Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a global public health issue which poses a substantial humanistic and economic burden on patients, healthcare systems and society. In recent years, intestinal dysbiosis has been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of CRC, with specific pathogens exhibiting oncogenic potentials such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli and enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis having been found to contribute to CRC development. More recently, it has been shown that initiation of CRC development by these microorganisms requires the formation of biofilms. Gut microbial biofilm forms in the inner colonic mucus layer and is composed of polymicrobial communities. Biofilm results in the redistribution of colonic epithelial cell E-cadherin, increases permeability of the gut and causes a loss of function of the intestinal barrier, all of which enhance intestinal dysbiosis. This literature review aims to compile the various strategies that target these pathogenic biofilms and could potentially play a role in the prevention of CRC. We explore the potential use of natural products, silver nanoparticles, upconverting nanoparticles, thiosalicylate complexes, anti-rheumatic agent (Auranofin), probiotics and quorum-sensing inhibitors as strategies to hinder colon carcinogenesis via targeting colon-associated biofilms.

- gut biofilm

- microbiota

- colorectal cancer

- chemoprevention

- quorum-sensing

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a global public health issue. According to The Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) database, CRC is the second most diagnosed cancer among females and third among males [1]. Current statistical data show approximately 1.8 million new CRC cases were diagnosed worldwide in 2018, with 861,000 deaths which are often related to the disease only being diagnosed at advanced clinical stages [2]. These figures make CRC the third most diagnosed malignancy and second leading cause of death due to cancer globally [1]. The cost of CRC treatment worldwide is also escalating. Therefore, a lot of effort has been put into looking for preventive methods which are more cost-effective. Recent studies have also shown a new risk factor, the formation of bacterial biofilm, which has been shown to be linked to the progression of CRC [3][4][5][6]. Biofilm formation is necessary for bacterial adhesion and growth; it occurs with the production of an extracellular polymer and adhesion matrix, and this causes a change in bacterial growth and gene expression. These polymicrobial biofilms act as a trigger for pro-carcinogenic inflammatory responses which eventually lead to the development of CRC [7].

The conventional treatments of CRC include chemotherapy and surgery, both of which have significant complications. Surgery is invasive and associated with high mortality. Chemotherapeutics induce damage to DNA and initiate various signaling pathways leading to cancer cell death such as arrest of cell cycle, inhibition of DNA repair and global translation [8]. However, there are many problems with chemotherapy, including resistance to drugs, effects of cytotoxicity, and other adverse reactions. The treatment outcome also varies depending on the cancer subtype [9]. Given the high complication rate and the unpredictable response to treatment, there is a need for continuous development of better strategies for the prevention and therapy of CRC; targeting microbial biofilm could be a useful adjuvant strategy supporting the existing chemotherapy regimens for CRC by limiting their adverse effects, or by enhancing their efficacy. In this review, we will discuss and summarize the significance of gut-microbial biofilms and their role in colon carcinogenesis as well as explore the various strategies that could hinder the formation of biofilms and potentially prevent CRC, such as the use of natural extracts, probiotics, quorum-sensing inhibitors, anti-rheumatic agents (Auranofin), silver nanoparticles, upconverting nanoparticles and thiosalicylate complexes.

2. The Role of Colonic Microbiome and Biofilm in Colon Carcinogenesis

Over the past 20 years, extensive research on the human microbiome has indicated that human health, while heavily related to our own genome, is linked to a great degree on microbes which are living in and on our body [10][11][12][13]. Microbiome generally refers to the entire habitat which includes the microorganisms, their genomes and genes and the surrounding environmental conditions [14]. In the human body, the gastrointestinal tract is the site most densely populated with microorganisms—hosting about 40 trillion microbes constituting more than 1000 species, the majority of which inhabit the colon [15]. Given that they represent the largest surface area for the interactions between the host immune system and colonic microbiota, these microorganisms are expected to exert a profound influence on human physiology and metabolism. Thus, it is unsurprising that a shift of gut commensal microbiota towards opportunistic pathogens will negatively impact the physiological functions and serve as a primary driver for intestinal inflammation which increases the risk of CRC [16].

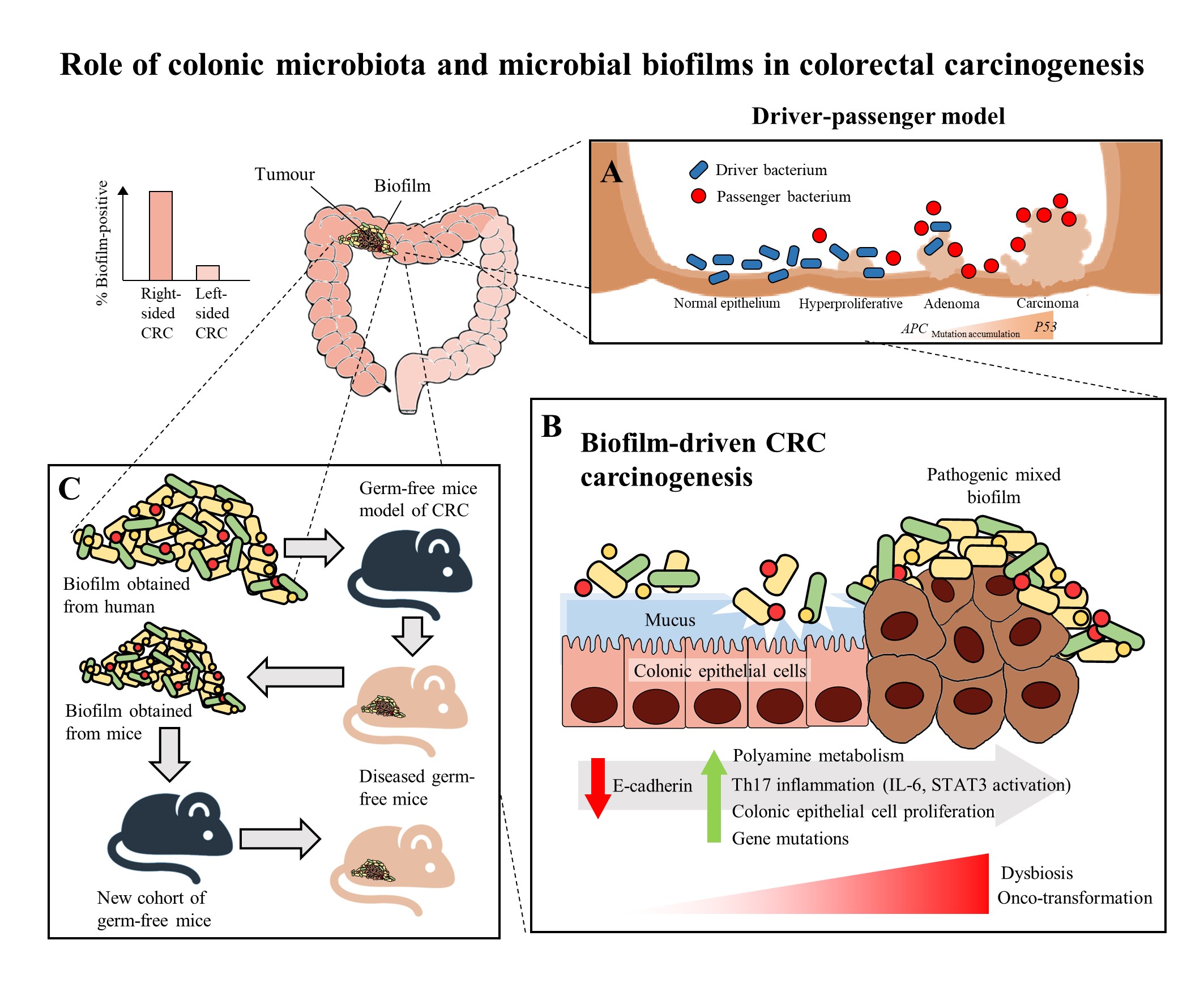

In recent years, multiple studies have shown that there are specific microorganisms which are associated with the development of CRC, and these microorganisms play a role in inducing tumorigenesis in genetically susceptible murine models of disease [17][18][19]. These results further led to the identification of microorganisms which harbor pro-oncogenic genes associated with CRC, which includes Fusobacterium nucleatum through its expression of FadA and Fap2 adhesins [20], Escherichia coli through its virulence factors that allows it to harbour genomic pks islands [21] and enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis through its expression of the B. fragilis toxin (BFT) [22]. In the development of CRC, it was proposed that the keystone pathogens, such as B. fragilis, act as the main drivers in CRC initiation via their direct genotoxic effects, leading to a T helper type 17 (Th17) inflammatory response in the colon [22]. The recruitment of immune cells releases genotoxic oxygen radicals which can cause multiple DNA double-strand breaks, resulting in an inflammation-driven carcinogenesis [23][24]. This would also lead to an increased proliferation of intestinal epithelium due to the activation of proto-oncogenes and mutations of tumor-suppressor genes. As a result, the cumulative effects of the sustained inflammation and epithelial hyperplasia together with host genetic factors associated with CRC susceptibility further drive the initiation of CRC. Moreover, the Th17-dependent inflammation induced by the driver pathogens may alter the tumor microenvironment and generate novel ecological niches for opportunistic pathogens (passenger pathogens) which eventually outcompetes the driver bacteria during CRC progression. Tjalsma, et al. [25] described this process as the “bacterial driver-passenger model”, thereby the passenger pathogens such as Fusobacterium spp. or Streptococcus spp. gradually colonize the colonic mucosa leading to intestinal microbial dysbiosis and causing CRC progression (Figure 1A). Although current evidence has shown that F. nucleatum appears to be actively involved in the later stages of CRC progression [3][20], the definite role of F. nucleatum as a passenger or a driver is still elusive. Earlier, Kostic, et al. [26] showed that F. nucleatum plays a vital role as a driver capable of promoting CRC progression, where the mutated adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene is required for F. nucleatum in inducing CRC progression in a mice model.

The human colon is surrounded completely by a protective mucus barrier comprised largely of mucins, particularly, mucin 2 (MUC2), which prevent the colonic epithelium of the host from coming into direct contact with the microbiota. It functions to separate the commensal bacteria from the host epithelium while the outer, non-attached layer acts as the natural habitat for the commensal bacteria. This mucus barrier allows normal intestinal microbiota to inhabit the colonic mucus without activating an inflammatory response [27]. When there is a breach in the protective mucus barrier, this allows the microbiota to come into contact with the colonic epithelium and this has been suggested to be an important step that initiates modifications in the epithelial cells causing intestinal inflammation [28]. The increased access to the colonic epithelium causes modification of the microbial community relationships, thereby changing the microbial composition and activity, often resulting in the formation of a biofilm [27][29]. Biofilms refer to polymicrobial communities which are enclosed in a matrix that forms on abiotic and biotic surfaces. It starts with microcolonies (small aggregation of bacterial cells) attaching to the surfaces and these adherent microcolonies then form mature biofilms when they become encapsulated in a matrix composed of self-secreted polysaccharides [30]. Having the ability to form biofilms, confers to these polymicrobial communities increased tolerance to antibacterial drugs and immune clearance [31]. Nutrients and water are also held by the embedded bacterial communities in the matrix of the biofilm [32]. Hence, biofilms favor the survival and persistence of the polymicrobial communities.

Figure 1. The role of colonic microbiota and biofilm in colorectal cancer (CRC) carcinogenesis. (A) The driver-passenger model for CRC carcinogenesis [25]. (B) Biofilm-driven CRC carcinogenesis. Biofilm results in loss of colonic epithelial cell E-cadherin (consistent with disrupted intestinal barrier function), increased IL-6 expression and STAT3 activation. These microbial biofilms contribute to a pro-oncogenic and pro-inflammatory state, coupled with the increased polyamine metabolism in colonic tissues, hence resulting in dysbiosis and onco-transformation and leading to tumor progression [7]. (C) The reassociation experiment showing that the microbiota communities from human biofilm-positive mucosa (healthy or CRC patients) resulted in CRC development in a new cohort of mice, indicates these biofilm-positive microbiota communities maintained their tumorigenic capacity [3].

Recently, biofilms have been associated with the onset and progression of CRC, a feature particularly evident in the proximal colon up to the hepatic flexure (right-sided CRC). The occurrence of biofilms is more frequently seen in colonic tissue samples from CRC patients compared to healthy individuals [29]. There is a theory that the biofilms harbor different bacterial species, rather than a single solitary variant of the invading microorganism, and possibly cause increased inflammatory responses and production of bacterial-derived genotoxic compounds. Studies by Drewes, et al. [33] and Dejea, et al. [29] have revealed that the majority of sporadic CRC patients with colonic tumors proximal to the hepatic flexure harbored mucosal biofilms while only a small portion of CRC patients with tumors distal to the hepatic flexure had biofilms. These observations may explain the poorer prognosis of right-sided CRC [34] as the biofilm-positive CRC may have additional serious epithelial tissue injury and intestinal inflammation [7]. Despite that, mucosal biofilms were also found in about 13% of healthy individuals who underwent routine screening colonoscopy. However, these studies did not investigate the cause-and-effect relationship between cancer-associated biofilms and CRC carcinogenesis, but merely demonstrated a novel and compelling perspective in illustrating the involvement of microbial biofilms as a holistic entity rather than proving a causal association of a specific microbial pathogen [35].

There have been numerous mechanisms proposed to illustrate the role of mucosal biofilms in mediating the process of CRC carcinogenesis (Figure 1B). In either healthy individuals or CRC patients, the gut microbial biofilm communities are consistent with pro-oncogenic biological changes: there is an increased proliferation of colon epithelium, increased IL-6, STAT3 activation, increased synthesis of polyamine and reduction of E-cadherin [6][29]. The increased levels of polyamine metabolites were suggested to act synergistically to promote biofilm formation and cellular proliferation, creating conditions conducive to oncogenic transformation in colon cells [6]. Moreover, the changes in permeability of the colonic barrier and metabolism of cells causes the microenvironment of the tumor to change in such a way that these initial pathogenic bacteria drivers gradually get replaced by tumor-foraging opportunistic bacteria pathogens with a competitive advantage in the tumor niche [25].

On the other hand, biofilms have also been detected in familial adenomatous polyposis patients who have inherited a mutation in the APC gene and are highly prone to CRC due to the development of polyps and adenoma formation as the early stage of the “adenoma-carcinoma sequence” [5]. The “adenoma-carcinoma sequence” model was developed by Fearon and Vogelstein [36], which is a multistep process that illustrates the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic mutations as the drivers for the onset and progression of CRC. Briefly, the sequence usually begins with the APC gene mutation, and ends with the P53 mutation, after which it progresses into carcinoma. Son, et al. [37] observed that the gut microbial composition is altered in ApcMin mice prior to obvious outgrowth of intestinal polyps. The ApcMin/+ mice are often used to study human colon carcinogenesis, as the mice harbor a truncated APC gene and develop multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) [38]. Therefore, Li, et al. [7] suggested that the microbial biofilm may be regarded as the driver in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence at an early stage of CRC progression.

Intriguingly, a recent murine study by Tomkovich, et al. [3], intended to delineate the causality of microbial biofilms in CRC, successfully demonstrated that the polymicrobial biofilms are carcinogenic in a preclinical in vivo experiment with the use of three genetic murine models of CRC carcinogenesis (germ-free ApcMinΔ850/+; Il10−/− or ApcMinΔ850/+ and specific pathogen-free ApcMinΔ716/+ mice). The study showed that at 12 weeks after inoculation, inocula prepared from human colon mucosa covered with biofilm induced the formation of colon tumors, primarily in the distal colon; while no colon tumors were induced by the inocula prepared from the biofilm-negative colon mucosa. Furthermore, within the first week after inoculation, the biofilm-positive human tumor homogenates, which were not seen in biopsies of healthy individuals, showed consistent invasion of the mucosal layer and formation of biofilm in mouse colons. A remarkable finding of this study was that biofilm communities from the colon biopsies of healthy individuals were as potent as biofilm communities from CRC hosts in inducing development of tumors. This finding is pertinent as the presence of polymicrobial biofilms containing the potential pathogens present an increased risk for CRC development and is regarded as a tipping point between a healthy and a diseased gut mucosa [30]. Furthermore, the latest finding also showed that similar levels of inflammation were observed in both mice inoculated with biofilm-positive and biofilm-negative control homogenates, but a lower degree of immunosuppressive myeloid cell recruitment and IL-17 production was triggered by biofilm-negative control homogenates when compared to biofilm-positive homogenates in the mice [3]. Often, infiltration by immune cells is associated with adverse clinical outcomes of CRC [39]. This shows that the colonic biofilms interact and alter the mucosal immune responses, possibly via the Th17 pathways, thereby promoting CRC carcinogenesis [3].

The carcinogenicity of biofilm-positive human tumor microbiota were further reinforced via the reassociation experiment showing the development of colon tumors in a new cohort of mice after inoculation with homogenized proximal or distal colon tissues from biofilm-positive inoculated mice (Figure 1C). This finding shows that the microbiota communities from human biofilm-positive mucosa which assembled in the first group of germ free mice maintain their tumorigenic capacity, even after being transferred to the new group of germ free mice [3]. Metatranscriptome analysis revealed differential upregulation of microbial genes which are involved in bacterial invasion of epithelial cells and the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan in the mucosa of mice associated with a biofilm-positive tumor compared to biofilm-negative biopsies [3]. Taken together, all these findings further fortify the notion that the formation of a biofilm by microbial pathogens appears to play a vital role in the induction and the progression of CRC.

3. Strategies to Target Gut Microbial Biofilms

Various antibiofilm strategies are being explored for potentially new chemopreventive agents and adjuvants against CRC by targeting gut microbial biofilms. These strategies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Strategies to target gut microbial biofilms.

|

Antibiofilm Strategies |

Antibiofilm Agents |

Findings |

References |

|

|

Natural Products |

Zerumbone |

• Antimicrobial activity against B. fragilis • Inhibit formation of B.fragilis biofilms • Complete eradication of B.fragilis biofilms • Decreases expression of bmeB12 |

MIC: 32 μg/mL |

[40] |

|

Alpha-humulene |

• Antimicrobial activity against B.fragilis • Inhibit formation and eradication • Complete eradication of B.fragilis biofilms |

MIC: 29 μg/mL |

[41] |

|

|

Coriander Essential Oil |

• high antibiofilm activity against E. coli biofilms • contains 89.73% of terpenes (shown to have antimicrobial activity) |

MIC: 1.6 μg/mL |

[42] |

|

|

Pomegranate Extract |

• Antimicrobial activity against E.coli • Inhibit formation of E.coli biofilms • Complete eradication of E.coli biofilms |

MIC: 250 μg/mL |

[43] |

|

|

Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) |

AgNPs from AgNO3 and Pandanus odorifer leaf extract |

• anticancer potential by inhibiting migration of rat basophilic leukemic cells • Antimicrobial activity against E. coli • Reduces E. coli biofilm formation |

MIC: 4 μg/mL ~87% biofilm biomass reduction at 2 μg/mL |

[44] |

|

AgNPs from Gloriosa superba aqueous leaf extract |

• Antibiofilm activity against E.coli |

~44% biofilm thickness reduction |

[45] |

|

|

Upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs) |

Modified UCNPs (coupled with antibodies, covered with a shell surface made of TiO2 modified with d-amino acids) |

• Detect specific pathogens linked to CRC • Antibiofilm activity through forming ROS and releasing d-amino acids |

na. |

|

|

Thiosalicylate Complexes |

Thiosalicylate complexes of Zn(II) and Hg(II) |

• Complete inhibition of E.coli biofilms • Antimicrobial activity against E.coli • Anti-tumour actions against colon cancer cell line HCT 116 |

MIC: 0.227 μg/mL |

[49] |

|

Anti-rheumatic agent |

Auranofin |

• Antimicrobial activity against B.fragilis • Complete eradication of B.fragilis biofilms • Inhibit formation of B.fragilis biofilms • Reduction of ompA and bmeB3 genes |

MIC: 0.25 μg/mL |

[50] |

|

Probiotics |

Clostridium butyricum NCTC 7423 Supernatant |

• Inhibit B.fragilis biofilms • Eradicate B.fragilis biofilms • Decrease metabolic activity • Reduce ompA and bmeB3 • Suppress extracellular nucleic acids and proteins |

na. |

[51] |

|

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus |

• Antibacterial activity against all E. coli • Reduce the formation of biofilm of two multi-drug resistant E. coli |

na. |

[52] |

|

|

Quorum sensing inhibitors |

Quorum sensing inhibitors |

Inhibits biofilm formations by: • Inhibition of synthesis of signal molecules • Signal scrambling (degradation or sequestration) • Interference with signal reception |

na. |

|

MIC—Minimum inhibitory concentration; na.—not available.

3.1. Natural Products

Natural products have long been a “gold mine” for therapeutic entities that exhibit a myriad of biological activities [56][57]; with many natural products having been shown to possess promising antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities [58][59]. Considering the vast diversity in chemical structures and their known bioactivities, natural products derived from plants have emerged as attractive candidates for drug development to suppress biofilm formation as well as eradicate biofilms formed by pathogens [60][61]. In this review, several plant-derived natural products recently reported to exhibit antibiofilm against the enteropathogens associated with CRC are highlighted as below.

There are a few studies of natural extracts which have shown antibiofilm effects towards biofilms containing such pathogens and could potentially be explored further in more clinical trials as alternatives for CRC prevention [62]. One of the strategies is the use of zerumbone extracted from Zingiber Zerumbet (L.) Smith which is a type of edible ginger. In the past few years, studies have suggested that zerumbone has many biological activities which promote anti-mutagenic, anti-bacterial, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory activities [63][64][65]. Recently, Kim, et al. [40] demonstrated that zerumbone exerted antibiofilm activities against different strains of B. fragilis, including the wild-type enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (WT-ETBF), btf-2 gene overexpressing ETBF and non-enterotoxigenic B. fragilis. Zerumbone was shown to inhibit biofilm formation as well as eradicate the preformed biofilm. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that zerumbone inhibited biofilm formation of B. fragilis strains containing the toxic bft-2 gene more effectively than the non-enterotoxigenic strain. Furthermore, the study suggested that the antibiofilm activity of zerumbone may be mediated via the downregulation of an efflux pump-related gene (bmeB12) which has been associated with biofilm formation [40]. Alpha-humulene is another natural product showing potential to inhibit biofilm formation by enterotoxigenic B. fragilis [41]. Alpha-humulene is a sesquiterpene found in the essential oils of aromatic plants, including Mentha spicata, Salvia officinalis and ginger family (Zingiberaceae) [66][67][68]. Alpha-humulene has been known for its anti-inflammatory actions and a few studies have shown that essential oils with α-humulene have antibacterial effects [69][70]. Similar to zerumbone, α-humulene was also shown to exert antibiofilm activity by inducing downregulation of RND-type efflux pump bmeB1 and bmeB3 genes, leading to cell membrane disruption and the suppression of biofilm formation of enterotoxigenic B. fragilis [41].

Antibiofilm effects towards biofilms produced by E. coli were seen in a study of Sauropus androgynus leaf extracts whereby both antibiofilm and antimicrobial activity were demonstrated. Through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis, these leaf extracts were found to contain phytochemicals, such as steroids, phenols, alkaloids, tannins and flavonoids, which possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer and immunomodulatory properties [71]. Bazargani and Rohloff [42] suggested coriander essential oil as a new antibiofilm agent. They studied the antibiofilm activity of essential oils and plant extracts of anise, coriander and peppermint against E. coli. Their study showed that coriander essential oil had the highest antibiofilm activity against the biofilm produced by E. coli. The presence of terpenes, such as p-cymene, octanol, geranyl acetate, α-pinene, γ-terpinene and linalool, could also be the reason coriander essential oils have a high inhibitory effect on formation of E. coli biofilms [42]. In Asian countries, pomegranate has been used in traditional medicine for treating diarrhea and dysentery for many years. There were multiple reports on the bioactive potential of pomegranate as an antibacterial, antioxidant and anticancer agent [72][73][74]. One of the studies indicated that the pomegranate extract and ellagic acid, which is its major component, exhibit antibiofilm activity against E. coli [43].

3.2. Anti-Rheumatic Agent

Auranofin is a gold salt and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis. It has been proposed to be repurposed as an antibacterial and antibiofilm agent against intestinal bacteria, such as enterotoxigenic B. fragilis, and potentially as an anti-cancer drug. Repurposing of auranofin would be cost and time efficient as it saves the time and expense needed to develop and test a new drug; given that it is already approved and has been in use for several years, its safety has already been extensively studied [50]. Recently, a study demonstrated promising results of auranofin against enterotoxigenic B. fragilis with relatively low concentrations required to inhibit and eradicate both the biofilms and bacteria [50]. Treatment with auranofin was shown to induce significant reduction of expression of the outer membrane protein (ompA) gene and the bmeB3 gene [50]; the ompA gene has been associated with the regulation of biofilm formation [75]. Future studies should be conducted to determine the efficacy of Auranofin to inhibit enterotoxigenic B. fragilis in in vivo models.

3.3. Probiotics

Several preclinical experiments demonstrated that probiotics and their derived products can be potentially developed to target carcinogenic biofilms. In these studies, antibiofilm properties of cocktails of different probiotic strains were evaluated against the biofilm-growing enteropathogens, including enterotoxigenic B. fragilis and enterotoxigenic E. coli strains [51][52]. The effects of the probiotic Clostridium butyricum NCTC 7423 supernatant on gene expression and formation of biofilm of enterotoxigenic B. fragilis was recently studied by Shin, et al. [51]. The cell-free supernatants (CFS) of C. butyricus exhibited antagonistic effects against the growth of enterotoxigenic B. fragilis in planktonic culture. CFS from C. butyricus also inhibited the development of biofilms, dissembled biofilms which were preformed and decreased the metabolic activity of cells in the biofilms. It was also shown to significantly reduce the expression of virulence and efflux pump related genes in enterotoxigenic B. fragilis, such as bmeB3 and ompA. In addition, CFS from C. butyricus showed the ability to significantly suppress extracellular nucleic acids and proteins within the basic components of the biofilm [51]. Furthermore, another study demonstrated a preparation of cell-free spent media (CFSM) of six probiotics which belong to the genus Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus exhibited strong antibacterial activity against all E. coli isolates and were able to suppress growth of drug-resistant E. coli. The CFSM of probiotics in this study were also able to reduce the formation of biofilm of two multi-drug resistant E. coli [52].

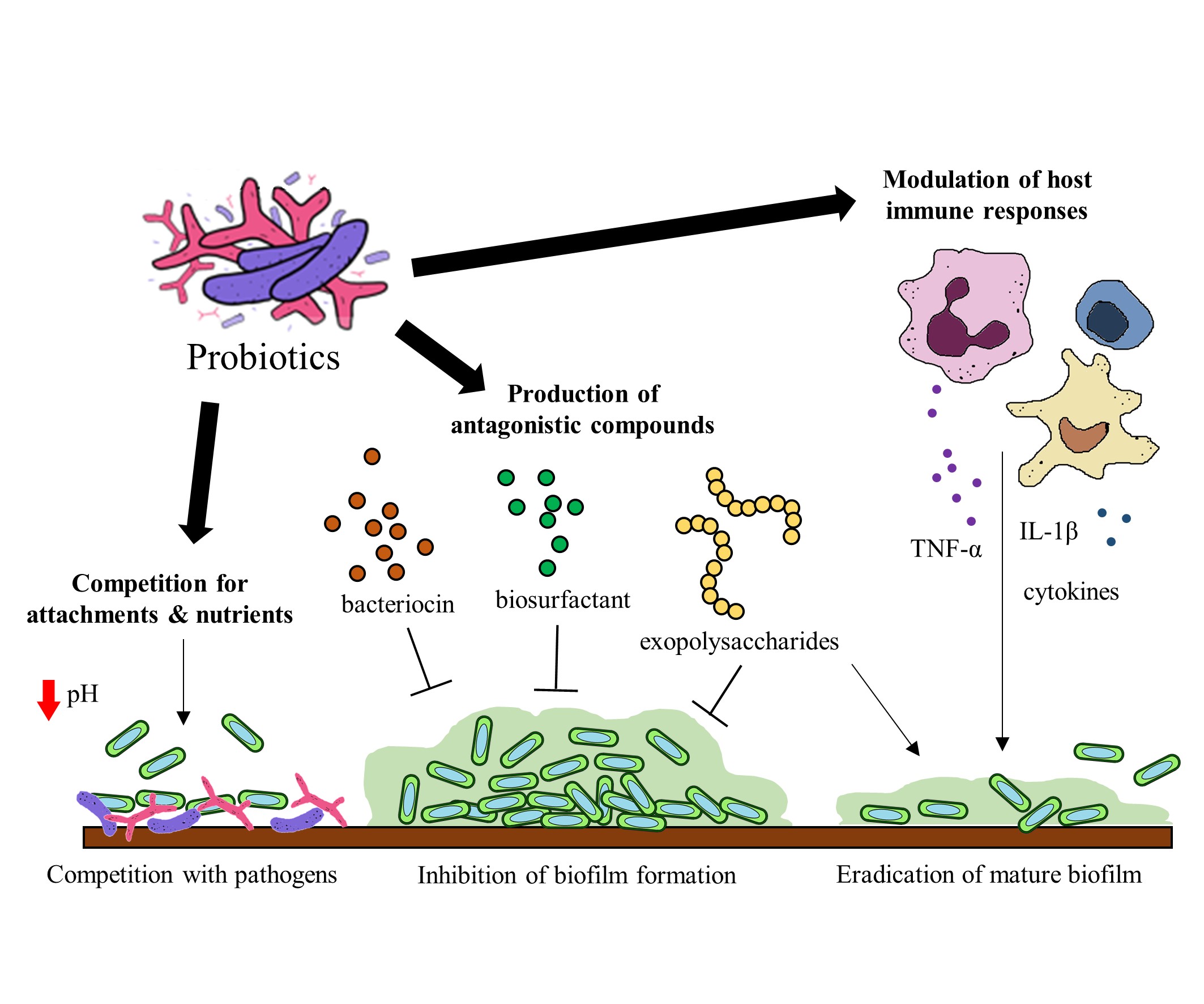

Probiotics have been identified to hinder biofilm formation and the survival of biofilm pathogens with different mechanisms. Some of these mechanisms include (a) the production of antagonistic compounds, (b) competition with pathogens and (d) modulation of host immune responses [76] (Figure 2). Probiotics can produce various antagonistic compounds, including exopolysaccharides [77], bacteriocins [78] and biosurfactants [79] which exhibit antibiofilm activity. These antagonistic compounds have been shown to interfere with biofilm attachment and formation as well as the thinning of mature biofilms. Furthermore, probiotics are capable of competing with the pathogenic bacteria for surface of attachment and nutrients by altering their surrounding pH values [80][81]. Besides the direct interactions between probiotics and the pathogens, probiotics exert immunomodulatory effects via interaction with the immune system when administered into a host. Studies suggest that probiotics and their soluble factors can regulate and activate specific immune cells and the release of cytokines via toll-like receptor recognition to elicit immunomodulatory effects[82][83].

Figure 2. Potential mechanisms of probiotics to target gut microbial biofilms.

Although promising preclinical results have been demonstrated, there is still insufficient evidence to consider probiotics as a strategy to prevent the onset or progression of CRC by means of inhibiting pathogenic biofilm formation or disrupting the pre-formed biofilms. Future studies should elucidate the molecular mechanism of probiotic action in the gut of well-designed animal models or clinical studies related to biofilm-associated CRC to provide a clearer picture of how probiotics act on the bacterial communities in biofilms and contribute to the prevention of CRC initiation and progression. At present, the intake of probiotics has shown promising results in several clinical trials and has been suggested as a viable chemopreventive approach to combat colorectal carcinogenesis via modulation of gut microbiota [84][85][86]. Based on this evidence, we can envisage that probiotic interventions represent an alternative strategy or adjuvant in the treatment of biofilm-associated diseases.

3.4. Quorum Sensing Inhibitors

Quorum-sensing (QS) inhibitors have provided new possibilities for overcoming microbial resistance and biofilm formation. QS inhibitors can work in three main ways: inhibition of the synthesis of signal molecules, degradation of QS signals or interference with signal reception for QS blockage [53]. There are a number of small-molecules have been identified to be effective in inhibiting the QS system of human pathogens, including flavonoids (apigenin, baicalein, quercetin) [87], N-decanoyl-L-homoserine benzyl ester [88] and meta-bromo-thiolactone [89]. For instance, flavonoids were demonstrated as inhibitors of both QS receptor LasR and RhlR, resulting in repression of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [87]. The genus Pseudomonas has also been shown to be a potentially opportunistic pathogen which might increase the risk of colorectal adenoma development [90]. Methylthio-DADMe-immucillin-A is another example of a QS inhibitor that has been studied for its disruption of QS of E. coli, and it does so by the inhibition of signal synthesis, suggesting a promising strategy for targeting biofilms associated with CRC progression [91].

3.5. Silver Nanoparticles

There have been various studies focusing on developing silver nanoparticles that could display bactericidal and antibiofilm actions. Several studies have adopted the emerging green synthesis approach by synthesizing AgNPs from plants, providing an inexpensive, efficient and eco-friendly alternative to the conventional NPs synthesis [44][92]. One of these studies demonstrated that biosynthesized AgNP from AgNO3 and Pandanus odorifer leaf extract using microwave irradiation exhibited antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities against E. coli. The production of exopolysaccharides and swarming mobility, which are important factors necessary in the initial attachment and maturation of biofilm, were significantly decreased upon exposure to AgNPs. Another showed that the AgNP which was green synthesized from Gloriosa superba aqueous leaf extract exhibited antibiofilm activity against E. coli [45]. Furthermore, an in vivo study indicated that the toxicity of biosynthesized AgNPs was mild, with minor effects on the liver and renal functions of the mice; nevertheless more studies should be conducted to substantiate its therapeutic use in treating biofilm-associated CRC [44].

3.6. Upconverting Nanoparticle

Upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs) are a special class of photoluminescent materials which are able to exploit the up conversion of photons [93]. UCNPs are lanthanide-doped nanocrystals that are triggered by light which have been proposed to be used to detect and treat CRC. UCNPs transform long-wavelength near infrared (NIR) excitation light into emissions with short wavelength. This allows light to penetrate deeper and have a high signal-to-noise ratio. Recent in vitro and preclinical studies indicate that with various modifications, UCNPs can pick up bacterial infection and inflammation, which usually precedes CRC. UCNPs are able to detect specific pathogens which are responsible for development of CRC [46]. For example, UCNPs coupled with an anti-Escherichia coli antibody are able to detect E.coli [46][47]. Besides use for bacterial detection, UCNPs also have antimicrobial and antibiofilm applications. When UCNPs are used as a core covered with a shell surface made of TiO2 modified with d-amino acids, the UV light can stimulate the outer TiO2 shell to form reactive oxygen species which have antibacterial actions and stimulates the release of free d-amino acids which have antibiofilm properties [46][48].

3.7. Thiosalicylate Complexes

Thiosalicylate complexes of Zn(II) and Hg(II) are proposed to be a new class of antibiofilm, antimicrobial compound with anti-tumor effects. Thiosalicylate complexes of Zn(II) and Hg(II), [Zn(SC6H4CO2)(TMEDA)]2, were shown to have potent antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities against E. coli, whereby complete degradation of E. coli biofilms was achieved at relatively small concentration of 0.227 μg/mL. Hence, the study suggested that the complexes hold great promise for the development of a new class of antibacterial and antibiofilm agents to combat the resistant pathogens [49]. Thiosalicylate complexes of Zn(II) and Hg(II), [Zn(SC6H4CO2)(TMEDA)]2, were also shown to exert anti-tumor actions against the colon cancer cell line HCT116 [49]. Thus, it is worthwhile exploring the clinical use of thiosalicylate complexes as promising agents for preventing CRC.

4. Conclusion

The formation of biofilms has been suggested to play a role in the initiation of colon carcinogenesis, and hence the inhibition or removal of such biofilms could represent a promising strategy for CRC prevention and treatment. The current research focus on biofilm inhibitors and quorum sensing inhibitors against biofilms of enterotoxigenic B. fragilis or E. coli are valuable for the future development of new drugs. Most of these studies produce promising in vitro results. As of yet, limited in vivo evidence is available and more in vivo studies are needed to further explore the potential of natural products, the anti-rheumatic agent auranofin, probiotics, quorum-sensing inhibitors, silver nanoparticles, UCNPs and thiosalicylate complexes in the prevention and treatment of CRC. It will also be worthwhile looking into methods of improving the application of those strategies in terms of their methods of delivery to the colon by modifying them and employing colon-targeted drug delivery systems to enhance their ability to target gut microbial biofilms. There should also be continuous efforts to invent new formulation technologies that can improve colon-targeted drug delivery systems.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers12082272

References

- Freddie Bray; Jacques Ferlay; Isabelle Soerjomataram; Rebecca L. Siegel; Lindsey A. Torre; Ahmedin Jemal; Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018, 68, 394-424, 10.3322/caac.21492.

- Cancer Today . Globocan. Retrieved 2020-8-15

- Sarah Tomkovich; Christine M. Dejea; Kathryn Winglee; Julia L. Drewes; Liam Chung; Franck Housseau; Jillian L. Pope; Josee Gauthier; Xiaolun Sun; Marcus Mühlbauer; et al. Human colon mucosal biofilms from healthy or colon cancer hosts are carcinogenic. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2019, 129, 1699-1712, 10.1172/jci124196.

- Hans Raskov; Kasper Noerskov Kragh; Thomas Bjarnsholt; Mahdi Alamili; Ismail Gögenur; Bacterial biofilm formation inside colonic crypts may accelerate colorectal carcinogenesis. Clinical and Translational Medicine 2018, 7, 30, 10.1186/s40169-018-0209-2.

- Christine M. Dejea; Payam Fathi; John M. Craig; Annemarie Boleij; Rahwa Taddese; Abby L. Geis; XinQun Wu; Christina E. DeStefano Shields; Elizabeth M. Hechenbleikner; David L. Huso; et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 2018, 359, 592-597, 10.1126/science.aah3648.

- Caroline H. Johnson; Christine M. Dejea; David Edler; Linh T. Hoang; Antonio F. Santidrian; Brunhilde H. Felding; Julijana Ivanisevic; Kevin Cho; Elizabeth C. Wick; Elizabeth M. Hechenbleikner; et al. Metabolism Links Bacterial Biofilms and Colon Carcinogenesis. Cell Metabolism 2015, 21, 891-897, 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.011.

- Shan Li; Sergey R. Konstantinov; Ron Smits; Maikel P. Peppelenbosch; Bacterial Biofilms in Colorectal Cancer Initiation and Progression. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2017, 23, 18-30, 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.11.004.

- Derek Woods; John J. Turchi; Chemotherapy induced DNA damage response: convergence of drugs and pathways.. Cancer Biology & Therapy 2013, 14, 379-89, 10.4161/cbt.23761.

- Xuan-Mei Huang; Zhijie Yang; Qing Xie; Zi-Kang Zhang; Hua Zhang; Junying Ma; Natural products for treating colorectal cancer: A mechanistic review.. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 117, 109142, 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109142.

- Learn-Han Lee; Hooi-Leng Ser; Tahir Mehmood Khan; Kok-Gan Gan; Bey-Hing Goh; Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib; IDDF2019-ABS-0321 Relationship between autism and gut microbiome: current status and update. Basic Gastroenterology 2019, 68, A40-A41, 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-iddfabstracts.76.

- Learn-Han Lee; Vengadesh Letchumanan; Tahir Mehmood Khan; Kok-Gan Chan; Bey-Hing Goh; Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib; IDDF2019-ABS-0322 Dissecting the gut and skin: budding association between gut microbiome in the development to psoriasis?. Basic Gastroenterology 2019, 68, A41-A41, 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-iddfabstracts.77.

- Learn-Han Lee; Hooi-Leng Ser; Tahir Mehmood Khan; Ming Long; Kok-Gan Chan; Bey-Hing Goh; Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib; IDDF2018-ABS-0239 Dissecting the gut and brain: potential links between gut microbiota in development of alzheimer’s disease?. Basic Gastroenterology 2018, 67, A18-A18, 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-iddfabstracts.37.

- Learn-Han Lee; Vengadesh Letchumanan; Tahir Mehmood Khan; Ming Long; Kok-Gan Chan; Bey-Hing Goh; Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib; IDDF2018-ABS-0240 Role of human microbiota in skin dermatitis and eczema: a systematic review. Basic Gastroenterology 2018, 67, A19-A19, 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-iddfabstracts.38.

- Julian R. Marchesi; Jacques Ravel; The vocabulary of microbiome research: a proposal.. Microbiome 2015, 3, 31, 10.1186/s40168-015-0094-5.

- Ron Sender; Shai Fuchs; Ron Milo; Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell 2016, 164, 337-340, 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.013.

- Cynthia L Sears; Wendy S Garrett; Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer.. Cell Host & Microbe 2014, 15, 317-28, 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.007.

- Franck Housseau; Cynthia L Sears; Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF)-mediated colitis in Min (Apc+/-) mice: a human commensal-based murine model of colon carcinogenesis.. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 3-5, 10.4161/cc.9.1.10352.

- Xingmin Wang; Yonghong Yang; Mark M. Huycke; Commensal-infected macrophages induce dedifferentiation and reprogramming of epithelial cells during colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 102176-102190, 10.18632/oncotarget.22250.

- Ritesh Kumar; Jennifer L. Herold; Deborah Schady; Jennifer S. Davis; Scott Kopetz; Margarita Martinez-Moczygemba; Barbara E. Murray; Fang Han; Yu Li; Evelyn Callaway; et al. Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus promotes colorectal tumor development. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006440, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006440.

- Susan Bullman; Chandra S. Pedamallu; Ewa Sicinska; Thomas E. Clancy; Xiaoyang Zhang; Diana Cai; Donna Neuberg; Katherine Huang; Fatima Guevara; Timothy Nelson; et al. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science 2017, 358, 1443-1448, 10.1126/science.aal5240.

- Janelle C. Arthur; Ernesto Perez-Chanona; Marcus Mühlbauer; Sarah Tomkovich; Joshua M. Uronis; Ting-Jia Fan; Barry J. Campbell; Turki Abujamel; Belgin Dogan; Arlin B. Rogers; et al. Intestinal Inflammation Targets Cancer-Inducing Activity of the Microbiota. Science 2012, 338, 120-123, 10.1126/science.1224820.

- Shaoguang Wu; Ki-Jong Rhee; Emilia Albesiano; Shervin Rabizadeh; XinQun Wu; Hung-Rong Yen; David L Huso; Frederick L Brancati; Elizabeth Wick; Florencia McAllister; et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nature Medicine 2009, 15, 1016-1022, 10.1038/nm.2015.

- Adrian Frick; Vineeta Khare; Gregor Paul; Michaela Lang; Franziska Ferk; Siegfried Knasmueller; Andrea Beer; Georg Oberhuber; Christoph W. Gasché; Overt Increase of Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Murine and Human Colitis and Colitis-Associated Neoplasia. Molecular Cancer Research 2018, 16, 634-642, 10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-17-0451.

- Steven H Itzkowitz; Xianyang Yio; Inflammation and Cancer IV. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the role of inflammation. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2004, 287, G7-G17, 10.1152/ajpgi.00079.2004.

- Harold Tjalsma; Annemarie Boleij; Julian R Marchesi; Bas E. Dutilh; A bacterial driver–passenger model for colorectal cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 10, 575-582, 10.1038/nrmicro2819.

- Aleksandar Kostić; Eunyoung Chun; Lauren Robertson; Jonathan N. Glickman; Carey Ann Gallini; Monia Michaud; Thomas E. Clancy; Daniel C. Chung; Paul Lochhead; Georgina L. Hold; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment.. Cell Host & Microbe 2013, 14, 207-15, 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007.

- Malin E. V. Johansson; Jessica M. Holmén Larsson; Gunnar C. Hansson; The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host-microbial interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 108, 4659-4665, 10.1073/pnas.1006451107.

- Malin E. V. Johansson; Jenny K Gustafsson; Jessica Holmén-Larsson; Karolina S. Jabbar; Lijun Xia; Hua Xu; Fayez K Ghishan; Frederic A Carvalho; Andrew T Gewirtz; Henrik Sjövall; et al. Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2013, 63, 281-291, 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303207.

- Christine M. Dejea; Elizabeth C. Wick; Elizabeth M. Hechenbleikner; James R. White; Jessica L. Mark Welch; Blair J. Rossetti; Scott N. Peterson; Erik C. Snesrud; Gary G. Borisy; Mark Lazarev; et al. Microbiota organization is a distinct feature of proximal colorectal cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 18321-18326, 10.1073/pnas.1406199111.

- Hanne L. P. Tytgat; Franklin L. Nobrega; John Deroost; Willem M. De Vos; Bowel Biofilms: Tipping Points between a Healthy and Compromised Gut?. Trends in Microbiology 2019, 27, 17-25, 10.1016/j.tim.2018.08.009.

- Ranita Roy; Monalisa Tiwari; Gianfranco Donelli; Vishvanath Tiwari; Strategies for combating bacterial biofilms: A focus on anti-biofilm agents and their mechanisms of action. Virulence 2018, 9, 522-554, 10.1080/21505594.2017.1313372.

- Hans-Curt Flemming; Jost Wingender; The biofilm matrix. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 8, 623-633, 10.1038/nrmicro2415.

- Julia L. Drewes; James R. White; Christine M. Dejea; Payam Fathi; Thevambiga Iyadorai; Jamuna Vadivelu; April Camilla Roslani; Elizabeth C. Wick; Emmanuel F. Mongodin; Mun Fai Loke; et al. High-resolution bacterial 16S rRNA gene profile meta-analysis and biofilm status reveal common colorectal cancer consortia. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2017, 3, 34, 10.1038/s41522-017-0040-3.

- Ulrich Nitsche; Bernhard Haller; Dirk Wilhelm; Helmut Friess; Franz G. Bader; Right Sided Colon Cancer as a Distinct Histopathological Subtype with Reduced Prognosis. Digestive Surgery 2016, 33, 157-163, 10.1159/000443644.

- Georgina L. Hold; Emma Allen-Vercoe; Gut microbial biofilm composition and organisation holds the key to CRC. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2019, 16, 329-330, 10.1038/s41575-019-0148-4.

- Eric R. Fearon; Bert Vogelstein; A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990, 61, 759-767, 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i.

- Joshua S. Son; Shanawaj Khair; Donald W. Pettet; Nengtai Ouyang; Xinyu Tian; Yuanhao Zhang; Wei Zhu; Gerardo G. MacKenzie; Charles E. Robertson; Diana Ir; et al. Altered Interactions between the Gut Microbiome and Colonic Mucosa Precede Polyposis in APCMin/+ Mice. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0127985, 10.1371/journal.pone.0127985.

- Yasuhiro Yamada; Hideki Mori; Multistep carcinogenesis of the colon in ApcMin/+mouse. Cancer Science 2007, 98, 6-10, 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00348.x.

- Wolf Herman Fridman; Franck Pagès; Catherine Sautès‐Fridman; Jérôme Galon; The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 298-306, 10.1038/nrc3245.

- Hye-Rim Kim; Ki-Jong Rhee; Yong-Bin Eom; Anti-biofilm and antimicrobial effects of zerumbone against Bacteroides fragilis.. Anaerobe 2019, 57, 99-106, 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.04.001.

- Hye-In Jang; Ki-Jong Rhee; Yong-Bin Eom; Antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of α-humulene against Bacteroides fragilis. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 2020, 66, 389-399, 10.1139/cjm-2020-0004.

- Mitra Mohammadi Bazargani; Jens Rohloff; Antibiofilm activity of essential oils and plant extracts against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli biofilms. Food Control 2016, 61, 156-164, 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.09.036.

- Dhamodharan Bakkiyaraj; Janarthanam Rathna Nandhini; Balakumar Malathy; Shunmugiah Karutha Pandian; Bakkiyaraj Dhamodharan; The anti-biofilm potential of pomegranate (Punica granatumL.) extract against human bacterial and fungal pathogens. Biofouling 2013, 29, 929-937, 10.1080/08927014.2013.820825.

- Afzal Hussain; Mohamed F. Alajmi; Meraj A. Khan; Syed A. Pervez; Faheem Ahmed; Samira Amir; Fohad M. Husain; Mohd S. Khan; Gouse M. Shaik; Iftekhar Hassan; et al. Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticle (AgNP) From Pandanus odorifer Leaf Extract Exhibits Anti-metastasis and Anti-biofilm Potentials. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 2019, 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00008.

- Kasi Gopinath; Shanmugasundaram Kumaraguru; Kasi Bhakyaraj; Subramanian Mohan; Kunga Sukumaran Venkatesh; Masanam Esakkirajan; Periyannan Kaleeswarran; Naiyf S. Alharbi; Shine Kadaikunnan; Marimuthu Govindarajan; et al. Green synthesis of silver, gold and silver/gold bimetallic nanoparticles using the Gloriosa superba leaf extract and their antibacterial and antibiofilm activities.. Microbial Pathogenesis 2016, 101, 1-11, 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.10.011.

- Raminder Singh; Gokhan Dumlupinar; S. Andersson-Engels; Silvia Melgar; Emerging applications of upconverting nanoparticles in intestinal infection and colorectal cancer. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1027-1038, 10.2147/ijn.s188887.

- Li Ching Ong; Lei Yin Ang; Sylvie Alonso; Yong Zhang; Bacterial imaging with photostable upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2987-2998, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.060.

- Weili Wei; Wei Bing; Dr. Jinsong Ren; Xiaogang Qu; Near infrared-caged d-amino acids multifunctional assembly for simultaneously eradicating biofilms and bacteria. Chemical Communications 2015, 51, 12677-12679, 10.1039/C5CC04729C.

- Mousumi Nayak; Ashish Kumar Singh; Pradyot Prakash; Rajni Kant; Subrato Bhattacharya; Structural studies on thiosalicylate complexes of Zn(II) & Hg(II). First insight into Zn(II)-thiosalicylate complex as potential antibacterial, antibiofilm and anti-tumour agent. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2020, 501, 119263, 10.1016/j.ica.2019.119263.

- Hye-In Jang; Yong-Bin Eom; Antibiofilm and antibacterial activities of repurposing auranofin against Bacteroides fragilis. Archives of Microbiology 2019, 202, 473-482, 10.1007/s00203-019-01764-3.

- Da-Seul Shin; Ki-Jong Rhee; Yong-Bin Eom; Effect of Probiotic Clostridium butyricum NCTC 7423 Supernatant on Biofilm Formation and Gene Expression of Bacteroides fragilis. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 30, 368-377, 10.4014/jmb.2001.01027.

- Ahmed Abdelhamid; Aliaa Esaam; Mahmoud M. Hazaa; Cell free preparations of probiotics exerted antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against multidrug resistant E. coli. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2018, 26, 603-607, 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.03.004.

- Qian Jiang; Jiashun Chen; Chengbo Yang; Jie Yin; Yehui Duan; Quorum Sensing: A Prospective Therapeutic Target for Bacterial Diseases.. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019, 2015978-15, 10.1155/2019/2015978.

- Breah LaSarre; Michael J. Federle; Exploiting Quorum Sensing To Confuse Bacterial Pathogens. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2013, 77, 73-111, 10.1128/mmbr.00046-12.

- Xihong Zhao; Zixuan Yu; Tian Ding; Quorum-Sensing Regulation of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 425, 10.3390/microorganisms8030425.

- Pui Ying Chee; Morokot Mang; Ern Sher Lau; Loh Teng-Hern Tan; Ya-Wen He; Wai-Leng Lee; Priyia Pusparajah; Kok-Gan Chan; Learn-Han Lee; Bey-Hing Goh; et al. Epinecidin-1, an Antimicrobial Peptide Derived From Grouper (Epinephelus coioides): Pharmacological Activities and Applications. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 2019, 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02631.

- Calyn Tang; Pearl Ching-Xin Hoo; Loh Teng-Hern Tan; Priyia Pusparajah; Tahir Mehmood Khan; Learn-Han Lee; Bey-Hing Goh; Kok-Gan Chan; Golden Needle Mushroom: A Culinary Medicine with Evidenced-Based Biological Activities and Health Promoting Properties. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2016, 7, 2016, 10.3389/fphar.2016.00474.

- Camille Keisha Mahendra; Loh Teng Hern Tan; Wai Leng Lee; Wei Hsum Yap; Priyia Pusparajah; Liang Ee Low; Siah Ying Tang; Kok Gan Chan; Learn-Han Lee; Bey Hing Goh; et al. Angelicin—A Furocoumarin Compound With Vast Biological Potential. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, 2020, 10.3389/fphar.2020.00366.

- Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib; Sunny Hei Wong; Hooi-Leng Ser; Acharaporn Duangjai; Jodi Woan-Fei Law; Shanti Ratnakomala; Loh Teng-Hern Tan; Vengadesh Letchumanan; Bioprospecting of Microbes for Valuable Compounds to Mankind. Progress In Microbes & Molecular Biology 2020, 3, a0000088, 10.36877/pmmb.a0000088.

- Weng-Keong Chan; Loh Teng-Hern Tan; Kok-Gan Chan; Learn-Han Lee; Bey-Hing Goh; Nerolidol: A Sesquiterpene Alcohol with Multi-Faceted Pharmacological and Biological Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 529, 10.3390/molecules21050529.

- Loh Teng Hern Tan; Learn Han Lee; Wai Fong Yin; Chim Kei Chan; Habsah Abdul Kadir; Kok-Gan Chan; Bey-Hing Goh; Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities ofCananga odorata(Ylang-Ylang). Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 2015, 1-30, 10.1155/2015/896314.

- Dexter S. L. Ma; Loh Teng-Hern Tan; Kok-Gan Chan; Wei Hsum Yap; Priyia Pusparajah; Lay-Hong Chuah; Long Chiau Ming; Tahir Mehmood Khan; Learn-Han Lee; Bey Hing Goh; et al. Resveratrol—Potential Antibacterial Agent against Foodborne Pathogens. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9, 2018, 10.3389/fphar.2018.00102.

- S.C. Santosh Kumar; P. Srinivas; Pradeep Negi; B.K. Bettadaiah; Antibacterial and antimutagenic activities of novel zerumbone analogues. Food Chemistry 2013, 141, 1097-1103, 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.021.

- Areeful Haque; Ibrahim Jantan; Laiba Arshad; Syed Nasir Abbas Bukhari; Exploring the immunomodulatory and anticancer properties of zerumbone. Food & Function 2017, 8, 3410-3431, 10.1039/c7fo00595d.

- Min-Ju Kim; Jung-Mi Yun; Molecular Mechanism of the Protective Effect of Zerumbone on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation of THP-1 Cell-Derived Macrophages. Journal of Medicinal Food 2019, 22, 62-73, 10.1089/jmf.2018.4253.

- S. Bouajaj; A. Benyamna; H. Bouamama; A. Romane; Danilo Falconieri; Alessandra Piras; B. Marongiu; Antibacterial, allelopathic and antioxidant activities of essential oil of Salvia officinalis L. growing wild in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Natural Product Research 2013, 27, 1673-1676, 10.1080/14786419.2012.751600.

- Duangsamorn Suthisut; Paul G. Fields; Angsumarn Chandrapatya; Contact Toxicity, Feeding Reduction, and Repellency of Essential Oils From Three Plants From the Ginger Family (Zingiberaceae) and Their Major Components Against Sitophilus zeamais and Tribolium castaneum. Journal of Economic Entomology 2011, 104, 1445-1454, 10.1603/ec11050.

- Shailendra S. Chauhan; Om Prakash; Rajendra C. Padalia; Vivekanand; Anil K. Pant; Chandra S. Mathela; Chemical diversity in Mentha spicata: antioxidant and potato sprout inhibition activity of its essential oils.. Natural Product Communications 2011, 6, 1373-1378, 10.1177/1934578x1100600938.

- Elizabeth S. Fernandes; Giselle F. Passos; Rodrigo Medeiros; Fernanda Marques Da Cunha; Juliano Ferreira; Maria Martha Campos; Luiz F. Pianowski; Joāo Batista Calixto; Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds alpha-humulene and (−)-trans-caryophyllene isolated from the essential oil of Cordia verbenacea. European Journal of Pharmacology 2007, 569, 228-236, 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.059.

- André Pichette; Pierre-Luc Larouche; Maxime Lebrun; Jean Legault; Composition and antibacterial activity ofAbies balsamea essential oil. Phytotherapy Research 2006, 20, 371-373, 10.1002/ptr.1863.

- Haritha Kh; Haritha Kh; Ram Rammohan; PHYTOCHEMICAL SCREENING, ANTIOXIDANT, ANTIMICROBIAL, AND ANTIBIOFILM ACTIVITY OF SAUROPUS ANDROGYNUS LEAF EXTRACTS. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2019, 12, 244-250, 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i4.31756.

- Asish K Das; Subhash C Mandal; Sanjay K Banerjee; Sanghamitra Sinha; J Das; B P Saha; M Pal; Studies on antidiarrhoeal activity of Punica granatum seed extract in rats.. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1999, 68, 205-208, 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00102-6.

- Navindra P. Seeram; Lynn S. Adams; Susanne M. Henning; Yantao Niu; Yanjun Zhang; † Muraleedharan G. Nair; David Heber; In vitro antiproliferative, apoptotic and antioxidant activities of punicalagin, ellagic acid and a total pomegranate tannin extract are enhanced in combination with other polyphenols as found in pomegranate juice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2005, 16, 360-367, 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.006.

- Mehran Haidari; Muzammil Ali; Samuel Ward Casscells; Mohammad Madjid; Pomegranate (Punica granatum) purified polyphenol extract inhibits influenza virus and has a synergistic effect with oseltamivir. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 1127-1136, 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.06.002.

- Stephen G. J. Smith; Vivienne Mahon; Matthew A. Lambert; Robert P. Fagan; A molecular Swiss army knife: OmpA structure, function and expression. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2007, 273, 1-11, 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00778.x.

- Abolfazl Barzegari; Keyvan Kheyrolahzadeh; Seyed Mahdi Hosseiniyan Khatibi; Simin Sharifi; Mohammad Yousef Memar; Sepideh Zununi Vahed; The Battle of Probiotics and Their Derivatives Against Biofilms. Infection and Drug Resistance 2020, 13, 659-672, 10.2147/idr.s232982.

- Abdelkharim Mahdhi; Nadia Leban; Ibtissem Chakroun; Sihem Bayar; Kacem Mahdouani; Hatem Majdoub; Bochra Kouidhi; Use of extracellular polysaccharides, secreted by Lactobacillus plantarum and Bacillus spp., as reducing indole production agents to control biofilm formation and efflux pumps inhibitor in Escherichia coli. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 125, 448-453, 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.10.010.

- Vivek Sharma; Kusum Harjai; Geeta Shukla; Effect of bacteriocin and exopolysaccharides isolated from probiotic on P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm. Folia Microbiologica 2017, 63, 181-190, 10.1007/s12223-017-0545-4.

- Yulong Tan; M. Leonhard; Doris Moser; Berit Schneider-Stickler; Inhibition activity of Lactobacilli supernatant against fungal-bacterial multispecies biofilms on silicone. Microbial Pathogenesis 2017, 113, 197-201, 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.10.051.

- Alessandro Bidossi; Roberta De Grandi; Marco Toscano; Marta Bottagisio; Elena De Vecchi; Matteo Gelardi; Lorenzo Drago; Probiotics Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB and Streptococcus oralis 89a interfere with biofilm formation of pathogens of the upper respiratory tract.. BMC Infectious Diseases 2018, 18, 653, 10.1186/s12879-018-3576-9.

- Sumanpreet Kaur; Preeti Sharma; Namarta Kalia; Jatinder Singh; Sukhraj Kaur; Anti-biofilm Properties of the Fecal Probiotic Lactobacilli Against Vibrio spp.. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2018, 8, 2018, 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00120.

- Fiona Long Yan Fong; Nagendra P. Shah; Pirkka Kirjavainen; Hani El-Nezami; Mechanism of action of probiotic bacteria on intestinal and systemic immunities and antigen-presenting cells. International Reviews of Immunology 2015, 35, 1-11, 10.3109/08830185.2015.1096937.

- Silvia Balzaretti; Valentina Taverniti; Simone Guglielmetti; Walter Fiore; Mario Minuzzo; Hansel N. Ngo; Judith B. Ngere; Sohaib Sadiq; P. N. Humphreys; Andrew P. Laws; et al. A Novel Rhamnose-Rich Hetero-exopolysaccharide Isolated from Lactobacillus paracasei DG Activates THP-1 Human Monocytic Cells. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2016, 83, -16, 10.1128/aem.02702-16.

- Babak Golkhalkhali; Retnagowri Rajandram; Audra Shaleena Paliany; Gwo Fuang Ho; Wan Zamaniah Wan Ishak; Che Shafini Johari; Kin Fah Chin; Strain-specific probiotic (microbial cell preparation) and omega-3 fatty acid in modulating quality of life and inflammatory markers in colorectal cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017, 14, 179-191, 10.1111/ajco.12758.

- Hideki Ishikawa; Ikuko Akedo; Toru Otani; Takaichiro Suzuki; Tomiyo Nakamura; Ikuko Takeyama; Shingo Ishiguro; Etsuo Miyaoka; Tomotaka Sobue; Tadao Kakizoe; et al. Randomized trial of dietary fiber andLactobacillus casei administration for prevention of colorectal tumors. International Journal of Cancer 2005, 116, 762-767, 10.1002/ijc.21115.

- Ashley A. Hibberd; Anna Lyra; A. C. Ouwehand; Peter Rolny; Helena Lindegren; Lennart Cedgård; Yvonne Wettergren; Intestinal microbiota is altered in patients with colon cancer and modified by probiotic intervention. BMJ Open Gastroenterology 2017, 4, e000145, 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000145.

- Jon E. Paczkowski; Sampriti Mukherjee; Amelia R. McCready; Jian-Ping Cong; Christopher J. Aquino; Hahn Kim; Brad R. Henke; Chari D. Smith; Bonnie L. Bassler; Flavonoids Suppress Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence through Allosteric Inhibition of Quorum-sensing Receptors*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292, 4064-4076, 10.1074/jbc.M116.770552.

- Yu-Xiang Yang; Zhen-Hua Xu; Yu-Qian Zhang; Jing Tian; Li-Xing Weng; Lian-Hui Wang; A new quorum-sensing inhibitor attenuates virulence and decreases antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Microbiology 2012, 50, 987-993, 10.1007/s12275-012-2149-7.

- Colleen T. O’Loughlin; Laura C. Miller; Albert Siryaporn; Knut Drescher; Martin F. Semmelhack; Bonnie L. Bassler; A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 17981-17986, 10.1073/pnas.1316981110.

- Yingying Lu; Jing Chen; Junyuan Zheng; Guoyong Hu; Jingjing Wang; Chunlan Huang; Lihong Lou; Xingpeng Wang; Yue Zeng; Mucosal adherent bacterial dysbiosis in patients with colorectal adenomas. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 26337, 10.1038/srep26337.

- V. Singh; Gary B. Evans; D. H. Lenz; J. M. Mason; Keith Clinch; S. Mee; G. F. Painter; P. C. Tyler; Richard H. Furneaux; J. E. Lee; et al. Femtomolar Transition State Analogue Inhibitors of 5'-Methylthioadenosine/S-Adenosylhomocysteine Nucleosidase from Escherichia coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 18265-18273, 10.1074/jbc.m414472200.

- Emanuel Vamanu; Mihaela Ene; Bogdan Bita; Cristina Ionescu; Liviu Craciun; Ionela Sârbu; In Vitro Human Microbiota Response to Exposure to Silver Nanoparticles Biosynthesized with Mushroom Extract. Nutrients 2018, 10, 607, 10.3390/nu10050607.

- J.F. Suyver; A. Aebischer; D. Biner; P. Gerner; J. Grimm; S. Heer; K.W. Kramer; C. Reinhard; H.U. Gudel; Novel materials doped with trivalent lanthanides and transition metal ions showing near-infrared to visible photon upconversion. Optical Materials 2005, 27, 1111-1130, 10.1016/j.optmat.2004.10.021.