2. Developments in the Photocatalyzed Production of Urea Using TiO2–Based Materials

Urea production by photocatalysis was first reported in 1998 by S. Kuwabata, H. Yamauchi, and H. Yoneyama

[9]. This research group presented the simultaneous reduction of CO

2 and nitrate ion (NO

3−) using titanium dioxide nanocrystals (Q–TiO

2) with sizes ranging from 1.0 to 7.5 nm, which were immobilized in a film of polyvinylpyrrolidone gel (Q–TiO

2/PVPD). A 500 W high–pressure mercury arc lamp was used as a light source for the experiments, in which wavelengths below 300 nm were removed with a glass filter.

S. Kuwabata et al.

[9] reported a concentration of about 1.9 mM urea in a 5 h photocatalysis using a Q–TiO2/PVPD film in polypropylene carbonate (PC) solutions saturated with CO

2 in the presence of LiNO

3 and using 2–Propanol as an electron donor species. However, when using Q–TiO

2 colloidal and TiO

2 P–25 colloidal, under the same conditions, they obtained an approximate concentration of 7.3 × 10

−2 mM and 3.3 × 10

−2 mM, respectively.

The results obtained by the Q–TiO

2/PVPD film were promising since a lower concentration of urea was expected as a product because of the belief that the use of the Q–TiO

2 photocatalyst particles fixed in a polymeric film reduces the area exposed to the solution as opposed to using suspended photocatalyst particles. S. Kuwabata et al.

[9] justified their results by studying the photo–oxidation of the urea formed, determining that urea and 2–propanol compete for active sites on the surface of Q–TiO

2, degrading and decreasing their concentration in the solution. According to research, using Q–TiO

2 in suspension increases the collision frequency and interaction between urea and the catalyst surface. The interface interaction generates a more significant reaction and increases the degradation of the already–formed products.

However, the concentration of the products formed by the urea degradation via photo–oxidation does not contribute directly to the secondary reactions leading to by–products such as methanol, ammonia, acetone, and hydrogen. The concentrations observed for the by–products remain proportional to urea formation, as shown in Table 1, whose results were obtained after photoreductions were made for 5 h.

Table 1. Amounts of products obtained by the photoinduced reduction of nitrate ions and carbon dioxide using different kinds of titanium dioxide photocatalysts. Adapted from S. Kuwabata et al.

[9].

| Catalyst |

Solvent |

Amount of Products (µmol) |

| Urea |

Acetone |

Methanol |

NH4+ |

H2 |

Ti3+ |

| Q–TiO2/PVPD |

PC |

5.6 |

61.0 |

1.2 |

2.7 |

0.18 |

0.14 |

| Q–TiO2 coloidal |

PC |

0.22 |

2.5 |

0.12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| P–25 TiO2/PVPD |

PC |

2.3 |

30.1 |

0.04 |

1.2 |

0.08 |

– |

| P–25 Coloidal |

PC |

0.1 |

1.1 |

0.05 |

0 |

0.06 |

– |

| P–25 TiO2/PVPD |

H2O |

0 |

0.07 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

– |

S. Kuwabata et al.

[9] used reduced species such as NH

2OH or NO

2, replicating the experimental conditions for the Q–TiO

2/PVPD film, reaching urea concentrations close to 5.6 and 2.9 mM, respectively, in 1 h. These results concluded that the limiting step of photocatalyzed urea production is the formation of reduced NO

3− ions species.

B.-J. Liu, T. Torimoto, and H. Yoneyama

[10] subsequently generated urea reaching concentrations of 3 mM using a film of TiO

2 nanocrystals embedded in SiO

2 matrices (Q–TiO

2/SiO

2). This experiment proposed the photochemical reduction of CO

2 saturated in a LiNO

3 solution, using 2–propanol as an electron donor. The system was irradiated for 5 h with a 500 W mercury arc lamp.

B.-J. Liu et al.

[10] reported that urea selectivity regarding other products, such as formate (HCO

2−) and carbon monoxide (CO), is influenced by the type of solvent used in the reaction and its dielectric constant (see

Table 2).

Table 2. Amount of product obtained by the photoinduced reduction reaction of lithium nitrate in solvents saturated with carbon dioxide. Adapted from T. Torimoto et al.

[11].

| Solvent |

Dielectric Constant,

ε |

Amount of Products (mM) (a) |

| Urea |

NH3 |

HCO2− |

CO |

| Ethylene glycol monoethyl ether |

29.6 |

1.00 |

0.20 |

0.80 |

0.50 |

| Acetonitrile |

37.5 |

1.15 |

0.15 |

0.70 |

0.20 |

| Sulfolane |

43.0 |

1.00 |

0.20 |

0.40 |

0.25 |

| PC |

69.0 |

0.85 |

0.25 |

0.10 |

0.05 |

| Water |

78.5 |

2.75 |

0.75 |

0.10 |

0.05 |

The results presented by B.-J. Liu et al.

[10] showed that the NO

3− ion reduction reaction is the determining step in producing urea and NH

3 as synthesis products. Urea and NH

3 concentrations increase by increasing the concentration of NO

3− as opposed to the concentration of HCO

2− that remained relatively constant. Similar results were presented by S. Kuwabata et al.

[9] using TiO

2 particles supported on a surface, justifying that the Q–TiO

2/SiO

2 film has a higher photocatalytic activity since the particles have a negative change in the edge of the conduction band caused by the effect of the quantization and the specific surface area estimated at 290 m

2 g

−1.

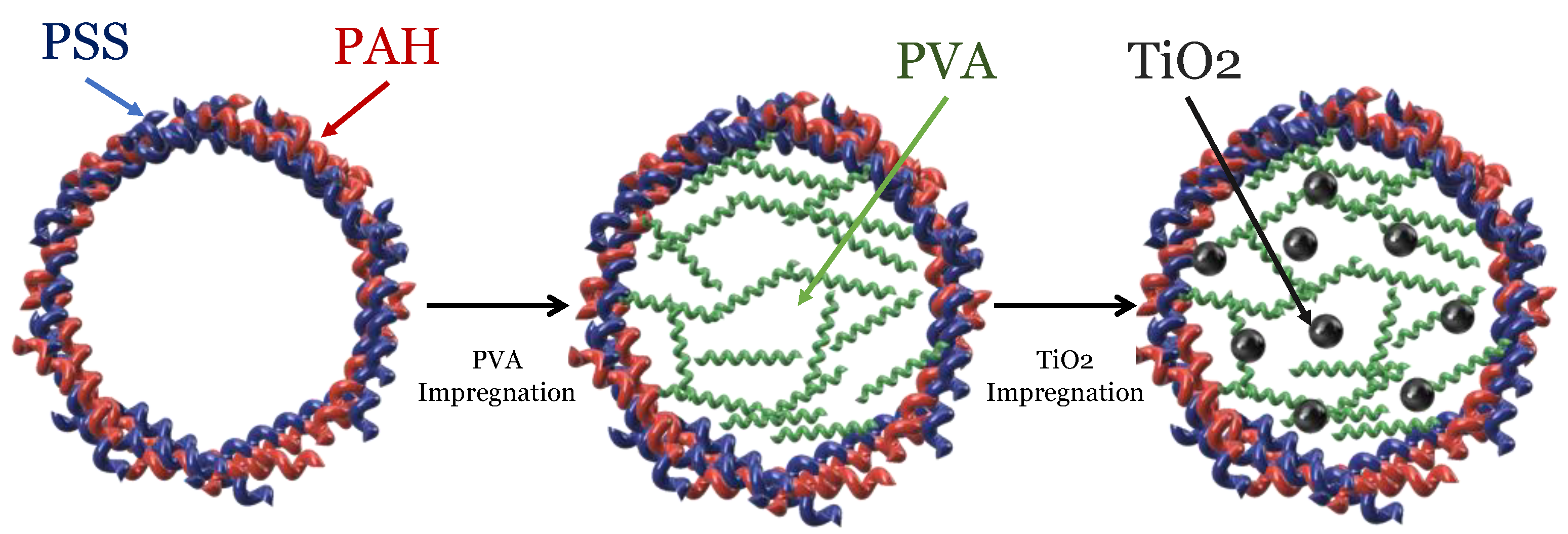

In 2005, a new proposal for the photochemical synthesis of urea arose at the hands of D.G. Shchukin and H. Möhwald

[12]. They proposed using microenvironments to synthesize complex compounds, allowing dimensions, structure, and morphology specificity. These microenvironments correspond to polyelectrolyte capsules, consisting of polyamine hydrochloride (PAH) and polystyrene sulfonate (PSS), which allow permeability to inorganic macromolecules and nanoparticles, depending on the solvent, pH, or ionic strength of the means. Under this methodology, it was possible to perform the photocatalyzed urea synthesis on TiO

2 nanoparticles, using CO

2 and NO

3− ions as a precursor, where polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fulfills the role of electron donor.

Figure 1 shows an assembly scheme for these spherical microreactors.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the photocatalytic spherical microreactor assembly. Adapted from D.G. Shchukin et al.

[12].

D.G. Shchukin and H. Möhwald

[12] reported a concentration close to 1.1 mM of urea, using spherical microreactors with a 2.2 μm diameter in an aqueous solution saturated with CO

2 in the presence of 0.1 M NaNO

3, followed by 5 h of irradiation with a 200 W Xg–He lamp. It was possible to observe a slight increase in urea concentration at 1.7 mM when incorporating copper (Cu) nanodeposits on TiO

2 particles. A simultaneous photocatalysis was expected both on the TiO

2 particles and on the surface of the Cu, which increased the reduction of the NO

3− to NH

4+ ions, considered the determining step for urea formation.

The results of D.G. Shchukin and H. Möhwald

[12] suggest that the main advantage of using microreactors is controlling reagents in the volume determined for the reaction. Furthermore, the confinement and the ability to control the input of substances give the possibility of modeling biochemical processes of living cells.

Later, E.A. Ustinovich et al.

[13] reported urea synthesis by the photoinduced reduction of CO

2 in the presence of NO

3− ions, using TiO

2 stabilized in perfluorodecalin (PFD:TiO

2) emulsions and 2–propanol as electron donor species. A 120 W high–pressure mercury vapor lamp was used as a light source. After one hour of irradiation, the concentration of urea was 0.54 mM and 1.1 mM using PFD:TiO

2 and PFD:TiO

2/Cu, respectively. The high efficiency and selectivity observed in urea formation, as observed in

Table 3, are attributed to a high concentration of CO

2 in the oleic phase, granting favorable conditions to stabilize intermediary species, allowing the formation of C–N bonds

[14].

Table 3. Photoproduction ratio of urea and formate from 0.1 M NaNO

3 solution with CO

2 saturated using different TiO

2 photocatalysts. Adapted from E.A. Ustinovich et al.

[13].

| Catalyst |

Amount of Products (mMh) (a) |

Urea–Formate Ratio |

| Urea |

Formate |

| TiO2 |

0.28 |

0.11 |

2.5 |

| TiO2/Cu |

0.40 |

0.050 |

8.0 |

| PFD:TiO2 |

0.58 |

0.15 |

3.9 |

| PFD:TiO2/Cu |

1.12 |

0.025 |

45 |

E.A. Ustinovich et al.

[13] demonstrated that PFD emulsions could dissolve a considerable amount of O

2 and CO

2, 45 mL/100 mL and 134 mL/100 mL, respectively, which usually demand high pressures. This methodology allowed the accumulation of different organic compounds, whether substrates, intermediates, or products, favoring light–induced reactions.

It is important to note that E.A. Ustinovich et al.

[13] established that using concentrations higher than 1.0 M NaNO

3 as a source of N does not significantly increase urea concentration. Hence, this concentration is the saturation limit value of NaNO

3 for solutions used in photocatalyzed urea production.

One of the latest publications on photocatalyzed urea production using TiO

2 was presented by B. Srinivas et al.

[15]. The research group studied urea synthesis using KNO

3 solutions as a source of N in the presence of 2–propanol or oxalic acid as electron donor, producing CO

2 in–situ as a reaction product. After 6 h of UV irradiation, using a 250 W high–pressure mercury lamp, it was possible to obtain urea concentrations close to 0.20, 0.10, and 0.31 mM, using TiO

2, iron titanate (Fe

2TiO

5), and iron titanate supported on proton exchange zeolite Socony Mobil–5 (Fe

2TiO

5/HZSM–5) as a photocatalyst, respectively.

B. Srinivas et al.

[15] showed that using iron titanates supported in HZSM–5 promotes the separation of photoinduced charges, enhancing urea selectivity. Additionally, zeolites presented high adsorption of CO

2 and NH

3, which, according to the research, was produced in–situ on the catalyst surface. The condensation for urea formation is facilitated by the adsorption property in the zeolite that inhibits the polymerization of the products.

In a recent report by H. Maimaiti et al.

[16], the photocatalyzed synthesis of urea was performed on carbon nanotubes (CNTs) with Fe/Ti

3+–TiO

2 composite as catalyst (Ti

3+–TiO

2/Fe–CNTs). This research group has established that urea synthesis from the simultaneous reduction of N

2 and CO

2 in H

2O is related to the arrangement of Ti

3+ sites and oxygen vacancies on the catalyst surface. The Ti

3+ sites act as the active center of N

2 and oxygen vacancies acts as the active center for CO

2 on the Ti

3+–TiO

2 surface. H. Maimaiti et al.

[16] state that urea formation is achieved by adsorption and activation, converting the N

2 and CO

2 molecules into a cyclic intermediate that is transformed into two urea molecules. This research reports a urea yield of 710.1

μmol L

−1 g

−1 after 4 h of reaction using a 300 W high–pressure mercury lamp as the light source.

Although the trend indicates the use of photocatalysts fixed on a surface which enables better control over the reaction solution, and then the separation of the catalyst from the reaction solution, H. Maimaiti et al.

[16] propose using a catalyst supported on CNTs to improve the dispersion in water. However, the catalysts used have an Fe core, which allows their rapid and simple separation from the reaction solution using an external magnetic field.

Table 4 summarizes the highest urea concentration obtained by each reported work, according to the experimental set–up proposed by each author mentioned above. Since the photocatalyzed urea syntheses were performed under different experimental conditions, a direct comparison of the results obtained is limited. Table 4 shows the urea concentration normalized by the irradiation time used in each work. The reaction yields or quantum yields could not be considered for comparing results because these data were not reported in most of the works studied.

Table 4. Amount of urea synthesized by photocatalysis.

| Author |

Catalyst |

C Source |

N Source |

Solvent |

Illumination Time, h |

Urea,

mM |

Urea,

mM h−1 |

| S. Kuwabata et al. [9] |

Q–TiO2/PVPD |

CO2, sat. |

NH2OH

0.020 M (a) |

PC |

1 |

5.7 (a,c) |

5.7 |

| B.-J. Liu et al. [10] |

Q–TiO2/SiO2 |

CO2, sat. |

LiNO3

0.020 M |

H2O |

5 |

2.75 (b) |

0.55 |

| D.G. Shchukin et al. [12] |

Cu/TiO2–PVA–PAH/PSS

(2.2 μm diameter) |

CO2, sat. |

NaNO3

0.1 M |

H2O |

5 |

1.72 (c) |

0.34 |

| E.A. Ustinovich et al. [13] |

Cu/TiO2:PFD |

CO2, sat. |

NaNO3

1.0 M |

PDF:H2O |

1 |

1.1 (c,d) |

1.1 |

| B. Srinivas et al. [15] |

Fe2TiO5(10wt%)/HZSM–5 |

2–propanol

1 v/v% |

KNO3

0.016 M |

H2O |

6 |

0.31 (e) |

0.052 |

| H. Maimaiti et al. [16] |

Ti3+–TiO2/Fe–CNTs |

CO2 (100 mL min−1 flow rate) |

N2 (100 mL min−1 flow rate) |

H2O |

4 |

0.710 (f) |

0.178 |

When urea concentration is normalized by hours of irradiation, it is possible to observe how the solution or support used plays an essential role in stabilizing the reagents and intermediate species. For example, PFD emulsions allow the dissolving of high concentrations of gaseous substrates at room pressure, increasing the availability of CO

2, favoring urea formation, and stabilizing TiO

2 particles. Moreover, using reduced species such as NO or NH

2OH as a nitrogen source favors the generation of intermediate species, modifying selectivity by by–products, as S. Kuwabata et al.

[9] reported.

Contrary to what was thought, using supported TiO2 particles, in some cases, favors urea synthesis. Modifying the size of the supported particles allows changing the semiconductor band–gap. It should be considered that reactions on supported catalysts are governed by diffusion phenomena and can be controlled more easily. In addition, the use of support surfaces makes it possible to avoid particle aggregation in solution, reduce irradiation shielding, and prevent reactions depending on particle collision phenomena, allowing, in turn, better adsorption and even increasing the spatial selectivity of reactants and products.

The above is critical in scaling these technologies because separating and recovering a suspended catalyst from an aqueous solution using filtration systems or more complex unit operations could increase production costs. The use of catalysts with magnetic properties that could be removed from the reaction solution by applying a magnetic field is a possible solution for the use of suspension catalysts.

The confinement of the reaction space in low–scale photoreactors such as microcapsules or microreactors allows the control of the diffusion, input, or output flow of reactants and products and the specificity of the synthesis, stereochemistry, and functionalization of the products formed. The spherical microreactors evaluated produce lower mobility of the compounds, enhancing the interaction between the reactant species and the photocatalyst particles and increasing the concentration of the desired products.

A constant flow of the gases used as a source of C and N is a relevant factor. Considering the low solubility of gases in aqueous media and the time necessary to perform the photocatalytic reduction studied, a high and constant concentration of C and N sources is required to optimize the urea production flow.

Even though each experimental set–up proposed has an improvement or an innovation to the photocatalysis technology, there are still many edges to explore in urea synthesis photocatalyzed by TiO2–based materials.