1. Introduction

Among other factors, media coverage plays a critical role in developing and distributing new information. Public opinion has been shown to be impacted in ways similar to the direction taken by media in portrayals of cultured meat (CUME). Both positive and negative attitudes are likely to be developed in correlation with the way media coverage of the topic is addressed; however, those already familiar with the topic beforehand are less likely to be influenced by exactly how media present the information. A study showed information dispersion by media to have a far greater role in developing a positive perception of CUME

[1][2]. For instance, CUME coverage by media in the United States of America (USA) and Europe has frequently discussed the comparative attributes of both conventional and cultured meat

[3]. This analysis focused on conventional and cultural meat production mechanisms, food security, animal welfare practices and the impact on human health

[3][4]. The results showed that, in order to increase the acceptability of cultured meat, it would be important to inform and educate consumers about new foods and methods of production.

Similarly, unflattering coverage also impacts public perception negatively. In an analysis of Australian print media, the most common messaging about CUME was a low degree of naturalness. The speculation was that farmers were not interested in increasing consumer acceptance of CUME

[5][6]. Other similar narratives included technological dependency that could undermine the genuine process of social change and the connection of animal production with the norms of nature, i.e., that instrumentalizing meat could undermine the animal liberation movement

[7]. However, these arguments are likely resolvable with increased awareness and research. To improve the perception of cultured meat by consumers, an analogy strategy was investigated. Researchers focused on the unnatural nature of the production of other products, and then consumers were asked to evaluate cultured meat. Studies showed that, in most cases, consumers reported a change in their attitude toward cultured meat in a positive direction

[8]. Nevertheless, the low naturalness of CUME repels consumers, being connected with intuitive perception or analytical thinking that so-called test tube meat is inherently bad.

In different employed frameworks, the high-tech aspects of CUME contribute significantly less its consumption compared to social benefits and environmental and sensory attributes

[5]. Herein, it was to provide an analysis of the current state of cultured meat and the marketing content challenges and strategies used to spread CUME in the public eye.

2. Formulation–Content Strategies for Cultured Meat Products

Consumer acceptance of CUME could be enhanced with different content strategies depending on specific consumer preferences. Previous research has indicated that people perceive CUME’s benefits to society but consider it risky for themselves in terms of taste, nutrition, and safety. This disconnect has served to enhance the gap between advocacy and reduction in consumption. This gap was reported to be higher for CUME compared to other alternative proteins, although the views on categories of foods were congruent. This resulted in late or slow adoption of marketed products

[9].

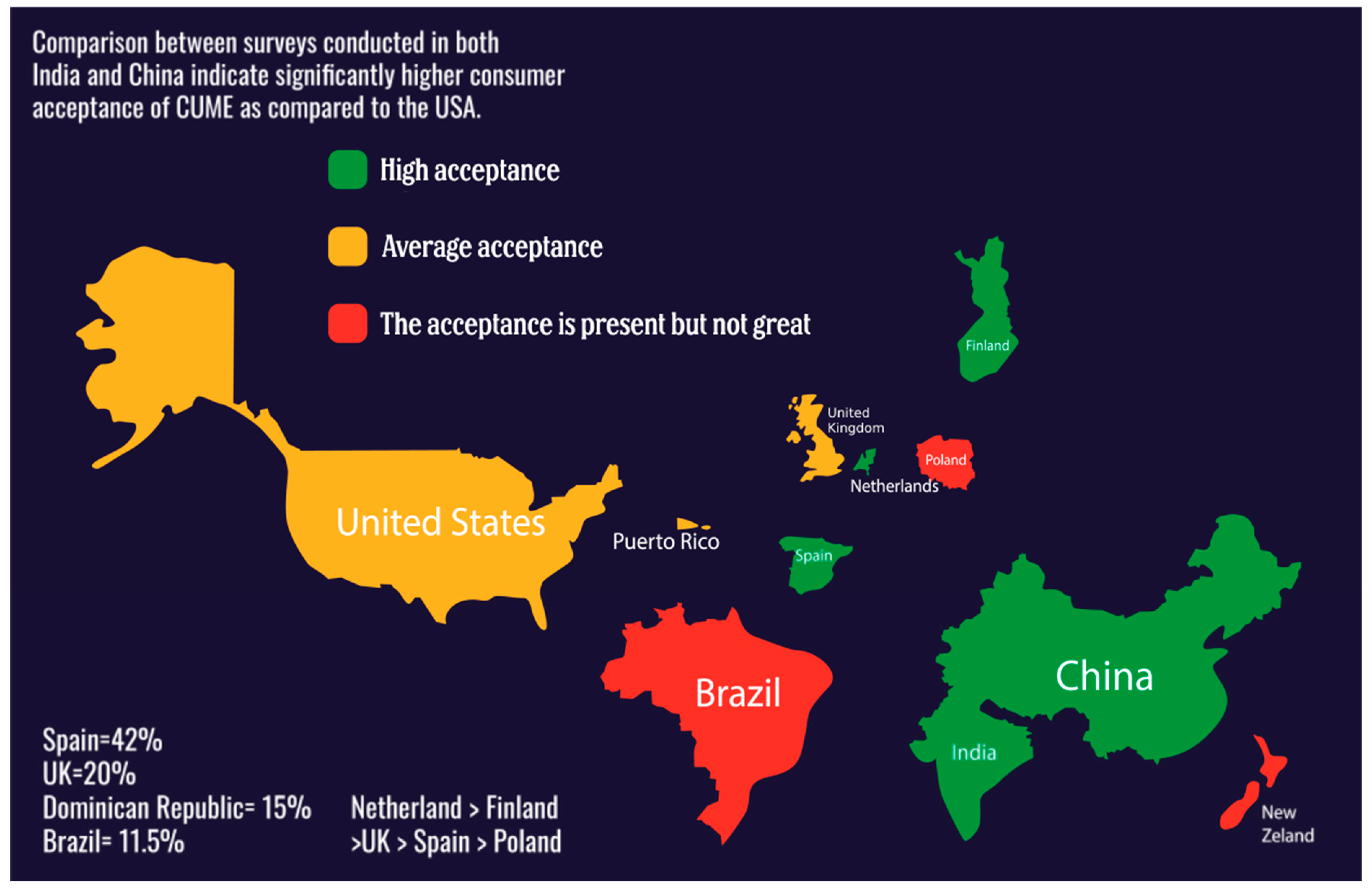

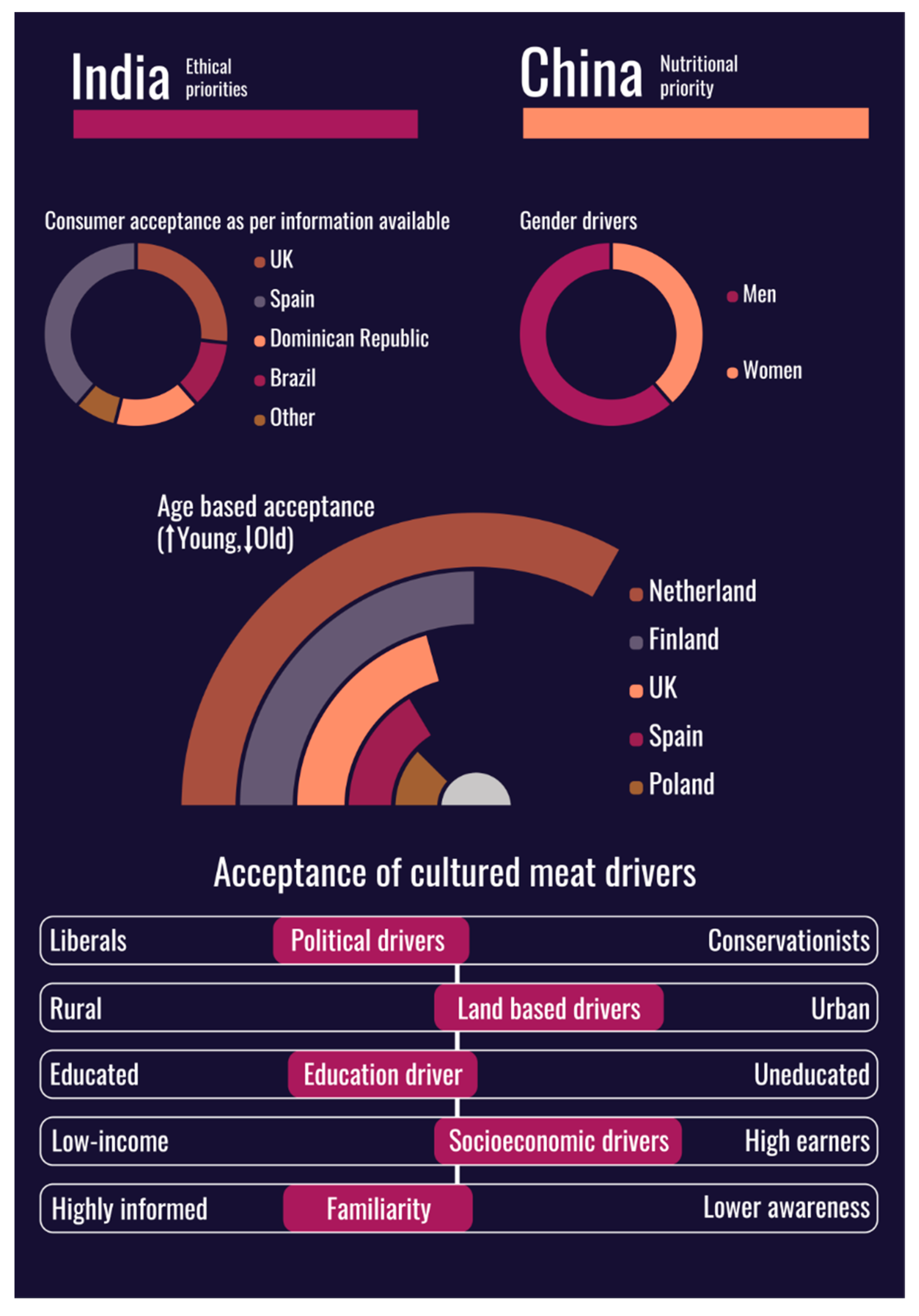

Attitudinal drivers play a significant role in different countries. Comparison between surveys conducted in both India and China indicated significantly higher consumer acceptance of CUME compared to the USA (

Figure 1). Ethical priorities have been a major driving factor in India. In China

[10], the most important factor was a healthy diet. Disgust relating to CUME turned out to be the most significant factor for US consumers. Therefore, knowing these drivers could prove useful in efforts to design marketing content strategies to address consumer responses in different countries

[11]. Another study compared attitudes among 4 countries. They recorded the highest acceptance rate in Spain (42%), followed by the UK (20%), the Dominican Republic (15%), and finally, Brazil (11.5%). Research data showed that older consumers (65+ age group) exhibited higher acceptance of CUME, as per surveys conducted in 5 European countries. In a study of five countries, the highest acceptance was observed in The Netherlands, followed by Finland, the UK, Spain, and Poland. A more traditional mindset in people was associated with a lower willingness to adopt new ideas

[10][12].

Figure 1. CUME demand characteristics by countries

[11].

Among the demographic predictors, previous and current research both indicated that age also differentiated CUME consumers. In Europe, CUME has attracted older generations (65+ years). Globally, however, CUME has attracted more young people than older people. For the latter, there was an implied societal transition; for the former, it was only considered for consumption patterns

[13]. Other than age, gender differentiation was also clear. Men were more accepting of CUME than women. Meat consumers were more likely to be interested in CUME than vegetarians, according to quite a few studies

[14][15]. They had a higher attachment to meat-based attributes and were thus more open to buying CUME. Some studies have also highlighted political orientation and its impact on consumption of CUME; liberals were considered more accepting than conservatives. Liberals also associated this consumption with other animal welfare and environmental protection-based agendas. Furthermore, youth and an urban mindset were shown to impact the likelihood of purchase of CUME products among liberal groups

[16].

Urban consumers were considered to have a greater degree of openness toward CUME in a study conducted in the Irish farming community, but this comparison warrants further research in other geographical regions before the results could be called a sustainable indication

[17].

Similarly, education was determined to be another significant indicator. Regarding socioeconomic status, some speculation has been made based on consumer inequality. Among USA consumers, results showed that CUME had greater appeal in low-income consumers. However, in New Zealand, the opposite pattern was reported

[18]. Recently, Indian consumers also displayed a pattern quite similar to that observed in New Zealand, indicating a higher consumption among high earners

[11]. The last demographic pointer considered was familiarity, which has yet to be statistically tested. This information was fortified by recently conducted studies that determined lack of knowledge to be a major hindrance in the acceptance process. Those with prior knowledge had the strongest drive toward acceptability. Lower awareness was also associated with food neophobia.

Some perceived benefits for CUME could also be employed while determining the content strategies for the product

[13]. Existing controversies of conventional meat, i.e., in terms of animal production farms, raise moral concerns among both omnivores and vegetarians. This aspect could be employed to achieve higher acceptance of consumers via effective content marketing. In Brazil, higher concerns about conventional meat production were observed, as compared to other nationalities

[19][20]. Designing marketing content that encourages consumers toward CUME using this conflict and dissonance relating to conventional meat could prove higher adaptability in the long run. An experimental study also highlighted that focusing marketing strategies on problems with existing conventional production persuaded consumers more than strategies focusing on the existing benefits of CUME

[11].

The main perceived benefit of CUME is the complete elimination of animal slaughter, as shown by a focus group study. Some were wary about growing the meat from cultured cells. Therefore, the harmless cultivation of cells, as opposed to the slaughtering of animals, could also be used to develop content strategies for a future marketing plan

[21]. Animal suffering, ethical considerations, and the death of animals are key points that have pushed consumers toward CUME in both Germany and India as per the research work

[13].

The environmental impacts of greenhouse gas reduction, lower water consumption, and land usage are also among the positive perceptions of the CUME that could be marketed further

[22]. Evidence has shown that this positive perception is hindered by the artificial or processed formation of CUME

[23]. Some consumers’ primary concern is this low naturalness discourse. A study also explained that people perceived CUME as less sustainable than other alternative proteins, concluding that CUME might impact the environment in the future

[9]. This vague concept could be resolved with enhanced awareness and education

[24].

Another major area of concern for consumers relates to potential health and food safety concerns. Among comparative studies, CUME was considered a healthier option, especially in the UK, as compared to Spain, Brazil, and Dominican Republic. A report conducted in Brazil also summarized that 24% of residents would consider buying CUME more if the health benefits and associated research were better clarified

[19][20] (

Figure 2). Therefore, addressing this knowledge in marketing content would be an appropriate way to assuage health-related uncertainties among consumers. The safety aspects of CUME have been reviewed thoroughly, as they are considered a key aspect in wide-scale adoption across countries with greater consumer awareness

[9].

Figure 2. Consumer acceptance of CUME by country.

Increased information has been speculated to be linked with food safety. i.e., food that is safe enough to be consumed. Therefore, CUME having been approved by the European Food Safety Authority could further improve public perception of its consumption. Lastly, continuing population growth has restricted resources. Human and animal n competition over land, water, and agricultural resources could also bend public opinion toward CUME. Widescale production could be used to address global hunger issues in the long term

[23]. A study conducted revealed that participants considered the possibility of ending world hunger with CUME along with its other benefits, i.e., not harming animals and safeguarding environmental integrity

[25]. This global diffusion optimism was determined to potentially lead to a higher willingness, among consumers, to embrace CUME as an alternative protein source

[26].

3. Redirecting the Perceived Barriers for Improved Marketing Strategies

Over the past few years, many reports and studies have summarized the barriers consumers perceive in relation to their adoption of CUME. Some of these impactful factors include low naturalness, safety, nutritional concerns, trust, and neophobia, as well as economic and ethical approaches. Low naturalness was the primary concern for the consumers, with its underlying roots connected to disgust, health, and safety concerns

[27]. Some qualitative studies have also highlighted this emotional objection to be a key source of CUME rejection

[28][29]. Studies indicated that this low naturalness attribute does not directly lead to the rejection of the product. CUME was considered less natural than insect protein, for instance, but was nonetheless given preference. It was also highlighted in the study that the subjective importance of naturalness resulted in lower perceived naturalness, which ultimately led to reduced consumer uptake

[1]. These results clarified that subjective importance and perceived naturalness were two different concepts that supported one opinion, i.e., agreeing to the low naturalness of CUME but perhaps considering it insignificant

[30].

Psychographic factors, including sensitivity to food hygiene, neophobia of food, and political conservative ideology, proved to be exceptions that ultimately resulted in the rejection of CUME. The qualitative study mentioned previously was conducted in the USA, while the samples tested in European territories exhibited the lowest perceived naturalness among consumers. This indicated that low naturalness might only be of importance to Europeans, rather than Americans, as per current data

[31]. Another study compared CUME with insects and concluded that insects were considered more natural than CUME

[32]. Owing to low naturalness, the next associated question focused on whether CUME was considered safe for consumption. Focus group studies, interviews of participants, and other records showed anxious attitudes toward long-term safety in terms of health effects. Therefore, research and data regarding health and safety should be made transparently available for the general public via marketing channels and content design to ease the transition. Knowledge and prior information enhanced consumer confidence in the product

[24].

The nutritional profile of CUME was considered weak compared to conventional meat types

[33]. Artificially associating CUME with unhealthiness was mentioned in a few customer concerns

[34]. The concept of healthiness varied among different individuals. Perceived health attributes were among the primary predictors among purchasers in China

[10][32].

Another key issue raised in the recent literature was consumer trust in the available product. Distrust was observed, not only in food companies, but also in labeling strategies for CUME. This trend was more prevalent in rural communities, as if it was personally connecting them with farms or conventional meat sources. Furthermore, the lack of regulatory bodies encompassing CUME further aggravated distrust. Conspiratorial ideas opposing CUME also enhanced distrust among consumers. This could be improved through food scientists and institutions engaging in direct coverage of ongoing and improving research of CUME

[16].

Another perceived barrier is the fear of everything new, or neophobia, which has been a key predictor in America, Europe and Asia. This has hindered acceptance and precluded opportunities to try new and innovative food products. Sometimes, perceived unusualness caused disgust. Studies indicated that CUME invoked less disgust than GMOs and insect consumption but more than synthetic food additives and similar food technological plant products

[35]. The emotional response of disgust is considered independent of rational evaluations. Ref.

[35] also highlighted that deviation from Western food culture invoked this disgust in response to perceived low naturalness, while other studies linked it with norm violation

[28][29]. This differentiation is crucial, as norm-violating moral disgust can be resolved in the future as CUME becomes familiar to more people over time. Therefore, unfamiliarity might also be responsible for invoking the disgust response among consumers

[29].

Among the last few barriers, anxiety related to the economic environment was also visible regarding farming and rural communities associated with conventional meat production in Ireland. Another form of economic anxiety was purchasing power relating to CUME, and its affordability for higher economic households. This anxiety could be addressed by characterizing CUME as a new opportunity to redirect agricultural stakeholders. However, further research will be needed to identify sustainable sources of settlement for these stakeholders. Moreover, the lack of data makes it unclear if redirecting stakeholders would enhance purchasing attitudes in real markets

[17].

Many experimental studies demonstrated the successful acceptance of new interventions

[19][27][30]. Ref.

[32] declared the positive contribution of additional information provided for consumer awareness. Its impact was significantly higher among urban consumers in China. Similarly, additional information also enhanced willingness to buy in Mancini and Antoniolis’ research

[24]. Ref.

[36] also concluded that providing additional information about personal benefits, remarkably, enhanced the acceptance of CUME as compared to societal benefits, meat quality, and safety

[36].

While marketing strategies are being incorporated, nomenclature and terminologies should be precisely nominated as per the aforementioned consumer attitude. For instance, the term clean meat elicited a higher consumer acceptance rate than the term lab-grown meat, and scored in the middle for other terms, including CUME and animal-free meat

[37]. Nomenclature should link positive associations with contexts. Another attribute among marketing strategies revolves around the effects of foreign language, which makes consumer behavior more utilitarian. This phenomenon was observed in a group of German participants that read about CUME in English

[38]. It invoked less disgust and a higher willingness to try, as compared to when it was briefed in their native language. Another marketing strategy could involve improving images employed to represent CUME. Instead of lab coats and test tubes, frames having similarities to conventional products should be employed. Framing the product in close accordance with existing marketed products will positively impact CUME products

[11].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app12178795