level of methyl ester. Biodiesel production of 100 L yields about 20–120 L of wastewater. In Thailand, biodiesel production of more than 350,000 L/day generates more than 70,000 L/day of wastewater

[21].

Previous studies have found that biodiesel from transesterification contains glycerol, soap, methanol, free fatty acids (FFAs), catalysts, and glycerides. These contaminants contribute to its high contents of COD, suspended solids (SS), and oil and grease (O&G), and depend on the process type

[21].

1.2.3. Recycling and Disposal

When pouring processed wastewater into a sewage system, the same regulations as those for urban wastewater are applied. The wastewater requirements after treatment, according to Spanish regulations, are shown in Table 2. The concentration value or the percentage reduction is applied.

Table 2. Maximum concentrations and minimum percentage reductions for contaminant parameters

[22].

| Parameter |

Concentration |

Minimum % of Reduction |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (DOB 5) |

25 mL/L O2 |

70–90 |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) |

125 mL/L O2 |

75 |

| Total suspended solids (TSS) |

35 mL/L |

90 |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/en15165888