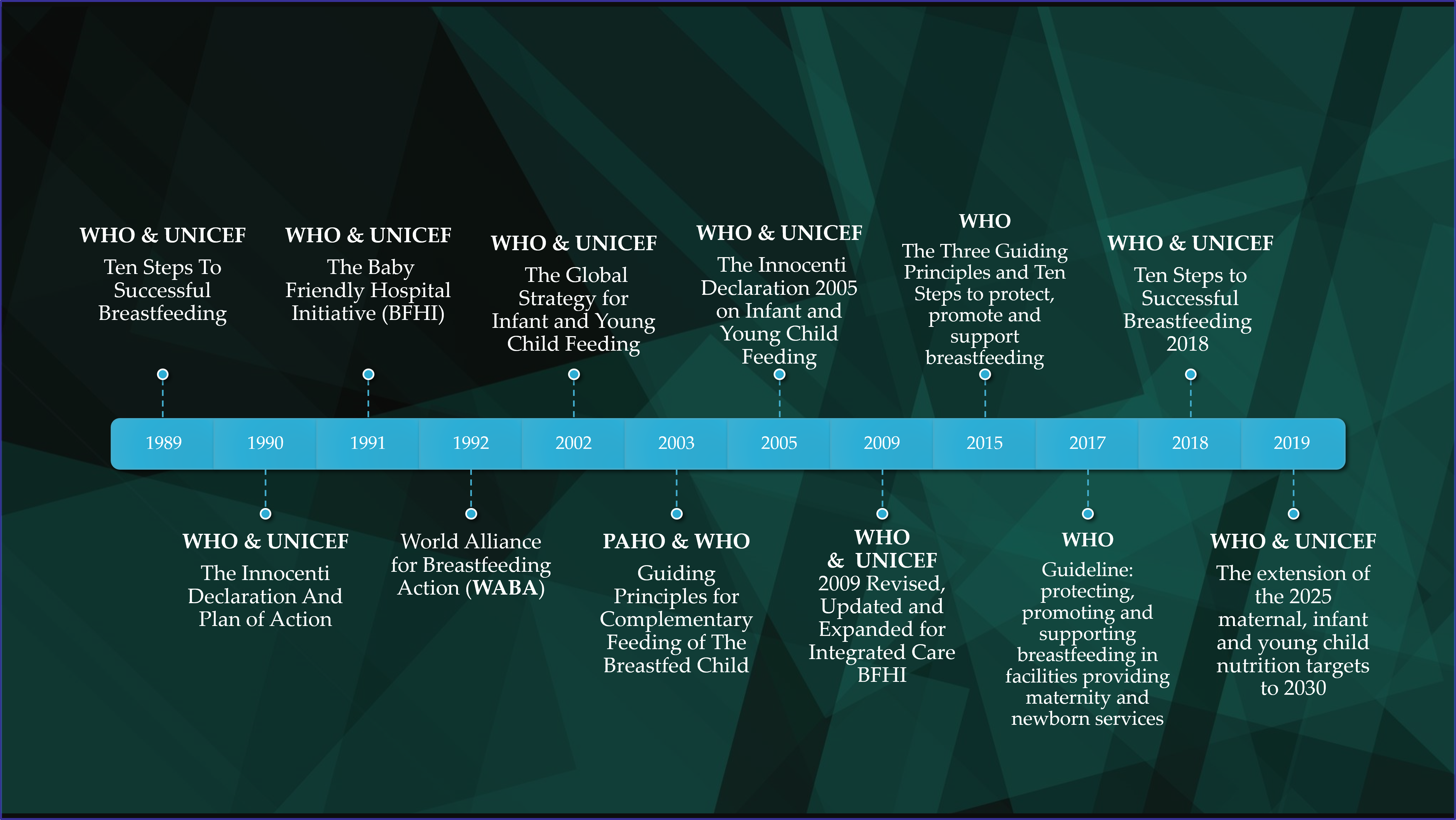

Childhood malnutrition is a global epidemic with significant public health ramifications. The alarming increase in childhood obesity rates, in conjunction with the COVID-19 pandemic, pose major challenges. Since the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 and the joint consortium held by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) that led to the “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding”, several policymakers and scientific societies have produced relevant reports. Today, the WHO and UNICEF remain the key players on the field, elaborating the guidelines shaped by international expert teams over time, but there is still a long way to go before assuring the health of our children.

- nutrition policies

- breastfeeding policies

- childhood malnutrition

- infants

- young children

1. Introduction

2. A Roadmap of Global and European Policies Promoting Healthy Nutrition for Infants andYoung Children.

2.1. Breastfeeding, Complementary Feeding and Young Child Feeding Promotion

2.2. Severe Malnutrition Prevention and Management

2.3. Prevention of Childhood Overweight and Obesity

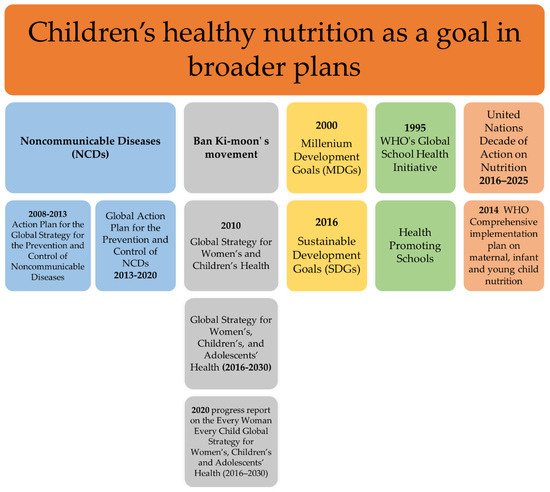

2.4. Children’s Healthy Nutrition as a Goal in Broader Plans

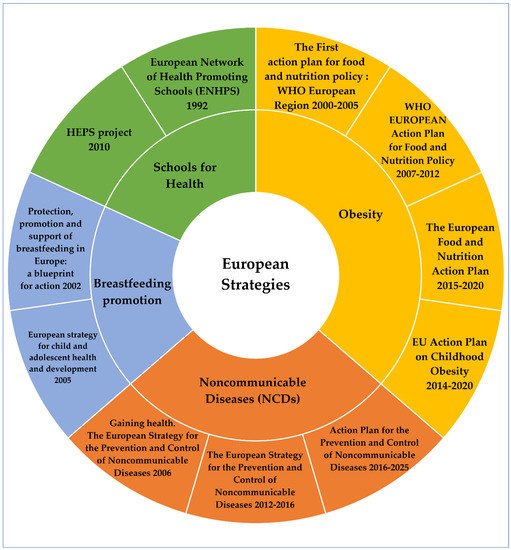

2.5. Strategies and Action Plans in the European Region

3. Discussion

| Policies | Publication Year | Organization | Target Population |

| Health Promoting Schools | NA | WHO | International |

| Extended International (IOTF) Body Mass Index Cut-Offs for Thinness, Overweight and Obesity in Children | NA | IOTF | International |

| Gaining health. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases | 2006 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases | 2009 | WHO | International |

| Healthy Eating and Physical activity in Schools (HEPS) project | 2010 | The Schools for Health in Europe network (SHE) | Europe |

| Action plan for implementation of the European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012−2016 | 2012 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020 | 2013 | WHO | International |

| WHO Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition | 2014 | WHO | International |

| EU Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014–2020 | 2014 | European Commission | Europe |

| European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020 | 2015 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity | 2016 | WHO | International |

| Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region 2016–2025 | 2016 | WHO Europe | Europe |

| Guideline: assessing and managing children at primary health-care facilities to prevent overweight and obesity in the context of the double burden of malnutrition | 2017 | WHO | International |

| Protect the progress: rise, refocus and recover | 2020 | WHO & UNICEF | International |

4. Conclusions

Since 2003, when the executive heads of WHO and UNICEF announced that “There can be no delay in applying the accumulated knowledge and experience to help make our world a truly fit environment where all children can thrive and achieve their full potential”, remarkable efforts have been made to address the problem of childhood malnutrition. Current health estimates, however, show significant delays on the progress. The children of the world hope for food security and equity in resources, indicating that considerable steps are pending.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/children9081179

References

- Vassilakou, T. Childhood Malnutrition: Time for Action. Children 2021, 8, 103.

- World Health Organization. Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74.

- Biesalski, H.K.; O’Mealy, P. Hidden Hunger, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Hunger and Food Insecurity. Available online: https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture. Definitions of Food Security. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Safeguarding against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- Food Security Information Network. Global Report on Food Crises; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates: Key Findings of the 2020 Edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Cheryl, D.; Fryar, M.S.P.H.; Margaret, D.; Carroll, M.S.P.H.; Afful, J. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity among Children and Adolescents Aged 2–19 Years: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018; NCHS Health E-Stats: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). Report on the Fourth Round of Data Collection 2015–2017; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021.

- Stavridou, A.; Kapsali, E.; Panagouli, E.; Thirios, A.; Polychronis, K.; Bacopoulou, F.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Obesity in Children and Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2021, 8, 135.

- Lange, S.J.; Kompaniyets, L.; Freedman, D.S.; Kraus, E.M.; Porter, R. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years—United States, 2018–2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1278.

- International Food Policy Research Institute. 2014 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hidden Hunger; Welthungerhilfe, International Food Policy Research Institute: Bonn, Germany; Washington, DC, USA; Concern Worldwide: Dublin, Ireland, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Nieman, P.; Leblanc, C.M. Psychosocial aspects of child and adolescent obesity. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 17, 205–208.

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A.K.; Sofi, N.Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 187–192.

- Lifshitz, F. Obesity in children. J. Clin. Res. Pediatric Endocrinol. 2008, 1, 53–60.

- Marshall, N.E.; Abrams, B.; Barbour, L.A.; Catalano, P.; Christian, P.; Friedman, J.E.; Hay, W.W., Jr.; Hernandez, T.L.; Krebs, N.F.; Oken, E.; et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: Lifelong consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 607–632.

- Moore, B.F.; Harrall, K.K.; Sauder, K.A.; Glueck, D.H.; Dabelea, D. Neonatal Adiposity and Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200737.

- Walters, E.; Edwards, R.G. Further thoughts regarding evidence offered in support of the ‘Barker hypothesis’. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2004, 9, 129–131.

- Barker, D.J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Forsen, T.; Osmond, C. Fetal origins of adult disease: Strength of effects and biological basis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 1235–1239.

- Li, R.; Ware, J.; Chen, A.; Nelson, J.M.; Kmet, J.M.; Parks, S.E.; Morrow, A.L.; Chen, J.; Perrine, C.G. Breastfeeding and Post-perinatal Infant Deaths in the United States, A National Prospective Cohort Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 5, 100094.

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.; Franca, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490.

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breast-Feeding: The Special Role of Maternity Services; 9241561300; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). On the Protection, Promotion, and Support of Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding in the 1990s: Global Initiative; Spedale degli Innocenti: Florence, Italy, 1990.

- UNICEF. World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children and Plan of Action for Implementing the World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children; United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

- World Health Organization. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi/en/index.html (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action. World Breastfeeding Week (WBW). Available online: https://waba.org.my/wbw/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. In Report of an Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding; 9241562218; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Pan American Health Organization; WHO. Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child; Division of Health Promotion and Protection/Food and Nutrition Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- UNICEF. 1990–2005 Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding; UNICEF: Florence, Italy, 2005.

- UNICEF. Innocenti Declaration on Infant and Young Child Feeding; UNICEF: Florence, Italy, 2005.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative, revised, updated and expanded for integrated care, Section 2. Strengthening and sustaining the baby-friendly hospital initiative: A course for de-cision-makers; Section 3. In Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in a Baby-Friendly Hospital: A 20-Hour Course for Maternity Staff; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Nyqvist, K.H.; Maastrup, R.; Hansen, M.; Haggkvist, A.; Hannula, L.; Ezeonodo, A.; Kylberg, E.; Haiek, L. Neo-BFHI: The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative for Neonatal Wards; Nordic and Quebec Working Group: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: Implementing the Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The Extension of the 2025 Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition Targets to 2030; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Breast-Feeding Practices: Report of an Informal Meeting; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991.

- World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Definitions and Measurement Methods; 9240018387; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding Counselling: A training Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling: An Integrated Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Early Essential Newborn Care: Clinical Practice Pocket Guide; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Essential Newborn Care Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- World Health Organization. International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1981.

- World Health Organization. Country Implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes: Status Report 2011; 9241505982; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malnutrition: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- World Health Organization. Management of the Child with a Serious Infection or Severe Malnutrition: Guidelines for Care at the First-Referral Level in Developing Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Updates on the Management of Severe ACUTE malnutrition in Infants and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 6–54.

- WHO; UNICEF; WFP; UNSCN. Community-Based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children’s Fund; 9280641476; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; WFP: Rome, Italy; UNSCN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- World Health Organization. Community-Based Strategies for Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in Developing Countries; 9241591218; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Assessing and Managing Children at Primary Health-Care Facilities to Prevent Overweight and Obesity in the Context of the Double Burden of Malnutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- United Nations. We Can End Poverty. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/poverty.shtml (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- United Nations. Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/environ.shtml (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- United Nations. We Can End Poverty. Millennium Development Goals and beyond 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Ban Ki-moon, B. Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/goals/goal-2/en/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. Every Woman Every Child—The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030): Survive, Thrive, Transform; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protect the Progress: Rise, Refocus and Recover: 2020 Progress Report on the “Every Woman Every Child Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health” (2016–2030); 9240011994; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition. United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025; A/RES/70/259; United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition: Rome, Italy, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Implementation Plan on Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition; No. WHO/NMH/NHD/14.1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Health Promoting Schools. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-promoting-schools#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- World Health Organization Assembly. Fifty-Third World Health Assembly, Geneva, 15–20 May 2000: Resolutions and Decisions, Annex; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Cattaneo, A. Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding in Europe: A Blueprint for Action; EU Project Contract N. SPC; Unit for Health Services Research and International Health: Trieste, Italy, 2004; p. 2002359.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. European Strategy for Child and Adolescent Health and Development; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005.

- European Commission. EU Action Plan on Childhood Obesity 2014–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- World Health Organization. European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020; Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy 2007–2012; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The First Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy: WHO European Region 2000–2005; Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001.

- Barnekov, V.; Buijs, G.; Clift, S.; Jensen, B.; Paulus, P.; Rivett, D.; Young, I. The Health Promoting School: A Resource for Developing Indicators; International Planning Committee of the European Network of Health Promoting Schools: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006.

- The Schools for Health in Europe Network (SHE). Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/child-and-adolescent-health/the-schools-for-health-in-europe-network-she (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Simovska, V.; Dadaczynski, K.; Viig, N.G.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Bowker, S.; Woynarowska, B.; de Ruiter, S.; Buijs, G. HEPS Tool for Schools: A Guide for School Policy Development on Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. HEPS: Woerden, The Netherlands, 2010.

- European Union. Healthy Food for a Healthy Future Best-ReMaP Joint Action of the European Union. Available online: https://bestremap.eu/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- WHO/Europe. Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region; Resolution EUR/RC56/R2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- WHO/Europe. Gaining Health. The European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for Implementation of the European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012–2016; 9289002689; Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002, 246, 1–190.

- Gama, A.; Rosado-Marques, V.; Machado-Rodrigues, A.M.; Nogueira, H.; MourAo, I.; Padez, C. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in 3-to-10-year-old children: Assessment of different cut-off criteria WHO-IOTF. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2020, 92, e20190449.

- International Association for the Study of Obesity. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20040824052003/http://www.iotf.org/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations Treaty Ser. 1989, 1577, 1–23.

- World Health Assembly. Reducing Health Inequities through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- United Nations. World Social Report 2020; Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- World Health Organization Europe. The Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies for Response; World Health Organization Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- World Health Organization. Sexual, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health Policy Survey, 2018–2019: Summary Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Akseer, N.; Kandru, G.; Keats, E.C.; Bhutta, Z.A. COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation strategies: Implications for maternal and child health and nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 251–256.

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Cunningham, K.; Moran, V.H. COVID-19 and maternal and child food and nutrition insecurity: A complex syndemic. Matern. Amp Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13036.

- Ntambara, J.; Chu, M. The risk to child nutrition during and after COVID-19 pandemic: What to expect and how to respond. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3530–3536.