Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Diabetes mellitus has become a troublesome and increasingly widespread condition. Treatment strategies for diabetes prevention in high-risk as well as in affected individuals are largely attributed to improvements in lifestyle and dietary control. Therefore, it is important to understand the nutritional factors to be used in dietary intervention.

- diabetes mellitus

- pearl millet

- nutritional importance

1. Pearl Millet and Diabetes

Pearl millet helps to keep blood sugar levels stable for a long time in diabetic patients. It is also helpful for diabetes patients because it has a comparatively small glycaemic index that helps steadily digest and contain glucose at a slower pace than other foods [1]. This will help healthy blood sugar levels for long stretches.

The amylase activity of pearl millet is very high, about 10 times than that of wheat. Maltose and D-ribose are the major sugars in the flour, and are low in fructose and glucose [2]. Diet is known as the centrepiece of diabetes mellitus treatment, especially important in the case of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), which involves the metabolism of glucose and secondary lipid and protein deficiencies as the primary derangement [3]. Diabetes dietary treatment includes reducing postprandial hyperglycaemia and strong glycaemic control. The Glycaemic Index (GI) definition originated as a physiological basis for the classification of carbohydrate foods based on the blood glycosis reaction which they consume, and was introduced by Jenkins et al. (1981) [4]. Mani et al. (1993) stated that pearl millet (Penniseteum typhoideum) is the lowest GI compared to varagu alone in addition to complete green grams (Phaseolus aureus Roxb), jowar (Sorghum vulgare), and ragi (Eleusine coracana) [5]. Low-glycaemic foods are beneficial for enhancing the metabolic regulation of blood pressure and low-density plasma lipo protein cholesterol leading to less prominent insulin reactions [6]. Several new food items based on pearl millet can be created, and conventional recipes for diabetic patients need to be supported.

It has also been shown that millet-based foods (pearl, foxtail, and finger) have been correlated with low GIs in both stable and type 2 diabetes because of their high protein level [7]. Shukla et al. (1991) found that the GR of bajra chapati was significantly lower in stable individuals than white bread. In addition, adding 30 g of fenugreek to millet chapati further decreased GI (Glycaemic Index), which resulted in less GR than that observed by the ingestion of fenugreek millet chapati. In this situation, the GR (Glycaemic Response) reduction could have been due to the quality and viscosity of the fenugreek fibre on the leaves, which may slow GE [8]. The positive relation between the proso millet intake in type 2 diabetic participants and a substantial reduction in the glucose effect has been well founded [9]. Colling et al. (1981) note that glycaemic and insulinemic responses may be influenced by the process and time taken to prepare a meal [10]. The degree of frying and the length of fermentation influenced these findings in particular.

Sukar et al. (2020) [11] showed substantial elevation of adiponectin associated with a vast decrease in blood glucose levels during the study periods. These findings imply that, feeding with the whole grain of pearl millet, a diet can play a significant role in restoring the plasma level of adiponectin to the physiological level. It is well established that an increase in adiponectin level stimulates glucose utilization through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in the skeletal muscle and liver [12], and such a diet containing pearl millet could reduce glucose level due to an enhancement of the utilization of glucose by peripheral tissues and the elevation of adiponectin levels. Many theories support the hypoglycaemic effects of pearl millet, such as the theory that pearl millet being rich in phytate and phenolic compounds reduces fasting hyperglycaemia and an attenuated postprandial blood glucose response in rats. Phenolic compounds are also known to enhance insulin activity, and pearl millet regulates intestinal GLUT, increases muscle glucose uptake, and reduces hepatic gluconeogenesis [13].

Cereal grains, especially pearl millet, are rich in antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds, as well as other important minerals. Extracts from pearl millet are reported to offer protection against DNA damage. Developing a method that can improve the nutritional profile of the natural substrate is of the utmost importance. Various researchers are using biotechnological methods for the improvement/enhancement of the bioactive compounds of cereal grains. One of the successful methods used by scientists/researchers is fermentation technology, which can manifoldly enhance the nutrients of cereal grains. Pearl millet grains are attracting attention because of the presence of certain specific bioactive constituents, their importance for health, and high nutritional values. Generally pearl millet is classified as a low-glycaemic index (GI) food because of its high fibre content. The GI assesses how much the carbohydrate content of food influences the rate and extent of change in post-prandial blood glucose concentration. Apparently, pearl millet, as a low-GI food, helps lower blood glucose available for triacylglycerol synthesis. Besides, millets condense VLDL cholesterol, a carrier of triacylglycerol in plasma, lowering triacylglycerol levels even further. As a result, the consumption of millet grains may play an important role in lowering the level of blood lipids [14].

Prediabetes is a state of elevated plasma glucose in which the threshold for diabetes has not yet been reached and can be predispose to the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Insulin resistance and impaired beta-cell function are often already present in prediabetes. Hyperglycaemia can upregulate markers of chronic inflammation and contribute to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which ultimately cause vascular dysfunction. Conversely, increased oxidative stress and inflammation can lead to insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion. Thus, the inhibition of ROS overproduction is crucial for delaying the onset of diabetes and for the prevention of cardiovascular complications. Many kinds of bioactive compounds—such as polyphenols, most flavonoids, and phenolic acids—naturally occur in millet, which might offer various health benefits, as seen in their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [15].

The close correlation between millet consumption and decreased insulin response has already been confirmed. Shukla et al. (1991) found no major variations in IR in stable and type 2 diabetic individuals after the ingestion of pearl millet, while white bread developed somewhat less of an insulin response in type 2 diabetics 1 h after treatment. In stable people, pearl millet demonstrated low GIs and a high insulinemic index; however, the same was true for those with type 2 diabetes with high GIs and a low insulinemic index. The authors observed that pearl millet evoked insulin separation in healthy persons, which decreased the gastrointestinal tract, whereas the insulin reserve in type 2 diabetics could have been inadequate to mobilize insulin after ingestion of pearl millet. Pearl millet is known for its valuable health benefits, primarily due to its high content of polyphenols, which have antioxidant properties [16].

Epidemiological reports have shown that millet eating communities suffer from a lower incidence of diabetes [17]. Pearl millet grains have many functional properties owing to their high fibre content, fatty acid composition, and plant chemicals [18]. The gained understanding of the nutritional effects of pearl millet is of considerable significance in nutritional programmes. Diabetes may usually be caused by hereditary predispositions, obesity, and a heavy intake of high-glycaemic foods. Nani et al. (2015) measured the impact of pearl millet intake on diabetic rat glucose metabolism. The authors suggested that eating pearl millet-based meals could be helpful in fixing type 2 diabetes with induced hyperglycaemia, thereby reducing the severity of the condition, as an alternative to prevention [19]. Hegde et al., (2005) have found that food animals with 55% kodo millet food have decreased hyperglycaemia by 42%, cholesterol by 27%, and non-enzymatic antioxidants (Glutathione, vitamin E, and C) and enzymatic levels by 27% (glutathione reductase) [20]. Millet grains have a greater slow digestible starch quality than some other cereals due to the characteristics of starch, including amylase content, granular structures (polygonal size with porous surfaces), fatty acid volumes, and types (oleic acid content) capable of forming complications with starch molecules and lipid inter-acid starch protein [21]. In addition, the existence of phytochemicals (phenolic acids, flavonoids, and phytats) can lead to inhibiting the activity in monosaecharides of gastrointestinal α-amylase (pancreatics) and α-glycosidase (intestinal) enzymes, reducing the body’s hyperglycaemic presence [22]. However, the method of processing applied to millets will greatly influence the hypoglycaemic character, so it is important to promote the implementation of processes that sustain low starch hydrolysis [23]. Relative to other cereal products, pearl millet produces high amounts of leucine amino acid, inducing insulin secretion through down regulation of adrenergic alpha 2A receptor surface expression via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways (Leucine secretion pathway). These features are the preferred grains of pearl millet for the treatment of insulin and cardiovascular problems in type 2 diabetes [24].

Some in vivo experiments were performed to research the effect of pearl millet grains on diabetes. In one research, the impact on glucose and insulin responses in diabetic people was assessed in six typical Sudanese carbohydrate-rich meals. A slightly lower response to postprandial glucose and insulin was shown for pearl millet acid (porridge) followed by wheat gorasa (pancakes), while maize acid triggered a higher postprandial glucose and insulin response [25]. Another study showed substantially decreased levels of non-enzymatic antioxidants (glutathione, vitamin E, and vitamin C), enzymatic antioxidants (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase), and lipid peroxides of diabetes in normal amounts compared to pearl millet-fed populations [19]. Therefore, pearl millet is also very effective in diabetes management. It gradually digests and contributes glucose to the blood at a higher rate relative to other foods due to its high fibre content. This helps to maintain a steady blood sugar level in diabetic patients for a long time.

2. Pearl Millet in the Human Disease Management System

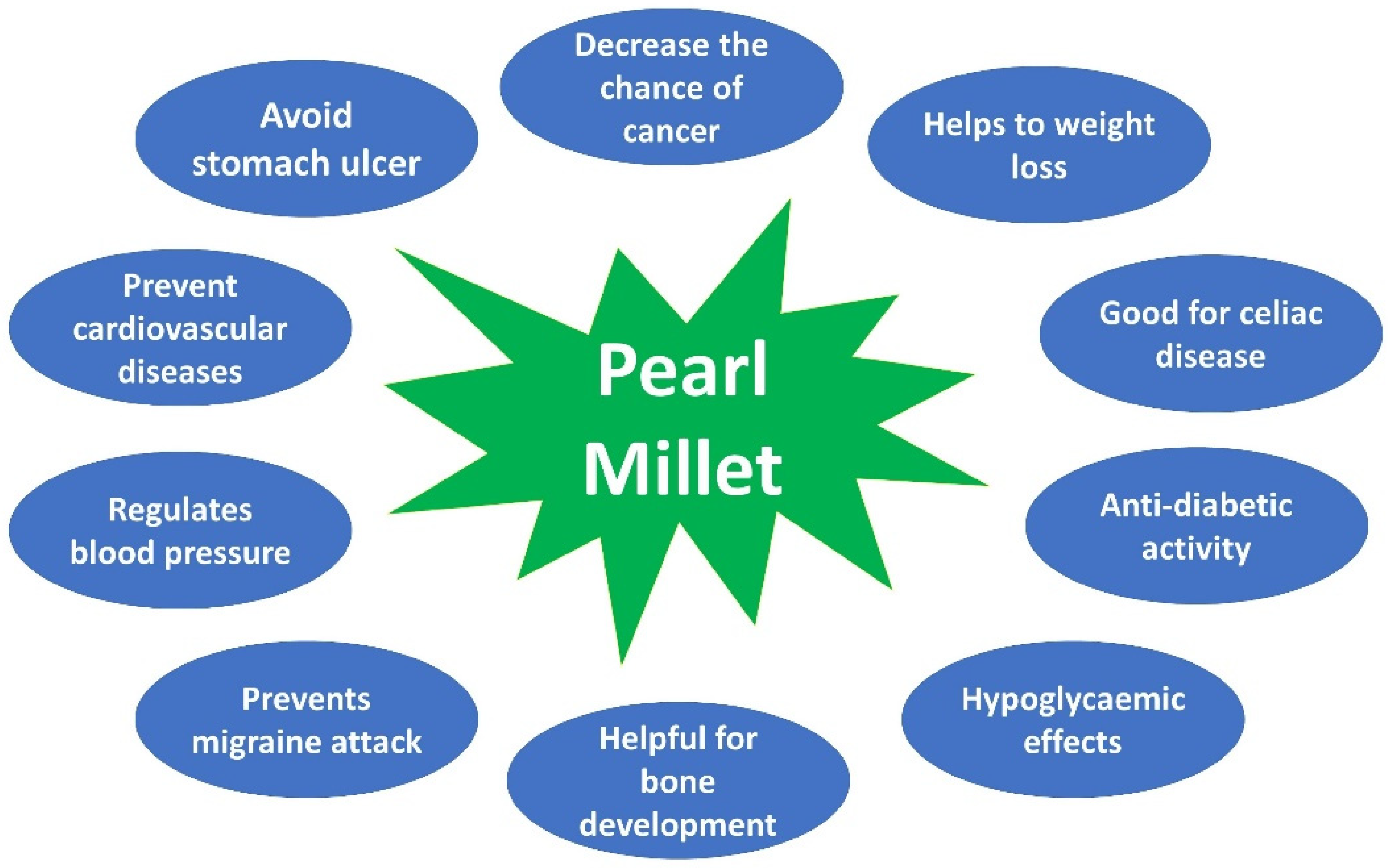

Pearl millet has many nutritional benefits as a result of its rich structure of minerals and proteins. It has high protein content, and it comprises several significant minerals such as magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, etc. It also provides vital amino acids and vitamins that add to a variety of human treatments (Figure 1) [21].

Figure 1. General Biomedical Application of Pearl Millet.

Excess acidity in the stomach following food consumption is the most important explanation for stomach ulcers [26]. Generally, pearl millet is suggested for stomach ulcer treatment, because it is one of the very few grains that alkalizes the stomach and prevents stomach ulcers or decreases the effect of ulcers [27]. Lignin and phytonutrients are good antioxidants in pearl millets that prevent cardiovascular diseases [28]. Pearl millet is also considered healthy for heart protection. There have been high levels of magnesium present in pearl millet, which regulates blood pressure and alleviates heart stress [29]. It has rich magnesium that decreases the incidence of respiratory symptoms in asthma patients and is also helpful in preventing migraine attacks [30]. Pearl millet has high phosphorus content which is very important for bone growth and development as well as for the production of ATP, the body’s energy currency [31]. As millets are known to reduce the risk of cancer, it is expected that pearl millet will have the same effect potentially due to its high content in magnesium and phylate compound [32].

The greatest obstacle facing people who wish to lose weight is to regulate their consumption of calories. Pearl millet will support the weight loss process because the fibre content is high. It takes longer for the grain to travel from the stomach to the intestines, due to the fibre content. This means the pearl millet satiates hunger for a long time and therefore helps to limit the total intake of food [33]. Celiac disease is a disorder in which a person could not endure even a little gluten in the diet. Since millet is gluten-free, it is great for people with celiac disease [34]. Pearl millet is widely recommended for people with elevated cholesterol levels. It comprises a phytochemical known as phytic acid that is estimated to influence the metabolism of cholesterol and balance the cholesterol in the body [35]. Amino acids are important to the body’s smooth activity [35]. Pearl millet is among the few foods that contain all the amino acids that are essential. Sadly, much of these amino acids are destroyed during the cooking process, as they cannot survive high temperatures because of their hypo-allergic properties. It is easier to eat these amino acids in a low cooked form in order to retain as many as possible [36]. It is also recognized that the high fibre content in pearl millet decreases the likelihood of bile incidence. The insoluble fibre content in pearl millet decreases the system’s production of excess bile. Excessive bile secretion of the intestines also worsens the state of gallstones [37]. Pearl millet is safe to use in the diets of babies, lactating women, the elderly, and the convalescent [38].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14142932

References

- Saini, S.; Saxena, S.; Samtiya, M.; Puniya, M.; Dhewa, T. Potential of Underutilized Millets as Nutri-Cereal: An Overview. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 4465–4477.

- Dias-Martins, A.M.; Pessanha, K.L.F.; Pacheco, S.; Rodrigues, J.A.S.; Carvalho, C.W.P. Potential Use of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br. in Brazil: Food Security, Processing, Health Benefits and Nutritional Products. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 175–186.

- American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, S62–S67.

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Leeds, A.R.; Gassull, M.A.; Haisman, P.; Dilawari, J.; Goff, D.v; Metz, G.L.; Alberti, K.G. Dietary Fibres, Fibre Analogues, and Glucose Tolerance: Importance of Viscosity. Br. Med. J. 1978, 1, 1392–1394.

- Mani, U.v; Prabhu, B.M.; Damle, S.S.; Mani, I. Glycaemic Index of Some Commonly Consumed Foods in Western India. Asia. Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993, 2, 111–114.

- Asp, N.G. Nutritional Classification and Analysis of Food Carbohydrates. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 679S–681S.

- Geetha, K.; Yankanchi, G.M.; Hulamani, S.; Hiremath, N. Glycemic Index of Millet Based Food Mix and Its Effect on Pre-diabetic Subjects. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2732–2738.

- Shukla, K.; Narain, J.P.; Puri, P.; Gupta, A.; Bijlani, R.L.; Mahapatra, S.C.; Karmarkar, M.G. Glycaemic Response to Maize, Bajra and Barley. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1991, 35, 249–254.

- Abdelgadir, M.; Abbas, M.; Järvi, A.; Elbagir, M.; Eltom, M.; Berne, C. Glycaemic and Insulin Responses of Six Traditional Sudanese Carbohydrate-Rich Meals in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2005, 22, 213–217.

- Collings, P.; Williams, C.; MacDonald, I. Effects of Cooking on Serum Glucose and Insulin Responses to Starch. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1981, 282, 1032.

- Sukar, K.A.O.; Abdalla, R.I.; Humeda, H.S.; Alameen, A.O.; Mubarak, E.I. Effect of Pearl Millet on Glycaemic Control and Lipid Profile in Streptozocin Induced Diabetic Wistar Rat Model. Asian J. Med. Health 2020, 18, 40–51.

- Kadowaki, T.; Yamauchi, T.; Kubota, N.; Hara, K.; Ueki, K.; Tobe, K. Adiponectin and Adiponectin Receptors in Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and the Metabolic Syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1784–1792.

- Liu, I.M.; Hsu, F.L.; Chen, C.F.; Cheng, J.T. Antihyperglycemic Action of Isoferulic Acid in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 129, 631–636.

- Salar, R.K.; Purewal, S.S. Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Potential and DNA Damage Protection of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Cultivars of North Indian Region. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 126–133.

- Alzahrani, N.S.; Alshammari, G.M.; El-Ansary, A.; Yagoub, A.E.A.; Amina, M.; Saleh, A.; Yahya, M.A. Anti-Hyperlipidemia, Hypoglycemic, and Hepatoprotective Impacts of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) Grains and Their Ethanol Extract on Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1791.

- Tomar, M.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kumar, M.; Singh, S.P.; Krishnan, V.; Kansal, R.; Verma, R.; Yadav, V.K.; Dahuja, A.; Ahlawat, S.P.; et al. Nutritional composition patterns and application of multivariate analysis to evaluate indigenous Pearl millet ((Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) germplasm. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2021, 103, 104086.

- Kangama, C.O. Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) perspectives in Africa. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2021, 2, 1–7.

- Patel, S. Cereal Bran Fortified-Functional Foods for Obesity and Diabetes Management: Triumphs, Hurdles and Possibilities. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 14, 255–269.

- Nani, A.; Belarbi, M.; Ksouri-Megdiche, W.; Abdoul-Azize, S.; Benammar, C.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Hichami, A.; Khan, N.A. Effects of Polyphenols and Lipids from Pennisetum glaucum Grains on T-Cell Activation: Modulation of Ca2+ and ERK1/ERK2 Signaling. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 426.

- Hegde, P.S.; Rajasekaran, N.S.; Chandra, T.S. Effects of the Antioxidant Properties of Millet Species on Oxidative Stress and Glycemic Status in Alloxan-Induced Rats. Nutr. Res. 2005, 25, 1109–1120.

- Krishnan, R.; Meera, M.S. Pearl Millet Minerals: Effect of Processing on Bioaccessibility. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3362–3372.

- Annor, G.A.; Tyl, C.; Marcone, M.; Ragaee, S.; Marti, A. Why Do Millets Have Slower Starch and Protein Digestibility than Other Cereals? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 66, 73–83.

- Cao, H.; Chen, X. Structures Required of Flavonoids for Inhibiting Digestive Enzymes. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 929–939.

- Kam, J.; Puranik, S.; Yadav, R.; Manwaring, H.R.; Pierre, S.; Srivastava, R.K.; Yadav, R.S. Dietary Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes: How Millet Comes to Help. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1454.

- Adéoti, K.; Kouhoundé, S.H.S.; Noumavo, P.A.; Baba-Moussa, F.; Toukourou, F. Nutritional value and physicochemical composition of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) produced in Benin. J. Microbiol. Biotech. Food Sci. 2017, 7, 92–96.

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and Polyphenolics in Foods, Beverages and Spices: Antioxidant Activity and Health Effects—A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 820–897.

- Taylor, J.R.N.; Belton, P.S.; Beta, T.; Duodu, K.G. Increasing the Utilisation of Sorghum, Millets and Pseudocereals: Developments in the Science of Their Phenolic Phytochemicals, Biofortification and Protein Functionality. J. Cereal Sci. 2014, 59, 257–275.

- Devi, P.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Sathyabama, S.; Malleshi, N.; Priyadarisini, V. Health Benefits of Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana L.) Polyphenols and Dietary Fiber: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 1021–1040.

- Kajla, P.; Ambawat, S.; Singh, S.; Suman. Biofortification and Medicinal Value of Pearl Millet Flour. In Pearl Millet; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 139–157.

- Ambati, K.; Sucharitha, K.V. Millets-Review on Nutritional Profiles and Health Benefits. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2019, 10, 33943–33948.

- Malik, S. Pearl Millet-Nutritional Value and Medicinal Uses. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2015, 1, 414–418.

- Petroski, W.; Minich, D.M. Is There Such a Thing as “Anti-Nutrients”? A Narrative Review of Perceived Problematic Plant Compounds. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2929.

- Benton, D.; Young, H.A. Reducing Calorie Intake May Not Help You Lose Body Weight. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 703–714.

- Taylor, J.R.N.; Emmambux, M.N. Gluten-Free Foods and Beverages from Millets. In Gluten-Free Cereal Products and Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 119–148.

- Hassan, Z.M.; Sebola, N.A.; Mabelebele, M. The Nutritional Use of Millet Grain for Food and Feed: A Review. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10, 16.

- Krishnan, V.; Verma, P.; Saha, S.; Singh, S.; Vinutha, T.; Kumar, R.R.; Kulshreshta, A.; Singh, S.P.; Sathyavathi, T.; Sachdev, A.; et al. Polyphenol-enriched extract from pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) inhibits key enzymes involved in post prandial hyper glycemia (α-amylase, α-glucosidase) and regulates hepatic glucose uptake. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, in press.

- Ribichini, E.; Stigliano, S.; Rossi, S.; Zaccari, P.; Sacchi, M.C.; Bruno, G.; Badiali, D.; Severi, C. Role of Fibre in Nutritional Management of Pancreatic Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2219.

- Nambiar, V.S.; Sareen, N.; Shahu, T.; Desai, R.; Dhaduk, J.J.; Nambiar, S. Potential Functional Implications of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) in Health and Disease. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 62–67.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!