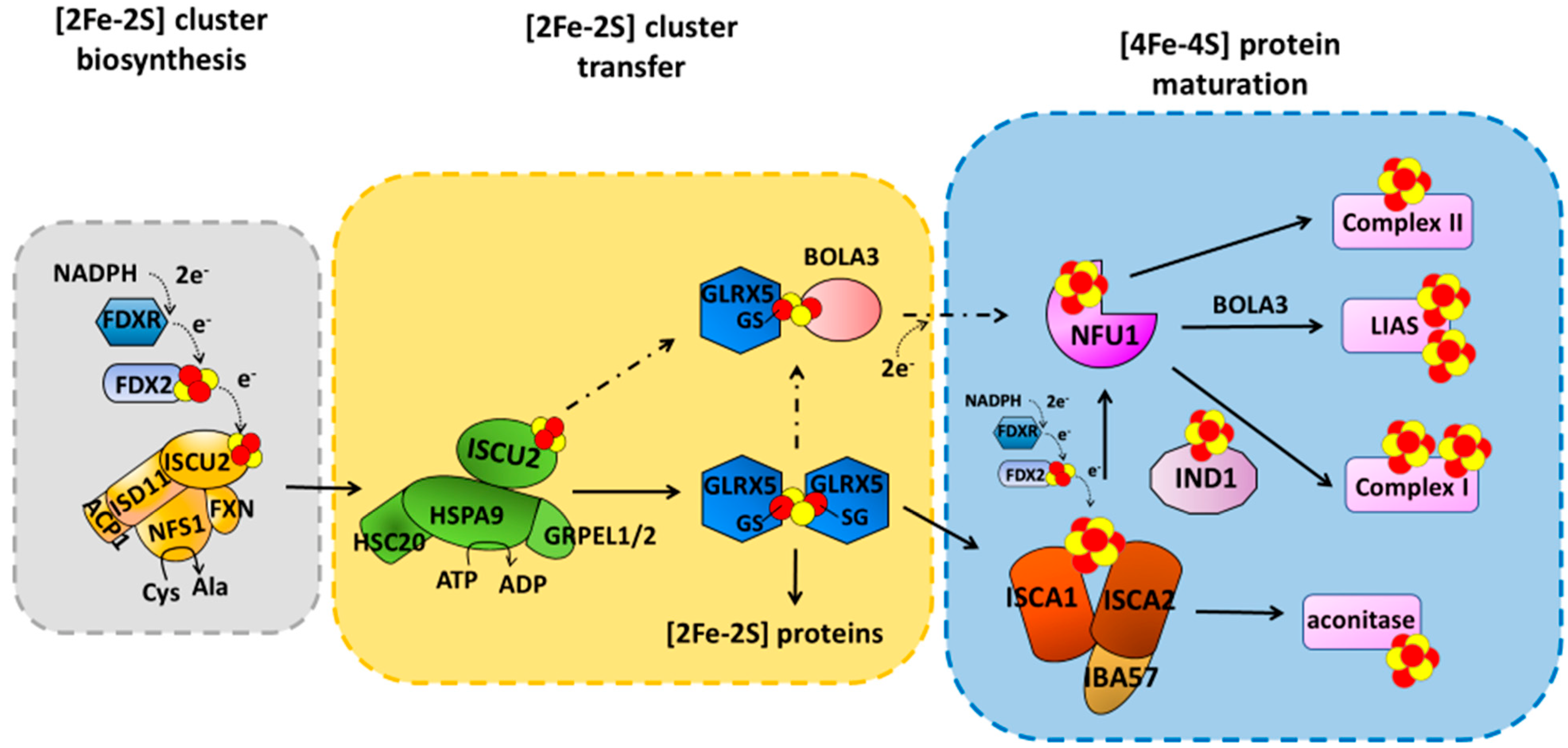

The importance of mitochondria in mammalian cells is widely known. Several biochemical reactions and pathways take place within mitochondria: among them, there are those involving the biogenesis of the iron–sulfur (Fe-S) clusters. The latter are evolutionarily conserved, ubiquitous inorganic cofactors, performing a variety of functions, such as electron transport, enzymatic catalysis, DNA maintenance, and gene expression regulation. The synthesis and distribution of Fe-S clusters are strictly controlled cellular processes that involve several mitochondrial proteins that specifically interact each other to form a complex machinery (Iron Sulfur Cluster assembly machinery, ISC machinery hereafter). This machinery ensures the correct assembly of both [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters and their insertion in the mitochondrial target proteins.

- iron–sulfur cluster

- mitochondrial proteins

- multiple mitochondrial dysfunction syndromes

- rare diseases

1. Introduction

2. [4Fe-4S] Cluster Assembly in Mitochondria

3. Mutations on Components Maturing ISC Proteins Cause Severe Congenital Diseases

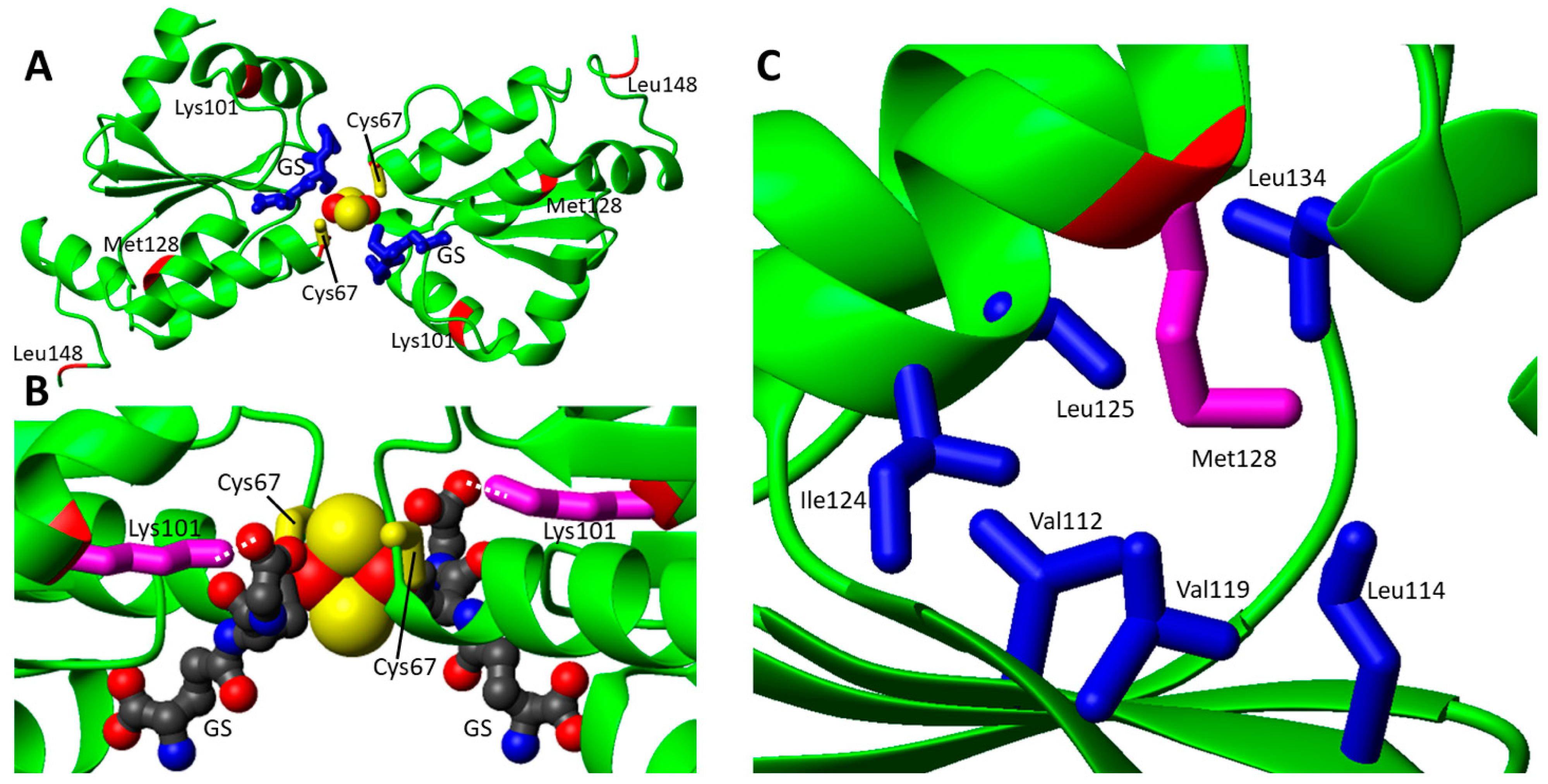

3.1. Structural Aspects of Pathogenic Missense Mutations in GLRX5, a Protein Involved in a Rare Form of Congenital Sideroblastic Anemia

| Gene/ Protein |

Missense Mutation | Predicted Protein Mutations | Associated Disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLRX5 | c.301A > C; c.443T > C | p.Lys101Gln; p.Leu148Ser | Nonsindromic sideroblastic anemia 3 | [51] |

| c.200G > A; c.383T > A | p.Cys67Tyr; p.Met128Lys | Nonsindromic sideroblastic anemia 3 | [52] | |

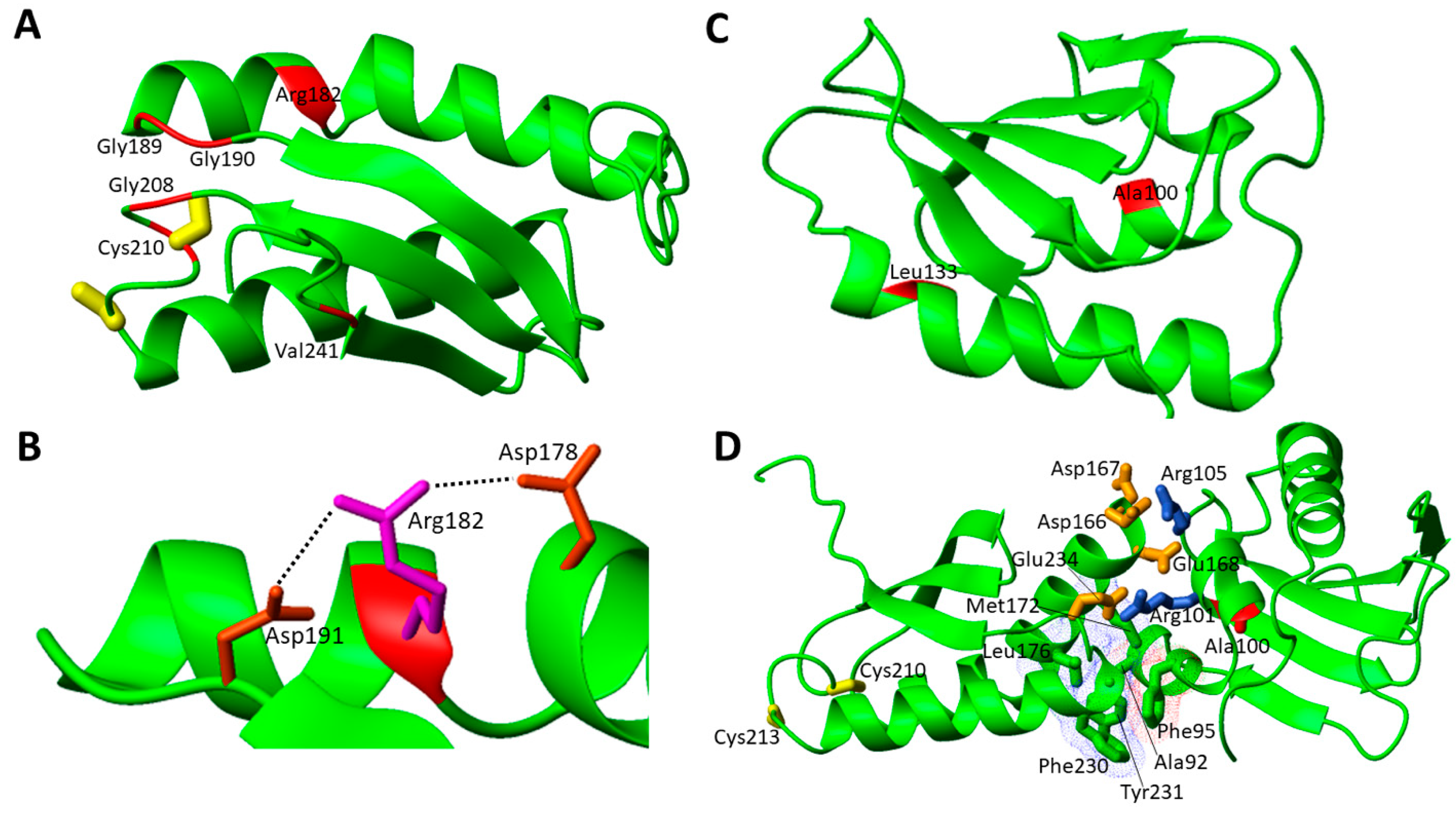

| NFU1 | c.545G > A; c.545G > A | p.Arg182Gln; p.Arg182Gln | MMDS1 | [43] |

| c.622G > T; c.622G > T | p.Gly208Cys; p.Gly208Cys | MMDS1 | [53][54] | |

| c.565G > A; c.565G > A | p.Gly189Arg; p.Gly189Arg | MMDS1 | [55] | |

| c.179G > T; c.179G > T | p.Phe60Cys; p.Phe60Cys | MMDS1 | [56] | |

| c.545G > A; c.622G > T | p.Arg182Gln; p.Gly208Cys | MMDS1 | [57] | |

| c.544C > T; c.622G > T | p.Arg182Trp; p.Gly208Cys | MMDS1 | [58] | |

| c.629G > T; c.622G > T | p.Cys210Phe; p.Gly208Cys | MMDS1 | [56] | |

| c.565G > A; c.622G> T | p.Gly189Arg; p.Gly208Cys | MMDS1 | [56][59] | |

| c.565G > A; c.629G > T | p.Gly189Arg; p.Cys210Phe | MMDS1 | [60] | |

| c.565G > A; c.568G > A | p.Gly189Arg; p.Gly190Arg | MMDS1 | [61] | |

| c.62G > C; c.622G > T | p.Arg21Pro; p.Gly208Cys | MMDS1 | [61] | |

| c.299C > G; c.398T > C | p.Ala100Gly; p.Leu133Pro | MMDS1 | [62] | |

| c.721G > T; c.303_369del | p.Val241Phe; ? | MMDS1 | [63] | |

| BOLA3 | c.200T > A; c.200T > A | p.Ile67Asn; p.Ile67Asn | MMDS2 | [64][65] |

| c.287A > G; c.287A > G | p.His96Arg; p.His96Arg | MMDS2 | [66][67][68] | |

| c.295C > T; c.295C > T | p.Arg99Trp; p.Arg99Trp | MMDS2 | [69] | |

| c.176G > A; c.136C > T | p.Cys59Tyr; p.Arg46 *a | MMDS2 | [70] | |

| IBA57 | c.706C > T; c.706C > T | p.Pro236Ser; p.Pro236Ser | MMDS3 | [71] |

| c.941A > C; c.941A > C | p.Gln314Pro; p.Gln314Pro | MMDS3 | [72] | |

| c.286T > C; c.188G > A | p.Tyr96His; p.Gly63Asp | MMDS3 | [73][74] | |

| c.316A > G; c.286T > C | p.Thr106Ala; p.Tyr96His | MMDS3 | [73][74] | |

| c.738C > G; c.316A > G | p.Asn246Lys; p.Thr106Ala | MMDS3 | [56] | |

| c.757G > C; c.316A > G | p.Val253Leu; p.Thr106Ala | MMDS3 | [56] | |

| c.335T > G; p.437G > C | p.Leu112Trp; p.Arg146Pro | MMDS3 | [56] | |

| c.335T > C; c.588dup | p.Leu112Ser; p.Arg197Alafs | MMDS3 | [75] | |

| c.386A > T; c.731A > C | p.Asp129Val; p.Glu244Ala | MMDS3 | [76] | |

| c.436C > T; c.436C > T | p.Arg146Trp; p.Arg146Trp | MMDS3 | [77] | |

| c.586T > G;c.686C > T | p.Trp196Gly; p.Pro229Leu | MMDS3 | [71] | |

| c.656 > G; c.706C > T | p.Tyr219Cys; p.Pro236Ser | MMDS3 | [69] | |

| c.701A > G; c.782T > C | p.Asp234Gly; p.Ile261Thr | MMDS3 | [73][74] | |

| c.738C > G; c.802C > T | p.Asn246Lys; p.Arg268Cys | MMDS3 | [69] | |

| c.286T > C; c.754G > T | p.Tyr96His; p.Gly252Cys | MMDS3 | [73][74] | |

| c.323A > C; c.150C > A | p.Tyr108Ser; pCys50 *a | MMDS3 | [76] | |

| c.87insGCCCAAGGTGC; c.313C > T | p.Arg30Alafs; p.Arg105Trp | MMDS3 | [71] | |

| c.236C > T; c.307C > T | p.Pro79Leu; p.Gln103 *a | MMDS3 | [74] | |

| c.580A > G; c.286T > C | p.Met194Val; p.Tyr96His | MMDS3 | [78] | |

| ISCA2 | c.154C > T; c.154C > T | p.Leu52Phe; p.Leu52Phe | MMDS4 | [56] |

| c.313A > G; c.313A > G | p.Arg105Gly; p.Arg105Gly | MMDS4 | [56] | |

| c.G229 > A; c.G229 > A | p.Gly77Ser; p.Gly77Ser | MMDS4 | [79][80][81] | |

| c.355G > A; c.355G > A | p.Ala119Thr; p.Ala119Thr | MMDS4 | [82] | |

| c.5C > A; c.413C > G | p.Ala2Asp; p.Pro138Arg | MMDS4 | [83] | |

| c.295delT; c.334A > G | p.Phe99Leufs*18; b p.Ser112Gly | [84] | ||

| ISCA1 | c.259G > A; c.259G > A | p.Glu87Lys; p.Glu87Lys | MMDS5 | [85][86] |

| c.29T > G; c.29T > G | p.Val10Gly; p.Val10Gly | MMDS5 | [87] | |

| c.302A > G; c.302A > G | p.Tyr101Cys; p.Tyr101Cys | MMDS5 | [88] | |

| IND1 | c.815-27T > C; c.G166 > A | p.Asp273Glnfs*31; b p.Gly56Arg | Complex I deficiency | [89][90][91] |

| c.313G > T; c.166G > A; c.815-27T > C | p.Asp105Tyr; p.Gly56Arg; p.Asp273Glnfs*31 b | Complex I deficiency | [89][90][91] | |

| c.579A > C; c.G166 > A | p.Leu193Phe; p.Gly56Arg | Complex I deficiency | [89][90][91] | |

| c.311T > C; c.815-27T > C | p.Leu104Pro; p.Asp273Glnfs*31 b | Complex I deficiency | [92] | |

| c.815-27T > C; c.545T > C | p.Val182Ala; p.Val182Ala | Complex I deficiency | [92] | |

| FDX2 | c.1A > T; c.1A > T | p.Met1Leu; p.Met1Leu | MEOAL | [93] |

| c.431C > T; c.431C > T | p.Pro144Leu; p.Pro144Leu | MEOAL | [94] |

3.2. Pathogenic Missense Mutations in the Late Acting Accessory Proteins of the ISC Machinery

3.2.1. Structural Aspects of Pathogenic Missense Mutations of NFU1 Involved in MMDS1

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12071009

References

- Johannsen, D.L.; Ravussin, E. The Role of Mitochondria in Health and Disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2009, 9, 780–786.

- Friedman, J.R.; Nunnari, J. Mitochondrial Form and Function. Nature 2014, 505, 335–343.

- Lill, R. Function and Biogenesis of Iron-Sulphur Proteins. Nature 2009, 460, 831–838.

- Rouault, T.A. The Indispensable Role of Mammalian Iron Sulfur Proteins in Function and Regulation of Multiple Diverse Metabolic Pathways. Biometals 2019, 32, 343–353.

- Beinert, H. Iron-Sulfur Proteins: Ancient Structures, Still Full of Surprises. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 5, 2–15.

- Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Nasta, V.; Banci, L. Protein Networks in the Maturation of Human Iron–Sulfur Proteins. Metallomics 2018, 10, 49–72.

- Lill, R.; Dutkiewicz, R.; Freibert, S.A.; Heidenreich, T.; Mascarenhas, J.; Netz, D.J.; Paul, V.D.; Pierik, A.J.; Richter, N.; Stümpfig, M.; et al. The Role of Mitochondria and the CIA Machinery in the Maturation of Cytosolic and Nuclear Iron-Sulfur Proteins. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 94, 280–291.

- Braymer, J.J.; Lill, R. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis and Trafficking in Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 12754–12763.

- Maio, N.; Jain, A.; Rouault, T.A. Mammalian Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis: Recent Insights into the Roles of Frataxin, Acyl Carrier Protein and ATPase-Mediated Transfer to Recipient Proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 55, 34–44.

- Boniecki, M.T.; Freibert, S.A.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Lill, R.; Cygler, M. Structure and Functional Dynamics of the Mitochondrial Fe/S Cluster Synthesis Complex. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1287.

- Cory, S.A.; Van Vranken, J.G.; Brignole, E.J.; Patra, S.; Winge, D.R.; Drennan, C.L.; Rutter, J.; Barondeau, D.P. Structure of Human Fe-S Assembly Subcomplex Reveals Unexpected Cysteine Desulfurase Architecture and Acyl-ACP-ISD11 Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E5325–E5334.

- Patra, S.; Barondeau, D.P. Mechanism of Activation of the Human Cysteine Desulfurase Complex by Frataxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19421–19430.

- Van Vranken, J.G.; Jeong, M.-Y.; Wei, P.; Chen, Y.-C.; Gygi, S.P.; Winge, D.R.; Rutter, J. The Mitochondrial Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP) Coordinates Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Synthesis with Iron Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis. Elife 2016, 5, e17828.

- Adam, A.C.; Bornhövd, C.; Prokisch, H.; Neupert, W.; Hell, K. The Nfs1 Interacting Protein Isd11 Has an Essential Role in Fe/S Cluster Biogenesis in Mitochondria. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 174–183.

- Wiedemann, N.; Urzica, E.; Guiard, B.; Müller, H.; Lohaus, C.; Meyer, H.E.; Ryan, M.T.; Meisinger, C.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Lill, R.; et al. Essential Role of Isd11 in Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Cluster Synthesis on Isu Scaffold Proteins. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 184–195.

- Sheftel, A.D.; Stehling, O.; Pierik, A.J.; Elsässer, H.-P.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Webert, H.; Hobler, A.; Hannemann, F.; Bernhardt, R.; Lill, R. Humans Possess Two Mitochondrial Ferredoxins, Fdx1 and Fdx2, with Distinct Roles in Steroidogenesis, Heme, and Fe/S Cluster Biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11775–11780.

- Cai, K.; Tonelli, M.; Frederick, R.O.; Markley, J.L. Human Mitochondrial Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) and Ferredoxin 2 (FDX2) Both Bind Cysteine Desulfurase and Donate Electrons for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 487–499.

- Gervason, S.; Larkem, D.; Mansour, A.B.; Botzanowski, T.; Müller, C.S.; Pecqueur, L.; Le Pavec, G.; Delaunay-Moisan, A.; Brun, O.; Agramunt, J.; et al. Physiologically Relevant Reconstitution of Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis Uncovers Persulfide-Processing Functions of Ferredoxin-2 and Frataxin. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3566.

- Dutkiewicz, R.; Nowak, M. Molecular Chaperones Involved in Mitochondrial Iron–Sulfur Protein Biogenesis. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 23, 569–579.

- Sen, S.; Rao, B.; Wachnowsky, C.; Cowan, J.A. Cluster Exchange Reactivity of Cluster-Bridged Complexes of BOLA3 with Monothiol Glutaredoxins. Metallomics 2018, 10, 1282–1290.

- Brancaccio, D.; Gallo, A.; Mikolajczyk, M.; Zovo, K.; Palumaa, P.; Novellino, E.; Piccioli, M.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. Formation of Clusters in the Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Machinery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16240–16250.

- Banci, L.; Brancaccio, D.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Del Conte, R.; Gadepalli, R.; Mikolajczyk, M.; Neri, S.; Piccioli, M.; Winkelmann, J. Cluster Transfer in Iron-Sulfur Protein Biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6203–6208.

- Lebigot, E.; Schiff, M.; Golinelli-Cohen, M.-P. A Review of Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunction Syndromes, Syndromes Associated with Defective Fe-S Protein Maturation. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 989.

- Camaschella, C. Recent Advances in the Understanding of Inherited Sideroblastic Anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 143, 27–38.

- Jain, A.; Singh, A.; Maio, N.; Rouault, T.A. Assembly of the Cluster of NFU1 Requires the Coordinated Donation of Two Clusters from the Scaffold Proteins, ISCU2 and ISCA1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020, 29, 3165–3182.

- Brancaccio, D.; Gallo, A.; Piccioli, M.; Novellino, E.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. Cluster Assembly in Mitochondria and Its Impairment by Copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 719–730.

- Weiler, B.D.; Brück, M.-C.; Kothe, I.; Bill, E.; Lill, R.; Mühlenhoff, U. Mitochondrial Protein Assembly Involves Reductive Cluster Fusion on ISCA1-ISCA2 by Electron Flow from Ferredoxin FDX2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 20555–20565.

- Gourdoupis, S.; Nasta, V.; Calderone, V.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. IBA57 Recruits ISCA2 to Form a Cluster-Mediated Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14401–14412.

- Nasta, V.; Da Vela, S.; Gourdoupis, S.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Svergun, D.I.; Banci, L. Structural Properties of ISCA2-IBA57: A Complex of the Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Machinery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18986.

- Stehling, O.; Wilbrecht, C.; Lill, R. Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Protein Biogenesis and Human Disease. Biochimie 2014, 100, 61–77.

- Maio, N.; Rouault, T.A. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis in Mammalian Cells: New Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms of Cluster Delivery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 1493–1512.

- Saudino, G.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. Protein-Interaction Affinity Gradient Drives Cluster Insertion in Human Lipoyl Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5713–5717.

- Suraci, D.; Saudino, G.; Nasta, V.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. ISCA1 Orchestrates ISCA2 and NFU1 in the Maturation of Human Mitochondrial Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166924.

- Broderick, J.B.; Duffus, B.R.; Duschene, K.S.; Shepard, E.M. Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4229–4317.

- Dowling, D.P.; Vey, J.L.; Croft, A.K.; Drennan, C.L. Structural Diversity in the AdoMet Radical Enzyme Superfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Proteins Proteom. 2012, 1824, 1178–1195.

- Cicchillo, R.M.; Iwig, D.F.; Jones, A.D.; Nesbitt, N.M.; Baleanu-Gogonea, C.; Souder, M.G.; Tu, L.; Booker, S.J. Lipoyl Synthase Requires Two Equivalents of S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine to Synthesize One Equivalent of Lipoic Acid. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6378–6386.

- Lanz, N.D.; Booker, S.J. Identification and Function of Auxiliary Iron-Sulfur Clusters in Radical SAM Enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1824, 1196–1212.

- Fontecave, M.; Ollagnier-de-Choudens, S.; Mulliez, E. Biological Radical Sulfur Insertion Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2149–2166.

- Camponeschi, F.; Muzzioli, R.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Piccioli, M.; Banci, L. Paramagnetic 1H NMR Spectroscopy to Investigate the Catalytic Mechanism of Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 4514–4522.

- Hendricks, A.L.; Wachnowsky, C.; Fries, B.; Fidai, I.; Cowan, J.A. Characterization and Reconstitution of Human Lipoyl Synthase (LIAS) Supports ISCA2 and ISCU as Primary Cluster Donors and an Ordered Mechanism of Cluster Assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1598.

- Lanz, N.D.; Rectenwald, J.M.; Wang, B.; Kakar, E.S.; Laremore, T.N.; Booker, S.J.; Silakov, A. Characterization of a Radical Intermediate in Lipoyl Cofactor Biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13216–13219.

- McLaughlin, M.I.; Lanz, N.D.; Goldman, P.J.; Lee, K.-H.; Booker, S.J.; Drennan, C.L. Crystallographic Snapshots of Sulfur Insertion by Lipoyl Synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9446–9450.

- Cameron, J.M.; Janer, A.; Levandovskiy, V.; Mackay, N.; Rouault, T.A.; Tong, W.-H.; Ogilvie, I.; Shoubridge, E.A.; Robinson, B.H. Mutations in Iron-Sulfur Cluster Scaffold Genes NFU1 and BOLA3 Cause a Fatal Deficiency of Multiple Respiratory Chain and 2-Oxoacid Dehydrogenase Enzymes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 486–495.

- Nasta, V.; Suraci, D.; Gourdoupis, S.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. A Pathway for Assembling 2+ Clusters in Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Protein Biogenesis. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 2312–2327.

- Nasta, V.; Giachetti, A.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Banci, L. Structural Insights into the Molecular Function of Human BOLA1-GRX5 and BOLA3-GRX5 Complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1861, 2119–2131.

- Uzarska, M.A.; Nasta, V.; Weiler, B.D.; Spantgar, F.; Ciofi-Baffoni, S.; Saviello, M.R.; Gonnelli, L.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Banci, L.; Lill, R. Mitochondrial Bol1 and Bol3 Function as Assembly Factors for Specific Iron-Sulfur Proteins. Elife 2016, 5, e16673.

- Maio, N.; Rouault, T.A. Outlining the Complex Pathway of Mammalian Fe-S Cluster Biogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 411–426.

- Maio, N.; Rouault, T.A. Mammalian Iron Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis and Human Diseases. IUBMB Life 2022, 74, 705–714.

- Wachnowsky, C.; Fidai, I.; Cowan, J.A. Iron–Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis and Trafficking—Impact on Human Disease Conditions. Metallomics 2018, 10, 9–29.

- Baker, P.R.; Friederich, M.W.; Swanson, M.A.; Shaikh, T.; Bhattacharya, K.; Scharer, G.H.; Aicher, J.; Creadon-Swindell, G.; Geiger, E.; MacLean, K.N.; et al. Variant Non Ketotic Hyperglycinemia Is Caused by Mutations in LIAS, BOLA3 and the Novel Gene GLRX5. Brain 2014, 137, 366–379.

- Liu, G.; Guo, S.; Anderson, G.J.; Camaschella, C.; Han, B.; Nie, G. Heterozygous Missense Mutations in the GLRX5 Gene Cause Sideroblastic Anemia in a Chinese Patient. Blood 2014, 124, 2750–2751.

- Daher, R.; Mansouri, A.; Martelli, A.; Bayart, S.; Manceau, H.; Callebaut, I.; Moulouel, B.; Gouya, L.; Puy, H.; Kannengiesser, C.; et al. GLRX5 Mutations Impair Heme Biosynthetic Enzymes ALA Synthase 2 and Ferrochelatase in Human Congenital Sideroblastic Anemia. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 128, 342–351.

- Navarro-Sastre, A.; Tort, F.; Stehling, O.; Uzarska, M.A.; Arranz, J.A.; Del Toro, M.; Labayru, M.T.; Landa, J.; Font, A.; Garcia-Villoria, J.; et al. A Fatal Mitochondrial Disease Is Associated with Defective NFU1 Function in the Maturation of a Subset of Mitochondrial Fe-S Proteins. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 656–667.

- Stéphanie, P.; Catherine, B.; Thierry, S.; Jean-Luc, V.; Isabelle, L.; Sara, S.; Christophe, V.; Marie-Cécile, N. “Idiopathic” Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Early Infancy: Excluding NFU1 Deficiency. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2019, 12, 325–328.

- Uzunhan, T.A.; Çakar, N.E.; Seyhan, S.; Aydin, K. A Genetic Mimic of Cerebral Palsy: Homozygous NFU1 Mutation with Marked Intrafamilial Phenotypic Variation. Brain Dev. 2020, 42, 756–761.

- Lebigot, E.; Gaignard, P.; Dorboz, I.; Slama, A.; Rio, M.; de Lonlay, P.; Héron, B.; Sabourdy, F.; Boespflug-Tanguy, O.; Cardoso, A.; et al. Impact of Mutations within the Cluster or the Lipoic Acid Biosynthesis Pathways on Mitochondrial Protein Expression Profiles in Fibroblasts from Patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 122, 85–94.

- de Souza, P.V.S.; Bortholin, T.; Burlin, S.; Naylor, F.G.M.; de Rezende Pinto, W.B.V.; Oliveira, A.S.B. NFU1 -Related Disorders as Key Differential Diagnosis of Cavitating Leukoencephalopathy. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2018, 7, 40–42.

- Birjiniuk, A.; Glinton, K.E.; Villafranco, N.; Boyer, S.; Laufman, J.; Mizerik, E.; Scott, D.; Elsea, S.H.; Galambos, C.; Varghese, N.P.; et al. Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome 1: An Unusual Cause of Developmental Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2020, 182, 755–761.

- Nizon, M.; Boutron, A.; Boddaert, N.; Slama, A.; Delpech, H.; Sardet, C.; Brassier, A.; Habarou, F.; Delahodde, A.; Correia, I.; et al. Leukoencephalopathy with Cysts and Hyperglycinemia May Result from NFU1 Deficiency. Mitochondrion 2014, 15, 59–64.

- Invernizzi, F.; Ardissone, A.; Lamantea, E.; Garavaglia, B.; Zeviani, M.; Farina, L.; Ghezzi, D.; Moroni, I. Cavitating Leukoencephalopathy with Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunction Syndrome and NFU1 Mutations. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 412.

- Ahting, U.; Mayr, J.A.; Vanlander, A.V.; Hardy, S.A.; Santra, S.; Makowski, C.; Alston, C.L.; Zimmermann, F.A.; Abela, L.; Plecko, B.; et al. Clinical, Biochemical, and Genetic Spectrum of Seven Patients with NFU1 Deficiency. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 123.

- Ames, E.G.; Neville, K.L.; McNamara, N.A.; Keegan, C.E.; Elsea, S.H. Clinical Reasoning: A 12-Month-Old Child with Hypotonia and Developmental Delays. Neurology 2020, 95, 184–187.

- Jin, D.; Yu, T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.-A. Novel NFU1 Variants Induced MMDS Behaved as Special Leukodystrophy in Chinese Sufferers. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 62, 255–261.

- Haack, T.B.; Rolinski, B.; Haberberger, B.; Zimmermann, F.; Schum, J.; Strecker, V.; Graf, E.; Athing, U.; Hoppen, T.; Wittig, I.; et al. Homozygous Missense Mutation in BOLA3 Causes Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome in Two Siblings. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013, 36, 55–62.

- Nikam, R.M.; Gripp, K.W.; Choudhary, A.K.; Kandula, V. Imaging Phenotype of Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunction Syndrome 2, a Rare BOLA3-Associated Leukodystrophy. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2018, 176, 2787–2790.

- Kohda, M.; Tokuzawa, Y.; Kishita, Y.; Nyuzuki, H.; Moriyama, Y.; Mizuno, Y.; Hirata, T.; Yatsuka, Y.; Yamashita-Sugahara, Y.; Nakachi, Y.; et al. A Comprehensive Genomic Analysis Reveals the Genetic Landscape of Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complex Deficiencies. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005679.

- Nishioka, M.; Inaba, Y.; Motobayashi, M.; Hara, Y.; Numata, R.; Amano, Y.; Shingu, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Murayama, K.; Ohtake, A.; et al. An Infant Case of Diffuse Cerebrospinal Lesions and Cardiomyopathy Caused by a BOLA3 Mutation. Brain Dev. 2018, 40, 484–488.

- Imai-Okazaki, A.; Kishita, Y.; Kohda, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Fushimi, T.; Matsunaga, A.; Yatsuka, Y.; Hirata, T.; Harashima, H.; Takeda, A.; et al. Cardiomyopathy in Children with Mitochondrial Disease: Prognosis and Genetic Background. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 279, 115–121.

- Bindu, P.S.; Sonam, K.; Chiplunkar, S.; Govindaraj, P.; Nagappa, M.; Vekhande, C.C.; Aravinda, H.R.; Ponmalar, J.J.; Mahadevan, A.; Gayathri, N.; et al. Mitochondrial Leukoencephalopathies: A Border Zone between Acquired and Inherited White Matter Disorders in Children? Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 20, 84–92.

- Stutterd, C.A.; Lake, N.J.; Peters, H.; Lockhart, P.J.; Taft, R.J.; van der Knaap, M.S.; Vanderver, A.; Thorburn, D.R.; Simons, C.; Leventer, R.J. Severe Leukoencephalopathy with Clinical Recovery Caused by Recessive BOLA3 Mutations. JIMD Rep. 2018, 43, 63–70.

- Torraco, A.; Ardissone, A.; Invernizzi, F.; Rizza, T.; Fiermonte, G.; Niceta, M.; Zanetti, N.; Martinelli, D.; Vozza, A.; Verrigni, D.; et al. Novel Mutations in IBA57 Are Associated with Leukodystrophy and Variable Clinical Phenotypes. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 102–111.

- Ajit Bolar, N.; Vanlander, A.V.; Wilbrecht, C.; Van der Aa, N.; Smet, J.; De Paepe, B.; Vandeweyer, G.; Kooy, F.; Eyskens, F.; De Latter, E.; et al. Mutation of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Gene IBA57 Causes Severe Myopathy and Encephalopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 2590–2602.

- Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Y. Phenotypic Spectrum of Mutations in IBA57, a Candidate Gene for Cavitating Leukoencephalopathy. Clin. Genet. 2018, 93, 235–241.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Kong, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Y. Genotypic Spectrum and Natural History of Cavitating Leukoencephalopathies in Childhood. Pediatr. Neurol. 2019, 94, 38–47.

- Hamanaka, K.; Miyatake, S.; Zerem, A.; Lev, D.; Blumkin, L.; Yokochi, K.; Fujita, A.; Imagawa, E.; Iwama, K.; Nakashima, M.; et al. Expanding the Phenotype of IBA57 Mutations: Related Leukodystrophy Can Remain Asymptomatic. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 63, 1223–1229.

- Ishiyama, A.; Sakai, C.; Matsushima, Y.; Noguchi, S.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Endo, Y.; Hayashi, Y.K.; Saito, Y.; Nakagawa, E.; Komaki, H.; et al. IBA57 Mutations Abrogate Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Leading to Cavitating Leukoencephalopathy. Neurol. Genet. 2017, 3, e184.

- Debray, F.-G.; Stümpfig, C.; Vanlander, A.V.; Dideberg, V.; Josse, C.; Caberg, J.-H.; Boemer, F.; Bours, V.; Stevens, R.; Seneca, S.; et al. Mutation of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Gene IBA57 Causes Fatal Infantile Leukodystrophy. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2015, 38, 1147–1153.

- Zhan, F.; Liu, X.; Ni, R.; Liu, T.; Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Tian, W.; Luan, X.; Cao, L. Novel IBA57 Mutations in Two Chinese Patients and Literature Review of Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunction Syndrome. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 311–317.

- Al-Hassnan, Z.N.; Al-Dosary, M.; Alfadhel, M.; Faqeih, E.A.; Alsagob, M.; Kenana, R.; Almass, R.; Al-Harazi, O.S.; Al-Hindi, H.; Malibari, O.I.; et al. ISCA2 Mutation Causes Infantile Neurodegenerative Mitochondrial Disorder. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 52, 186–194.

- Alaimo, J.T.; Besse, A.; Alston, C.L.; Pang, K.; Appadurai, V.; Samanta, M.; Smpokou, P.; McFarland, R.; Taylor, R.W.; Bonnen, P.E. Loss-of-function Mutations in ISCA2 Disrupt 4Fe–4S Cluster Machinery and Cause a Fatal Leukodystrophy with Hyperglycinemia and MtDNA Depletion. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 537–549.

- Alfadhel, M.; Nashabat, M.; Alrifai, M.T.; Alshaalan, H.; Al Mutairi, F.; Al-Shahrani, S.A.; Plecko, B.; Almass, R.; Alsagob, M.; Almutairi, F.B.; et al. Further Delineation of the Phenotypic Spectrum of ISCA2 Defect: A Report of Ten New Cases. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2018, 22, 46–55.

- Eidi, M.; Garshasbi, M. A Novel ISCA2 Variant Responsible for an Early-Onset Neurodegenerative Mitochondrial Disorder: A Case Report of Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome 4. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 153.

- Hartman, T.G.; Yosovich, K.; Michaeli, H.G.; Blumkin, L.; Ben-Sira, L.; Lev, D.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Zerem, A. Expanding the Genotype-Phenotype Spectrum of ISCA2-Related Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunction Syndrome-Cavitating Leukoencephalopathy and Prolonged Survival. Neurogenetics 2020, 21, 243–249.

- Toldo, I.; Nosadini, M.; Boscardin, C.; Talenti, G.; Manara, R.; Lamantea, E.; Legati, A.; Ghezzi, D.; Perilongo, G.; Sartori, S. Neonatal Mitochondrial Leukoencephalopathy with Brain and Spinal Involvement and High Lactate: Expanding the Phenotype of ISCA2 Gene Mutations. Metab. Brain Dis. 2018, 33, 805–812.

- Shukla, A.; Hebbar, M.; Srivastava, A.; Kadavigere, R.; Upadhyai, P.; Kanthi, A.; Brandau, O.; Bielas, S.; Girisha, K.M. Homozygous p.(Glu87Lys) Variant in ISCA1 Is Associated with a Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 62, 723–727.

- Shukla, A.; Kaur, P.; Girisha, K.M. Report of the Third Family with Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome 5 Caused by the Founder Variant p.(Glu87Lys) in ISCA1. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2018, 7, 130–133.

- Torraco, A.; Stehling, O.; Stümpfig, C.; Rösser, R.; De Rasmo, D.; Fiermonte, G.; Verrigni, D.; Rizza, T.; Vozza, A.; Di Nottia, M.; et al. ISCA1 Mutation in a Patient with Infantile-Onset Leukodystrophy Causes Defects in Mitochondrial Proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2739–2754.

- Lebigot, E.; Hully, M.; Amazit, L.; Gaignard, P.; Michel, T.; Rio, M.; Lombès, M.; Thérond, P.; Boutron, A.; Golinelli-Cohen, M.P. Expanding the Phenotype of Mitochondrial Disease: Novel Pathogenic Variant in ISCA1 Leading to Instability of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster in the Protein. Mitochondrion 2020, 52, 75–82.

- Kevelam, S.H.; Rodenburg, R.J.; Wolf, N.I.; Ferreira, P.; Lunsing, R.J.; Nijtmans, L.G.; Mitchell, A.; Arroyo, H.A.; Rating, D.; Vanderver, A.; et al. NUBPL Mutations in Patients with Complex I Deficiency and a Distinct MRI Pattern. Neurology 2013, 80, 1577–1583.

- Calvo, S.E.; Tucker, E.J.; Compton, A.G.; Kirby, D.M.; Crawford, G.; Burtt, N.P.; Rivas, M.; Guiducci, C.; Bruno, D.L.; Goldberger, O.A.; et al. High-Throughput, Pooled Sequencing Identifies Mutations in NUBPL and FOXRED1 in Human Complex I Deficiency. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 851–858.

- Tucker, E.J.; Mimaki, M.; Compton, A.G.; McKenzie, M.; Ryan, M.T.; Thorburn, D.R. Next-Generation Sequencing in Molecular Diagnosis: NUBPL Mutations Highlight the Challenges of Variant Detection and Interpretation. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 411–418.

- Kimonis, V.; Al Dubaisi, R.; Maclean, A.E.; Hall, K.; Weiss, L.; Stover, A.E.; Schwartz, P.H.; Berg, B.; Cheng, C.; Parikh, S.; et al. NUBPL Mitochondrial Disease: New Patients and Review of the Genetic and Clinical Spectrum. J. Med. Genet. 2021, 58, 314–325.

- Spiegel, R.; Saada, A.; Halvardson, J.; Soiferman, D.; Shaag, A.; Edvardson, S.; Horovitz, Y.; Khayat, M.; Shalev, S.A.; Feuk, L.; et al. Deleterious Mutation in FDX1L Gene Is Associated with a Novel Mitochondrial Muscle Myopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 22, 902–906.

- Gurgel-Giannetti, J.; Lynch, D.S.; De Paiva, A.R.B.; Lucato, L.; Yamamoto, G.; Thomsen, C.; Basu, S.; Freua, F.; Giannetti, A.V.; Assis, B.D.R.D.; et al. A Novel Complex Neurological Phenotype Due to a Homozygous Mutation in FDX2. Brain 2018, 141, 2289–2298.

- Johansson, C.; Roos, A.K.; Montano, S.J.; Sengupta, R.; Filippakopoulos, P.; Guo, K.; von Delft, F.; Holmgren, A.; Oppermann, U.; Kavanagh, K.L. The Crystal Structure of Human GLRX5: Iron-Sulfur Cluster Co-Ordination, Tetrameric Assembly and Monomer Activity. Biochem. J. 2011, 433, 303–311.

- Cai, K.; Liu, G.; Frederick, R.O.; Xiao, R.; Montelione, G.T.; Markley, J.L. Structural/Functional Properties of Human NFU1, an Intermediate Carrier in Human Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis. Structure 2016, 24, 2080–2091.

- Wachnowsky, C.; Wesley, N.A.; Fidai, I.; Cowan, J.A. Understanding the Molecular Basis of Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome 1 (MMDS1)-Impact of a Disease-Causing Gly208Cys Substitution on Structure and Activity of NFU1 in the Fe/S Cluster Biosynthetic Pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 790–807.

- Tonduti, D.; Dorboz, I.; Imbard, A.; Slama, A.; Boutron, A.; Pichard, S.; Elmaleh, M.; Vallée, L.; Benoist, J.F.; Ogier, H.; et al. New Spastic Paraplegia Phenotype Associated to Mutation of NFU1. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 13.

- Wesley, N.A.; Wachnowsky, C.; Fidai, I.; Cowan, J.A. Understanding the Molecular Basis for Multiple Mitochondrial Dysfunctions Syndrome 1 (MMDS1): Impact of a Disease-Causing Gly189Arg Substitution on NFU1. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 3838–3848.

- Tong, W.-H.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Huynh, B.H.; Rouault, T.A. Subcellular Compartmentalization of Human Nfu, an Iron-Sulfur Cluster Scaffold Protein, and Its Ability to Assemble a Cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 9762–9767.