L-dopa is a precursor of dopamine used as the most effective symptomatic drug treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Most of the L-dopa isolated is either synthesized chemically or from natural sources, but only some plants belonging to the Fabaceae family contain significant amounts of L-dopa. Due to its low stability, the unambiguous determination of L-dopa in plant matrices requires appropriate technologies. Several analytical methods have been developed for the determination of L-dopa in different plants. The most used for quantification of L-dopa are mainly based on capillary electrophoresis or chromatographic methods, i.e., high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), coupled to ultraviolet-visible or mass spectrometric detection. HPLC is most often used.

- levodopa

- plant matrices

- extraction

- chromatographic methods

1. Introduction

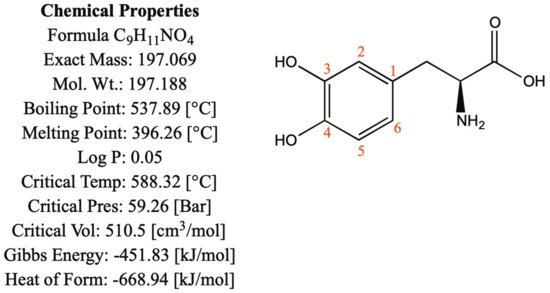

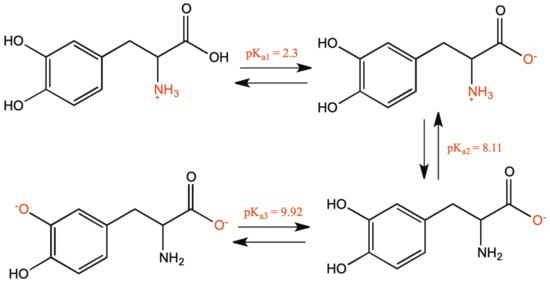

1.1. Chemical and Physical Properties

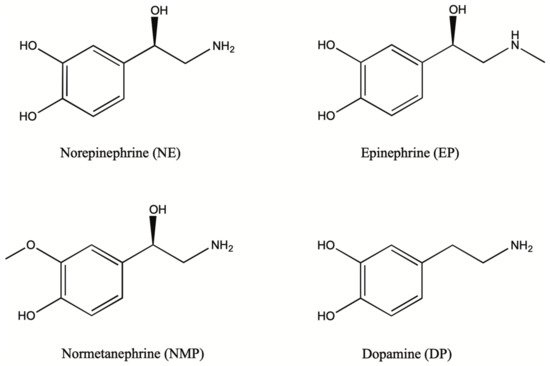

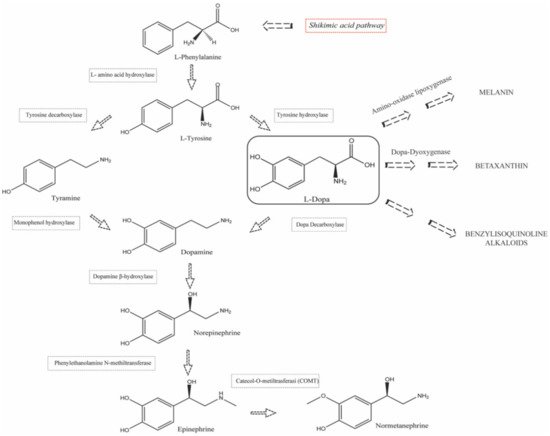

1.2. Biosynthesis and Conversion Routes of Levodopa in Plants

2. Levodopa Extraction Techniques

|

Extraction Technique |

Matrix |

Variety |

Solvents and Optimized Conditions |

Recovery Percent (Mean Value Percent) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Solid–liquid extraction (LSE) |

Mucuna pruriens dehulled and whole seed |

White and black var. utilis |

HCl 0.1 M; solvent: sample ratio 100:1 (v/w), extraction time 2 × (30 sec under homogenization and 1 h under stirring); extraction temperature 22 °C |

101.8% |

[35] |

|

Broad bean, cocoa and beans |

// |

HClO4 0.2 M, solvent: sample ratio 5:1 (v/w), extraction time 24 h under shaking time for time; extraction temperature 25 °C |

Within-day 84.4–96.0% Between-day 84.0–83.1% |

[38] |

|

|

Vicia faba seeds (cotyledons and embryo axis) |

var. Alameda var. Brocal |

HClO4 0.83 mol/kg; solvent: sample ratio 100:1 (v/w); extraction time 1 min under homogenization; extraction temperature 4 °C |

// |

[25] |

|

|

Vicia faba broad beans |

Iambola, San Francesco, FV5, Cegliese, Extra-early purple and Aguadulce supersimonia |

5% w/v HClO4 solution; solvent: sample ratio 10:1 (v/w); extraction time 5 min under homogenization; extraction temperature 4 °C |

// |

[39] |

|

|

Vicia Faba roots, sprouts and seeds |

// |

Formic acid:ethanol (1:1 v/v); solvent: sample ratio (10–40):1 (v/w); extraction time 5 × 120 min at 120 rpm; extraction temperature 4 °C |

94.1–116.6% |

[40] |

|

|

Mucuna pruriens seed cooked and raw |

// |

Water; solvent: sample ratio 400:1 (v/w); extraction time 20 min under stirring; extraction temperature 25 °C |

// |

[41] |

|

|

Avena sativa seeds |

GK Iringo, GK Kormorán and GK Zalán |

Aqueous solution of 0.1% (m/v) ascorbic acid and 1% (v/v) MeOH; solvent: sample ratio 6:1 (v/w); extraction time 5 h under shaking; extraction temperature 25 °C |

95.2–99.6% |

[42] |

|

|

Vicia Faba roots, sprouts, leaf, seediling, pod, flower, stem |

// |

Ethanol solution 95% (v/v); solvent: sample ratio //; extraction time 72 h in freezer; extraction temperature −18 °C |

// |

[43] |

|

|

Vicia Faba sprouts |

// |

Ethanol solution 95% (v/v); solvent: sample ratio //; extraction time 48–72 h; extraction temperature −18 °C |

// |

[44] |

|

|

Mucuna and Stizolobium pruriens seed |

M. sempervirens, M. birdwoodiana, M. macrocarpa, M. interrupta, M. paohwashanica, Stizolobium pruriens var. pruriens, S. pruriens var. utilis |

HCl 0.1 M; solvent: sample ratio 20:1 (v/w); extraction time 2 × 5–10 min; extraction temperature 100 °C with a steam bath. |

// |

[45] |

|

|

Mucuna pruriens seed |

// |

0.1 M phosphate-buffered solution (pH = 7.0); solvent: sample ratio 5000:1(v/w); extraction time 5 h; extraction temperature 25 °C under stirring. |

99.35% |

[46] |

|

|

Mucuna pruriens leaves |

// |

0.1 M phosphate-buffered solution (pH = 7.0); solvent: sample ratio 500:1 (v/w); extraction time 5 h; extraction temperature 25 °C under stirring |

98.30% |

||

|

Mucuna pruriens seed |

// |

Citric acid 58% (wt%); solvent: sample ratio 7:1; extraction time 90 min; extraction temperature 60 °C |

80–84% |

[47] |

|

|

Ultrasound-assisted solvent extraction (UASE) |

Mucuna pruriens seed |

Arka Dhanwantri |

Water acidified with 0.1 M HCl (pH: 2.6); solvent: sample ratio 10:1 (v/w); frequency 35 kHz; extraction time 5, 10, 15 min; extraction temperature 25 °C. |

(5 min) 30.7% (10 min) 25.6% (15 min) 31.5% |

[48] |

|

Arka Ashwini |

(5 min) 29.0% (10 min) 27.7% (15 min) 26.8% |

||||

|

White |

(5 min) 29.3% (10 min) 31.4% (15 min) 30.8% |

||||

|

Brown |

(5 min) 23.9% (10 min) 28.7% (15 min) 30.6% |

||||

|

Vicia faba sprouts and seeds |

// |

MeOH and water mixture (80:20); solvent: sample ratio 1:5 (v/w); frequency //; extraction time 30 min; extraction temperature 25 °C. |

// |

[49] |

|

|

Vicia faba flowers, fruits and leaves |

// |

Water boiling deionized; solvent: sample ratio 50:1 (v/w); frequency //; extraction time 15 min; extraction temperature 100 °C. |

100.32% |

[36] |

|

|

Vicia Faba seeds |

// |

HCl 10 mM 5 mL; solvent: sample ratio // (v/w); frequency //; extraction time 2 × 60 min; extraction temperature 25 °C. |

99.8% |

[50] |

|

|

Lens culinaris seeds |

105.0% |

||||

|

Vicia Faba sprouts, leaves, flowers, pods, roots |

// |

Aqueous MeOH 50% (v/v); solvent: sample ratio 200:1 (v/w); frequency //; extraction time 30 min; extraction temperature below 40 °C. |

// |

[51] |

|

|

Vicia faba seeds |

Bachus, Bolero White, Windsor Bonus, Rambo Amigo, Olga Granit, Albus Fernando, Amulet |

Aqueous CH3COOH 0.2% (v/v); solvent: sample ratio 25:1 (v/w); frequency 40 kHz; extraction time 2 × 20 min; extraction temperature 25 °C. |

// |

[15] |

|

|

Wild type legume grain |

Acacia nilotica, Bauhinia purpurea, Canavalia ensiformis, Cassia hirsuta, Caesalpinia bonducella, Erythrina indica, Mucuna gigantea, Pongamia pinnata, Sebania sesban, Xylia xylocarpa |

HCl 0.1 M; solvent: sample ratio 10:1 (v/w); frequency // kHz; extraction time 30 min and stirring for 1 h. extraction temperature 25 °C. |

// |

[52] |

|

|

Mucuna sanjappae seed |

// |

HCl 0.1 M; solvent: sample ratio 300:1 (v/w); frequency // kHz; extraction time 20 min; extraction temperature 25 °C. |

// |

[53] |

|

|

M. pruriens seeds |

Macrocarpa |

HCl 0.1 M; solvent: sample ratio 300:1 (v/w); frequency // kHz; extraction time 20 min; extraction temperature 25 °C. |

// |

[54] |

|

|

Microwave-assisted solvent extraction (MASE) |

Mucuna pruriens seed |

Arka Dhanwantri |

Water acidified with 0.1 M HCl (pH = 2.6); solvent: sample ratio 10:1 (v/w); MW power 400 W; irradiation time 5, 10, 15 min; extraction temperature 60 °C. |

(5 min) 53.5% (10 min) 58.7% (15 min) 58.4% |

[48] |

|

Arka Ashwini |

(5 min) 50.6% (10 min) 59.6% (15 min) 54.0% |

||||

|

White |

(5 min) 50.5% (10 min) 49.6% (15 min) 58.5% |

||||

|

Brown |

(5 min) 56.1% (10 min) 54.9% (15 min) 54.8% |

||||

|

Reflux extraction |

Mucuna pruriens seed |

Arka Dhanwantri |

Water acidified with 0.1 M HCl (pH = 2.6); solvent: sample ratio 10:1 (v/w); extraction time 300 min, extraction temperature 100 °C |

60.2% |

[48] |

|

Arka Ashwini |

65.7% |

||||

|

White |

57.2% |

||||

|

Brown |

59.8% |

||||

|

Mucuna pruriens powder and extracts |

// |

MeOH and 0.1 M HCl mixture (70:30); solvent: sample ratio 100:1 (v/w); extraction time 30 min; extraction temperature 25 °C |

98.83% |

[55] |

|

|

Mucuna pruriens seed |

Preta Kaunch |

HCl 0.1 M; solvent: sample ratio 2:1 (v/w); extraction time 180 min; extraction temperature 25 °C |

98.1–106.7% |

[56] |

|

|

Maceration |

Mucuna pruriens powder formulation |

// |

Water and EtOH mixture (30:70); solvent: sample ratio //; extraction time 7 days; extraction temperature cold |

94.5% |

[57] |

|

Phaseolus vulgaris dried seed, seeding and callus |

// |

HCl 0.1 M and EtOH mixture (1:1); solvent: sample ratio 1:10; extraction time 5 days; extraction temperature 25 °C |

99.55–100.27% |

[58] |

|

|

Soxhlet extraction |

Mucuna utilis seed |

// |

MeOH; solvent: sample ratio //; extraction Soxhlet time //; extract obtained sonication for 60 min with 100 mL HCl 0.1 M; extraction temperature 25 °C |

98.67–100.4% |

[59] |

// This indicates that values were not reported.

3. Levodopa Detection Methods

|

Methods |

Sample Source |

LOD Range |

Stationary Phase |

Mobile Phase |

Detection Mode |

Strengths |

Drawbacks |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HPLC-UV |

Broad bean, cocoa and beans |

10 ng/mL–15 µg/mL |

RP-C18 (mean particle diameter 5 µm, 125 × 3 mm I.D.) |

Solvent (A): acetate buffer, pH = 4.66; solvent (B): methanol |

Photodiode array detector (DAD) |

It is highly reproducible, rapid and efficient |

Sensitivity is rather limited so it is suitable for plant matrices with medium and high concentrations of LD. Selectivity is also limited since it does not allow the unambiguous identification of structurally similar molecules. |

[38] |

|

Mucuna pruriens dehulled and whole seed |

Solvent (A): water/methanol/phosphoric acid 975.5:19.5:1 (v/v/v), pH = 2.0; solvent (B): 70% methanol. |

[35] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba seeds (cotyledons and embryo axis) |

Ammonium phosphate buffer (0.05 mol/kg, pH = 2.0) |

[25] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba broad beans |

Water (H2O) and acetonitrile (ACN) both containing 0.1% (v/v%) acid formic |

[39] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba roots, sprouts, seedling, leaf, flower, pod, stem |

Solvent (A): 0.1% acetic (98%); Solvent (B): methanol (2%). |

[43] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba sprouts |

Solvent (A): 82% buffer solution (32 mM citric acid, 54.3 mM sodium acetate, 0.074 mM Na2EDTA, 0.215 mM octyl sulphate pH = 4); Solvent (B): 18% methanol |

[44] |

||||||

|

Mucuna and Stizolobium pruriens seed |

Solvent (A): 0.1 N acetic acid (90%); Solvent (B): methanol (10%) |

[45] |

||||||

|

Mucuna pruriens seed |

Solvent (A): 0.1% formic acid (98%); Solvent (B): methanol (2%) |

[48] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba flowers, fruits and leaves |

Solution of 50 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate (pH = 2.3) |

[36] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba sprouts, leaves, flowers, pods, roots |

Solvent (A): water with 0.3% formic acid; Solvent (B): acetonitrile with 0.3% formic acid |

[51] |

||||||

|

Vicia faba seeds |

Solvent (A): 97% v/v of an aqueous solution of 0.2% v/v acetic acid; Solvent (B): 3% v/v methanol |

[15] |

||||||

|

M. pruriens seeds |

Water, methanol and acetonitrile (5:3:2) containing 0.2% triethylamine, pH = 3.3 |

[54] |

||||||

|

Mucuna pruriens powder formulation |

Solvent (A): water 80% v/v; Solvent (B): methanol 20% v/v |

[57] |

||||||

|

Mucuna pruriens powder and extracts |

RP-C18 (mean particle diameter 5 µm) |

Water: Methanol: Acetonitrile (100:60:40) containing 0.2% Triethylamine, pH = 3.3 |

[55] |

|||||

|

Mucuna sanjappae Seed |

RP-C18 (250 × 4.6 mm I.D.) |

Methanol |

[53] |

|||||

|

Mucuna utilis seed |

RP-C18 (250 × 4.0 mm I.D.) |

Solvent (A):0.5% v/v of acetic acid 30%; Solvent (B): methanol 70% |

[59] |

|||||

|

LC-MS |

Vicia faba roots, sprouts and seeds |

18 µg/Kg |

RP-C18 (mean particle diameter 2.6 µm, 100 × 4.6 mm I.D.) |

Solvent (A): ultrapure water with 0.5% (v/v) formic acid 50%; Solvent (B): methanol 50% |

Photo diode array detector (DAD) and triple quadrupole (TQ) mass spectrometer |

Robust analytical technique that provides higher sensitivity and selectivity than LC-UV methods. It allows to unambiguously identify the compounds under analysis, through the possibility of fragmentation. |

It is a technique susceptible to matrix effects: co-eluting compounds could interfere with the ionization of the analyte under examination. Detection in MRM mode is to be preferred. |

[40] |

|

0.01 µg/mL |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Photo diode array detector (DAD) and quadrupole-time-of-flight (QTOF)- mass spectrometer |

[49] |

||||

|

Avena sativa seeds |

RP-C18 (mean particle diameter 4 µm, 250 × 2 mm I.D.) |

Solvent (A): solution 0.1% (v/v) of formic acid (97%); Solvent (B): ACN/MeOH 75/25 containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (3%) |

Ion Trap mass spectrometer |

[42] |

||||

|

HPTLC |

M. pruriens seeds |

Not reported |

Silica-coated aluminum sheet (10 cm × 10 cm with 0.2 mm thickness) |

n-butanol, acetic acid and water were used as mobile phase at 4:1:1 |

UV-Vis thin layer scanner |

It makes it possible to obtain a preliminary separation of the analytes in a fast, efficient, easy and low cost analysis |

It is generally employed only for qualitative analysis. It is poorly reproducible, as it works in an open system, whose environmental conditions could alter the results. |

[54] |

|

CE-UV |

Vicia faba seeds |

LOD value 0.7 µg/mL. |

47 cm (40 cm from inlet to the detector) × 75 µm i.d. fused-silica capillary |

35 mM NaH2PO4, pH = 4.55, 17.5 kV and 30 °C. |

Photo diode array detector (DAD) |

It allows faster analysis and higher efficiency than LC-UV |

It is less sensitive than HPLC-UV |

[50] |

|

Lens culinaris seeds |

||||||||

|

Electrochemical methods |

Mucuna pruriens seed, leaves |

LOD value 1.54 µM |

Working electrode: gold modified pencil graphite |

Supporting electrolyte: 0.1 M phosphate-buffered solution (pH = 7.0) |

Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) |

It makes it possible to identify and quantify the analyte in a fast and economical way, through the use of conventional or modified nanostructured electrodes, which permits a better selectivity and sensitivity of analysis. |

The technique still shows limitations especially related to the problem of electrode poisoning and oxidizable interfering compounds in the same range of anode potential. |

[46] |

|

Mucuna pruriens seed cooked and raw |

LOD value 5.12 ng/mL |

RP-C18 (mean particle diameter 3.5 µm, 150 × 2.1 mm I.D.) Working electrode: Glassy carbon |

Eluent/supporting electrolyte: 103 mM sodium acetate, 0.88 mM citric acid, 2.14 mM 1-octanesulphonic acid sodium salt with pH adjusted to 2.38 by orthophosphoric acid |

Amperometric detection at a potential of +0.7 V after micro-high performance liquid chromatography separation |

[41] |

|||

|

Sunflower seed, sesame seed, pumpkin seed and fava bean seed |

LOD value 14.3 nmol/L |

Working electrode: glassy carbon modified by graphene quantum dots decorated with Fe3O4 nanoparticles/functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes |

Supporting electrolyte: 0.1 mol/L PBS at pH = 5.5 |

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) |

[64] |

|||

|

Sweet potato |

17 nM |

Working electrode: nitrogen-doped graphene supported with nickel oxide nanocomposite |

Supporting electrolyte: 0.05 M PBS at pH = 7 |

Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) |

[65] |

|||

|

Spectrophotometry UV-Vis |

Wild type legume grain |

LOD 1.12 µg/mL |

// |

// |

// |

It is an easy to use and low-cost technique that allows both qualitative and quantitative evaluation |

It is generally not preceded by a separation step. This implies that the sample can contain interfering compounds causing potential false positives. |

[52] |

|

Phaseolus vulgaris dried seed, seeding and callus |

[58] |

|||||||

|

NMR |

Mucuna pruriens seed |

LOD value 0.0175 mg/g |

// |

// |

// |

It is a highly reproducible technique. It makes it possible to get structural details of the compounds under examination. |

Requires expensive equipment and provides low sensitivity compared to LC-MS. It is hardly used for quantification, due to the chemical noise and signal overlapping. |

[56] |

// This indicates that values were not reported.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/separations9080224