Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The azanucleosides decitabine and azacytidine are used widely in the treatment of myeloid neoplasia and increasingly in the context of combination therapies. Although they are both classed as hypomethylating agents, their modes of actions differ. Decitabine reduces DNA methylation generally, while azacytidine reduces RNA methylation at a specific subset of sites. The hypomethylating agents have overlapping, but distinct effects on neoplastic cells that are likely to have consequences for their clincal use, particularly in the context of combination therapies.

- hypomethylating agents

- decitabine

- azacytidine

- epigenetics

- myeloid leukemia

1. DNA Methylation and the DNA Methyltransferases

DNA methylation is an evolutionarily ancient process, with DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) homologues being present throughout the animal, plant and fungal kingdoms and traceable all the way back to prokaryotes [1]. DNMTs target cytosine in the context of the dinucleotide palindrome 5′-CpG-3′, resulting in methylation of the C residues on both strands of double-stranded DNA. Targeting a palindrome in this way ensures retention of the methylation mark on one strand of each duplex following replication, thus making CpG methylation marks heritable through cell division. Indeed, the enzyme DNMT1 is dedicated purely to restoring the second methyl group at such hemi-methylated sites, while DNMT3A and 3B are responsible for de novo methylation of previously non-methylated sequences.

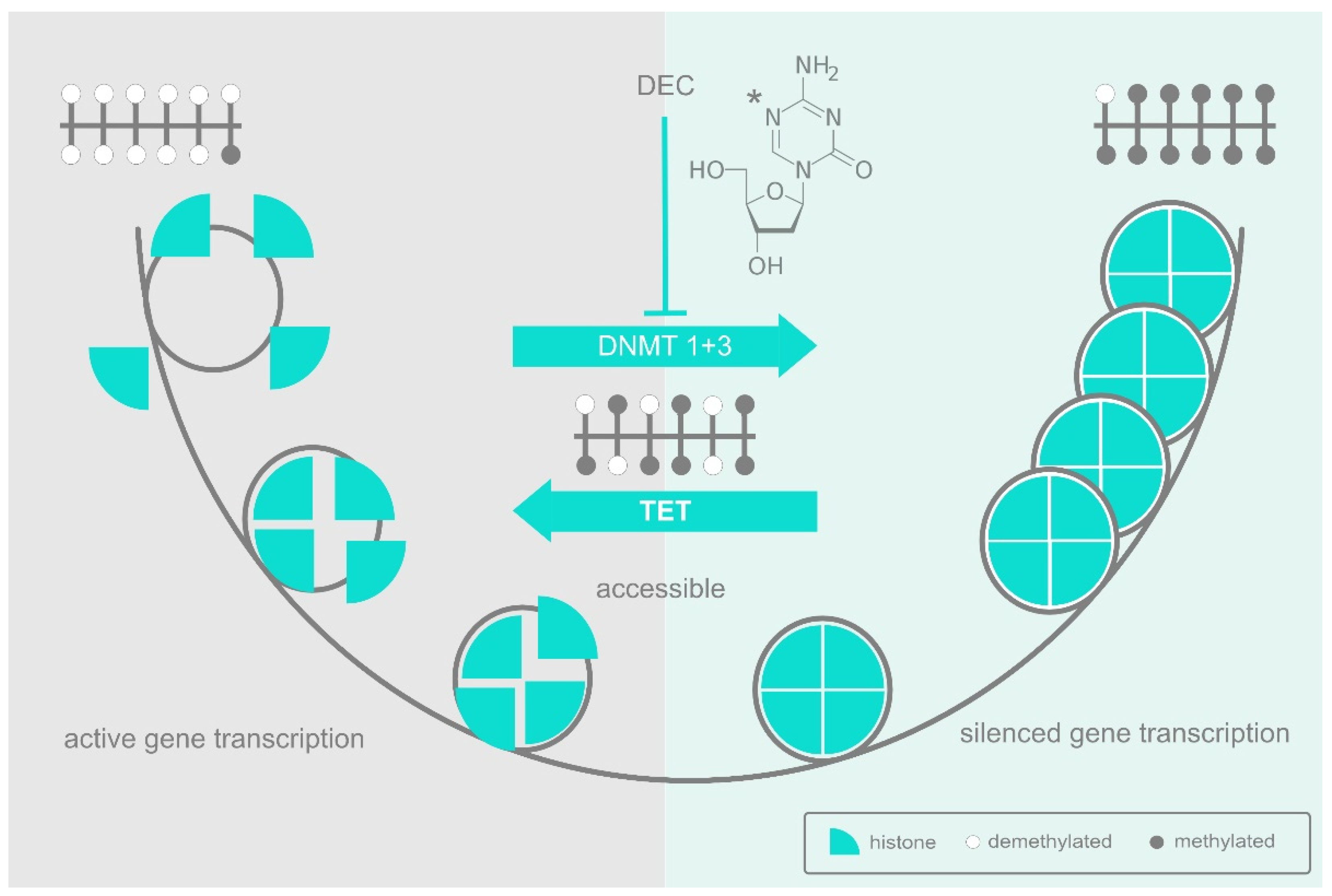

In eukaryotes, methylation of CpGs is generally associated with a reduction in the expression of associated genes, initially because methylation blocks DNA binding by sequence-specific transcription factors, and subsequently because extensively methylated DNA tends to be packaged into inaccessible chromatin structures (Figure 1). The advantages of partitioning chromatin in this way most probably have to do with the challenges of managing large, complex genomes, particularly in multicellular organisms. The packaging of large parts of the genetic repertoire into structures that are inaccessible for the transcription machinery allows resources to be focused exclusively on the subset of genes that are relevant to a given situation or cell type and avoids interference by those that are irrelevant or potentially disruptive. The lineage commitment and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells provides a good example of this. Here, multipotent stem and progenitor cells maintain genes relevant to their various multiple lineage fates in an accessible but repressed state of priming. Lineage commitment therefore involves not just as the upregulation of those genes relevant to the chosen fate, but also the inactivation of those that are relevant to all other fates and could therefore interfere [2][3][4]. DNA methylation plays a major role in this reorganisation.

The special role of CpGs as targets of methylation makes them potentially disruptive when in the wrong place, partly because of the suppressive effect of methylation itself, and partly because 5-methylcytosine (5meC) can deaminate to thymidine, thus making the DNA prone to point mutation [5]. Accordingly, evolution has selected against CpGs in most of our genome, leaving isolated groups known as “CpG islands” [6] only where they have a useful role to play in influencing gene expression. Within a CpG island, transcription factors can be recruited to their non-methylated binding sites where they act in conjunction with a range of histone-modifying enzymes to establish an open and active chromatin structure (Figure 1). However, should the relevant transcription factors be depleted, the CpGs in their respective binding sites are left unprotected and susceptible to progressive methylation that then obstructs reactivation. Even so, methylation does not lead unavoidably to a downhill spiral of suppression, since a CpG island typically consists of multiple, interacting sites, and DNA methylation by the DNMTs can be counteracted by demethylation driven by enzymes of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of methylcytosine dioxygenases. It is, therefore, the dynamic balance between DNMT-driven methylation and TET-driven demethylation that mediates dynamic reorganisation one way or the other (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Azanucleosides affect DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility. A CpG island is shown at the top left of the figure in the predominantly non-methylated state (open circles) associated with active genes. Transcription factors can access their binding sites and modify histones to loosen histone/DNA interactions and open up the chromatin for transcription. In contrast, the CpG island at the top right is fully methylated (filled circles), preventing the binding of activating transcription factors. Tightly bound histones organise the DNA into nucleosomes and subsequently into higher order heterochromatin, locking in the inactive state. The CpG Island in the centre is in a dynamic, semi-methylated state subject to further methylation by DNMT enzymes or to demethylation by TET. Decitabine (DEC), shown top centre with the C5 position of the pyrimidine ring marked (*), depletes DNMT enzymes and tips the balance towards demethylation.

Since CpG methylation patterns are transmitted through rounds of DNA replication, they allow regulatory regions that control gene expression to be either maintained in an open, active state, or marked for closure in a way that is heritable through cell division. This provides a mechanism for the inheritance of phenotype that accompanies the inheritance of genotype from mother cell to daughter cell.

2. Neoplastic Transformation

Neoplasia develops as a result of mutations in stem cells capable of self-renewal. In the condition known as "clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential" (CHIP), mutations in genes that control DNA methylation affect the epigenetic coordination of hematopoietic stem cell commitment and are likely to prepare the ground for neoplastic progression firstly by increasing mutation rate (for instance by affecting the DNA damage response) and secondly by expanding the pool of cells that have not completed commitment and are therefore still potentially capable of self-renewal. This “reflux” self-renewal loop differs from that of normal stem cells in that it is predicted to include a stage of relatively high activity. This extra active state would effectively expand the repertoire of target genes for mutations that can bestow a further selective advantage. In this way, the reduced stringency of gene regulation and expanded progenitor pool in a CHIP clone would be expected to increase the chances of further genetic/epigenetic changes that reinforce the "reflux" type self-renewal and/or establish a further self-renewal loop, for instance by blocking differentiationat the progenitor level. Each of these events leads to a further selective advantage for the affected clone.

In this model, while mutations in epigenetic regulators such as DNMT3A or TET2 can provide a basis for neoplasia, the truly transforming mutations that subsequently uncouple proliferation from differentiation target a wide range of other genes. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that all of these ultimately exert their transforming effects by interfering with the normal networks of hematopoietic gene regulation, effectively rewiring the epigenetic network to create novel states in which aberrant self-renewal can take place. Epigenetic reprogramming is, therefore, a common property of all leukemias, and not just those that carry epigenetic mutations. Since these novel epigenetic states are likely to be less stable than those that have been embedded or "canalised" by evolutionary selection, they may be more susceptible to disruption by treatment with hypomethylating agents. The benefits of HMA treatment may therefore result from a "shake-up" of unstable epigenetic networks that gives deviant cells a chance to settle back into a more stable and less neoplastic state. The "aza sahake-up" model would explain the broad efficacy of hypomethylating agents in myeloid neoplasias, including those lacking mutations in epigenetic regulators such as TET2 or DNMT3A.

3. DNMT2 and RNA Methylation

DNMT2 belongs to the same enzyme family as DNMT1 and DNMT3, but methylates cytosine residues in RNA rather than those in DNA. DNMT2 is therefore the major target of inhibition by Vidaza (which is incorpoated primarily into RNA), while DNMTs1 and 3 are inhibitied by decitabine (which is incorporated exclusivel into DNA).

Cytosine C5 methylation is just one of a wide range of modifications that can be made to RNA [7]. Furthermore, there is an entire family of enzymes that, like DNMT2, direct cytosine C5 methylation [8], meaning that DNMT2 is responsible for only a fraction of the total 5meC in RNA. Nonetheless, the high conservation of DNMT2 across species argues for an important role in cell biology. Given this, it was initially surprising that mutation of the dnmt2 gene had no obvious effect in a range of model organisms under laboratory conditions [9]. However, subsequent studies have suggested that Dnmt2 does indeed have important functions under stress conditions that are probably more relevant for evolutionary selection in the wild than for survival and reproduction in a controlled laboratory environment [10]. Eventually, a thorough re-examination of dnmt2 knock-out mice backcrossed to homogeneity into a C57BL/6 background showed that, while adult mice are normal and fertile, there is a significant delay in osteo-hematopoietic development during the immediate post-natal period [11]. This is encouraging, since the requirement for Dnmt2 in an expanding postnatal osteohematopoietic system in mice would be consistent with specific effects of DNMT2 inhibition in human leukemia. Further research has now implicated both messenger RNA (mRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA) targets of DNMT2 in the regulation of hematopoiesis [11][12][13].

4. DNMT2 Methylation of mRNA

The relevance of specific mRNA targets of DNMT2 has emerged following the independent identification of Dnmt2 among a set of RNA binding proteins that affect the lineage commitment of hematopoietic progenitors in mice [12]. By tracing a series of interactions involving both RNA- and DNA-binding proteins, Cheng et al., found that Dnmt2 methylates the freshly transcribed (nascent) 5′ end of certain mRNAs involved in hematopoietic lineage commitment. This methylation precipitates the formation of an mRNA/protein/DNA chromatin complex over the promoter region that then drives further transcription initiation. In this way, the Dnmt2-dependent complex sets up a positive feedback loop, fixing the active transcription of a key regulator once it has reached a set threshold and thus preventing the cell from going back on a decision once taken. Positive feedback loops of this sort clearly have the potential to resolve binary fate decisions quickly and cleanly by tipping them one way or the other and it is easy to see how they could help resolve lineage commitment decisions by mediating the rapid and decisive switching of gene expression as described above in the context of DNA methylation. Indeed, the Dnmt2-initated chromatin complexes described by Cheng et al. were also found to be associated with Dnmt1 and Tet2 proteins, suggesting possible co-regulation of chromatin accessibility (via DNA methylation) and transcription initiation (via RNA methylation).

5. DNMT2 Methylation of tRNA

While Dnmt2-mediated methylation of mRNA clearly has a role to play in lineage commitment, the evolutionary roots of the enzyme go much deeper: From single celled organisms up to humans, Dnmt2 directs the C5 methylation of a small number of tRNAs (primarily tRNA-Asp) at position C38 in the anticodon loop, suggesting that DNMT2 plays an important role in the control of protein translation. In support of this, a recent shRNA screen for genes required to maintain cell survival in the presence of AZA found that down-regulation of the histone acetyl transferase CBP (CREB Binding Protein) had a substantial impact on protein translation and acted synergistically with AZA to reduce cell viability, but showed no synergy with DEC [13].

The effects of C38-methylation of tRNA-Asp include an increased rate of tRNA/amino acid charging by aspartyl tRNA synthetase [14], increased tRNA stability [10] and an improved fidelity of anticodon/codon interaction that serves to minimise mistranslation of glutamate codons to aspartate and vice-versa [11]. Given that the effects of all these changes on translation would be expected to be positive, it is interesting that methylation is not constitutive. This suggests that non-methylated tRNA-Asp has a role to play under certain conditions and that Dnmt2 mediates an adaptive response.

Consistent with this, early work on fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) found that Dnmt2 (Pmt1) failed to methylate tRNA-Asp efficiently in standard growth media, but did so when the yeast was grown in medium containing peptone as a major carbon source [15]. A link between Dnmt2 activity and nutrient availability would be consistent with the retardation of post-natal osteohematopoietic development found in dnmt2−/− mice noted above [11], since this is a period of extreme proliferative activity in the establishing marrow in which an appropriate response to nutrient supply may be decisive. A requirement for Dnmt2 under stress conditions has also been described in Drosophila, in which the Dnmt2-mediated protection of tRNA sub-fragments from degradation is required for subsequent Dicer activity and an appropriate siRNA response [16].

There is, therefore, accumulating evidence that the evolutionarily ancient, DNMT2-dependent C38 methylation of tRNA-Asp is a central component of a highly conserved translational response to stress. The three direct consequences of C38 methylation for the tRNA-Asp: increased stability, more efficient aspartate loading and a higher fidelity of codon recognition, would all serve to ensure that methylated tRNA takes over rapidly from non-methylated tRNA at the ribosome following DNMT2 activation. The effects that this then has on the spectrum of protein translation are not yet well understood. However, it has been reported that null mutation of dnmt2 in mouse fibroblasts results in a strong reduction in the translation of proteins containing poly aspartate runs and that these proteins tend to be involved in transcription and gene expression [14]. This is consistent with a role for Dnmt2 in biasing translation of functional subsets of proteins in response to a change in conditions. Whether Dnmt2-dependent translation is influenced simply by the incidence of aspartate codons, or whether there may be a differential effect on the two alternative aspartate codons (GAU and GAC) is still unclear [17]. The GAU and GAC codons are indeed used differentially in genes involved in divergent cell processes such as proliferation and differentiation [18] and the Dnmt2-mediated methylation at C38 is dependent on modification of the “wobble” base 34 that can differentially affect GAU vs GUC codon recognition [19]. Even so, there is as yet no direct evidence that Dnmt2 activity can affect the relative translation efficiency of GAU vs GAC. Whatever the mechanism, there is an emerging consensus that tRNA modification by Dnmt2 exerts a level of translational control which enables the cell to cope with stress conditions. It remains to be seen whether or not the stress conditions concerned are relevant to the action of AZA in a neoplastic bone marrow environment.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11162589

References

- Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A. On the evolutionary origin of eukaryotic DNA methyltransferases and Dnmt2. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28104.

- Cross, M.A.; Enver, T. The lineage commitment of haemopoietic progenitor cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997, 7, 609–613.

- Akashi, K.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Iwasaki, H.; Niu, C.; Steenhard, B.; Zhang, J.; Haug, J.; Li, L. Transcriptional accessibility for genes of multiple tissues and hematopoietic lineages is hierarchically controlled during early hematopoiesis. Blood 2003, 101, 383–389.

- Martin, E.W.; Krietsch, J.; Reggiardo, R.E.; Sousae, R.; Kim, D.H.; Forsberg, E.C. Chromatin accessibility maps provide evidence of multilineage gene priming in hematopoietic stem cells. Epigenet. Chromatin 2021, 14, 2.

- Holliday, R.; Grigg, G.W. DNA methylation and mutation. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagenesis 1993, 285, 61–67.

- Deaton, A.M.; Bird, A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1010–1022.

- Suzuki, T. The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 375–392.

- Bohnsack, K.E.; Höbartner, C.; Bohnsack, M.T. Eukaryotic 5-methylcytosine (m⁵C) RNA Methyltransferases: Mechanisms, Cellular Functions, and Links to Disease. Genes 2019, 10, 102.

- Goll, M.G.; Kirpekar, F.; Maggert, K.A.; Yoder, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Zhang, X.; Golic, K.G.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Bestor, T.H. Methylation of tRNAAsp by the DNA methyltransferase homolog Dnmt2. Science 2006, 311, 395–398.

- Schaefer, M.; Pollex, T.; Hanna, K.; Tuorto, F.; Meusburger, M.; Helm, M.; Lyko, F. RNA methylation by Dnmt2 protects transfer RNAs against stress-induced cleavage. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1590–1595.

- Tuorto, F.; Herbst, F.; Alerasool, N.; Bender, S.; Popp, O.; Federico, G.; Reitter, S.; Liebers, R.; Stoecklin, G.; Gröne, H.-J.; et al. The tRNA methyltransferase Dnmt2 is required for accurate polypeptide synthesis during haematopoiesis. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2350–2362.

- Cheng, J.X.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Cloe, A.; Yue, M.; Wei, J.; Watanabe, K.A.; Shammo, J.M.; Anastasi, J.; Shen, Q.J.; et al. RNA cytosine methylation and methyltransferases mediate chromatin organization and 5-azacytidine response and resistance in leukaemia. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1163.

- Diesch, J.; Le Pannérer, M.-M.; Winkler, R.; Casquero, R.; Muhar, M.; van der Garde, M.; Maher, M.; Herráez, C.M.; Bech-Serra, J.J.; Fellner, M.; et al. Inhibition of CBP synergizes with the RNA-dependent mechanisms of Azacitidine by limiting protein synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6060.

- Shanmugam, R.; Fierer, J.; Kaiser, S.; Helm, M.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A. Cytosine methylation of tRNA-Asp by DNMT2 has a role in translation of proteins containing poly-Asp sequences. Cell Discov. 2015, 1, 15010.

- Becker, M.; Müller, S.; Nellen, W.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A.; Ehrenhofer-Murray, A.E. Pmt1, a Dnmt2 homolog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, mediates tRNA methylation in response to nutrient signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11648–11658.

- Durdevic, Z.; Mobin, M.B.; Hanna, K.; Lyko, F.; Schaefer, M. The RNA methyltransferase Dnmt2 is required for efficient Dicer-2-dependent siRNA pathway activity in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 931–937.

- Ehrenhofer-Murray, A.E. Cross-Talk between Dnmt2-Dependent tRNA Methylation and Queuosine Modification. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 14.

- Gingold, H.; Tehler, D.; Christoffersen, N.R.; Nielsen, M.M.; Asmar, F.; Kooistra, S.M.; Christophersen, N.S.; Christensen, L.L.; Borre, M.; Sørensen, K.D.; et al. A dual program for translation regulation in cellular proliferation and differentiation. Cell 2014, 158, 1281–1292.

- Meier, F.; Suter, B.; Grosjean, H.; Keith, G.; Kubli, E. Queuosine modification of the wobble base in tRNAHis influences ‘in vivo’ decoding properties. EMBO J. 1985, 4, 823–827.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!