Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is becoming increasingly prevalent and currently affects approximately 14.3% of the adult US population. Moreover, a further 38.0% of the adult US population has prediabetes, i.e., impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetic neuropathy is a frequent complication of both T2DM and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), and it is present in approximately 3.5–9.4% of patients who havehad T1DM for 1–5 years and in 28% of patients who havehad T2DM for > 4 –7 years. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are the antihypertensive agents of choice for hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus (along with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ACE-I). ARBs act by inhibiting the binding of angiotensin II (which is produced by the cleavage of angiotensin I by the angiotensin-converting enzyme) to angiotensin receptor I, thereby promoting vasodilation and inhibiting aldosterone secretion.

1. Preclinical Studies

In an early study ofstreptozotocin-diabetic rats, the ARB ZD 8731 was given 1 month after the induction of diabetes and for a duration of 1 month [

28]. ZD 8731 ameliorated both motor and sensory nerve conduction velocity (NCV) [

28]. An increase in nerve capillary density was observed, which might have contributed to the improvement in NCV [

28]. In contrast, ZD 8731 had no effect on these parameters in non-diabetic rats [

28]. The same group of investigators assessed the effects of another ARB, ZD 7155, in streptozotocin-diabetic rats [

29]. ZD 7155 was given for 1 month, either immediately after the induction of diabetes or after 1 month [

29]. The amelioration of motor and sensory NCV and an improvement in nerve regeneration after experimental damage were observed regardless of the timing of treatment initiation [

29]. The investigators confirmed an ARB-induced increase in nerve capillary density and also observed an augmentation of endoneurial blood flow [

29]. In another study, olmesartan improved nerve regeneration in diabetic rats [

29]. There was an increase in the production of the ciliary neurotrophic factor (a nerve growth factor), which might have played a role in this neurotrophic effect [

30]. Interestingly, in vitro and animal studies have also reported the neurotrophic effect of olmesartan on spinal motor neurons in non-diabetic animals [

31].In an in vitro study ofPC12 cells, both losartan and telmisartan reduced oxidative stress, but only telmisartan prevented glucose-induced apoptosis [

32]. In more recent studies, both losartan and telmisartan prevented the development of neuropathy in diabetic rat models [

33,

34].

2. Clinical Studies

In contrast to these promising experimental data, early clinical studies that assessed the effects of ARBs on diabetic neuropathy yielded negative results [

35,

36]. In normotensive patients with T2DM and microalbuminuria, treatment with losartan for 12 weeks did not improve peripheral or autonomic neuropathy [

35]. In another early study onpatients with T1DM or T2DM, treatment with losartan for 12 months did not improve cardiovascular autonomic function or the vibration-perception threshold [

36]. However, in another study, treatment with losartan for 12 months improved autonomic nervous function in normotensive patients with autonomic neuropathy due to either T1DM or T2DM [

37]. Treatment with quinapril also ameliorated autonomic neuropathy, in accordance with previous findings [

38,

39]. Interestingly, the losartan/quinapril combination appeared to be more beneficial than either monotherapy [

37]. However, the vibration-perception threshold did not change with either losartan or quinapril [

37]. These findings, although preliminary, suggest that the beneficial effectsof ARB on diabetic neuropathy become apparent only after long-term treatment, and that autonomic neuropathy improves more with these agents than peripheral neuropathy [

37]. However, a study onhypertensive patients with diabetic nephropathy showed an improvement in the low-tohigh-frequency ratio (an index of sympathovagal balance) after only 12 weeks of treatment with losartan or telmisartan [

40].

3. ARBs and Erectile Dysfunction

Diabetic neuropathy might also manifest as erectile dysfunction, which is present in approximately 60% of patients who have had T1DM or T2DM for > 10–20 years [

62,

63]. Studies onstreptozotocin-diabetic rats and aged rats showed an improvement in erectile function with ARB treatment [

64,

65,

66]. ARBs also ameliorated erectile dysfunction in hypertensive patients with [

67] or without the metabolic syndrome, which is a prediabetic condition [

68,

69]. However, it has not been evaluated whether ARBs improve erectile function in diabetic patients.

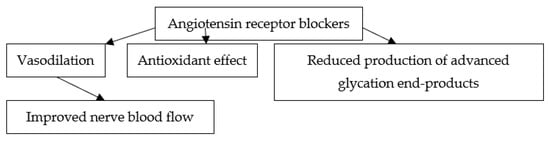

4. Putative Mechanisms of the Effects of ARBs on Diabetic Neuropathy

Several mechanisms appear to account for the beneficial effects of ARBs on diabetic neuropathy. ARBs might confer neuroprotection by improving nerve blood flow through their vasodilating properties [

70]. Interestingly, in animal models of diabetic neuropathy, angiotensin II reduced endoneurial blood flow more than in non-diabetic animals [

71]. Oxidative stress and advanced glycation end-products also appear to play a role in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy [

72,

73]. On the other hand, ARBs exert antioxidant effects [

74,

75] and reduce the production of advanced glycation end-products [

76]. Accordingly, it was suggested that these actions might play a role in the neuroprotective effects of ARBs [

77]. Several prospective studies showed that hypertension increases the risk ofneuropathy in diabetic patients [

8,

9]. However, in several randomized controlled trials involving patients with T2DM, more aggressive antihypertensive treatment did not prevent or delay the progression of neuropathy as compared with less tight blood pressure control [

78,

79,

80,

81]. Nevertheless, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and ACE-Is were used in the latter trials, and it remains to be established whether ARBs can improve diabetic neuropathy independently of their blood pressure-lowering effects. Regarding erectile function, the beneficial effects of ARBs are partly due to the inhibition of angiotensin II, which is locally produced in the corpus cavernosum and directly terminates erection [

82,

83,

84]. ARBs also improved erectile function through the suppression of oxidative stress and an increase in the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the corpus cavernosum [

64]. Whether the improvement in diabetic neuropathy plays a role in the amelioration of erectile dysfunction during ARB treatment remains to be established.The major mechanisms potentially implicated in the beneficial effects of ARBs on diabetic neuropathy are shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Major mechanisms potentially implicated in the beneficial effects of angiotensin receptor blockers on diabetic neuropathy.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jpm12081253