Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a leading cause of death worldwide. Selection of therapeutic modalities and the prognosis of affected patients are well known to be dependent not only on tumor burden, but also hepatic reserve function. Anti-viral treatments for chronic hepatitis related to a viral infection and an increase in cases of non-viral HCC associated with the aging of society have resulted in dramatic changes regarding the characteristics of HCC patients. With recent developments in therapeutic modalities for HCC, more detailed assessment of hepatic function has become an important need. Studies in which the relationship of albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) with prognosis of HCC patients was investigated were reviewed in order to evaluate the usefulness of newly developed ALBI and modified ALBI (mALBI) grades for HCC treatment, as those scoring methods are considered helpful for predicting prognosis and selecting therapeutic modalities based on expected prognosis.

- ALBI grade, modified ALBI grade, hepatocellular ca

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a leading cause of death worldwide [1,2]. In addition to liver transplantation, surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial catheter chemoembolization (TACE), and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been developed as standard treatments for each stage. It is well known that the prognosis of HCC patients is dependent not only on tumor burden but also hepatic reserve function [3,4,5].

The present review is conducted to focus on the useful predictive value of a newly developed assessment tool of hepatic function for prognosis with each modality for the treatment of patients with HCC.

1.1. Child–Pugh Classification as a Traditional Assessment Tool for Hepatic Function and Rapid Changes of Clinical Environment

Traditionally, the Child–Pugh classification has been used worldwide for a long period as a standard assessment tool for hepatic reserve function [6] because it is easy for clinicians to remember and calculate (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparisons of the Child–Pugh classification with ALBI and mALBI grades.

| Child-Pugh Classification | ALBI/mALBI Grades | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Bilirubin | score 1: <2.0 mg/dL, score 2: 2.0–3.0 mg/dL, score 3: >3.0 mg/dL |

Used (µmol/L) |

| Albumin | score 1: >3.5 g/dL, score 2: 2.8–3.5 g/dL, score 3: <2.8 g/dL |

Used (g/L) |

| Prothrombin time | score 1: >70%, score 2: 40–70%, score 3: <40% |

No use |

| Ascites | score 1: none, score 2: mild/controlled, score 3: moderate/refractory |

No use |

| Encephalopathy | score 1: none, score 2: minimal, score 3: advanced |

No use |

| Calculation for score | Sum up all scores and baseline score 5 | log10 bilirubin (µmol/L) × 0.66) + (albumin (g/L) × –0.085 |

| Classification | A 5–6 score, B 7–9 score, C 10–15 score |

ALBI grade 1: ≤−2.60, grade 2: >−2.60 to ≤−1.39, grade 3 >−1.39.mALBI grade 2a: >−2.60 to ≤−2.27. grade 2b: >−2.27 to ≤−1.39. |

ALBI grade: albumin-bilirubin grade; mALBI grade: modified ALBI grade.

The evidence-based clinical practice guideline for HCC of the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) [7] and Barcelona Clinic liver cancer staging system (BCLC) staging [8] therapeutic strategies for all HCC stages, and the subclassification for BCLC-B (intermediate) stage HCC for treatment guidance (Bolondi’s criteria [9] and Kindai criteria [10]) use Child–Pugh score/classification as an assessment method to evaluate the pretreatment hepatic reserve. In addition, clinical trends of HCC cases have shown dynamic changes. For example, the ability to treat the hepatic function of HCC patients affected by a hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has shown improvement, because of the development of effective antiviral treatments (nucleotide analog for HBV, interferon therapy and direct acting antiviral agents for HCV). Moreover, there is an increasing number of HCC patients without HBV or HCV, which has become an important issue in association with the aging of society, as those often demonstrate good hepatic function [11,12]. As a result, in Japan, the percentage of HCC patients with Child–Pugh class A has increased from 52.1% in the 1990s to 84.8% in the late 2010s [13]. Moreover, some weak points of the Child–Pugh classification have been pointed out, including subjective factors (ascites, encephalopathy), interrelated factors (serum albumin level, ascites), semi-quantitative characteristics, and a lack of statistical evidence (Table 1).

1.2. A Development of New Assessment Tool for Hepatic Function: ALBI Grade

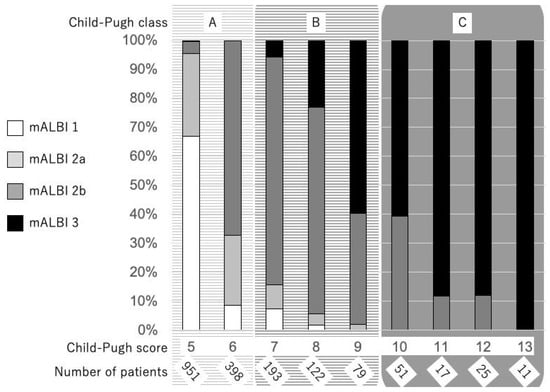

As noted above, the need for an objective and more detailed assessment tool, especially for patients with good hepatic function, has become an urgent issue. Recently, a simple and objective method for the evaluation of hepatic reserve function using only albumin and total-bilirubin measurements, termed albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade based on a formula (log10 bilirubin (µmol/L) × 0.66) + (albumin (g/L) × −0.085], has been proposed, with the values ≤−2.60, >−2.60 to ≤−1.39, and >−1.39 used to denote grades 1, 2, and 3, respectively [14]. Calculating only with two objective factors (bilirubin and albumin) is one of advantages because they are very common serum data and the frequency of a lack of data is low, especially in retrospective analyses. Following its development, it has been confirmed that ALBI grade can be used as an alternative assessment to the Child–Pugh classification, both in the evidence based clinical practice guideline for HCC of JSH (n = 3495) [15] and in the BCLC staging, with a weighted kappa value (which is a statistic for measuring the interevaluator reliability of qualitative items) of 0.917 noted with a multicenter cohort (n = 3696) [16]. As a result, ALBI grade has become recognized as a useful assessment tool for hepatic reserve function worldwide. However, a weak point of this grading system that has been pointed out is that grade 2 covers a wide range, similar to class B in the Child–Pugh classification. On the other hand, as opposed to the Child–Pugh score, which is a nominal variable, ALBI scoring has a great advantage as a continuous variable. To provide a more detailed assessment of hepatic reserve function, a modified ALBI (mALBI) grade has been proposed, with four grades including subgrades 2a and 2b, divided by the use of an ALBI score of −2.27 as the cutoff value for an indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min (ICG-R15) at 30% [17], because the ALBI score has been shown to have a correlation with ICG-R15 (r = 0.616, p < 0.001) [18]. The distribution of mALBI grades in comparison with Child–Pugh scores is shown in Figure 1 (1850 naïve HCC patients treated at Ehime Prefectural Central Hospital from 2000 to 2019). We consider that both ALBI and mALBI grades should be used for the assessment of hepatic function in patients, not only with early stage but also with intermediate and advanced stage HCC BCLC-B and -C, as they provide an opportunity to assess changes of hepatic function in detail during a clinical course (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of mALBI grades with the Child–Pugh score in 1850 HCC patients treated at Ehime Prefectural Central Hospital from 2000 to 2019.

2. Limitations of ALBI Grade

Although the ALBI score provides a good index for predicting complications following adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation and has been shown to have a predictive ability similar to that of the Child–Pugh classification and MELD score [23], the weak points of the ALBI grade with regard to the prognostic predictive power of the decompensated cirrhosis status (especially with ascites) and ruptured HCC must be kept in mind. Many clinicians have a consensus that HCC patients with uncontrollable ascites are not eligible for aggressive treatments, except for liver transplantation. In a comparison of ALBI grade and MELD in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) creation due to portal hypertension complications (variceal bleeding 55%, ascites 35%, others 10%), Khabbaz et al. reported that only MELD was associated with a transplant-free survival [78], while it was also a better predictor of both 30-day and overall survival as compared to the ALBI grade (c-index: 0.74 vs. 0.64 and 0.63 vs. 0.59, respectively) [79], while Kim et al. reported that the MELD-Na score could effectively identify hepatic function and prognosis in HCC patients with ascites when compared with ALBI, Child–Pugh and MELD scores [80]. Additionally, Wu et al. demonstrated that the Child–Pugh score could predict OS of patients with a ruptured HCC treated both with and without resection (all p < 0.0001), whereas the ALBI grade could not [81]. Needless to say, it is necessary to pay attention to the interpretation of the results in any assessment methods for hepatic reserve function in constitutional jaundice patients with an elevated bilirubin level including Gilbert’s syndrome.

3. Conclusions

ALBI and mALBI grades are worthy of clinical application for patients receiving treatments for HCC. With regards to predicting prognosis in those patients receiving curative as well as palliative treatments for u-HCC, a more detailed assessment of hepatic function provided by ALBI and mALBI grades can be used effectively in clinical situations. In the near future, the establishment of an HCC treatment algorithm using ALBI/mALBI grades is anticipated.

Reference

- Mak, L.-Y.; Cruz-Ramón, V.; Chinchilla-López, P.; Torres, H.A.; LoConte, N.K.; Rice, J.P.; Foxhall, L.E.; Sturgis, E.M.; Merrill, J.K.; Bailey, H.H.; et al. Global Epidemiology, Prevention, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.D.; Hainaut, P.; Gores, G.J.; Amadou, A.; Plymoth, A.; Roberts, L.R. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: Trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, K.; Ohtsuki, T.; Obata, H.; Tomimatsu, M.; Okazaki, N.; Hasegawa, H.; Nakajima, Y.; Ohnishi, K. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer 1985, 56, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Chung, H.; Osaki, Y. Prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma (CLIP score): Its value and limitations, and a proposal for a new staging system, the Japan Integrated Staging Score (JIS score). J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Chung, H.; Haji, S.; Osaki, Y.; Oka, H.; Seki, T.; Kasugai, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Matsunaga, T. Validation of a new prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: The JIS score compared with the CLIP score. Hepatol. (Baltimore, Md.) 2004, 40, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, R.N.H.; Murray-Lyon, I.M.; Dawson, J.L.; Pietroni, M.C.; Williams, R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. BJS 1973, 60, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokudo, N.; Hasegawa, K.; Akahane, M.; Igaki, H.; Izumi, N.; Ichida, T.; Uemoto, S.; Kaneko, S.; Kawasaki, S.; Ku, Y.; et al. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Japan Society of Hepatology 2013 update (3rd JSH-HCC Guidelines). Hepatol. Res. 2015, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, A.; Dufour, J.-F.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Piscaglia, F.; Raoul, J.L.; Sangro, B.; Bolondi, L. Heterogeneity of Patients with Intermediate (BCLC B) Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Proposal for a Subclassification to Facilitate Treatment Decisions. Semin. Liver Dis. 2013, 32, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Arizumi, T.; Ueshima, K.; Sakurai, T.; Kitano, M.; Nishida, N. Subclassification of BCLC B Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Treatment Strategies: Proposal of Modified Bolondi’s Subclassification (Kinki Criteria). Dig. Dis. 2015, 33, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, A.; Ochi, M.; Matsuda, R.; Aibiki, T.; Okudaira, T.; Kawamura, T.; Yamago, H.; Nakahara, H.; Suga, Y.; Azemoto, N.; et al. Ultrasonography screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in Japanese patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes 2015, 8, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateishi, R.; Uchino, K.; Fujiwara, N.; Takehara, T.; Okanoue, T.; Seike, M.; Yoshiji, H.; Yatsuhashi, H.; Shimizu, M.; Torimura, T.; et al. A nationwide survey on non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: 2011–2015 update. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 54, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumada, T.; Toyoda, H.; Tada, T.; Yasuda, S.; Tanaka, J. Changes in Background Liver Function in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma over 30 Years: Comparison of Child-Pugh Classification and Albumin Bilirubin Grade. Liver Cancer 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.J.; Berhane, S.; Kagebayashi, C.; Satomura, S.; Teng, M.; Reeves, H.L.; O’Beirne, J.; Fox, R.; Skowronska, A.; Palmer, D.; et al. Assessment of Liver Function in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A New Evidence-Based Approach—The ALBI Grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, A.; Kumada, T.; Kudo, M.; Hirooka, M.; Tsuji, K.; Itobayashi, E.; Kariyama, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Tajiri, K.; Ochi, H.; et al. Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) Grade as Part of the Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for HCC of the Japan Society of Hepatology: A Comparison with the Liver Damage and Child-Pugh Classifications. Liver Cancer 2017, 6, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.W.H.; Kumada, T.; Toyoda, H.; Tada, T.; Chong, C.C.N.; Mo, F.K.F.; Yeo, W.; Johnson, P.J.; Lai, P.B.S.; To, K.-F.; et al. Integration of albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score into Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 31, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, A.; Kumada, T.; Tsuji, K.; Takaguchi, K.; Itobayashi, E.; Kariyama, K.; Ochi, H.; Tajiri, K.; Hirooka, M.; Shimada, N.; et al. Validation of Modified ALBI Grade for More Detailed Assessment of Hepatic Function in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients: A Multicenter Analysis. Liver Cancer 2018, 8, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Tan, Y.; Tan, L.; Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Yan, L.; Wen, T. Albumin-Bilirubin Score for Predicting Post-Transplant Complications Following Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Ann. Transplant. 2018, 23, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronald, J.; Wang, Q.; Choi, S.; Suhocki, P.; Hall, M.; Smith, T.; Kim, C. Albumin-bilirubin grade versus MELD score for predicting survival after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) creation. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2018, 99, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Shim, S.G.; Sinn, D.H.; Song, J.E.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, H.G. Child-Pugh, MELD, MELD-Na, and ALBI scores: Which liver function models best predicts prognosis for HCC patient with ascites? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-J.; Zhang, Z.-G.; Zhu, P.; Mba’Nbo-Koumpa, A.-A.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.-P.; Shu, C.; Zhang, W.-G.; Feng, R.-J.; Li, G.-X. Comparative liver function models for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: A 10-year single center experience. Asian J. Surg. 2019, 42, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app10207178