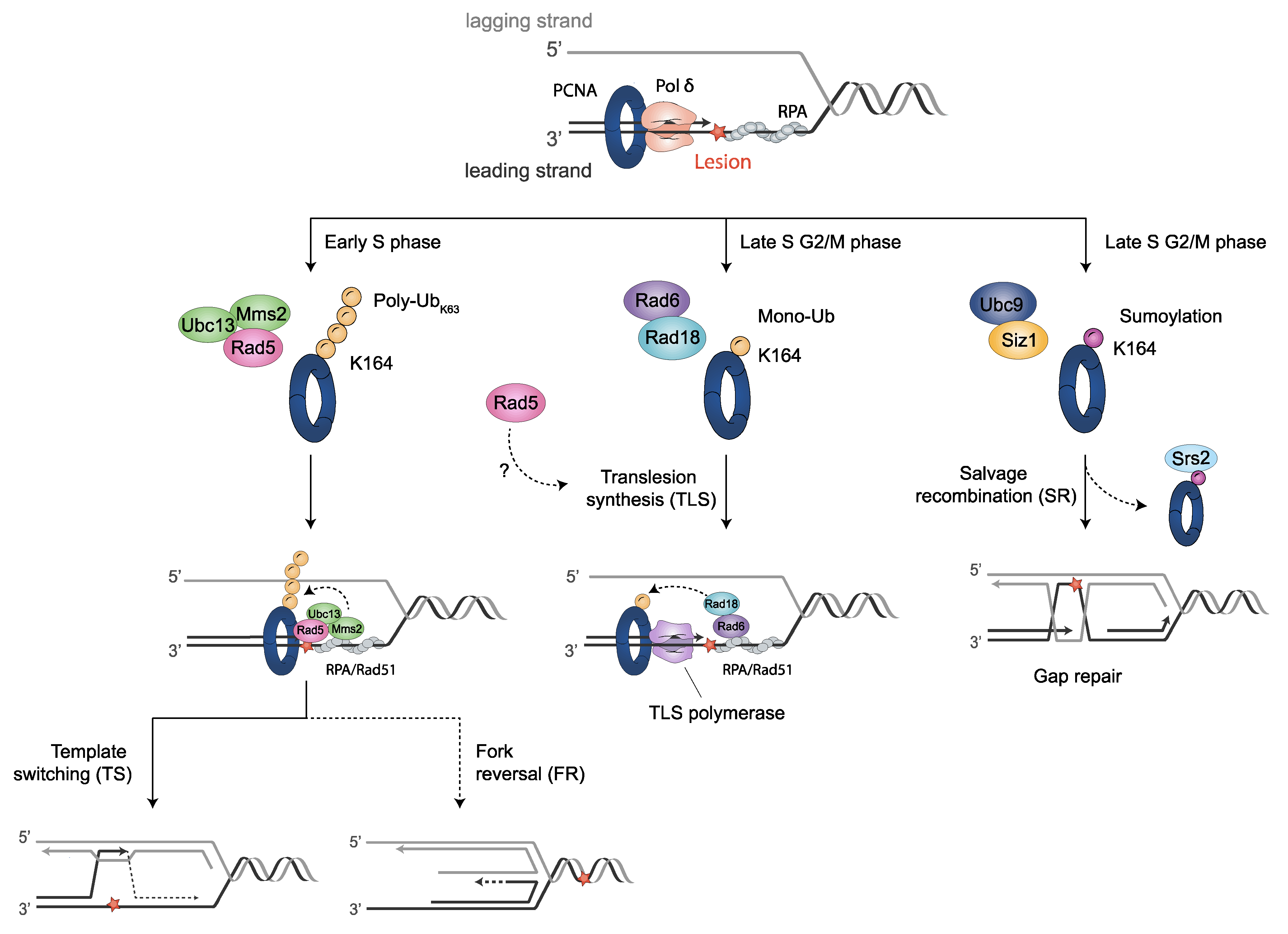

The sliding clamp proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) is a multifunctional homotrimer mainly linked to DNA replication. During this process, cells must ensure an accurate and complete genome replication when constantly challenged by the presence of DNA lesions. Post-translational modifications of PCNA play a crucial role in channeling DNA damage tolerance (DDT) and repair mechanisms to bypass unrepaired lesions and promote optimal fork replication restart. PCNA ubiquitination processes trigger the following two main DDT sub-pathways: Rad6/Rad18-dependent PCNA monoubiquitination and Ubc13-Mms2/Rad5-mediated PCNA polyubiquitination, promoting error-prone translation synthesis (TLS) or error-free template switch (TS) pathways, respectively. However, the fork protection mechanism leading to TS during fork reversal is still poorly understood. In contrast, PCNA sumoylation impedes the homologous recombination (HR)-mediated salvage recombination (SR) repair pathway.

- PCNA

- DNA damage tolerance

- DNA replication stress

- fungal genome stability

1. Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA)

2. PCNA Structural Features

3. Post-Translational Modifications of PCNA and the DDT Pathways

3.1. Translesion Synthesis (TLS)-Mediated DDT Error-Prone Pathway

3.1.1. TLS Polymerases Structural Features

3.1.2. Monoubiquitin-PCNA Modification Mediated by Rad6-Rad18

3.1.3. DNA Polymerase Switching during TLS

3.2. Rad5-Mediated Error-Free DDT Bypass Pathway

3.2.1. Polyubiquitinated PCNA by Rad5- Error-Free Pathway

3.2.2. Structural Features of Rad5, Interactions and Associated Activities

3.2.3. Template Switch (TS) Model

3.2.4. Fork Reversal Model

3.3. Alternative Ubiquitination Sites in PCNA

3.4. PCNA Sumoylation: Regulation of Homologous Recombination (HR)

3.4.1. Srs2 Helicase Negatively Regulates the HR Pathway

3.4.2. PCNA Sumoylation by Ubc9-Siz1

3.4.3. Salvage Recombination (SR) Pathway

3.5. PCNA Inner Surface Acetylation in Response to DNA Damage

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jof8060621

References

- Bauer, G.A.; Burgers, M.J. Molecular cloning, structure and expression of the yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 261–265.

- Waga, S.; Stillman, B. The DNA replication fork in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 721–751.

- Moldovan, G.L.; Pfander, B.; Jentsch, S. PCNA, the Maestro of the Replication Fork. Cell 2007, 129, 665–679.

- Henderson, D.S.; Banga, S.S.; Grigliatti, T.A.; Boyd, J.B. Mutagen sensitivity and suppression of position-effect variegation result from mutations in mus209, the Drosophila gene encoding PCNA. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 1450–1459.

- Nomura, A. Nuclear distribution of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in fertilized eggs of the starfish Asterina pectinifera. J. Cell Sci. 1994, 107, 3291–3300.

- Poot, R.A.; Bozhenok, L.; van den Berg, D.L.C.; Steffensen, S.; Ferreira, F.; Grimaldi, M.; Gilbert, N.; Ferreira, J.; Varga-Weisz, P.D. The Williams syndrome transcription factor interacts with PCNA to target chromatic remodelling by ISWI to replication foci. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 1236–1244.

- Moldovan, G.L.; Pfander, B.; Jentsch, S. PCNA Controls Establishment of Sister Chromatid Cohesion during S Phase. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 723–732.

- Liu, H.W.; Bouchoux, C.; Panarotto, M.; Kakui, Y.; Patel, H.; Uhlmann, F. Division of Labor between PCNA Loaders in DNA Replication and Sister Chromatid Cohesion Establishment. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 725–738.e4.

- Zuilkoski, C.M.; Skibbens, R.V. PCNA promotes context-specific sister chromatid cohesion establishment separate from that of chromatin condensation. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 2436–2450.

- Maga, G.; Villani, G.; Tillement, V.; Stucki, M.; Locatelli, G.A.; Frouin, I.; Spadari, S.; Hübscher, U. Okazaki fragment processing: Modulation of the strand displacement activity of DNA polymerase δ by the concerted action of replication protein A, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and flap endonuclease-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14298–14303.

- Sporbert, A.; Domaing, P.; Leonhardt, H.; Cardoso, M.C. PCNA acts as a stationary loading platform for transiently interacting Okazaki fragment maturation proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 3521–3528.

- Wyse, B.; Oshidari, R.; Rowlands, H.; Abbasi, S.; Yankulov, K. RRM3 regulates epigenetic conversions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in conjunction with Chromatin Assembly Factor I. Nucleus 2016, 7, 405–414.

- Hervouet, E.; Peixoto, P.; Delage-Mourroux, R.; Boyer-Guittaut, M.; Cartron, P.F. Specific or not specific recruitment of DNMTs for DNA methylation, an epigenetic dilemma. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 17.

- Zhang, Z.; Shibahara, K.I.; Stillman, B. PCNA connects DNA replication to epigenetic inheritance in yeast. Nature 2000, 408, 221–225.

- Ehrenhofer-Murray, A.E.; Kamakaka, R.T.; Rine, J. A role for the replication proteins PCNA, RF-C, polymerase ε and Cdc45 in transcriptional silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1999, 153, 1171–1182.

- Iida, T.; Suetake, I.; Tajima, S.; Morioka, H.; Ohta, S.; Obuse, C.; Tsurimoto, T. PCNA clamp facilitates action of DNA cytosine methyltransferase 1 on hemimethylated DNA. Genes Cells 2002, 7, 997–1007.

- Tournier, S.; Leroy, D.; Goubin, F.; Ducommun, B.; Hyams, J.S. Heterologous expression of the human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21Cip1 in the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe reveals a role for PCNA in the chk1+ cell cycle checkpoint pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 1996, 7, 651–662.

- Miyachi, K.; Fritzler, M.J.; Tan, E.M. Autoantibody to a nuclear antigen in proliferating cells. J. Immunol. 1978, 121, 2228–2234.

- Bravo, R.; Fey, S.J.; Bellatin, J.; Larsen, P.M.; Celis, J.E. Identification of a nuclear polypeptide (“cyclin”) whose relative proportion is sensitive to changes in the rate of cell proliferation and to transformation. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1982, 85, 235–248.

- Mathews, M.B.; Bernstein, R.M.; Franza, B.R.; Garrels, J.I. Identity of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen and cyclin. Nature 1984, 309, 374–376.

- Tan, C.-K.; Castillo, C.; So, A.G.; Downey, K.M. An auxiliary protein for DNA polymerase-δ from fetal calf thymus. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 12310–12316.

- Prelich, G.; Tan, C.K.; Kostura, M.; Mathews, M.B.; So, A.G.; Downey, K.M.; Stillman, B. Functional identity of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and a DNA polymerase-δ auxiliary protein. Nature 1987, 326, 517–520.

- Bravo, R.; Frank, R.; Blundell, P.A.; Macdonald-Bravo, H. Cyclin/PCNA is the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase-δ. Nature 1987, 326, 515–517.

- Fairman, M.; Prelich, G.; Tsurimoto, T.; Stillman, B. Identification of cellular components required for SV40 DNA replication in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1988, 905, 382–387.

- Yoder, B.L.; Burgers, P.M.J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication factor C. I. Purification and characterization of its ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 22689–22697.

- Lee, S.H.; Pan, Z.Q.; Kwong, A.D.; Burgers, P.M.; Hurwitz, J. Synthesis of DNA by DNA polymerase epsilon in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 22707–22717.

- Bravo, R.; Macdonald-Bravo, H. Existence of two populations of cyclin/proliferating cell nuclear antigen during the cell cycle: Association with DNA replication sites. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 1549–1554.

- Prelich, G.; Stillman, B. Coordinated leading and lagging strand synthesis during SV40 DNA replication in vitro requires PCNA. Cell 1988, 53, 117–126.

- Celis, J.E.; Madsen, P. Increased nuclear cyclin/PCNA antigen staining of non S-phase transformed human amnion cells engaged in nucleotide excision DNA repair. FEBS Lett. 1986, 209, 277–283.

- Toschi, L.; Bravo, R. Changes in cyclin/proliferating cell nuclear antigen distribution during DNA repair synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 1623–1628.

- Dresler, S.L.; Kimbro, K.S. 2’, 3’-Dideoxy thymidine 5’-Triphosphate Inhibition of DNA Replication and Ultraviolet-Induced DNA Repair Synthesis in Human Cells: Evidence for Involvement of DNA Polymerase δ. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 2664–2668.

- Nishida, C.; Reinhard, P.; Linn, S. DNA repair synthesis in human fibroblasts requires DNA plymerase δ. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 501–510.

- Shivji, M.K.K.; Kenny, M.K.; Wood, R.D. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is required for DNA excision repair. Cell 1992, 69, 367–374.

- Nichols, A.F.; Sancar, A. Purification of PCNA as a nucleotide excision repair protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 2441–2446.

- Li, R.; Waga, S.; Hannon, G.J.; Beach, D.; Stillman, B. Differential effects by the p21 CDK inhibitor on PCNA-dependent DNA replication and repair. Nature 1994, 371, 534–537.

- Umar, A.; Buermeyer, A.B.; Simon, J.A.; Thomas, D.C.; Clark, A.B.; Liskay, R.M.; Kunkel, T.A. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA resynthesis. Cell 1996, 87, 65–73.

- Johnson, R.E.; Kovvali, G.K.; Guzder, S.N.; Amin, N.S.; Holm, C.; Habraken, Y.; Sung, P.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S. Evidence for involvement of yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen in DNA mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 27987–27990.

- Lau, P.J.; Kolodner, R.D. Transfer of the MSH2·MSH6 complex from proliferating cell nuclear antigen to mispaired bases in DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14–17.

- Klungland, A.; Lindahl, T. Second pathway for completion of human DNA base excision-repair: Reconstitution with purified proteins and requirement for DNase IV (FEN1). EMBO J. 1997, 16, 3341–3348.

- Gary, R.; Kim, K.; Cornelius, H.L.; Park, M.S.; Matsumoto, Y. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen facilitates excision in long-patch base excision repair. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 4354–4363.

- Levin, D.S.; McKenna, A.E.; Motycka, T.A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Tomkinson, A.E. Interaction between PCNA and DNA ligase I is critical for joining of Okazaki fragments and long-patch base-excision repair. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 919–922.

- Matsumoto, Y. Molecular mechanism of PCNA-dependent base excision repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001, 68, 129–138.

- Lebel, M.; Spillare, E.A.; Harris, C.C.; Leder, P. The Werner syndrome gene product co-purifies with the DNA replication complex and interacts with PCNA and topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 37795–37799.

- Kamath-Loeb, A.S.; Johansson, E.; Burgers, P.M.J.; Loeb, L.A. Functional interaction between the Werner syndrome protein and DNA polymerase δ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4603–4608.

- Liberti, S.E.; Andersen, S.D.; Wang, J.; May, A.; Miron, S.; Perderiset, M.; Keijzers, G.; Nielsen, F.C.; Charbonnier, J.B.; Bohr, V.A.; et al. Bi-directional routing of DNA mismatch repair protein human exonuclease 1 to replication foci and DNA double strand breaks. DNA Repair 2011, 10, 73–86.

- Haracska, L.; Johnson, R.E.; Unk, I.; Phillips, B.; Hurwitz, J.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S. Physical and Functional Interactions of Human DNA Polymerase η with PCNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 7199–7206.

- Haracska, L.; Johnson, R.E.; Unk, I.; Phillips, B.B.; Hurwitz, J.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S. Targeting of human DNA polymerase ι to the replication machinery via interaction with PCNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14256–14261.

- Haracska, L.; Unk, I.; Johnson, R.E.; Phillips, B.B.; Hurwitz, J.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S. Stimulation of DNA Synthesis Activity of Human DNA Polymerase κ by PCNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 784–791.

- Kannouche, P.; Fernández de Henestrosa, A.R.; Coull, B.; Vidal, A.E.; Gray, C.; Zicha, D.; Woodgate, R.; Lehmann, A.R. Localization of DNA polymerases eta and iota to the replication machinery is tightly co-ordinated in human cells. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1223–1233.

- Maga, G.; Villani, G.; Ramadan, K.; Shevelev, I.; Le Gac, N.T.; Blanco, L.; Blanca, G.; Spadari, S.; Hübscher, U. Human DNA polymerase λ functionally and physically interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen in normal and translesion DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 48434–48440.

- Li, M.; Xu, X.; Chang, C.W.; Liu, Y. TRIM28 functions as the SUMO E3 ligase for PCNA in prevention of transcription induced DNA breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 23588–23596.

- Daigaku, Y.; Davies, A.A.; Ulrich, H.D. Ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is separable from genome replication. Nature 2010, 465, 951–955.

- Krishna, T.S.R.; Kong, X.P.; Gary, S.; Burgers, P.M.; Kuriyan, J. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA. Cell 1994, 79, 1233–1243.

- Kelman, Z.; O’donnell, M. Structural and functional similarities of prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA polymerase sliding clamps. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 3613–3620.

- Fukuda, K.; Morioka, H.; Imajou, S.; Ikeda, S.; Ohtsuka, E.; Tsurimoto, T. Structure-function relationship of the eukaryotic DNA replication factor, proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 22527–22534.

- Kondratick, C.M.; Litman, J.M.; Shaffer, K.V.; Washington, M.T.; Dieckman, L.M. Crystal structures of PCNA mutant proteins defective in gene silencing suggest a novel interaction site on the front face of the PCNA ring. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193333.

- Kochaniak, A.B.; Habuchi, S.; Loparo, J.J.; Chang, D.J.; Cimprich, K.A.; Walter, J.C.; van Oijen, A.M. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen uses two distinct modes to move along DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17700–17710.

- De March, M.; Merino, N.; Barrera-Vilarmau, S.; Crehuet, R.; Onesti, S.; Blanco, F.J.; De Biasio, A. Structural basis of human PCNA sliding on DNA. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13935.

- Yao, N.Y.; O’Donnell, M. DNA Replication: How Does a Sliding Clamp Slide? Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R174–R176.

- Hedglin, M.; Pandey, B.; Benkovic, S.J. Stability of the human polymerase δ holoenzyme and its implications in lagging strand DNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1777–E1786.

- Zheng, F.; Georgescu, R.E.; Li, H.; O’Donnell, M.E. Structure of eukaryotic DNA polymerase δ bound to the PCNA clamp while encircling DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 30344–30353.

- Billon, P.; Côté, J. Novel mechanism of PCNA control through acetylation of its sliding surface. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2017, 4, e1279724.

- De March, M.; Barrera-Vilarmau, S.; Crespan, E.; Mentegari, E.; Merino, N.; Gonzalez-Magaña, A.; Romano-Moreno, M.; Maga, G.; Crehuet, R.; Onesti, S.; et al. P15PAF binding to PCNA modulates the DNA sliding surface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9816–9828.

- Cazzalini, O.; Sommatis, S.; Tillhon, M.; Dutto, I.; Bachi, A.; Rapp, A.; Nardo, T.; Scovassi, A.I.; Necchi, D.; Cardoso, M.C.; et al. CBP and p300 acetylate PCNA to link its degradation with nucleotide excision repair synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 8433–8448.

- Warbrick, E. The puzzle of PCNA’s many partners. BioEssays 2000, 22, 997–1006.

- Maga, G.; Hübscher, U. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): A dancer with many partners. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 3051–3060.

- Prestel, A.; Wichmann, N.; Martins, J.M.; Marabini, R.; Kassem, N.; Broendum, S.S.; Otterlei, M.; Nielsen, O.; Willemoës, M.; Ploug, M.; et al. The PCNA interaction motifs revisited: Thinking outside the PIP-box. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 4923–4943.

- Warbrick, E. PCNA binding through a conserved motif. BioEssays 1998, 20, 195–199.

- Mailand, N.; Gibbs-Seymour, I.; Bekker-Jensen, S. Regulation of PCNA-protein interactions for genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 269–282.

- Havens, C.G.; Walter, J.C. Docking of a Specialized PIP Box onto Chromatin-Bound PCNA Creates a Degron for the Ubiquitin Ligase CRL4Cdt2. Mol. Cell 2009, 35, 93–104.

- Gilljam, K.M.; Feyzi, E.; Aas, P.A.; Sousa, M.M.L.; Müller, R.; Vågbø, C.B.; Catterall, T.C.; Liabakk, N.B.; Slupphaug, G.; Drabløs, F.; et al. Identification of a novel, widespread, and functionally important PCNA-binding motif. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 645–654.

- Hishiki, A.; Hashimoto, H.; Hanafusa, T.; Kamei, K.; Ohashi, E.; Shimizu, T.; Ohmori, H.; Sato, M. Structural basis for novel interactions between human translesion synthesis polymerases and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 10552–10560.

- Lancey, C.; Tehseen, M.; Raducanu, V.S.; Rashid, F.; Merino, N.; Ragan, T.J.; Savva, C.G.; Zaher, M.S.; Shirbini, A.; Blanco, F.J.; et al. Structure of the processive human Pol δ holoenzyme. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1109.

- Sebesta, M.; Cooper, C.D.O.; Ariza, A.; Carnie, C.J.; Ahel, D. Structural insights into the function of ZRANB3 in replication stress response. Nat. Commun. 2017, 16, 15847.

- Hara, K.; Uchida, M.; Tagata, R.; Yokoyama, H.; Ishikawa, Y.; Hishiki, A.; Hashimoto, H. Structure of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) bound to an APIM peptide reveals the universality of PCNA interaction. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2018, 74, 214–221.

- Xu, H.; Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Lee, M.Y.W.T. A novel PCNA-binding motif identified by the panning of a random peptide display library. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 4512–4520.

- Liang, Z.; Diamond, M.; Smith, J.A.; Schnell, M.; Daniel, R. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is required for loading of the SMCX/KMD5C histone demethylase onto chromatin. Epigenetics Chromatin 2011, 4, 18.

- Boehm, E.M.; Washington, M.T. R.I.P. to the PIP: PCNA-binding motif no longer considered specific: PIP motifs and other related sequences are not distinct entities and can bind multiple proteins involved in genome maintenance. BioEssays 2016, 38, 1117–1122.

- Yoon, M.K.; Venkatachalam, V.; Huang, A.; Choi, B.S.; Stultz, C.M.; Chou, J.J. Residual structure within the disordered C-terminal segment of p21 Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 and its implications for molecular recognition. Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 337–347.

- Cordeiro, T.N.; Chen, P.C.; De Biasio, A.; Sibille, N.; Blanco, F.J.; Hub, J.S.; Crehuet, R.; Bernadó, P. Disentangling polydispersity in the PCNA-p15PAF complex, a disordered, transient and multivalent macromolecular assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 1501–1515.

- Click, T.H.; Ganguly, D.; Chen, J. Intrinsically disordered proteins in a physics-based world. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 5292–5309.

- Wright, P.E.; Dyson, H.J. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 11, 5292–5309.

- Prakash, S.; Johnson, R.E.; Prakash, L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: Specificity of structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 317–353.

- Lehmann, A.R.; Niimi, A.; Ogi, T.; Brown, S.; Sabbioneda, S.; Wing, J.F.; Kannouche, P.L.; Green, C.M. Translesion synthesis: Y-family polymerases and the polymerase switch. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 891–899.

- Waters, L.S.; Minesinger, B.K.; Wiltrout, M.E.; D’Souza, S.; Woodruff, R.V.; Walker, G.C. Eukaryotic Translesion Polymerases and Their Roles and Regulation in DNA Damage Tolerance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 134–154.

- Washington, M.T.; Carlson, K.D.; Freudenthal, B.D.; Pryor, J.M. Variations on a theme: Eukaryotic Y-family DNA polymerases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2010, 1804, 1113–1123.

- Boiteux, S.; Jinks-Robertson, S. DNA repair mechanisms and the bypass of DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2013, 193, 1025–1064.

- Lawrence, C.W. Cellular roles of DNA polymerase ζ and Rev1 protein. DNA Repair 2002, 1, 425–435.

- Guilliam, T.A.; Yeeles, J.T.P. Reconstitution of translesion synthesis reveals a mechanism of eukaryotic DNA replication restart. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 450–460.

- Pryor, J.M.; Gakhar, L.; Washington, M.T. Structure and Functional Analysis of the BRCT Domain of Translesion Synthesis DNA Polymerase Rev1. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 254–263.

- Hedglin, M.; Benkovic, S.J. Eukaryotic Translesion DNA Synthesis on the Leading and Lagging Strands: Unique Detours around the Same Obstacle. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7857–7877.

- Prakash, S.; Prakash, L. Translesion DNA synthesis in eukaryotes: A one- or two-polymerase affair. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1872–1883.

- Sale, J.E.; Lehmann, A.R.; Woodgate, R. Y-family DNA polymerases and their role in tolerance of cellular DNA damage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 141–152.

- Woodgate, R. A plethora of lesion-replicating DNA polymerases. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2191–2195.

- Nelson, J.; Lawrence, C.; Hinkle, D. Thymine-Thymine Dimer Bypass by Yeast DNA Polymerase ζ. Science 1996, 272, 1646–1649.

- Baranovskiy, A.G.; Lada, A.G.; Siebler, H.M.; Zhang, Y.; Pavlov, Y.I.; Tahirov, T.H. DNA polymerase δ and ζ switch by sharing accessory subunits of DNA polymerase δ. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17281–17287.

- Makarova, A.V.; Stodola, J.L.; Burgers, P.M. A four-subunit DNA polymerase ζ complex containing Pol δ accessory subunits is essential for PCNA-mediated mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11618–11626.

- Makarova, A.V.; Burgers, P.M. Eukaryotic DNA polymerase ζ. DNA Repair 2015, 29, 47–55.

- Gómez-Llorente, Y.; Malik, R.; Jain, R.; Choudhury, J.R.; Johnson, R.E.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S.; Ubarretxena-Belandia, I.; Aggarwal, A.K. The Architecture of Yeast DNA Polymerase ζ. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 79–86.

- Malik, R.; Kopylov, M.; Gomez-Llorente, Y.; Jain, R.; Johnson, R.E.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S.; Ubarretxena-Belandia, I.; Aggarwal, A.K. Structure and mechanism of B-family DNA polymerase ζ specialized for translesion DNA synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 913–924.

- McCulloch, S.; Kokoska, J.; Masutani, C.; Iwai, S.; Hanaoka, F. Preferential cis–syn thymine dimer bypass by DNA polymerase η occurs with biased fidelity. Nature 2004, 428, 97–100.

- Johnson, R.E.; Prakash, S.; Prakash, L. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Polη. Science 1999, 283, 1001–1004.

- Masutani, C.; Kusumoto, R.; Yamada, A.; Dohmae, N.; Yokoi, M.; Yuasa, M.; Araki, M.; Iwai, S.; Takio, K.; Hanaoka, F. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature 1999, 399, 700–704.

- Guo, C.; Sonoda, E.; Tang, T.S.; Parker, J.L.; Bielen, A.B.; Takeda, S.; Ulrich, H.D.; Friedberg, E.C. REV1 Protein Interacts with PCNA: Significance of the REV1 BRCT Domain In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 265–271.

- Pustovalova, Y.; MacIejewski, M.W.; Korzhnev, D.M. NMR mapping of PCNA interaction with translesion synthesis DNA polymerase Rev1 mediated by Rev1-BRCT domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 3091–3105.

- Bienko, M.; Green, C.M.; Crosetto, N.; Rudolf, F.; Zapart, G.; Coull, B.; Kannouche, P.; Wider, G.; Peter, M.; Lehmann, A.R.; et al. Biochemistry: Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science 2005, 310, 1821–1824.

- Ohashi, E.; Murakumo, Y.; Kanjo, N.; Akagi, J.I.; Masutani, C.; Hanaoka, F.; Ohmori, H. Interaction of hREV1 with three human Y-family DNA polymerases. Genes to Cells 2004, 9, 523–531.

- Ohashi, E.; Hanafusa, T.; Kamei, K.; Song, I.; Tomida, J.; Hashimoto, H.; Vaziri, C.; Ohmori, H. Identification of a novel REV1-interacting motif necessary for DNA polymerase κ function. Genes Cells 2009, 14, 101–111.

- Wojtaszek, J.; Liu, J.; D’Souza, S.; Wang, S.; Xue, Y.; Walker, G.C.; Zhou, P. Multifaceted recognition of vertebrate Rev1 by translesion polymerases ζ and κ. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 26400–26408.

- Wojtaszek, J.; Lee, C.J.; D’Souza, S.; Minesinger, B.; Kim, H.; D’Andrea, A.D.; Walker, G.C.; Zhou, P. Structural basis of rev1-mediated assembly of a quaternary vertebrate translesion polymerase complex consisting of Rev1, heterodimeric polymerase (Pol) ζ, and Pol κ. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 33836–33846.

- Hoege, C.; Pfander, B.; Moldovan, G.; Pyrowolakis, G.; Jentsch, S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 2002, 419, 135–141.

- Stelter, P.; Ulrich, H.D. Control of spontaneous and damage-induced mutagenesis by SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation. Nature 2003, 425, 188–191.

- Plosky, B.S.; Vidal, A.E.; De Henestrosa, A.R.F.; McLenigan, M.P.; McDonald, J.P.; Mead, S.; Woodgate, R. Controlling the subcellular localization of DNA polymerases ι and η via interactions with ubiquitin. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 2847–2855.

- Garg, P.; Burgers, P.M. Ubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen activates translesion DNA polymerases η and REV1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18361–18366.

- Freudenthala, B.; Brogiea, J.; Gakharb, L.; Kondraticka, C.; Washington, T. Crystal structure of SUMO-modified proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Bone 2011, 406, 9–17.

- Indiani, C.; McInerney, P.; Georgescu, R.; Goodman, M.F.; O’Donnell, M. A sliding-clamp toolbelt binds high- and low-fidelity DNA polymerases simultaneously. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 805–815.

- Kath, J.E.; Chang, S.; Scotland, M.K.; Wilbertz, J.H.; Jergic, S.; Dixon, N.E.; Sutton, M.D.; Loparo, J.J. Exchange between Escherichia coli polymerases II and III on a processivity clamp. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, 1681–1690.

- Cranford, M.T.; Chu, A.M.; Baguley, J.K.; Bauer, R.J.; Trakselis, M.A. Characterization of a coupled DNA replication and translesion synthesis polymerase supraholoenzyme from archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 8329–8340.

- Guilliam, T.A. Mechanisms for Maintaining Eukaryotic Replisome Progression in the Presence of DNA Damage. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 712971.

- Murakumo, Y.; Ogura, Y.; Ishii, H.; Numata, S.I.; Ichihara, M.; Croce, C.M.; Fishel, R.; Takahashi, M. Interactions in the Error-prone Postreplication Repair Proteins hREV1, hREV3, and hREV7. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 35644–35651.

- Zhao, L.; Todd Washington, M. Translesion synthesis: Insights into the selection and switching of DNA polymerases. Genes 2017, 8, 24.

- Haracska, L.; Washington, M.T.; Prakash, S.; Prakash, L. Inefficient Bypass of an Abasic Site by DNA Polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6861–6866.

- Ross, A.L.; Simpson, L.J.; Sale, J.E. Vertebrate DNA damage tolerance requires the C-terminus but not BRCT or transferase domains of REV1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 1280–1289.

- Edmunds, C.E.; Simpson, L.J.; Sale, J.E. PCNA Ubiquitination and REV1 Define Temporally Distinct Mechanisms for Controlling Translesion Synthesis in the Avian Cell Line DT40. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 519–529.

- Boehm, E.M.; Spies, M.; Washington, M.T. PCNA tool belts and polymerase bridges form during translesion synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 8250–8260.

- Northam, M.R.; Garg, P.; Baitin, D.M.; Burgers, P.M.J.; Shcherbakova, P.V. A novel function of DNA polymerase ζ regulated by PCNA. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4316–4325.

- Northam, M.R.; Robinson, H.A.; Kochenova, O.V.; Shcherbakova, P.V. Participation of DNA polymerase ζ in replication of undamaged DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2010, 184, 27–42.

- Becker, J.R.; Nguyen, H.D.; Wang, X.; Bielinsky, A.K. Mcm10 deficiency causes defective-replisome-induced mutagenesis and a dependency on error-free postreplicative repair. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 1737–1748.

- Denkiewicz-Kruk, M.; Jedrychowska, M.; Endo, S.; Araki, H.; Jonczyk, P.; Dmowski, M.; Fijalkowska, I.J. Recombination and pol ζ rescue defective dna replication upon impaired cmg helicase—pol ε interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9484.

- Branzei, D.; Vanoli, F.; Foiani, M. SUMOylation regulates Rad18-mediated template switch. Nature 2008, 456, 915–920.

- Giannattasio, M.; Zwicky, K.; Follonier, C.; Foiani, M.; Lopes, M.; Branzei, D. Visualization of recombination-mediated damage bypass by template switching. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 884–892.

- Brusky, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, W. UBC13, a DNA-damage-inducible gene, is a member of the error-free postreplication repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2000, 37, 168–174.

- Xiao, W.; Chow, B.L.; Fontanie, T.; Ma, L.; Bacchetti, S.; Hryciw, T.; Broomfield, S. Genetic interactions between error-prone and error-free postreplication repair pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res.—DNA Repair 1999, 435, 1–11.

- Takahashi, T.S.; Wollscheid, H.P.; Lowther, J.; Ulrich, H.D. Effects of chain length and geometry on the activation of DNA damage bypass by polyubiquitylated PCNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 3042–3052.

- Ripley, B.M.; Gildenberg, M.S.; Todd Washington, M. Control of DNA damage bypass by ubiquitylation of PCNA. Genes 2020, 11, 138.

- Chavez, D.A.; Greer, B.H.; Eichman, B.F. The HIRAN domain of helicase-like transcription factor positions the DNA translocase motor to drive efficient DNA fork regression. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8484–8494.

- Hishiki, A.; Hara, K.; Ikegaya, Y.; Yokoyama, H.; Shimizu, T.; Sato, M.; Hashimoto, H. Structure of a novel DNA-binding domain of Helicase-like Transcription Factor (HLTF) and its functional implication in DNA damage tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 13215–13223.

- Achar, Y.J.; Balogh, D.; Neculai, D.; Juhasz, S.; Morocz, M.; Gali, H.; Dhe-Paganon, S.; Venclovas, Č.; Haracska, L. Human HLTF mediates postreplication repair by its HIRAN domain-dependent replication fork remodelling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 10277–10291.

- Beyer, D.C.; Ghoneim, M.K.; Spies, M. Structure and Mechanisms of SF2 DNA Helicases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 767, 47–73.

- Ulrich, H.D.; Jentsch, S. Two RING finger proteins mediate cooperation between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes in DNA repair. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3388–3397.

- Unk, I.; Hajdú, I.; Fátyol, K.; Szakál, B.; Blastyák, A.; Bermudez, V.; Hurwitz, J.; Prakash, L.; Prakash, S.; Haracska, L. Human SHPRH is a ubiquitin ligase for Mms2-Ubc13-dependent polyubiquitylation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18107–18112.

- Broomfield, S.; Hryciw, T.; Xiao, W. DNA postreplication repair and mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. Repair 2001, 9, 167–184.

- Kondratick, C.M.; Washington, M.T.; Spies, M. Making choices: DNA replication fork recovery mechanisms. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 113, 27–37.

- Qiu, S.; Jiang, G.; Cao, L.; Huang, J. Replication Fork Reversal and Protection. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 670392.

- Sogo, J.M.; Lopes, M.; Foiani, M. Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science 2002, 297, 599–602.

- Leung, W.; Baxley, R.M.; Moldovan, G.L.; Bielinsky, A.K. Mechanisms of DNA damage tolerance: Post-translational regulation of PCNA. Genes 2019, 10, 10.

- Das-Bradoo, S.; Nguyen, H.D.; Wood, J.L.; Ricke, R.M.; Haworth, J.C.; Bielinsky, A.K. Defects in DNA ligase i trigger PCNA ubiquitylation at Lys 107. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 74–79.

- Da Nguyen, H.; Becker, J.; Thu, Y.M.; Costanzo, M.; Koch, E.N.; Smith, S.; Myung, K.; Myers, C.L.; Boone, C.; Bielinsky, A.K. Unligated Okazaki Fragments Induce PCNA Ubiquitination and a Requirement for Rad59-Dependent Replication Fork Progression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66379.

- Su, J.; Xu, R.; Mongia, P.; Toyofuku, N.; Nakagawa, T. Fission yeast Rad8/HLTF facilitates Rad52-dependent chromosomal rearrangements through PCNA lysine 107 ubiquitination. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009671.

- Pfander, B.; Moldovan, G.-L.; Sacher, M.; Hoege, C.; Jentsch, S. SUMO-modified PCNA recruits Srs2 to prevent recombination during S phase. Nature 2005, 436, 428–433.

- Xu, X.; Blackwell, S.; Lin, A.; Li, F.; Qin, Z.; Xiao, W. Error-free DNA-damage tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res.—Rev. Mutat. Res. 2015, 764, 43–50.

- Niu, H.; Klein, H.L. Multifunctional roles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Srs2 protein in replication, recombination and repair. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17, 1–9.

- Lawrence, C.W.; Christensen, R.B. Metabolic suppressors of trimethoprim and ultraviolet light sensitivities of Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad6 mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1979, 139, 866–876.

- Schiestl, R.H.; Prakash, S.; Prakash, L. The SRS2 Suppressor of rad6 Mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Acts by Channeling DNA Lesions Into the RAD52 DNA Repair Pathway. Genetics 1990, 124, 817–831.

- Chiolo, I.; Carotenuto, W.; Maffioletti, G.; Petrini, J.H.J.; Foiani, M.; Liberi, G. Srs2 and Sgs1 DNA Helicases Associate with Mre11 in Different Subcomplexes following Checkpoint Activation and CDK1-Mediated Srs2 Phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 5738–5751.

- Armstrong, A.A.; Mohideen, F.; Lima, C.D. Recognition of SUMO-modified PCNA requires tandem receptor motifs in Srs2. Nature 2012, 483, 59–65.

- Desterro, J.M.P.; Thomson, J.; Hay, R.T. Ubch9 conjugates SUMO but not ubiquitin. FEBS Lett. 1997, 417, 297–300.

- Branzei, D.; Szakal, B. DNA damage tolerance by recombination: Molecular pathways and DNA structures. DNA Repair 2016, 44, 68–75.

- Papouli, E.; Chen, S.; Davies, A.A.; Huttner, D.; Krejci, L.; Sung, P.; Ulrich, H.D. Crosstalk between SUMO and ubiquitin on PCNA is mediated by recruitment of the helicase Srs2p. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 123–133.

- Urulangodi, M.; Sebesta, M.; Menolfi, D.; Szakal, B.; Sollier, J.; Sisakova, A.; Krejci, L.; Branzei, D. Local regulation of the Srs2 helicase by the SUMO-like domain protein Esc2 promotes recombination at sites of stalled replication. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2067–2080.

- Ivanov, I.; Chapados, B.R.; McCammon, J.A.; Tainer, J.A. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen loaded onto double-stranded DNA: Dynamics, minor groove interactions and functional implications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 6023–6033.

- Billon, P.; Li, J.; Lambert, J.P.; Chen, Y.; Tremblay, V.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Gingras, A.C.; Verreault, A.; Sugiyama, T.; Couture, J.F.; et al. Acetylation of PCNA Sliding Surface by Eco1 Promotes Genome Stability through Homologous Recombination. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 78–90.