Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to governments in 157 countries introducing lockdowns or re-strictions to people’s movement and access to health and welfare support services as well as other rules including social distancing, use of masks, and quarantine. The French government introduced its first mandatory national lockdown on 17 March 2020 due to elevated cases and death rates of COVID-19 in the country. This public health measure required the general population to stay at home except those carrying out an essential job (referred to as a ‘key worker’ in the domains of transportation, education, food, and health), to buy necessary items, or to engage in physical activity. Evidence demonstrates that the pandemic disproportionately affected socially vul-nerable populations, including migrants. The pandemic exposed and exacerbated health and social inequities among migrant and ethnic/racial groups. Less is known about the firsthand impact of the COVID-19 lockdowns, specifically on migrant populations in France.

- COVID-19

- lockdown

- pandemic

- migrants

- asylum seekers

- crisis

- social vulnerability

- health inequities

- France

1. Defining Migrant Terminology Used in the Research

While the term refugee is precisely defined in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol 3, migrants are a heterogeneous group with no international consensus [1]. The umbrella term ‘migrant’ is defined as a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons [2]. Table 1 describes a common typology of migrants. For the purposes of this research, the researchers adopt the term “migrant” which includes the labels in Table 1.

Table 1. Defining common migrant terminology, adapted from International Organization for Migration (Reprinted/adapted with permission from ref. [2]. Copyright 2021, J. Redpath-Cross & R. Perruchoud).

| Asylum Seeker | A person who seeks safety from persecution or serious harm in a country other than his or her own and awaits a decision on the application for refugee status under relevant international and national instruments. |

| Economic Migrant | A person leaving his or her habitual place of residence to settle outside his or her country of origin in order to improve his or her quality of life. This term is often loosely used to distinguish from refugees fleeing persecution and is also similarly used to refer to persons attempting to enter a country without legal permission and/or using asylum procedures without bona fide cause. It may equally be applied to persons leaving their country of origin for the purpose of employment. |

| Irregular Migrant | A person who, owing to unauthorized entry, breach of a condition of entry or the expiration of his or her visa, lacks legal status in a transit or host country. The definition covers, inter alia, those persons who have entered a transit or host country lawfully but have stayed for a longer period than authorized or subsequently taken up unauthorized employment (also called clandestine/undocumented migrant or migrant in an irregular situation). The term ‘irregular’ is preferable to ‘illegal’ because the latter carries a criminal connotation and is seen as denying migrants’ humanity. |

This is a condensed list and is not exhaustive.

Their asylum case at the host country with the aim of obtaining refugee status, they may also be documented or ‘undocumented’ (“sans papiers” in French). There is also no universally accepted definition of ‘irregular’ migration. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines it as “movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit, and receiving country” [2]. From the perspective of destination countries, it refers to entry, stay, or work in a country without the necessary authorization or documents required under immigration regulations. Migrants escaping conflict and persecution in their countries and seeking protection in another country may be counted as undocumented migrants at the moment of crossing the border, but their status may change once they apply for asylum [3][4] or are regularized.

2. Social Vulnerability: A Conceptual Lens to Understand the Experiences of Migrants

The concept of social vulnerability is used across a variety of fields and disciplines, including global health, development, disaster management, economics, sociology, anthropology, geography, and environmental studies. The concept emerged within the natural hazards and disaster management literature, emphasizing the exposure risk and the amount of damage caused by a particular hazard from a technical or engineering sciences perspective [5][6]. Rather than simply examining risk exposures, social scientists transformed the concept to consider the vulnerability that pre-exists in a system before it encounters a hazard.

The negative impact of a pandemic on migrant health and well-being are exacerbated by antecedent social determinants, including poverty, discrimination, social exclusion, low levels of education, poor public infrastructure, and uneven distribution of resources that amplify social vulnerability [5][7][8]. From this perspective, the COVID-19 pandemic is conceptualized as a crisis or disruptive event that occurs at a rate and magnitude that exceeds normal capacity (e.g., increasing cases, hospitalization, and death rates of COVID-19).

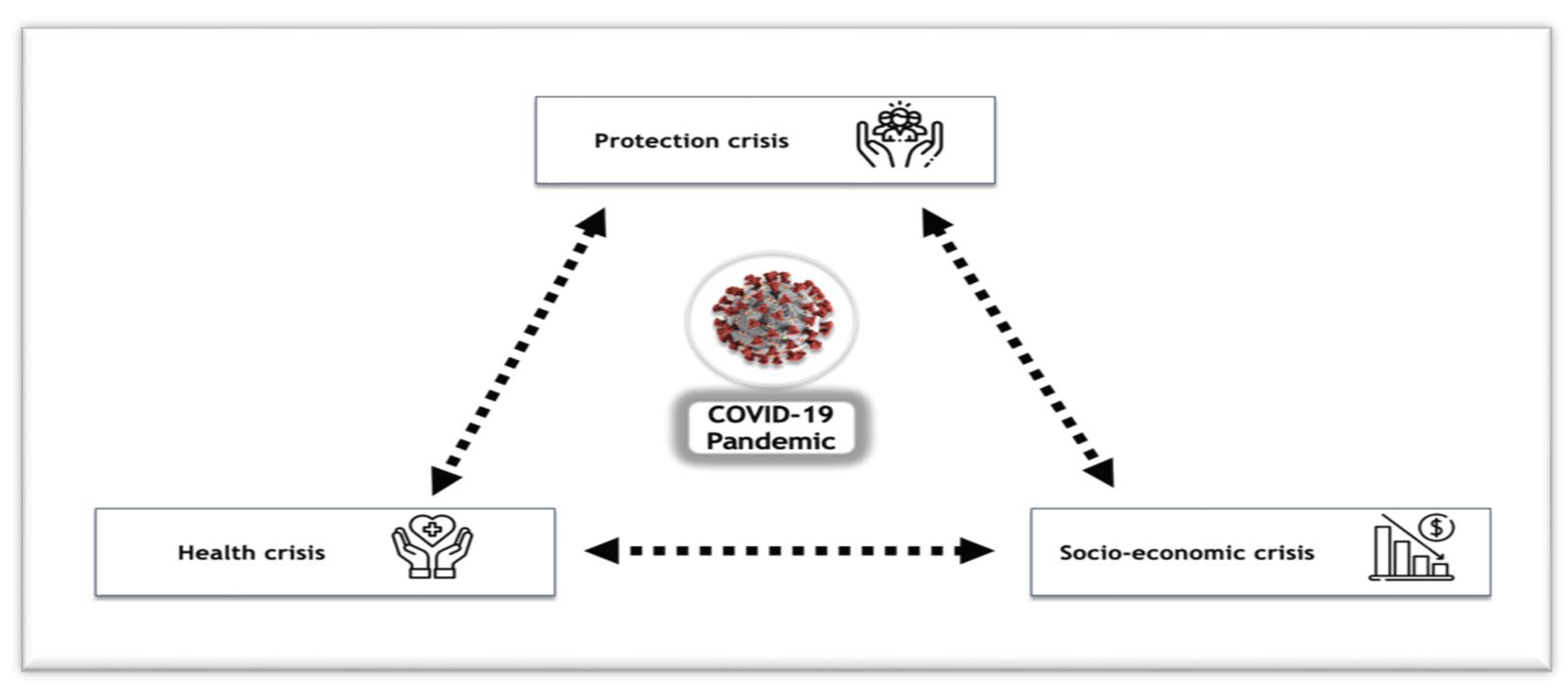

In this entry, the researchers adopt the lens of social vulnerability as a conceptual framework to help interpret the impact of the pandemic and consequential lockdown. The notion in this framework is that a ‘compounded crisis’, which encompasses a health crisis, a protection crisis, and a socio-economic crisis [9], arises from existing vulnerabilities reinforcing each other and is amplified during a pandemic and subsequent lockdown, creating a detrimental cycle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Social vulnerability: a conceptual framework to interpret the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown on migrants (adapted from UN Sustainable Development Group) (Reprinted/adapted with permission from ref. [10]. Copyright 2021, UN Sustainable Development Group).

3. A Health Crisis

Data from the World Health Organization (2020) demonstrated that 93% of countries experienced disruption in one or more of their services for mental, neurological, and sub-stance use disorders [11]. Mental health services were cut during the pandemic, given the insufficient number of health workers, the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and the conversion of mental health facilities to quarantine/treatment facilities [12]. The pandemic, therefore, led to worsened pre-existing mental health outcomes or to new con-ditions among migrants [12][13][14][15][16].

Apart from the U.K, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland, European countries did not report COVID-19 statistics according to migrant status or ethnicity [17]. Scandinavian countries reported higher rates of COVID-19 cases, mortality, and morbidity among migrant populations [18]. For example, in Sweden, in comparison to Swedish-born individuals, migrants from Somalia faced a ninefold excess risk in mortality, sixfold for migrants from Lebanon, fivefold for migrants from Syria, and a two-to-threefold for migrants from Turkey, Iran, and Iraq [18]. In Denmark, migrants of non-Western origins comprised 15% of COVID-19 hospital admissions despite constituting 9% of the total population [18]. In France, population-wide data on morbidity and healthcare are not col-lected according to ethnic and migrant status [19]. However, data on all-cause mortality rates revealed that persons who are foreign-born had, on average, double the rates of all-cause mortality (some of which were due to COVID-19) compared with the native-French population between March and April 2020, when the virus was surging [20]. Excess COVID-19-related mortality (i.e., a 118% increase compared with the preceding year) was also observed in Seine-Saint-Denis (located in the North of Paris), the poorest district in France with the highest immigrant population (30% in comparison to France’s at 10%) [21][22].

Furthermore, the stringent measures towards migrants regarding healthcare provision in France have made it more difficult for migrants to seek healthcare. The 2019 L’aide médicale de l’État (AME), or Federal Medical Assistance reform, meant that asylum seekers must complete a 3-month “délai de carence” (waiting period) in France prior to accessing basic healthcare coverage. New restrictions on the type of care available were also introduced, for example, excluding psychiatric support [23].

4. A Protection Crisis

Most governments instituted measures such as social distancing, lockdown proce-dures, and mask mandates in response to COVID-19 case and death rates at the time [24][25][26]. Implementing government-mandated COVID-19 precaution measures proved particularly challenging for migrants residing in precarious living conditions, which con-tributed to increased vulnerabilities and a protection crisis, and in turn, elevated risk for COVID-19 infection and death among this population, as described above.

Unsanitary and overcrowded living conditions were already an existing issue prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and were exacerbated during the lockdown and the pandemic. For example, the Moria camp in Lesbos, Greece dubbed as “Moria jungle,” housed 17,000 migrants above capacity and eventually burnt down in September 2020, leaving over 20,000 residents without shelter [27]. Perilous conditions were not restricted to migrant camps in the Mediterranean; many urban and perceived ‘progressive’ states have fostered the same adverse living conditions. In November 2020, the French police destroyed a mi-grant camp at the Place de la République in central Paris [28]. The substandard living conditions in the French capital saw migrants with little to no access to sanitation facili-ties and reliant on food donation points by local organizations and civil society [28]. Over 85% of respondents slept in tents, under bridges, or on damp mattresses on the floor [28]. Between 2015 and 2017, the unhygienic and overcrowded conditions combined with a lack of essential resources (e.g., hygiene products) led to recurring outbreaks of scabies [29]. Overall, these adverse physical environmental conditions further augment the popu-lation’s vulnerability to disease outbreaks. These living conditions were worsened during the COVID-19 lockdown and the pandemic.

5. A Socioeconomic Crisis

Migrants face major hurdles in economic integration in France, given that they have little to no access to the labor market [30]. Undocumented migrants face de jure work restrictions (i.e., not legally permitted to work given that they are not afforded the same labor rights in law as citizens) and de facto struggles when working illegally [30]. Most migrants who work are limited to the informal sector with no protections and, thus, higher vulnerabilities.

Evidence highlights the economic and labor challenges faced by migrants due to the COVID-19 pandemic, including increased difficulty in accessing informal labor market participation [24]. The International Labour Organization (ILO) found that these informal sectors were highly impacted by the pandemic, leading to the widespread loss of livelihood and the resultant poverty increase among migrants in Europe [31]. The loss of jobs and informal income-generating opportunities, therefore, led to even deeper financial and food insecurity for migrants than before the pandemic [28].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph191610084

References

- UN General Assembly. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees; United Nations, Treaty Series, 189, 137; Institute of Jewish Affairs: London, UK, 1951; Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Redpath-Cross, J.; Perruchoud, R. Glossary on Migration; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.iom.int/glossary-migration (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Vespe, M.; Natale, F.; Pappalardo, L. Datasets on Irregular Migration and Irregular Migrants in the EU. IOM, 2017; pp. 26–33. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC107749 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- International Organization for Migration. IOM World Migration Report. International Organization for Migration, 2018; pp. 1–359. Available online: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/country/docs/china/r5_world_migration_report_2018_en.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Ge, Y.; Dou, W.; Zhang, H. A new framework for understanding urban social vulnerability from a network perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1723.

- Burton, C.; Rufat, S.; Tate, E. Social Vulnerability: Conceptual Foundations and Geospatial Modeling. In Vulnerability and Resilience to Natural Hazards; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018.

- Page, K.R.; Venkataramani, M.; Beyrer, C.; Polk, S. Undocumented U.S. immigrants and COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e62.

- Kim, S.J.; Bostwick, W. Social vulnerability and racial inequality in COVID-19 deaths in Chicago. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 509–513.

- Kruczkiewicz, A.; Klopp, J.; Fisher, J.; Mason, S.; McClain, S.; Sheekh, N.M.; Moss, R.; Parks, R.M.; Braneon, C. Compound risks and complex emergencies require new approaches to preparedness. PNAS 2021, 118, e2106795118.

- UN Sustainable Development Group. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and People on the Move. 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-people-move (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Disrupting Mental Health Services in Most Countries, WHO Survey. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2020-covid-19-disrupting-mental-health-services-in-most-countries-who-survey (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Pinzón-Espinosa, J.; Valdés-Florido, M.J.; Riboldi, I.; Baysak, E.; Vieta, E. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280, 407–408.

- Júnior, J.G.; de Sales, J.P.; Moreira, M.M.; Pinheiro, W.R.; Lima, C.K.T.; Neto, M.L.R. A crisis within the crisis: The mental health situation of refugees in the world during the 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 280, 407–408.

- Dalexis, R.D.; Cénat, J.M. Asylum seekers working in Quebec (Canada) during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk of deportation, and threats to physical and mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113299.

- Kenny, M.A.; Grech, C.; Procter, N. A trauma informed response to COVID 19 and the deteriorating mental health of refugees and asylum seekers with insecure status in Australia. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 31, 62–69.

- Mukumbang, F.C.; Ambe, A.N.; Adebiyi, B.O. Unspoken inequality: How COVID-19 has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities of asylum-seekers, refugees, and undocumented migrants in South Africa. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 141.

- Simon, P. The failure of the importation of ethno-racial statistics in Europe: Debates and controversies. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2017, 40, 2326–2332.

- Vist Gunn, E.; Arentz-Hansen, E.H.; Vedoy, T.F.; Spilker, R.S.; Hafstad, E.V.; Giske, L. Incidence and Severe Outcomes from COVID-19 among Immigrant and Minority Ethnic Groups and among Groups of Different Socio-Economic Status: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2021/incidence-and-severe-outcomes-from-covid-19-among-immigrant-and-minority-ethnic-groups-and-among-groups-of-different-socio-economic-status-report-2021.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Melchior, M.; Desgrées du Loû, A.; Gosselin, A.; Datta, G.D.; Carabali, M.; Merckx, J.; Kaufman, J.S. Migrant status, ethnicity and COVID-19: More accurate European data are greatly needed. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 160–162.

- Papon, S.; Robert-Bobée, I. Une hausse des décès deux fois plus forte pour les personnes nées à l’étranger que pour celles nées en France en mars-avril 2020. INSEE Focus 2020, 198, 160–162. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4627049 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- L’Institut Paris Region. La Surmortalité Durant L’épidémie de COVID-19 Dans les Départements Franciliens. 2020. Available online: https://www.ors-idf.org/nos-travaux/publications/la-surmortalite-durant-lepidemie-de-covid-19-dans-les-departements-franciliens.html (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Fouillet, A.; Pontais, I.; Caserio-Schönemann, C. Excess all-cause mortality during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in France. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2020, 25, 34.

- Stone, J. Macron Plans to Bar Refugees from Accessing Medical Care. The Independent, 2019. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/emmanuel-macron-migrants-refugee-access-medical-care-immigration-latest-a9188166.html (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The Territorial Impact of COVID-19: Managing the Crisis across Levels of Government. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government-d3e314e1 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Financial Times Visual & Data Journalism Team. Lockdowns Compared: Tracking Governments’ Coronavirus Responses. 2021. Available online: https://ig.ft.com/coronavirus-lockdowns (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Haug, N.; Geyrhofer, L.; Londei, A.; Dervic, E.; Desvars-Larrive, A.; Loreto, V.; Pinior, B.; Thurner, S.; Klimek, P. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 1303–1312.

- BBC. Lesbos: Greek Police Move Migrants to New Camp after Moira Fire. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54189073 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Byrne, M. On the streets of Paris: The experience of displaced migrants and refugees. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 130.

- Par, C.B. Paris: Retour de la Gale Parmi les Réfugiés. LeParisien, 2017. Available online: https://www.leparisien.fr/paris-75/paris-75018/paris-retour-de-la-gale-parmi-les-refugies-15-06-2017-7055208.php (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Louarn, A.-D. The Risks of Working Illegally in France. 2018. Available online: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/7067/the-risks-of-working-illegally-in-france (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Impact of Lockdown Measures on the Informal Economy. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743534.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!