Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) are a unique population of tumor cells that contribute to tumor growth, invasion, and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. These stem cells are capable of self-renewal and proliferation. The contributions of GSCs to tumor pathogenesis are mediated by a diverse repertoire of signaling pathways that influence GSC function and stemness. Molecules in these pathways may serve as the basis of anti-GSC targets.

- glioblastoma

- stem cell

- targeted therapy

- molecular pathway

1. Notch

Canonical Notch pathway receptors (Notch 1-4) are cell surface type 1 transmembrane receptors that mediate cell–cell signaling [71]. Notch ligands include delta-like 1, delta-like 3, delta-like 4, Jagged1, and Jagged2 [72]. The binding of ligands triggers the Notch receptors to undergo a series of successive γ-secretase-mediated proteolytic cleavage steps, liberating the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) [72]. Binding of the NICD to downstream transcriptional regulators in the nucleus allows Notch signaling to control expression of a broad range of target genes [72].

Analogously to other stem cell signaling molecules, Notch plays a key role in early embryogenesis, namely by preventing premature neurogenesis and maintaining pools of progenitor cells in the developing central nervous system (CNS) [14]. Notch signaling promotes human brain development by increasing progenitor cell proliferation and astrocyte differentiation [14]. In the adult brain, Notch inhibits neural stem cells (NSCs) apoptosis, promotes self-renewal, and suppresses differentiation, thereby maintaining a functional stem cell reserve in the CNS [14]. Similarly, the Notch pathway is crucial in promoting the survival of glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) in the tumor microenvironment, and regulates tumor initiation, progression, and recurrence [14,73]. Notch exhibits significant crosstalk with molecules in other signaling pathways, including the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and the hypoxic pathway [74]. It may also exert a role in GSC migration via upregulation of the CXCR4 chemokine [74]. However, the actual sequence of regulatory events and the precise mechanisms through which Notch activity controls stemness and tumorigenicity remain to be elucidated. While the complex role of Notch signaling in the brain remains to be clarified, over-activation of Notch signaling is at least partly responsible for GSC survival.

Computational analysis of largescale patient transcriptional datasets confirms that increased Notch activity correlates with negative clinical outcomes in glioma patients while also serving as a marker for GSC prevalence in tumor tissue [75]. In vitro modulation of Notch signaling further supports the idea that it plays a vital role in GSC vitality. In GSC neurosphere cultures, activation of Notch signaling enhances colony formation, increases self-renewal, and promotes de-differentiation [76]. Additionally, when both Notch and Wnt/β-catenin signaling are inhibited in cultured GSCs, neuronal differentiation is induced and clonogenic potential is inhibited [77]. Thus, targeting proteins involved in the Notch signaling pathway, including NICD, TRIM3, CXCR4, CXCL12, Hes, CPEB1, and Hey—several of which have been implicated in promoting either GSC stemness or differentiation—may be a viable strategy for promoting differentiation of GSCs and thereby sensitizing glioblastoma (GBM) tumors to therapeutic interventions [14]. However, it is important to note that these effects are only likely to be seen when high endogenous Notch activity can be confirmed in the targeted GSC population or tumor subtype [76].

2. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is often aberrantly expressed in GBM by amplification or mutation [78]. Increased activity of EGFR, either due to overexpression or the constitutive activity of its deletion variant, EGFRvIII, is associated with more aggressive disease [79]. Like Notch, EGFR plays a role in the maintenance of the NSC population in the CNS [78] and has also been shown to be necessary for the self-renewal capacity of GSCs in culture [80]. Inhibition of EGFR signaling using a tyrosine kinase inhibitor induces GSC differentiation and reduces the tumorigenicity and self-renewal potential of the treated cells [78]. These results indicate that EGFR signaling is necessary for the maintenance of GSCs in an undifferentiated state. Given these findings, anti-EGFR therapies have the potential to target GSCs and may represent a treatment possibility for patients with GBM. However, the GSC population is not homogenous. For instance, coexpression of the variant EGFRvIII, but not EGFR, with CD133 has been reported in GSCs [81]. Thus, any therapeutic interventions focused on signaling pathways must account for GSC heterogeneity.

One downstream signal transduction pathway for EGFR is the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTOR) survival cascade, which is also genetically altered in the vast majority of GBM tumors [11,82]. While this differential activation frames the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as a promising therapeutic target, in vivo and clinical application of PI3K pathway inhibitors has led to mixed results, possibly due to persistent mTOR signaling [83,84]. Additional studies investigating mTOR signaling escape mechanisms are warranted. Still, in vitro studies of patient derived GSCs indicate that PI3K inhibition reduces stem cell ability to proliferate and invade [85]. Downstream of PI3K, AKT signaling has been identified as a critical factor in the hyperthermia-induced radiosensitization of GSCs, with inhibition of PI3K enhancing these effects [86]. Due to pathway redundancy, it is almost certain that a combination of multiple inhibitors will be required to achieve an anti-GSC effect [87]. Moreover, inhibition of EGFR signaling in GSCs was shown to upregulate related family receptors, including eRBB2 and ERBB3, allowing the GSCs to resist the therapeutic treatment and survive [88]. Therefore, targeting both the EGFR pathway and ERBB family receptors may be necessary to achieve a vigorous anti-tumor response.

3. Sonic Hedgehog

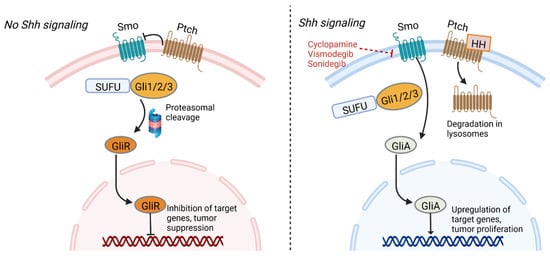

The sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway plays critical roles in normal embryonic development, neural tube patterning, the maintenance of adult stem cells, and tissue repair [89]. Activation of the pathway involves the sonic hedgehog ligand, the Patched (Ptch) transmembrane receptor, the Smoothened (Smo) transmembrane receptor, and glioma-associated oncogene (Gli) transcription factors. In the absence of hedgehog ligand, Ptch inhibits Smo, resulting in phosphorylation and proteolytic cleavage of the Gli protein into Gli repressor, which in turn binds gene promoters and inhibits their transcription. The binding of hedgehog ligand to the extracellular domain of Ptch results in their internalization and degradation in lysosomes, allowing for Smo to initiate a signaling cascade that allows formation of Gli activator, which then travels to the nucleus and promotes transcription of target genes (Figure 1) [90,91].

Figure 1. Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. In the absence of hedgehog ligand, Ptch inhibits Smo, resulting in formation of Gli repressor that inhibits target genes. Ptch and SUFU function as tumor suppressors. Hedgehog ligand’s interaction with Ptch results in its degradation, allowing a signaling cascade mediated by Smo that forms GliA. This transcription factor activates genes associated with tumor proliferation. Inhibitors of Smo represent a potential therapeutic target against GSCs. GliA—Gli activator, GliR—gli repressor, HH—hedgehog ligand, Ptch—Patched, Smo—smoothened, SUFU—Suppressor of fused homolog. Figure created with BioRender.com

Shh signaling plays an important regulatory role in cell renewal and cell cycle progression, and signaling components Ptch1, Gli1, and Gli2 are highly expressed in human stem cells and downregulated in differentiated cells [91,92]. Similarly, the pathway is involved in proliferation and self-renewal of cancer stem cells, and genetic expression profiling of GSCs has revealed Shh signaling-dependent pathways in some cell lineages [93,94]. For example, PTEN-expressing GBMs have been shown to contain higher levels of Shh and PTCH1 expression compared to GBMs lacking PTEN expression, and hyperactivity of the signaling pathway and GLI1 over-expression is associated with reduced survival time [91,94]. Inhibition of Shh signaling components could help reduce GBM cell viability. A mouse model using CD133+ GBM cells showed that inhibition of Shh can delay GBM growth and promote apoptosis, while mice overexpressing SHH displayed faster tumor growth [95]. Inhibition of Gli and Smo have also been shown to reduce tumor volume and size of neurospheres grown from GSCs [91,96]. Of note, synergism has been demonstrated using inhibitors against both the sonic hedgehog (SHH) and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, resulting in reduced GSC pluripotency [87].

4. Transforming Growth Factor Beta

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) is a cytokine involved in embryonic development, control of cell cycle and apoptosis, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and inflammatory processes [97,98]. As a homeostatic regulator, TGF-β plays a dual role functioning both as a tumor suppressor that promotes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, as well as an oncogenic factor that promotes cellular invasion and dedifferentiation when the signaling pathway becomes distorted or TGF-β is overexpressed [99,100,101]. TGF-β acts on serine/threonine kinase cell surface receptors, resulting in the assembly of two type I and two type II receptors in an activated heterotetrameric complex [102]. These receptors phosphorylate Smad family proteins, particularly Smad2 and Smad3, which assemble in trimeric complexes with Smad4 for translocation to the nucleus, where they regulate genetic expression [103]. A myriad array of non-Smad signaling pathways can also be activated by TGF-β [99].

Smad signaling induces leukemia inhibitory factor which acts via the JAK-STAT pathway to prevent differentiation and promote self-renewal of GSCs but not normal glial stem cells [104]. TGF-β signaling also acts on Sox4 to increase expression of Sox2, a stemness gene responsible for self-renewal. GBM cells around necrotic regions have been shown to express elevated levels of TGF-β along with stem cell markers such as CD133, suggesting that tissue hypoxia may promote TGF-β signaling which induces an epithelial-mesenchymal transition resulting in the stem cell phenotype [105]. In addition, TGF-β prevents proteasomal degradation of Sox9, a protein involved in migration and invasion of GBM cells [106]. Consequently, patients with GBM and high TGF-β/Smad activity tend to have aggressive tumors with a poor prognosis [107]. Inhibitors of TGF-β signaling have illustrated promise as a therapeutic target by promoting GSC differentiation and reducing proliferation [108]. Bone morphogenic proteins, included within the TGF-β family of proteins, also act to reduce the self-renewal capabilities of GSCs and promote their differentiation [14].

5. Wnt

The Wnt family of glycoproteins are involved in embryonic and neural stem cell development, cellular polarity, cell proliferation, and regulation of stemness [109,110]. In the absence of Wnt ligands, the protein adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) forms a cytoplasmic complex with other proteins that target β-catenin for destruction [111]. The binding of Wnt proteins to the frizzled receptor and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins on the cell surface initiates the signaling pathway, triggering either a canonical or non-canonical signaling cascade. The canonical pathway inhibits the destruction complex, resulting in stabilization of β-catenin, which travels to the nucleus and forms a complex with transcription factors to activate gene transcription. This pathway is involved in stem cell renewal, differentiation, and cellular proliferation [112]. Non-canonical pathways are β-catenin independent and regulate cytoskeletal structure and cell polarity through Rac and Rho GTPases or release of intracellular calcium [110]. Mutations in APC have been widely studied in cancer development, with loss of function of the inhibitory gatekeeper APC seen in nearly 80% of colorectal cancers [113]. Loss of APC also occurs in prostate, breast, gastric, and lung cancer [114]. APC mutations have also been reported in GBM, although their frequency is low, potentially indicating a smaller role for genetic mutations in GBM pathogenesis compared to other tumors [115,116].

Aberrant hyperactivation of the Wnt signaling pathway, whose causes can include mutations in APC, β-catenin, WTX, and TCF4, is implicated in tumor growth, recurrence, and self-renewal of GSCs [117]. The Wnt pathway has also been implicated in GBM resistance to TMZ and RT [118]. FoxM1, a nuclear transcription factor overexpressed in GBM, has been shown to form a complex with β-catenin allowing for accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus of tumor cells [116]. Overexpression of the oncogene PLAGL2 upregulates Wnt signaling molecules in the canonical pathway and enhances GSC self-renewal by regulating cellular differentiation [119]. In contrast, inhibition of WNT signaling and β-catenin can reduce GSC proliferation and suppress cell migration and invasion [110].

6. Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3

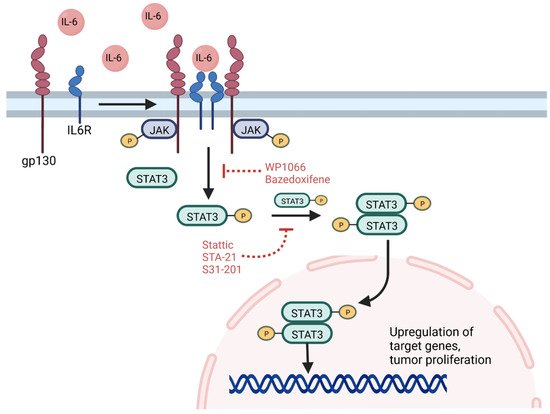

Activation and amplification of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) protein has been reported in nearly half of all human tumors and is associated with tumor proliferation, tumor survival, tissue invasion, and immunosuppression [120,121]. STAT3 functions as a signal transducer of cytokine pathways and a transcription factor that regulates expression of hundreds of genes, including oncogenes, and plays additional roles in epigenetic regulation and chromatin remodeling [121]. Canonical STAT3 signaling pathways feature ligand-induced dimerization of cytokine receptor, particularly the IL-6 receptor, which in turn phosphorylates the Janus family kinases (JAKs) [122]. These kinases phosphorylate tyrosine 705 of cytosolic STAT3, resulting in homodimerization and translocation to the nucleus where it serves as a regulator of gene expression (Figure 2) [123]. Other tyrosine kinases, including EGFR, can also phosphorylate STAT3 through similar pathways not initiated by IL-6 [123,124]. Post-translational modifications of STAT3 further influence its nuclear functions [121]. For example, phosphorylation of Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) results in STAT3 methylation, increasing STAT3 activity, and this interaction preferentially occurs in GSCs relative to other tumor cells [125]. The suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 protein normally acts to inhibit STAT3 signaling [122]. Recently, non-canonical pathways have been discovered, and some target genes can be activated by unphosphorylated STAT3, which also accumulates in response to IL-6 signaling [126].

Figure 2. STAT3 signaling pathway. The IL-6 cytokine triggers dimerization and activation of the IL6 receptor with its gp130 subunit. JAK phosphorylation in turn results in STAT3 phosphorylation, which dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus to upregulate target genes associated with stemness and GSC survival. Inhibition of the STAT3 pathway can be achieved at several points, including targeting of receptor signaling using WP1066 or bazedoxifene and inhibition of STAT3 dimerization and signaling using Stattic, STA-21, or S31-201. GP130—glycoprotein 130, IL6R—IL6 receptor, P—phosphorylation, STAT3—signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Figure created with BioRender.com

Constitutive activation of STAT3 has been detected in several cancer stem cells, including prostate, breast, and GBM, where it promotes a stem-cell phenotype and survival [127]. Hypoxic conditions can activate the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, driving GSC self-renewal [128]. A positive feedback loop in GSCs has also been discovered, in which Toll-like receptor 9, a molecule associated with tumor growth, drives activation of STAT3, which in turn upregulates expression of the Toll-like receptor [129]. The receptor is also activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and together with overexpression of the IL-6 receptor in GSCs, may indicate a role for inflammation in oncogenesis and GSC survival [121,127]. The glycoprotein CD109 can also activate the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in GSCs, contributing to GSC self-renewal and tumorigenicity, and depletion of CD109 was shown to impair stemness and contribute to a differentiated phenotype [130]. In addition, RT can promote phosphorylation of STAT3, which can contribute to tumor resistance to radiation. Conversely, inhibition of STAT3 has been shown to promote radiosensitivity in GBM cell lines [123,131].

STAT3 has emerged as a therapeutic target given its significant role in signaling and transcription pathways, although most work has been performed in vitro or in rodent models. Inhibition of STAT3 can affect growth and survival of GBM. Sherry et al. illustrated that inhibition of STAT3 using small molecule inhibitors or genetic knockdown using short hairpin RNA reduces GSC proliferation, neurosphere formation, and markers of GSC multipotency [132]. These results highlight the role of STAT3 in maintaining the phenotype of GSCs. Small molecular inhibitors of STAT3 have also been shown to induce apoptosis of GSCs [133].

7. Inhibitors of Differentiation

Basic helix-loop-helix proteins are transcription factors that form heterodimers and bind promoter and enhancer regions of genes, where they help regulate cell lineage and differentiation [134]. Inhibitors of differentiation (ID) proteins form dimers with basic helix-loop-helix proteins but cannot bind DNA as they lack basic moieties, thereby functioning as negative regulators of these transcription factors and instead serving to maintain the stem cell niche and self-renewal [135,136]. Consequently, ID proteins promote tumorigenesis and are upregulated in GBM, among other cancers, including breast and prostate cancer, where higher levels are associated with poorer prognosis [135,136,137,138,139].

One member of the ID family of proteins, ID-1, is situated at the nexus of multiple signal transduction pathways in GSCs. Cycloxygenase-2, overexpressed in GBM, can induce ID-1 expression via a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway that upregulates the early growth response protein 1 transcription factor [140]. The ID-1 protein can promote GSC self-renewal by inhibiting Cullin 3, a ubiquitin ligase normally responsible for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the DVL2 and GLI2 proteins. Suppression of Cullin 3 increases DVL2 and GLI2 levels, which in turn promote noncanonical ligand independent WNT and SHH signaling pathways that drive maintenance of GSCs [139]. Additional research has shown that ID-1-mediated WNT and SHH signaling can increase expression of the MYC proto-oncogene, whose functions include promoting transcription of miR-17 and miR-20a. These miRNAs inhibit expression of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor, a member of the TGF-β signaling pathway that promotes differentiation [141]. Downregulation of the receptor promotes resistance to differentiation signals from bone morphogenetic proteins, which normally initiate a signal transduction cascade after binding their type II receptor to promote transcription of target genes [141,142,143].

In addition to the Wnt, Shh, and TGF-β signaling pathways, research in other cancers has linked ID-1 to K-ras signaling, PI3K/Akt signaling, and STAT3 signaling, illustrating the centrality of ID-1 across multiple signaling pathways [134]. The influence of ID-1 on these pathways and activation of GSC self-renewal contributes to GSC resistance to chemotherapy and RT, worsening outcomes in patients with high expression of ID1 [134]. ID-1 can activate EGFR pathways that promote resistance to TMZ chemotherapy, resulting in tumor recurrence with ID-1-enriched cells after treatment [136]. EGFR can also induce a related ID protein, ID-3, which has also been shown to confer a stem cell phenotype to primary astrocytes [144]. Knockout of three genes of the ID family in mice with high-grade gliomas resulted in tumor regression and disruption of the interactions between GSCs and endothelial cells of the perivascular niche [145]. Therefore, therapeutics targeting ID-1 or related ID proteins may represent a potential novel treatment for GBM.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14153743

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!